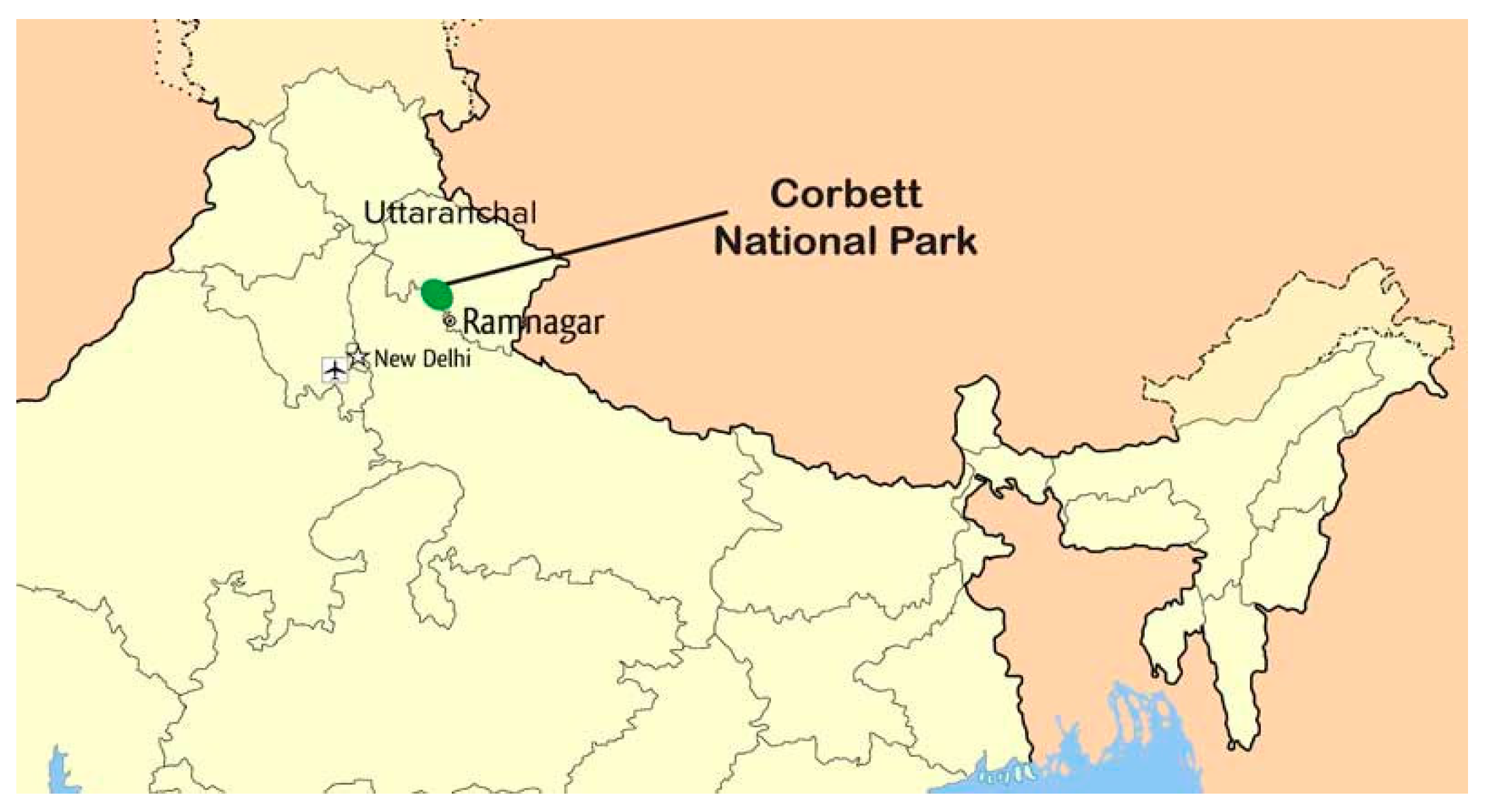

Investigating Environmental Transgressions at Corbett Tiger Reserve, India

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review of Literature

2.1. Deviant Tourist Behaviors

2.2. Place Attachment

2.3. Sustainable Practices in Tourism

3. Materials and Methods

- What is the stakeholders’ opinion regarding nature tourism at CTR?

