Understanding the Antecedents of Organic Food Purchases: The Important Roles of Beliefs, Subjective Norms, and Identity Expressiveness

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. New Beliefs Regarding Organic Foods

2.2. Attitude, Purchase Attitude, and Purchase Intention

2.3. Identity Expressiveness

2.4. A New Path from Subjective Norms to Purchase Attitude

2.5. Perceived Trustworthiness

2.6. Household Income

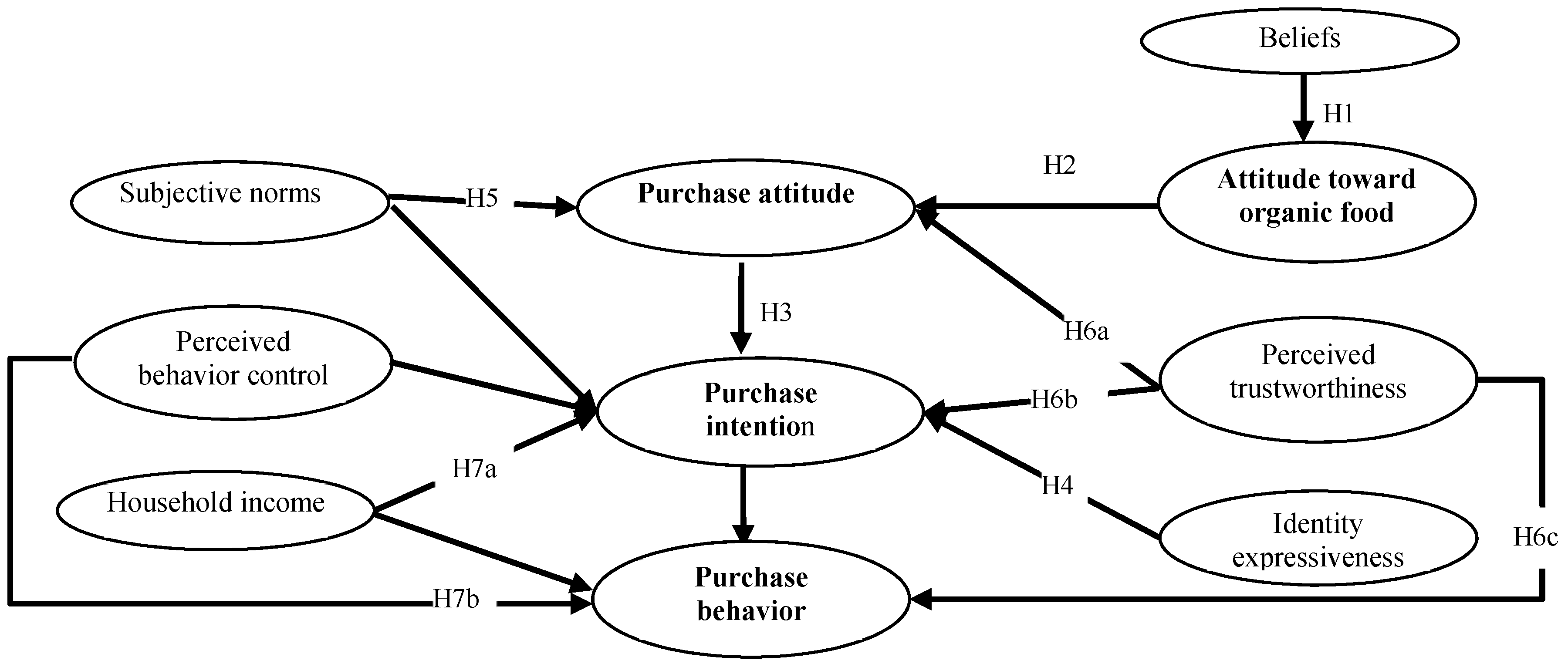

2.7. Conceptual Model

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Measurements of the Constructs

