1. Introduction

Urbanization is gaining momentum in developing countries, especially the largest, China and India, and cities are expected to contribute increasingly to macroeconomic growth. Thus noted Khanna (2016) [

1], stating “The rise of emerging market megacities as magnets for regional wealth and talent has been the most significant contributor to shifting the world’s focal point of economic activity.” In addition, urbanization represents a “transit out of informality” in economic activities, which Doner and Schneider (2016, p. 623) [

2] argue is an important condition for breaking out of the “middle-income trap”. However, city growth brings with it major problems—congestion, environmental degradation, and the inability of social and other amenities to keep pace with population growth among them [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

Extensive research has gone into this broad area, with theoretical models of growth supplemented by empirical work on specific cities. Although megacities have received much attention such as Beijing, Shanghai, New York, and so on [

10,

11,

12], smaller cities have not been ignored. Indeed, while megacities may garner the most attention by virtue of their size, the much larger number of smaller cities has been hypothesized to contribute more to growth and consumption [

13]. Out of this extensive body of work, a set of drivers of city growth and development has emerged.

However, growth is only a part of urban dynamics. Another important phase is stagnation and decay. Examples of these are the housing smoke-stack industries in Europe and the United States. Although less researched, studies have been conducted on the causes and impact of urban decay [

14,

15]. A third group of cities have grown, declined, and rejuvenated themselves, falling under the rubric of “urban renewal”. This process has varied from occurring within a single generation to taking centuries. The literature contains accounts of both successes and failures, for example, Quanzhou in China [

16], and Malaga and Kemeraltı, Izmir [

17].

More recently, a new city experience has been documented, especially in the context of the gradual liberalization of China. The Chinese state, which plays a major role in the country’s city development, has built cities that have been minimally inhabited. Dubbed “ghost cities”, international media has been quick to cite these as evidence of the ills of state planning. These claims notwithstanding, academic studies of their causes and impact have been few and far between. Indeed, until search engine Baidu used spatial data on its 700 million users to locate these cities and their surrounding geography [

18], even the precise locations of these cities had not been determined.

Even with these data, the factors that account for this lack of growth, the social dynamics of the population around these cities and their impact on the surrounding areas remain unexplored. Through secondary data sources and the lens of stakeholders in one coastal residential area, Yintan which is a part of the city of Rushan was chosen because it has been designated a ghost city, but its status is disputed by the city government and even by researchers, who have characterized Yintan thus: “The houses are empty for much of the year, but densely populated during the tourist season (

Figure 1). This clearly shows Rushan as a tourism center rather than a ghost town.” [

18].

The overarching objective of this paper was to shed light on this phenomenon through reviewing the experience of Yintan. The specific objectives were (1) to recount the growth dynamics of a particular city, (2) to understand this phenomenon through examination of growth drivers and inhibitors, to show that characterization of ghost cities often represents oversimplifications, and (3) to draw lessons for research on the ghost city phenomenon.

This paper is organized as follows. The next section reviews theories of city growth to identify major growth drivers. The absence of these factors can be hypothesized as causing a lack of growth. In

Section 2, the conceptual framework and data are described.

Section 3 describes the development of Yintan town, Rushan city.

Section 4 assesses Yintan’s development in light of the growth drivers described.

Section 5 concludes, using Yintan’s experience to gain insights into China’s ghost city phenomenon.

2. Theories and Drivers of City Growth

Theories and Growth Drivers. Numerous theories of city growth exist, but have different theoretical underpinnings. That city growth can be explained from different theoretical perspectives means that however rigorous the theory applied, alternative explanations always exist. Thus, while Arnott (1979) [

19] lamented that studies of optimum city size had not taken into account spatial and utility-maximizing frameworks, his economics-based narrative represented only one of several explanations of optimal city size. Rather than stress rigor, we elected to visit a wide range of explanations of city growth, some of which are pertinent to the city under study.

One set of explanations is based on the role played by stakeholders in a city, an application of stakeholder theory, which is concerned with the interaction of participants in a particular project or activity to compete against other cities, leaving no role for stakeholders [

6,

20]. On the other hand, Logan and Molotch (1987, p. 32) [

21] argue in favor of the alignment of a city’s business and political stakeholders’ interest driving a city’s economic development. They dubbed this the “growth machine”. They also argued that in the process of development, small businesses and vulnerable residents were often disadvantaged. Wojewnik-Filipkowska and Wegrzyn (2019) [

22] similarly combined known concepts of stakeholder theory, sustainable development, and public–private partnership to develop management of city development.

