Abstract

Sustainability has become one of the key factors for the development of tourism both nowadays and in the future. The need to integrate environmental, socio-cultural and economic factors is a consequence of the evolution of society itself, the introduction of new information and communication technologies (ICTs) and a new way of understanding tourism and the world in general. Tourists increasingly seek a unique quality in their travels and are better informed before deciding on a tourist destination to spend their holidays or leisure time. They want to have unique, memorable experiences, and because of that, they are willing to look for those destinations that can offer them something different. The generation of expectations is no longer the sole responsibility of companies and public and private organizations in destinations, since information may be in the hands of the individuals themselves who can share it in social networks, blogs, or on platforms such as Booking or TripAdvisor, among others. This forces companies and public and private organizations to rethink the way in which and when they relate to tourists in general. With all these considerations, one of the objectives of this study was to analyse the way in which sustainability interrelates with the generation of expectations, experiences and perceptions and the effect on the possibilities of returning to a tourist destination and even recommending it in social networks to friends and acquaintances. For this reason, the destination of Acapulco, Guerrero, Mexico, was chosen, a mature destination of sun and beach that, in recent years, has been immersed in a process of change where one of the axes is sustainability. This study used a convenience survey with 310 valid questionnaires with tourists who stayed more than three days in Acapulco during the months of December 2016 to February 2017. The questionnaires were completed at different points of the destination and by participants over 18 years of age. We used SEM (Structural Equations Modeling) and EQS (Structural Equation Modeling Software) for statistical analysis. The results of the study showed how expectations influenced experiences and the intention to return to the destination and recommend it (WOM), thus, we proposed a series of recommendations for public and private agents that manage this tourist destination.

1. Introduction

The concept of sustainable tourism emerged in the 1970s and 1980s, and since then, there has been increasing interest both by researchers and academics, as well as by tourists and professionals in the tourism sector [1,2,3,4]. The need to find management systems that are more efficient economically, socially and environmentally, both from the point of view of a company and public administration, as well as the sensibility of tourists and residents, is patently clear in today’s society. The management of tourist destinations as smart tourist destinations has advanced in this direction, reliably capturing all these sensibilities and needs, based on information and computer technology (ICT) [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12].

The need to create increasingly sustainable environments can affect, to a greater or lesser extent, the generation of a tourist’s expectations of their enjoyment of their holiday, both while travelling and during their stay in the chosen destination. It can be as much a consequence of the necessary preservation of the natural and scenic resources of the destination, as the restrictions to their unbridled enjoyment that derive from and are established by the characteristics of the destination. However, sustainability should not undermine the generation of memorable experiences for tourists, as these require that they can participate in sensations, emotions and experiences that are unique and which they can, if they wish, share with their closest social and professional circles. In addition, the generation of experiences may affect their desire to return to a tourist destination and to make positive recommendations in their social and professional environments. The objective of this study was to analyse these relationships, and to this end, a questionnaire was prepared and presented to 310 participants in the tourist destination of Acapulco (Mexico). Structural equation modelling (SEM) was carried out for the analysis, and the main results obtained were that the destination’s sustainability affects the way in which this is valued by tourists according to the expectations that condition their experiences in the destination, in the same way that these condition their intention to return and their future recommendations to social, family and professional circles.

According to authors such as Bramwell et al. [7] and Zolfani et al. [13], among others, there are still many areas for improvement within the discipline of sustainable tourism, and many challenges to be faced. Aspects such as the longitudinal nature of the studies, the use of big data, the role of private companies in this field, the need to adopt broader, multidisciplinary and transnational perspectives, and to continue working on empirical studies, are some of the considerations that have been made in this field by these authors. In this sense, this work was framed within the studies of the sustainability of tourist destinations, and aimed to improve the knowledge of tourist behaviour beyond the analysis here and now, to obtain information on expectations and previous perceptions of the sustainability of a destination and how these influence the perceptions and experiences of tourists. Its main contribution was the widening of the temporal field of analysis, addressing the before, during and after of the trip. Also, from an academic point of view, we seek to influence the behaviour of companies, different public administrations and society in general, to raise awareness and create a more responsible behaviour, as this is the only way to preserve our cultural, heritage, economic and social resources, both current and future.

2. Background

2.1. Sustainable Tourism

Although the World Tourism Organization established an environmental committee in 1978 to agree on the lines of work necessary to achieve tourism that respects the environment, it was not until the mid-90s when international organizations undertook different activities in favour of sustainable tourism, being a clear referent to the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development in 1992, organized by the United Nations [3,7,14]. It was a consequence of the rapid growth of tourism (in terms of volume and geographic coverage) during the development period of European economies after World War II, and the negative effects of the massive tourism development model that led to greater environmental awareness, beginning with the Brundtland Report [4,8,10,11,15].

It should be noted that the concept did not appear within the tourism industry or the initiatives of public bodies, but mainly in the academic field. From this perspective, authors such as Bramwell and Lane [12,16,17], and Krippendorf [18,19,20,21] were a reference. Thus, for example, Bramwell and Lane [12] were the first authors who, in the inaugural issue of the Journal of Sustainable Tourism, defined the term and described its role [7]. Krippendorf [19,20,21], through various works, was a reference for the English and Germans and Krippendorf, Zimmer and Glauber [21] were icons in the field of sustainability, being considered its founding fathers. Although there are differences between these works and their authors, all of them seek integration and interaction between tourism, tourists and the environment in general, seeking to create and live a beneficial experience for all parties involved [7]. They capture the zeitgeist—the Spirit of the Times—which was indirectly due to the discussion about limits to growth triggered by the creation of the Club of Rome in 1968 [22,23]. In this sense, the Brundtland Report [24] provided the first international recognition of the discussion on sustainable development.

As a result of this analysis of world tourism development, new sectors of tourism emerged, and new market niches were created, such as rural tourism, ecotourism, cultural tourism, agritourism and solidarity tourism, etc., all aimed at creating a holiday model in line with sustainable tourism. Although there are many definitions of sustainable tourism, an analysis of the existing literature leads us to the conclusion that most of the definitions of this concept incorporate aspects related to economics, concern for ecology and the environment and society [4,11,14,15,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32].

It is evident, therefore, that in recent decades there has been a growing concern to find formulas that are capable of balancing tourism activity with the development of sustainability, with a progressive social and governmental concern for environmental sustainability that should be considered in economic and social processes, given the importance that the preservation of the environment has for the stability and social profitability of long-term tourist destinations. To this must be added the importance not only of economic but also social and cultural factors of the tourism industry as a result of its greater diversity and the enhancement of existing tourism resources [14,33].

Therefore, it should be noted, in general terms and after all these previous considerations, that the development of the tourism sector ought to focus on creating links with the principles of sustainable development respecting the conservation of the natural environment by creating relationships with the local economy and considering the good of the local community at both a social and ethical level [34,35]. In other words, tourism must be a sustainable practice that contributes to economic development, social equity, cultural revaluation and the preservation of the environment [33]. Therefore, it should be highlighted that the sustainable development of the tourism sector is principally based on the attainment of three basic objectives that constitute its dimensions [1,2,36,37,38]:

- The ecological dimension, which includes objectives such as the preservation of natural resources, which are necessary for the tourism sector and the reduction of dangerous emissions generated by that sector.

