Intercultural Education for Sustainability in the Educational Interventions Targeting the Roma Student: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Identify the educational context where the intervention has been carried out (school, extracurricular or extracurricular, community or in more than one context).

- Describe the main characteristics of the interventions carried out with Roma students according to the purpose of the intervention, school level, participants and results.

- Assess the implications of the results of the interventions for Roma students.

2. Methods

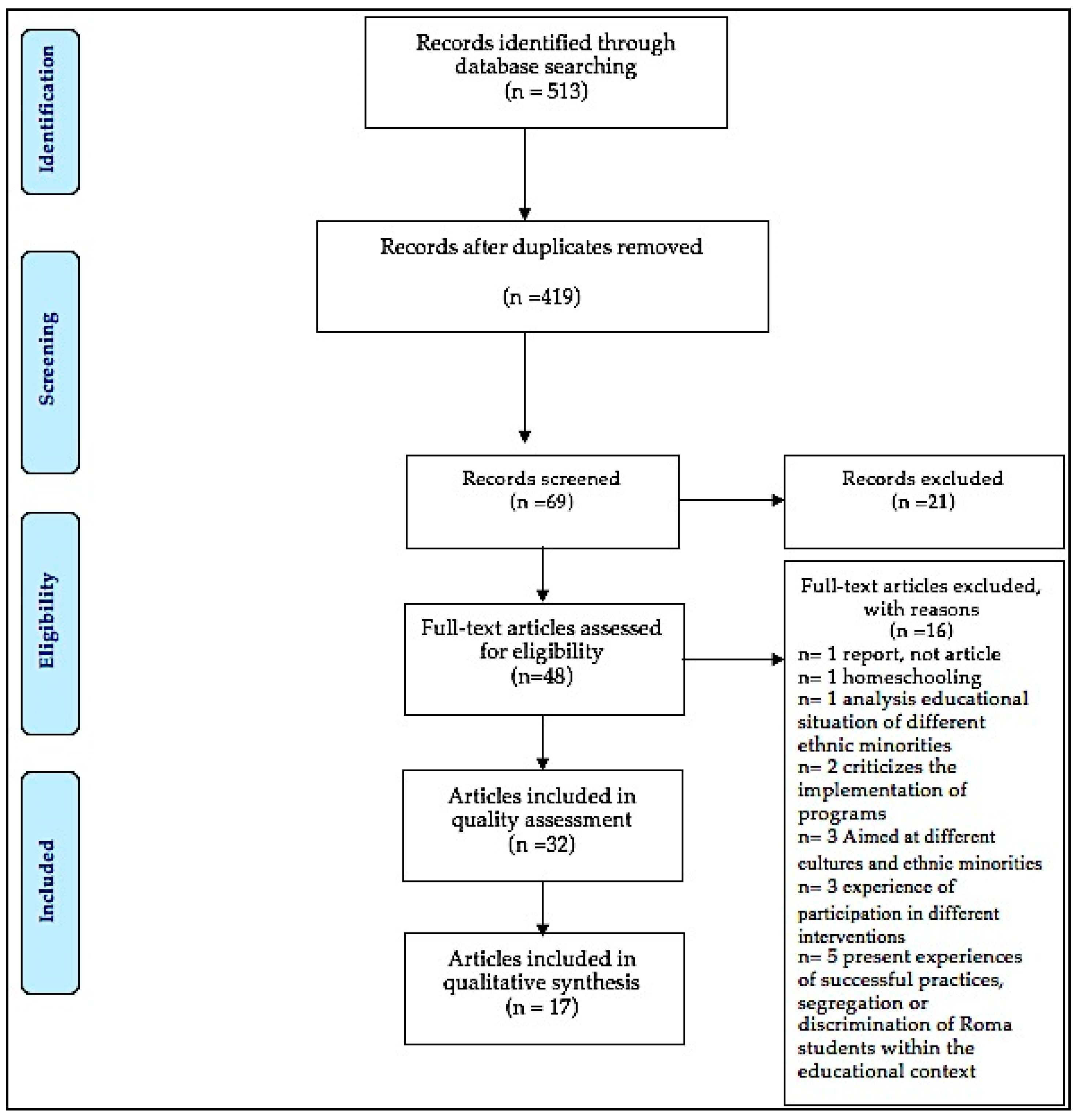

2.1. Selection Procedure and Datamining

2.2. Criteria for Inclusion of Articles

3. Results

3.1. Studies Carried out at School

3.2. Studies Carried out in the Extracurricular Context

3.3. Studies Carried out in the Community Context

3.4. Studies Conducted in More Than One Context

3.5. Summary of Studies

4. Discussion and Conclusions

5. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Reference | [29] |

| Background | Pilot program in nutrition education, designed as a community intervention. It was developed in the framework of social learning theory and self-empowerment. Three ways considered action: class, a workshop and cafeteria, as well as a plan for the families of students. |