A second set of spatially based theories recognizes that cities “are first and foremost

places—agglomerations of people—rather than economic and political units” [

9]. These spatial theories include concentrated zone theory, which postulates that cities grow outwards in a series of concentric circles [

4]. Because this theory did not fit all cities, even in the US, Hoyt and Davie in the 1930s propounded sector theory, according to which urban land use patterns depend on routes radiating from the city center, creating different economic sectors [

23,

24]. Contradicting the view that a city has a single center, Harris and Ullman (1945) [

25] argued in favor of the existence of several centers in their multiple nuclei theory. Mention should also be made of the central place theory, which postulates that settlements functioned as “central places”, providing services to surrounding areas [

26]. Other spatial theories or models have been advanced, each providing an explanation for some cities.

A third group of studies has focused on key drivers of city growth and decline. Having a geographical presence, location is clearly a factor. Proximity to markets and trade routes and shelter from unfavorable weather are all factors conducive to city growth. City size, the product of historical accumulation of wealth and resources, which gives a city a scale advantage and the depth of invested resources to compete with other cities, is also a driver of growth. Polese (2013) notes that the advantages conferred by location and size are quite stable—except for some major external developments, these advantages are seldom lost. Duranton and Puga (2014) remind us that aside from numerous growth factors, external shocks also determine the fate of cities, as do macroeconomic changes.

The accumulation of human capital can lead a city to grow, and in the process, nurture innovation and attract more human capital. Glaeser, et al. (1992) [

27] confirm the existence of knowledge spillovers in American cities. This link complements that between human capital and macroeconomic growth (see, for instance, Aghion & Howitt, 1992) [

28]. A second driver, closely related to the first, is technology [

7,

29]. The importance of technology has been enhanced by efforts in many countries to transform their cities to “post-industrial cities”, shifting from being natural- and physical-resource-based to being knowledge- and service-oriented [

30]. This transformation is occurring in Chinese cities (for example, Li, Wang & Cheong, 2016) [

31].

The virtuous cycle of city growth and human capital deepening/technological advance is just one benefit of agglomeration, in which the concentration of resources in one location makes for reduced cost and sharing of knowledge, among other advantages for enterprises [

32], p. 801.

Agglomeration also facilitates the provision of physical infrastructure. Literature on this area is so rich that Fang and Yu (2017) [

33] were able to summarize major viewpoints from over 30,000 research items on this topic to arrive at a tentative theoretical framework for defining urban agglomeration. Of this infrastructure, transportation plays a critical role [

7]. Cities with good accessibility and good connectivity have exhibited higher growth. Indeed, Polese (2013) argues that connectivity may be more important than human capital, since easy access can attract the latter. Duranton and Puga (2014, p.796) also argued that a good commuting infrastructure is helpful to city growth. Housing and urban amenities are also part of this infrastructure. The availability of amenities attracts migrants to the city (Rosen, 1979) [

34].

A final set of drivers are institutions and their policies and regulatory framework. As elaborated by Huggins (2016) [

35], all the drivers discussed previously require effective institutions. Hederson and Wang (2007) [

36] stressed the role of political institutions in facilitating the growth of cities. Doner and Schneider (2016) also spoke to the role of institutions as necessary for growth. In the Chinese context of decentralized governance, city administrations have considerable autonomy in driving their own development. However, as the Nanning example shows both provincial and central governments can play a pivotal role [

37].

The China Experience. Given China’s pace of urbanization and the hectic growth of megacities, researchers have given Chinese city growth considerable attention. A World Bank/Development Research Center of China’s State Council publication- proposed policies reforming and improving the country’s urbanization experience [

38]. Schneider and Mertes (2014) [

39] studied the growth of 142 Chinese cities, including megacities. Batisse, Brun, and Renard (2004) [

40] used a sample of 132 cities for the period 1992–1998 to explore the impact of trade openness, and found this impact to be limited to coastal cities. Tian et al. (2016) [

41] analyzed the expansion of 35 of China’s large cities, and found economics to be the main driver of their growth. Studies have also been undertaken of individual cities (for example, Li, Wang & Cheong, 2016a, 2016b; Wang, Li & Cheong, 2018). These studies covered existing cities that are experiencing or have experienced historical growth. Cities built that failed to live up to expectations have not been examined.

