1. Introduction: Scaling Up Sustainable Business and Finance

We are facing unprecedented sustainability challenges. Four out of nine critical limits of Earth-system processes have been transgressed due to human activity. These ‘planetary boundaries’ represent humanity’s ‘safe operating space’, whose breach increases the risk of unacceptable global environmental change [

1,

2]. In order to safeguard Earth’s life-support system on which the welfare of current and future generations depends, changes in the economic realm are necessary [

3]. However, to ensure sustainable development, there is not only a need to re-think how the economic playing field is structured, but also the regulatory system that governs it. Business and financial market law reforms are increasingly seen as key for scaling up sustainability [

4]. The European Union (EU) has a particular opportunity to engage in the transition due to the capacity and resources the region commands. The EU is one of the world’s biggest markets and has the power to shape progress towards a sustainable development regime.

If we want to move from sustainability rhetoric to sustainability action, sustainability needs to become a guiding strategy for the desired future [

5]. The potential of such a strategy is often framed as either weak or strong sustainability (e.g., References [

6,

7]). The ‘desired future’ is here conceptualised as the ‘safe operating space’ for global societal development [

1,

2]. Hence, strong sustainability requires the appreciation of the complex relationships and connections between the parts of a system and the function of the whole [

8] or, in other words, the use of systems thinking. Strong sustainability is furthermore considered to be seriously limited by environmental characteristics such as irreversibility, uncertainty and the existence of ‘critical’ components of natural capital [

9,

10]. Therefore, to achieve strong sustainability, we need to stay within planetary boundaries. However, it needs to be noted that the multidimensional issues related to the ‘social foundation’ presented as the ‘doughnut’—a combination of the planetary boundaries concept and social boundaries—is the preferred framework defining the sustainability challenge as it includes the social dimension of sustainability (see Reference [

11]).

A dominant perception is that welfare is not dependent on a specific form of capital, which is informing weak sustainability measures [

9,

10]. This means that the critical limits of the planet are not acknowledged. This perception often results in a business-as-usual action agenda with market-oriented approaches including reporting and transparency practices rather than mandatory legislation and regulation [

12]. This action agenda informs most traditional policy approaches [

13].

There has been limited progress so far in integrating sustainable development in EU business and financial market law [

4]. Article 11 in the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) codifies the core part of the principle of sustainable development and is a legally binding rule in EU law (see also References [

14,

15,

16]). This rule means that a cross-sectoral integration of the principle should feed into all areas of EU law and policy with the aim of achieving sustainable development [

17]. There have been some recent improvements, such as the ‘sustainable finance initiative’ and the launch of the Action Plan ‘Financing Sustainable Growth’ [

18].

Despite this recent progress, a continuous problem is the EU’s tendency to compartmentalize, with each Directorate General (DG) of the European Commission (EC) and each sector discussing their own traditional issues. This has also contributed to company law being ignored in sustainability debates [

13]. Another contributing factor is the dominant norm related to the purpose of the corporation, namely, to maximise returns to shareholders. This norm is related to the notion of viewing the corporation as the shareholders’ property, or as a ‘nexus of contracts’ in which the shareholders need to receive the main protection, a norm that does not seem to follow from company law [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. The narrow focus on what the purpose of the corporation is, limits the possibility to change corporate behaviour and there is therefore a need to include regulation and governance of business decision-making in the toolbox for sustainability [

22]. It is not something that prevails over all economic activity, but it is an important aspect to consider for enabling sustainable corporate behaviour.

One implication coming from institutional fragmentation and the usage of the shareholder maximisation norm seems to be a research gap, with very limited systematical analysis of EU business law and financial market law in relation to sustainability [

22]. The paper aims to address this gap by first interrogating these two fields of law through a sustainability lens, using the ‘safe operating space’ for global societal development [

1,

2] as an entry point for the analysis of where we can find content in line with or related to the sustainable development principle. In doing this, it analyses EU business and financial market law in conjunction, as there are many related fields of regulation such as accounting regulation that both link together these fields of law and has been target for intervention to facilitate sustainable market action (e.g., the adoption of the Non-Financial Reporting Directive). Finally, it links these fields of law to sustainability-related EU policies and legal commitments. The reason is that it is important to see what impact other fields of law and policy that

do integrate the sustainable development principle have on business and financial market law, considering the lack of progress to date. For the scope of this paper, I, therefore, use the term business law as a broad concept, which includes company law, accounting law and soft law instruments (see also Reference [

24]). This approach facilitates an analytical process of assessing business law’s interrelations with financial market law and the limited progress of integrating the sustainable development principle.