| Objectives | To promote healthy eating habits, along with the development of skills and self-empowerment |

| Beneficiary | 150 children (8–12 years, 80% Roma) identified a school in a deprived area of Bilbao, Spain. |

| Context | School |

| School level | 3rd–6th Primary E.; 1st Secondary E. |

| Main results | After two years, the program evaluation showed improvements in knowledge, skills and behavior of children. The qualitative evaluation showed a positive attitude in the program. The involvement of families in the meetings was low, dental hygiene showed little improvement. |

| Reference | [39] |

| Background | Learney school program that promotes inclusion, addressing underachievement and high dropout rates. It organizes activities and helps children to finish Primary education. Various teaching methods are identified. |

| Objectives | To provide time and space for Roma children to carry out after school activities. |

| Beneficiary | Children and youth (6 to 18 years) in Hungary |

| Context | Extracurricular |

| School level | Primary E. and Secondary E. |

| Main results | The case study shows, no results of interventions. |

| Reference | [30] |

| Background | Intercultural Education experience to solve problems of racism and relationships experienced by young Roma when attempting to integrate school. |

| Objectives | To develop tolerance and reduce prejudice towards Roma culture. To create an environment that fosters relationships of respect. |

| Beneficiary | 16 students (17–23 years, 25% Gypsies), the course of social guarantee of IES, Orcasitas area, Madrid, Spain |

| Context | Classroom-workshop. |

| School level | Secondary E. |

| Main results | The interviews showed a change in valuation among students. Questionnaires are increased in the provision for work and respect for Roma culture. Positive change of attitudes, (classwork and relationship with peers) are witnessed |

| Reference | [44] |

| Background | The article presents the three main phases of the In-Service Training for Roma Inclusion (INSETRom) Project. It discloses the main activities and results of the three phases proposed in the project (needs assessment, curriculum development and teacher training, implementation and evaluation of interventions) |

| Objectives | To promote educational inclusion, improving the effectiveness of teachers in their schooling, strengthening the relationship between community and school. |

| Beneficiary | Roma students (7–10%), between 5 and 14 years, teachers and parents from three schools (primary, secondary and special) in Vienna, Austria. |

| Context | College Extracurricular |

| School level | Primary E., Secondary E. and Special E. |

| Main results | The results of the teaching are presented. They indicate that in the implementation phase training has led to changes in practices and teaching methods, improving skills in the daily work with Roma students, and a better relationship between family and school is evident. |

| Reference | [45] |

| Background | The article presents the results of EU-funded INSETR It focuses on the needs assessment phase of the entire community, and on the implementation of the training program for teachers. |

| Objectives | To promote inclusive education in schools in Cyprus and to identify the needs of the educational community for interventions. |

| Beneficiary | Three schools (urban primary, secondary and rural primary) with 62 Roma students in total, in Cyprus. |

| Context | College Extracurricular |

| School level | Primary E. and Secondary E. |

| Main results | Teachers showed pessimism about the results of training and implementation in teaching Roma students. The results show that educational inclusion strategies should be comprehensive, and also that there should be a greater focus on interculturalism. |

| Reference | [31] |

| Background | Intervention program aimed at Roma students of Secondary Education. Through action research, the center’s needs are identified and a, plan of action for two academic cycles is developed by the educational community leading the group of students in compensatory education. |

| Objectives | To design, develop and evaluate an intervention inclusive program for students, teachers and also for the school. |

| Beneficiary | Eighteen Roma students and mixing mixed raced students (Spanish, Roma) of a group of compensatory educations, Secondary Education Institute. |

| Context | School |

| School level | 1st. Secondary Education (compensatory education). |

| Main results | The article presents the results of the first year of intervention and improvement proposal for the second. It also presents Increased educational expectations from the tutor. Evidence shows students’ better self-esteem, motivation, better grade decrease in disciplinary, action from part of the teachers, greater integration into school activities and decreased absenteeism. |

