Examining the Moderating Effects of Work–Life Balance between Human Resource Practices and Intention to Stay

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Job Embeddedness

2.2. Organizational Commitment

2.3. Intention to Stay

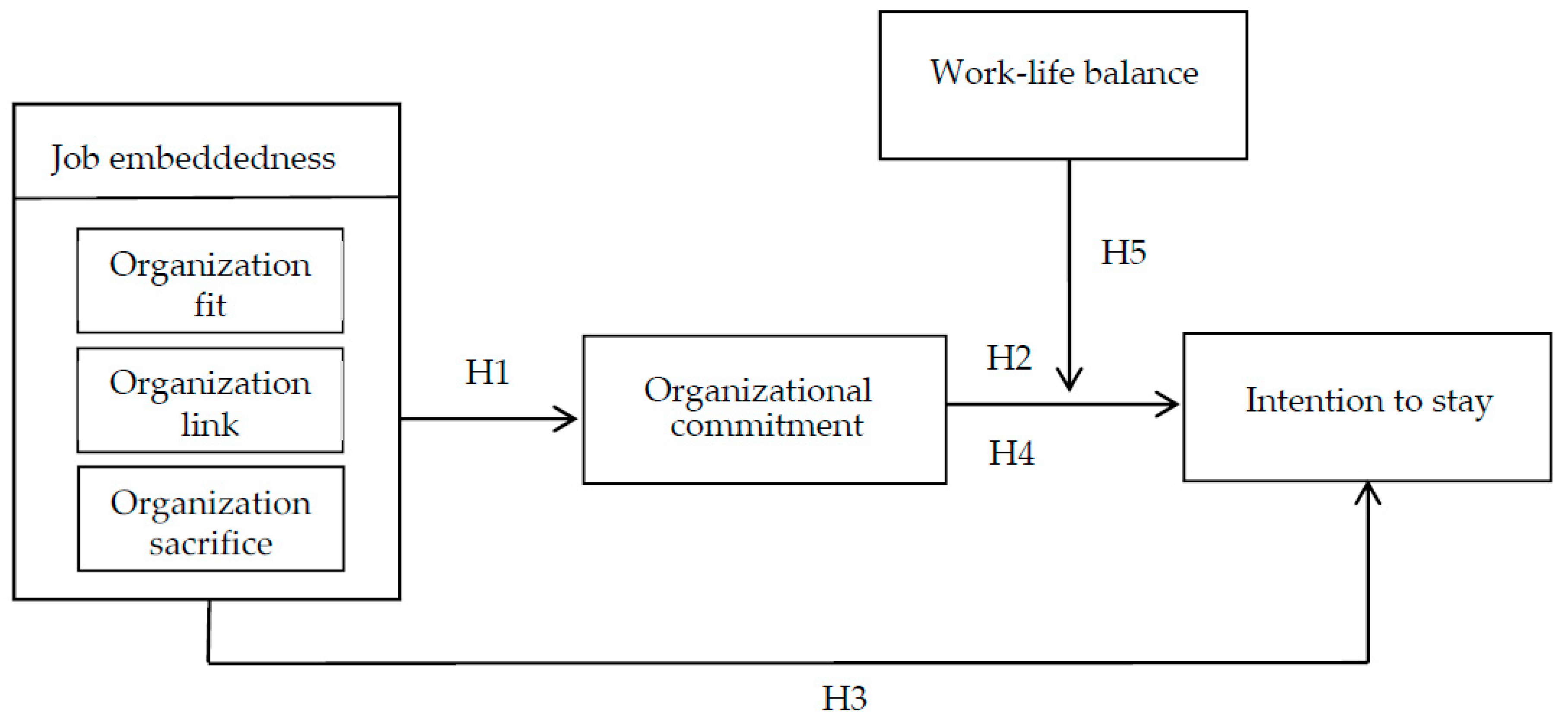

2.4. Relationships between Job Embeddedness, Organizational Commitment, and Intention to Stay

2.5. Moderating Effect of Work–Life Balance

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Measurement

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analyses

4.2. Structural Equation Modeling and Empirical Analysis

4.3. Testing Moderating Effects

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Findings

6.2. Limitations and Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stankevičiūtė, Ž.; Savanevičienė, A. Designing Sustainable HRM: The Core Characteristics of Emerging Field. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, D.; Jason, D. Job satisfaction and turnover intention: The moderating role of positive affect. J. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 139, 222–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zopiatis, A. Hospitality internships in Cyprus: A genuine academic experience or a continuing frustration. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. M. 2007, 19, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beggs, B.; Ross, C.M.; Goodwin, B. A comparison of student and practitioner perspectives of the travel and tourism internship. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport. Tour. 2008, 7, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M. Student perspectives on the quality of hotel management internships. J. Teach. Trav. Tour. 2006, 6, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.; Uludag, O. Conflict, exhaustion and motivation: a study of frontline employees in Northern Cyprus hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 26, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J. Hotel service providers’ emotional labor: The antecedents and effects on burnout. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, K.H.; Baker, M.A.; Murrmann, S.K. When we are onstage, we smile: The effects of emotional labor on employee work outcomes. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 906–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Ok, C. Reducing burnout and enhancing job satisfaction: Critical role of hotel employees’ emotional intelligence and emotional labor. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, G.; Bartikowski, B. Employee emotional labour and quitting intentions: moderating effects of gender and age. Eur. J. Mark. 2013, 47, 1213–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkin, T.R.; Tracey, J.B. The cost of turnover: Putting a price on the learning curve. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 2000, 41, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.W.; Mitchell, T.R.; Sablynski, C.J.; Burton, J.P.; Holtom, B.C. The effects of job embeddedness on organizational citizenship, job performance, volitional absences, and voluntary turnover. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 711–745. [Google Scholar]

