Management Implications for the Most Attractive Scenic Sites along the Andalusia Coast (SW Spain)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

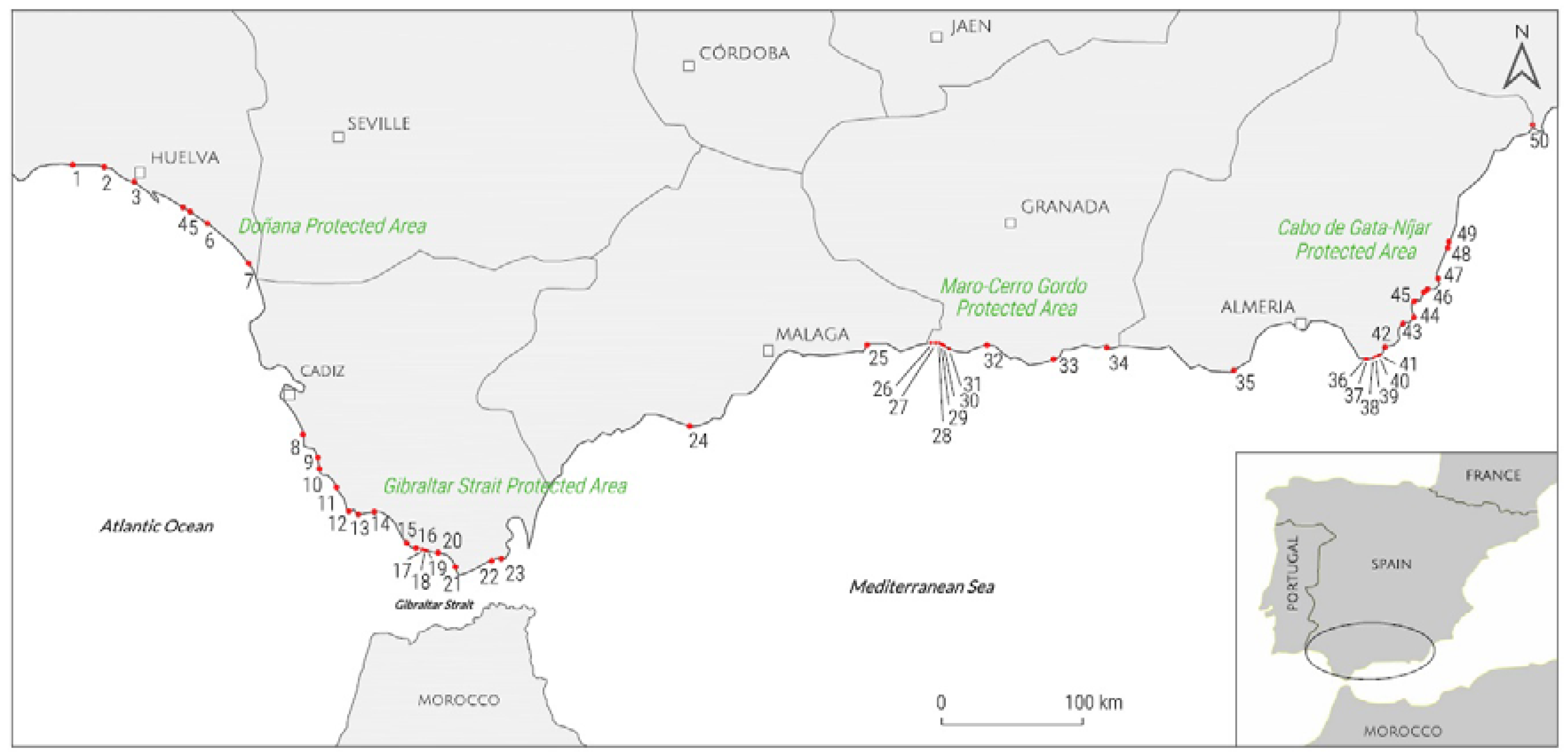

2. Study Area

3. Methodology

3.1. Preamble

3.2. Methodology Used

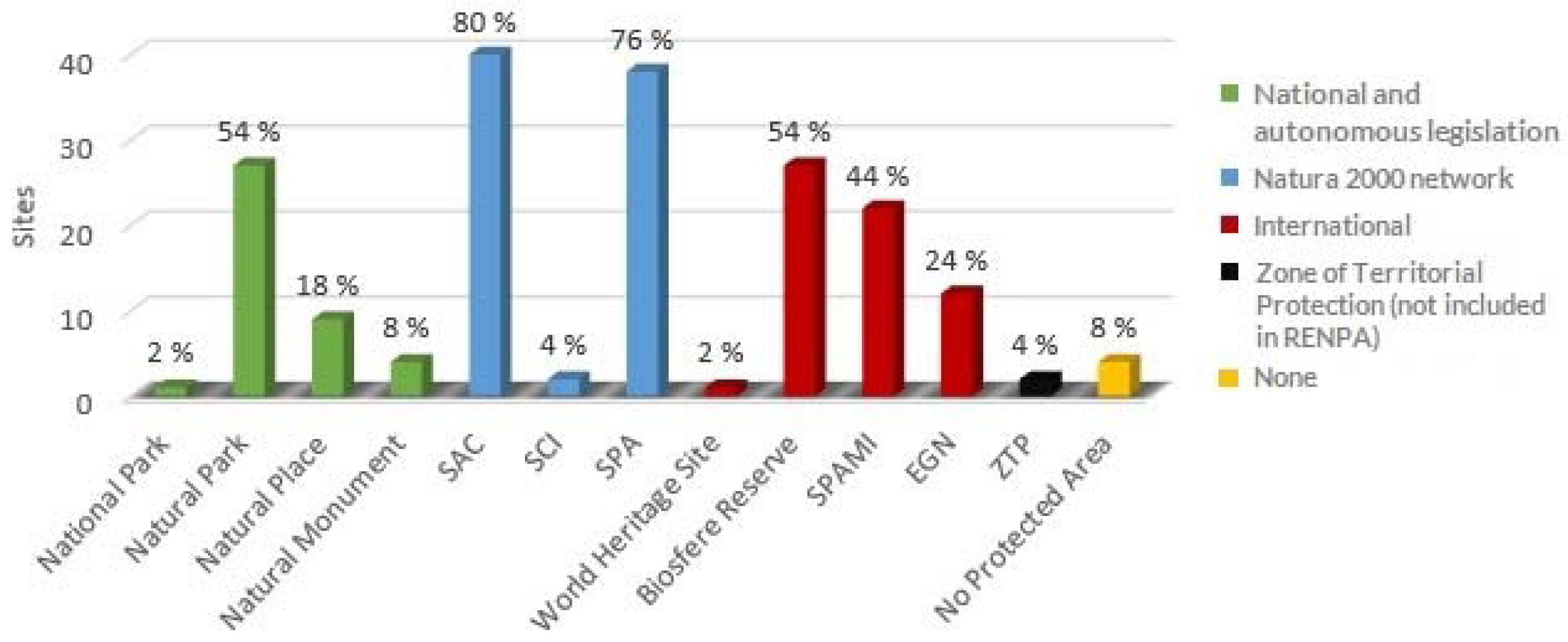

4. Protected Areas

5. Management Models

- (a)

- to identify the finest stretches of undeveloped coast;

- (b)

- to conserve scenic quality and foster leisure activities related to natural scenery and not on man made activities;

- (c)

- to support the sustainable use of the coast for public recreation; and,

- (d)

- to foster users awareness and understanding of conservation by maintaining and improving community involvement.