The approach of including soft law instruments is particularly useful when focusing on the latter since the interpretation of policy processes has an important role to play when there is such little progress to date in regards the integration of this principle. The EU political cycle and the interrelated policy-making process is both complex and time-consuming and in which political commitment for different policy areas becomes crucial. This means that it is useful to appreciate law-making as a process spanning from ‘soft informal agreements through intermediate blends of obligation, precision, and delegation to hard legal arrangements’ [

25] (p. 454). An important component of this view of soft law is how different actors beyond lawmakers shape what is practiced, in this case business and finance. This is however beyond the scope of this study.

When viewing the law as a process within this continuum it is useful to use a learning-based theoretical approach for governance analysis. This learning-based approach includes incorporating a specific notion of how actors shape collective action in society and therefore affecting the governance outcome. However, the way actors present themselves in order to advance certain interests does not occur ‘automatically’ or ‘spontaneously’. It needs to be organised. Specific conditions need to be in place for the possibility of success of the choice of norm that the actor represents. This condition reflects the need to organise reflexivity—actors’ return over their pre-existing frames (see the work of Schön and Argyris on theories of action, double-loop learning and organisational learning e.g., Reference [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]). I, therefore, deploy a reflexive understanding of governance, which refers to ‘the problem of shaping societal development in the light of the reflexivity of steering strategies’ [

31] (p. 4, see also Reference [

32]). More specifically, I refer to the concept of

genetic reflexive governance, whereby an actor’s relationship with the past outline the actor’s

reflectibility and the actor’s relationship with the future outline its

destinability. An actor’s reflectibility is the process in which it reconstructs its identity based on its past actions, adjusted to a changed context. It also means that the actors create a relation to the ‘collective identity making’. In other words, an actor has the possibility to represent itself as a collective actor in action. Finally, this representation can be described as the operation of self-capacitation that is ‘reflected’ in the actor’s image. Furthermore, the construction of an actor’s ‘self-capacitation’ is related to the notion of ‘ability-to-do’. This means the actor’s notion of what it is able to do in a new context, whereas it is possible to ensure its own ‘collective identity making’. Here certain conditions and constraints become important for the actor’s ability to act. In addition, the future contexts also affect the actor’s self-capacitation, constructing its capacity to form an identity as well as its destiny—the actor’s destinability [

33]. By relating and establishing links between different policy domains and by addressing institutional- and actor-learning processes, it is possible to identify certain blind spots in each domain. Particularly interesting for this study of EU business and financial market law is that such an approach can better respond to concerns about the democratic deficit and to the fulfilment of the public interest than the currently dominant neo-institutionalist approaches can [

30]. These are some of the main proposed benefits of genetic reflexive governance.

In the context of past and future decision-making processes related to EU business and finance, it is important to address the implications around the financialisation of our economy. Corporate financialisation refers to ‘the increasing dominance of financial actors, markets, practices, measurements and narratives at various scales, resulting in a structural transformation of economies, firms (including financial institutions), states and households’ [

34]. In other words; profit-making increasingly occurs through financial channels rather than through non-financial strategies in the real economy such as trade and commodity production (e.g., Reference [

35]). However, it needs to be noted that financialization is not always the same everywhere.

The growth of finance has naturally benefited actors within financial markets such as investors, rather than the real economy [

36] and it has facilitated the rise of the shareholder maximisation norm [

37]. The most recent economic crisis of 2007–2008 plays a role in explaining why the term has grown in popularity in the latest decade as it has been clear that the financial sector has systemic impacts with sectoral and temporal effects, across jurisdictions. However, financialisation does not only halter financial stability, but the focus on reinforcing financial growth also removes focus from investment in the real economy. In the context of the sustainability challenge, this phenomenon counteracts efforts in financing circular and innovative modes of business models that are necessary to enable a transition to a ‘strong sustainability’ regime.

