1. Introduction

The Creating Shared Value (CSV) strategy [

1] that emerged from the Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) business model can be summarized as "Joint Pursuit of Corporate Value and Social Value" [

2]. Management academia and corporations are taking efforts to resolve social problems and investigate sustainable business models. In the course of these efforts, there are increasing numbers of local and global companies that have successfully achieved common prosperity through CSV models. In the CSV strategy, government agencies are defined as subjects to lead CSV with corporations. The roles of the government are to provide institutional support and cooperative partnership with corporations and civil society, establish and support of legal infrastructure for companies, and evaluate and advice on CSV activities by enterprises [

3].

Meanwhile, with the reflection on the New Public Management (NPM) policy, which has been established as the representative public management strategy since the 1980s, administrative academics are actively pursuing exploratory researches centered on Public Values in order to establish a new paradigm to replace NPM. Public Value Movement [

4], Public Value Approach [

5], Public Value Management [

6], and Public Value Pragmatism [

7] are representative research products that appeared in this context. Wood [

8], who advocated Creating Public Value (CPV) for the first time, asserted that the nature of CSR policies should not be evaluated as the activities of the companies themselves, but as the policy of the government to carry out social responsibilities for the enterprises. Based on his opinion, Hwang [

9] insisted on that, "CSR is a policy to fulfill social responsibilities in the nature of quasi-public goods, so it falls under the responsibility of the government which is responsible for managing the social sector."

Internationally, the United Nations Global Compact, in 2000 and 2007, has already recommended that enterprises, as well as government organizations and all public agencies, should be responsible for socially responsible actions [

10,

11]. ISO 26000 officially adopted the term SR (Social Responsibility) and emphasized the need for all organizations, including governments, to behave socially and responsibly and set out comprehensive international standards guidelines [

12]. In this regard, government agencies and other public organizations seem to seek new roles and functions through shared value creation along with corporations, beyond the traditional roles of corporate supporters or regulators [

9].

However, while private companies are striving to create social values that do not hold any intrinsic value, public organizations have established for the public interests often evaluated as passive in solving social problems [

13,

14,

15]. Recently, the interests of the domestic and foreign academic circles in creating social values surrounding public organizations have spread rapidly to the recommendations of practical goals by international organizations [

16]. Furthermore, increasing demands for the practice of social values have taken the lead by civil societies [

17,

18], along with the attempt by political circles to legislate [

19].

The purpose of this study is to identify CSV strategies that fits the purposes and characteristics of public organizations who offer military service like KACMS (Korea Army Cadet Military School) because KACMS [

20], the country’s largest military training institute that trains 93% of The Republic of Korea Army (ROKA) officers, is also recognized as one of the institutions that experiences strong core competitiveness through CSV strategies while addressing social, environmental, and economic issues in its region [

21]. In other words, the research is conducted in order to identify how public organizations can enhance their core competitiveness by using CSV strategies. In this study, we analyzed the CSV strategies, processes, and performances that KACMS carried out spanning the period of 2017-2018. The CSV cases collected through the study are presented using the CSV framework 1.0 developed by the IIPS (Institute for Industrial Policy Studies) for logical understanding.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 explores previous literature review on main contents of CSV, the expected effects and criticisms analyzed from the theoretical and practical points of view.

Section 3 describes research method used in this study. In

Section 4, we analyze KACMS’ CSV strategy, focusing on subject, environment, resources, mechanism, and performance elements. In

Section 5, covers discussion and explains the findings, implications, and limitations of the research. In

Section 6, we conclude this research, thereby providing new insights into the future for public military institutions in achieving CSV strategies.

2. Previous Literature Review

The strategic CSR is not a concept of cost but a source of opportunities, innovations, and competitive advantages that helps corporates improve their competitive advantages while contributing to society [

13,

22]. This concept has evolved into the concept of Creating Shared Value (CSV), in which the improvement of competitive advantages and social contributions create economic values and social values at the same time by linking mutually rather than achieving independently [

1]. Creating Shared Value, which can be summarized as Joint Pursuit of Corporate Values and Social Values, is a concept emerging from a continuous line of Corporate Social Responsibility [

2]. At the beginning, CSR started with the charitable and philanthropic personality centered on the leader or CEO of the company, but recently its scope and roles have been expanded with the growth of corporate citizenship [

3]. CSR is classified into four stages according to its purposes: corporate retention, corporate satisfaction, corporate image and corporate competitiveness [

3]. The ultimate goal of corporates’ CSV strategies is to increase their competitiveness through social value creation activities.

Despite the theoretical developments and practical contributions made so far, the results of researches on the relationship between CSR performances and corporate values have varied from ‘negative relations’ to ‘irrelevant’ [

23].

According to the positive opinions of CSR, it positively affects corporate credibility and management performances and reputations [

14,

15], and can be used as a method to enhance satisfactions with various stakeholders [

16]. CSR activities contribute to solving social imbalances and environmental problems while enhancing corporate performances [

17,

18,

19], increasing employee satisfactions with work, and affecting their turnover rates positively [

24]. CSR not only raises employees’ self-esteem, but also bolster the image of both the companies and its employees, thereby enhancing work performances [

25]. In the case of Korean companies, CSR can reduce labor disputes and the costs of solving problems by improving the trust relationships with employees [

8] and promoting employees’ commitments to the organizations [

26]. In practice, Korean companies pursuing CSR have been found to have increased both accounting profitability and marketability [

27]. Companies that have achieved social responsibility performances more effectively have shown better Corporate Financial Performances (CFPs) than those that do not [

28].