- Thatcher, J.B.; Stepina, L.P.; Boyle, R.J. Turnover of information technology workers: Examining empirically the influence of attitudes, job characteristics, and external markets. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2002, 19, 231–261. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J.Y. The analysis of employees’ turnover model. J. Econ. Manag. 2003, 5, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, T.R.; Holtom, B.C.; Lee, T.W.; Sablynski, C.J.; Erez, M. Why people stay: Using job embeddedness to predict voluntary turnover. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 1102–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Crossley, C.D.; Bennett, R.J.; Jex, S.M.; Burnfield, J.L. Development of a global measure of job embeddedness and integration into a traditional model of voluntary turnover. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holtom, B.C.; Inderrieden, E.J. Integrating the unfolding model and job embeddedness model to better understand voluntary turnover. J. Manag. Issu. 2006, 18, 435–452. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, G.B.; Fink, J.S.; Sagas, M. Extensions and further examination of the job embeddedness construct. J. Sport. Manag. 2005, 19, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langton, N.; Robbins, S.P. Organizational behaviour: Concepts, controversies, applications; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Angle, H.L.; Perry, J.L. An empirical assessment of organizational commitment and organizational effectiveness. Adm. Sci. Q. 1981, 26, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, D. Teachers and Their Workplace: Commitment, Performance and Productivity; Sage Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Shreya, G.; Rajib, L.D. Effects of stress, LMX and perceived organizational support on service quality: Mediating effects of organizational commitment. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2014, 21, 64–75. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, R.N.S.; Kralj, A.; Solnet, D.J.; Goh, E.; Callan, V. Thinking job embeddedness not turnover: Towards a better understanding of frontline hotel worker retention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, K.E. Employee Traits, Perceived Organizational Support, Supervisory Communication, Affective Commitment, and Intent to Leave: Group Differences. Master’s Thesis, North Carolina State University, North Carolina, NC, USA, 13 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tett, R.P.; Meyer, J.P. Job satisfaction, organization commitment, turnover intention, and turnover: Path analyses based on meta-analytic findings. Pers. Psychol. 1993, 40, 259–291. [Google Scholar]

- Price, T.U.; Rupp, S.W.; Posey, C.E.; Mueller, N.A.; Johnson, T.A. Functionally illuminated electronic connector with improved light dispersion. U.S. Patent 6,257,906, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee, M.; Stoltz, E. Employees’ satisfaction with retention factors: Exploring the role of career adaptability. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 89, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffeth, R.W.; Hom, P.W.; Gaertner, S. A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: Update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 463–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McShane, S.L.; Von Glinow, M.A. Employment relationship and career dynamics. In Organizational Behavior: Emerging Realities for the Workplace Revolution, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 552–555. [Google Scholar]