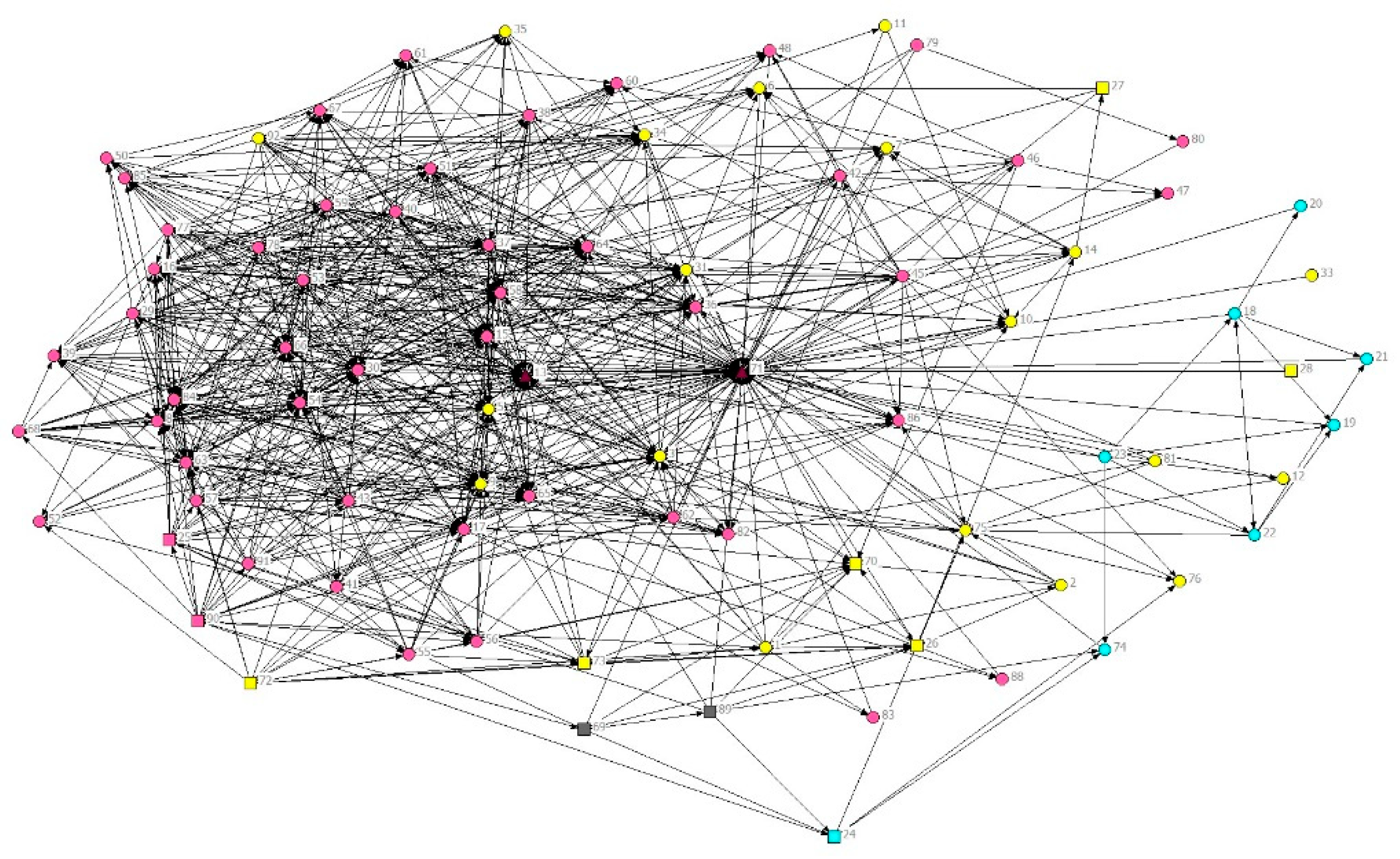

The approach of focusing on both hard and soft law means that it is possible to identify regulatory interconnectivity. For this purpose, I use social network analysis (SNA) in combination with semi-structured interviews. This approach enables a structural analysis of formal institutional processes complemented with qualitative analyses that together reveal the EU’s reflexivity of steering strategies and how they emerge into policy and law-making, with the potential of understanding why this is occurring, due to EU’s destinability and reflectibility. In this study, I, therefore, identify and assess the interconnectivity between legislative instruments, within and between EU business and financial market law. The mix-methods approach enables the identification of what is here denoted ‘policy hotspots’:

business and financial market-relevant policy areas that are the most promising ones due to political will and allocated resources to advance the EU’s commitment to sustainable development. These policy hotspots are the opposite of what are called blind spots in policy, and the term should be distinguished from how it is used in risk-management and life-cycle assessments and other kinds of policy analyses (the term is often used to prioritise potential actions that target the most significant economic, environmental and social sustainability impacts of a company, e.g., Reference [

38,

39,

40,

41]). I will also be analysing how these policy hotspots are central to the overarching system of the EU business and financial market law. To this end, I use SNA in combination with semi-structured interviews.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 introduces the rationale for using a mixed-methods approach consisting of SNA and semi-structured interviews. Special emphasis is given to the theoretical basis for the use of SNA in this particular study.