Looking at the negative stances on CSR, Leavitt [

29] and Friedman [

30] argue that social responsibility activities such as philanthropy and donations that are not related to business accrue unnecessary expenses, thereby hindering the company’s unique values, profit creations and maximizations of shareholder values. In addition, Friedman [

31] emphasized that CSR is helpful to manage the reputations of the entrepreneur but not to manage the economic performances of the company. Crane et al. [

32] argued that CSV is not quite different from the existing strategic CSR, and that the social goals achieved through CSV and the economic goals of the companies are incompatible. In addition to this criticism, Shared Value is not a new concept but a term that has already been widely used in various disciplines [

32]. Although CSV is a type of strategic CSR, if CSV is over emphasized, there are potential risks of criticism that one can possibly use social values to pursue its strategic and economic interests [

32]. Furthermore, CSR is just a window-dressing of companies packaged under the name of ‘social responsibility’ [

33] and is nothing more than a watchdog of multinational corporations in preparation for government regulations [

34].

The reasons for the differences between CSR evaluations are that the degree of specificity is still insufficient, and it can be attributed to inherent problems in measurement variables and measurement methods [

35]. However, the correlation between CSR and corporate value enhancements has been analyzed to be more positive than negative.

In Korea, discussions about CSR initiated by corporations are gradually spreading over the public sector [

10]. Public institutions are being asked to contribute to Balanced Development for the Sustainable Society in addition to their existing economic and policy roles, as the size and influence of the domestic economy are gradually increasing [

10]. Furthermore, it is emphasized that the government should play a role in CSR implementation according to the claim that CSR is based on cooperative relations with government, business and civil society [

36,

37]. Accordingly, the UNGC (UN Global Compact) Korea Association, which was established in 2007, supports 258 members companies that joined by March 2019 to faithfully fulfill the Ten Principles of the Association [

38]. The domestic political parties are also striving to enact the Three Laws related to social economy [

39], and judicial organizations are calling for the legal systems to support them [

40].

The Safety Culture, which was first used in the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear accident report, is defined as the values, attitudes, perceptions, competencies, and behaviors of individuals and groups that determine the commitments, forms and efficiencies of their organization’s safety and health management issues [

41]. However, Zohar analyzed the validities of the eight factors that make up the organizational safety climates and proved that the level of management’s perceptions of safety and education training are the most important [

42]. In addition, he found that safety culture consists of managerial values, safety communications, safety educations and safety equipment, and is mediated through knowledge and motivations, which directly affects safety compliance activities [

43].

Under these backgrounds, the efforts have been actively made to incorporate safety culture into business management. Fleming and Lardner [

44] asserted that the safety culture begins at a dependent stage and goes through an independent stage, eventually leading to an interdependent stage, according to safety maturity. In particular, they emphasized that when the organization is at an interdependent stage, the authority on safety issues is delegated to the team, and the organization is at the level of CSR, which promotes its inherent values while also taking into consideration the safety of its stakeholders.

3. Methodology and the Framework for the Case Analysis

Case-based research has been widely used to develop new insights and understand complex areas of management practice, thereby contributing to the advancement of theory [

45]. ‘How’ question as a research question are more explanatory and likely to lead to the use of a case study [

46]. The case research method is both appropriate and essential where either theory does not yet exist or is unlikely to apply, where theory exists but the environmental context is different or where cause and effect are in doubt or involve time lags. Case studies also provide an excellent vehicle for other research roles such as developing understanding, a role that may have particular significance in a field where the subject matter is very complex [

47].

Up to now, the majority of CSV studies conducted so far focus on only corporations and their contents are mainly covered to identify the correlation between the independent variables and financial or non-financial performance from a business perspective. However, this study explores CSV strategies for public military institution like KACMS so case-based research method will be proper and has been applied to understand complex aspects of CSV practice in public sector. The reason why the paper is based on a single case study is that finding out the case for public military institution related to CSV strategy may be very difficult. The time-span required for the analysis began in April 2017, when KACMS began to envision the CSV strategy, and finished in December 2018, when the initial performance of the strategy could be assessed.

In the meantime, document analysis is a systematic procedure for reviewing or evaluating documents. Like other analytical methods in qualitative research, document analysis requires that data be examined and interpreted in order to elicit meaning, gain understanding, and develop empirical knowledge [

48]. This study has been also used document analysis so documents that may be used for systematic evaluation as part of a case study take a variety of forms. They include agendas, attendance registers and minutes of meetings, brochures, homepage on the internet, press releases, official documents issued by local governments, survey of Korea Institute for Defense Analyzes (KIDA), internal documents and medical records of KACMS and in-depth interviews with commanders and cadets.