- Perryer, C.; Jordan, C.; Firns, I.; Travaglione, A. Predicting turnover intentions: The interactive effects of organizational commitment and perceived organizational support. Manag. Res. Rev. 2010, 33, 911–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, L.W.; Steers, R.M.; Mowday, R.T.; Boulian, P.V. Organizational commitment, job satisfaction and turnover among psychiatric technicians. J. Appl. Psychol. 1974, 59, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanova, C.; Holtom, B.C. Using job embeddedness factors to explain voluntary turnover in four European countries. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 19, 1553–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harari, M.B.; Reaves, A.C.; Viswesvaran, C. Creative and innovative performance: A meta–analysis of relationships with task, citizenship, and counterproductive job performance dimensions. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psy. 2016, 25, 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WeiBo, Z.; Kaur, S.; Zhi, T. A critical review of employee turnover model and development in perspective of performance. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 4, 4146–4158. [Google Scholar]

- Chatman, J.A. Matching people and organizations: Selection and socialization in public accounting firms. Adm. Sci. Q. 1991, 36, 459–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.T.; Wan, C.S.; Fu, Y.J. Qualitative examination of employee turnover and retention strategies in international tourist hotels in Taiwan. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 837–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Liu, D.; McKay, P.F.; Lee, T.W.; Mitchell, T.R. When and how is job embeddedness predictive of turnover? A meta–analytic investigation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, N.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, C.C.; Yu, Z. Inclusion and inclusion management in the Chinese context: An exploratory study. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Man. 2015, 26, 856–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalidass, A.; Bahron, A. The relationship between perceived supervisor support, perceived organizational support, organizational commitment and employee turnover intention. Int. J. Bus. Admin. 2015, 6, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.G. Do organizational socialization tactics influence newcomer embeddedness and turnover. J. Manag. 2006, 32, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiche, B.S.; Kraimer, M.L.; Harzing, A.W. Why do international assignees stay? An organizational embeddedness perspective. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2011, 42, 521–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.G.; Shanock, L.R. Perceived organizational support and embeddedness as key mechanisms connecting socialization tactics to commitment and turnover among new employees. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 350–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, I.S.; Salau, O.P.; Falola, H.O. Work-life balance practices in Nigeria: A comparison of three sectors. WLB Prac. Nigeria 2014, 6, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suifan, T.S.; Abdallah, A.B.; Diab, H. The influence of work life balance on turnover intention in private hospitals: The mediating role of work life conflict. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2016, 8, 126–139. [Google Scholar]