Section 3 presents the results of the SNA, followed by a broader analysis that takes into account the data collected through the interviews. This section also presents the ‘policy hotspots’ that emerged from the comprehensive study of EU business and financial market law. These findings are discussed in

Section 4 in the light of the literature. This section maintains that there are two possible sustainability pathways in the current policy debate on changing business and financial market law: the Sustainable Finance initiative and the Single Market.

Section 5 concludes this study.

2. Materials and Methods

In order to identify interconnectivities and policy hotspots in EU business and financial market law, I have used a mixed-methods approach consisting of SNA and semi-structured interviews. I constructed institutional networks through the use of citations representing proxies for links between legislative instruments and policy instruments and documents (e.g., References [

42,

43]). Naturally, legislative instruments cite other legislative instruments that their parties consider relevant [

42]. Citations usually appear in the preamble where the parties ‘note’, ‘recall’, ‘reaffirm’, ‘recognise’, ‘bear in mind’, or ‘take into account’ relevant legislative instruments [

42]. The use of citations as links is furthermore supported by Kiss and Shelton [

44] (p. 87) who argue that ‘the legal effect of texts that are cited could be extended to other texts in other legal instruments’. It would probably not be possible to analyse both business and financial market law and the large set of legislative instruments that such an analysis requires without a method such as SNA. Normally, SNA involves networks of actors. In this study, I use legislative instruments, which are viewed as dynamic and changing in different ways insofar as they to some extent have ‘autonomous institutional arrangements’ (see References [

42,

43,

45,

46,

47,

48]). However, it is crucial to combine SNA with qualitative analysis, as SNA does not necessarily tell us why structures look like they do, or inform us of activities taking place between legislative instruments or actors. I, therefore, use the interviews with EU institution representatives to make sense of the dynamic relationship between different policy hotspots. This research strategy allows me to identify how key EU sustainability policies interplay with EU business and financial market law.

The SNA consists of the main relevant legislative instruments in effect during the period 1964–2018. The method for selecting legislative instruments and policy instruments and documents is summarised in

Table 1 and the main legislative instruments were identified through systematic searches in the EUR-Lex database [

49]. Each legislative instrument was manually scanned and searched for citations to other legislative instruments. The selection process for identifying relevant policy instruments and documents, so-called soft law included (1) the use of data from interviews, and (2) the use of keywords in communications and strategies that have an impact on the sustainability performance of European business and finance actors. The interviews point to four policy areas of particular relevance: the Circular Economy (CE) Package [

50], the European implementation of Agenda 2030 [

51], EU Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) policies [

52], and the Sustainable Finance initiative [

18]. These policy areas and their interrelated legislative instruments were, therefore, included. What needs to be noted is that traditional policy areas related to sustainability such as environmental law, labour law, etc. were not mentioned as important for enabling sustainable EU business and financial market law.

The semi-structured interviews were crucial to establishing an understanding of how the chosen legislative instruments are co-evolving and to identify policy trends. The interviews were conducted with 20 informants who had knowledge of EU policy-making in the areas of financial market law, including securities, banking and finance and pension and insurance; business law including traditional company law competence and corporate governance, together with accounting and reporting; and finally sustainability-related areas such as CSR, Circular Economy and Agenda 2030. The interviewees were selected on the basis of their acknowledged expertise and by snow-ball sampling where each interviewee was asked to recommend another suitable interviewee to ensure the inclusion of representative individuals (see Reference [

53]). The research was conducted between January 2017 and May 2018.

The network data were analysed using the SNA software UCINET, visualised (Figures 1 and 2, 4 and 5), and its NetDraw tool [

56]. In order to create graphical representations of the systems, two

SNA measures were considered:

The

betweenness centrality measures the importance of a node. The importance was measured by calculation of the geodesics (i.e., the shortest path between two nodes, see [

57], p. 110). Essentially this means that nodes with high betweenness centrality are connected indirectly to many of the nodes via their links (acting as ‘brokers’). Betweenness centrality presumes that the nodes in the network have links in both directions [

57]. Regardless, the use of this measure is sensible and useful since information usually flows in both directions in reality.

The measure

eigenvector centrality measures the levels of connectivity of a node’s adjacent nodes, meaning that it captures which nodes have more connections to other higher scoring nodes [

58]. Betweenness and eigenvector centrality evaluate the impact of a node on the structure or transmission of information within the network [

58].