| Reference | [3] |

| Background | The Roma Teaching Assistant Program, focuses on an inclusive and multicultural school. Inclusive classrooms were designed, which included aspects of Roma culture that are integrated to teaching methodologies. Roma teaching assistants for Roma children resulted in improved communication amongst all. |

| Objectives | To promote inclusion and the adaptation of Roma students to the education system. |

| Beneficiary | Fifty students from the ages to 5 and 7 from 9 different classrooms in Latvia. |

| Context | School |

| School level | Child E. and Primary E. |

| Main results | All Roma students were able to successfully integrate the school displaying evident social and academic growth. |

| Reference | [32] |

| Background | Teaching laboratory experiments is a strategy of learning to increase motivation of Roma students. Assigning an active role to the student, increases their interest and gives control over the learning process. Issues of ecology and environmental protection were selected. |

| Objectives | To increase the quality and quantity of knowledge, and motivation of Roma school students. |

| Beneficiary | Two hundred and thirty-two students (9–10 years, 21.55% Roma) of primary schools in 4 different cities and villages in Serbia. |

| Context | School lab |

| School level | 3rd Primary E. |

| Main results | Initial tests and final results display an improvement 2.17 times higher than in non-Roma students, thus increasing the ecological laboratory quality, quantity of knowledge, and motivation Roma students. Roma children expressed their satisfaction with the work developed and interest in continuing these projects. |

| Reference | [33] |

| Background | The intervention is a longitudinal case study of 4 years (2006–2010), which is part of the integrated INCLUD-ED (European Commission VI) EU-funded project. Through the dialogic learning, different activities involving the participation of Roma families in decision-making activities and school to improve children’s learning were established. |

| Objectives | Implement Successful Educational Actions (SEAs). Establish a dialogic and participatory process among all the educational community. |

| Beneficiary | College students and families La Paz, Albacete, Spain. |

| Context | School |

| School level | Primary E. and Secondary E. |

| Main results | The implementation of SEAs has contributed to academic success and reversing situations of inequality. Performance improvements of national standardized tests and increased educational opportunities at school are observed. School absenteeism rates were reduced and an increase in the enrollment percentage of new students was observed. |

| Reference | [34] |

| Background | Project by the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and funded by the EU, aimed at young Roma students. A case study related to the importance and use of information technology in delivering new media in the Roma popular culture is presented. |

| Objectives | To involve Roma students in the production of knowledge through the use of new technological means. To create a sense of identity and promote their participation through cultural elements. |

| Beneficiary | Students in a class support (13 and 15) in a high school in the city of Thessaloniki (Greece). |

| Context | School |

| School level | Secondary E. |

| Main results | Participation and motivation evidenced by students in the different tasks of the project; however, the use of digital technology was not a valid knowledge. The importance of effective methods in teaching Roma students noted. Digital technology helped students overcome Roma obstacles related to written language, therefore, they managed to express themselves more creatively bringing down barriers. |

| Reference | [35] |

| Background | Programs developed by the Center for Media Research in Education (Eotvos Lorand University, Hungary) affiliated to UNESCO (2005–2013). It was based on collaboration between teachers and families. Developing interdisciplinary programs supported Information Technology and Communication (ICT), trialogical learning theory, art, science and mathematics. They also supported students then in high school. |

| Objectives | To improve motivation and to effectively improve social skills, verbal and visual communication as well as promoting earning achievements. |

| Beneficiary | Roma multigrade school students from small towns in Hungary. |

| Context | multigrade schools |

| School level | Primary E. |

| Main results | Learning achievements show that, through motivating teaching methods, Roma students are able to learn mathematics and other disciplines. The use of ICT turned out to be a methodology that facilitated access to teaching and learning. |

| Reference | [46] |

| Background | Education for All (formerly assistant teaching Roma) is one of the major interventions in Southeast Europe since 2009 is administered by the Ministry of Education of Serbia. The strategy of a Roma assistant (teaching assistant) per school is used to support the education of children and strengthen the relationship between family and school. |

| Objectives | The objective of this article is to describe general aspects of the program and assess their impact in the first year of implementation. |

| Beneficiary | The program is aimed at students Roma primary school students and also Serbian students, as well as families and Roma community. |