- Karthik, R. A study on work-life balance in Chennai Port Trust, Chennai. Adv. Manag. 2013, 6, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Soomro, A.A.; Breitenecker, R.J.; Moshadi Shah, S.A. Relation of work-life balance, work-family conflict, and family-work conflict with the employee performance-moderating role of job satisfaction. S. Asian J. Bus. Stud. 2018, 7, 129146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchmeyer, C. Work-Life Initiatives: Greed or Benevolence Regarding Workers’ Time? John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hubers, C.; Schwanen, T.; Dijst, M. Coordinating everyday life in the netherlands: A holistic quantitative approach to the analysis of ict-related and other work-life balance strategies. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2011, 93, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Beutell, N.J. Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayman, J. Psychometric assessment of an instrument designed to measure work life balance. Res. Pract. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2005, 13, 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Lyness, K.S.; Judiesch, M.K. Gender egalitarianism and work–life balance for managers: Multisource perspectives in 36 countries. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 63, 96–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulose, S.; Sudarsan, N. Assessing the influence of work-life balance dimensions among nurses in the healthcare sector. J. Manag. Dev. 2017, 36, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M.C.; Koch, L.C.; Hill, E.J. The work-family interface: differentiating balance and fit. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2004, 33, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, E.K.; Issa, R.R. Work-life balance and organizational commitment of women in the US construction industry. J. Prof. Iss. Eng. Ed. Pr. 2012, 139, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, M.A.; Sebastian Reiche, B.; Dimitrova, M.; Lazarova, M.; Chen, S.; Westman, M.; Wurtz, O. Work and family role adjustment of different types of global professionals: Scale development and validation. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2016, 47, 113–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauregard, T.A.; Henry, L.C. Making the link between work-life practices and organizational performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. R. 2009, 19, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumara, J.; Fasana, S.F. Work life conflict and its impact on turnover intention of employees: The mediation role of job satisfaction. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2018, 8, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Gardner, D. Factors affecting employee use of work life balance initiatives. N. Z. J. Psychol. 2007, 36, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Jaharuddin, N.S.; Zainol, L.N. The Impact of Work-Life Balance on Job Engagement and Turnover Intention. S E Asian J. Manag. 2019, 13, 106–118. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Factor Analysis. In Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th ed.; Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J., Anderson, R.E., Eds.; Prentice Hall: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: A global perspective, 7th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gieter, S.D.; Hofmans, J.; Pepermans, R. Revisiting the impact of job satisfaction and organizational commitment on nurse turnover intention: An individual differences analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2011, 48, 1562–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansel, A.H.; Froese, F.J.; Pak, Y.S. Lessening the divide in foreign subsidiaries: The influence of localization on the organizational commitment and turnover intention of host country nationals. Int. Bus. Rev. 2016, 25, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, A.; Gelfand, M.J. Will they stay or will they go? The role of job embeddedness in predicting turnover in individualistic and collectivistic cultures. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.T.; Liou, J.W.; Yang, H.N. Exploring the Effect of Psychological Contract on Work-Life Balance: The Moderating Roles of Social Support and Emotional Intelligence. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010, 10, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Noor, K.M. Work-life balance and intention to leave among academics in Malaysian public higher education institutions. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2011, 2, 240–248. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | M | SD | CR | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1. Organization fit | 5.118 | 0.808 | 0.91 | 0.54 | (0.890) | |||||

| 2. Organization link | 5.690 | 1.212 | 0.69 | 0.43 | 0.259** | (0.847) | ||||

| 3. Organization sacrifice | 5.026 | 1.005 | 0.90 | 0.63 | 0.723** | 0.259** | (0.864) | |||

| 4. Organizational commitment | 5.451 | 0.855 | 0.93 | 0.71 | 0.464** | 0.141** | 0.464** | (0.853) | ||

| 5. Work–life balance | 5.691 | 0.856 | 0.90 | 0.53 | 0.348** | 0.385** | 0.347** | 0.417** | (0.967) | |

| 6. Intention to stay | 4.459 | 1.585 | 0.93 | 0.76 | 0.566** | 0.226** | 0.556** | 0.706** | 0.492** | (0.945) |