4. Policy Hotspots: Two Possible Pathways to Enhance Sustainability?

The analysis of the results shows that the ‘Sustainable Finance initiative’ outlines a potential pathway to the better integration of the sustainable development principle in EU business and financial market law. This agenda also represents opportunities because efforts and resources are being mobilised by EU institutions as well as Member States (MS). In the EC’s proposal for a taxonomy framework, it will be possible to find out which financial products contribute to environmental sustainability, covering—in addition to climate—protection of water and marine resources, protection of healthy ecosystems, pollution prevention and control, and transition to a circular economy, which includes material recycling and waste reduction. This is promising; however, we already see here that these themes do not cover all aspects of the planetary boundaries concept [

1,

2], in which the aspects around biodiversity loss are particularly of importance. Nor does it say anything about the social dimension of sustainability (however, the EC do have a plan for developing a taxonomy framework for social sustainability in the future). Furthermore, most of the other legislative proposals have the main focus on carbon; hence, they need to be broadened. The idea of finding out how to deal with climate change first and then expanding the policy approaches to other aspects of sustainability is not informed by the urgency related to other planetary boundaries. Rather, it is important to take on an integrated approach [

68]. Whether this initiative (as well as the sustainable finance initiative at large) will be successful in transitioning the financial sector and contribute to strong sustainability remains unclear.

This apparent contradiction of having a lot of political will and recourses backing up the Sustainable Finance agenda, while at the same time not being progressive and holistic enough, can be explained by deploying a genetic reflexive approach to governance as it helps to unpack this emergent process of the financialisation of EU sustainability policies. The EU have a particular relationship with finance not only due to the economic crisis but also because the financial sector constitutes one of the most important aspects of the famous “four freedoms” set out in the Treaty of Rome in which capital is one of these freedoms that can cross MSs’ boarders, now extended under the Single Market. This focus, I argue, is a natural result of the financialisation of the global economy, where the EU is one of the biggest markets. The approach of using finance to ‘green markets’ has been a viable option for decision-makers and these findings suggest that processes of corporate financialisation have magnified.

The EU’s tendency to compartmentalise, with each DG of the EC discussing their own traditional issues has furthermore a significant role in this matter. Despite how the EC organises itself through certain inter-services groups across the EC, some of the DGs seem to have more power than other DGs (e.g., [

69]). The reason may be partly due to the influence of the EC President’s personal preferences, leadership style and pattern of interaction with other members of the College that determines the view and the direction of the EC [

70]. The recent year’s Juncker Commission’s priority 1, ‘Jobs, growth and investment’ (see

Section 3.2.3) is a telling example. The notion of how corporate financialisation impacts policy outcome is in line with the assumption that the DGs that have strategic interest and power in EU business and financial market law is not the same DGs that may have the best sustainability competence. The societal processes of institutional fragmentation and shareholder maximisation norm have not only contributed to a research gap, but it seems to have resulted in a policy gap as well. However, the recent progress that follows with the Sustainable Finance initiative is showing that this may be changing.

Looking into the regulation of specific questions of the sustainable finance initiative, the findings show that the financial crisis has facilitated a new focus on certain legislation and on efforts to minimise short-term market mechanisms via new legislation such as in the Shareholders Rights Directive (node 35) and IORP II (node 91). While this is positive, it seems that the EU’s reflectibility of the past is creating a path dependency through the internalised notion of corporate financialisation. This path dependency has created policy approaches where the shareholder maximisation norm has been prioritised over others and facilitated an action agenda with mainly non-binding measures. These approaches do still inform and even steer the EC agenda on sustainability.

The ‘better regulation’ agenda consolidates this process as it through its programme often stopped statutory processes and policies on mandatory legislation. However, the main aim is to minimise the cost of law-making [

71], which is positive. Radaelli [

72] suggests that the better regulation agenda is a policy that has resulted in more business involvement in policy. This, in combination with the lack of trust between the MS, may lead to a process where the EC may be silent on the limitations of its own Research and Innovation Action and therefore overemphasise the outcome of its in-house empirical analysis [

72]. Businesses and MS may respond with advocacy papers camouflaged as impact assessments. According to Radaelli [

72], there is, therefore, a risk of getting ‘worse’ politics as a result of ‘better’ regulation.