| Context | School, out of school and community |

| School level | Primary E. |

| Main results | The results are evaluated in relation to grades in mathematics, Serbian and the number of hours of absence in a year, of Roma children. A greater program impact is evident in schools with fewer Roma children; however, an average positive effect was achieved. Absences were reduced and grades were improved. |

| Reference | [40] |

| Background | Program to promote school engagement (behavioral and cognitive) of Roma students through storytelling (Sarilhos do Amarelo [41]) |

| Objectives | To promote school engagement and to improve participation and motivation. |

| Beneficiary | 35 Roma children (10–12 years) two primary schools in Braga, Portugal. |

| Context | Extracurricular |

| School level | 4th Primary E. |

| Main results | Their results highlight the effectiveness of the program to improve school commitment from part of Roma students. Results have shown that with appropriate strategies and methodologies greater school engagement can be achieved in this group. |

| Reference | [42] |

| Background | Knock, knock It’s time to learn! is a 4 year intervention to promote behavioral commitment (truancy and classroom behavior) and school performance of Roma children. For 4 years, the research assistant, according to a structured protocol, knocked on the door of the children in the experimental group to invite them to school. |

| Objectives | To increase school attendance, better behavior, performance in mathematics and school progression rate. To inform interventions that have a positive influence on school engagement. |

| Beneficiary | Thirty Roma children (6 to 11 years), a city north of Portugal (16 children experimental and 14 control). |

| Context | Community |

| School level | It begins in year 1st. and ends in year of Primary E. |

| Main results | The results of the experimental group demonstrate the effectiveness of intervention in promoting behavioral commitment amongst Roma students. Children improved attendance, behavior, and had higher grades in math, increasing their school progress. The importance of the neighborhood and the social environment awareness, where their culture. Is valued play a vital role. |

| Reference | [43] |

| Background | Reclaiming Adolescence, the project, developed with three collaborating institutions. They use participatory action-research youth. The project prepared for young Roma and non-Roma, to become researchers. Through training and adequate preparation, young people were involved in the design and implementation of research and the resulting community actions. |

| Objectives | Information on educational and professional opportunities of young Roma. To Strengthen the capacity of young researchers to benefit their community. To Develop research strategies following the suggestions of young people. |

| Beneficiary | Twenty young people from 15 to 24 years (55% Roma) in Zvezdara and Palilula, Belgrade (Serbia) |

| Context | Community |

| School level | Secondary E. and University |

| Main results | Through the project young researchers were able to develop different skills and knowledge, including leadership, communication, civic, ethnic identity, self-esteem, critical thinking. In addition to a strong commitment to social justice and equity, they also learned about the importance of design education and small-scale projects within their communities. |

| Reference | [36] |

| Background | Music Workshop was conducted with the collaboration of the University of Uludağ and the Roma Association of Central Bursa. Choral education in the context of music education was developed in order, to strengthen the personality, socialization processes and musical and communicative abilities of Roma students. |

| Objectives | To establish a music workshop at school with Roma children |

| Beneficiary | Thirty-two Roma children (100% Roma) of a primary school in Mustafakemalpaşa, Bursa (Turkey) |

| Context | School |

| School level | 4th Primary E. |

| Main results | The case study results have shown that music education should occupy an important place in education of Roma students as it plays an important role in their social and cultural background. In addition, an increase in communication musical skills, and peer relationships was seen. A sense of belonging and school motivation, increased school attendance and cultural awareness were also witnessed. |

| Reference | [37] |

| Background | Increscendo project of intercultural education and collaborative, based on the musical training is based on experiences in similar social contexts. |

| Objectives | To generate attitudes and promote intercultural values and personal identity |

| Beneficiary | 40 students (58% Roma) School “Antonio Allúe Morer”, Valladolid, Spain. |

| Context | School |

| School level | 2nd–6th E. Primary E. and 1st.Secondary E. |

| Main results | The process of social and educational inclusion is encouraged, moving towards intercultural education and development. The results have also identified the development of values, attitudes and knowledge. |

