Verification of the Role of the Experiential Value of Luxury Cruises in Terms of Price Premium

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Experiential Value

2.2. Well-Being Perception

2.3. Price Premium

2.4. Relationships among Study Variables

2.5. Gender Difference

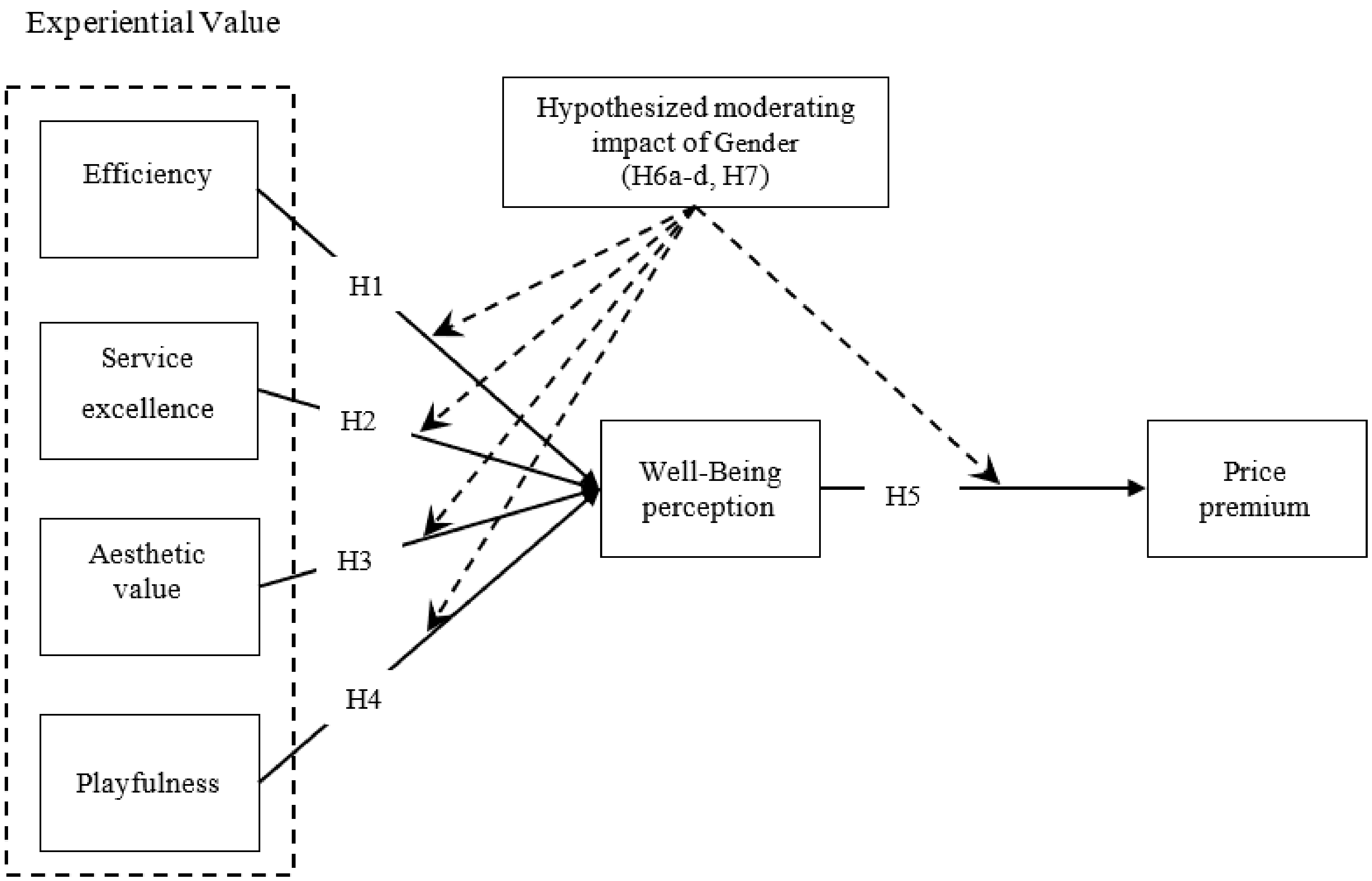

2.6. Proposed Model

3. Methods

3.1. Measurement and Questionnaire Development

3.2. Data Collection and Sample Profile

4. Results

4.1. Data Quality Testing

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion and Implications

6. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Efficiency |

| - This cruise trip is an efficient way to take my vacation. - This cruise trip makes my leisure life easier. - This cruise trip fits with my vacation schedule. |

| Service Excellence |

| - When I think of this cruise trip, I think of service excellence. - I think of this cruise brand as an expert in the cruise industry. - The cruise brand has my best interests at heart. |