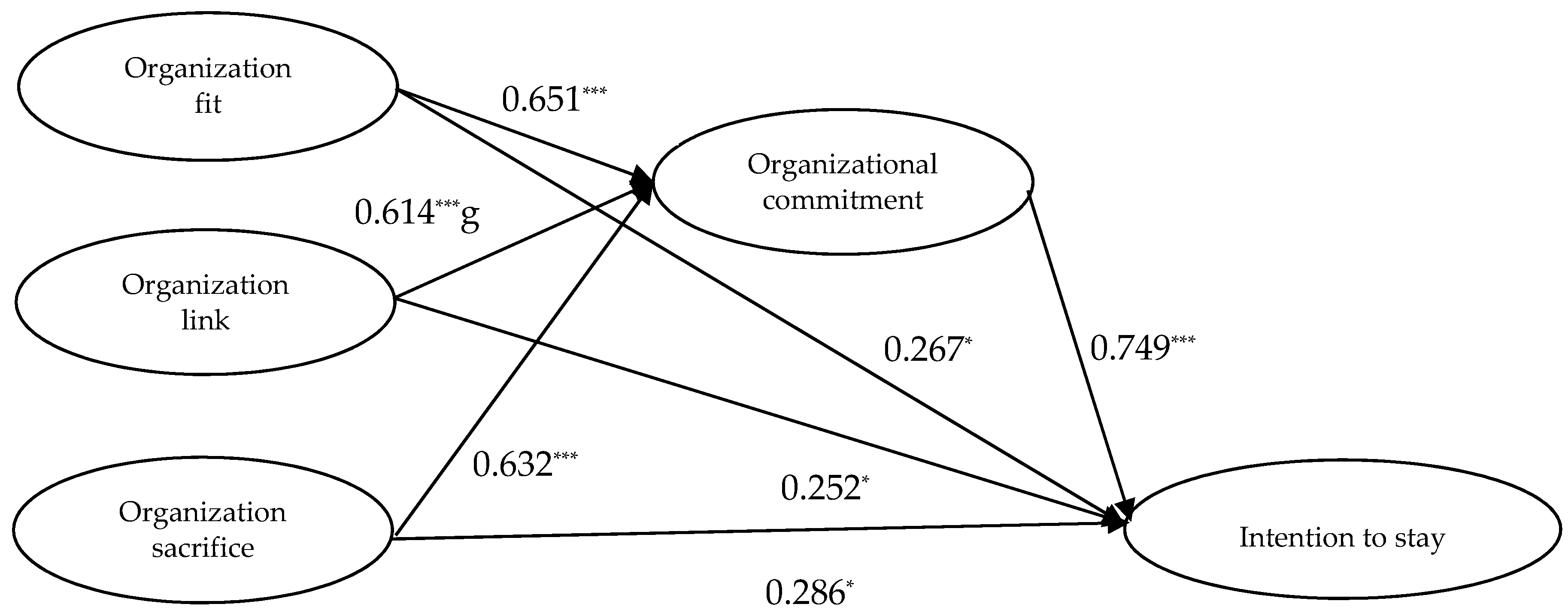

| Path | Standardized Regression Weight | t-Value | Hypothesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Directed effect of the integrative model | |||

| Organization fit → Organizational Commitment (γ11) | 0.651 | 5.784*** | H1a* |

| Organization link → Organizational Commitment (γ12) | 0.614 | 10.838*** | H1b* |

| Organization sacrifice → Organizational Commitment (γ13) | 0.632 | 9.400*** | H1c* |

| Organizational Commitment → Intention to stay (β21) | 0.749 | 18.050*** | H2* |

| Organization fit → Intention to stay (γ21) | 0.267 | 2.008* | H3a* |

| Organization link → Intention to stay (γ22) | 0.252 | 2.006* | H3b* |

| Organization sacrifice → Intention to stay (γ23) | 0.286 | 2.552* | H3c* |

| Mediating effect of the integrative model | |||

| Organization fit → Organizational Commitment → Intention to stay (γ11 × β21) | 0.488 | -- | H4a* |

| Organization link → Organizational Commitment → Intention to stay (γ12 × β21) | 0.460 | -- | H4b* |

| Organization sacrifice → Organizational Commitment → Intention to stay (γ13 × β21) | 0.473 | -- | H4c* |