References

- Santos, M. Migraciones, Sostenibilidad y Educación. Revista de Educación 2009, Número Extraordinario, Educar para el Desarrollo Sostenible. 2009, pp. 123–145. Available online: http://www.revistaeducacion.mec.es/re2009/re2009_06.pdf (assessed on 15 February 2019).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission. Europe 2020. A Strategy for Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth. 2020 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2010; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Zaķe, D. Qualitative education for roma students: A pedagogical model for sustainable development. J. Teach. Educ. Sustain. 2010, 12, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J.A. Multicultural Education: Development, Dimensions and Challenges. Phi Delta Kappan 1993, 75, 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, M. Sostenibilidad y educación intercultural. El cambio de perspectiva. Bordon 2011, 63, 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Leskova, L. The social exclusión of romaníes and the strategies for coping with this problema. Clin. Soc. Work 2014, 5, 44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Abajo, J.E. La escolarización de los niños gitanos (o la educación como proceso interpersonal que refleja y reproduce relaciones sociales desiguales y contradictorias). Cultura y Educación: Revista de Teoría Investigación y Práctica 1996, 8, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Nions, H. Different and unequal: The educational segregation of Roma pupils in Europe. Intercult. Educ. 2010, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Carrión, R.; Molina-Luque, F.; Molina, S. How do vulnerable youth complete secondary education? The key role families and the community. J. Youth Stud. 2017, 21, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Europea. Comunicación de la Comisión al Parlamento Europeo y al Consejo. Revisión Intermedia del Marco Europeo de Estrategias Nacionales de Integración de los Gitanos; Comisión Europea: Brussels, Belgium, 2017; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. Roma Survey—Data in Focus Education: The Situation of Roma in 11 EU Member States; FRA: Viena, Austria, 2014; pp. 1–68.

- Antúnez, Á.; Núñez, J.C.; Burguera, J.L.; Rosário, P. Variables affecting academic performance, achievement, and persistence of Roma students. In Factors Affecting Academic Performance; González-Pineda, J.A., Bernardo, A., Núñez, J.C., Rodriguez, C., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 191–218. [Google Scholar]

- Open Society Institute. 10 Goals for Improving Access to Education for Roma; EU Monitoring and Advocacy Program Education Support Program Roma Initiatives: Brussels, Belgium, 2009; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kılıçoğlu, G.; Kılıçoğlu, D.Y. The Romany States of Education in Turkey: A Qualitative Study. Urban Rev. 2018, 50, 402–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, M.; Bhopal, K. Gypsy, Roma and Traveller children in schools: Understandings of community and safety. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 2009, 57, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Tackling Early School Leaving: A Key Contribution to the Europe 2020 Agenda; COM18 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ryder, A. One nation conservatism: A Gypsy, Roma and Traveller case study. Race Class 2015, 57, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regadera, J.; Pérez-Herrero, M.; Burguera, J. Variables socioemocionales y rendimiento académico en seis alumnos gitanos de educación primaria. In La crisis social y el Estado del Bienestar: Las Respuestas de la Pedagogía Social; Torío, S., García-Pérez, O., Peña, J.V., Fernández, C.M., Eds.; Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Oviedo: Gijón, Spain, 2013; pp. 329–333. [Google Scholar]

- Garreta, J. La atención a la diversidad cultural en Cataluña: Exclusión, segregación e interculturalidad. Rev. Educ. 2011, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byram, M.; Perugini, D.C.; Wagner, M. The development of intercultural citizenship in the elementary school Spanish classroom. Learn. Lang. 2013, 18, 16–31. [Google Scholar]

- GUÍA INTER. Una guía para Aplicar la Educación Intercultural en la Escuela. Proyecto INTER; UNED: Madrid, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jordán, J.A. ¿Qué educación intercultural para nuestra escuela? 2010, 1–21. Available online: http:www.aulaintercultural.org (assessed on 10 February 2019).

- Sales, A.; García, R. Educación intercultural y formación de actitudes. Programa pedagógico para desarrollar actitudes interculturales. Revista Española de Pedagogía 1997, 207, 317–336. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Gámez, R.; Goenechea, C. Educación para una Ciudadanía Intercultural; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2015; pp. 1–243. [Google Scholar]