- The economic dimension, which integrates objectives such as the contribution to the economic success of the local community, as well as the maintenance and optimal use of the available tourist infrastructure.

- The socio-cultural dimension, such as the creation and improvement of satisfactory employment in the tourism sector, the possibility of offering opportunities for relaxation to both tourists and local residents, the preservation and enhancement of culture and the local heritage, and an increase in the level of participation of the local population in the area of sustainable policy development.

From this three-dimensional perspective, it can be affirmed that the sustainable development of tourism is inclusive, since it is friendly and close to its natural environment when considering and promoting ecological processes and biological diversity, by strengthening the local economy and over time improving the productive processes and giving value to indigenous products [37,38]. All these are relevant aspects to support and favour the development of future generations in a specific geographical area. It also incorporates residents and local communities into decision-making processes and strategic development [9,39]. For some authors, the development of sustainable tourism is strongly focused on the maintenance and enhancement of the natural, environmental setting and on economic development, while social commitment and development do not show the same evolution rates [32,40]. In this sense, the contribution of Mihalic [41], who combines the concepts of responsibility (linked to the behaviour of tourists) and sustainability (both for the content of the concept and for its values), is the concept of “responsustable” tourism, that gathers from a more real perspective both the academic concerns and the real behaviours of companies and tourists, and that connects responsible behaviour with the concept of sustainable tourism, adding the value of sustainability to the concept of behaviour. To this end, she developed a model called Triple-A, which is divided into three stages: Awareness–Agenda–Action. This model begins with a phase of analysis and recognition of the situation, continues with a planning step and concludes with an action stage. In addition to better understanding a model of responsible tourism that is fundamentally based on sustainability, this model is also a useful tool for understanding how the process of a destination or responsible tourism company can implement the sustainability agenda.

2.2. The Tourist Experience

Like sustainability, the “tourist experience” is a fundamental construct in tourism research that has been investigated for more than 50 years [42] and where at least four changes have been seen from a simplistic perspective until reaching more subjective and complex interpretations of the concept [43]. The first studies during the 1960s understood the tourist experience as a unique experience that was different from everyday life. At that time, there were studies dedicated to the nature of experience in a general, critical way [44], and through other contributions such as those of Clawson [45] and Clawson and Knetsch [46], who pointed out that the tourism experience should include influences and personal results both before the holiday and after it, identifying the recreational experience as an experience that has five main phases: before the holiday, the journey to the destination, the stay, the return trip and the memories.

Later, in the 1970s, the concept of the tourism experience progressively evolved towards more complex interpretations [47,48], and above all, with the publication of works such as Cohen’s [49] on the phenomenology of tourism experiences that marked a point of inflection to recognize diversity within experiences, recognizing that there could be different tourists with different experiences. Later, in the 1980s, the author continued to investigate the understanding of tourists’ motivations, attitudes and behaviour [50,51], which showed the sociological foundations of tourists and their experiences [52].

Later still, in the 1990s, investigations into the concept of experience demonstrated its complexity through its subjectivity and sensory dimensions. Some researchers, such as Falk and Dierking [53] with their model of interactive experience, considered that experience is a person’s interpretation of situations in the culture and times visited. But above all, the work of Pine and Gilmore [54,55] stands out as an important study that has been the basis for further work [56,57].

Both Pine and Gilmore [55] through their “experience economy” concept, and subsequent researchers [56,57,58], have highlighted the main problems presented by the tourism experience due to the difficulty in measuring it given its multifaceted nature. Thus, companies must stop offering goods and services as such; rather, they should start attracting customers in a more personal and differentiated way by generating unique, memorable experiences [52]. From this perspective, the field of experience can be classified into two dimensions: a horizontal dimension that integrates active and passive participation (in the first, the client is largely the protagonist of the development of experience, while in the passive participation the degree of protagonist of the client does not influence the development of the experience) and a vertical dimension that measures the degree of connection or relationship with the environment and where two degrees of connection differ. On the one hand, the degree of absorption (collected by the how the experience mentally captures the client’s attention and where he experiences the event but does not alter it) and the degree of immersion, where the subject participates in the experience and is directly involved and alters the experience), creating four quadrants where different types of experiences could be integrated [57]:

- Education, which implies the active participation of the person, such as participation in sports activities or participation in workshops and seminars. It is an experience where the person, in our case a tourist, learns and extends their knowledge.

- Escapism, where the person is totally immersed in the experience, which implies being able to detach themselves from everyday problems through the active participation of clients in events that are fun, festive, religious or through their participation in the projects of non-profit organizations in the third sector.

- Entertainment, which involves passive participation and immersion in activities of a cultural or sporting nature, such as attending a classical music concert or a football match. It is an experience in which a passive absorption of experiences is carried out through the senses. In fact, many people associate entertainment with experience, which is why it is one of the most developed.

- The aesthetics that occur when clients are submerged passively in the experience, such as touring, swimming, sunbathing or hiking on vacations, etc. In these experiences, the subjects hardly affect the environment since they only participate in the observation and enjoyment of the place.

Therefore, the experience can be of an active or passive nature for the participant, either because concrete results are produced, such as learning or the development of skills or whether it requires interaction or not. Pine and Gilmore ([54], p. 98) claim that an experience occurs “when a company uses services intentionally, its products as accessories, and there is a commitment to customers to create a memorable event”. Stamboulis and Skayannis [56], based on the Pine and Gilmore [54] model, indicated that we are moving towards a more experiential type of tourism, where it is very important to incorporate all the information and knowledge generated in physical and digital interactions with the tourist at the destination to create tourist intelligence that permits the generation of unique, satisfying experiences for new tourists in a continuous physical and digital learning environment (e-learning). The intelligence that is generated is specific to the destination and is oriented to the user, thus providing a source of intangible competitive advantage (and therefore it is more difficult to copy and imitate), and where culture becomes a fundamental factor in generating value in an interactive, dynamic way. These experiences are not unidirectional but created jointly between the company (supply) and the consumer (demand).

In the same way, Prahalad and Ramaswamy [59] assert that consumers realise that they want to interact with companies and create value jointly, assuming a more active role, breaking the traditional market focused on the company and opening a new era of interaction in which all stakeholders are empowered thanks to the possibilities offered by ICT [60]. In this way, the co-creation of experiences represents a highly relevant concept for tourism and research into experiences [52,59,61]. The interaction can be generated physically or digitally, at different or simultaneous moments in the four areas of experience described by Pine and Gilmore [54,55]. Therefore, it favours the existence of a suitable environment for successful interaction between destinations and tourists in a more direct and credible way.

Following the analysis of the creation of experiences, Oh, Fiore and Jeoung [57] elaborated a scale of measurement and validated the four dimensions of experiences of Pine and Gilmore [54] in the tourism sector through a study of bed-and-breakfast establishments in the hotel sector. The authors collected data from both the point of view of business owners and their guests. The results obtained confirmed the dimensional structure of the four areas of experience and provided empirical evidence and nomological validity of these areas within the housing and tourism environments.