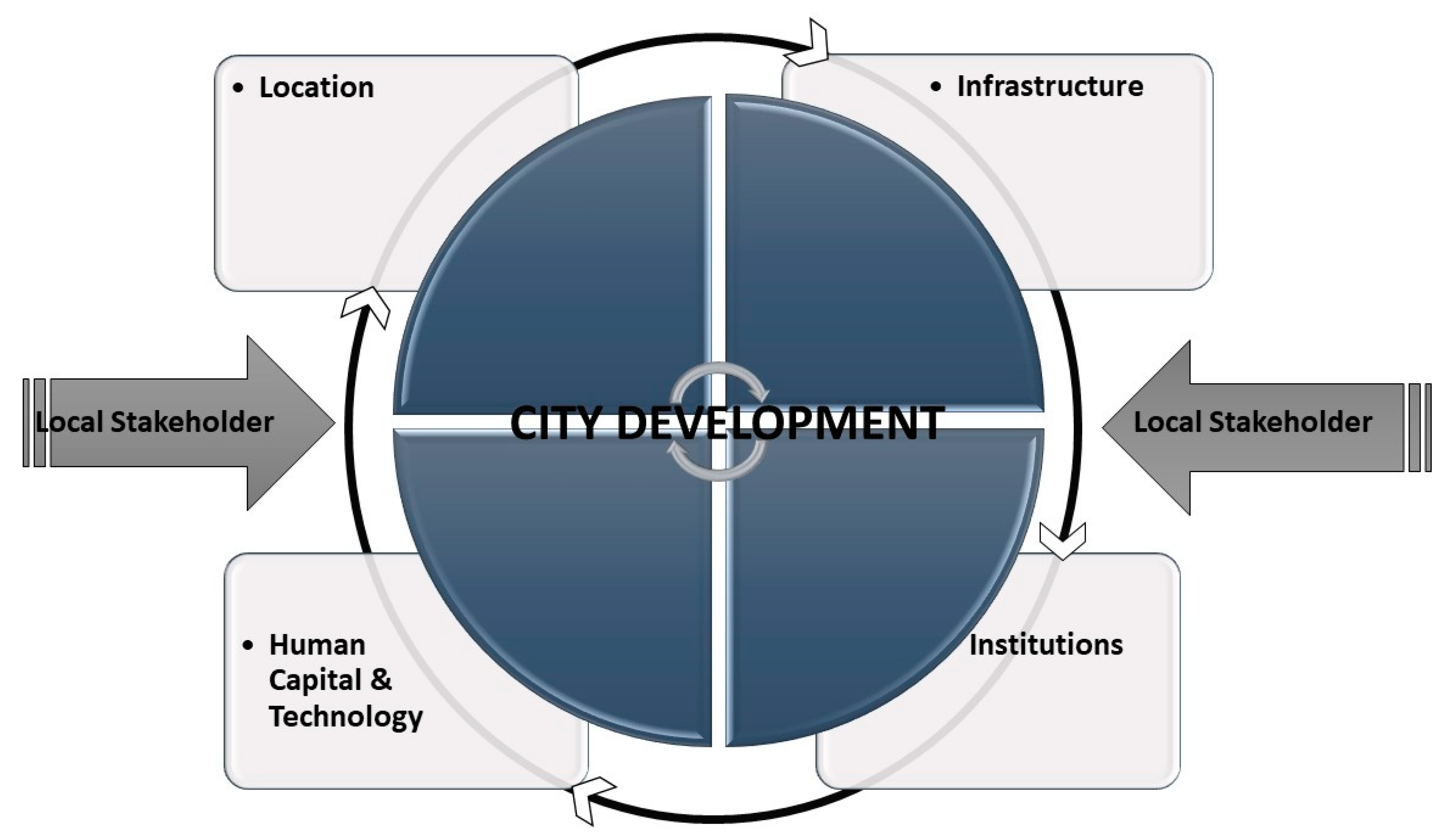

A Conceptual Framework. The above theories have their place in explaining city growth. In the context of this paper, however, their fundamental assumption that cities grow organically renders them less applicable. A more reasonable approach is to examine the drivers of city growth, concluding that growth failure has resulted from the lack of such drivers. In the section above, four groups of drivers were identified. These are location, human capital/technology, infrastructure, and institutions. At the same time, the role of stakeholders is vital—they contribute to whether growth drivers exist, and if they do, whether growth is in fact achieved.