3.2. Data Collection and Sample

3.3. Data Analysis

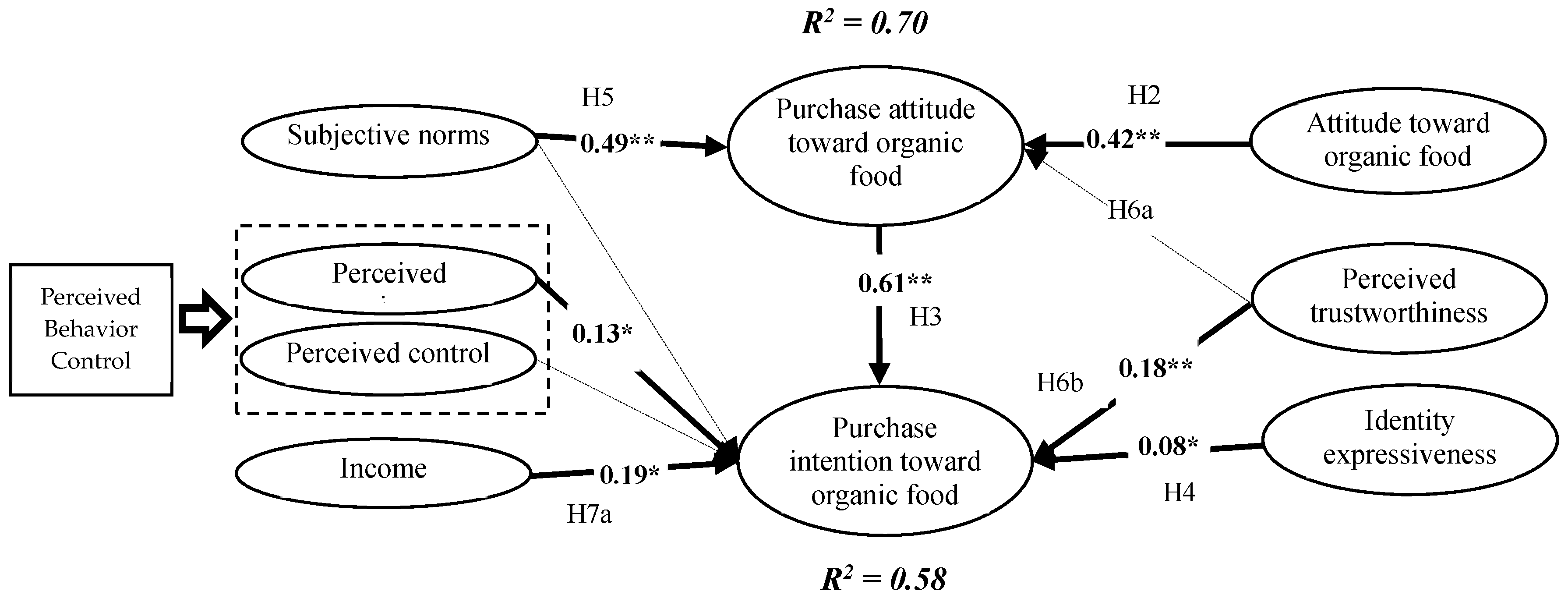

4. Results

4.1. From Belief to Attitude

4.2. From Attitude to Purchase Intention

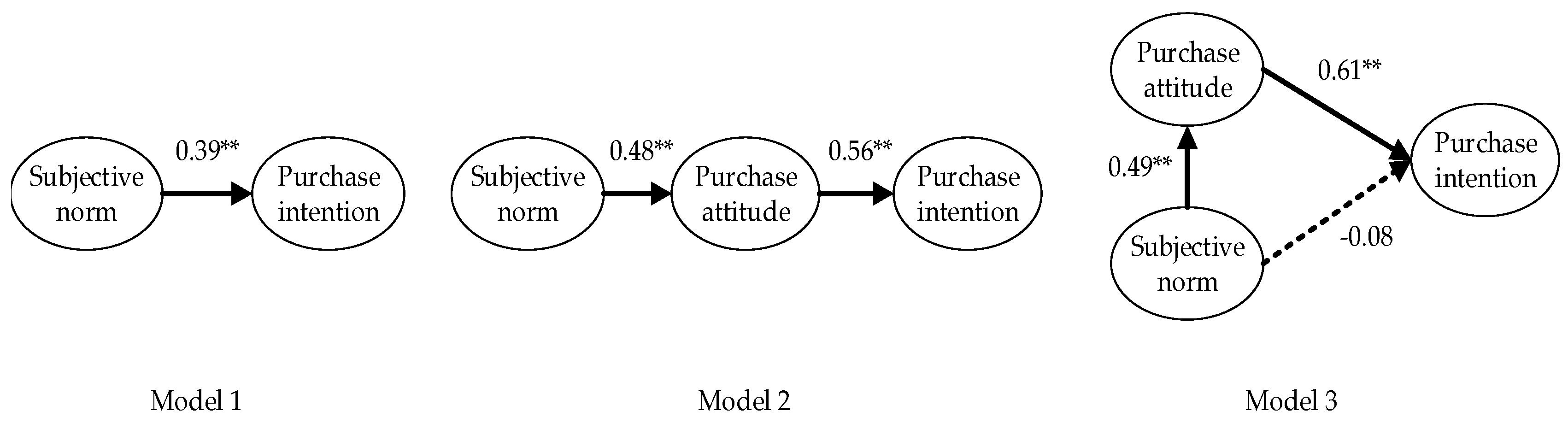

4.3. The Mediation Function of Purchase Attitude

4.4. From Purchase Intention to Purchase Behavior

5. Discussion

5.1. Outcomes of the Classical TPB Variables

5.2. Outcomes of the New Variables Identified by the Authors

5.3. Marketing Implications

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Constructs (Cronbach’s Value) | Items | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beliefs (Bi) [21,22,39,43] | Safer | 4.24 | 0.97 |

| More environmentally friendly | 4.14 | 1.03 | |

| More nutritious | 4.06 | 1.13 | |

| Luxuries for the rich | 3.80 | 1.25 | |

| Fewer categories | 3.68 | 1.07 | |

| Tastier | 3.51, | 1.19 | |

| More upscale | 3.47 | 1.17 | |

| Marketing hype | 2.96 | 1.16 | |

| Attitudes (Att) [40] | Do you agree that organic foods are better than non-organic foods in general? | 4.10 | 0.94 |

| Purchase attitudes (PAtt) [21] (0.78) | Attitude toward purchasing organic foods is extremely bad—extremely good | 3.94 | 0.74 |

| Extremely unpleasant—extremely pleasant | 3.54 | 1.08 | |

| I am strongly against–strongly for buying organic foods | 4.00 | 0.85 | |

| Identity expressiveness (IE) [31,44] (0.84) | I think the people around me think purchasing organic foods conforms to my taste and identity. | 3.02 | 0.98 |

| Purchasing organic foods makes me feel superior. | 2.84 | 1.09 | |