- -

- Intensive. These are the “honeypot” areas, where facilities provided are sufficient and designed to give the minimum effect on the beauty of the protected area but facilitate maximum public enjoyment; and,

- -

- Remote. The aim is to retain areas in a relatively inaccessible and untouched state. This protects fragile habitats from vehicles and people and provides enjoyment to people (i.e., walkers) who like solitude and an absence of vehicles.

- (a)

- determination of intensity of use;

- (b)

- management zones based on different intensities;

- (c)

- control of development;

- (d)

- regulation of access;

- (e)

- landscape improvements;

- (f)

- diversification of activities; and,

- (g)

- provision of interpretative services.

6. Results

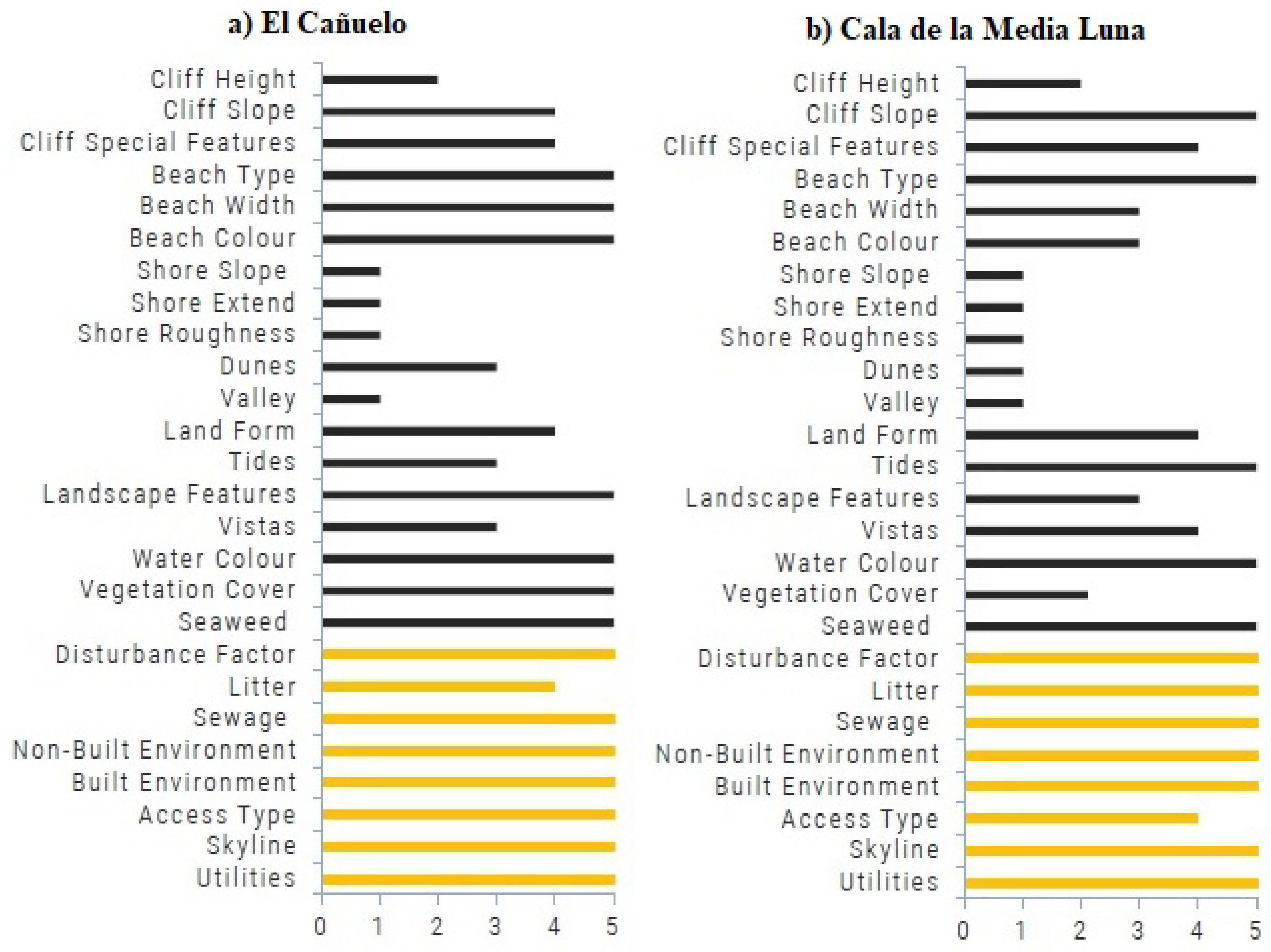

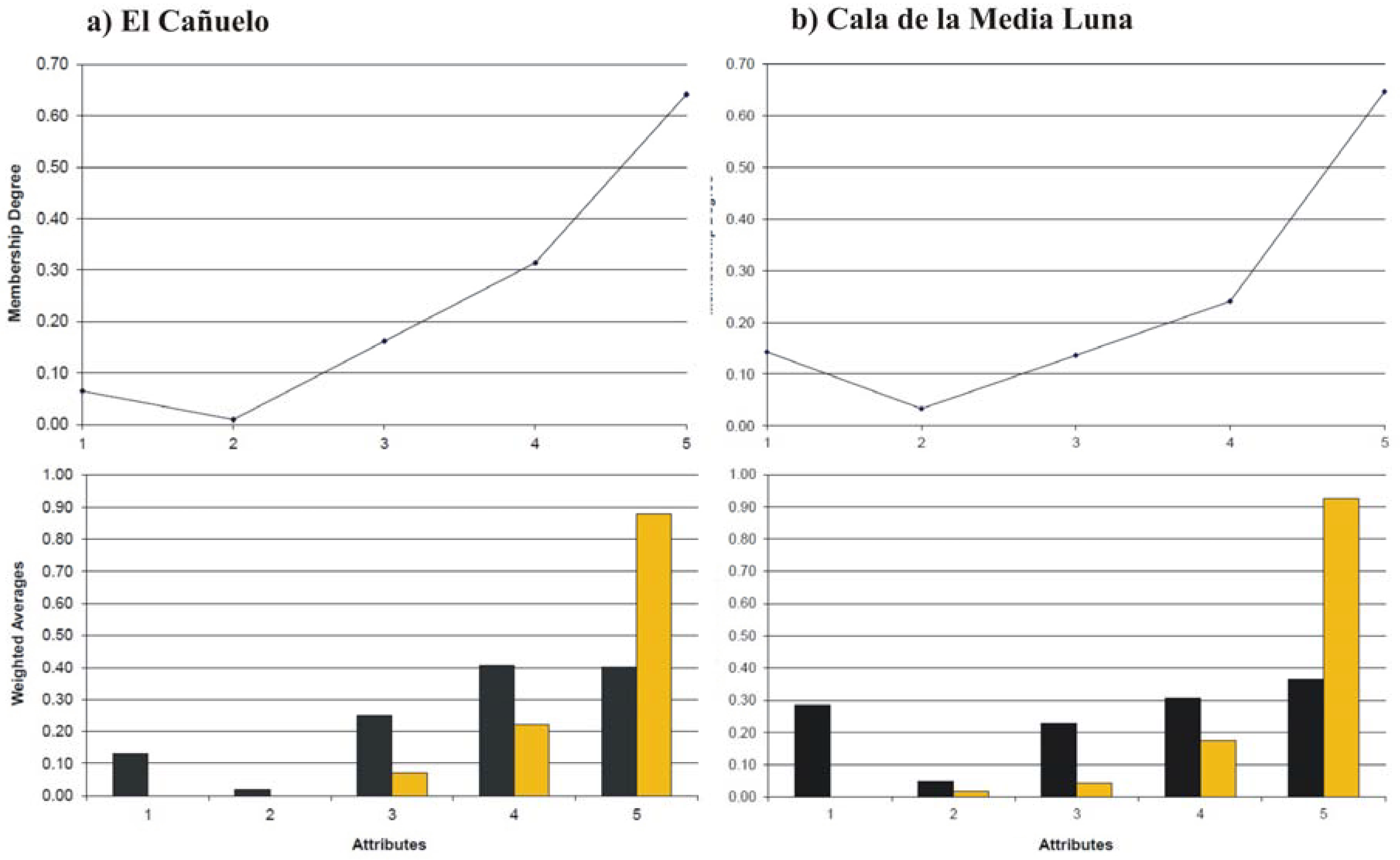

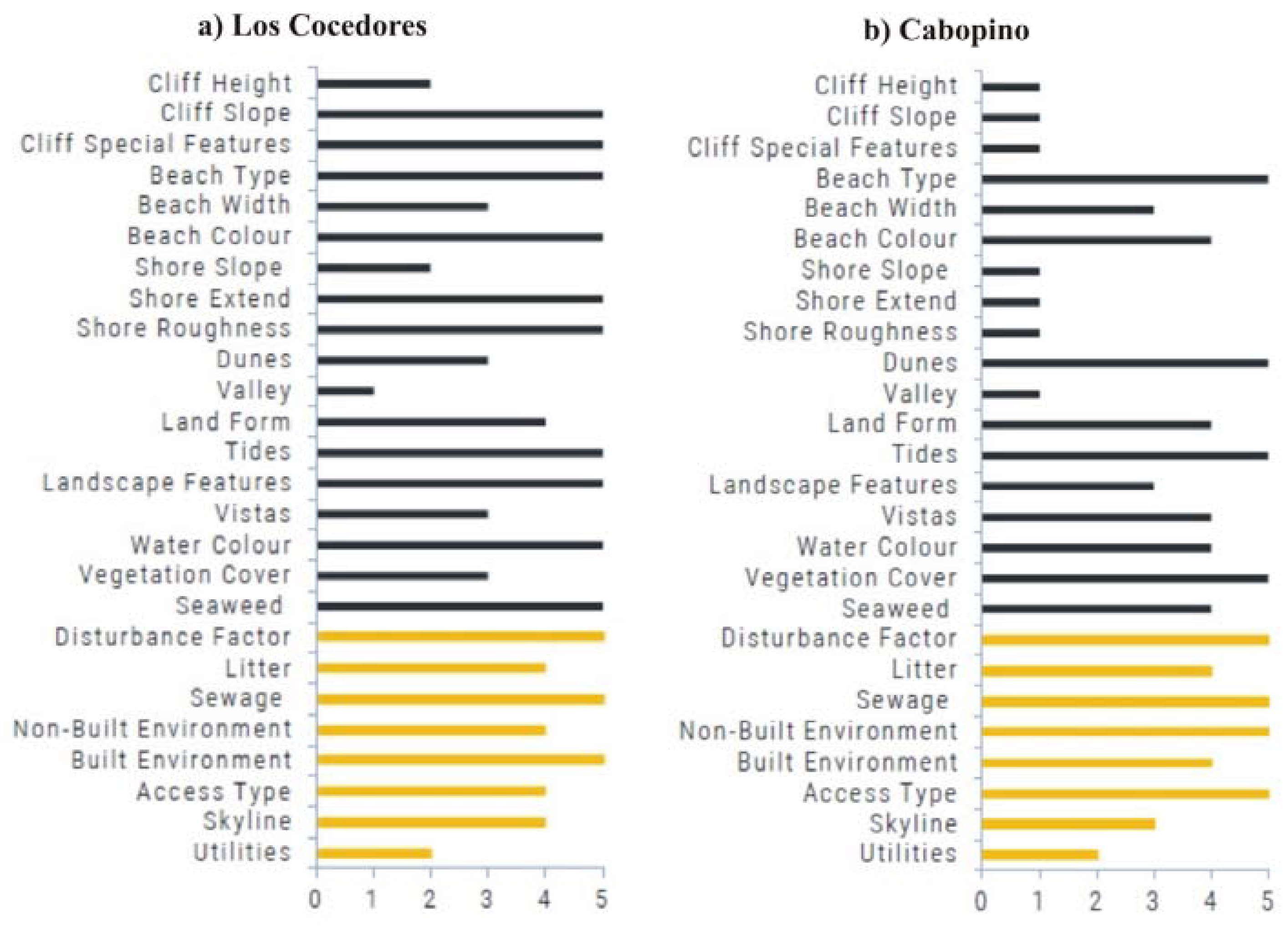

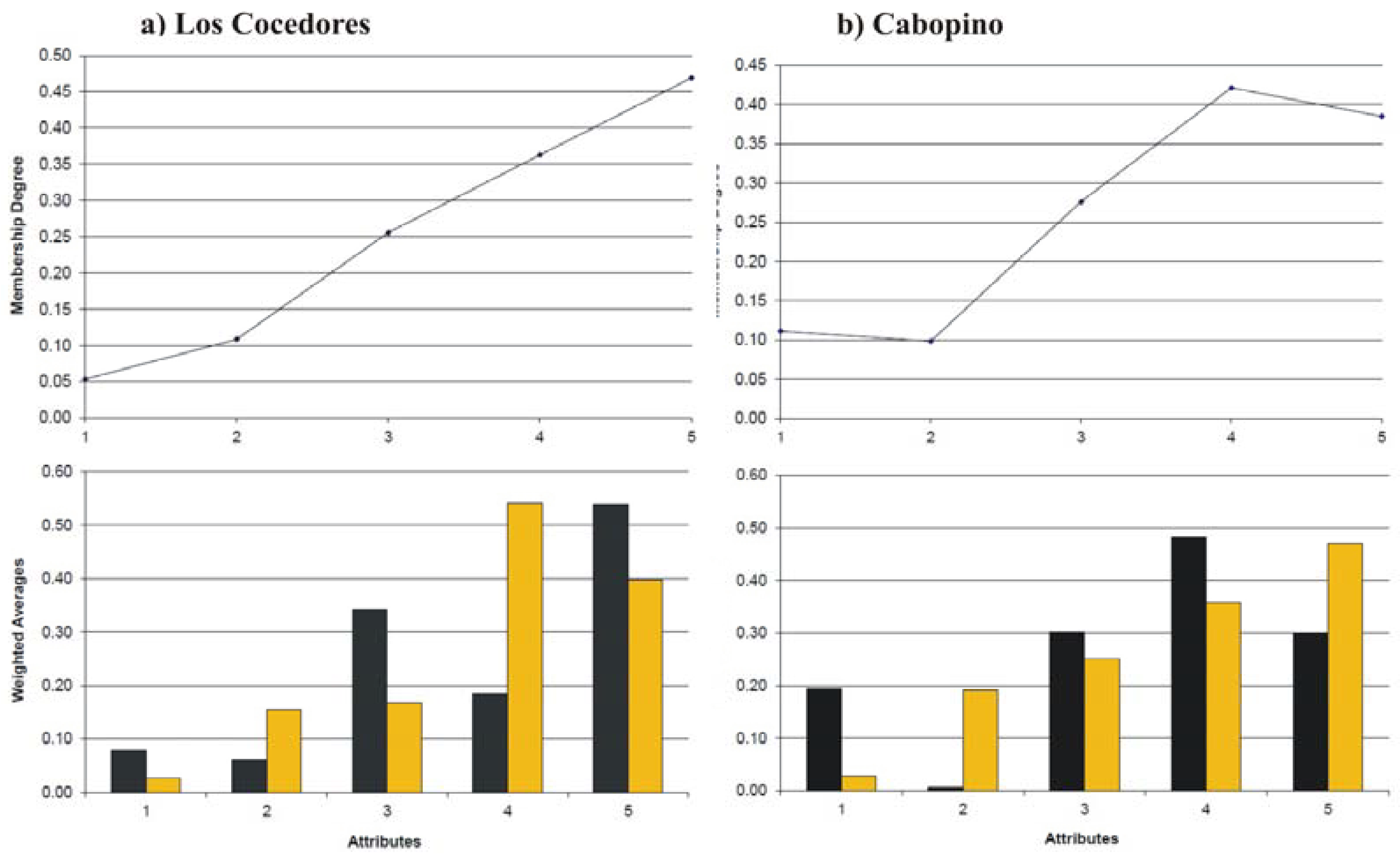

6.1. Natural and Human General Sites Characteristics

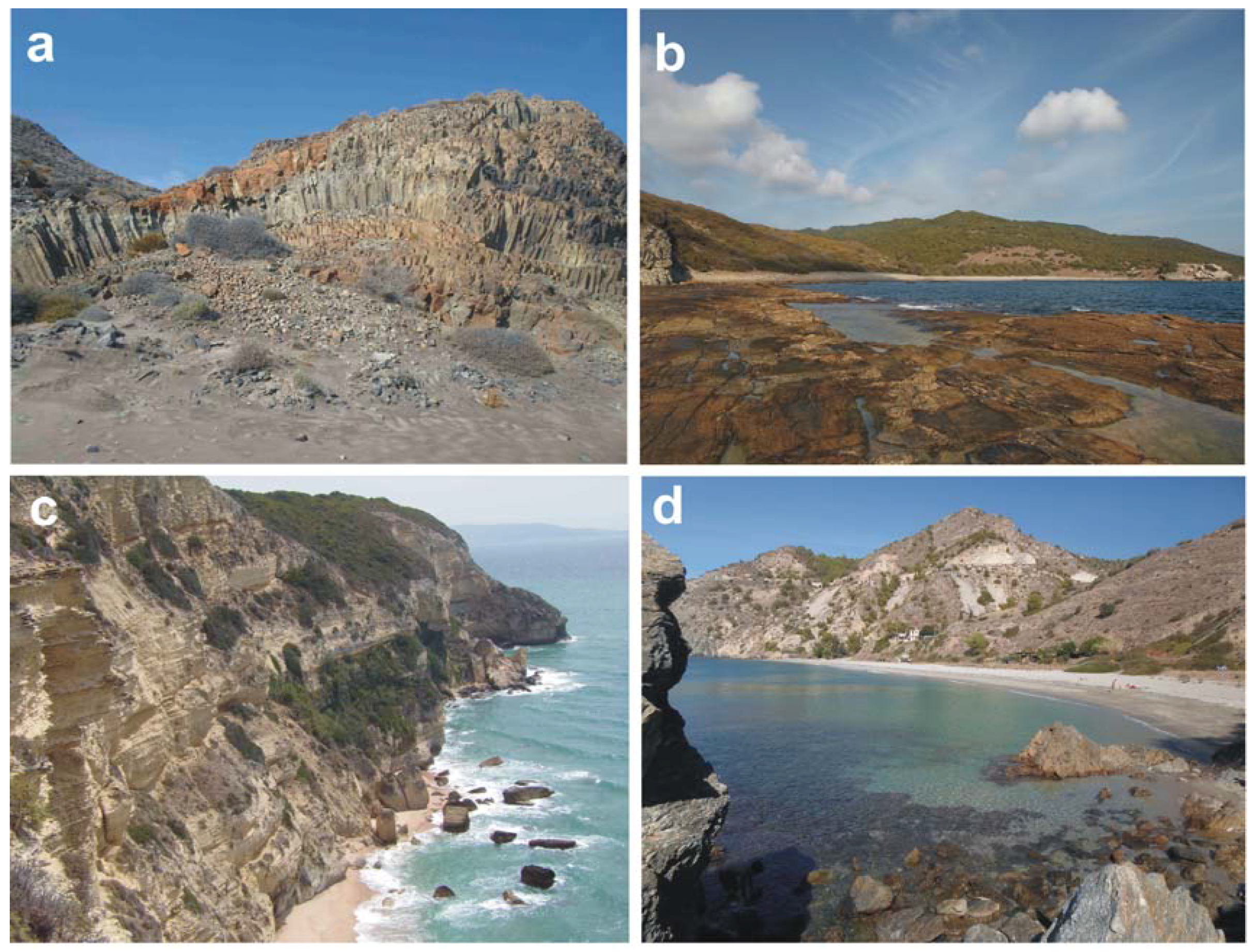

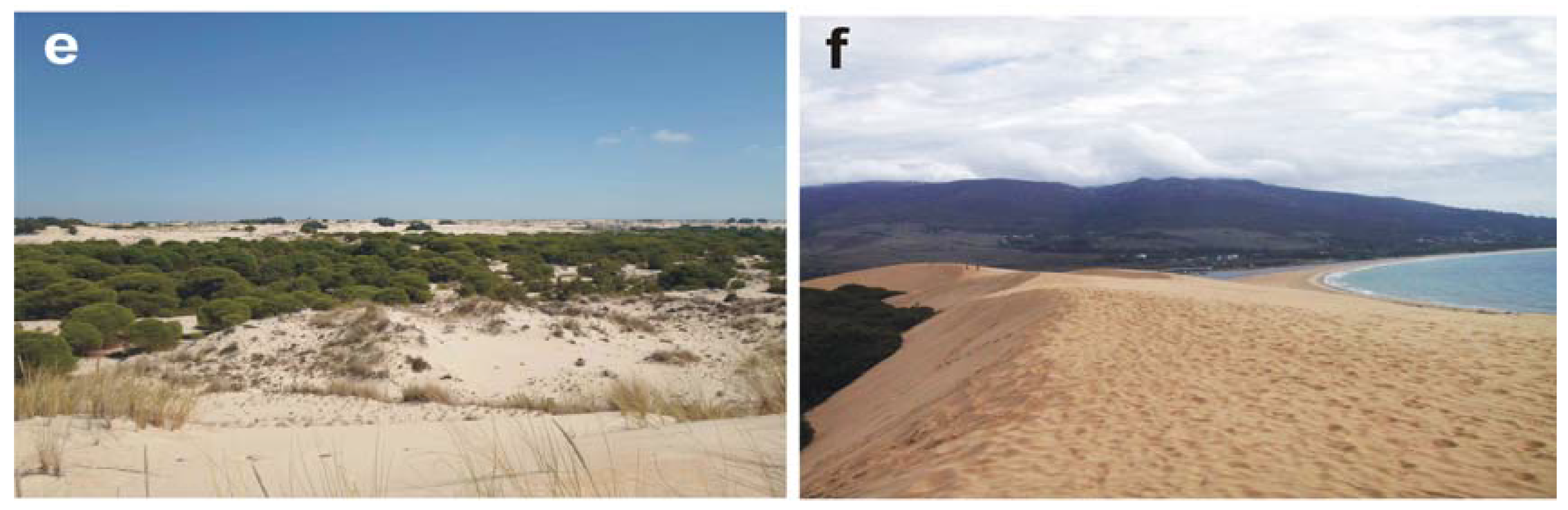

6.2. Examples of Class I and II sites

- (i)