| χ2/df = 3.96, GFI = 0.912, AGFI = 0.917, CFI = 0.920, RMR = 0.031, RMSEA = 0.072 | |||

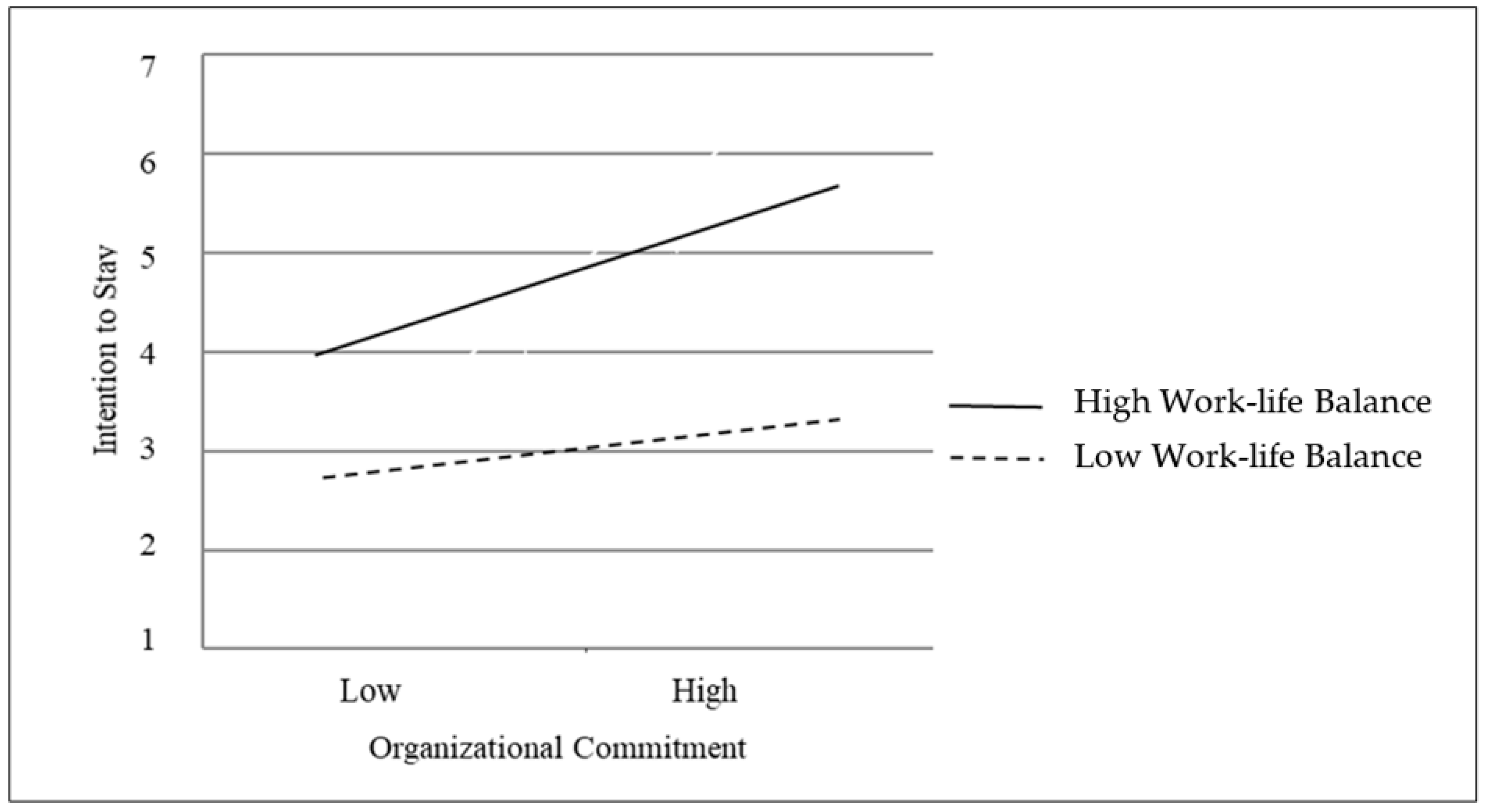

| Variables | Intention to Stay | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Step 1: Independent variable | |||

| Organizational commitment | 0.749*** | 0.257 | 0.137 |

| Step 2: Moderator | |||

| Work–life balance | 0.630*** | 0.366*** | |

| Step 3: Interaction | |||

| Organizational Commitment × work–life balance | 0.645 *** | ||

| R2 | 0.174 | 0.252 | 0.272 |

| △R2 | 0.078 | 0.020 | |

| F | 47.004 *** | 37.426 *** | 26.121 *** |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, H.-P.; Hsieh, C.-M.; Lan, M.-Y.; Chen, H.-S. Examining the Moderating Effects of Work–Life Balance between Human Resource Practices and Intention to Stay. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4585. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11174585

Chang H-P, Hsieh C-M, Lan M-Y, Chen H-S. Examining the Moderating Effects of Work–Life Balance between Human Resource Practices and Intention to Stay. Sustainability. 2019; 11(17):4585. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11174585

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Hsiao-Ping, Chi-Ming Hsieh, Meei-Ying Lan, and Han-Shen Chen. 2019. "Examining the Moderating Effects of Work–Life Balance between Human Resource Practices and Intention to Stay" Sustainability 11, no. 17: 4585. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11174585

APA StyleChang, H.-P., Hsieh, C.-M., Lan, M.-Y., & Chen, H.-S. (2019). Examining the Moderating Effects of Work–Life Balance between Human Resource Practices and Intention to Stay. Sustainability, 11(17), 4585. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11174585