In light of these considerations,

Figure 2 provides a graphical representation of the conceptual framework for the study of Yintan.

3. Research Methodology

The paper adopted a qualitative research methodology, involving the case study method, complemented by interviews and documentary review. The justification for adopting the qualitative research methodology was because city development as a complex subject requires local stakeholders’ involvement. The local stakeholders involve government, citizens, migrants, and so on. The interpretation of their behaviors has to be in the specific context, and therefore can hardly be approached through quantitative research. The case study approach enabled interpretation of social behavior under specific social economic contexts [

42]. Stake (1995) [

43] identified case study as a “holistic”, “empirical”, “interpretive”, and “emphatic” instrument in analyzing social affairs. Beyond it, Miles and Huberman (1994) [

44] depicted case study as an approach specifying phenomena in a bounded context. This article examines why and how ghost cities are developed; therefore, case study was the appropriate approach. The interviews with stakeholders, especially the local dwellers, enable understanding of their perceptions during planning and execution of the initiative, while documentary review as a complimentary tool was characterized as adding authenticity, credibility, representativeness and meaning by Scott (1990) [

45]. It allowed us to gain access to local government intervention in shaping the ghost city phenomenon.

Primary data were collected through 35 open-ended interviews and recorded on tape. The interviewees represented different stakeholders in the community who were likely impacted by the business and social situations described earlier. They included shop owners, visitors, and residents of Yintan and Rushan. Through questions such as “Why do you choose to reside in the city”, “What kinds of factors drove you to purchase a coastal house/apartment?”, “Why are you selling your house?”, and “What are the factors deterring you from the city?”, interviewees were asked to express their views as to why and why not they elected to stay in the city. The small, valid, and feasible sample reflected the fact that a large number of residents in the city were there during only a part of the year, and many were either unfamiliar with or reluctant to voice their views on the city.

The recordings were transcribed and data organized according to the research questions to be answered. Data organization should lead to the identification of concepts relevant to the topics of research. From concepts will emerge overarching themes for the specific research. Given that so little is known about the “ghost city” phenomenon, an appropriate analytical method might be grounded theory, which has the potential to yield original findings. That said, there is nothing novel in the above qualitative analysis, which was based on the case study method.

The role of the local government in shaping Yintan’s development was gleaned from secondary data in the form of government files and statistics and newspaper articles. The secondary data collected from government files ensured their validity. Some of the historical macroeconomic data and master plans for the city were hard to describe through interview, necessitating secondary-data-based research in that sector.

Rushan and Yintan

Rushan City is located in the southeast of the Shandong peninsula, covering 1665 square kilometers, with a population of nearly 560,000, not far from the larger cities of Qingdao, Yantai, and Weihai. It enjoys air and water quality that are above the national average [

8]. The city has a well-developed economy, its 2015 GDP of 47.7 billion Yuan having increased 8.4% over 2014 [

46]. Rushan City is also ranked among the top 100 nationally competitive counties (cities) in China [

47], thanks to its abundance of aquatic products, fruits, and gold [

48].

Yintan Tourist Vacation District (Yintan) is located on Rushan’s southeastern coast (

Figure 3) and is well-known for its excellent beaches, which have earned it accolades like “Oriental Hawaii” (Rushan News, 2017b) [

49]. Covering an administrative area of 65 square kilometers, its main tourist attractions include a lake, two islands, three rivers, four mountains, five bays, and six beaches. Major tourism projects, such as Furudonghai Cultural Park with an investment of 1 billion Yuan and the Peninsula Yacht Club with an investment of 400 million Yuan, are located in this area.

Before 1990, the 35,000-acre tidal lake hydroelectric power station in Yintan was a strategic and hence military controlled area, and land development was not allowed. This changed when the Yintan Tourist Vacation District was established in July 1992, and designated by the Shandong provincial government as a provincial tourist vacation district in July 1994. In November 2002, the national tourism administration designated it as a national AAAA tourist zone. Passing the ISO14001 environmental management and ISO9001 quality management system certifications, Yintan became the first of two certified tourist vacation districts in Shandong Province in the first half of 2003.

