Abstract

Meat analogs are processed foods designed to mimic meat products. Their popularity is increasing among people seeking foods that are healthy and sustainable. Animal-sourced protein products differ in both their environmental impact and nutritional composition. The protein sources to produce meat analogs come from different plants. There is a lack of published research data assessing differences in these two aspects of meat analogs according to the plant protein source. This study compared the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of different types of meat analogs according to their main source of protein (wheat, soy, wheat and soy, or nuts), and their nutritional composition. We also compared totally plant-based products with those containing egg. We performed life cycle analyses of 56 meat analogs from ingredient production to the final commercial product. The nutrient profile of the meat analogs was analyzed based on ingredients. Descriptive statistics and differences between means were assessed through t-test and ANOVA. No differences in GHG emissions were observed among products with different major sources of protein. However, egg-containing products produced significantly higher amounts of GHG (p < 0.05). The nutritional composition of all meat analogs was found to be quite similar. Altogether, total plant-based meat analogs should be the choice for the sake of the environment.

1. Introduction

People and planetary health are clearly interconnected. Human health is directly affected by the quantity and the quality of foods that we consume [1,2,3]. Climate and environmental changes have impacted food production by decreasing agricultural yields and increasing food insecurity and water scarcity in some regions of the world [4,5]. It should be noted, however, that one of the major forces of these changes in the ecosystems is the food chain. Around 30% of the total anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and 70% of fresh water usage are from the food sector [6]. The food sector is also one of the leading causes of land use change and loss of biodiversity [7]. Moving to a more sustainable agriculture technology and reducing food losses have been proposed to address this issue. However, these measures are not enough. A change in dietary habits at the population level is necessary [8,9,10,11,12].

Comparing different strategies aimed at modifying global dietary patterns to improve human and planetary health, such as reducing the consumption of animal-sourced products and lowering caloric intake, the former has been suggested as the most effective strategy [13]. Well-planned plant-based diets have been recognized as nutritionally adequate, and appropriate for human growth and development. Such diets are suitable not only in the prevention but also in the treatment of many chronic diseases [14,15,16]. Diets rich in plant-based products and low in animal-sourced foods are associated with lower risks for diseases such as type 2 diabetes, obesity, cancer, and coronary heart disease, as well as a greater life-expectancy [17,18,19]. At the same time, plant-based diets are more environmentally friendly. They are typically associated with considerably less GHG emissions compared with that of meat-based diets [20,21]. This is primarily because the production of animal-derived foods, especially beef, generate a bigger carbon footprint than the production of plant foods [22]. In fact, among those who consume animal-based products, these foods are the major contributors to the carbon footprint of their diets [23].

The adoption of plant-based diets could be difficult for some people. Various barriers exist, such as the enjoyment of meat or the difficulty of changing established cultural eating habits [24,25,26]. The options available to people in making the shift must be acceptable on a personal, nutritional, financial, and environmental basis. The World Watch Institute has proposed meat analogs as viable lower carbon footprint alternatives to processed meat products [27]. Meat analogs are processed convenience foods, rich in protein, that are prepared to resemble meat in texture and appearance [28]. In addition, they are often flavored to smell and taste like chicken, beef, turkey, or fish. Over the past decade, there has been an increased use of a number of meat analogs that are marketed and sold as protein-rich substitutes for meat [28,29]. More than one third of Americans have reported purchasing meat analogs at some time [30]. In addition to their popularity among vegetarians, the meat analogs are also consumed by non-vegetarians who wish to cut back on meat, and who choose them as a healthy alternative or as part of a more environmentally friendly diet [31].

A few publications have focused on the assessment of the carbon footprint of meat analogs [32,33,34,35,36]. All concluded that meat analogs are a more sustainable alternative to meat and processed meat products. In addition, many meat analogs qualify as complete proteins and also contain substantial levels of dietary fiber, natural antioxidants and phytochemicals, while possessing a low saturated fatty acid content and no cholesterol [16,37]. Meat analogs are typically formulated from wheat or soy protein, but may also contain mycoprotein, nuts, legumes and/or vegetables [29]. Some may also contain animal-sourced ingredients such as egg or milk. People may choose to avoid specific types of meat analogs for different reasons, such as food allergies/intolerances (i.e., celiac disease, soy and nut allergies) or to follow a specific type of dietary pattern (e.g., gluten-free or vegan diets). Meat analogs are mainly consumed by health-conscious individuals, who are often aware of the sustainability of their diet [31]. Variation in sustainability and nutritional composition among these products could be a factor in consumer choices. It is known that different types of animal-sourced protein foods (e.g., chicken, pork, and beef) differ in both their environmental impact and nutritional composition [22,37]. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, beef consumption peaked in the mid-1970s, while chicken consumption has doubled since that time [38]. This change in eating habits is due in large part to the increased awareness of the effects of red meat consumption upon one’s health [39]. There is a lack of published research assessing the environmental impact and nutritional value of meat analogs derived from different protein sources. As was the case for animal-based protein, this knowledge could be used for a more conscious decision when opting for specific meat analogs.