Furthermore, market-oriented approaches in the case of financial market law are unlikely to substantively deliver on sustainability because of the institutional structure of financial intermediaries. The main reason is due to their practice of separate beneficiaries from the decision-making in capital allocation. Some of the biggest barriers to achieving strong sustainability are the voluntary codes of conducts for market actors. There is an urgent need for more binding, mandatory regulatory approaches in order to address private sector free-riding behaviour and mismatched resource allocation [

12]. Hence, the examples of regulatory intervention such as the one set out in the amendments of the Shareholders Rights Directive and IORP II are therefore not templates of what is needed to facilitate the disruptive transition of our markets that are needed to achieve the “safe operating space” for global societal development.

In addition, the power of the MS and the multilevel function of the EU decision-making process plays a significant role in this context. The study provides some preliminary evidence on the occurrence of a ‘progressive divide’ within the EU. The findings suggest that some MSs generally support the sustainable finance agenda such as France, Italy, Netherlands, the Nordics, and to some extent Germany, while other MSs may work towards maintaining the status quo. A conjecture from this, and in line with corporate financialisation processes, MSs with the largest financial markets seem to be the ones that are the most engaged in the Sustainable Finance initiative; e.g., the United Kingdom, France and Germany (Interviewee 19 and 20).

These processes further facilitate corporate financialisation that is encapsulated by the EU’s

reflectibility and

destinability in relation to its supranational to intergovernmental relations with MS. The structures around policy-making processes and law-making between the EU institutions affect the EU institutions’ self-capacitation. The interviews shed light on the role of Council of the European Union as through the MSs limit the integration of the sustainability principle in new legislation. In other words, the corporate financialisation norm creates path dependency that is institutionalised to a degree that, I would argue, limits the EU’s

destinability, i.e., its ability to create sustainable legislation. What the analysis suggests is that the social, technical and natural environment of today’s world economy—informed by corporate financialisation processes—seems to be embedded in multiple structures in the EU decision-making process, across the EU institutions and at MS level. This affects the EU institution’s self-capacitation that is ‘reflected’ in their notion of ‘ability-to-do’, in this case, sustainable business and financial market law. In addition, many of the most powerful corporations, interest groups and NGOs have the capacity to influence and shape the agenda within the EU (e.g., corporate capture in corporate sustainability practices [

73,

74]). This has additional effects on the EU’s ability to create sustainable legislation. However, such an analysis is outside the scope of this study.

4.1. Should the EU Rely on Finance to Tackle Unsustainable Business?

The key EU financial services directives, IORP II (node 91), MiFID II (node 30), and Solvency II (17) together with the regulations UCITS (node 8) and AIFMD (node 54) are all targets for purposeful intervention through the action points set out in the EC Communication on ‘Financing Sustainable Growth’ (node 90). Due to the continued process of corporate financialisation under the Sustainable Finance agenda, I argue that the centrality results “match” a real process of supplemental jurisdiction, and represent (by extension) interesting real-life processes (a citation link between legislative instruments could represent vital connections and/or the transposition and even implementation of certain general obligations to ensure activities under the jurisdiction or control of another legislative instrument). The centrality results show a potential for sectoral legal interconnectivity and may represent a process in which certain legislative instruments have control over other legislative instruments because of their relevance and how they are being cited.

MiFID II is the most prominent node in the betweenness and eigenvector centrality results. Yet, there are clear limits to what can be achieved through MiFID. The network connectivity results do not necessarily mean the wider diffusion of certain conceptual definitions or substantive provisions. Currently, there is also an absence of a ‘built-in’ sustainability principle in the MiFID and MiFIR instruments. The links to sustainability performance in MiFID are so far related to regulatory reporting to avoid market abuse and trade transparency obligations for shares. Policy solutions such as reporting and transparency do not offer a sufficient solution since such actions only deal with the symptoms of the sustainability problem and have, to date, not resulted in transitioning the behaviour of investors in financial instruments [

12].

An actual sustainability effect in the use of financial market instruments and through the regulations of MiFID II and MiFIR would entail the amendment of the instruments to include ESG criteria requirements for asset managers and their investment decision-making processes. Such a regulatory approach would also be linked to increased reporting requirements (links to accounting and non-financial reporting directives, nodes 1 and 3) and actions on tackling asymmetric power relations between the supplier and consumers of financial products and services. It is, therefore, promising that the EC with action 4 in its strategy aims to incorporate sustainability when providing financial advice where both MiFID II and IDD and its delegated acts will be amended, ensuring the inclusion of sustainability preferences in the suitability assessment. Based on these delegated acts, the EC is inviting ESMA (see regulation No 1095/2010 that established ESMA, node 66) to include provisions on sustainability preferences in its guidelines on suitability assessment. This may have positive effects as the EC authorities’ supervision influences the MS’s supervision of authorities’ action on sustainability.