Yintan was then merged with Baishatan Town to combine tourism with industry in an enlarged urban zone. Further consolidation in 2012 saw the creation of Binhai New District, with a total area of 349 square kilometers that includes Yintan Tourist Vacation District, Big Rushan Tourist Vacation District, Haiwan New Town, Emerging Industrial Park Food, and Biological Science Technology Industrial Park [

50]

4. Growth Drivers

While the key growth drivers for Yintan are shared by other cities, they are specific to the city, as revealed by respondents interviewed.

4.1. Location

Yintan is blessed with natural endowments, and located close to prosperous Rushan and the cities of Qingdao, Weihai, and Yantai a little further afield. Being well behind these cities in industrial development has been to Rushan’s advantage—it boasts an environment far superior to these cities. That it was under military control that allowed no development undoubtedly contributed to its pristine natural environment. Environmental protection was maintained by the Rushan government after demilitarization, with only green industries allowed to be developed. Recognition of this achievement came in the 21st Session of the UN Conference on Climate Change held in Paris in November 2015, when the Chinese government promoted “Big Rushan Ecological Rehabilitation Project” as its model for future city development [

51].

These geographical assets were clearly on the minds of many Yintan residents interviewed; they considered these assets the most important reasons for locating there—the scenic view, clean air, natural surroundings, and seaside location all singled out for mention. Beyond the environment, the lower cost of living has also been cited as a favorable factor. Two typical comments:

“I prefer to stay here rather than in my hometown. As a retiree who suffered from bronchitis for years in my hometown, this air does me a lot of good.”

“I enjoy the ocean climate here during the summer. It is much cooler than in my hometown … I only come once a year and stay for vacation.”

However, geography/location is a double-edged sword. Despite the pristine environment, some are bothered by humidity.

“It is quite humid with the southwest mind from the ocean. So for those who suffer from arthritis, the weather may worsen the condition.”

Others complained about Yintan’s distance from their hometowns. Still others were put off by social distance—that incoming residents were dominated by people from northern China, not unexpected because Yintan is located closer to northern than to southern China. One interviewee complained:

“I feel homesick since few people here understand my dialect...With few friends and activities, it is quite boring to stay here. The priority for me is not only about the environment but the social community.”

For those with family members remaining in their hometowns for employment or other reasons, only limited durations of stay are possible:

“I seldom come, since it takes quite a long time to travel and I have not yet retired. Even after retirement, I may not be able to stay for a whole year as my children are all in Jiangsu.”

These challenges are faced by other similarly endowed cities and have been shown not to be intractable. That they have remained to affect Yintan’s image is a measure of the institutional challenges discussed next.

4.2. The Institutional Domain

Given the above framework, arguably the most important driver for state-led development is institutions. Of the three levels of government, the municipal government appears to be the most important driver of Yintan’s development. If challenges to growth were to be found, it should be at this level.

From a planning perspective, up to 2005, this government had no coherent plan beyond establishing it as a tourist vacation locale. Spending went into developing urban infrastructure and promoting real estate investment and tourism projects. Only after 2005 did the Rushan government see the need to develop complementary industries, and incorporated Baishatan Town as the industrial backyard for Yintan.

From 2012, it was determined that Yintan’s industrial sector should consist of developing the health care and pension service industries to revitalize Yintan’s real estate sector [

52]. To boost both the tourist and industrial sectors, the government also integrated Yintan into Binhai New District. Thus, the second stage involved redistricting as much as improvement of Yintan itself.

However, even these initiatives were more reactive than proactive, all spurred by external policies and developments. For example, Yintan’s adoption of tourism as a growth strategy in the early 1990s was simply a response to the national strategy of developing tourism as a new economic growth driver. The reliance on real estate development likewise echoed the nationwide liberalization of the real estate market, which was later to cause problems for the domestic economy. The resort to redistricting twice in 7 years is also symptomatic of a lack of institutional attention to long-term planning.

When it came to implementation, early efforts were limited to outsourcing to a large number of real estate developers to develop commercial and residential buildings. In canvassing the government’s achievements, Wang Tao, Deputy Director of the Administrative Committee of Yintan Tourist Vacation District, noted that more than 500 high- and mid-range villas and 26 hotels from a very small base were built in just four to five years of the implementation of the tourism development plan [

53].