| Aesthetic Value |

| - The ship was an attractive setting for my vacation. - The environment of the ship showed close attention to design details. - It was pleasant just being in the attractive cruise facilities. - I felt a real sense of harmony on the cruise ship. |

| Playfulness |

| - A cruise trip with this brand makes me feel cheerful. - I feel happy when I take a cruise trip with this brand. - A cruise trip with this brand makes me forget my troubles. |

| Well-Being Perception |

| - This cruise trip satisfies my overall travel needs. - This cruise trip plays a very important role in my social well-being. - This cruise trip plays an important role in my travel well-being. |

| Price Premium |

| - I am willing to pay a higher price for this cruise brand than for other cruise brands. - Even if other cruise brands are priced lower, I will still buy this cruise brand. - Even though this cruise brand seems comparable to other brands, I am willing to pay more to travel with this cruise brand. |

References

- Hwang, J.; Han, H. Examining strategies for maximizing and utilizing brand prestige in the luxury cruise industry. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 244–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruise Market Watch. Cruise Market Watch Announces 2011 Cruise Line Market Share and Revenue Projections. Available online: http://www.cruisemarketwatch.com/articles/cruise-marketwatch-announces-2011-cruise-line-market-share-and-revenueprojections (accessed on 11 December 2011).

- Ioana-Daniela, S.; Hyun, S.S.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, I.; Kang, S. Attitude toward luxury cruise, fantasy, and willingness to pay a price premium. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 23, 325–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S.H. Predictor of luxury cruise travelers’ well-being perception and perceived price fairness–A moderating role of other customer perception. Korea Acad. Soc. Tour. Manag. 2014, 29, 123–143. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigneron, F.; Johnson, L.W. A review and a conceptual framework of prestige-seeking consumer behavior. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 1999, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Belen del Rio, A.; Vazquez, R.; Iglesias, V. The effects of brand associations on consumer response. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 410–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.W.; Maclnnis, D.J.; Priester, J.; Eisingerich, A.B.; Iacobucci, D. Brand attachment and brand attitude strength: Conceptual and empirical differentiation of two critical brand equity drivers. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S.S.; Han, H. Luxury Cruise Travelers: Other Customer Perception. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobsin, J.S.P. Analysis of the US cruise line industry. Tour. Manag. 1993, 14, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Vina, L.; Ford, J. Logistic regression analysis of cruise vacation market potential: Demographic and trip attribute perception factors. J. Travel Res. 2001, 39, 406–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgsdottir, I.; Oskarsson, G. Segmentation and targeting in the cruise industry: An insight from practitioners serving passengers at the point of destination. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2017, 8, 350–364. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, T.H.; Huang, Y.Y. The impact of experiential marketing on customers experiential value and satisfaction: An empirical study in Vietnam hotel sector. J. Bus. Manag. Soc. Sci. Res. 2015, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.H.; Liang, R.D. Effect of experiential value on customer satisfaction with service encounters in luxury-hotel restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.B.; Yeh, S.S.; Huan, T.C. Nostalgic emotion, experiential value, brand image, and consumption intentions of customers of nostalgic-themed restaurants. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Dipietro, R.B.; So, K.K.F. Increasing experiential value and relationship quality: An investigation of pop-up dining experiences. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 74, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathwick, C.; Malhotra, N.; Rigdon, E. Experiential value: Conceptualization, measurement and application in the catalog and internet shopping environment. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.C.; Cheng, C.C.; Ai, C.H. A study of experiential quality, experiential value, trust, corporate reputation, experiential satisfaction and behavioral intentions for cruise tourists: The case of Hong Kong. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 200–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.H.; Wu, C.K. Relationships among experiential marketing, experiential value, and customer satisfaction. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2008, 32, 387–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B.J.; Darden, W.R. Consumer self-regulation in a retail environment. J. Retail. 1995, 71, 7–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B. The Nature of Customer Value: An Axiology of Services in the Consumption Experience. In Service Quality: New Directions in Theory and Practice; Roland, T.R., Richard, L.O., Eds.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, Y.J.; Hyun, S.S.; Kim, I. Vivid-memory formation through experiential value in the context of the international industrial exhibition. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 291–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, N.; Line, N.D.; Goh, B. Experiential value, relationship quality, and customer loyalty in full-service restaurants: The moderating role of gender. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2013, 22, 679–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzeskowiak, S.; Sirgy, M.J. Consumer well-being (CWB): The effects of self-image congruence, brand-community belongingness, brand loyalty, and consumption regency. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2007, 2, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, B.L.; Lee, S.; Kim, H.C.; Han, H. Investigating the key drivers of traveler loyalty in the airport lounge setting. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 651–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.J.; Sirgy, M.J.; Larsen, V.; Wright, N.D. Developing a subjective measure of consumer well-being. J. Macromark. 2002, 22, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Lee, D.J.; Rahtz, D. Research in consumer well-being (CWB): Overview of the field and introduction to the special issue. J. Macromark. 