Therefore, we compared the GHG emissions derived from the production of different types of meat analogs according to their main protein source, and their nutritional composition. Additionally, we also compared totally plant-based meat analogs with those containing egg.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Assessed Products

The production of the meat analogs considered in this study have been reported elsewhere [35]. In brief, we had access to up-to-date primary data for 56 commonly consumed meat analogs. The data was collected from three different food factories specializing in making meat analogs. Each factory developed data inventories with information about all the inputs (including raw ingredients) and outputs required to produce their commercial recipes.

2.2. Data for GHG Emissions of Meat Analog Products

Mejia et al. [35] described the assessment of GHG emissions for the meat analogs. Briefly, a life cycle assessment (LCA) was performed on the data collected. LCA is a quantitative method that shows the impact of a process, such as food production and manufacturing, on the environment [40,41,42]. The LCA calculation covered inputs from the farm (including the production of raw material) to the factory exit gate (including the packaged product ready to ship for retail sale). Hence, the LCA assessed growing the raw ingredients (wheat, beans, vegetables, nuts, spices, etc.), transporting these products from the farm to the factory, processing the ingredients into meat analogs, and packaging the final products. SimaPro 8.5 [43], a LCA software tool, allows the assessment of the emissions from materials and the energy inputs throughout the life cycle of a product. Using our LCA data and SimaPro 8.5 database (Ecoinvent 3.4 and US Life Cycle Inventory database), calculations were performed for the emission of gases with potential global warming, such as carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O), using a pre-programmed algorithm (Impact 2002+) [44]: 1 kg of CO2 equals 1 kg of carbon dioxide equivalents (CO2e), 1 kg of CH4 equals 25 kg of CO2e and 1 kg of N2O equals 298 kg of CO2e.

GHG emission data were calculated as kg of CO2e per 100 g of product, also per 20 g of protein and per 100 kcal.

2.3. Nutritional Value of Meat Analog Products

The ingredients for every product batch for the 56 meat analogs were provided by each factory. The nutritional value of the meat analogs was analyzed according to their ingredient composition. We used the Nutrition Data System for Research 2013 database, which contains more than 20,000 foods that are annually updated while maintaining nutrient profiles true to the version used for data collection [45]. The nutritional values were calculated per 100 g of product.

2.4. Classification of Meat Analog Products

We classified the meat analogs according to their main source of protein: wheat-based products (containing at least 65% wheat); soy-based products (containing at least 65% soy); wheat/soy-based products (in which both wheat and soy were below 65%); and nut-based products (containing nuts, beans and/or vegetables). Wheat-based, soy-based and wheat/soy-based products did not contain nuts, any non-soy legume, or vegetables. The meat analogs were also analyzed either as total plant-based products or those containing egg.

Statistical tests used in comparing groups included the 2-sample t-test and ANOVA, followed by Tukey adjustment. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. GHG Emissions of Meat Analog Products