When Baishatan Town was merged with Yintan, the only industry that expanded rapidly was construction due to the growing real estate market in Yintan. Indeed, founded in May 2007, the Rushan Chunhua Construction Engineering Co. Ltd., located in Jinhaiwan Industrial Park, Baishatan Town, grew to become the most important construction contractor in Shandong Province [

54].

Even with the government’s limited role, supervision and coordination were challenges. First, largely unsupervised real estate developers’ completed projects suffered from problems like unsound infrastructure and sub-par property management. Belated government recognition of these issues did not spur rapid corrective action. With real estate developers reaping the bulk of the profits, there was little incentive for the government to act. Purchasers themselves were not blameless—many were speculators and investors out to profit from rising property prices and were absentee owners who cared little about the living environment of the properties they purchased. Second, the lack of attention to economic synergy between sectors and activities promoted has meant the absence of agglomeration economies and little job creation.

The above woes have been felt by the new residents of Yintan. Those interviewed spoke of the lack of attention to operations maintenance, made worse by understaffed, poorly trained, and uncooperative bureaucrats. For instance, Binhai’s entire district administration, consisting of its police and other departments and its court of justice, is crammed into one government building, the Binhai Management Committee Building.

One interviewee complained that when he sought help from the local government office over the loss of his ID card, he was told the office had no authority over ID registry matters.

On the facilities themselves, residents complained of poorly regulated market areas, with vendors haphazardly found on roads obstructing traffic, and no checks on market prices charged. Third, the inhabitants complained about the lack of attention to preservation of the environment, with garbage strewn in public areas and ocean pollution caused by domestic sewerage. Fourth, government failure to screen incoming residents, according to those interviewed, has produced not only absentee owners, but also groups engaged in pyramid sales. Fifth, interviewees complained of the lack of monitoring of real estate developers, who had resorted to false advertising and predatory marketing practices. One interviewee noted:

“I bought the house because the developer promised hot water heating to those staying during winter. However, when I moved in during the winter last year, I found it was a lie. My appeal to the government was passed back to the developer with the advice to negotiate! The government protects local developers at the residents’ expense.”

The local government’s defensiveness when confronted with residents’ complaints also inadvertently revealed its institutional inadequacy. One official’s response when interviewed:

“The residential properties were developed initially to attract the investors, the developers and governmental entitles were to move in later. The city was not ready to be inhabited yet three years ago.”

was an open admission of the flawed belief that residents would be happy to move in before facilities were fully available.

4.3. Infrastructure

Despite its proximity to prosperous Rushan, access to Yintan is not particularly convenient. Travelers to Yintan have to fly or use the railways to the neighboring cities of Qingdao or Yantai, Coaches then ferry travelers to Yintan, a two-hour journey. The closest railway station is 30 km away. Transportation is just one of a range of infrastructure bottlenecks.

To be fair, the Rushan government did increase investment in supporting infrastructure, and it invested 2.6 billion Yuan for water, electricity, road, communication, cable, pipeline gas, central heating, sewage treatment, and other infrastructure supporting constructions. The “five horizontal and twenty longitudinal” local traffic network was formed. Some 40 million Yuan was earmarked for the construction of seaside leisure facilities and greening projects to improve Yintan’s attractiveness as a tourist destination. Still, infrastructure gaps remained. For example, the single hospital was a renovated township medical center. Despite occasional government efforts, a sound urban infrastructure and urban service system had yet to develop.

Recognition of these shortcomings led the Rushan government to add supporting facilities—a catering center, medical care, and culture and entertainment, and to provide pension services like green food supply—to unbuilt coastal real estate projects. Additionally, the government asked real estate enterprises to introduce professional health care and pension institutions. The objective was to revitalize the original buildings, increase health care and pension support, and develop the health care and pension industries [

55].

The government also introduced a large number of health care and pension service projects and encouraged local stakeholders to participate. This included the creation of large-scale professional health and pension institutions such as the Fuxing Elderly Apartment and Aizhiyuan International Pension Center, encouragement to enterprises to connect with outside health care and pension service institutions, and the building of hard and soft infrastructure (medical, food and beverage, housekeeping, and travel services) related to health care and pension services. For example, it completed the construction of an agricultural products exhibition center with the theme of providing health products.