| Subjective norms (SN) [21,22,40] (0.77) | Those who influence your behaviors, such as family, close friends, and partners, think purchasing organic foods is extremely bad–extremely good. | 3.56 | 0.72 |

| Those who influence your behaviors, such as family, close friends, and sex partners, think you should purchase organic foods. | 3.76 | 0.86 | |

| Generally speaking, I do what these important others think I should do. | 3.77 | 1.05 | |

| Perceived easiness (PE) [21,40] | I could easily buy organic foods if I wanted to. | 2.50 | 0.92 |

| Perceived control (PC) [21,40] | I perceive I have a total control over the purchase of organic foods. | 3.89 | 1.03 |

| Perceived trustworthiness (PT) [41,42] (0.87) | How much do you trust: Organic farmers? (totally distrust—totally trust) | 3.45 | 0.86 |

| Organic processing enterprises? (totally distrust—totally trust) | 3.28 | 0.92 | |

| Government agencies that regulate organic foods? (totally distrust—totally trust) | 3.45 | 0.94 | |

| Organic certification authorities? (totally distrust —totally trust) | 3.51 | 0.87 | |

| Organic foods, in general? (totally distrust—totally trust) | 3.55 | 0.75 | |

| Household income (Inc) | Your household monthly income per capita is: no more than RMB 3000 (1); 3001–5000 (2); 5001–10,000 (3); more than 10,000 (4). | 1.60 | 0.76 |

| Purchase intention (PInt) [24,40] (0.72) | I intend to purchase organic foods during the next week. | 3.24 | 1.03 |

| I intend to purchase organic foods at the next food purchase. | 3.69 | 0.83 | |

| Purchase behavior (PBeh) [40] | During the one-month period prior to the survey, have you once purchased organic foods? “1”—Yes; “0”—No. | 0.26 | 0.44 |