2007, 27, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Füller, J.; Matzler, K. Customer delight and market segmentation: An application of the three-factor theory of customer satisfaction on life style groups. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, D.; Abdullah, J. Holiday taking and the sense of well-being. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S. Green indoor and outdoor environment as nature-based solution and its role in increasing customer/employee mental health, well-being, and loyalty. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.J.; Sirgy, M.J. Quality-of-life (QOL) marketing: Proposed antecedents and consequences. J. Macromark. 2004, 24, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.C.; Chua, B.L.; Lee, S.; Boo, H.C.; Han, H. Understanding airline travelers’ perceptions of well-being: The role of cognition, emotion, and sensory experiences in airline lounges. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 1213–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Jeon, S.M.; Hyun, S.S. Chain restaurant patrons’ well-being perception and dining intentions: The moderating role of involvement. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 24, 402–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. If we are so rich, why aren’t we happy? Am. Psychol. 1999, 54, 821–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, S.; King, L.; Diener, E. The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychol. Bull. 2005, 131, 803–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netemeyer, R.G.; Krishnan, B.; Pullig, C.; Wang, G.; Yagci, M.; Dean, D.; Wirth, F. Developing and validating measures of facets of customer-based brand equity. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, E.; Jang, S.S. Price premiums for organic menus at restaurants: What is an acceptable level? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, S.; Pavlou, P.A. Evidence of the effect of trust building technology in electronic markets: Price premiums and buyer behavior. MIS Q. 2002, 26, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeoman, I.; McMahon-Beattie, U. Luxury markets and premium pricing. J. Revenue Pricing Manag. 2006, 4, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.W.; Mills, M.K. Contributing clarity by examining brand luxury in the fashion market. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1471–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, T.M.; Chen, S.H.; Chen, T.F. The relationships among experiential marketing, service innovation, and customer satisfaction-A case study of tourism factories in Taiwan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.H.; Quester, P.G. Modeling store loyalty: Perceived value in market orientation practice. J. Serv. Mark. 2006, 20, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Chung, H.; Rutherford, B. Social perspectives of e-contact center for loyalty building. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 64, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, N.; Douglas, N. Cruise Consumer Behavior: A Comparative Study. In Consumer Behavior in Travel and Tourism Industry; Pizam, A., Mansfeld, Y., Eds.; Haworth Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Dagger, T.S.; Sweeney, J.C. The effect of service evaluations on behavioral intentions and quality of life. J. Serv. Res. 2006, 9, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, M.; Maclnnis, D.J.; Park, C.W. The ties that bind: Measuring the strength of consumers’ emotional attachments to brands. J. Consum. Psychol. 2005, 15, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Lee, K.-S.; Chua, B.; Lee, S.; Kim, W. Role of airline food quality, price reasonableness, image, satisfaction, and attachment in building re-flying intention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, T.H.; Kim, J.; Yu, J.H. The differential roles of brand credibility and brand prestige in consumer brand choice. Psychol. Mark. 2010, 27, 662–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-Domecq, C.; Pritchard, A.; Segovia-Perez, M.; Morgan, N.; Villace-Molinero, T. Tourism gender research: A critical accounting. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 52, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Han, H.; Kim, S. How can employees engage customers? Application of social penetration theory to the full-service restaurant industry by gender. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 1117–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yu, J.; Kim, W. Investigating airline customers’ decision-making process for emerging environmentally-responsible airplanes: Influence of gender and age. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 31, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Lee, J.J.; Hwang, J. A study of brand prestige in the casino industry: The moderating role of customer involvement. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2018, 18, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, G.; Gill, T. Application of evolutionary psychology in marketing. Psychol. Mark. 2000, 17, 1005–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, M.; Ansic, D. Gender differences in risk behavior in financial decision-making: An experimental analysis. J. Econ. Psychol. 1997, 18, 605–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charness, G.; Gneezy, U. Strong Evidence for Gender Differences in Risk Taking. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2012, 83, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S.S. Creating a model of customer equity for chain restaurant brand formation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keng, C.J.; Huang, T.L.; Zheng, L.J.; Hsu, M.K. Modeling service encounters and customer experiential value in retailing: An empirical investigation of shopping mall customers in Taiwan. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2007, 18, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbing, D.W.; Anderson, J.C. An updated paradigm for scale development incorporating unidimensionality and its assessment. J. Mark. Res. 1988, 25, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Eom, T.; Chung, H.; Lee, S.; Ryu, H.B.; Kim, W. Passenger repurchase behaviours in the green cruise line context: Exploring the role of quality, image, and physical environment. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CR | Cronbach’s Alpha | EF | SE | AV | PF | WP | PP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EF | 0.862 | 0.809 | 0.822 | |||||