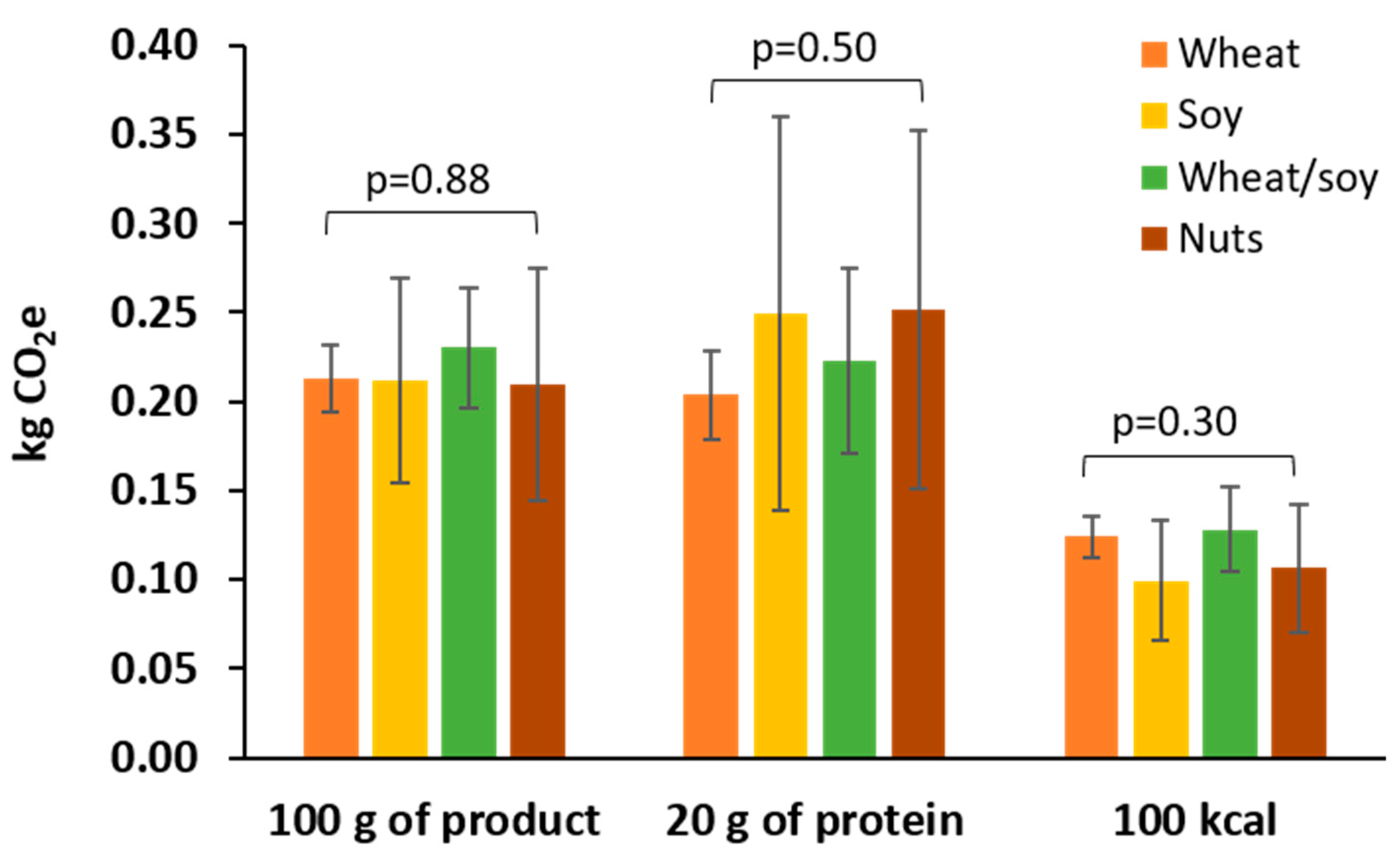

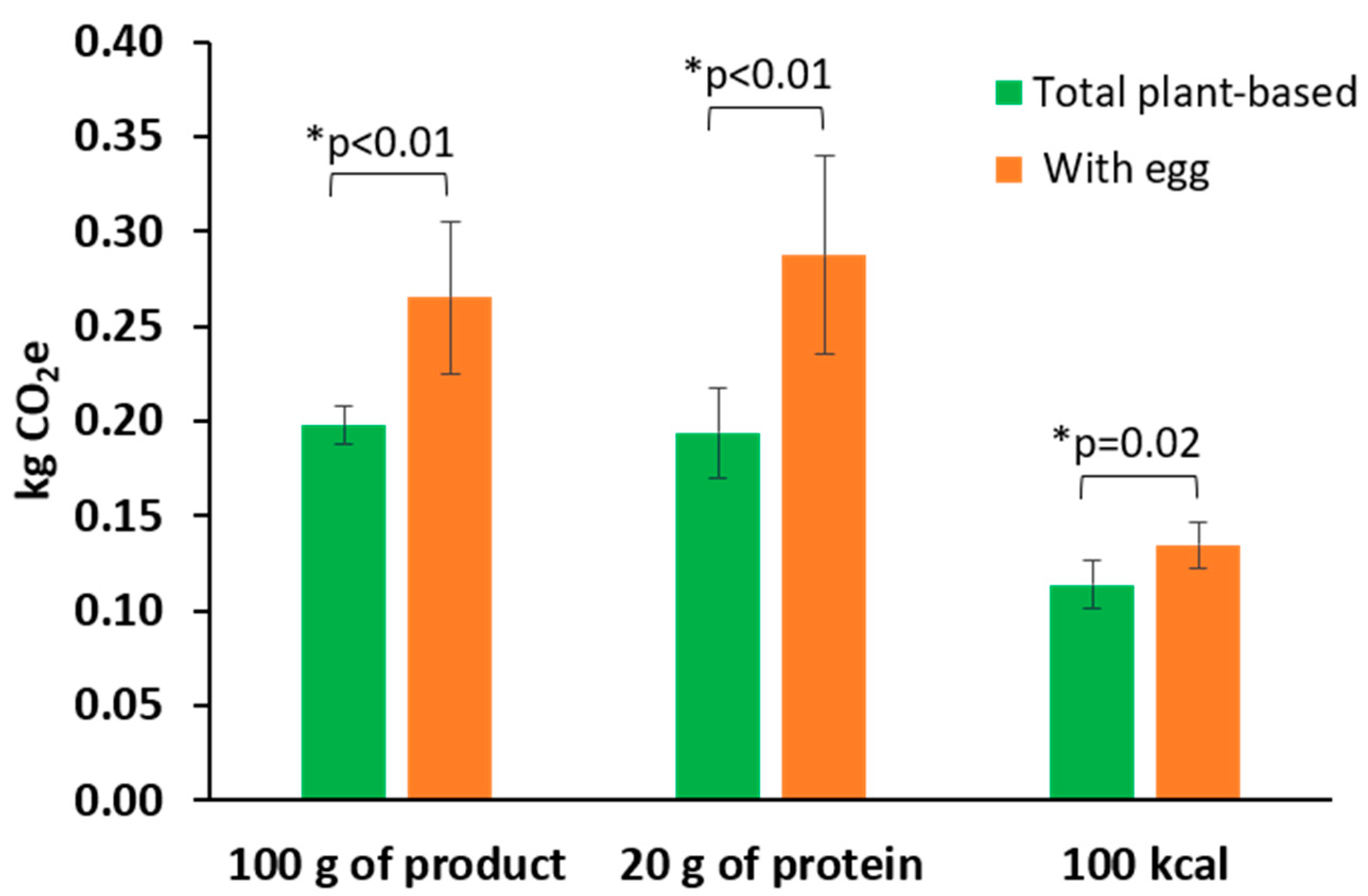

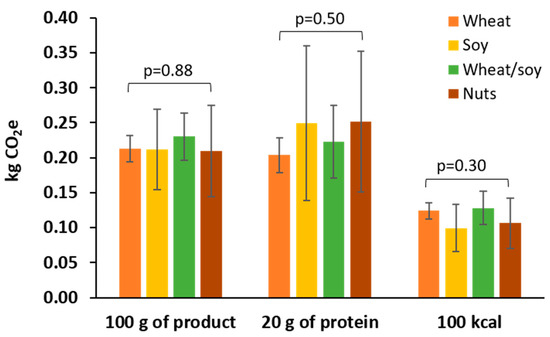

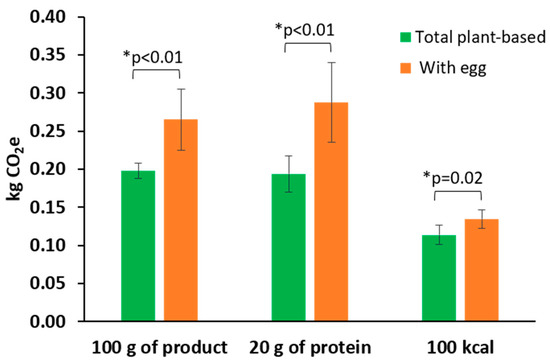

GHG emission data was remarkably similar for meat analogs irrespective of their main source of protein (Figure 1). The mean GHG emissions for wheat-based products was 0.21 kg CO2e per 100 g, for soy-based products 0.21 kg CO2e per 100 g, for wheat/soy-based products 0.23 kg CO2e per 100 g, and for nuts-based products 0.21 kg CO2e per 100 g (p = 0.88). No differences were found between the analogs based on either protein content (p = 0.50) or caloric content (p = 0.30). The presence of egg in the meat analogs increased the GHG emissions significantly from 0.20 kg CO2e (total plant-based products) to 0.27 kg CO2e (analogs with egg), per 100 g product (p < 0.01) (Figure 2). Similar results were seen with data expressed per 20 g of protein (p < 0.01) or per 100 kcal (p = 0.02). Table S1 of the Supplementary Material shows the GHG emissions (mean, SD and range values) for all 56 meat analogs classified by main source of protein and the presence of animal-sourced ingredients.