References

- Rana, J.; Paul, J. Consumer Behavior and Purchase Intention for Organic Food: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 38, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lairon, D. Nutritional quality and safety of organic food. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 30, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Brzezina, N.; Kopainsky, B.; Mathijs, E. Can organic farming reduce vulnerabilities and enhance the resilience of the European food system? A critical assessment using system dynamics structural thinking tools. Sustainability 2016, 8, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandall, P.G.; Seideman, S.; Ricke, S.C.; O’Bryan, C.A.; Fanatico, A.F.; Rainey, R. Organic poultry: consumer perceptions, opportunities, and regulatory issues. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2009, 18, 795–802. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.; PieniaK, Z.; Verbeke, W. Consumers’ attitudes and behavior towards safe food in China: A review. Food Control 2013, 33, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Gong, S. Consumer knowledge, attitude and behavior toward food safety. In Food Safety in China: Science, Technology, Management and Regulation; Jen, J., Chen, J., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell Inc.: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Lobo, A.; Rajendran, N. Drivers of organic food purchase intentions in mainland China—Evaluating potential customers’ attitudes, demographics and segmentation. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyub, S.; Wang, X.H.; Astif, M.; Ayyub, R.M. Antecedents of Trust in Organic Foods: The Mediating Role of Food Related Personality Traits. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.H.; Pacho, F.; Liu, J.; Kajungiro, R. Factors Influencing Organic Food Purchase Intention in Developing Countries and the Moderating Role of Knowledge. Sustainability 2019, 11, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wai, O.K. Organic Asia 2015. In The World of Organic Agriculture. Statistics and Emerging Trends 2016; Helga, W., Lernoud, J., Eds.; Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL), Frick, and IFOAM—Organics International: Bonn, Germany, 2016; pp. 172–181. [Google Scholar]

- Lernoud, J.; Willer, H. Current statistics on organic agriculture worldwide: Area, producers, markets and selected crops. In The World of Organic Agriculture. Statistics and Emerging Trends 2016; Helga, W., Lernoud, J., Eds.; Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL), Frick, and IFOAM—Organics International: Bonn, Germany, 2016; pp. 34–116. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, B.; Liu, H.; Chen, T. Trends in organic and green food consumption in China: Opportunities and challenges for regional Australian exporters. J. Econ. Soc. Policy 2015, 17, 6–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sahota, A. The global market for organic food & drink. In The World of Organic Agriculture. Statistics and Emerging Trends 2016; Helga, W., Lernoud, J., Eds.; Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL), Frick, and IFOAM—Organics International: Bonn, Germany, 2016; pp. 133–138. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Yin, S.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, D. Effectiveness of China’s organic food certification policy: Consumer preferences for infant milk formula with different organic certification labels. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2014, 62, 545–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lei, L. Type of Consumer Health-Enhancing Behaviors and Its Formation Mechanism. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 23, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; He, J. Influence factors of decision on organic food purchase. Consum. Econ. 2016, 32, 73–78. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Scalco, A.; Noventa, S.; Sartori, R.; Ceschi, A. Predicting organic food consumption: A meta-analytic structural equation model based on the theory of planned behavior. Appetite 2017, 112, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M. Consumer attitudes and purchase intentions in relation to organic foods in Taiwan: Moderating effects of food-related personality traits. Food Qual. Prefer. 2007, 18, 1008–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J.; Zhou, Y. Chinese consumers’ adoption of a ‘green’ innovation–The case of organic food. J. Mark. Manag. 2012, 28, 313–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Thøgersen, J.; Ruan, Y.; Huang, G. The moderating role of human values in planned behavior: The case of Chinese consumers’ intention to buy organic food. J. Consum. Mark. 2013, 30, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.; Kang, J.H. Face or subjective norm? Chinese college students’ purchase behaviors toward foreign brand jeans. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2010, 28, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. Modifying an American Consumer Behavior Model for Consumers in Confucian Culture. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 1991, 3, 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Swidi, A.; Sheikh, M.R.H.; Haroon Hafeez, M.; Mohd, N.M.S. The role of subjective norms in theory of planned behavior in the context of organic food consumption. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1561–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Intention to purchase organic food among young consumers: Evidences from a developing nation. Appetite 2016, 96, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkiainen, A.; Sundqvist, S. Subjective norms, attitudes and intentions of Finnish consumers in buying organic food. Br. Food J. 2005, 107, 808–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Guido, G.; Prete, M.I.; Pino, G. The impact of ethical self-identity and safety concerns on attitudes and purchasing intentions of organic food products. Behind Ethical Consum. 2009, 22, 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Guido, G.; Tedeschi, P.; Prete, M.I.; Franceschini, L.; Buffa, C. The influence of moral norms and self-identity in the choice of organic food products. Behind Ethical Consum. 2009, 28, 15–42. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, S.; Wu, L.; Du, L.; Chen, M. Consumers’ purchase intention of organic food in China. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010, 90, 1361–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, W. Consumer psychology of organic food. Consumption Daily, 14 August 2014; A02. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, P. A tipping point for organic food? China Food News, 24 February 2014; 003. [Google Scholar]