- (ii)

- (iii)

- their location at the borders of protected areas; the skyline is not pristine and nearby human settlements are visible at Los Muertos and Lances Norte. From the former site is visible the industrial harbour of Carboneras and from the latter, human settlements at Tarifa (Table 4).

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

- (i)

- the intensive model, i.e., facilities provided are designed to give the minimum effect on the beauty of the protected area but facilitate maximum public enjoyment; and,

- (ii)

- remote, which retains areas in a relatively inaccessible and untouched state.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Doxey, G. A Causation Theory of Visitor–Resident Irritants: Methodology and Research Inferences. The Impact of Tourism. In The Sixth Annual Conference Proceedings; The Travel Research Association: San Diego, CA, USA, 1975; pp. 195–198. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R.W. The concept of the tourist area life-cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. Can. Geogr. 1980, 24, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, S. Economic linkages and impacts across the TALC. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 630–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagiewski, R. The Application of the Talc model: A literature survey. In Aspects of Tourism: The Tourism Area Life Cycle, Vol.1 Applications and Modifications; Butler, R., Ed.; Cromwell Press: Great Britain, UK, 2006; pp. 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- Leiper, N. Tourism Management; Arnold: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Leiper, N. Tourist Attraction Systems. A Model of Tourism Attractions. 1990. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZLYtGCEDkDw (accessed on 6 April 2018).

- Klein, Y.L.; Osleeb, J.P.; Viola, M.R. Tourism generated earnings in the coastal zone: A regional analysis. J. Coast. Res. 2004, 20, 1080–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). Tourism Highlights Edition; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2017; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Hannan, K.; Knox, D. Understanding Tourism. A Critical Introduction; SAGE: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, E. Overbooked: The Exploding Business of Travel and Tourism; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2013; p. 448. [Google Scholar]

- Benoit, G.; Comeau, A. A Sustainable Future for the Mediterranean: The Blue Plan’s Environment and Development Outlook; Earthscan: London, UK, 2005; p. 428. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, R.; Kelman, I. How climate change is considered in sustainable tourism policies: A case of the Mediterranean islands of Malta and Mallorca. Tour. Rev. Int. 2008, 12, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Energía, Turismo y Agenda Digital (MINETAD). Nota de Prensa: Balance del Sector Turístico 2016; MINETAD: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas (INE). Nota de Prensa: Encuesta de Turismo de Residentes (ETR/FAMILITUR). Cuarto Trimestre de 2016 y año 2016; INE: Mexico City, Mexico, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Consejería de Turismo y Deporte (CTD). Balance del Año Turístico 2016 en Andalucía; CTD: Sevilla, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Arenas, P. Gestión del litoral y política pública en España [Coastal Management and public policy in Spain]. In Manejo Costero Integrado y Política Pública en Iberoamérica: Un Diagnóstico; Barragán Muñoz, J.M., Ed.; Necesidad de cambio Red IBERMAR (CYTED): Cádiz, Spain, 2009; pp. 353–380. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, J.R. Coastal Zone Management Handbook; CRC Press/Lewis Publishers: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1996; p. 720. [Google Scholar]

- Houston, J.R. The economic value of beaches—A 2013 update. Shore Beach 2013, 81, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, M.; Liu, S. Non-market values of ecosystem services provided by coastal and nearshore and marine systems. In Ecological Economics of the Oceans and Coasts; Patterson, M., Glavovicic, B., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2008; p. 384. [Google Scholar]

- Ergin, A.; Karaesmen, E.; Micallef, A.; Williams, A.T. A new methodology for evaluating coastal scenery: Fuzzy logic systems. Area 2004, 36, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.T. Definitions and typologies of coastal tourism beach destinations. In Disappearing Destinations: Climate Change and Future Challenges for Coastal Tourism; Jones, A., Phillips, M., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2011; p. 296. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, A.T.; Micallef, A. Beach Management: Principles and Practices; Earthscan: London, UK, 2009; p. 480. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilo, E.; Alegre, J.; Sard, M. The persistence of the sun and sand tourism model. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton, D.L. The assessment of scenery as a natural resource. Scott. Geogr. Mag. 1968, 84, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, B.D.; Gilad, A.; Bisset, R.; Tomlinson, P. Perspectives in Environmental Impact Assessment; Springer: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Poon, A. Tourism, Technology and Competitive Strategies; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ergin, A.; Williams, A.T.; Micallef, A. Coastal scenery: Appreciation and evaluation. J. Coast. Res. 2006, 22, 958–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anfuso, G.; Williams, A.T.; Casas Martínez, G.; Botero, C.M.; Cabrera Hernández, J.A.; Pranzini, E. Evaluation of the scenic value of 100 beaches in Cuba: Implications for coastal tourism management. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2017, 142, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, R.A. Coastal Scenic Assessment of the North Canterbury Coast, New Zealand. Unpublished. Master’s Thesis, Univercity of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand, 2006; p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, Z.; Johnson, D.; Micallef, A.; Williams, A.T. From the Mediterranean to Pakistan and back—Coastal scenic assessment for tourism development in Pakistan. J. Coast. Conserv. Manag. 2010, 14, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.T.; Micallef, A.; Anfuso, G.; Gallego Fernández, J.B. Andalusia, Spain: An assessment of coastal scenery. Landsc. Res. 2012, 373, 327–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anfuso, G.; Williams, A.T.; Cabrera Hernández, J.A.; Pranzini, E. Coastal scenic assessment and tourism management in western Cuba. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.T.; Sellers, V.; Philips, M.R. An Assessment of UK Heritage Coasts in South Wales: J A Steers revisited. In Proceedings of the 9th International Coastal Symposium, Sunshine Coast, Australia, 20–24 August 2007; pp. 453–458, ISBN 0749.0208. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers. Chambers Dictionary; Chambers: Edinburg UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, A.T. The Concept of Scenic Beauty in a Landscape. In Coastal Scenery; Rangel-Buitrago, N., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Leopold, L.B. Quantitative Comparisons of Some Aesthetics Factors Among Rivers; US Geological Survey: Washington, DC, USA, 1969.

- Penning Rowsell, E.C. A public preference evaluation of landscape quality. Reg. Stud. 1982, 16, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The visual environment: Public participation in design and planning. Soc. Issues 1989, 45, 59–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Countryside Council for Wales (CCW). Annual Report, The Welsh Landscape: Our Inheritance and its Future Protection and Enhancement; CCW: Bangor, Wales, 1996.

