Alternative Product Development as Strategy Towards Sustainability in Tourism: The Case of Lanzarote

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainability within Tourism Development

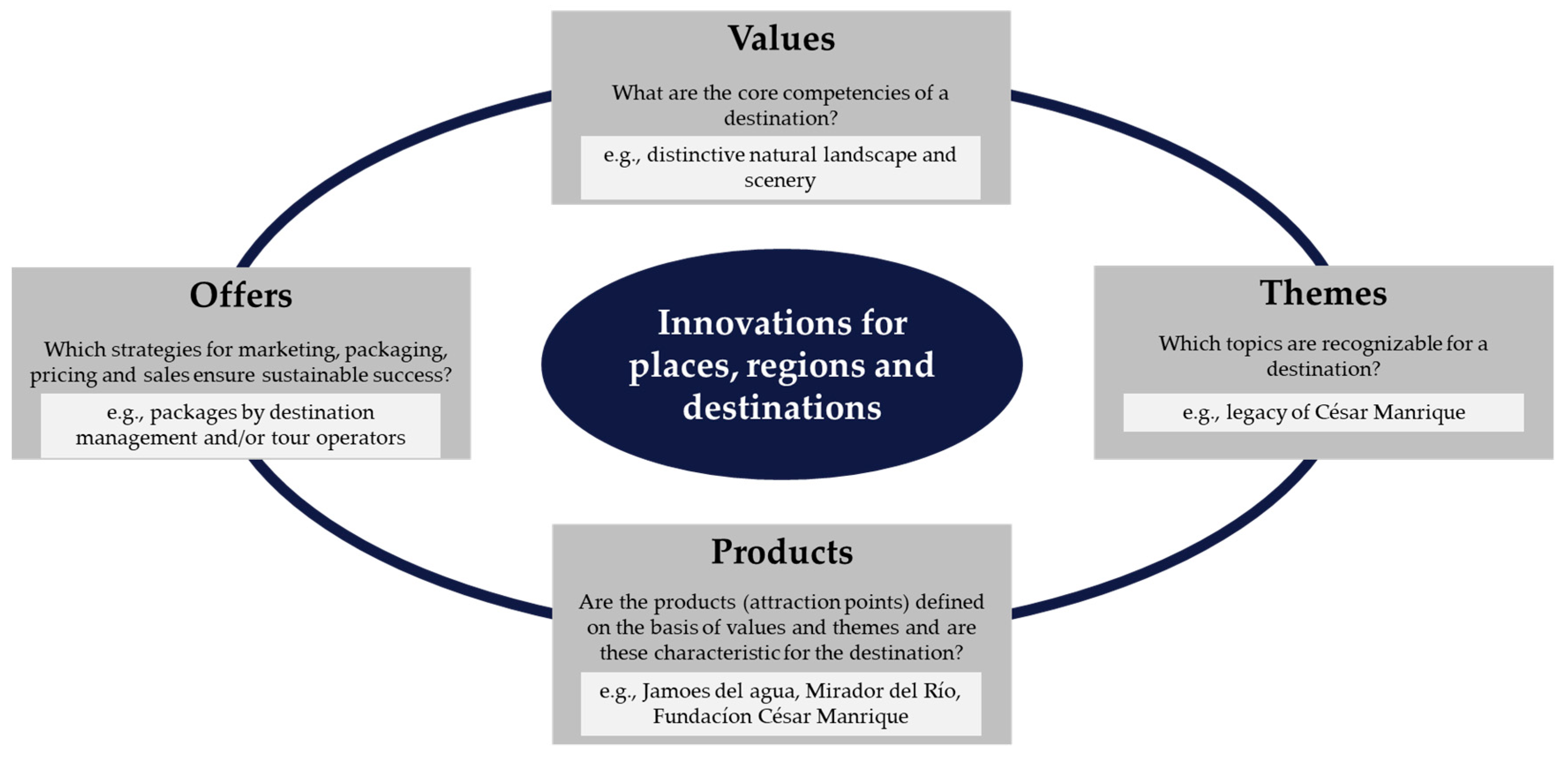

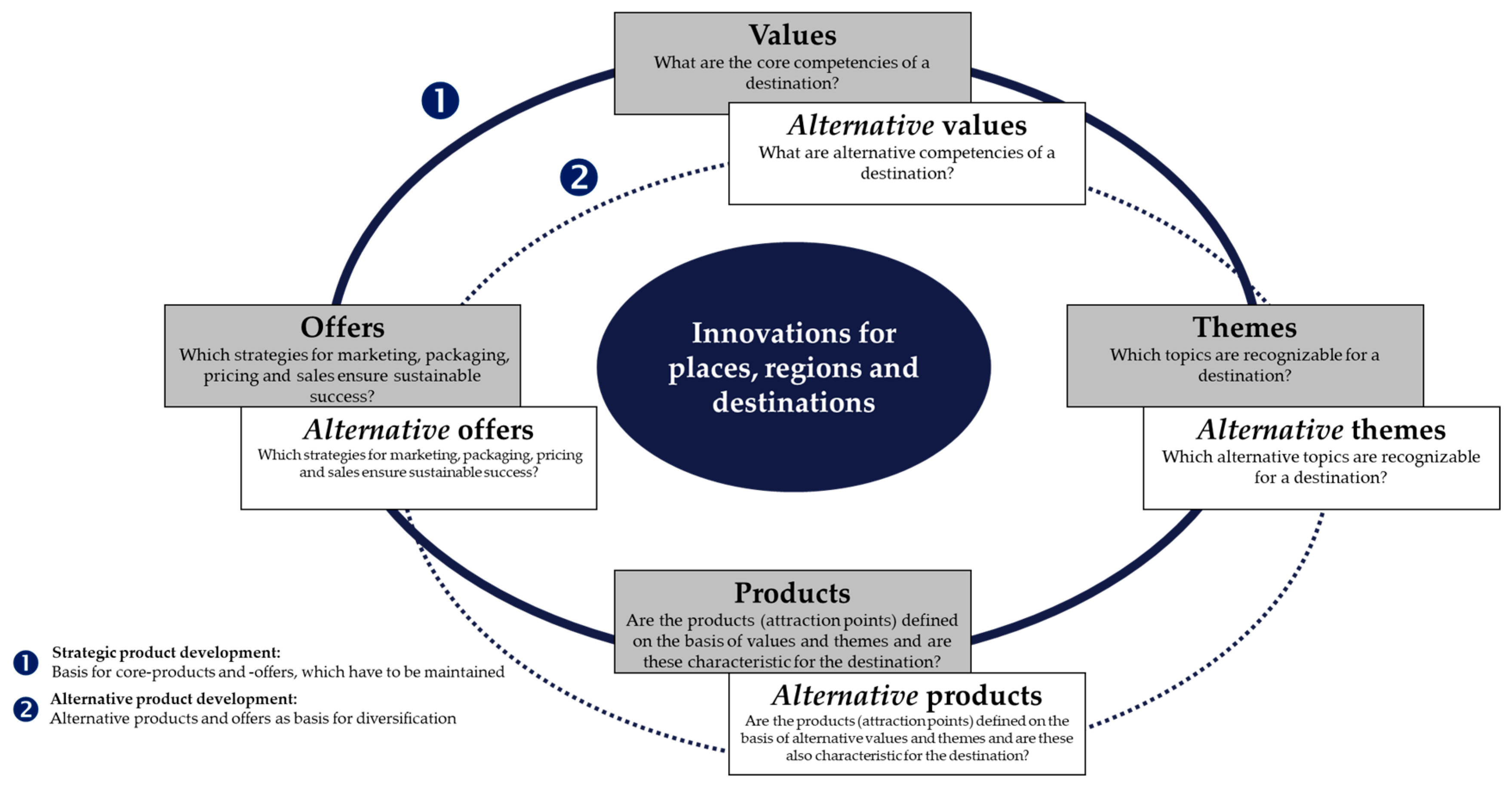

2.2. Strategic Product Development

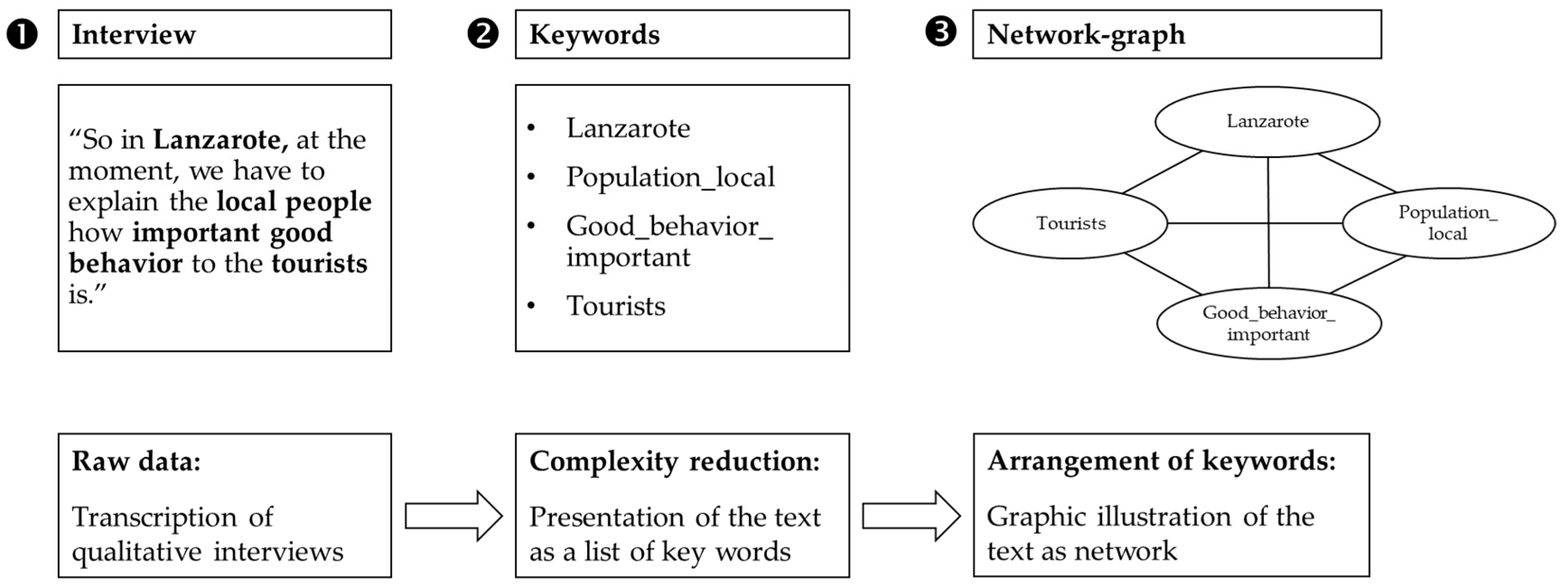

3. Methodology

4. Results

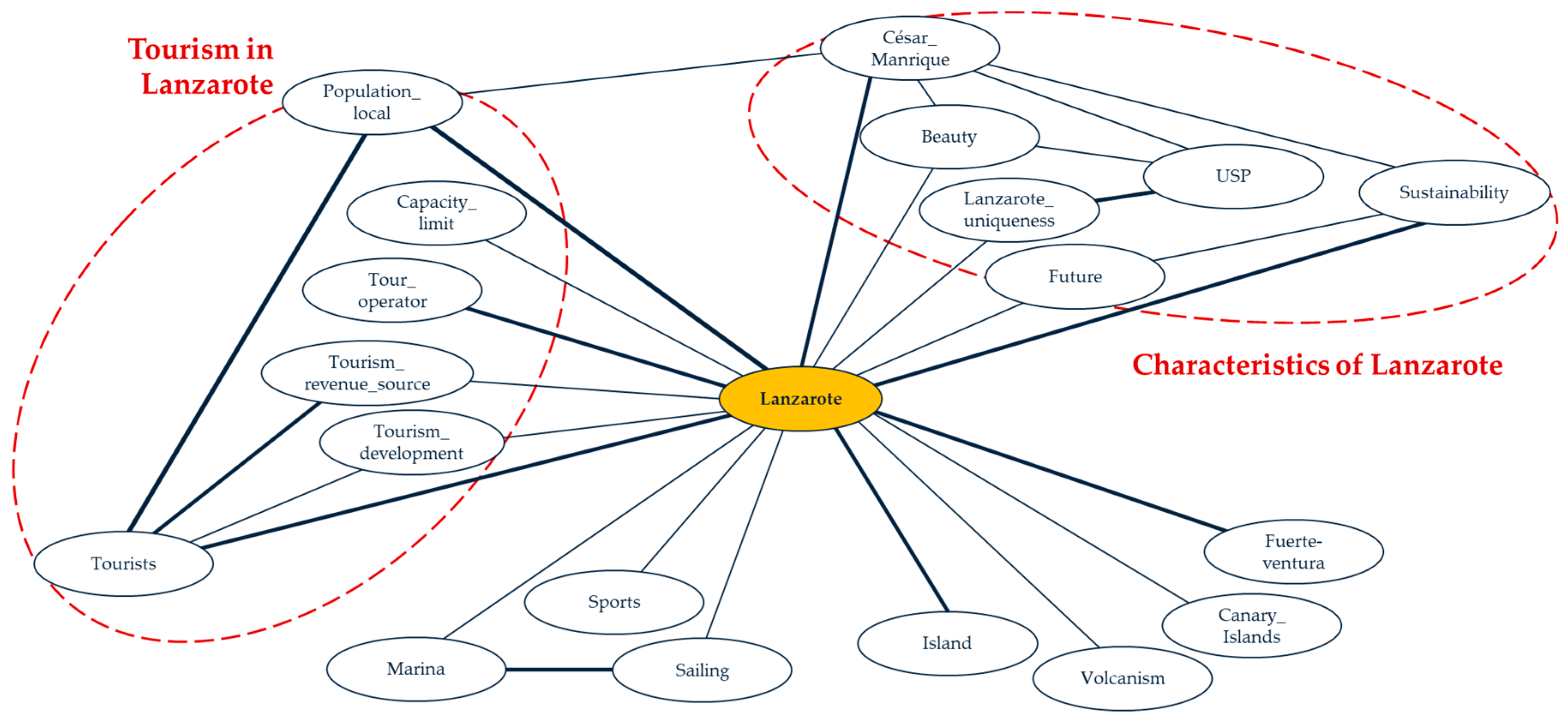

4.1. Lanzarote: Central Associations

“[César Manrique] told the people: Listen, what you are doing here is incredible special, you grow wine on a climate where there is no rain. What you are doing is special, and it is particular to here. And this island has a great capacity for tourism. And [César Manrique] helped the people to understand that this space was special. That we are very lucky to live here, but we need to protect it.”(Interviewee 1)

“In the end César [Manrique] achieved the acceptance of a sustainable tourism model on the island, which lasted for many years. And he developed different places on the island, which define this uniqueness until today. However, for him it was always important to see Lanzarote as a whole, and not tolerate only on single places. This was his legacy.”(Interviewee 4)

“The island has more tourism now than ever! The tourists are falling out of the sky, this never ever happened like that. Lots and lots of different systems and dynamics have converged to make this the most profitable time ever for the island.”(Interviewee 1)

“We see, if we put the focus on growing, having more tourists, at the end of the day this is the catastrophe for the destination.”(Interviewee 2)