- Irianto, H. Consumers’ attitude and intention towards organic food purchase: An extension of theory of planned behavior in gender perspective. Int. J. Manag. Econ. Soc. Sci. 2015, 4, 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior, organizational behavior and human decision processes. J. Leis. Res. 1991, 50, 176–211. [Google Scholar]

- Tarigan, M.M. Consumer attitude and intention to buy organic food brand as a result of brand extension: An experimental approach. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Management Science & Engineering 17th Annual Conference Proceedings, Melbourne, Australia, 24–26 November 2010; Volume 3, pp. 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Thøgersen, J.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, G. How stable is the value basis for organic food consumption in China? J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 134, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patch, C.S.; Tapsell, L.C.; Peter, G.W. Attitudes and intentions toward purchasing novel foods enriched with omega-3 fatty acids. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2005, 37, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Chen, J.L.; Yen, D.C. Theory of planning behavior (tpb) and customer satisfaction in the continued use of e-service: An integrated model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2007, 23, 2804–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, R.; Sniehotta, F.; Schuz, B. Predicting binge-drinking behaviour using an extended tpb: Examining the impact of anticipated regret and descriptive norms. Alcohol. Alcohol. 2006, 42, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibah, U.; Hassan, I.; Iqbal, M.S.; Naintara. Household behavior in practicing mental budgeting based on the theory of planned behavior. Financ. Innov. 2018, 4, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maichum, K.; Parichatnon, S.; Peng, K.C. Developing an extended theory of planned behavior model to investigate consumers’ consumption behavior toward organic food: A case study in Thailand. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2017, 6, 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Thorbjørnsen, H.; Pedersen, P.E.; Nysveen, H. “This is who I am”: Identity expressiveness and the theory of planned behavior. Psychol. Mark. 2007, 24, 763–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Austin, W.G., Worchel, S., Eds.; Brooks/Cole: Monterey, CA, USA, 1979; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Terry, D.J.; Hogg, M.A.; White, K.M. The theory of planned behaviour: Self-identity, social identity and group norms. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 38, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, H.J.; Chung, J.; Pysarchik, D.T. Antecedents to new food product purchasing behavior among innovator groups in India. Eur. J. Mark. 2004, 38, 608–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobb, A.E.; Mazzocchi, M.; Traill, W.B. Modeling risk perception and trust in food safety information within the theory of planned behavior. Food Qual. Preference 2007, 18, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.A. Creating ethical food consumers? Promoting organic foods in urban Southwest China. Soc. Anthropol. 2009, 17, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Mao, Y.; Gale, F. Chinese consumer demand for food safety attributes in milk products. Food Policy 2008, 33, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, S.; Shih, C.; Wei, S.; Chen, Y. Attitudinal inconsistency toward organic food in relation to purchasing intention and behavior: An illustration of Taiwan consumers. Br. Food J. 2012, 114, 997–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuttavuthisit, K.; Thøgersen, J. The importance of consumer trust for the emergence of a market for green products: The case of organic food. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhu, H.; Le, M.; Wu, Y. The effect of face consciousness on consumption of counterfeit luxury goods. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2014, 42, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Constructing a TPB Questionnaire: Conceptual and Methodological Considerations. 2006. Available online: http://www.people.umass.edu/aizen/pdf/tpb.measurement.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2013).