- Countryside Council for Wales (CCW). The LANDMAP Information System, 1st ed.; CCW: Bangor, Wales, 2001.

- Macaulay. Review of Existing Methods of Landscape Assessment. 2014. Available online: www.macaulay.ac.uk/ccw/task-two/evaluate.html (accessed on 4 August 2016).

- Dupont, L.; Antrop, M.; Van Eetvelde, V. Does landscape related expertise influence the visual perception of landscape photographs? Implications for participatory landscape planning and management. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 141, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.T.; Lavalle, C.D. Coastal Landscape Evaluation and Photography. J. Coast. Res. 1990, 6, 1011–1020. [Google Scholar]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA). Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; p. 155. [Google Scholar]

- Chica Ruiz, J.A.; Pérez Cayeiro, M.L.; Barragán, J.M. La Evaluación de los ecosistemas del milenio en el litoral español y andaluz. Ambienta 2012, 98, 94–104. [Google Scholar]

- Barragán Muñoz, J.M. Política, Gestión y Litoral, una Nueva Visión de la Gestión Integrada de Áreas Litorales; Tebar Flores: Madrid, Spain, 2014; p. 688. [Google Scholar]

- Plan del Turismo Español Horizonte 2020. Ministerio de Industria, Turismo y Comercio. 2007. Available online: http://www.tourspain.es/eses/VDE/Documentos%20Vision%20Destino%20Espaa/Plan_Turismo_Espa%C3%B1ol_Horizonte_2020.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2018).

- Priskin, J. Assessment of natural resources for nature-based tourism: The case of the Central Coast Region of Western Australia. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, A. Managing Tourism at World Heritage Sites: A Practical Manual for World Heritage Site Managers; UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 2002; p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, Y.F.; Spenceley, A.; Hvenegaard, G.; Buckley, R. Tourism and Visitor Management in Protected Areas: Guidelines towards Sustainability. In Best Practice Protected Area Guideline; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Manno, G.; Anfuso, G.; Messina, E.; Williams, A.T.; Suffo, M.; Liguori, V. Decadal evolution of coastline armouring along the Mediterranean Andalusia littoral (South of Spain). Ocean Coast. Manag. 2016, 124, 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anfuso, G.; Rangel Buitrago, N.; Cortés Useche, C.; Iglesias Castillo, B.; Gracia, F.J. Characterization of storm events along the Gulf of Cadiz (eastern central Atlantic Ocean). Int. J. Climatol. 2016, 36, 3690–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Red de Espacios Naturales Protegidos de Andalucía (RENPA). Informe Actualizado de la Superficie RENPA (Mapa). Available online: http://www.juntadeandalucia.es/medioambiente/portal_web/web/temas_ambientales/espacios_protegidos/01_renpa/05_areas_protegidas/mapa_cartografia_renpa/2017_mapa_renpa.jpg (accessed on 6 February 2018).

- Chica Ruiz, J.A.; Barragan, J.M. Estado y Tendencia de los Servicios de los Ecosistemas Litorales de Andalucía; Consejería de Medio Ambiente: Sevilla, Spain, 2011; p. 112. [Google Scholar]

- Plan de Protección del Corredor Litoral de Andalucía (PPCA). Informe de Sostenibilidad de la Consejería de Agricultura; Pesca y Medio Ambiente: Sevilla, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Red de Información Ambiental de Andalucía (REDIAM). WBS (Web Map Services) Correspondiente a la Delimitación de la RENPA. Available online: http://www.juntadeandalucia.es/medioambiente/site/rediam (accessed on 6 February 2018).

- RENPA. Listado de las Áreas Protegidas Presentes en Andalucía. Available online: http://www.juntadeandalucia.es/medioambiente/site/portalweb/menuitem (accessed on 6 February 2018).

- Kaye, R.; Alder, J. Coastal Planning and Management; E & FN Spon: London, UK, 1999; p. 375. [Google Scholar]

- Steers, J.A. Coastal preservation and planning. Geog. J. 1944, 104, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teale, E.W. Wandering through Winter; Dodd, Mead and Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- British Council Report (BCR). Coastal Scenic Assessments at Selected Sites in Turkey, UK and Malta; Final Report; British Council Office: Ankara, Turkey; Valetta, Malta, 2003; p. 64. [Google Scholar]

- Eletheriadis, N.; Tsalikidis, I.; Manos, B. Coastal landscape preference evaluation. A comparison among tourists in Greece. Environ. Manag. 1990, 14, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dr Beach. Available online: www.drbeach.org/online/dr-beachs-50-criteria/ (accessed on 4 April 2018).

- Pranzini, E.; Anfuso, G.; Botero, C.; Cabrera, A.; Apin Campos, Y.; Casas Martinez, G.; Williams, A.T. Beach colour at Cuba and management issues. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2016, 126, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A. Analytical structures and analysis of fuzzy PD controllers with multifuzzy sets having variable cross-point level. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2002, 129, 311–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L. Fuzzy Sets. Inf. Control 1965, 8, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel-Buitrago, N.; Anfuso, G.; Correa, I.; Ergin, A.; Williams, A.T. Assessing and managing scenery of the Caribbean coast of Colombia. Tour. Manag. 2013, 35, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, B.; Anfuso, G.; Uterga, A.; Arenas, P.; Williams, A.T. Scenic value of the Basque Country and Catalonia coasts (Spain): Impacts of tourist occupation. J. Coast. Conserv. 2018, 22, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.; Stancheva, M.; Stanchev, H.; Palazov, A. Global lessons or future development along the Black sea coast of Bulgaria. In Proceedings of the Geological Society of America Annual Meeting, Denver, CO, USA, 27–30 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Marine Litter, an analytical overview. In UNEP Report; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2005; p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, A.T. Coastal conservation policy development in England and Whales with special reference to the Heritage Coast concept. J. Coast. Res. 1987, 3, 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Stancheva, M.; Stanchev, H.; Peev, P.; Anfuso, G.; Willliams, A.T. Coastal protected areas and historical sites in North Bulgaria—Challenges, mismanagement and future perspectives. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2016, 130, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botero, C.; Williams, A.T.; Cabrera, J.A. Advances in beach management in Latin America: An overview from certification schemes. In Environmental Management Governance: Advances in Coastal and Marine Resources, Coastal Research Library; Finkl, C.W., Makowski, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015; p. 472. [Google Scholar]