Tung and Ritchie [62], on the other hand, defined the tourist experience as “an individual’s subjective evaluation and undergoing (i.e., affective, cognitive and behavioural) of events related to his/her tourist activities which begins before (i.e., planning and preparation), during (i.e., at the destination), and after the trip (i.e., recollection)” ([62], p. 1369). Through in-depth qualitative interviews administered to 208 participants, these authors identified four dimensions of the tourism experience using a grounded theory approach: affect, expectations, consequentiality and recollection.

If we continue to analyse the components of the tourism experience, we can see that they are complicated and vary widely if we analyse the existing literature on the subject. Thus, for example, for authors such as Gómez-Jacinto, Martín-García and Bertiche-Haud’Huyze [63], the tourist experience includes intercultural interaction, tourist activities, quality of service and holiday satisfaction. Other authors point out that the tourism experience is composed of dimensions with a cognitive nature [64], emotional [65], social [66], and the sensescape or multisensory enjoyment of the tourist destination on the part of the visitor [67,68,69].

Authors such as Kim et al. [70] contributed the concept of the memorable tourist experience (MTE), which they defined as a “tourism experience positively remembered and recalled after the event has occurred” ([70], p. 2). It is generated selectively from real experiences and is influenced by the individual’s emotional assessment of holiday opportunities and helps to consolidate and reinforce the memory of pleasurable events experienced by the tourist while exploring the resources of the destination. They were also pioneers in developing a quantitative scale of 24 items to measure the MTE. This scale is composed of seven sections or domains: hedonism, refreshment, local culture, meaningfulness, knowledge, involvement and novelty. Subsequently, Kim and Richie [71] validated the scale interculturally with Taiwanese tourists.

Chandralabal and Valanzuela [72], on the other hand, went further and pointed out that past experience plays a very important factor in the generation of memories and their power to influence consumer decision-making. For these authors and based on the research of Hoch and Deighton [73], the level of memory becomes the most valuable source of information when a tourist decides to return to a particular tourist destination and has important repercussions on their future behaviour. These authors point out that the importance of storing past experiences in memory is relevant due to their impact on future purchase motivation, its value and reliability and its influence on decisions.

What seems logical and important is that tourist destinations should consider MTE as a factor of differentiation and creation of value for tourists, as these are built by tourists in their individual evaluation of subjective experiences [73,74] according to their expectations. Therefore, the role of destination management organizations (DMOs) is “to facilitate the development of an environment (i.e., the destination) that enhances the likelihood that tourists can create their own MTE” ([62], p. 1369), as relevant factors that make it possible to return to the destination and also speak well about it in social and professional circles.

2.3. Sustainability, Expectations and Experiences

The economic dimensionality of the world tourism industry has led to the creation of an increasingly competitive market, where marketing plays an important and growing role with the aim of improving these economic indicators, as a symbol of progress and welfare of the resident company of a tourist destination that seeks to obtain a commercial advantage [8,13,39]. From this perspective, a tourist destination can be considered to be a complex amalgam of tourism products and services [75] where they participate and, at the same time, create relationships between a varied set of existing attributes, interest groups and main actors, such as shopkeepers, hoteliers and restaurateurs, necessary for the co-creation of tourism experiences [52,59,61,76], as we have commented previously. In addition, it seems that there is a correlation between sustainability and competitiveness, since if sustainability is created and integrated (with the creation and commercialization of sustainable attributes creating a credible sustainability agenda) as a key element within a differentiated tourism package, the attractiveness of the destination increases and, therefore, can improve its competitiveness [77,78].

The effective commercialization of sustainability in destinations can potentially reduce the burden of perceived responsibility for the consumer and act as a key factor in their decision-making process, provided that other aspects such as price and quality are comparable [79], integrated into sustainability and promote its development and acceptance. It should also be kept in mind that sustainability encompasses all the elements that contribute to creating a complete tourist experience for all tourists alike [8,13]. For authors such as Yu, Chancellor and Cole [80], the role that residents represent for tourism sustainability is fundamental, and their involvement in the tourism planning process is crucial for the success of sustainable tourism development. Pulido and López-Sánchez [81], in a study conducted on the Costa del Sol in Spain, analysed whether there were significant differences in the way they generate their expectations and perceptions of a destination depending on whether tourists considered it sustainable or not, noting that tourists who considered the destination to be sustainable had higher expectations of it and that affected the way in which they valued the destination and their experience of it, which was quite different from those that considered the destination to be unsustainable.

The state-of-the-art research in sustainability of tourism has shown that there is an incipient literature that reflects the relationship between sustainability and tourist experience of visitors, so that the visitor generates greater expectations about a destination perceived as sustainable. However, there are gaps in the literature about the factors and variables of sustainability that generate expectations in the destination by visitors, that is, what builds their perceptions and expectations. But, in addition, little has been studied yet about the relationship between expectation and tourism experience in the field of sustainability, especially from disciplines such as marketing and tourism. Understanding of this aspect could provide useful knowledge for the creation and management of tourist products and destinations. Therefore, our hypotheses started from the premise that the sustainability of the destination significantly influences expectations and that, in turn, these expectations are general experiences along with the loyalty to the destination and its recommendation. Following these considerations, our first hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 1.

The sustainability of the tourist destination has a positive and significant influence on the generation of tourist expectations for a tourist destination.

2.4. Managing Expectations and Memorable Experiences

Together with sustainability, the concept of tourist experience, as mentioned above, has been the subject of interest in marketing literature in recent years and has become a fundamental factor for the success of tourism businesses, in the hostelry sector and the accommodation sector [82,83,84], and that was later incorporated into other areas such as cultural tourism or sports, among others.

The constant search for these experiences has given rise to a new profile of a more active tourist, with a more creative and participative role, who seeks to create and form unique and memorable tourist experiences, generating value and meaning through them as a vital part to living and travelling [84,85]. The management of experiences has also evolved significantly with the implementation of new information and communication technologies [86,87,88,89]. In this way, for example, the arrival of new technological devices and the development of specialised software has permitted the application of new technologies such as virtual reality (VR) or augmented reality (AR) through applications that can be downloaded to mobile phones and specific programs made available to tourists who visit them in certain cultural and scenic destinations, such as museums, exhibition halls, etc., that facilitate new experiences for tourists [90] and that help to generate a series of expectations of the visited destinations.

In this way, the design of the experience becomes increasingly important in the current context for all tourism organizations (corporate agents, public bodies, etc.) for whom it will be necessary to analyse and better understand the type of experience that tourists expect of them and how it can be facilitated at an individual level [91]. The complexity of the concept of experience is evident and is reflected in the tourism marketing literature [52]. Concepts such as expectations of experience [92,93,94] and memorable experiences [70] have appeared in recent years to try to better understand the concept. In this sense, for example, people generate tourism experiences in a different way based on the values, background, culture, attitudes and beliefs that they have received from the environment in which they live [58,95]. Tsaur, Lin and Lin [96] indicated that the expectations of a memorable experience motivate tourists to participate in tourist activities, which is very important, for example, for cultural destinations.