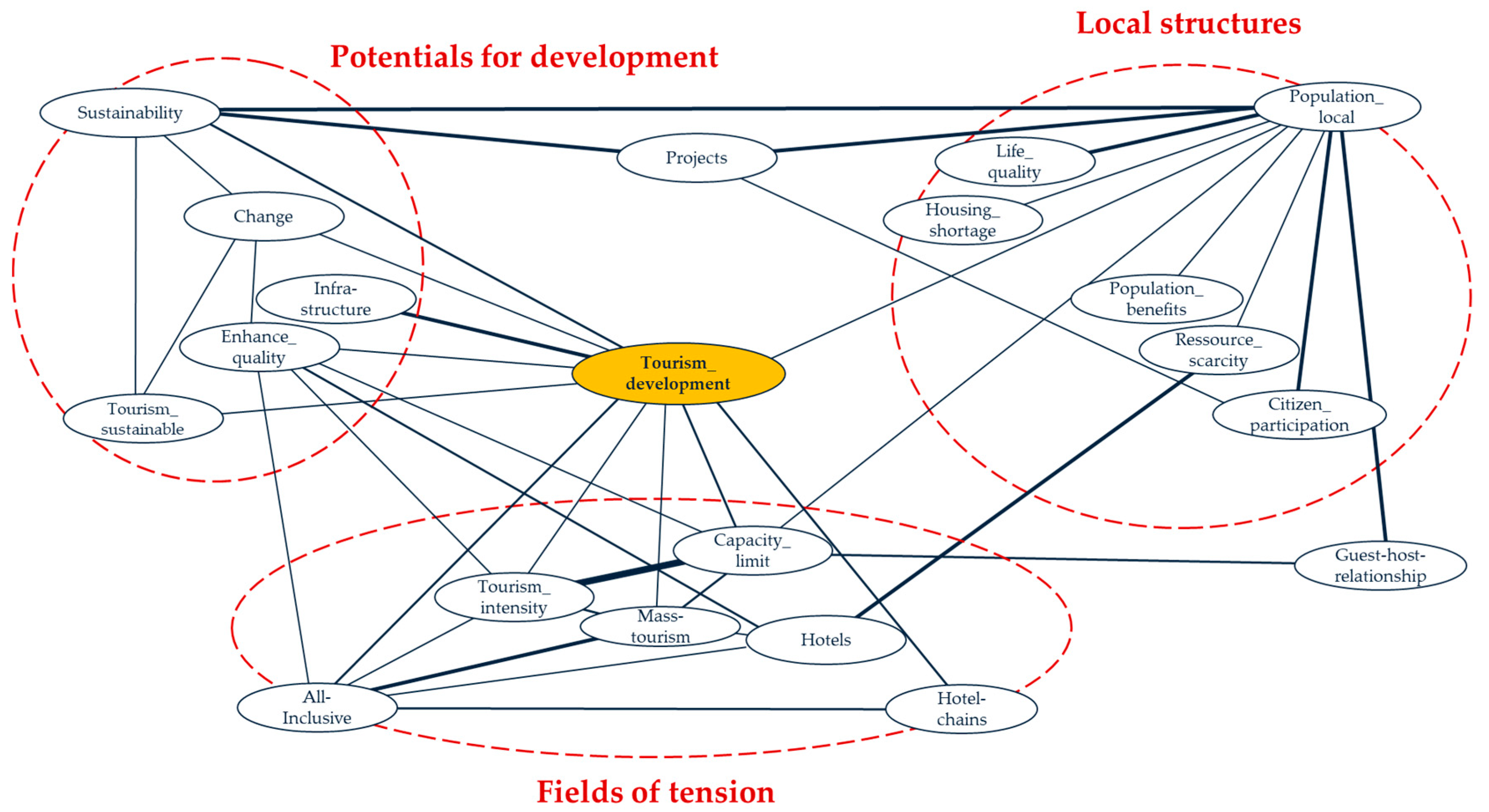

4.2. Tourism Development on Lanzarote

“[…] because this is a tiny island, resources are limited. And we have no water for everybody, unfortunately. Sometimes, I don’t have water in my house, but tourists always have water in their hotel. I think that’s not fair!”(Interviewee 5)

“Tourists come with all-inclusive in the hotel and they go from the airport to the hotel and they don’t visit anything [on the island]. Just sitting at the swimming pool all day, because it is all-inclusive. And afterwards, they go to the airport, they go back home.”(Interviewee 10)

“We are [currently] for example at over 90% occupancy, which is almost at the limit of the island.”(Interviewee 3)

“There was a time when the contact between tourists and locals was very good, but now that’s not the case anymore. It is not a conflict yet, but they are moving towards it.”(Interviewee 4)

“[In the past,] they just wanted the numbers: more airplanes, more hotels, more and more numbers […]. And that’s where the worry starts: we are going to try to get better quality! You have to do it by renovating accommodation, improving the infrastructure, the security, the experience, educating all the workers, bringing the hygiene up to a certain level, and bit-by-bit the prices start to increase. But it doesn’t happen overnight.”(Interviewee 3)