- Ariza, E.; Jiménez, A.J.; Sardá, R. Seasonal evolution of beach waste and litter during the bathing season on the Catalan coast. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 2604–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabrielides, G.; Golik, A.; Loizides, L.; Marino, M.; Bingel, F.; Torregrossa, M. Manmade garbage pollution on the Mediterranean coastline. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1991, 23, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galgani, F.; Leaute, J.P.; Moguedet, P.; Souplet, A.; Verin, Y.; Carpenter, A.; Goraguer, H.; Latrouite, D.; Andral, B.; Cadiou, Y.; et al. Litter on the sea floor along European coasts. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2000, 40, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maziane, F.; Nachite, D.; Anfuso, G. Artificial polymer materials debris characteristics along the Moroccan Mediterranean coast. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 128, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topçu, E.N.; Öztürk, B. Abundance and composition of solid waste materials on the western part of the Turkish Black Sea seabed. Aquat. Ecosyst. Health Manag. 2010, 13, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefatos, A.; Charalampakis, M.; Papatheodorou, G.; Ferentinos, G. Marine debris on the seafloor of the Mediterranean Sea: Examples from two enclosed gulfs in western Greece. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1999, 38, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliani, S.; Griffa, A.; Molcard, A. Floating debris in the Ligurian Sea, northwestern Mediterranean. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2003, 46, 1142–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeta, G.; Conti, L.; Malavasi, M.; Battisti, C.; Acosta, A.T.R. Beach litter occurrence in sandy littorals: The potential role of urban areas, rivers and beach users in central Italy. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2016, 181, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.T.; Randerson, P.; Di Giacomo, C.; Anfuso, G.; Macias, A.; Perales, J.A. Distribution of beach litter along the coastline of Cádiz, Spain. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 107, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coe, J.M.; Rogers, D.B. Marine Debris: Sources, Impacts and Solutions; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1997; p. 432. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Plastic Debris in the Ocean Emerging Issues in Our Global Environment. University of Surrey, 1987 The Public Health Implications of Sewage Pollution of Bathing Water Guildford: The Robens Institute of Industrial and Environmental Safety; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2011; p. 53. [Google Scholar]

- Anfuso, G.; Lynch, K.; Williams, A.T.; Perales, J.A.; Pereira da Silva, C.; Nogueira Mendes, R.; Maanan, M.; Pretti, C.; Pranzini, E.; Winter, C.; et al. Comments on Marine Litter in Oceans, Seas and Beaches: Characteristics and Impacts. Ann. Mar. Biol. Res. 2015, 2, 1008–1012. [Google Scholar]

- Krelling, A.; Williams, A.T.; Turra, A. Differences in perception and reaction of tourist groups to beach marine debris that can influence a loss of tourism revenue in coastal areas. Mar. Policy 2017, 85, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, C.; Pereira da Silva, C.; Calado, H.; Moniz, F.; Bragagnolo, C.; Gil, A.; Phillips, M.; Pereira, M.; Moreira, M. Coastal and marine protected areas as key elements for tourism in small islands. J. Coast Res. 2014, 70, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.T. Management strategies for coastal conservation in South Wales, U.K. In Recreational Uses of Coastal Areas; Fabbri, P., Ed.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Norwell, MA, USA, 1990; p. 285. [Google Scholar]

- Das, M.; Chatterjee, B. Ecotourism: A panacea or a predicament? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 14, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyman, S. High-end Ecotourism and Rural Communities in Southern Africa: A Socio-Economic Analysis. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.E.; Doh, M.; Park, S.; Chon, J. Transformation Planning of Ecotourism Systems to Invigorate Responsible Tourism. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stem, C.J.; Lassoie, J.P.; Lee, D.R.; Deshler, D.D.; Schelhas, J.W. Community participation in ecotourism benefits: The link to conservation practices and perspectives. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2003, 16, 387–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D. Destination communities and responsible tourism. In Responsible Tourism: Concepts, Theory and Practice; Leslie, D., Ed.; CABI: Oxfordshire, UK, 2012; p. 77. [Google Scholar]

| MAP NUMBER & SITE | P | PROTECTION FEATURE | A.D.* | CLASS | D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. La Casita Azul | Huelva | None | 1 | II | 0.77 |

| 2. Los Enebrales | Natural Place Los Enebrales | 5 | I | 0.86 | |

| 3. Flecha del Rompido | Natural Place Flecha del Rompido, SCI, SPA | 2 | I | 1.13 | |

| 4. Torre del Loro | Natural Park Doñana, BR, SAC, SPA, NM | 3 | I | 1.07 | |

| 5. Cuesta Maneli | Natural Park Doñana, BR, SAC, SPA, NM | 3 | I | 0.95 | |

| 6. Laguna del Jaral | Natural Park Doñana, BR, SAC, SPA, NM | 5 | I | 1.01 | |

| 7. Torre Carbonero | WHS, National Park Doñana, BR, SAC, SPA, MN | 5 | I | 1.05 | |

| 8. Punta del Boqueron | Cadiz | Natural Park Bahía de Cadiz, SAC, SPA, NM | 3 | I | 0.98 |

| 9. Playa del Puerco | Monte Público Dehesa de Roche ** | 2 | I | 1.02 | |

| 10. Calas de Roche | SAC Pinar de Roche | 2 | I | 0.95 | |

| 11. Castilnovo | Complejo Litoral de Interés Ambiental ** | 4 | I | 0.9 | |

| 12. Tombolo de Trafalgar | SAC Punta de Trafalgar, NM | 3 | I | 1.09 | |

| 13. Cala de Las Cortinas | Natural Park La Breña de Barbate, SAC, SPA | 5 | I | 1.15 | |

| 14. La Hierbabuena | Natural Park La Breña de Barbate, SAC, SPA | 1 | I | 0.96 | |

| 15. El Cañuelo | Natural Park Estrecho de Gibraltar, IMBR, SAC, SPA | 4 | I | 1.23 | |

| 16. Bolonia | Natural Park Estrecho de Gibraltar, IMBR, SAC, SPA | 2 | I | 1.11 | |

| 17. El Lentiscal | Natural Park Estrecho de Gibraltar, IMBR, SAC, SPA | 3 | I | 1.09 | |

| 18. Punta de la Morena | Natural Park Estrecho de Gibraltar, IMBR, SAC, SPA | 4 | I | 1.05 | |

| 19. El Chorrito de la Teja | Natural Park Estrecho de Gibraltar, IMBR, SAC, SPA | 4 | I | 1.06 | |

| 20. Valdevaqueros | Natural Park Estrecho de Gibraltar, IMBR, SAC, SPA | 1 | I | 0.91 | |

| 21. Lances Norte | Natural Place Estrecho de Gibraltar, IMBR, SAC, SPA | 3 | II | 0.8 | |

| 22. Ensenada del Tolmo | Natural Park Estrecho de Gibraltar, IMBR, SAC, SPA | 5 | II | 0.84 | |

| 23. Cala Arena | Natural Park Estrecho de Gibraltar, IMBR, SAC, SPA | 4 | I | 0.91 | |

| 24. Cabopino | Malaga | NM Dunas de Artola | 1 | II | 0.73 |

| 25. Punta de Vélez | None | 2 | II | 0.77 | |

| 26. Caleta de Maro | Natural Place Maro-CG, SPAMI, SAC, SPA | 3 | II | 0.84 | |

| 27. Cala Chumbo | Natural Place Maro-CG, SPAMI, SAC, SPA | 5 | I | 1.02 | |

| 28. Las Alberquillas | Natural Place Maro-CG, SPAMI, SAC, SPA | 3 | I | 0.95 | |

| 29. Calas del Pino | Natural Place Maro-CG, SPAMI, SAC, SPA | 3 | I | 0.95 | |

| 30. Cala el Cañuelo | Natural Place Maro-CG, SPAMI, SAC, SPA | 3 | I | 0.9 | |

| 31. Cantarrijan | Granada | Natural Place Maro-CG, SPAMI, SAC, SPA | 2 | I | 1.07 |

| 32. Cala El Cambron | SAC Acantilados y Fondos marinos de Tesorillo-Salobreña | 3 | II | 0.68 | |