- Chen, M. Segmentation of Taiwanese consumers based on trust in the food supply system. Br. Food J. 2012, 114, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W. The effects of different types of trust on consumer perceptions of food safety. An empirical study of consumers in Beijing Municipality, China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2013, 5, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Su, C. How face influences consumption—A comparative study of American and Chinese consumers. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2007, 49, 237–256. [Google Scholar]

- Streiner, D.L.; Norman, G.R. Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Urban, J.; Zverinova, I.; Scasny, M. What motivates Czech consumers to buy organic food? Soc. Cas. 2012, 48, 509–536. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, L.; Tang, J.; Yang, Y.; Gong, S. Hygienic food handling intention. An application of the theory of planned behavior in the Chinese cultural context. Food Control 2014, 42, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Mackenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K.; Kim, S.S.; Patil, A. Common method variance in is research: A comparison of alternative approaches and a reanalysis of past research. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 1865–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, N.; Yin, C.; Zhang, J.X. Understanding the relationships between motivators and effort in crowdsourcing marketplaces: A nonlinear analysis. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 35, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Saraf, N.; Xue, H.Y. Assimilation of enterprise systems: The effect of institutional pressures and the mediating role of top management. MIS Q. 2007, 31, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.J. Recent advances in causal modeling methods for organizational and management research. J. Manag. 2003, 29, 903–936. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W.; Thatcher, J.B.; Wright, R.T. Assessing common method bias: Problems with the ULMC technique. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 1003–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doorn, S.V.; Heyden, M.; Tröster, C.; Volberda, H. Entrepreneurial orientation and performance: Investigating local requirements for entrepreneurial decision-making. Adv. Strategy Manag. 2015, 32, 211–241. [Google Scholar]

- Dutot, V.; Bergeron, F.; Raymond, L. Information management for the internationalization of SMES: An exploratory study based on a strategic alignment perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2014, 34, 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.; Brick, J.M.; Bates, N.A.; Battaglia, M.; Couper, M.P.; Dever, J.A.; Gile, K.J.; Tourangeau, R. Summary report of the AAPOR task force on non-probability sampling. J. Surv. Stat. Methodol. 2013, 1, 90–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavreck, L.; Rivers, D. The 2006 cooperative congressional election study. J. Elect. Public Opin. Parties 2008, 18, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiers, P. Using global organic markets to pay for ecologically based agricultural development in China. Agric. Hum. Values 2005, 22, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Wang, L.; Yang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M. Consumer perceptions and attitudes of organic food products in eastern china. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igbaria, M.; Zinatelli, N.; Cragg, P.B.; Cavaye, A. Personal computing acceptance factors in small firms: A structural equation model. MIS Q. 1997, 21, 279–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, F.M. Construct validity and error components of survey measures: A structural modeling approach. Public Opin. Q. 1984, 48, 409–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G.; Sörbom, D. LISREL 7: A Guide to the Program and Applications; SPSS: Chicago, IL, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, C.; Diamantopoulos, A. Using single-item measures for construct measurement in management research. Conceptual issues and application guidelines. Die Betr. 2009, 69, 195–210. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate data analysis. Technometrics 1998, 15, 648–650. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.; Choi, Y.; Youn, S.; Chun, J.U. Ethical leadership and employee moral voice: The mediating role of moral efficacy and the moderating role of leader–follower value congruence. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 141, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.K.; Chao, C.M. Internet misconduct impact adolescent mental health in Taiwan: The moderating roles of internet addiction. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2016, 14, 921–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li-Ying, J.; Wang, Y.; Ning, L. How do dynamic capabilities transform external technologies into firms’ renewed technological resources?—A mediation model. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2016, 33, 1009–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, R.; Dahdah, M.; Norman, P.; French, D.P. How well does the theory of planned behaviour predict alcohol consumption? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2016, 10, 148–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M. Attitude toward organic foods among Taiwanese as related to health consciousness, environmental attitudes, and the mediating effects of a healthy lifestyle. Br. Food J. 2009, 111, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loebnitz, N.; Aschemann-Witzel, J. Communicating organic food quality in china: Consumer perceptions of organic products and the effect of environmental value priming. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 50, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.E.; Gaus, H. Consumer response to negative media information about certified organic food products. J. Consum. Policy 2015, 38, 387–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyez, K.; Francis, J.N.P.; Smirnova, M.M. How individual, product and situational determinants affect the intention to buy organic food buying behavior: A cross-national comparison in five nations. Der Markt 2012, 51, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lobo, A. Organic food products in china: Determinants of consumers’ purchase intentions. Int. Rev. Ret. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2012, 22, 293–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgins, K.J.; Fraser, E.D.G. “we are a business, not a social service agency.” barriers to widening access for low-income shoppers in alternative food market spaces. Agric. Hum. Values 2017, 35, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Gao, Y.; Wu, L. Constructing the Food Safety Co-Governance System with Chinese Characteristics; The People Press: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, S.; Li, R.; Wu, L.; Chen, X. Introduction to 2018 China Development Report on Food Safety; Perking University Press: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Yan, Z.; Zhou, J. Consumer choices and motives for eco-labeled products in China: An empirical analysis based on the choice experiment. Sustainability 2017, 9, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Year | Beliefs | Theory of Planned Behavior | Other Factors | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC | EF | Taste | FS | Nutritious | PAtt | SN | PBC | Int | Att | Inc | PT | ||