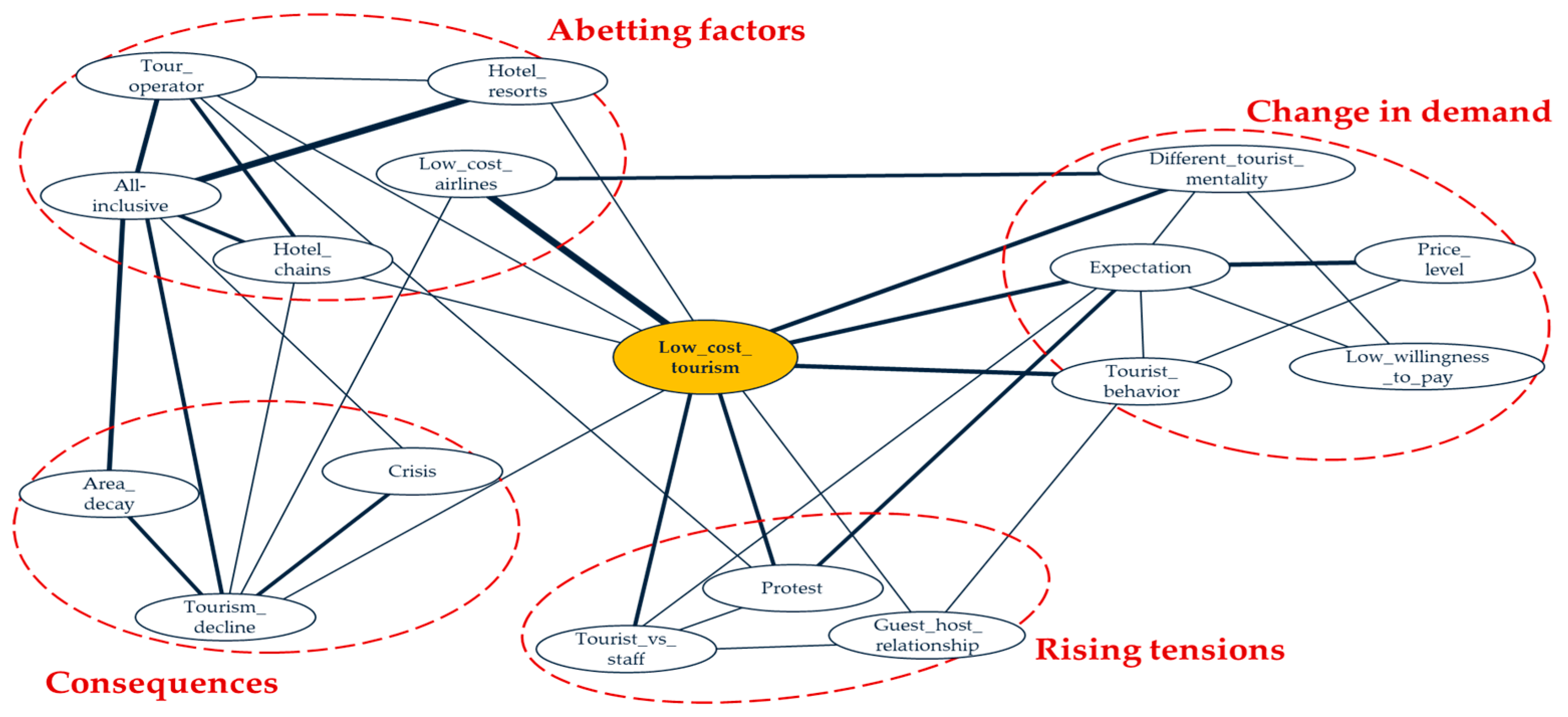

4.3. Low-Cost Tourism on the Island of Lanzarote

“The all-inclusive model, the big hotel model, does not leave a lot of money on the island. What it does, though, is creating employment, and legal employment where people have contracts. They employ a lot of people, these hotels. So, from that point they do help the economy. But from the local business person, who has a shop on the street, from that point, they do not create a lot.”(Interviewee 3)

“The problem here lies on these people who spend their money not in the destination, but in the home country. Because these all-inclusive hotels are normally managed by tour operators which are not located on the island. So business is not here, it is outside.”(Interviewee 5)

“This can be seen especially if you go to the three tourist centers. [Tourists] come here and leave no penny. That means most of them barely get out of their [hotel], they paid three meals a day, and then all the snacks are added. And if they ever come out then they will do a bus tour […]. But let’s say individual tourists leave more money here than these mass tourists.”(Interviewee 9)

“The mentality of the people [has changed]: it cannot cost anything more, they want everything, but it should not cost anything. But on the other side they feel like a guest, they want to be treated like a king. All the tourism here, all the people who come here are not the same people than before.”(Interviewee 8)

“The locals are very hospitable. But sure, there comes a moment where you feel uncomfortable and restricted. We can remain hospitable, but with limited capacity, that’s the key. Tourism is good and important, but in a limited and fragile area like this, it just has to be controlled. And this is not only for Lanzarote, but for every tourist destination. We can currently see that in some major European cities which conflicts mass tourism brings with it.”(Interviewee 4)

“There’s very little else on the island to provide an income for the local people. So yes, in the downturns when you see the—not revolts—but the real problems, people’s attitudes towards tourism in the downturn. In the upturn, I think, most people are benefitting, so most people are happy. But, it’s very dynamic, very, very complicated to keep an island like this. Constantly developing, constantly growing, creating more wealth, but at the same time sustaining it aesthetically, sustaining the infrastructure and keeping the quality of the tourism: this is very hard to balance.”(Interviewee 3)