Beyond these industries, Binhai New District has also attempted to foster innovative and high-tech industries to encourage agglomeration through human capital. In this regard, the government claimed as its achievements the Honglian Water Transfer Paper Project, the International Smart Care Center, and the Orbital Check-out Car Project introduced into Binhai New District. It also supported traditional industry projects to accelerate industrial upgrading [

56].

However, initiatives have been late in coming. In the meantime, residents complain constantly about the shortage of infrastructure and public facilities. For residential areas, the most common issue is the lack of a public heating system, causing most residents to leave during the cold weather. Those who stay have to incur high energy costs. Complaints of low hydraulic pressure during the peak water use times were also heard. One resident noted:

“I stayed in Binhai District one year during the winter and the electricity cost me RMB 1600 per month. The thermometer indicated only 4 degrees at home. Without adequate heating, it is too cold to stay here.”

The unsatisfactory road and street facilities were another focal point of complaints among the residents interviewed. Some streets were not lit at night, seriously damaging the city’s image. One resident complained:

“The main road, Binhai Road, is equipped with street lamps. The other areas, especially those away from the main road, were not. Few residents walk these streets even in the busy summer season.”

The inefficient public transportation system is another concern for residents. The void left by the poor public transportation system has, however, been filled by tricycle taxis. However, interviewees did not trust this mode of transport on grounds of safety. Also cited were the lack of entertainment facilities and shopping malls. Especially for the pool of younger people from whom skilled labor is drawn, these shortages deter them from coming to the district.

Officials’ defense of their requirement that (as stated by one official) “Private heating services can be accessed as long as 30% of a household orders the service, while public heating services require a 50% order rate” did not appear to recognize the hardships faced by early residents. Indeed, the same official acknowledged that “These (early) communities (had to) install their own systems”.

4.4. Human Capital and Technology

Human capital to drive Yintan’s growth was not an original priority for the Rushan government; as already indicated, it was content to allow real estate development to lead, taking advantage of Yintan’s tourism assets. Services and infrastructure to support real estate construction were given emphasis. With no strategy to attract talent, those moving to Yintan were mainly retirees or tourists staying only short periods between May and October each year. The following comment from an interviewee was typical:

“We run a small restaurant…Our business reaches its peak during the summer. It starts to fall off after October. We seldom have business during the winter.”

The types of people moving to Yintan are also shown by the predominant facilities in the town—hotels, property agent companies, small groceries, furniture shops, and home decoration outlets. The residents rely heavily on pension funds, or on seasonal and irregular business dependent largely on tourism.

Even with respect to real estate, Yintan is a destination for speculation rather than for investment. Speculation is fed by the absence of opportunities for businesses to which investment can flow and by the lower prices for residential units compared with the larger regional cities like Qingdao, which some believe have room to increase. Therefore, many of Yintan’s residents bought several houses rather than just one for accommodation, fueling real estate speculation. The consequent escalation in land values then offsets whatever incentives industries may receive to establish in the area.

For Rushan locals, Yintan is handicapped by high housing prices, a lack of business opportunities, and the influx of unsavory migrants. While a few chose Yintan because of job opportunities, their long-term preference was downtown Rushan. One resident noted:

“I bought a house in Binhai District because I work here...I just treat this place as a temporary habitat, and both my wife and son remain in the city downtown.”

The above suggests that left to its own devices, Yintan will not benefit from human capital and technology as a growth driver. There remains hope, however, that government plans, especially in integrating Yintan into Binhai to develop high-tech industries in the latter, might bring about an influx of talent. However, plans for Binhai made no mention of Yintan, and it is clear that they have not progressed to the detailed assessment of strengths and challenges that is a prerequisite to progress from planning to implementation. Even if implemented successfully, any result will be long-term in materializing. For the short- to medium- term, it is hard to imagine an increase to human capital or industrial upgrading for Yintan.