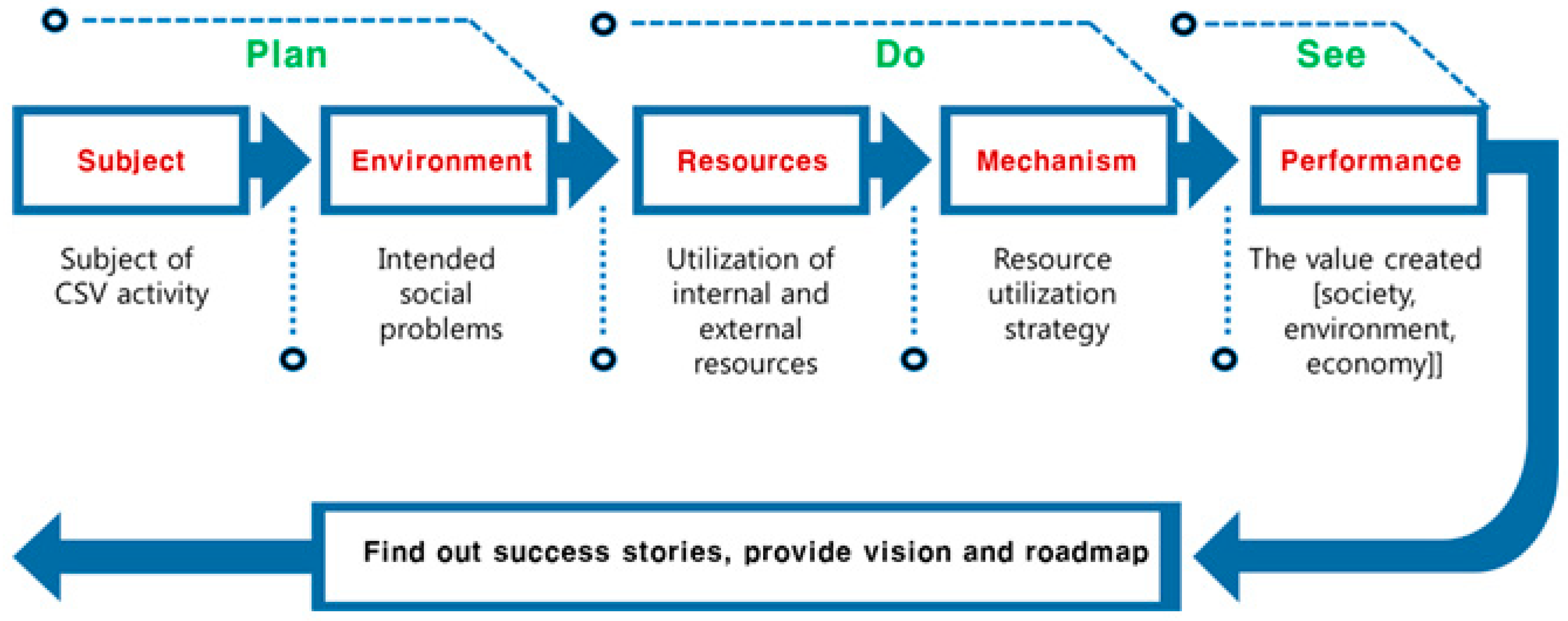

As shown in

Figure 1, the framework of the analysis used in this case study was adjusted by the researcher to explain the findings more logically based on the CSV framework 1.0 developed by IIPS [

49] combining the PDS (Plan-Do-See) model with the SER-M model [

50].

4. CSV Strategy of Korea Army Cadet Military School

4.1. Subject; KACMS-Centric Early-Level Network Governance

One of the most important factors in determining the success of the CSV strategy is the subject that establishes and implements the strategy. The results can vary greatly depending on the backgrounds, purposes, and values of the subject, as well as the thinking and decision structure of the subject [

40]. In this regard, the stakeholder theory [

51,

52] is a valuable tool for identifying the subject and environment performing the CSV strategy. The achievement of the CSV strategy can be seen in the process of realizing social values by maximizing the different needs and expectations of various stakeholders while promoting their own values. It is crucial for the CSV strategy builder to secure legitimacy from internal and external stakeholders [

53,

54,

55]. According to the viewpoint ‘Who is leading the CSV strategy?’, the subjects of the CSV strategy can be classified into (1) corporate-led type, (2) social-driven type and (3) multilateral cooperation type [

56].

Stakeholders involved in the CSV activities of KACMS are; (1) Officer cadets and their relatives, (2) Officials of the universities to which the ROTCs belong (i.e., faculty members, alumni associations, sponsoring organizations), (3) Military organizations such as senior and adjoining units of KACMS, (4) Nonprofit organizations and alumni (i.e., alumni association, scholarship foundation, religious foundation, etc.), (5) Local governments and organizations (including the Goe-San County Agency [

2], the Goe-San County Council, the residents’ representatives and the local press, etc.). The CSV activities have been planned and implemented by KACMS, which is a government agency, under the circumstance in which various types of stakeholders seek their own organizational values and solve social problems. This type of CSV strategy can be viewed as a limited form of Cluster [

1] or Network Governance [

6] at an early level based on cooperative interactions and trusts between stakeholders.

4.2. Environment of KACMS for CSV Strategy

From the viewpoint of industrial organization theory [

57], the performance of the KACMS’ CSV strategy is determined when the subject correctly understands its environment and organically combines with internal and external resources. In order to understand the environment of the military school, the commandant of KACMS reaffirmed its installation and operation regulations, interviewed with their representatives, surveyed members, checked stakeholders’ complaints, and analyzed articles about stakeholders in order to identify the stakeholders’ needs and values.

The internal environmental factors of KACMS can be identified within the issues and social values pursued by stakeholders of this institution. The social values pursued by the agency are based on the organizational goals of the ROK Army [

58], which the organization belongs to. The goals of ROK Army include the Fostering of Elite Power Generation, and the Support for the Benefit of the People. The social values of KACMS, based on the organization’s purposes of establishment and the Army’s goals, are to firmly support "Competent Security and Robust Defense" by fostering elite officers. In addition, in order to support the National Benefit, it is necessary to grasp the needs of the residents of the Goe-san area, which is the reality of The People that this institution should support, and to solve their social problems. However, the social values of the officer cadets and their families are successful college graduates and their commission. Besides, the social values for Goe-san residents are to achieve balanced development in line with the government goal of Balanced Development of Regions, to develop a sustainable society by solving deepening community problems, and to succeed in the development of local traditions. Moreover, the social values pursued by more than 200 non-profit organizations consisting of officers, groups, alumni associations and university alumni association are continuous maintenance and developments of their officer groups in which talented individuals are enrolled in the programs that foster their own officers.