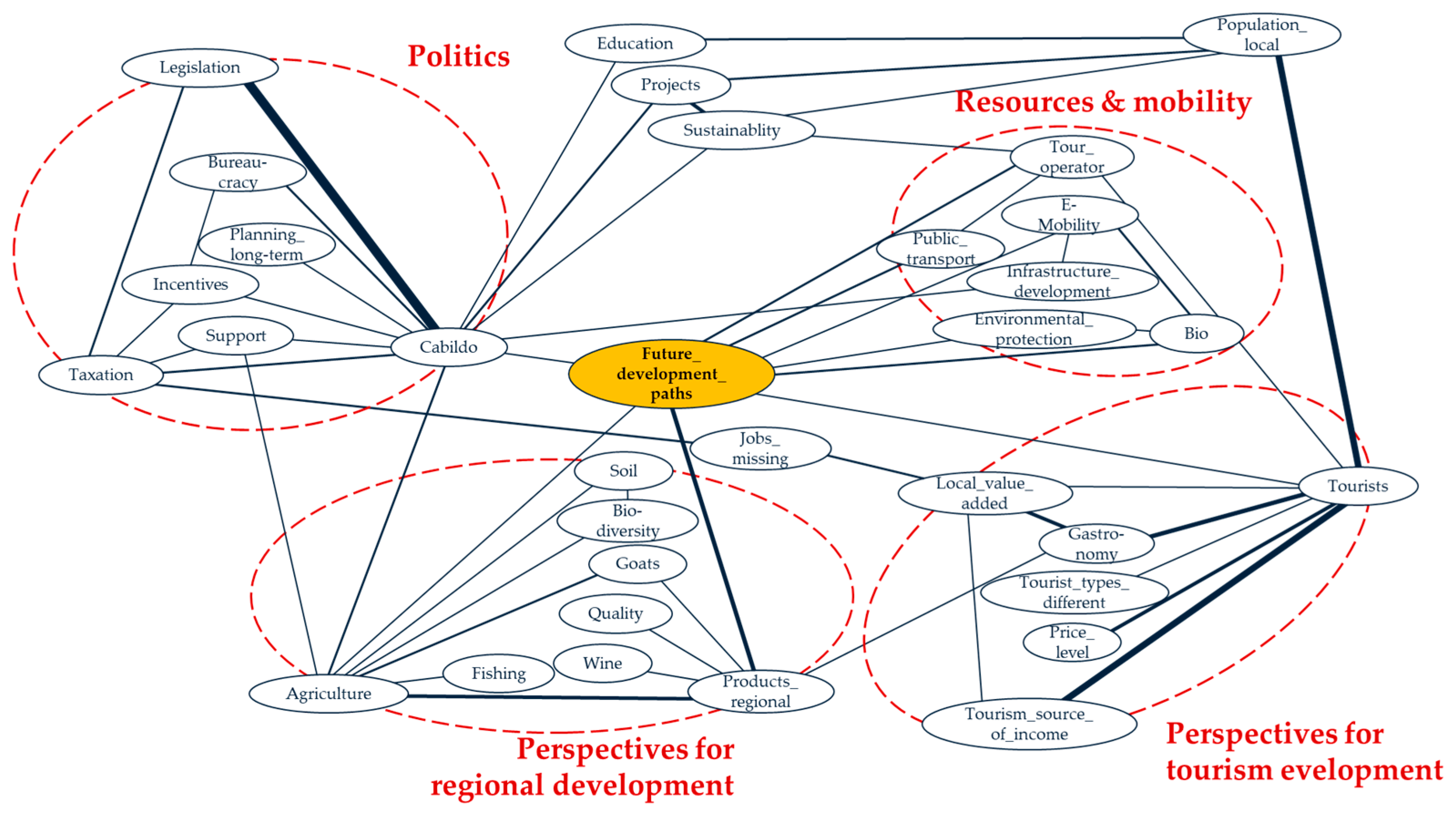

4.4. Future Development Paths

“So if they want to use another energy, we have plenty of sun and light. We wouldn’t really need the geothermic energy, because we have a lot of alternatives, but they keep depending on petrol.”(Interviewee 7)

“If I were a politician, I would say: no gasoline cars any longer, only electric cars and public transport! There are no distances. You could organize the traffic network in a different way.”(Interviewee 8)

“I think the main thing is to improve the quality of tourism and to make sure that the tourists that come here are not just for one reason, but for many reasons. To sample the food, sample the culture, to do sports, go diving, take part in ironman, to do excursions. I think you want the tourist to be interested in all this. […] You need to diversify, you need to offer extra things.”(Interviewee 3)

“It´s a way to increase the expenditure, every day from each tourist. […] We consider we have margin to have a higher expenditure every day if the tourists want to taste everything, you know, go to La Geria, La Vegueta, to taste our gastronomy. Automatically, the expenditure every day is going to grow.”(Interviewee 2)

“Big hotels mostly do not want these new activities because it is against their interests. The monopolies are directed against this type of privately-mediated tourism. The political instability, the constant change, is responsible for this and cannot develop a continuous model. Of all the positive upswing, only the rich ones profit. There is a lot of talk here about the legal discrepancies, but that’s not true. We have laws that exist, but they are not applied in the right form. The law must run parallel to the political decisions.”(Interviewee 4)

“Cooperative farmers bring their onions to the cooperative, but the Cabildo is hesitant about paying. That can be improved. If you pay the farmers punctually and quickly then they will start to cultivate again next year, but if you do not pay them, they will stop and you will not grow anymore. They say: What is that supposed to be? Why should I do that?”(Interviewee 6)

5. Alternative Product Development: An Adjusted Strategy for Sustainable Tourism Development

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pechlaner, H.; Tretter, M. Von der Kernkompetenz zum Produkt—Innovationen in Destinationen durch Strategische Produktentwicklung. In Kulturtourismus zu Beginnn des 21. Jahrhunderts; Quack, H.-D., Klemm, C., Eds.; Oldenbourg: München, Germany, 2013; pp. 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Romero, A.; Blázquez-Salom, M.; Cànoves, G. Barcelona, Housing Rent Bubble in a Tourist City. Social Responses and Local Policies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M. Current sharing economy media discourse in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 60, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forno, F.; Garibaldi, R. Sharing Economy in Travel and Tourism: The Case of Home-Swapping in Italy. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2015, 16, 202–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. On the mobility of tourism mobilities. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joppe, M. Tourism policy and governance: Quo vadis? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvioni, D. Hotel Chains and the Sharing Economy in Global Tourism. Symph. Emerg. Issues Manag. 2016, 1, 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Signorile, P.; Larosa, V.; Spiru, A. Mobility as a service: A new model for sustainable mobility in tourism. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2018, 10, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zervas, G.; Proserpio, D.; Byers, J.W. The Rise of the Sharing Economy: Estimating the Impact of Airbnb on the Hotel Industry. J. Mark. Res. 2017, 54, 687–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Von Bergner, N.M.; Lohmann, M. Future Challenges for Global Tourism: A Delphi Survey. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, C.; Zacher, D.; Pechlaner, H.; Namberger, P.; Schmude, J. Strategies and measures directed towards overtourism: A perspective of European DMOs. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herntrei, M. Wettbewerbsfähigkeit von Tourismusdestinationen: Bürgerbeteiligung als Erfolgsfaktor? Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Benur, A.M.; Bramwell, B. Tourism product development and product diversification in destinations. Tour. Manag. 2015, 50, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B. Mass Tourism, Diversification and Sustainability in Southern Europe’s Coastal Regions. In Coastal Mass Tourism: Diversification and Sustainable Development in Southern Europe; Bramwell, B., Ed.; Channel View: Bristol, UK, 2004; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Nunkoo, R. Tourism development and trust in local government. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, F.; García Quesada, M.; Villoria, M. Corruption in Paradise: The puzzling case of Lanzarote (Canary Islands, Spain). XXII Pisa World Congress of Political Science. 9 July 2012. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266323816_Corruption_in_Paradise_the_puzzling_case_of_Lanzarote_Canary_Islands_Spain (accessed on 14 June 2019).