| Tarkiainen and Sundqvist | 2005 | √(**) | √(**) | √(**) | √(**) | ||||||||

| Chen | 2007 | √(NS) | √(**) | √(NS) | √(**) | √(**) | √(**) | √(**) | |||||

| Chen | 2009 | √(**) | √(**) | ||||||||||

| Yin et al. | 2009 | √(NS) | √(NS) | √(NS) | √(**) | √(**) | |||||||

| Tarigan et al. | 2011 | √(**) | |||||||||||

| Urban et al. | 2012 | √(**) | √(**) | √(NS) | |||||||||

| Thøgersen and Zhou | 2012 | √(**) | √(**) | √(**) | √(**) | √(NS) | √(**) | √(**) | √(**) | ||||

| Tung et al. | 2012 | √(**) | |||||||||||

| Zhou et al. | 2013 | √(**) | √(NS) | √(**) | |||||||||

| Al-Swidi et al. | 2014 | √(**) | √(**) | √(NS) | |||||||||

| Chen et al. | 2014 | √(**) | √(**) | √(**) | |||||||||

| Irianto | 2015 | √(**) | √(**) | √(**) | √(**) | ||||||||

| Nuttavuthisit and Thøgersen | 2015 | √(**) | |||||||||||

| Xie et al. | 2015 | √(**) | √(**) | √(**) | √(**) | √(**) | |||||||

| Thøgersen et al. | 2016 | √(**) | |||||||||||

| Yadav and Pathak | 2016 | √(**) | √(**) | √(**) | √(NS) | √(**) | |||||||

| Wang and He | 2016 | √(**) | √(**) | √(**) | √(**) | √(**) | √(NS) | ||||||

| Maichum et al. | 2017 | √(**) | √(NS) | √(**) | √(**) | ||||||||

| Wang et al. | 2019 | √(**) | √(**) | √(**) | √(**) | ||||||||

| Demographic Characteristics | Category | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–35 | 68.3 |

| 36–55 | 31.7 | |

| Gender | Male | 46.1 |

| Female | 53.9 | |

| Educational level | Junior high school or below | 13 |

| Senior high school | 40.5 | |

| College and above | 46.5 | |

| Marital status | Unmarried | 41.2 |

| Married without children | 22.6 | |

| Married with children | 35.3 | |

| Others | 0.9 | |

| Per capita household monthly income | No more than 3000 | 54.9 |

| (Chinese Yuan) | 3001–5000 | 32.9 |

| 5001–10,000 | 10 | |

| >10,000 | 2.2 | |

| Place of residence | Urban | 76.7 |

| Rural | 23.3 | |

| Primary food purchaser or not | Yes | 35.9 |

| No | 64.1 | |

| Living with the elders of 60+ years of age or with kids below 12 years of age | Yes | 75.6 |

| No | 24.4 | |

| You buy organic foods: | For yourself to eat | 17.1 |

| For your family (such as the kids or elders) to eat | 71.5 | |

| As a gift for others | 11.4 |

| Beliefs | Standard β | t | Adjusted R2 | F | Tolerance | Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safer | 0.378 | 11.910 ** | 0.565 | 1.77 | ||

| More environmentally friendly | 0.167 | 5.478 ** | 0.61 | 1.64 | ||

| Luxuries for the rich | 0.148 | 5.646 ** | 0.822 | 1.216 | ||

| More nutritious | 0.125 | 4.687 ** | 0.798 | 1.254 | ||

| More upscale | 0.113 | 4.154 ** | 0.763 | 1.311 | ||

| Marketing hype | −0.108 | −4.043 ** | 0.43 | 127.365 ** | 0.793 | 1.262 |

| Variable | Att | PAtt | IE | SN | PE | PBC | PT | Inc | Pri | Pint | Mean | S.D. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Att a | 4.10 | 0.94 | ||||||||||