In Korea, the “Basic Act on the Status and Service of Soldiers” was enacted in 2015, and the newly launched central government emphasizes the safety of the people and the protection of the human rights of soldiers. The impact of these efforts of the legislature and the judiciary has increased the interests and expectations of military security and human rights for KACMS as well as for officer cadets and their families. Besides, in the political and social conflicts surrounding the solution of North Korea’s Nuclear Threat in 2017, the general public expected their leaders to protect the nation from the threats of the outside world and the nation in case of emergency. Additionally, as the new head of local government took office with the launch of the new central government, the residents of Goe-san County expected to resolve local issues, such as the common regional economic downturn, population decline and aging. Moreover, some of the scholars studying the defense policy asserted that the shortage of active duty resources due to the population cliff phenomena and the government’s shortening period of service could have a considerable influence on the officer acquisition system based on the Support System [

59].

4.3. Resources of KACMS for CSV Strategy

From the resource-based point of view [

60,

61], the CSV strategy of KACMS is determined by the internal and external resources possessed by the subject. The performance is determined by the ability to constantly acquire and accumulate such resources.

The internal core competencies [

62]; one of the most important internal core competencies to implement KACMS’ CSV strategy is the Commandant of the military school and the Commandant’s staff officers who support in practice with high loyalty and understanding his organizational management philosophy. Since the Commandant’s inauguration in April 2017, he has been seeking cooperation with local communities to ensure that KACMS is able to smoothly carry out its duties by meeting directly with stakeholders responsible for local administration, identifying and sharing relevant social issues. However, KACMS is carrying out its mission through student military education unit (ROTC) installed at 110 four-year universities nationwide. ROTCs have dual command structure under the direction of their university along with KACMS, so the units will be directly or indirectly influenced by the ideologies and operating methods of their university. However, for KACMS to mitigate the problem of span of control and to effectively command such special organizational characteristics and environments, there is no other choice but to delegate a considerable portion of the authority to 110 ROTC commanders (Colonels or Lt. Colonels). In the end, the CSV strategy of the institution is possible when the ROTC commanders who have been delegated the Commandant’s authority effectively combine the environments and resources of their college to operate creative and innovative mechanisms.

Furthermore, more than 8000 ROTC cadets are active in their universities throughout the country. They are excellent talents who have applied to the ROTC cadet course during the first and second years of college and have passed strict selection criteria set by the Ministry of National Defense including mental state, spirituality, personality, and physical strength in three stages. They are mostly young people in their early 20s, possessing a healthy body, strong physical strength, high public service motivation, organizational and cooperative skills, and familiarity with information technology. Additionally, the ROK Army utilizes the military’s core competencies to support national projects [

63]. Finally, the Army’s culture of concentrating its core competencies in order to promote national interests, and the abundant experience gained in the Army’s efforts to solve various social problems are the core competences that play important roles in quick recognition to efficiently resolve local social issues.

The external core competencies [

62]; KACMS does not normally have sufficient resources to solve all types of social problems that may appear in the region due to its organizational characteristics as a military educational institution. However, if it is determined that the agency should take the initiative to resolve any social problems within the region, the superior organizations of the institution will need to concentrate their command control and assets required through the cooperation of related military organizations. KACMS trains ROK Army executives through 11 specialized education programs, including officers, warrant officers, and the commanders of reserve forces. Officers commissioned through KACMS usually return to society after completing active duty for the mandatory period set by law, with the exception of some long-term officers. The number of officers returning to society has reached about 200,000 so far. They are naturally affiliated with non-profit organizations such as alumni groups of officers or alumni by commissioned year. These groups voluntarily contribute human and material resources to cadets of their officer’s group.

Besides, the ROK Armed Forces not only fulfilled its mission as the subject of national defense, but also played the role in the process of modernization and industrialization of the Republic of Korea [

59]. These proud history and traditions continue today, and there are young officers at the center of this transformation. The trust of the Korean people toward young officers has led to the expectation that they will play the leading roles in realizing the social values in various sectors of society after their retirement. This category of trust [

64] in the people includes confidence in the quality of KACMS’s CSV strategies and programs, as well as the reliabilities of the outcome.

4.4. Mechanisms of KACMS for CSV Strategy

From the mechanism-based perspective [

50,

65], the shared value-generating strategy is described as the mechanism that does not view each of the factors as an independent variable, but rather as the mechanism that uses or creates resources in response to environmental changes. These various types of mechanisms may appear both as the result of the strategy adopted by the subject and as the spontaneous phenomenon, but the naturally occurring mechanisms are sometimes controlled or adjusted by the CSV strategies. By applying Michael Porter’s value creation method [

6], KACMS has formed the Public Service Innovation Strategy and the Convergence Strategy with stakeholders and communities.

The Public Service (PS) Innovation Strategy has been promoted by the following three mechanisms with the emphasis on enhancing the performances of education and training, securing safety and guaranteeing human rights, which is the unique value of this institution.