The relationship between expectations and the generation of memorable experiences is necessary to understand the latter. For example, Matolo and Salia [97], in an investigation that compared the expectations of tourists before visiting the Serengeti National Park (SENAPA) in Tanzania with the experience that was obtained when visiting it, found, after questioning 390 tourists, that there was a strong positive correlation between expectations and real experiences. Cartwright and Baird [98], in their book on the growth and development of the cruise industry, point out that the most common reasons for seeking, choosing and booking a vacation on a cruise are luxury and fun. As a result, these pre-purchase expectations give fundamental importance to the overall experiential value of cruise vacations. In addition, the characteristics of cruise holidays make them ideal for experiential benefits and allow tourists to have a unique and memorable social experience [99,100].

We have based this work on what researchers like Chiou, Wan, and Lee [92], Larsen [93], Sheng and Chen [94] and Andereck et al. [98] call experience expectations. The expectations of tourist experience are the result of the different types of interactions between tourists and tourist systems before the holiday. For example, consulting tourist brochures, visiting websites, specialized travel blogs and other more general sites, advertising in different digital and analogue environments or remembering the experiences from previous holidays or trips may result in expectations of tourism experience, which, in turn, can influence the real travel decisions of tourists [92,94,101]. In addition, the expectations of the tourist experience can influence the perceptions and experiences of tourists during the trip, the memories of the trip, and the loyalty to the place [93,94], therefore, it is a psychological phenomenon.

Larsen [93] in his review of the concept describes the tourist experience as a combination of highly complex psychological processes, in which tourist experiences incorporate aspects such as expectations, events and memories, and where there are influences between the three stages. According to Larsen [93], tourists expect that during their trip and stay there will be a series of events as a result of anticipated planning. Whether they occur or not and how they happen can influence the feelings and real memories during and after the visit, and precisely how they remember changes expectations for the next visit, creating a pattern that feeds back on itself.

It is precisely from this perspective of relative interpretation that Larsen [93] pointed out that experience is a type of subjective and personalized process, which is related to society, culture and even to different systems, and that in the case of tourist experiences, changes depending on the type of tourist and the type of holiday among other factors, so its study should be addressed from different disciplines such as marketing, psychology, culture and sociology. In a similar way O’Dell [84] expresses himself from the field of cultural sociology, in which tourists have ceased to be passive actors to become an active part of the design, search and creation of their own holiday, at all times seeking situations and events that motivate and satisfy them, becoming the main actors of their experiences, a fact that occurs more frequently among the new generations of millennial tourists, and that is included within the profile of the tourist 4.0, for example. Therefore, in order to carry out a study on the experiences of tourists, it must be done from the in situ observation of visitors and tourists, from close up instead of at a distance, in order to obtain better results.

Following the analysis of tourism expectations and experiences, Sheng and Chen [102] designed a questionnaire to analyse the expectations of visitors to the museum, based on the works of Schmitt [103], Larsen [93] and Falk and Dierking [53], which would allow us to learn more about the expectations and experiences of tourists. To this end, they carried out a preliminary qualitative analysis of the contents of travel journals by experts, students and researchers, and then, after the stages of debugging, reliability and trust, questioned a sample of 420 visitors to museums for subsequent correlation during the trip. The objective was to improve the level of understanding and content in this field, due to the lack of studies on the existence of common characteristics of experience, which would permit a better connection between expectations and experiences. Their goal was to analyse how they affected the prior expectations in the generation of experience during the tourists’ holiday to detect a pattern of common characteristics.

It should not be forgotten that a main objective of tourism research in general is to investigate what potential tourists perceive as the characteristics of a holiday that create a positive experience as a way to better match expectations with experiences. For Andereck et al. [98], expectations are preconceived perceptions, prior to the experience of the performance or attributes of a product, so it is important that companies that want to offer experiences to tourists know their expectations, as the evaluation of an experience is framed within the preconceived ideas of the tourists [104]. Therefore, the theory of expectation suggests that a travel experience that meets or exceeds the expectations of tourists will be positively remembered. Therefore, our second hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 2.

The expectations of tourists positively and significantly influence the generation of experiences in a tourist destination.

2.5. Memorable Experiences, Loyalty and Intention to Recommend

A bibliographic review reveals that travel experience positively influences tourists’ intention to return to a destination [63]. Weaver et al. [101] point out in their study that part of the variation in the assessment of the destination and in the intention to return can be attributed to previous travel experience and the characteristics of the holiday. Authors such as Woodside, Caldwell and Albers-Miller [22], Kim and Ritchie [71] and Kim [105] report similar findings: the intention to return to a destination, the intention to recommend and the generation of positive word-of-mouth recommendations are the result of previous positive experiences of tourists. Also, Marschall [106], in his work on the role of memory in tourism, points out that tourists like to return to destinations that they have fond memories of. For this author, memory is a crucial factor in the choice of a destination; it is based on the tourist’s experience in the destination and on sharing the experience with others after the trip, in particular, through sharing texts, memories, stories, photos and souvenirs. Tsai [107] and Kim [105], for example, from a sample of Taiwanese tourists, demonstrated the predictive validity of memorable tourist experiences (MTEs) on the future behaviour of returning to a tourist destination, as they found that five of the seven components on their MTE measurement scale (i.e., hedonism, involvement, local culture, meaningfulness, and refreshment) influenced behavioural intentions to return to the destination, participate in the same tourism programmes and promote word-of-mouth recommendations. Tsai [107], in his study of a sample of tourists who visited Tainan in Taiwan, for example, considered the value of culinary experiences as a fundamental factor in generating positive and unforgettable memories that affect future behavioural intentions to return to the destination.

For other researchers, not only the type of memory has an effect, but the number of visits made previously also significantly influences the future behaviour of tourists to return to a destination [108]. Lam and Hsu [109] corroborated this fact in a study carried out in the Chinese market, determining that the intention of tourists from mainland China to return to a destination such as Hong Kong was reinforced by the number of visits made in the past. Therefore, based on the above, our hypothesis proposal is:

Hypothesis 3.

MTEs positively and significantly influence the intentions of tourists to return to a tourist destination.

Hypothesis 4.

MTEs positively and significantly influence the intentions of tourists to recommend a tourist destination.

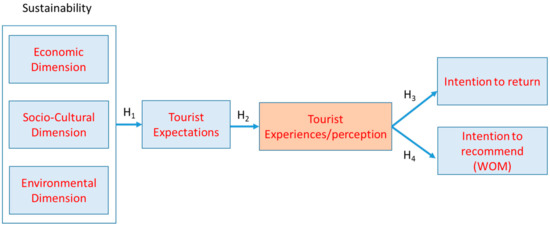

Taking all of these considerations into account, the model being tested is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Hypothetical model.

3. Methodology

In order to carry out the research, we initially based our study on the analysis of other works on sustainability and management of experiences in tourism to create the different measurement scales and then refined them to obtain a series of indicators that met the objectives of the study. To do this, we first conducted a literature search on sustainable development in tourism and the instruments for measuring it, that is, indicators and indicator systems. This initial work provided us with the theoretical and operational framework necessary to propose a system of indicators to measure the sustainability of tourism at a municipal level, which was better suited to the characteristics of the destination to be analysed, in our case Acapulco, a mature “sun and beach” tourist resort. This system of indicators stems from previous work on sustainability in tourism and the generation of expectations and experiences [42,57,81,94,98,102], intentions to return and intentions to recommend the destination (WOM—word of mouth) [110,111,112,113,114], among other authors and works. This system of indicators was verified by research experts and tourism consultants in the city of Acapulco and in the cities of Valencia and Castellón de la Plana in Spain. Subsequently, it was tested in the destination under study, Acapulco, to evaluate its effectiveness. As indicated in the bibliography consulted [2,115,116,117], to obtain a system that can be applied practically, it is necessary to collect significant local information, and a specific statistical treatment, which allowed us to analyse the degree of fit with the objectives of the study in each case. The distinctive local and territorial characteristics of the Acapulco tourist destination were also taken into account for the elaboration of the scales and their subsequent refinement.