- What are the attitudes/behaviors toward and the experience of CTR?

- How can environmental transgressions be confronted in and around CTR?

- What types of tourism development strategies are being followed around CTR?

4. Results

4.1. Turmoil in Tourism Development

4.2. Tourists’ Attitudes toward CTR

4.3. Tourists’ Behaviors toward CTR

4.4. Environmental Transgressions

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prakash, O. Wildlife destruction: A legacy of the colonial state in India. In Proceedings of the Indian History Congress; Indian History Congress: Pune, India, 2006; Volume 67, pp. 692–702. [Google Scholar]

- Guha, R. Radical American Environmentalism and Wilderness Preservation: A Third World Critique. In Varieties of Environmentalism; Guha, R., Martinez-Alier, J., Eds.; Essays North and South: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Karanth, K.; DeFries, R. Nature-based tourism in Indian protected areas: New challenges for park management. Conserv. Lett. 2011, 4, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, C.P.; DeCoursey, M. The Annapurna Conservation Area Project: A Pioneering Example of Sustainable Tourism. In Cater Ecotourism: A Sustainable Option? John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Johannesen, A.B.; Skonhoft, A. Tourism, poaching and wildlife conservation: What can integrated conservation and development projects accomplish? Resour. Energy Econ. 2005, 27, 208–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Higginbottom, K.; Green, R.; Northrope, C. A framework for managing the negative impacts of wildlife tourism on wildlife. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2003, 8, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A. Is wildlife tourism benefiting Indian protected areas? A survey. Curr. Issues Tour. 2012, 15, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Caprara, G.V.; Zsolnai, L. Corporate transgressions through moral disengagement. J. Hum. Values 2000, 6, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, A.M.; Hess, S.; Alonso, I.; Frías-Armenta, M. Do lay people classify environmental transgressions in the same way as public administrations? Psyecology 2011, 2, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, J.N.; Gavin, M.C.; Gore, M.L. Detecting and understanding non-compliance with conservation rules. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 189, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.J.; Ham, S.H.; Hughes, M. Picking up litter: An application of theory-based communication to influence tourist behavior in protected areas. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 879–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannam, K.; Diekmann, A. Tourism and India: A Critical Introduction; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; p. 75. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, S. India Has Two Weeks to Solve the Tiger vs Tourism Dilemma. Available online: https://www.thenational.ae/world/asia/india-has-two-weeks-to-solve-the-tiger-vs-tourism-dilemma-1.403634 (accessed on 10 July 2017).