4.4.1. PS Mechanism I

CSR and innovation are the foundation of business competencies [

66]. KACMS has tried to innovate the training programs. Approximately 8000 ROTC cadets nationwide have to be disciplined through their ROTC units installed at the universities during the semester, and ought to enter KACMS during the winter and summer vacation to receive the intensive military training for 12 weeks in total. The weather in Goe-san, where summer training is taking place (July to August) limits normal outdoor training with WGI (Wet-bulb Globe thermometer Index) of 29.5 or higher from 10:00 am to 4:00 pm. In order to settle this situation where the core values such as ‘intensive training’ and ‘safety assurance’ are in conflict, KACMS had chosen to adjust its training methods (i.e., switching to indoor training, replacing with demonstration training, and shortening training time). However, while these methods could relieve the occurrences of patients due to the heat waves, cadets had been provided with relatively low-quality training programs (i.e., lack of training time, shortage of practical training opportunities, and low tactical skills due to lecture-based training). These provisional measures had immensely undermined the generic values that military education institutions must pursue. On the other hand, about 8000 inhabitants of Goe-san town are active in the local economy due to the sudden population inflow of about 10,000 military man and cadets in this period, but the residents living in the apartments had experienced inconveniences when the capacity of the local waterworks facility had been exceeded, and some farmers had raised complaints about noise, dust, and crop damages caused by military training.

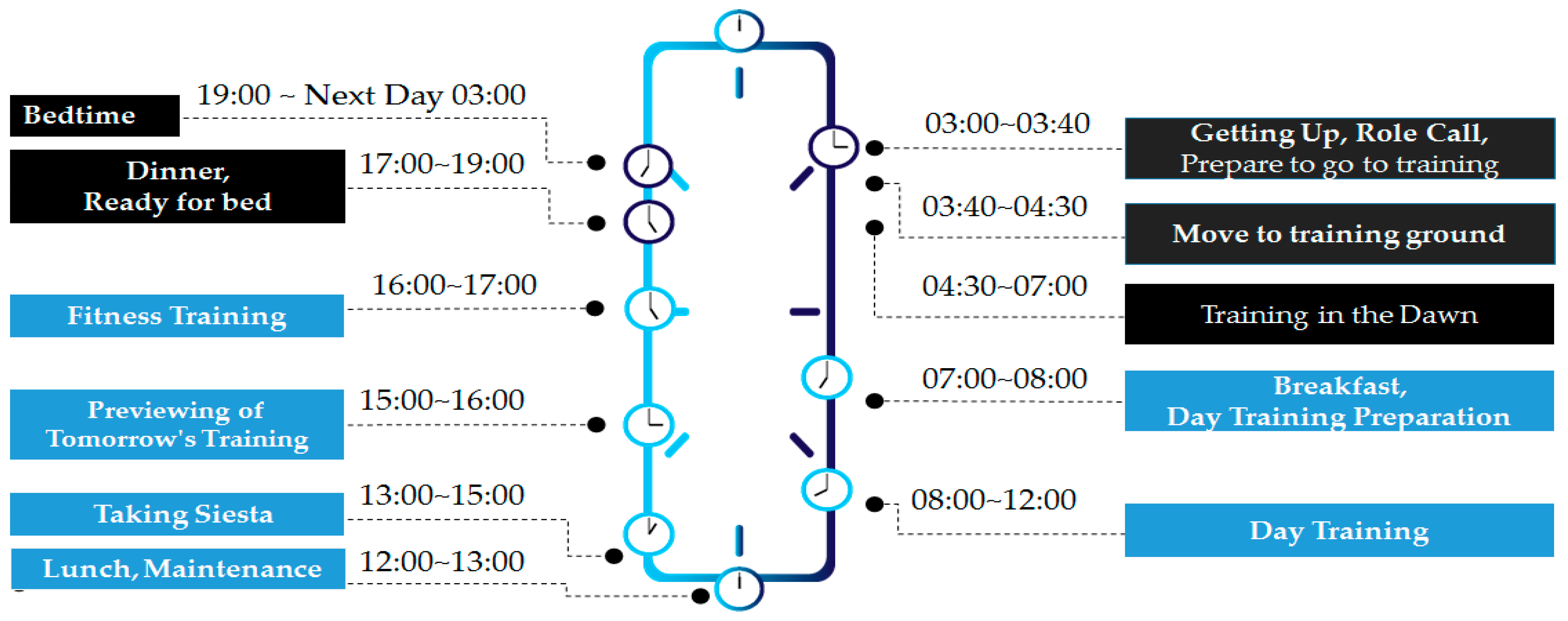

For resolving the complicated conflicts between its own values and social values, KACMS developed and applied the innovative mechanism summarized as ‘resting on a hot day and training on a cool night’. It combines the commandant’s philosophy of ‘strong training, sufficient rest’ and the principle of war of ‘saving and concentration’. The modified summer daily timetable had undergone an optimal adjustment by the analysis of weather conditions, training analysis data, and patient care records over the past several years. According to the adjusted timetable as shown in

Figure 2, cadets have received intensive military training at night or dawn with the concentration of human and material resources, and have had time for rests and maintenances in air-conditioned facilities during the daytime (i.e., preparation for night training, medical treatments, counseling, fitness training and relaxation). Consequently, these measures separated the training time and the activity time of the residents, so that the inconveniences caused by the training were naturally resolved.