In Table 1, we can see the technical data of the study. The sampling technique was not probabilistic for convenience because we collected data with questionnaires in different places in Acapulco, in access to beaches, public squares, hotels, etc. The sample was of 310 tourists and the fieldwork was carried out between December 2016 and February 2017, taking advantage of the winter holiday period (Table 1).

Table 1.

Technical data of the study.

For the scale of sustainability, made up of the economic, environmental and socio-cultural dimensions, different works in tourism were analysed from the existing literature [1,2,37,38,118,119,120], which allowed us to define a list of selected indicators structured according to a specific conceptual scheme based on the characteristics of the destination. This set of proposed indicators was validated and then fitted using the Delphi method after consulting several experts from the Autonomous University of Guerrero in Mexico, the University of Valencia and the Universitat Jaume I of Castellón in Spain. The initial set to measure the sustainability of the chosen tourist destination was 49 items selected for the three established dimensions, which after debugging the scale, was reduced to 13.

For the elaboration of the measurement scales of the generation of expectations and experience, several works were analysed [42,57,81,94,98,102,121]. For the scale of tourists expectations of experience, we used Sheng and Chen’s [94] scale that initially had 10 items and that were later reduced to 5.

For the tourist experience scale, the scales of Oh et al. [57] and Hosany et al. [121] were used and their subsequent debugging and adaptation reduced it to 4 items. Finally, for the scales of intentions of behaviour and recommendation (WOM) we used Croning et al. [110], Kim et al. [122], Stylos et al. [111], Wu, Cheng and Ai [113], Zhang, Wu and Buhalis [114], which after the corresponding stages of debugging and adaptation were reduced to 3 items each.

All the questions were made in a positive sense and items of different scales were measured with a Likert scale of 5 points. The destination chosen for the realization of the field work was the city of Acapulco, located in the state of Guerrero, on the south coast of the country, on the Pacific Ocean, 379 kilometres from Mexico City. It is one of the most important tourist destinations in Mexico, since it was its first international tourist port. According to the Mexican Secretary of Tourism (SECTUR), Acapulco is the most visited port in Guerrero and one of the most visited by domestic tourists, along with Cancun and Puerto Vallarta, among others. The municipality of Acapulco is the one with the highest GDP in the state with 38,592,218 million pesos. Tourism is the main activity, since it accounts for more than half of the economy, currently being the centre on the coast, with the fifth highest hotel occupancy and the eighth most visited city in Mexico [123].

Regarding the profile of the tourists who visit it, around 90% are domestic tourists, mostly from the Federal District, Toluca, Morelos and the State of Mexico [123]. This low rate of arrival of foreign tourists is largely a result of the insecurity experienced in this region due to the violence. Regarding the profile of foreign tourists to Acapulco, Canada, with 54.8%, is the country that contributes the largest number of tourists, followed by the United States with 30.32%, Cuba with 6.1%, Argentina with 4.2%, France with 2.2%, Guatemala with 0.64% and tourists from countries such as: Switzerland, Philippines, Estonia, Colombia and Bulgaria, resulting in a sample of 0.32% each. In Table 2, we can see the totals arrivals of tourists in Acapulco.

Table 2.

Total tourist arrivals to Acapulco.

Although Acapulco is considered a scarcely sustainable tourist destination that has an overexploitation of its natural and landscape resources, in recent years, it has been working to try to reverse this situation. To this end, it has been integrated into initiatives related to innovation, technology, universal access and sustainability that is reflected as part of its vision to be achieved in the coming years, at the local level in the Municipal Development Plan 2015–2018, and aligned with State Development Plans (2016–2021) and National Development Plans (2013–2018). More recently, Acapulco approved the “Municipal Development Plan 2018–2021” which is aligned with the “2018–2024 Nation Project” and the “2016–2021 State Development Plan” and the sustainable development objectives.

The State Society for the Management of Innovation and Tourism Technologies (SEGITTUR), attached to the Ministry of Industry, Energy and Tourism, reporting to the National Department of Tourism, and responsible for promoting innovation (R + D + i) in the Spanish tourism industry, defines a Smart Tourism Destination (STD) as “an innovative tourism destination, consolidated by means of a cutting-edge technological infrastructure, assuring the sustainable development of tourism territories, accessible to everyone, simplifying [a] visitor’s interaction and integration with the environment, while enhancing the quality of the experience at [the] destination and improving [the] inhabitant’s quality of life.” ([124], p. 13). In the case of Acapulco, sustainability is one of the factors considered and one of the objectives to be achieved in the coming years, and even though for some authors such as Aguilar-Torreblanca, Hernández-Lobato and Solis-Radilla [125], the process is at an initial stage and this evidence is still not clearly perceived, the path to be followed does seem to be clear. Therefore, the choice of Acapulco seems appropriate for the purposes of this study.

The objective of the study was not to find clients looking for sustainability, but the perceptions that they have on the sustainability of the destination, and how it influences the expectations about it.

4. Data Analysis

The study of the data used structural equation models that were estimated from the matrices of variances and covariances by the maximum likelihood procedure with EQS 6.4 statistical software [126]. First, we carried out a study of the dimensionality, reliability and validity of the sustainability scale to ensure that we were measuring the construct that it was intended to measure. This analysis also permitted us to refine the scale, eliminating non-significant items [127,128]. The final number of items was 13 (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Analysis of the dimensionality, reliability and validity of the scale of tourist destination sustainability.

In the case of sustainability, the items sharing the same dimension were averaged to form composite measures [129,130,131]. Composite measures of sustainability are combinations of items to create score aggregates that are then subjected to confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) together with the rest of the scales considered in the study, in order to validate them. In CFAs, the use of composite measures is useful for two reasons. First, it enables us to better meet the normal-distribution assumption of maximum likelihood estimation. Second, it results in more parsimonious models as it reduces the number of variances and covariances to be estimated, thus increasing the stability of the parameter estimates, improving the variable-to-sample-size ratio and reducing the impact of sampling error on the estimation process [129,132,133,134,135]. Thus, a composite measure for each dimension of sustainability was introduced as an indicator variable in the analyses conducted to assess the dimensionality, reliability and validity of the scales, and subsequently, the invariance of the instrument of measurement.

Table 4 shows the discriminant validity of the dimensions of tourist destination sustainability, evaluated through average variance extracted (AVE) [136]. This means a construct must share more variance with its indicators than with other constructs of the model. This occurs when the square root of the AVE among each pair of factors is higher than the estimated correlation among those factors; as occurs here, thus ratifying its discriminant validity.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity of the scales associated with tourist destination sustainability.

Below the diagonal in the Table 4, we can see the correlation estimated among the factors, and in the diagonal, the square root of Average Variance Extracted (AVE).