- Soriano, A. Convivir entre culturas: Un compromiso educativo. In Educación para la Convivencia Intercultural; Soriano, E., Ed.; La Muralla, S.A.: Madrid, Spain, 2007; pp. 99–126. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz Sedano, A. Enfoques y modelos de educación multicultural e intercultural. In Perspectivas Teóricas y Metodológicas: Lengua de Acogida, Educación Intercultural y Contextos Inclusivos; Reyzabal, Mª.V., Ed.; Dirección General de Promoción Educativa: Madrid, Spain, 2003; pp. 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Aguaded, E. Diagnóstico Basado en el Currículo Intercultural de Aulas Multiculturales en Educación Obligatoria. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Granada, Granada, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Rodrigo, C.; Aranceta, J. Nutrition education for schoolchildren living in a low-income urban area in Spain. J. Nutr. Educ. 1997, 29, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araque, N. Experience on conflict resolution across cultures through a classroom-workshop on Intercultural Education. Revista Complutense de Educación 2009, 20, 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Iguacel, S.; Buendía, L. Evaluación de un programa para la mejora de un aula de educación compensatoria desde un enfoque inclusivo. Bordón Revista de Pedagogía 2010, 62, 127–135. [Google Scholar]

- Adamov, J.; Segedinac, M.; Kovic, M.; Olic, S.; Horvat, S. Laboratory Experiment as a Motivational Factor to Learn in Roma Elementary School Children. Stanisław Juszczyk 2012, 28, 153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Flecha, R.; Soler, M. Turning difficulties into possibilities: Engaging Roma families and students in school through dialogic learning. Camb. J. Educ. 2013, 43, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangoulidou, F. Using new media in teaching Greek Roma students. CLCWeb Comp. Lit. Cult. 2013, 15, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kárpáti, A.; Molnár, É.D.; Munkácsy, K. Pedagogising Knowledge in Multigrade Roma Schools: Potentials and tensions of innovation. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2014, 13, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gül, G.; Eren, B. The Effect of Chorus Education in Disadvantageous Groups on the Process of General Education—Cultural Awareness and Socializing: The Sample of Gypsy Children. J. Educ. Learn. 2018, 7, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio Gervas, J.M.; Leon Guerrero, M.M. Music as a model of social inclusion in educational spaces with gypsys and inmigrants students. Revista Complutense de Educación 2018, 29, 1091–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byram, M.; Wagner, M. Making a difference: Language teaching for intercultural and international dialogue. For. Lang. Ann. 2018, 51, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messing, V. Good practices addressing school integration of Roma/Gypsy children in Hungary. Intercult. Educ. 2008, 19, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, P.; Núñez, J.C.; Vallejo, G.; Cunha, J.; Azevedo, R.; Pereira, R.; Nunes, A.; Fuentes, S.; Moreira, T. Promoting Gypsy children school engagement: A story-tool project to enhance self-regulated learning. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 47, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, P.; Núñez, J.; González-Pienda, J. Projecto Sarilhos do Amarelo: Auto-Regulação em Crianças sub-10; Porto Editora: Porto, Portugal, 2007; pp. 1–108. [Google Scholar]

- Rosário, P.; Núñez, J.C.; Vallejo, G.; Azevedo, R.; Pereira, R.; Moreira, T.; Fuentes, S.; Valle, A. Promoting Gypsy children’s behavioural engagement and school success: Evidence from a four-wave longitudinal study. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2017, 43, 554–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhabha, J.; Fuller, A.; Matache, M.; Vranješević, J.; Chernoff, M.C.; Spasić, B.; Ivanis, J. Reclaiming adolescence: A Roma youth perspective. Harv. Educ. Rev. 2017, 87, 186–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciak, M.; Liegl, B. Fostering Roma students’ educational inclusion: A missing part in teacher education. Intercult. Educ. 2009, 20, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symeou, L.; Karagiorgi, Y.; Roussounidou, E.; Kaloyirou, C. Roma and their education in Cyprus: Reflections on INSETRom teacher training for Roma inclusion. Intercult. Educ. 2009, 20, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, M.; Lebedinski, L. Equal access to education: An evaluation of the Roma teaching assistant program in Serbia. World Dev. 2015, 76, 62–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladson-Billings, G. But That’s Just Good Teaching! The Case for Culturally Relevant Pedagogy. Theory Pract. 1995, 34, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCloskey, S. Are We Changing the World? Reflections on Development Education, Activism and Social Change. Policy Pract. Dev. Educ. Rev. 2016, 22, 110–130. [Google Scholar]