4.4.2. PS Mechanism II

Securing safety; the adjustment of the training time has solved the watering problems of the Goe-san residents, but the institution made it possible to secure enough living water that is essential for the prevention of waterborne infectious diseases. Meanwhile, under the meteorological conditions of the Goe-san area in the summer day described above, if the cadets overcome the combat loads and run the training programs, patients with thermal injuries can sharply increase including those who may be possible to be transferred to a hospital for emergency reasons. Furthermore, the military evacuation hospital is likely to miss the golden hours, as it takes more than an hour to reach the hospital by land. In addition to the training time adjustment to reduce the damages caused by the heat waves, KACMS has concentrated on the medical staffs and installed the simple shower facilities in the area where the heat injured patients are frequent. Additionally, the school has established the medical service support agreement with the private general hospital in the neighboring area. The private medical institution in the region has been able to promote corporate values by securing additional medical care results in addition to the local people, along with the promotion of social value of the medical support for defense personnel.

4.4.3. PS Mechanism III

Ensuring safeguard for human rights of soldiers and cadets; KACMS has strived to identify and systematically secure the needs of its soldiers and cadets on human rights. This institution has increased the importance and priority of human rights education, shifted the its method for officer cadets from irregular educations to regular courses, and cultivated instructors specialized in human rights. The organization has taken measures such as observations, interviews, and regular surveys to prevent and identify early cases of human rights violations that may occur. In order to guarantee the human rights of female cadets whose numbers are increasing every year, the institution provides separate residential facilities for female cadets and takes preventive measures against digital sexual crimes. Also, the agency strengthens the relevant systems so that if human rights violation cases are identified, rapid and timely feed-backs can be achieved in accordance with legal procedures and military regulations.

Convergence Strategy (CS) with Stakeholders and Communities is being implemented with three mechanisms based on the Establishing Sustainable Cities, Revitalizing Regional Economies, and Preserving Natural Ecology, which are selected by the Korean government as well as the United Nations.

CS Mechanism I

Supporting for Sustainable Urban Construction; Goe-san County has been attempting to diversify its policies of increasing the number of permanent residents in the midst of the aging population along with continuous decrease in the population, but has failed to achieve clear results and has no policy options [

58]. KACMS is guiding its executives to transfer their resident registration sites to Goe-san and providing incentives prepared by the local government. In addition, the agency cooperates with the Goe-san LEA (Local Education Authority) to guide and support kindergartens, elementary, middle, and high schools in the area to educate the children of the executives. These activities not only satisfactorily fulfill the necessities to provide quality education for the children of the executives who have migrated to Goe-san area, but also provide the number of students required to maintain the size of the school in the County. The institution also supports government efforts to ensure the right to education for elementary school students living in mountainous areas where there is no educational facility to develop their talents besides regular educational institutions, by providing education programs they want and donating the talents of its soldiers. It has also been inviting local residents in ROTC cadets festivals and military band performances to meet their cultural needs.

CS Mechanism II

Aiding regional economic activation; since KACMS is a typical administrative organization operated by the government budget rather than for profit generating organizations, the mechanisms for generating economic values are very limited and cannot be fully activated. However, the agency purchases items needed for the operation and maintenance of the institution in Chung-buk province including Goe-san county at a cost of 40 million U$ a year, even though the price competitiveness of the products is somewhat weak. The military school has also been making efforts to help small business owners and farmers in the region by providing souvenirs or encouragements to visitors and their soldiers by purchasing local specialties or gift certificates. It is estimated that about 50,000 school visitors a year, including cadets and their relatives, are consuming about 8.5 million U$ per year on public transportations, accommodations, and restaurants in the area using the local information provided by the institution on-off lines. Meanwhile, KACMS employs Goe-san residents in 54 job positions, including kindergarten teachers, facility managers, cook assistants, which are directly operated by the school. Moreover, the military school is providing reserve officers with facilities for the purpose of the home-coming day, athletic festivals and regular meetings to boost their self-esteems and senses of belonging, and to help revitalize local economies through their consumption activities in the region.

CS Mechanism III

Assisting of Environmental Management Policy; KACMS, which is twice the size of Yeoui-do, Seoul, consists of training sites and a residential area. The area where the training sites are located is in the form of a jungle in which 30 to 50 years old bushes are growing densely. In terms of forest managements, this is not only injurious to health and low in economic value, but also increases the risk of landslides in some areas. From the military standpoints, these forests limit the visibilities for the guard, and are inadequate for training sites because they are not easily accessible to training personnel. KACMS has worked with the Chung-buk Forest Service and Goe-san County Office to improve these natural statuses and to effectively manage the natural ecology. The institutions turned 41.5 hectares wild forest into healthy one in the winter of 2017 and will change another 17.5 hectares wild forest by 2019. KACMS also conducts conservation activities along with field cleaning, mobilizing 20,000 annual training forces for major rivers and nearby hills being used by cadets as training areas. In the case of damages caused by heavy rains or droughts in the area, the school preemptively supports their internal and external resources, thereby reducing the social problems common to rural areas, such as low disaster recovery priorities, the lack of municipal personnel, equipment and budgets needed for recovery. In addition to these natural ecological managements and disaster recoveries support activities, the institute is taking efforts to realize government’s environmental management policies (i.e., non-point source pollution reduction, waste water treatment, radon abatement, soil pollution survey, prevention of air pollution by military vehicles, etc.).

4.5. Performance of CSV Strategies of KACMS

KACMS has difficulties in providing visible and objective data on the question about "What kinds of performance have you created?". These are caused by the limitation of qualitative research methodology and insufficiencies of the evaluation index and methods to measure social values. More than anything, the major drawback is the short duration that KAMCS had to implement CSV strategies. Although it is limited to adequately account for causal relationships between the strategies and the performances of the institution, the performances have been assessed through the analysis of secondary data (i.e., results of surveys conducted by professional research institutes including self-questionnaires, results of training performance assessments conducted by senior command, patient medical records, data of local governments and related organizations, media reports, etc.).