Subsequently, following Bandalos and Finney [129], Bou-Llusar et al. [130] and Landis et al. [131], once composite measures were formed from the items sharing the same dimension in the tourist destination sustainability scale, we analysed the psychometrical properties of the scales forming the model. As can be observed in Table 5, the probability associated with chi-squared reached a value higher than 0.05 (0.18179), indicating a good overall fit of the scale [137]. Convergent validity was demonstrated on the one hand because the factor loadings were significant and higher than 0.5 [135,138,139,140] and, on the other hand, because the average variance extracted (AVE) for each of the factors was higher than 0.5 [136]. As for the reliability of the scale, the indices of composite reliability of each of the dimensions obtained were higher than 0.6 [135].

Table 5.

Analysis of the dimensionality, reliability and validity of the measurement scales.

Table 6 shows the discriminant validity of the construct considered, since the square root of the AVE among each pair of factors was higher than the correlation estimated among the factors, thus ratifying its discriminant validity [136,141].

Table 6.

Discriminant validity of the scales associated with the model.

In the below the diagonal we can see the correlation estimated among the factors, and in the diagonal the square root of AVE.

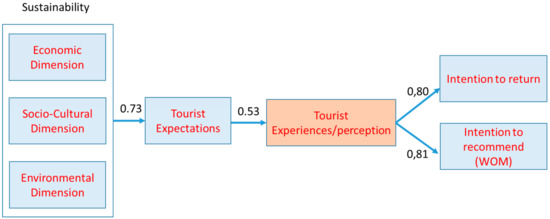

To test hypotheses 1 to 4, we next performed an analysis of the causal relationships (Table 7). This was adequate because the probability of the chi-squared was higher than 0.05 (0.11078), CFI (0.992) and NNFI (0.987) were close to unity and RMSEA was close to zero (0.022). The result of the analysis showed that the four relationships posited in the model were supported. Thus, sustainability is an antecedent of expectation (H1). Experience is determined by expectation (H2). Finally, experience determines both intention to return (H3) and WOM (H4).

Table 7.

Structural model relationships obtained.

To the extent that the study focused on hypotheses based on causal relationships, the level of interest in sustainability was not a relevant fact for the study, but what was interesting to see were the relationships among the variables.

To the extent that all the causal relationships from sustainability to the intentions to return were significant, it can be concluded that sustainability had a significant indirect effect on the intentions to return and on the intentions to recommend—in both cases the value of this effect was 0.31.

Sustainability was an antecedent of expectations (0.73), with an explained variance of expectations of 71%. Expectations, on the other hand, were an antecedent of perceptions/experience (0.53), with an explained variance of perceptions/experience (0.46). As for the perceptions/experience, they were an antecedent of the intentions to return (0.80), the variance being explained by the intentions to return from 0.64. Finally, perceptions/experience were an antecedent of the intentions of recommending (WOM) (0.81), the variance being explained by the intentions to recommend (0.65).

The model to be tested presents a very good fit and, in addition, the standardized factorial loads were high and all statistically significant (t-value > 1.96) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Results of the structural model.

5. Discussion

The sustainability of tourist destinations is a key factor for success and development both in the present and in the future [140]. Despite the growing importance of tourism due to its contribution to the economies of many countries and the global economy, and also as a research field in recent decades, in the analysis of tourism sustainability (and especially its measurement) there is still no consensus about the methodology to use for its measurement [116]. Sustainability has been acquiring a crucial ever-increasing role in recent years from the supply point of view (which includes the public and private sectors), the residents of the destination and demand by tourists.

The definition of a Smart Tourism Destination (STD) integrates sustainability as one of its four basic pillars, together with innovation, technology and universal accessibility and, therefore, its contemplation and development is fundamental for any destination [125]. Thus, it is important that local authorities continue to work on its consideration, implementation and the improvement of the destination as fundamental success factors. We must not forget that smart tourist destinations are aimed at increasing their competitiveness and improving the tourist experience, so it is very important to know how to manage resources, develop them properly and transmit them in the best possible way from this eclectic perspective and with a wider time horizon.

Acapulco is a mature sun and beach destination that needs to be renewed and revitalized in several ways, and thus able to return to its previous reputation as a renowned interesting and attractive tourist destination for international tourists. A commitment to sustainability is fundamental and necessary, and the path Acapulco has already started in that direction should lead to a successful conclusion. The economic and environmental dimensions are crucial because of the aforementioned motives, where the renewal and economic development of the destination must be combined with the preservation of the natural and landscape resources of the environment.

The sensitivity shown by tourists in general has also been growing in recent years, and therefore has become an important factor in their final decision process. Along with sustainability, the need to live unique and memorable experiences by tourists who visit them has also gained prominence over time, supported by ICT and by the need for tourists to share their travel experiences. Therefore, the change in orientation towards a tourism strategy focused on experience provides opportunities for tourism companies. In addition, the accumulated knowledge of interaction with tourists can be incorporated into intelligence. This intelligence is specific to the destination and is user oriented, thus providing a source of intangible competitive advantage, and is therefore more difficult to imitate or copy. In this sense, the interrelation with residents and their involvement in the generation of experiences is a key success factor [140,142].

The generation of expectations is based on several factors, such as the experiences of other tourists that are shared in digital environments, the values, beliefs and culture of tourists, the consideration of a sustainable destination, etc. In our case, for international tourists who visit Acapulco, the generation of expectations is based on finding a non-contaminated environment, being able to visit the most emblematic and historical places and being able to meet some famous person with whom to interact and to take photos.

On the other hand, the experiences lived in the destination can help tourists get away from their daily routines. Besides, the international tourists interviewed showed a high loyalty to the destination and in the intentions of recommending them to their family and social environments, so it is essential to continue working along the indicated line.

In our research, international tourists create their own experiences based on the attractiveness and the different activities that they carry out in the destination, generating their own content, allowing them to disconnect from their daily routines in the places where they usually work and live, as reflected in previous studies by other authors [57,121].

In our case, the research conducted has confirmed the four hypotheses proposed in this study. Therefore, sustainability significantly influenced the generation of expectations by tourists, and this in turn influenced the way in which experiences were generated in the destination. The experiences on their part also influenced the generation of WOM of the destination, its recommendation and the behaviour of the tourist in the future with a renewed desire to return to the destination. From this perspective, the proposed model and the relationships among its variables were fulfilled in its entirety. These relationships included the influence of experiences on the intentions to recommend (WOM) (0.81) and the intention to return to the destination (0.80), which confirmed the need for companies and local authorities to jointly follow the principle of tourism governance, being able to create the best possible experiences based on the tourist intelligence that the collected data and the information generated by tourists that their traveller journey map should offer them. The way in which expectations are handled regarding the destination and the way in which the content is managed in the different media and communications support is a relevant factor that can help tourists to have a more or less real vision of the destination. Also, for companies, tourists and public bodies, understanding these expectations helps to better generate experiences that are appropriate to the level of knowledge of the tourists who visit them. These memorable experiences must exceed expectations and delight tourists [143]. The integration and participation of residents in the generation of memorable experiences has also become a fundamental factor of success, as shown by some studies [140], so their motivation and involvement will be fundamental, as well as their prospects for future benefits and how they influence the sustainability of the destination, as previous scholars have suggested [144].