| SE | 0.867 | 0.827 | 0.647 a | 0.828 | ||||

| AV | 0.883 | 0.823 | 0.725 | 0.658 | 0.808 | |||

| PF | 0.868 | 0.808 | 0.711 | 0.717 | 0.700 | 0.828 | ||

| WP | 0.875 | 0.831 | 0.747 | 0.768 | 0.721 | 0.797 | 0.799 | |

| PP | 0.857 | 0.853 | 0.525 | 0.657 | 0.552 | 0.590 | 0.611 | 0.816 |

| Mean | 4.181 | 4.170 | 4.206 | 4.227 | 4.161 | 3.935 | ||

| SD | 0.709 | 0.741 | 0.662 | 0.689 | 0.673 | 0.878 |

| Hypothesis | Paths | Statement of Hypothesis | Coefficient (standardized) | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | EF → WP | EF will have a positive impact on WP | 0.221 ** | Supported |

| H2 | SE → WP | SE will have a positive impact on WP | 0.330 ** | Supported |

| H3 | AV→ WP | AV will have a positive impact on WP | 0.131 * | Supported |

| H4 | PP → WP | PP will have a positive impact on WP | 0.333 ** | Supported |

| H5 | WP → PP | WP will have a positive impact on PP | 0.611 ** | Supported |

| Paths | t-Value | Coefficient (standardized) | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Step 1) | |||

| EF → WP | 4.520 ** | 0.221 ** | Supported |

| SE → WP | 6.491 ** | 0.300 ** | Supported |

| AV → WP | 2.687 ** | 0.131 ** | Supported |

| PF → WP | 6.575 ** | 0.333 ** | Supported |

| (Step 2) | |||

| EF → PP | 0.506 | 0.036 | Not supported |

| SE → PP | 6.357 ** | 0.433 ** | Supported |

| AV → PP | 1.749 | 0.125 | Not supported |

| PF → PP | 2.227 * | 0.166 * | Supported |

| (Step 3) | |||

| EF→ PP | 0.134 | 0.010 | Not supported |

| SE→ PP | 5.428 ** | 0.397 ** | Supported |

| AV→ PP | 1.513 | 0.109 | Not supported |

| PF→ PP | 1.574 | 0.126 | Not supported |

| WP→ PP | 1.329 | 0.119 | Not supported |

| WP | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3.1 | Step 3.2 | Step 3.3 | Step 3.4 | |

| Independent Variable | ||||||

| EF | 0.221 ** | 0.222 ** | 0.272 ** | 0.221 ** | 0.228 ** | 0.224 ** |

| SE | 0.330 ** | 0.287 ** | 0.292 ** | 0.330 ** | 0.292 ** | 0.293 ** |

| AV | 0.131 ** | 0.134 * | 0.144 * | 0.135 * | 0.178 ** | 0.135 * |

| PP | 0.333 ** | 0.347 ** | 0.351 ** | 0.347 ** | 0.346 ** | 0.383 ** |

| Gender | −0.059 | 0.324 | 0.153 | 0.262 ** | 0.192 | |

| EF * Gender | −0.399 * | - | - | - | ||

| SE * Gender | −0.220 | - | - | |||

| AV * Gender | −0.333 | - | ||||

| PP * Gender | −0.262 | |||||

| R2 | 0.755 | 0.759 | 0.763 | 0.760 | 0.761 | 0.760 |

| ∆R2 | - | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| PP | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | |

| Independent Variable | |||

| WP | 0.611 ** | 0.614 * | 0.561 ** |

| Gender | −0.115 | −0.559 | |

| WP * Gender | 0.457 | ||

| R2 | 0.373 | 0.387 | 0.394 |

| ∆R2 | - | 0.013 | 0.008 |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, J. Verification of the Role of the Experiential Value of Luxury Cruises in Terms of Price Premium. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3219. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113219

Yu J. Verification of the Role of the Experiential Value of Luxury Cruises in Terms of Price Premium. Sustainability. 2019; 11(11):3219. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113219

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Jongsik. 2019. "Verification of the Role of the Experiential Value of Luxury Cruises in Terms of Price Premium" Sustainability 11, no. 11: 3219. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113219

APA StyleYu, J. (2019). Verification of the Role of the Experiential Value of Luxury Cruises in Terms of Price Premium. Sustainability, 11(11), 3219. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113219