Promoting the Intrinsic Values of Military Training Institution; the unique values that KACMS has promoted through the CSV strategy are as follows; 1) As the results of the 2017 comprehensive assessment for the 4th grade ROTC cadets, who would soon become officers, the failure rates decreased by 41.8% compared to that of the previous year. Failure rates of marksmanship training decreased to less than 1%. These improvements of grades were analyzed as the results of significant increases in practical training time for each individual. 2) According to the questionnaire survey on the satisfaction with the adjusted training programs for the cadets who passed through the summer military training programs in 2017, more than 90% answered ‘Helpful’, and 95.9% of the third grade cadets hoped that the modified training programs would continue. 3) As the outcomes of mechanisms related to ensuring safety, no patients were transferred due to thermal injuries during the training, and the number of patients decreased by 27.7% (1400 cases) compared with that of the previous year. Additionally, the number of cases involving human rights violations has been declining year by year, and by 2018 it has decreased by more than 50% compared to the previous year. 4) The impact of KACMS’s CSV strategy on internal members can be confirmed indirectly through the 2017 Army Morale Measurement Results conducted by the KIDA on trainees and assistants immediately after the conclusion of the summer military training. The data show that the morale levels of this agency is higher than the army average by 1.8% for ‘personal’, 8.8% for ‘units’ and 4.8% for ‘combat readiness’. In particular, the levels of morale associated with ‘mission performance’ and ‘pride’ factors were 100%. 5) While there is a decreased number of complaints from local residents such as noises, dusts, crop damages and traffic disturbances over the training, the number of domestic media reports concerning CSV strategies of the agency has been dramatically increased (33 cases in 2017, and 39 cases as of October 2018).

Creating Social Values of Communities; the Convergence Strategy with Local Community and Stakeholders strategy has developed by KACMS to create local social values is tailored to the characteristics of the agency with the "Convergence Strategy with Partners and Communities" [

22]. The social values of the community created by KACMS are; (1) The chronic "Lack of Water" problem that residents of Goe-san region experienced during the training session was temporarily resolved, and the Goe-san Office of Waterworks plans to increase drainage near KACMS area by 2019 for stable water supply. (2) Execution of national and auxiliary funds by KACMS up to

$35 million a year, use of indirect costs up to

$8 million a year, and purchases of local products and agricultural products are increasing local consumptions. (3) Creating direct employments of KACMS for welfare and military facilities managements. (4) According to the local tax payment data of Goe-san County, residents and automobile taxes are increasing as the number of KACMS executives and their families migrate to Goe-san County. As of October 2018, the growth rate of resident taxes and automobile taxes increased by 300% and 37.96%, respectively based on the number of cases compared to 2016, which is before the implementation of the strategy. It also promotes the brand values of Goe-san County all over the nation by providing local information to about 50,000 trainees and visitors annually. (5) The institution is leading the way in implementing the government’s environmental management policies, generating the social values established by the United Nations through improving forests in the training site, implementing natural protection activities for major rivers and hills in the region, and quickly recovering damages in case of natural disasters including rains or droughts.

5. Discussion

5.1. Results of Analysis

As a result of the study, the case study presents following findings. First, innovating public services by CSV strategies done by public organization can improve the performance of unique tasks that public organization should perform and the level of safety, human rights within the organization. It can also increase job satisfaction and morale in terms of individual perspective and organization as well. Second, The CSV strategies in establishing cooperative systems based on mutual communications and trust with the community by public organization can improve the sustainability of the region, activate the local economy and contribute to the conservation and betterment of local environment. So, the CSV strategies pursued by public organization can be also good weapons to achieve not only the performance but also sustainability of the organization.

Today, the elements that constitute our society are divided into private companies, public organizations, and civil societies in general, even though their classification standards and methods of expressions are somewhat different according to their perspectives.

Private companies are established and operated for the purpose of maximizing their inherent values, which can be summarized as profit-seeking and maximizing shareholders values. The companies have developed their organizations while balancing between corporate and social objectives and adhering to the laws and regulations of their society. In particular, social value creation activities carried out by corporations are promoted for corporate retention, corporate satisfaction, image enhancement and competitiveness assurance. These activities originated from the first charitable activities, but now they have gone through the steps of internalization of social services, BOP strategy and social enterprises, and now they are developing into sustainability management level.

Meanwhile, the public organizations are organized and function to realize the public interests. They are preparing to change into the Public Value Paradigms by removing the New Public Management (NPM) policy with the global economic crisis that occurred in 2007. The emerging paradigms of administrative academics are raising controversy over the scope of public administration to include social values in the public values. The paradigms also emphasize the public accountabilities of government agencies to use public resources to create public values with corporations and civil societies. On the other hand, civil societies, which are relatively independent of the national apparatuses and the economic markets [

31,

67,

68], act to represent ‘citizen demands’.

One of the differences of CSV and CPV from previous strategies is that their visions and objectives are located in the social sector, which is also called the third sector, neither the government sector nor the private sector. This academic phenomenon is due to the gradual expansion of the social sector as the age of governance becomes more widespread, the boundaries between government and business become increasingly blurred, and the governmental organizations converge with the capitalism and socialism they stand for.

5.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

This study attempted to find the social value creation strategy suitable for the characteristics of public organizations through the case of KACMS in the above academic backgrounds and political social phenomenon. Although the CSV activities currently underway in KACMS are evaluated to be at the initial stage of introduction, the agency has overcome the administrative, voluntary and political constraints arising from the characteristics of government agencies [

69,

70,

71] and has achieved remarkable results. Based on the results of the case study, several theoretical and practical implications have been made.