In short, this research has allowed to corroborate the importance of sustainability in the generation of expectations of a tourist destination, in the way, a priori, tourists can generate their expectations and how these expectations, in turn, influence the experiences lived, and as a consequence, in their future behaviour, both in their intentions to return and in their recommendations to their family and social environments. From this perspective, destinations can be considered as a macroproduct that provides complex integrated experiences with services, facilities and offers made available to visitors to meet their needs at the destination [145], which may also be a concept of perception, interpreted subjectively by consumers according to their travel itinerary, cultural and educational background, objectives for visiting and past experience [75]. All these aspects are reflected in our study, which corroborates the hypotheses set out in the abovementioned sense, and which encourage public and private agents to be involved in its management.

The uniqueness of this research lies in the linking of the necessity of knowledge and understanding of the tourist’s behaviour and the factors influencing loyalty towards the destination, with the sustainable tourism principles.

6. Recommendations for Management, Future Lines of Research and Limitations

Public and private companies in Acapulco must continue working to improve their image. Good tourism governance is fundamental to the success of this task. To do this they must continue investing in sustainability and thereby improve the expectations of tourists and visitors. From a practical point of view, the findings of this study can be used by destinations managers and tourism service providers in Acapulco to invest, from a sustainability point of view, in creating memorable experiences in the destination, relying on those aspects that are most relevant in terms of existing tourism resources and products, such as improve the non-contaminated environment and the most emblematic and historical places which are visited by tourists. It is important that they encourage the participation of residents in a natural and credible way, so that they facilitate the integration and participation of tourists and visitors in the most emblematic activities that may interest them, and that help to create unique memorable experiences. In order to reverse the image of a non-sustainable destination, tourism must be involved in the sustainable practices that are carried out and seek behaviour more in line with this objective, as pointed out by some authors such as Pulido-Fernández and López Sánchez [81], among others.

It is very important to integrate tourists in local customs which display good habits of sustainable behaviour that make Acapulco a pleasant and desirable destination for all those who visit them. The research findings contribute to broadening the current theory about loyalty in destination and show the connection between sustainability–expectations–experiences–revisit and recommend. Therefore, this study can help public and private managers in Acapulco to mark the future path towards what they have to address in order to be an attractive, desirable and sustainable destination.

Regarding the limitations of the study, the characteristics of the destination may condition the answers, so it is necessary to replicate the model proposed in other more sustainable destinations from the perspective of the visiting tourist. The type (sample of convenience) and size of the sample, foreign tourists which are a minority compared to domestic ones, can condition the answers and, therefore, we could look for a larger sample that is a reflection of the destination and that allows to generalize the obtained results. This is a study that allows increasing knowledge about the process of obtaining the loyalty of tourists, based on the knowledge of their intentions of return and recommendation of the destination. In addition, the time of year can condition the profile of the sample, so it would be advisable to develop the study design and data collection for different times of the year, looking for a more longitudinal study. The proposed model could also be completed with the inclusion of other variables such as the image and reputation of the destination, tourist satisfaction, or even residents’ own attitude in the generation of experiences. This could result in wider results that help to make better decisions on the part of the authorities in the destination.

Regarding future lines of research, we must continue to investigate the sustainability of tourism. For example, we could adapt the model in Reference [146] to this destination or to any other sun and beach destination which has developed initiatives to become a sustainable destination. We also believe that it may be interesting to adopt Mihalic’s [41] point of view and attempt to determine if, in responsible tourism (for example, in the form of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), there are only practices that seek to conceal an economic interest—that is, recognizing the need to become more ecological, but at the same time, protecting the values of the economic pillar. Therefore, it is necessary to continue investigating in order to discern and evaluate whether the green movement mentioned above, determined by the capitalist system, is in fact leading towards a sufficiently sustainable future. It is also important to continue advancing the social dimension of sustainability, which, as we have seen in this work, is possibly the least developed of the dimensions.

Author Contributions

All authors collaborated equally. Conceptualization, M.M.S-R, L.H-L and L.J.C-F.; Data curation, L.J.C.F.,L.H-L and H.T.P.-D.; Formal analysis, L.J.C-F; Investigation, M.M.S-R, L.H-L., L.J.C-F. and H.T.P.-D.; Methodology, M.M.S-R, L.H-L., L.J.C-F. and H.T.P.-D; Project administration, M.M.S-R, L.H-L.; Supervision, M.M.S-R, L.H-L., L.J.C-F. and H.T.P.-D; Writing—original draft, L.J.C-F.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). Indicators of Sustainable Development for Tourism Destinations: A Guidebook; ESP: Madrid, Spain, 2004; ISBN 92-844-0726-5. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Delgado, A.; López-Palomeque, F. Measuring sustainable tourism at the municipal level. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 49, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. Sustainable Tourism development: A Critique. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Delgado, A.; López-Palomeque, F. The growth and spread of the concept of sustainable tourism: The contribution of institutional initiatives to tourism policy. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Amaranggana, A. Smart Tourism Destinations. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2014; Xiang, Z., Tussyadiah, L., Eds.; Springer: Dublin, Ireland, 2014; pp. 553–564. [Google Scholar]

- Gretzel, U.; Werthner, H.; Koo, C.; Lamsfus, C. Conceptual foundations for understanding smart tourism ecosystems. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 50, 558–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Higham, J.; Lane, B.; Miller, G. Twenty-Five Years of Sustainable Tourism and the Journal of Sustainable Tourism: Looking Back and Moving Forward. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J.A. La sostenibilidad en el sector Turístico: Del marco ambiental global Al marco económico-social local. Desarro. Local Sosten. 2013, 16, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Boley, B.B.; McGehee, N.G.; Hammett, A.L. Importance-performance analysis (IPA) of sustainable tourism initiatives: The resident perspective. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boes, K.; Buhalis, D.; Inversini, A. Smart tourism destinations: Ecosystems for tourism destination competitiveness. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2016, 2, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos, A.; Mertens, F. Os desafios do turismo no contexto da sustentabilidade: As contribuições do turismo de base comunitária. PASOS. Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural 2015, 13, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. Sustainable tourism: An evolving global approach? J. Sustain. Tour. 1993, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolfani, S.H.; Sedaghat, M.; Maknoon, R.; Zavadskas, E.K. Sustainable tourism: A comprehensive literature review on frameworks and applications. Ekonomska Istraživanja/Econ. Res. 2015, 28, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, B. Will sustainable tourism research be sustainable in the future? An opinion Piece. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalic, T. Sustainable-responsible tourism discourse—Towards ‘responsustable’ tourism. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 111, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. (Eds.) Tourism Collaboration and Partnerships: Politics, Practice and Sustainability; Channel View Publications: Clevedon, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. The “critical turn” and its implications for sustainable tourism research”. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorf, J. Les Dévoreurs de Paysages. Le Tourisme Doit-il Detruire les Sites qui le Font Vivre? 24 Heures: Lausanne, Switzerland, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorf, J. Towards new tourism policies—The importance of environmental and sociocultural factors. Tour. Manag. 1982, 3, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorf, J. The Holiday Makers: Understanding the Impact of Leisure and Travel; Heinemann: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorf, J.; Zimmer, P.; Glauber, H. Für einen andern Tourismus (towards an Alternative Tourism); Taschenbuch Verlag Frankfurt am Main: Fischer, Germany, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Woodside, A.G.; Caldwell, M.L.; Miller, N.D. A Broadening the Study of Tourism. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2004, 17, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, D.L.; Randers, J.; Behrens, W.W., III. The Limits to Growth; Potomac Associates Book-niverse Books: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- WCED. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Briguglio, L.; Archer, B.; Jafari, J.; Wall, G. Sustainable Tourism in Islands and Small States: Issues and Policies; Pinter: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R.W. Tourism, environment, and sustainable development. Environ. Conserv. 1991, 18, 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. Sustainable tourism: A state-of the-art review. Tour. Geogr. 1999, 1, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellas, F.; Becherel, L. The International Marketing of Travel and Tourism: A Strategic Approach; MacMillan: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpley, R. Tourism and sustainable development: Exploring the theoretical divide. J. Sustain. Tour. 2000, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagosa, F.; Priestley, G.K.; Llurdés, J.C. El turismo en el marco de una estrategia de planificación sostenible general en Cataluña. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles 2011, 57, 267–293. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez-Gómez, J.A.; González-Gómez, T. Analysing stakeholders’ perceptions of golf-course-based tourism: A proposal for developing sustainable tourism projects. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapera, I. Sustainable tourism development efforts by local governments in Poland. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 40, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J. A Framework of Approaches to Sustainable Tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 1997, 5, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B. Theoretical activity in sustainable tourism research. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 54, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, J. Perception of small tourism enterprises in Lao PDR regarding social sustainability under the influence of social network. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowforth, A.; Munt, I. Tourism & Sustainability: New Tourism in the Third World; Psychology Press: London, UK, 1998; ISBN 0415137640/9780415137645. [Google Scholar]