- Matache, M. Biased elites, unfit policies: Reflections on the lacunae of Roma integration strategies. Eur. Rev. 2017, 25, 588–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüggemann, C. Romani culture and academic success: Argument against the belief in a contradiction. Intercult. Educ. 2014, 25, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Open Society Institute. Roma Children in “Special Education” in Serbia: Overrepresentation, Underachievement, and Impact on Life; Open Society Institute: Budapest, Hungary, 2010; pp. 1–194. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfields, M.; Ryder, A. Research with and for Gypsies, Roma and Travellers: Combining policy, practice and community in action research. In Gypsies and Travelers: Empowerment and Inclusion in Society; Richardson, J., Tsang, A., Eds.; The Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2012; pp. 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasutti, M.; Concina, E.; Frate, S. Working in the classroom with migrant and refugee students: The practices and needs of Italian primary and middle school teachers. Pedag. Cult. Soc. 2019, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfields, M.; Home, R. Assessing Gypsies and Travellers needs: Partnership working and “The Cambrige Project”. Romani Stud. 2006, 16, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marc, A.; Bercus, C. The Roma education fund: A new tool for Roma inclusion. Eur. Educ. 2007, 39, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goenechea, C. ¿Es la formación del profesorado la clave de la Educación intercultural? Revista Española de Pedagogía 2008, 239, 119–136. [Google Scholar]

- Byram, M. Twenty-five years on—From cultural studies to intercultural citizenship. Lang. Cult. Curric. 2014, 27, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasutti, M.; Concina, E.; Frate, S. Social sustainability and professional development: Assessing a training course on intercultural education for insevice teachers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations). Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/es/gender-equality/ (accessed on 24 April 2019).

- Duke, N.; Borowsky, I.; Pettingell, S. Adult perceptions of neighborhood: Links to youth engagement. Youth Soc. 2012, 44, 408–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Search Criteria | Scopus | WOS | ERIC | Duplicates | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial search | 399 (50.95) | 283 (36.14) | 101 (12.89) | 783 (100) | |

| Inclusion criteria (1) * | 216 (42.1) | 229 (44.63) | 68 (13.25) | 513 (100) | |

| Inclusion criteria (2) ** | 28 (40.57) | 25 (36.23) | 10 (14.49) | 6 (8.69) | 69 (100) |

| Inclusion criteria (3) *** | 2 (11.76) | 8 (47.05) | 1 (5.88) | 6 (35.29) | 17 (100) |

| Database | Scopus-Eric | Scopus-WOS | Wos-ERIC | Scopus-Wos-ERIC | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duplicate items | 13 (13) | 58 (61.7) | 3 (3.19) | 20 (21.27) | 94 (100) |

| Quantity | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Context | ||

| School | 10 | 58.82 |

| Extracurricular | 2 | 11.76 |

| Community | 2 | 11.76 |

| More than one context | 3 | 17.64 |

| Total | 17 | 100 |

| School level | ||

| More than one level | 9 | 52.94 |

| Primary | 5 | 29.41 |

| Secondary | 3 | 17.64 |

| Total | 17 | 100 |

| Recipients | ||

| Only Roma students | 5 | 29.41 |

| Roma and non-Roma students | 12 | 70.58 |

| Total | 17 | 100 |

| Country where the program or procedure is performed | ||

| Spain | 5 | 29.41 |

| Serbia | 3 | 17.64 |

| Portugal | 2 | 11.76 |

| Hungary | 2 | 11.76 |

| Cyprus | 1 | 5.88 |

| Greece | 1 | 5.88 |

| Austria | 1 | 5.88 |

| Latvia | 1 | 5.88 |

| Turkey | 1 | 5.88 |

| Total | 17 | 100 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salgado-Orellana, N.; Berrocal de Luna, E.; Sánchez-Núñez, C.A. Intercultural Education for Sustainability in the Educational Interventions Targeting the Roma Student: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3238. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123238

Salgado-Orellana N, Berrocal de Luna E, Sánchez-Núñez CA. Intercultural Education for Sustainability in the Educational Interventions Targeting the Roma Student: A Systematic Review. Sustainability. 2019; 11(12):3238. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123238

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalgado-Orellana, Norma, Emilio Berrocal de Luna, and Christian Alexis Sánchez-Núñez. 2019. "Intercultural Education for Sustainability in the Educational Interventions Targeting the Roma Student: A Systematic Review" Sustainability 11, no. 12: 3238. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123238

APA StyleSalgado-Orellana, N., Berrocal de Luna, E., & Sánchez-Núñez, C. A. (2019). Intercultural Education for Sustainability in the Educational Interventions Targeting the Roma Student: A Systematic Review. Sustainability, 11(12), 3238. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123238