- Santana-Talavera, A.; Fernández-Betancort, H. Times of Tourism: Development and Sustainability in Lanzarote, Spain. In Tourism as an Instrument for Development: A Theoretical and Pracitcal Study; Fayos-Solà, E., Ed.; Emerald: Bingley, UK, 2014; pp. 241–264. [Google Scholar]

- Canary Islands: Tourist Arrivals. Historical Data: 1997–2018. Available online: https://turismodeislascanarias.com/sites/default/files/promotur_serie_frontur_1997-2018_en.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2019).

- Canary Islands: Lanzarote: Profile of Tourists. Available online: https://turismodeislascanarias.com/sites/default/files/promotur_visita_mas_de_una_isla_lanzarote_2017_en.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2019).

- Wang, S.; Chen, J.S. The influence of place identity on perceived tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 52, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.S.; Paramati, S.R. The impact of tourism on income inequality in developing economies: Does Kuznets curve hypothesis exist? Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 61, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- García, F.A.; Vázquez, A.B.; Macías, R.C. Resident’s attitudes towards the impacts of tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 13, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L.; Valentine, K.M.; Knopf, R.C.; Vogt, C.A. Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impact. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 1056–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, L.; Cooper, C.; Ruhanen, L. The positive and negative impacts of tourism. In Global Tourism; Theobald, W.F., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 79–102. [Google Scholar]

- Boley, B.B.; McGehee, N.G.; Perdue, R.R.; Long, P. Empowerment and resident attitudes toward tourism: Strengthening the theoretical foundation through a Weberian lens. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 49, 3–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J. How does tourism in a community impact the quality of life of community residents? Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Gursoy, D. Residents’ support for tourism. An Identity Perspective. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. Host perceptions of tourism: A review of the research. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolfani, S.M.; Sedaghat, M.; Maknoon, R.; Zavadskas, E.K. Sustainable tourism: A comprehensive literature review on frameworks and applications. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraživanja 2015, 28, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvan, E.; Dolnicar, S. Measuring environmentally sustainable tourist behaviour. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 59, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Frew, A.J. ICT and sustainable tourism development: An innovative perspective. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2014, 5, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavan, B. Sustainable tourism: Development, decline and de-growth. Management issues from the Isle of Man. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.R.B.; Crouch, G.I. The Competitive Destination: A Sustainable Tourism Perspective; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Muresan, I.C.; Oroian, C.F.; Harun, R.; Arion, F.H.; Porutiu, A.; Chiciudean, G.O.; Todea, A.; Lile, R. Local Residents’ Attitude toward Sustainable Rural Tourism Development. Sustainability 2016, 8, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Delgado, A.; Palomeque, F.L. Measuring sustainable tourism at the municipal level. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 49, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Loorbach, D.; Shiroyama, H. The Challenge of Sustainable Urban Development and Transforming Cities. In Governance of Urban. Sustainability Transitions: European and Asian Experience; Loorbach, D., Wittmayer, J.M., Shiroyama, H., Fujino, J., Mizuguchi, S., Eds.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan; Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA; Dordrecht, The Netherlands; London, UK, 2016; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Edgell, D.L. Managing Sustainable Tourism: A Legacy for the Future; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R.W. Sustainable tourism: A state-of-the-art review. Tour. Geogr. 1999, 1, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovicic, Z.V. Key issues in the implementation of sustainable tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 17, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Delgado, A.; Saarinen, J. Using indicators to assess sustainable tourism development: A review. Tour. Geogr. 2014, 16, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoddard, J.E.; Pollard, C.E.; Evans, M.R. The Triple Bottom Line: A Framework for Sustainable Tourism Development. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2012, 13, 233–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrrell, T.; Paris, C.M.; Biaett, V. A Quantified Triple Bottom Line for Tourism: Experimental Results. J. Travel Res. 2012, 52, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L. Relevance of triple bottom line reporting to achievement of sustainable tourism: A scoping study. Tour. Rev. Int. 2005, 9, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, S.; Nyaupane, G.P.; Budruk, M. Stakeholders’ Perspectives of Sustainable Tourism Development: A New Approach to Measuring Outcomes. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization International Network of Sustainable Tourism Observatories. Available online: http://insto.unwto.org/about/ (accessed on 17 May 2019).