The review of Solvency II (node 17) will also involve the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) (see regulation no 1094/2010, node 65 that established the EIOPA) in order to provide an opinion on the impact of prudential rules for insurance companies on sustainable investments. The embeddedness of the 1094/2010 regulation’s network in the eigenvector centrality results indicates that such an intervention could have positive and systemic effects on insurance and pension legislative instruments.

Another interesting section in the EC’s strategy for sustainable growth is the provision under action 7 to ‘[clarify the relationship between] institutional investors’ and asset managers’ duties to address sustainability considerations:

The proposal will aim to (i) explicitly require institutional investors and asset managers to integrate sustainability considerations in the investment decision-making process and (ii) increase transparency towards end-investors on how they integrate such sustainability factors in their investment decisions, in particular as concerns their exposure to sustainability risks.

Several pieces of legislation will be affected by these actions, including Solvency II, IORP II, UCITS, AIFMD and MiFID II. In line with the critique laid out by the HLEG [

62], Cullen and Mähönen [

12] highlight how many of the current rules result in fuzzy and inconsistent actor behaviour across jurisdictions. This means that it will be important for the EC to engage in harmonised action in furthering the work on fiduciary duties under action point 10.

The analysis suggests that the Sustainable Finance agenda has been given the role as the main driver of sustainable change, an indicator of how corporate financialisation affect the EU’s sustainability policy. Despite all positive aspects of the trends of sustainable finance, it remains to be seen whether the agenda will be successful in transitioning the financial sector so that it will contribute to strong sustainability goals. The agenda is lacking systemic considerations and there is a need to include market actor behaviour both in Europe and beyond. A transition will require mandatory regulation and legislation that steer market behaviour in a more stringent way.

4.2. Alternative Strategies? Looking at the ‘Real Economy’ to Address Unsustainable Business

The findings indicate that the existing framework related to the Single Market remains high on the agenda, even though it is not as visible as the Sustainable Finance initiative. The case of the Single Market is also relevant in light of Wiesbrock and Sjåfjell’s [

4] analysis of Article 11 of the TFEU and the possible cross-sectoral integration of the sustainable development principle. In the network (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2), the Directive 2006/123 EC on services in the internal market (node 81) is linked through its Article 1 to Article 2 of the Treaty of Rome on sustainable development (now Article 3 of the TEU), which can then be translated into a basis for the rule articulated in Article 11 of the TFEU.

The Single Market intervenes with the CSR agenda as well, not only through its functioning in the real economy but as a significant node in the network and also in terms of when these policy agendas were established (in 2011). The relative prominence of the EU Communication on CSR in the betweenness centrality results (

Figure 1) is especially interesting since it highlights the continued relevance of this agenda and outlines a basis for pressing it ahead, despite fluctuations in political will. The critique of the EU’s implementation of Agenda 2030 articulated by interviewee 9 is also interesting since the CSR agenda could be complementary in its focus on social sustainability. The topic of human rights and the systemic thinking in relation to corporations’ supply chains are well acknowledged and established within the CSR community internationally and is a topic that the EU needs to better address in its sustainability policies (e.g., References [

75,

76,

77,

78]).

However, it is suggested that the international CSR movement has had a role in maintaining the status quo in corporate practices as it has inadvertently reinforced shareholder primacy (e.g., References [

79,

80,

81]). The reason is that the agenda does not offer the tools to encourage corporations to transform their business models because CSR is separated from corporate governance. Therefore, the agenda has played a role in systematically narrowing down corporate purpose, and it has given little room to engender real corporate sustainability practices. Corporate sustainability requires a dismantling of the shareholder maximisation norm. Hence, whereas the CSR has been a useful agenda, it is still a ‘business-as-usual’ action agenda for weak sustainability.

The agendas related to the functioning of and possible synergies between the actions of the Single Market and the CE package are, however, promising. The potential for harmonised rules and EU-wide standards for products manufactured by recycled materials could create greater business opportunities and should, therefore, be further researched.