First, this research supports the appropriateness and necessity of the precedent researchers’ claims that public organizations should lead social value creation activities. Furthermore, it is considered that government agencies should be added to the existing subjects on the shared value creation activities (i.e., enterprise-led, social led, and multilateral cooperation type) [

53]. This is because the nature of activities for solving social problems in recent years is difficult to solve by only a specific social organization. It is effective to create synergy by cooperation of various types of social organizations. In particular, the goals of the CSV strategies are to provide understandings and solutions to social agendas that may be somewhat unfamiliar to businesses. Collaborations with government agencies capable of addressing these organizations can be the key to successful completion of this strategy.

Second, in order to achieve a higher level of social value creation strategy in rural areas such as Goe-san, it is advantageous for government agencies or public institutions to recognize and solve social problems more easily than local private companies or civil societies with weak organizational structures. For the operating CSV strategies, it is necessary to establish the cooperative relationships between the central and the local governments, to build partnerships between private and public institutions, and to try new approaches such as the establishment of the network governance systems that include the CBOs and NGOs.

Third, in particular, public organizations need to identify social values that are faithful to constitutional values and their purposes of establishment, and to reflect them in the organization’s visions and goals. In order to strengthen accountabilities for the social value-creating activities of public organizations, projects related to social values must be reflected in the organization’s plans separately from the general projects. It is also necessary to build the performance evaluation systems suitable for social projects and establish network governance of the local or business units centered on public organizations. For key participants in network governance, it is desirable to provide educational programs to promote social values and promote Public Service Motivation (PSM). In order to disseminate shared value creation strategies to public organizations including central government agencies, additional researches are needed on the characteristics of leadership, organizational culture, and motivating factors of public organization directors.

For the following reasons, the result of research raises the need to develop the "Realizing Social Value (RSV) strategy" that should be applied to both companies and public institutions, apart from corporate-oriented CSV Strategies or government-centered Public Value Paradigms.

First, the social values are distinguished from public values for the purposes of realizing the public interests, and are clearly distinguished from enterprise values such as profit seeking or maximization of shareholder profits. Whether the social values are included in the private sector or the government sector, there is a possibility that the visions or goals of the strategies become ambiguous. If the intrinsic values of the organization are threatened during the execution of the strategy to create social values, the social values are likely to be relatively weakened or diluted.

Second, CSR or CSV strategies are the business strategies developed for the purposes of promoting the sustainable management possibilities from the perspectives of the corporation. The public value paradigms are new administrative management strategies for the public organizations that are developed for the purposes of realizing the public interest. Whether it is a CSR strategy or a CSV strategy, it is expected to face a number of obstacles in the process of the strategy when it is used to solve the social problems, which are non-professional fields. Borrowing a strategy that is being used for other purposes because we do not have a professional strategy for solving social issues is like using a dagger or utility knife instead of a kitchen knife because the cook does not have the kitchen knife needed for cooking. In this case, subjects who want to realize social values will face obstacles such as inconveniences and dangers that a chef will experience. These obstacles will limit the precise identification of social issues in the planning stage, limit the developments of the necessary resources and mechanisms in the implementation process, and limit the capacity to explain the causal relationships between strategies and performances at the evaluation phase.

Third, the strategies of business and administrative academia, which have recently attracted attention for solving social issues, have been proposed to be used in creating social values together, while faithfully keeping their original values. These strategies appear to positively reflect the needs of stakeholders or civil societies to help enterprises or government organizations for solving social problems outside their own boundaries. Stakeholders or the public will require that related companies or government agencies be adhered to their own sphere rather than solving social problems when they encounter unwanted side effects (i.e., undermining organizational values, increasing social costs, and the infringement of vested rights). After all, it is very likely that related companies and government organizations are weakening or hollowing out the areas related to social value creation.

5.3. Limitatins and Future Research

Several limitations of the research suggest potential directions for future research. First, the findings and implications are based on a single case although one of the major advantages of the case research is the depth of the information that can be collected. To expand generalizability, the findings of the study should be tested with extended and/or multiple case studies applied to a variety of public sectors. Second, considering the nature of CSV strategies, the analysis period of the research is short for the analysis so future research should be based on testing longer time-span. Third, the case-based research method alone applied to the study is difficult to generalize the results so future studies should try on empirical studies with diversified constructs.

6. Conclusions

This study analyzed the case of KACMS to assess whether CSV strategies applied by private organizations to pursue sustainable management and social value creation together can be also applied to public organizations, and to identify how public organization who offers military service can enhance its core competitiveness through CSV strategies while addressing social, environmental, and economic issues to achieve sustainability.

In conclusion, the study has two major findings. First, public organizations may not only realize their intrinsic values more effectively through CSV strategies, but may also create social values such as sustainable urban construction, regional economic growth, and environmental management in line with UN SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals). Second, what distinguishes KACMS from other public organizations in dealing with CSV strategies is that the agency has sought to accurately identify community issues in the process of realizing its own value. In addition, the agency is internalizing social value creation to its important organizational value and using the CSV strategy to resolve these matters. The case study shows that public organizations can use CSV strategies to create social values, albeit limited. However, from the standpoint of the public organizations, it is reasonable to assume that the social values achieved by this institution should be systematically realized the public obligations rather than being created. In short, the results of this study can provide a prototype of the public organization-led CSV strategy and may serve as a useful guidance for exploring strategies to create social values. Based on this study, we expect CSV strategies for various kinds of public organization can be developed in the near future as a follow-up research.