- Sharpley, R. Rural tourism and the challenge of tourism diversification: The case of Cyprus. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R. The Politics of Ecotourism and the Developing World. J. Ecotour. 2006, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, B.; Martín, A.M.; Ruiz, C.; Hidalgo, M.C. The role of place identity and place attachment in breaking environmental protection laws. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semeniuk, C.A.; Haider, W.; Cooper, A.; Rothley, K.D. A linked model of animal ecology and human behavior for the management of wildlife tourism. Ecol. Model. 2010, 221, 2699–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, C.M.; Hill, W. Impacts of recreation and tourism on plant diversity and vegetation in protected areas in Australia. J. Environ. Manag. 2007, 85, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geneletti, D.; Van Duren, I. Protected area zoning for conservation and use: A combination of spatial multicriteria and multi-objective evaluation. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 85, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandiar, K.; Dowling, R.; Pearce, J. Pro-environmental behaviour in national parks: Smart for one, but dump for all. In CAUTHE 2018: Get Smart: Paradoxes and Possibilities in Tourism, Hospitality and Events Education and Research; Young, T., Stolk, P., McGinnis, G., Eds.; Newcastle Business School, The University of Newcastle: Newcastle, Australia, 2018; pp. 741–744. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; Yu, P.; Chu, G. What influences tourists’ intention to participate in the Zero Litter Initiative in mountainous tourism areas: A case study of Huangshan National Park, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 657, 1127–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, C.P.; Hendee, J.C.; Schuster, R.M. Wilderness visitor management: Stewardship for Quality Experiences. In Wilderness Management: Stewardship and Protection of Resources and Values, 4th ed.; Fulcrum Publishing: Golden, CO, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, W.; Laing, J.; Beeton, S. The Future of Nature-Based Tourism in the Asia-Pacific Region. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, D.I.; Stricker, H.K.; Hagenloh, G. Outcome-focused national park experience management: Transforming participants, promoting social well-being, and fostering place attachment. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 358–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budruk, M.; Thomas, H.; Tyrrell, T. Urban green spaces: A study of place attachment and environmental attitudes in India. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2009, 22, 824–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coghlan, A.; Castley, G. A matter of perspective: Residents’, regulars’ and locals’ perceptions of private tourism eco-lodge concessions in Kruger National Park, South Africa. Curr. Issues Tour. 2013, 16, 682–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpenny, E.A. Pro-environmental behaviors and park visitors: The effect of place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, G.; Graefe, A.; Manning, R.; Bacon, J. An examination of the relationships between leisure activity involvement and place attachment among hikers along the Appalachian Trail. J. Leis. Res. 2003, 35, 249–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.; Vaske, J. The measurement of place attachment: Validity and generalizability of a psychometric approach. For. Sci. 2003, 49, 830–840. [Google Scholar]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Weiler, B.; Smith, L. Place attachment and pro-environmental behavior in national parks: The development of a conceptual framework. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelenski, J.; Dopko, R.; Capaldi, C. Cooperation is in our nature: Nature exposure may promote cooperative and environmentally sustainable behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seamon, D. Place attachment and phenomenology: The synergistic dynamism of place. In Place Attachment: Advances in Theory, Methods, and Applications; Manzo, L.C., Devine-Wright, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo, M.C.; Hernandez, B. Regular Article: Place Attachment: Conceptual and Empirical Questions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serenari, C.; Leung, Y.; Attarian, A.; Franck, C. Understanding environmentally significant behavior among whitewater rafting and trekking guides in the Garhwal Himalaya, India. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 757–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payton, M.; Fulton, D.; Anderson, D. Influence of place attachment and trust on civic action: A study at Sherburne National Wildlife Refuge. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2007, 18, 511–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, P. Towards a developmental theory of place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.; Andreas, N. Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behavior: A review. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.T. How recreation involvement, place attachment and conservation commitment affect environmentally responsible behavior. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 895–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toudert, D.; Bringas-Rabago, N. Exploring the impact of destination attachment on the intentional behavior of the US visitors familiarized with Baja California, Mexico. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 21, 805–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buta, N.; Holland, S.M.; Kaplanidou, K. Local communities and protected areas: The mediating role of place attachment for pro-environmental civic engagement. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2014, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.L.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, S. Predicting residents’ pro-environmental behaviors at tourist sites: The role of awareness of disaster’s consequences, values, and place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. Destination development dilemma—Case of Manali in Himachal Himalaya. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 1152–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briassoulis, H. Sustainable tourism and the question of the commons. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 1065–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, V.T.; Hawkins, R. Sustainable Tourism: A Marketing Perspective; Routledge: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, C. Sustainable tourism as an adaptive paradigm. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 850–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarinen, J. Traditions of sustainability in tourism studies. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 1121–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branwell, B.; Lane, B. Sustainable tourism: An evolving global. J. Sustain. Tour. 1993, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walpole, M.J.; Goodwin, H.J. Local economic impacts of dragon tourism in Indonesia. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 559–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, J.; Sinclair, J.; Berkes, F.; Singh, R.B. Accelerated tourism development and its impacts in Kullu-Manali, HP, India. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2002, 27, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kuniyal, J.C. Solid waste management in the Himalayan trails and expedition summits. J. Sustain. Tour. 2005, 13, 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, A.; Hickey, G.M.; Badola, R.; Hussain, S.A. Understanding the local socio-political processes affecting conservation management outcomes in Corbett Tiger Reserve, India. Environ. Manag. 2014, 53, 913–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, L.C.; Jayawardena, C.; Clayton, A. Sustainable tourism development in the Caribbean: Practical challenges. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2003, 15, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telfer, D.; Sharpley, R. Tourism and Development in the Developing World; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jhala, Y.V.; Gopal, R.; Qureshi, Q. (Eds.) The Status of Tigers, Co-Predators and Prey in INDIA 2014; National Tiger Conservation Authority: New Delhi, India; Wildlife Institute of India: Dehradun, India, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Badola, R.; Hussain, S.A.; Mishra, B.K.; Konthoujam, B.; Thapliyal, S.; Dhakate, P.M. An assessment of ecosystem services of Corbett Tiger Reserve, India. Environmentalist 2010, 30, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, A.; Badola, R.; Hussain, S.A.; Hickey, G.M. Assessing the utility of stakeholder analysis to protected areas management: The case of Corbett National Park, India. Biol. Conserv. 2010, 143, 2956–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusain, R. Tourist Numbers at All-Time High in Corbett Park. Daily Mail. Available online: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/indiahome/indianews/article-3065580/Corbett-National-Park-Tourist-numbers-time-high-Corbett-park.html (accessed on 10 August 2017).