Figure 1.

Greenhouse gas emissions (kg CO2e: mean and 95% Confidence Interval) of different types of meat analog products according to their main source of protein. CO2e: CO2 equivalents. Differences between means assessed through ANOVA, followed by Tukey adjustment. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. No statistical difference was observed in any comparison.

Figure 2.

Greenhouse gas emissions (kg CO2e: mean and 95% Confidence Interval) of meat analog products total plant-based and containing egg. CO2e: CO2 equivalents. Differences between means assessed through 2-sample t-test. * p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3.2. Nutritional Value of Meat Analog Products

According to Table 1, there are no major differences according to the content of protein, polyunsaturated fatty acids, cholesterol, sodium, vitamin A and vitamin B12 among meat analogs which differ in their main source of protein (p > 0.05). When compared with the other meat analogs, the soy-based analogs contained more energy, had higher levels of fiber and omega-3 fatty acids, as well as greater amounts of the micronutrients iron, zinc, vitamins B1, B2, B6 and folic acid. The nut-based analogs were higher in total fat, monounsaturated fat and niacin. The nutrient profile of total plant-based analogs was no different from that of the analogs containing egg, with the exception that the egg-containing analogs had higher levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids and vitamin A (Table 2).

Table 1.

Nutritional value of different type of meat analogs products by source of protein, per 100 g (mean ± SD).

Table 2.

Nutritional value of different type of meat analogs products by containing animal-sourced ingredients, per 100 g (mean ± SD).

4. Discussion

The choice to consume or avoid specific types of meat analogs is driven largely by personal preference or health reasons. Consumers who avoid wheat-based products may do so because of medical conditions (e.g., celiac disease, non-celiac gluten sensitivity and wheat allergy) or because they are following a special type of diet (e.g., gluten- and grain-free). Soy and nut allergies could be reasons for avoiding soy- and nut-based meat analogs, respectively. Additionally, genetically modified soybean is a common ingredient in commercial products; people trying to follow a non-GMO (genetically modified organism) diet could prefer the avoidance of soy-based products. Independently of egg allergy, there is an increasing number of people seeking total plant-based products. Meat analogs are mainly consumed by people searching for sustainable and nutritious foods. Therefore, consumers may compare sustainability and nutrition differences when selecting specific meat analogs. Consumer information regarding these attributes validates the need for additional research.

In the current investigation we assessed the carbon footprint and nutrient composition of more than 50 meat analog products according to the main source of protein and the presence of eggs. An ever-increasing number of protein sources are being used to produced meat analogs. Vegetable proteins are currently the main source of material for meat analogs, especially gluten of wheat and soybean protein [29]. Others, such as protein derived from pulses, nuts or vegetables, are also utilized. The current analysis assesses specifically plant-based meat analogs. The majority of the meat analogs we analyzed (49 out of 56) were either wheat-based products and/or soy-based products.

Previously, the assessment of carbon footprint data for meat analogs focused on the description of the GHG emissions of the analogs [32,34]. Other reports compared the emissions of meat analogs with animal-based products [34,36]. Few studies showed differences between various types of meat analogs. We recently published a comparison of the emissions of meat analogs, but differences were reported according to their commercial preparation (i.e., burger, sausage) or format (i.e., canned, frozen) [35]. In another study, Smetana et al. reported the GHG emissions of meat analogs by the main source of protein [33], with results similar to those of our study. For the 32 wheat-based products we assessed in the current study, the GHG emissions ranged from 0.12 to 0.39 kg CO2e/100 g product compared to 0.36–0.40 kg CO2e/100 g reported by Smetana et al. [33]. For the seven soy-based products we assessed, GHG emissions ranged from 0.13 to 0.36 kg CO2e/100 g, a level comparable to that reported elsewhere for soy-based products (0.27–0.28 kg CO2e/100 g) [33]. We note that in the study by Smetana et al., no statistical comparisons were performed and the research group only assessed one product of each type, while in our study 56 different products were analyzed. Our results showed no major differences in GHG emissions according to plant protein source. This lack of variation is in accordance with previous publications reporting little variation in the GHG emission among different plant-based products [22]. However, the presence of eggs in the analogs significantly increased the GHG emissions. Our results are consistent with other authors who reported that when animal ingredients are used in the production of the analogs, the GHG emissions increase [33]. This is primarily because more GHGs are released during the production of animal-derived foods than the production of plant foods [22].