- Byrd, E.T. Stakeholders in sustainable tourism development and their roles: Applying stakeholder theory to sustainable tourism development. Tour. Rev. 2007, 62, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waligo, V.M.; Clarke, J.; Hawkins, R. Implementing sustainable tourism: A multistakeholder involvement management framework. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, A.; Miles, S. Developing stakeholder theory. J. Manag. Stud. 2002, 39, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, A.; Hunter-Jones, P.; Warnaby, G. Are we any closer to sustainable development? Listening to active stakeholder discourses of tourism development in the Waterberg Biosphere Reserve, South Africa. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Timur, S. Stakeholder involvement in sustainable tourism: Balancing the voices. In Global Tourism; Theobald, W.F., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 230–247. [Google Scholar]

- Jamal, T.; Stronza, A. Collaboration theory and tourism practice in protected areas: Stakeholders, structuring and sustainability. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhanen, L. Local government: Facilitator or inhibitor of sustainable tourism development? J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 80–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sautter, E.T.; Leisen, B. Managing Stakeholders. A Tourism Planning Model. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.; Twining-Ward, L. Monitoring for a Sustainable Tourism Transition: The Challenge of Developing and Using Indicators; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Liu, J.; Wei, Z.; Li, W.; Wang, L. Residents’ Attitudes towards Sustainable Tourism Development in a Historical-Cultural Village: Influence of Perceived Impacts, Sense of Place and Tourism Development Potential. Sustainability 2017, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Cañizares, S.M.; Castillo Canalejo, A.M.; Núñez Tabales, J.M. Stakeholders’ perceptions of tourism development in Cape Verde, Africa. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 966–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Belhassen, Y.; Shani, A. Three Tales of a City: Stakeholders’ Images of Eilat as a Tourist Destination. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 702–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collis, D.J.; Montgomery, C.A. Competing on resources: Strategy in the 1990’s. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1995, 73, 118–128. [Google Scholar]

- Denicolai, S.; Cioccarelli, G.; Zucchella, A. Resource-based local development and networked core-competencies for tourism excellence. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flagestadt, A.; Hope, C.A. Strategic success in winter sports destinations: A sustainable value creation perspective. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 445–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikkemaat, B.; Peters, M.; Chan, C.-S. Needs, drivers and barriers of innovation: The case of an alpine community-model destination. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugland, S.A.; Ness, H.; Grønseth, B.-O.; Aarstad, J. Development of Tourism Destinations. An Integrated Multilevel Perspective. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 268–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechlaner, H.; Fischer, E.; Hammann, E.-M. Leadership and Innovation Processes–Development of Products and Services Based on Core Competenies. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2006, 6, 31–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A.D. Exploring a developing tourism industry: A resource-based view approach. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2017, 42, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Pechlaner, H.; Hammann, E.-M.; Fischer, E. Leadership und Innovationsprozesse. Von der Kernkompetenz zur Dienstleistung. In Erfolg durch Innovation: Perspektiven Für den Tourismus- und Dienstleistungssektor; Pechlaner, H., Tschurtschenthaler, P., Peters, M., Pikkemaat, B., Fuchs, M., Eds.; Deutscher Universitäts-Verlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2005; pp. 63–87. [Google Scholar]

- Pechlaner, H.; Fischer, E.; Hammann, E.-M. Innovationen in Standorten—Perspektiven für den Tourismus. In Strategische Produktentwicklung im Standortmanagement: Wettbewerbsvorteile für den Tourismus; Pechlaner, H., Fischer, E., Eds.; Erich-Schmidt-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2009; pp. 9–29. [Google Scholar]

- Zelger, J.; Lösch, H. Formale und semantische Folgen der Komplexitätsreduktion von GABEK®-Begriffsnetzwerken. In GABEK V—Werte in Organisationen und Gesellschaft; Schober, P., Zelger, J., Raich, M., Eds.; Studien Verlag: Innsbruck, Austria, 2012; pp. 81–103. [Google Scholar]

- Pechlaner, H.; Volgger, M. How to promote cooperation in the hospitality industry—Generating practitioner relevant knowledge using the GABEK qualitative research strategy. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 24, 925–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B.S.; Uysal, M. An examination of the relationship between carrying capacity and the tourism lifecycle: Management and policy implications. J. Environ. Manag. 1990, 31, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seraphin, H.; Sheeran, P.; Pilato, M. Over-tourism and the fall of Venice as a destination. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 374–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilanis, I.; Vayanni, H. Sustainable Tourism: Utopia or Necessity? The Role of New Forms of Tourism in the Aegean Islands. In Coastal Mass Tourism. Diversification and Sustainable Development in Southern Europe; Bramwell, B., Ed.; Channel View: Bristol, UK, 2004; pp. 269–291. [Google Scholar]

- Sadler, J. Sustainable Tourism Planning in Northern Cyprus. In Coastal Mass Tourism. Diversification and Sustainable Development in Southern Europe; Bramwell, B., Ed.; Channel View: Bristol, UK, 2004; pp. 133–156. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R.W. The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. Can. Geogr. 1980, 24, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. The Tourism Area Life Cycle: Conceptual and Theoretical Issues; Channel View: Clevedon, UK; Buffalo, NY, USA; Toronto, ON, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, L. Capital accumulation: Tourism and development processes in Central and Eastern Europe. In Tourism and Transition: Governance, Transformation and Development; Hall, D., Ed.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2004; pp. 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Yasarata, M.; Altinay, L.; Burnes, P.; Okumus, F. Politics and sustainable tourism development—Can they co-exist? Voices from North Cyprus. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eckert, C.; Pechlaner, H. Alternative Product Development as Strategy Towards Sustainability in Tourism: The Case of Lanzarote. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3588. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11133588

Eckert C, Pechlaner H. Alternative Product Development as Strategy Towards Sustainability in Tourism: The Case of Lanzarote. Sustainability. 2019; 11(13):3588. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11133588

Chicago/Turabian StyleEckert, Christian, and Harald Pechlaner. 2019. "Alternative Product Development as Strategy Towards Sustainability in Tourism: The Case of Lanzarote" Sustainability 11, no. 13: 3588. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11133588

APA StyleEckert, C., & Pechlaner, H. (2019). Alternative Product Development as Strategy Towards Sustainability in Tourism: The Case of Lanzarote. Sustainability, 11(13), 3588. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11133588