5. Conclusions: Insights into the “Ghost City” Phenomenon

Comparing Western descriptions of the ghost city phenomenon to a Chinese context, the definitions of it are totally different. Undoubtedly, it means a less-resided-in area. The ghost city phenomenon in Western countries is used to describe cities or towns abandoned due to urban decay and disaster, such as the mining town in Bodie, California [

57], Mojave Desert ghost town in Nevada, USA [

58], and so on, while China’s ghost town phenomenon has been criticized by scholars as the side effects of its rapid growth in the last decades. In particular, people have linked it with property development in China, treating it as an extensive land-use and urban expansion issue. Excessive discussions are occurring in the field of urbanization. In particular, this phenomenon provides strong evidence on how Chinese local governments survive on the rents from land lease to developers without considering rural-land encroachment and the creation of ghost cities or towns. More specifically, some of China’s ghost cities, such as Ordos, Changzhou, and Sanya, were shaped in China’s fast developing process as an instrument to obtain fiscal income for government. Beyond this, there is also a wish to expand these cities as new growth poles in the near future. Thus, they are never abandoned, distinguishing them from their Western counterparts.

Although classifiable as a “tourist city” rather than a “ghost town”, Yintan’s narrative sheds light on both. Extant writing on China’s ghost city phenomenon has depicted a monolithic Chinese state driven to deal with rural–urban migration through the construction of new towns [

59] that remained completely unoccupied [

60]. The result of this “megalomania” [

59] and “craziness” was “sinking China under a mountain of debt” [

61]. Yintan shows such characterizations to be reckless. First, the town’s development was driven by the Rushan government not to ease urban population pressure, but to respond to the central government’s call to develop tourism. Second, while developers shouldered the primary responsibility for development, not only did they not go bust, but they profited handsomely from their ventures. Third, while Yintan did not meet its residential objectives, it is not fully a ghost town. Finally, what has discouraged moving into the town has had nothing to do with China’s economic slowdown.

Secondly, Yintan is also less of a tourist town than a resort town. Rushan’s government had hoped that retirees would be attracted to the pristine environment and make Yintan their long-term residence. Although this potential is yet to be realized, Yintan shows that even tourist cities can leverage their natural assets to achieve greater occupation during the tourist off-season.

Third, far from showcasing the failure of state intervention, Yintan’s problems stem from the government’s failure to be actively involved in the town’s development, plans for which also showed the government’s reaction to national policies and economic changes. Having launched the initiative, little effort was made to monitor, let alone regulate, the activities of the developers who profited from their projects but left residents short-changed. This situation stands in sharp contrast to ghost cities like Ordos, where the local government played a dominant role in shaping the new urban complex through a comprehensive construction plan [

62].

Fourth, the Yintan experience shows that while the manner of its genesis and development has been different from most other cities and the theories explaining them, the same growth drivers—location, institutions, infrastructure, and human capital—contribute to the fate of Chinese state-sponsored cities. While the relative importance of each dimension varies depending on the main functions of the city and its resource endowments, the role of institutions is vital in its own right and in the effective deployment of infrastructure and human resources, as well as in leveraging locational advantages.

Fifth, as the interviewees’ responses showed, it is insufficient to focus only on physical infrastructure. Soft infrastructure—the facilities and organizations for social integration into a vibrant community—are no less important to retaining residents for the long-term and to overcoming the challenges of geography. An institutional infrastructure able to respond quickly to residents’ complaints and needs is no less important.

Sixth, the fact that the limited success in the provision of infrastructure to and acquisition of the appropriate human capital for Yintan points towards institutional weaknesses raises the question of why this was the case. One explanation is that the modest size of Rushan translated into equally modest institutional capacity in developing Yintan. This may explain why everything was left in the hands of developers. However, minimal involvement in development projects also means that many of the returns of development do not accrue to the government. In all the interviews, reference to government corruption has been conspicuous by its absence. Lack of benefits then produces further governmental indifference to Yintan’s development, reflected in interviewees’ complaints of bureaucratic indifference.

Seventh, the institutional and other deficiencies are not intractable, but small cities like Rushan may lack the resources to undertake remedial action. From a policy perspective, greater regulation over which city can build new cities/suburbs seems warranted. How effective this can be remains an open question however, given China’s history of highly decentralized administration and subnational autonomy.

Lastly, with the Rushan government finally aware of Yintan’s challenges, it has begun, since 2012, to take remedial action through greater involvement in Yintan’s future development. A brighter future may yet await Yintan in the years ahead. However, the challenges of the early years will need to be overcome with sufficient remedial action to reverse the negative perceptions the town has garnered. This will take time to accomplish.