Although some variation was seen among the various products (see Table 1 and Table 2), the nutritional analyses of the meat analogs showed no large differences in the nutrient profiles. The meat analogs contained a good supply of protein, about 20–25 g per 100 g, which represents 35–55% of the adult Daily Reference Value. They are all low in saturated fat (less than 2 g/100 g) and have no cholesterol. Sodium levels in 100 g portions of meat analogs averaged only about 7% to 12% of the upper limit of daily sodium intake. The meat analogs contained an average only 6–12 g fat/100 g portion. Because of the nutritional composition of soy [46], the soy-based products are richer in omega-3 fatty acids and the important minerals iron and zinc. They also have greater levels of many of the B vitamins, as well as containing the health-promoting isoflavonoids. In addition, the amino acid profile of soy is a complete protein source, containing all nine essential amino acids necessary for human nutrition. As expected, the nut-based meat analogs were rich in the healthy monounsaturated fatty acids [37], and regular nut consumption has been associated with health benefits in numerous studies [47]. Nevertheless, the most favorable nutrient profile of soy- and nut-based products could not be relevant enough to differentially affect individual health, especially if consumption of meat analogs is integrated into a well-balanced diet.

Egg is used in the production of meat analogs for sensory attributes, rather than providing the main source of protein [29]. It is worth highlighting the fact that while the presence of a small amount of animal-sourced ingredients (i.e., eggs) does not change the nutritional profile of our products, their presence results in a significantly higher carbon footprint.

Our results may have an immediate application. No major differences in carbon footprint and nutritional composition of meat analogs exist among products with differences in their main source of protein. This fact provides support to consumers who opt for a certain type of product, but who are at the same time aware of the sustainability and nutritional composition of their foods. In addition, the knowledge that total plant-based products are significantly less damaging to the environment than products with egg could be a factor to influence the consumer to choose an egg-free meat analog product.

The current study has some limitations. Our life cycle assessment only covers from farm to factory gate. Retailing, cooking and waste disposal go beyond the scope of the present report. Nevertheless, their inclusion would not seem to vary the main comparative results. On the other hand, a major novelty of the current study is that we are the first to report on primary data of the GHG emissions and nutritional values for a large number of commercially available plant protein-rich meat analogs, differentiating them by ingredient composition.

5. Conclusions

The GHG emissions and the nutritional composition of the meat analogs was quite similar among products having different plant protein sources. However, products with animal-sourced ingredients had a higher environmental impact than those totally plant-based, without differences in their nutritional profile to totally plant-based meat analogs. Therefore, total plant-based meat analogs should be the choice for the sake of the environment. The research advances the current knowledge in the field of meat analogs, being the first in comparing the carbon footprint and the nutritional profile of meat analogs with differences in their main source of plant protein. Nevertheless, there are currently in the marketplace analogs based upon other sources of proteins, such as mycoproteins or insects, which are out of the scope of this research. Future studies focused at differences in sustainability and nutritional composition of meat analogs should also include these products.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/11/12/3231/s1, Table S1: Greenhouse gas emissions (kg CO2e) of different meat analogs by source of protein and presence of animal-sourced ingredients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, U.F. and J.S.; Data curation, U.F., M.A.M. and K.J.-S.; Formal analysis, U.F.; Funding acquisition, J.S.; Investigation, M.A.M.; Methodology, U.F.; Software, M.A.M. and K.J.-S.; Writing–original draft, U.F. and W.J.C.; Writing–review & editing, U.F., W.J.C. and J.S.