In order to enable strong sustainability in which there is a need for radical thinking to challenge the current economic realm, the solutions need to go beyond current market solutions. As discussed in the outset, financialisation reinforces the simple focus on financial growth, which removes the focus from investment in the real economy. In addition, this development has reinforced the rise of the shareholder maximisation norm and has mainly benefited actors within financial markets [

36]. A ‘desired future’ within the “safe operating space” for global societal development [

1,

2] requires strong sustainability but what does this mean in the context of the two alternative pathways in EU business and financial market law? The Single Market pathway encapsulated by the Single Market, the CSR agenda, and the CE agenda offer solutions that directly influence business conduct. The Sustainable Finance initiative only influences business conduct indirectly through the financial sector. Furthermore, the Single Market pathway facilitates a systems thinking framework in the real economy as its focus on supply chain management, across the EU and beyond, if implemented correctly. More concretely, this could facilitate circular and innovative modes of business models in which a notion of both environmental and social sustainability could be integrated, including labour rights and human rights principles. From a strong sustainability perspective, this pathway might offer solutions better aligned to the theoretical assumptions about what strong sustainability is and needs to entail. However, it is not clear whether this potential pathway will be able to promote sufficient change in corporate and financial behaviour on its own.

5. Conclusions

The reflexive governance analysis of corporate financialisation in EU business and financial market law shows that the identified policy hotspots represent two tentative pathways of action for achieving sustainability: the sustainable Finance initiative and the Single Market. It is especially the Sustainable Finance initiative that represents a potential pathway to improve the integration of the TFEU sustainable development principle in EU business and financial market law. The high interconnectivity in EU financial market law shows an established and developed legal infrastructure, which means that interventions in certain important legislative instruments such as MiFID and MiFIR could have forceful effects. The Sustainable Finance initiative is a policy area in which particular efforts and resources are being mobilised by EU institutions and MS, which is the reason it is classified as a policy hotspot. There are some, albeit uncertain, possibilities regarding the role of this agenda. Within the scope of this study, it is not possible to fully analyse this since the agenda is not fully implemented. However, more importantly, the study concludes that the agenda represent the amplified role of corporate financialisation in the economy, meaning that the Sustainable Finance initiative outlines a pathway that, despite the real potential, still implies an agenda furthering focus on the growth of finance and might result in retaining the shareholder maximisation norm.

The second tentative pathway outlining alternative non-financialised strategies related to Single Market policies, the CE agenda, and the CSR agenda. It is too early to say whether it offers a basis for corporate transformation either. Furthermore, at this point in time, the CSR agenda is not a political priority anymore and is therefore perceived to be a policy hotspot with decreasing importance. It has also been suggested that the CSR movement inadvertently has reinforced shareholder primacy. However, this agenda and its strategy represent content that is complementary to the EU’s implementation of Agenda 2030. Hence, the link with the business and human rights principles has the potential to revamp the CSR agenda and presents unique opportunities for developing the ‘social’ aspects of sustainability in EU business law. Within the pathway outlining alternative non-financialised strategies, there is some potential to integrate the CE agenda and the Single Market agenda. These policy areas have a higher level of political support and the potential synergies between them should not go unnoticed. However, due to our limited knowledge to date regarding such synergies, it remains to be seen what they will result in.

The EU has a particular relationship with finance through the financial crisis that instigated a revision of legislation and efforts to exclude short-term market mechanisms in new legislation. While this is positive, the identified policy hotspots in EU business and financial market law still lack action that supports binding, mandatory public law and regulations. Such policy action is much better at enabling ‘strong’ sustainability as there is a need for radical thinking in challenging the current economic paradigm where market actors are obliged to engage in the transition. Simultaneously, I argue that the EU’s action is path dependent through the internalised notion of corporate financialisation. This path dependency seems to be institutionalised to such a degree that I argue that it limits the EU’s ability to create sustainable legislation.

The findings indicate that we need to reform EU businesses and financial market law to facilitate systemic changes that can enable an economic transition. By building on these findings, it is possible to develop research questions that can guide future inquiry in this field of research. The directions of research are related to (1) the identified pathways for EU business- and financial decision-making and is concerning (a) the real potential of finance in sustainable development and (b) the potential of non-financial strategies of the real economy and, more specifically, the creation of synergies between Single Market policies and CE legislation. (2) There is a need to get a more comprehensive understanding of EU business and finance and the institutional-actor relationships that shape policy changes. There is, therefore, a potential to further analyse these fields of law in relation to sustainability whereas the performed mapping of the EU business and finance legislative landscape could be a useful reference point. There is furthermore potential to link this analysis to social-ecological systems analyses in which more specific sustainability problems could be linked to economic activity that is regulated directly or indirectly by the multiple legislative instruments from the network map. There are three research questions stemming from this paper: What are the most promising actions of the Sustainable Finance agenda for scaling up sustainable market behavior? How can the Single Market be used to scale up CE? How can the comprehensive map of legislative instruments in EU business and financial market law be used in other studies?