| PAtt | 0.584 * | 0.756 | 3.83 | 0.75 | ||||||||

| IE | 0.167 * | 0.242 * | 0.857 | 2.93 | 0.96 | |||||||

| SN | 0.505 * | 0.589 * | 0.262 * | 0.742 | 3.70 | 0.73 | ||||||

| PE a | −0.105 * | −0.208 * | −225 * | −0.166 * | 2.51 | 0.92 | ||||||

| PBC a | 0.361 * | 0.417 * | 0.072 ** | 0.504 * | −0.146 * | 3.89 | 1.03 | |||||

| PT | 0.419 * | 0.448 * | 0.296 * | 0.508 * | −0.055 | 0.375 * | 0.760 | 3.45 | 0.71 | |||

| Inc a | 0.138 * | 0.252 * | 0.243 * | 0.299 * | −101 * | 0.220 * | 0.259 * | —— | —— | |||

| Pri | 0.302 * | 0.261 * | −0.027 | 0.322 * | −0.096 * | 0.354 * | 0.122 * | 0.087 * | 4.46 | 0.85 | ||

| Pint | 0.436 * | 0.562 * | 0.225 * | 0.436 * | −0.044 | 0.311 * | 0.430 * | 0.293 * | 0.179 * | 0.762 | 3.46 | 0.83 |

| Fit | χ2 | df | χ2/df | CFI | GFI | NNFI | RMSEA | SRMA | AIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 1072.43 | 127 | 8.44 | 0.96 | 0.9 | 0.94 | 0.086 | 0.059 | 1198.43 |

| Model 2 | 881.94 | 126 | 7 | 0.97 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.077 | 0.045 | 1009.94 |

| Model 3 | 880.12 | 125 | 7.04 | 0.97 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.078 | 0.045 | 1010.12 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard β | S.E. | p | 95% C.I. for EXP (b) | Standard β | S.E. | p | 95% C.I. for EXP (b) | |||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||||

| PInt | 0.378 | 0.094 | 0.000 * | 1.212 | 1.756 | 0.363 | 0.095 | 0.000 ** | 1.193 | 1.733 |

| PE | 0.366 | 0.077 | 0.000 ** | 1.239 | 1.678 | 0.371 | 0.079 | 0.000 ** | 1.241 | 1.691 |

| PC | −0.37 | 0.088 | 0.000 ** | 0.581 | 0.82 | −0.366 | 0.089 | 0.000 ** | 0.583 | 0.825 |

| Inc | 0.546 | 0.079 | 0.000 ** | 1.481 | 2.015 | 0.502 | 0.084 | 0.000 ** | 1.402 | 1.946 |

| PT | 0.056 | 0.093 | 0.546 | 0.881 | 1.269 | 0.048 | 0.093 | 0.602 | 0.875 | 1.259 |

| (Constant) | −1.203 | 0.081 | 0.000 ** | |||||||

| Pint *Inc | 0.206 | 0.096 | 0.032 * | 1.018 | 1.484 | |||||

| PE *Inc | 0.031 | 0.082 | 0.704 | 0.878 | 1.212 | |||||

| PC *Inc | −0.148 | 0.092 | 0.107 | 0.72 | 1.032 | |||||

| PT *Inc | 0.025 | 0.091 | 0.785 | 0.857 | 1.226 | |||||

| (Constant) | −1.217 | 0.085 | 0 | |||||||

| HL test | χ2 = 10.70, df = 8, p = 0.219 | χ2 = 12.97, df = 8, p = 0.113 | ||||||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.154 | 0.163 | ||||||||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bai, L.; Wang, M.; Gong, S. Understanding the Antecedents of Organic Food Purchases: The Important Roles of Beliefs, Subjective Norms, and Identity Expressiveness. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3045. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113045

Bai L, Wang M, Gong S. Understanding the Antecedents of Organic Food Purchases: The Important Roles of Beliefs, Subjective Norms, and Identity Expressiveness. Sustainability. 2019; 11(11):3045. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113045

Chicago/Turabian StyleBai, Li, Mingliang Wang, and Shunlong Gong. 2019. "Understanding the Antecedents of Organic Food Purchases: The Important Roles of Beliefs, Subjective Norms, and Identity Expressiveness" Sustainability 11, no. 11: 3045. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113045