- Tanguay, G.A.; Rajaonson, J.; Therrien, M.-C. Sustainable Tourism Indicators: Selection Criteria for Policy Implementation and Scientific Recognition. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 21, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmelash, A.G.; Kumar, S. Assessing progress of tourism sustainability: Developing and validating sustainability indicators. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S.; Page, S.J. Destination Marketing Organizations and destination marketing: A narrative analysis of the literature. Tour. Manag. 2014, 41, 202–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, A.; Beeton, R.J.S.; Pearson, L. Sustainable Tourism: An Overview of the Concept and its Position in Relation to Conceptualisations of Tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2002, 10, 475–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simão, J.N.; Partidário, M.-D.R. How does tourism planning contribute to sustainable development? Sustain. Dev. 2012, 20, 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatori, A.; Smith, M.K.; Puczko, L. Experience-involvement, memorability and authenticity: The service provider’s effect on tourist experience. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uriely, N. The Tourist Experience: Conceptual Developments. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boorstin, D.J. The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America; Harper: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Clawson, M. Land and Water for Recreation: Opportunities, Problems and Policies; Rand McNally: Chicago, IL, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Clawson, M.; Knetsch, J.L. Economics of Outdoor Recreation; The Johns Hopkins Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- MacCannell, D. The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class; Schocken Books: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, L.; Ash, J. The Golden Hordes: International Tourism and the Pleasure Periphery; Constable Ltd.: London, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, E. A phenomenology of tourist experiences. Sociology 1979, 3, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. The Sociology of Tourism: Approaches, Issues, and Findings. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 1984, 10, 373–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Traditions in the qualitative sociology of tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1988, 15, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Femenia-Serra, F.; Neuhofer, B. Smart tourism experiences: Conceptualisation, key dimensions and research agenda. Investig. Reg. J. Reg. Res. 2018, 42, 129–150. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, J.H.; Dierking, L.D. The Museum Experience; Whalesback Books: Washington, DC, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, J.B.; Gilmore, G.H. Welcome to the experience economy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy; Harvard Business School: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Stamboulis, Y.; Skayannis, P. Innovation strategies and technology for experience-based tourism. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Fiore, A.M.; Jeoung, M. Measuring Experience Economy Concepts: Tourism Applications. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Rahman, I. Cultural tourism: An analysis of engagement, cultural contact, memorable tourism experience and destination loyalty. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 26, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. The Future of Competition: Co-Creating Unique Value with Customers; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Neuhofer, B.; Buhalis, D.; Ladkin, A. Conceptualising technology enhanced destination experiences. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2012, 1, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binkhorst, E.; Dekker, T.D. Agenda for co-creation tourism experience research. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2009, 18, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, V.W.S.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Exploring the essence of memorable tourism experiences. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 1367–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Jacinto, L.; Martin-Garcia, J.S.; Bertiche-Haud’Huyze, C. A model of tourism experience and attitude change. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 1024–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalan, R.; Narayan, B. Improving customer experience in tourism: A framework for stakeholder collaboration. Socio Econ. Plan. Sci. 2010, 44, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, J.E.; Ritchie, J.R.B. The service experience in tourism. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.; Xu, F. Student Travel Experiences: Memories and Dreams. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2009, 18, 216–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urry, J. The Tourist Gaze, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dann, G.; Jacobsen, K.S. Tourism smellscapes. Tour. Geogr. 2003, 5, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meacci, L.; Liberatore, G. A senses-based model for the experiential tourism. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2018, 14, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Ritchie, J.R.B.; McCormick, B. Development of a scale to measure memorable tourism experiences. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Cross-cultural validation of a memorable tourism experience scale (MTES). J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandralal, L.; Valenzuela, F.-R. Exploring memorable tourism experiences: Antecedents and behavioural outcomes. J. Econ. Bus. Manag. 2013, 1, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoch, S.J.; Deighton, J. Managing what consumers learn from experience. J. Mark. 1989, 53, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H. Determining the factors affecting the memorable nature of travel experiences. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2010, 27, 780–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D. Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, P.; Fonta, X.; Scarlesa, C.; Weedenb, C.; Harrisona, C. Tourist destination marketing: From sustainability myopia to memorable experiences. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2014, 9, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjelstul, J. Vehicle electrification: On the ‘green’ road to destination sustainability. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2014, 3, 137–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyall, A.; Garrod, B.; Wang, Y. Destination collaboration: A critical review of theoretical approaches to a multi-dimensional phenomenon. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2012, 1, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, H. Responsible Tourism and the Market; Occasional Paper 4; International Centre for Responsible Tourism: Dublin, Ireland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.P.S.; Chancellor, H.C.; Cole, S.T. Measuring residents’ attitudes toward sustainable tourism: A reexamination of the sustainable tourism attitude scale. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Fernández, J.I.; López-Sánchez, Y. Perception of Sustainability of a Tourism Destination: Analysis from Tourist Expectations. Int. Bus. Econ. Res. J. 2014, 13, 1587–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cetin, G.; Dincer, F.I. Influence of customer experience on loyalty and word-of-mouth in hospitality operations. Anatolia 2014, 25, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H. The antecedents of memorable tourism experiences: The development of a scale to measure the destination attributes associated with memorable experiences. Tour. Manag. 2014, 44, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dell, T. Tourist Experiences and Academic Junctures. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2007, 7, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Jamal, T. Conceptualizing the creative tourist class: Technology, mobility, and tourism experiences. Tour. Anal. 2009, 14, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]