- Sautter, E.T.; Leisen, B. Managing stakeholders a tourism planning model. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, H.R. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013; p. 175. [Google Scholar]

- Boddy, C.R. Sample size for qualitative research. Qual. Mark. Res. 2005, 19, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Traditions; SAGE: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, M.A. The richness of phenomenology: Philosophic, theoretic and methodologic concerns. In Critical Issues in Qualitative Research Methods; Morse, J.M., Ed.; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 117–133. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S.B. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation; John Wiley & Sons: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S. The role of the judiciary in promoting sustainable development: Need for specialized environment court in India. J. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 4, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kajan, E. Community perceptions to place attachment and tourism development in Finnish Lapland. Tour. Geogr. 2014, 16, 490–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marion, J.; Reid, S. Minimizing visitor impacts to protected areas: The efficacy of low impact education programs. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, R.; Packer, J.; Hughes, K. Tourists’ support for conservation messages and sustainable management practices in wildlife tourism experiences. Tour. Manag. 2009, 3, 658–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Place attachment enhances psychological need satisfaction. Environ. Behav. 2017, 49, 359–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callicot, J.B.; Ames, R.T. Nature in Asian Traditions of Thought: Essays in Environmental Philosophy; SUNY Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, G.L.; Howard, P. When wildlife tourism goes wrong: A case study of stakeholder and management issues regarding Dingoes on Fraser Island, Australia. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C. Limits to community participation in the tourism development process in developing countries. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 613–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeppel, H. Collaborative governance for low-carbon tourism: Climate change initiatives by Australian tourism agencies. Curr. Issues Tour. 2011, 15, 603–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, R.; Fennell, D.A. Managing protected areas for sustainable tourism: Prospects for adaptive co-management. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, B.C.; Qureshi, Q.; Uniyal, V.K.; Sen, S. Economics of wildlife tourism—Contribution to livelihoods of communities around Kanha Tiger Reserve, India. J. Ecotour. 2012, 11, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sharma, T.; Chen, J.S.; Liu, W.-Y. Investigating Environmental Transgressions at Corbett Tiger Reserve, India. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5766. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205766

Sharma T, Chen JS, Liu W-Y. Investigating Environmental Transgressions at Corbett Tiger Reserve, India. Sustainability. 2019; 11(20):5766. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205766

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharma, Tanmay, Joseph S. Chen, and Wan-Yu Liu. 2019. "Investigating Environmental Transgressions at Corbett Tiger Reserve, India" Sustainability 11, no. 20: 5766. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205766

APA StyleSharma, T., Chen, J. S., & Liu, W.-Y. (2019). Investigating Environmental Transgressions at Corbett Tiger Reserve, India. Sustainability, 11(20), 5766. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205766