Funding

This research was funded by the McLean Fund for Nutrition Research.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all 3 meat analog factories for allowing us to access their site, interview personnel, and collect detailed production data. We also would like to thank Jan Irene Lloren and Hemangi Bipin Mavadiya for their technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Boeing, H.; Bechthold, A.; Bub, A.; Ellinger, S.; Haller, D.; Kroke, A.; Leschik-Bonnet, E.; Müller, M.J.; Oberritter, H.; Schulze, M.B.; et al. Critical review: Vegetables and fruit in the prevention of chronic diseases. Eur. J. Nutr. 2012, 51, 637–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rippe, J.M.; Angelopoulos, T.J. Relationship between Added Sugars Consumption and Chronic Disease Risk Factors: Current Understanding. Nutrients 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warensjo, E.; Nolan, D.; Tapsell, L. Dairy food consumption and obesity-related chronic disease. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2010, 59, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burlingame, B.; Dernini, S. Sustainable diets and biodiversity: Directions and solutions for policy, research and action. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Symposium Biodiversity and Sustainable Diets United Against Hunger, FAO, Rome, Italy, 3–5 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, J.L.; Fanzo, J.C.; Cogill, B. Understanding Sustainable Diets: A Descriptive Analysis of the Determinants and Processes That Influence Diets and Their Impact on Health, Food Security, and Environmental Sustainability. Adv. Nutr. 2014, 5, 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinfeld, H.; Gerber, P.; Wassenaar, T.; Castel, V.; Rosales, M.; de Haan, C. Livestock’s Long Shadow; Environmental Issues and Options; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2006; pp. 1–407. [Google Scholar]

- Tukker, A.; Guinee, J.; Heijungs, R.; de Koning, A.; van Oers, L.; Suh, S.; Geerken, T.; Van Holderbeke, M.; Jansen, B.; Nielsen, P. Environmental Impact of PRoducts (EIPRO) Analysis of the Life Cycle Environmental Impacts Related to the Final Consumption of the EU-25; Institue for Prospective Technological Studies: Seville, Spain, 2006; pp. 1–141. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, J.A.; Ramankutty, N.; Brauman, K.A.; Cassidy, E.S.; Gerber, J.S.; Johnston, M.; Mueller, N.D.; O’Connell, C.; Ray, D.K.; West, P.C.; et al. Solutions for a cultivated planet. Nature 2011, 478, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popp, A.; Lotze-Campen, H.; Bodirsky, B. Food consumption, diet shifts and associated non-CO2 greenhouse gases from agricultural production. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2010, 20, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabate, J.; Soret, S. Sustainability of plant-based diets: Back to the future. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 476S–482S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garnett, T. Where are the best opportunities for reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the food system (including the food chain)? Food Policy 2011, 36, S23–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springmann, M.; Clark, M.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Wiebe, K.; Bodirsky, B.L.; Lassaletta, L.; de Vries, W.; Vermeulen, S.J.; Herrero, M.; Carlson, K.M.; et al. Options for keeping the food system within environmental limits. Nature 2018, 562, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Springmann, M.; Wiebe, K.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Sulser, T.B.; Rayner, M.; Scarborough, P. Health and nutritional aspects of sustainable diet strategies and their association with environmental impacts: A global modelling analysis with country-level detail. Lancet Planet. Health 2018, 2, e451–e461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Dietetic Association; Dietitians Association of Canada. Position of the American Dietetic Association and dietitians of Canada: Vegetarian diets. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2003, 64, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melina, V.; Craig, W.; Levin, S. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Vegetarian Diets. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 1970–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, W.J.; Mangels, A.R.; American Dietetic Association. Position of the American Dietetic Association: Vegetarian diets. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, 1266–1282. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Archundia Herrera, M.C.; Subhan, F.B.; Chan, C.B. Dietary Patterns and Cardiovascular Disease Risk in People with Type 2 Diabetes. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2017, 6, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinu, M.; Abbate, R.; Gensini, G.F.; Casini, A.; Sofi, F. Vegetarian, vegan diets and multiple health outcomes: A systematic review with meta-analysis of observational studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 3640–3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, L.; Sabaté, J. Beyond Meatless, the Health Effects of Vegan Diets: Findings from the Adventist Cohorts. Nutrients 2014, 6, 2131–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soret, S.; Mejia, A.; Batech, M.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Harwatt, H.; Sabate, J. Climate change mitigation and health effects of varied dietary patterns in real-life settings throughout North America. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 490S–495S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fresan, U.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Sabate, J.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. Global sustainability (health, environment and monetary costs) of three dietary patterns: Results from a Spanish cohort (the SUN project). BMJ Open 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clune, S.; Crossin, E.; Verghese, K. Systematic review of greenhouse gas emissions for different fresh food categories. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 766–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresan, U.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Sabate, J.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. The Mediterranean diet, an environmentally friendly option: Evidence from the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra (SUN) cohort. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 1573–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruby, M.B. Vegetarianism. A blossoming field of study. Appetite 2012, 58, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenfeld, D.L. The psychology of vegetarianism: Recent advances and future directions. Appetite 2018, 131, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrin, T.; Papadopoulos, A. Understanding the attitudes and perceptions of vegetarian and plant-based diets to shape future health promotion programs. Appetite 2017, 109, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodland, R.; Anhang, J. Livestock and Climate Change: What If the Key Actors in Climate Change are Cows, Pigs, and Chickens; World Watch Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; Available online: http://www.worldwatch.org/files/pdf/Livestock%20and%20Climate%20Change.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2018).

- Malav, O.P.; Talukder, S.; Gokulakrishnan, P.; Chand, S. Meat analog: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 55, 1241–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Chatli, M.K.; Mehta, N.; Singh, P.; Malav, O.P.; Verma, A.K. Meat analogues: Health promising sustainable meat substitutes. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mintel. Meat Alternatives—US—June 2013. 2015. London, UK. Available online: https://store.mintel.com/meat-alternatives-us-june-2013 (accessed on 25 March 2018).

- Hoek, A.C.; Luning, P.A.; Weijzen, P.; Engels, W.; Kok, F.J.; de Graaf, C. Replacement of meat by meat substitutes. A survey on person- and product-related factors in consumer acceptance. Appetite 2011, 56, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, B.; Moses, R.; Sammons, N.; Birkved, M. Potential to curb the environmental burdens of American beef consumption using a novel plant-based beef substitute. PLoS ONE 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smetana, S.; Mathys, A.; Knoch, A.; Heinz, V. Meat Alternatives: Life Cycle Assessment of Most Known Meat Substitutes. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2015, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, M.C.; Keoleian, G.A. Beyond Meat’s Beyond Burger Life Cycle Assessment: A Detailed Comparison between A Plant-Based and An Animal-Based Protein Source; Center for Sustainable Systems, University of Michigan: 2018. Available online: http://css.umich.edu/sites/default/files/publication/CSS18-10.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2019).

- Mejia, M.A.; Fresán, U.; Harwatt, H.; Oda, K.; Uriegas-Mejia, G.; Sabaté, J. Life Cycle Assessment of the Production of a Large Variety of Meat Analogs by Three Diverse Factories. J. Hunger. Environ. Nutr. 2019, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettling, J.; Qingshi, T.; Faist, M.; DelDuce, A.; Mandlebaum, S. A Comparitive Life Cycle Assessment of Plant-Based Foods and Meat Foods; Quantis: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Nutrient Data Laboratory. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Legacy. Version Current: April 2018. Available online: https://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/ (accessed on 14 May 2018).

- The National Chicken Council. Per Capita Consumption of Poultry and Livestock, 1965 to Estimated 2019, in Pounds. 2019. Available online: https://www.nationalchickencouncil.org/about-the-industry/statistics/per-capita-consumption-of-poultry-and-livestock-1965-to-estimated-2012-in-pounds/ (accessed on 4 June 2019).

- International Agency for Research on Cancer Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risk to Humans. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. In Red Meat and Processed Meat; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Heller, M.C.; Keoleian, G.A. Life cycle energy and greenhouse gas analysis of a large-scale vertically integrated organic dairy in the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 1903–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandars, D.L.; Audsley, E.; Cañete, C.; Cumby, T.R.; Scotford, I.M.; Williams, A.G. Environmental Benefits of Livestock Manure Management Practices and Technology by Life Cycle Assessment. Biosyst. Eng. 2003, 84, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkat, K. Comparison of twelve organic and conventional farming systems: A life cycle greenhouse gas emissions perspective. J. Sustain. Agric. 2012, 36, 620–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SimaPro [computer software]. Pre Product Ecology Consultants, 8th ed.; Amersfoort, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jolliet, O.; Margni, M.; Charles, R.; Humbert, S.; Payet, J.; Rebitzer, G.; Rosenbaum, R. IMPACT 2002+: A New Life Cycle Impact Assessment Methodology. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schakel, S.F.; Sievert, Y.A.; Buzzard, I.M. Sources of data for developing and maintaining a nutrient database. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1988, 88, 1268–1271. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.; Kumar, R.; Sabapathy, S.N.; Bawa, A.S. Functional and Edible Uses of Soy Protein Products. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2008, 7, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, R.G.M.; Schincaglia, R.M.; Pimentel, G.D.; Mota, J.F. Nuts and Human Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).