| 33. La Rijana | SAC Acantilados y F. Marinos Calahonda | 2 | I | 0.89 | |

| 34. El Ruso | None | 4 | I | 0.96 | |

| 35. Punta Sabinar | Almeria | Natural Place Punta Entinas-Sabinar, SCI, SPA | 4 | II | 0.82 |

| 36. Cala Arena | Natural Park Cabo de Gata-Nijar, BR, SPAMI, SAC, SPA, EGN | 3 | I | 0.96 | |

| 37. Cala Raja | Natural Park Cabo de Gata-Nijar, BR, SPAMI, SAC, SPA, EGN | 3 | I | 1.04 | |

| 38. Cala de la Media Luna | Natural Park Cabo de Gata-Nijar, BR, SPAMI, SAC, SPA, EGN | 2 | I | 1.01 | |

| 39. Monsul | Natural Park Cabo de Gata-Nijar, BR, SPAMI, SAC, SPA, EGN | 2 | I | 1.19 | |

| 40. Barronal | Natural Park Cabo de Gata-Nijar, BR, SPAMI, SAC, SPA, EGN | 3 | I | 1.03 | |

| 41. Cala Grande | Natural Park Cabo de Gata-Nijar, BR, SPAMI, SAC, SPA, EGN | 4 | I | 1.09 | |

| 42. Los Genoveses | Natural Park Cabo de Gata-Nijar, BR, SPAMI, SAC, SPA, EGN | 2 | I | 1.26 | |

| 43. El Playazo | Natural Park Cabo de Gata-Nijar, BR, SPAMI, SAC, SPA, EGN | 2 | I | 1.12 | |

| 44. Cala de San Pedro | Natural Park Cabo de Gata-Nijar, BR, SPAMI, SAC, SPA, EGN | 5 | I | 0.85 | |

| 45. Cala del Plomo | Natural Park Cabo de Gata-Nijar, BR, SPAMI, SAC, SPA, EGN | 2 | I | 0.91 | |

| 46. Cala de Enmedio | Natural Park Cabo de Gata-Nijar, BR, SPAMI, SAC, SPA, EGN | 4 | I | 1.2 | |

| 47. Los Muertos | Natural Park Cabo de Gata-Nijar, BR, SPAMI, SAC, SPA, EGN | 3 | I | 0.93 | |

| 48. El Sombrerico | SAC Sierra Cabrera-Bedar, SPAMI Fondos mar. lev. almeriense | 2 | I | 0.88 | |

| 49. Bordenares | SAC Sierra Cabrera-Bedar, SPAMI Fondos mar. lev. almeriense | 2 | I | 0.94 | |

| 50. Los Cocedores | None, marine area protected as SPAMI | 1 | II | 0.83 |

| No. | PARAMETERS | RATING | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| 1 | Height (H) | Absent | 5 m ≤ H < 30 m | 30 m ≤ H < 60 m | 60 m ≤ H < 90 m | H ≥ 90 m | |

| 2 | CLIFF | Slope | <45° | 45°–60° | 60°–75° | 75°–85° | circa vertical |

| 3 | Features * | Absent | 1 | 2 | 3 | Many (>3) | |

| 4 | Type | Absent | Mud | Cobble/Boulder | Pebble/Gravel | Sand | |

| 5 | BEACH FACE | Width (W) | Absent | W <5 m or W >100 m | 5 m ≤ W < 25 m | 25 m ≤ W < 50 m | 50 m ≤ W ≤ 100 m |

| 6 | Colour | Absent | Dark | Dark tan | Light tan/bleached | White/gold | |

| 7 | Slope | Absent | <5° | 5°–10° | 10°–20° | 20°–45° | |

| 8 | ROCKY SHORE | Extent | Absent | <5 m | 5–10 m | 10–20 m | >20 m |

| 9 | Roughness | Absent | Distinctly jagged | Deeply pitted and/or irregular | Shallow pitted | Smooth | |

| 10 | DUNES | Absent | Remnants | Fore-dune | Secondary ridge | Several | |

| 11 | VALLEY | Absent | Dry valley | (<1 m) Stream | (1–4 m) Stream | River/limestone gorge | |

| 12 | SKYLINE LANDFORM | Not visible | Flat | Undulating | Highly undulating | Mountainous | |

| 13 | TIDES | Macro (>4 m) | Meso (2–4 m) | Micro (<2 m) | |||

| 14 | COASTAL LANDSCAPE FEATURES ** | None | 1 | 2 | 3 | >3 | |

| 15 | VISTAS | Open on one side | Open on two sides | Open on three sides | Open on four sides | ||

| 16 | WATER COLOUR & CLARITY | Muddy brown/grey | Milky blue/green/opaque | Green/grey/blue | Clear blue/dark blue | Very clear turquoise | |

| 17 | NATURAL VEGETATION COVER | Bare (<10% vegetation only) | Scrub/garigue (marran/gorse, bramble, etc.) | Wetlands/meadow | Coppices, maquis (±mature trees) | Varity of mature trees/mature natural cover | |

| 18 | VEGETATION DEBRIS | Continuous (>50 cm high) | Full strand line | Single accumulation | Few scattered items | None | |

| 19 | NOISE DISTURBANCE | Intolerable | Tolerable | Little | None | ||

| 20 | LITTER | Continuous accumulations | Full strand line | Single accumulation | Few scattered items | Virtually absent | |

| 21 | SEWAGE DISCHARGE EVIDENCE | Sewage evidence | Same evidence (1–3 items) | No evidence of sewage | |||

| 22 | NON_BUILT ENVIRONMENT | None | Hedgerow/terracing/monoculture | Field mixed cultivation ± trees/natural | |||

| 23 | BUILT ENVIRONMENT *** | Heavy Industry | Heavy tourism and/or urban | Light tourism and/or urban and/or sensitive | Sensitive tourism and/or urban | Historic and/or none | |

| 24 | ACCESS TYPE | No buffer zone/heavy traffic | No buffer zone/light traffic | Parking lot visible from coastal area | Parking lot not visible from coastal area | ||

| 25 | SKYLINE | Very unattractive | Sensitively designed high/low | Very sensitively designed | Natural/historic features | ||

| 26 | UTILITIES **** | >3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | None | |

| No. | Assessment Parameters | Graded Attributes | Weights of Parameters | Input Matrices di | Fuzzy Assessment Matrices | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G Matrices | Grade Matrices Gi | R Matrices | Fuzzy Weighted Assessment Matrix Rm | ||||||||||||||||||

| Attributes (1–5) | Attributes (1–5) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Cliff Height | 2 | 0.019 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.019 | 0.006 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| 2 | Cliff Slope | 3 | 0.017 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.009 | 0.017 | 0.009 | 0.000 | |||

| 3 | PHYSICAL | Special Features | 4 | 0.028 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | GP | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.30 | RP | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.028 | 0.008 |

| 4 | Beach Type | 5 | 0.034 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.034 | |||

| 5 | Beach Width | 4 | 0.029 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 1.00 | 0.60 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.006 | 0.029 | 0.017 | |||

| 6 | Beach Color | 5 | 0.024 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.024 | |||

| 7 | Shore Slope | 1 | 0.014 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.014 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| 8 | Shore Extent | 1 | 0.015 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.015 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| 9 | Shore roughness | 1 | 0.022 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.022 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| 10 | Dunes | 5 | 0.039 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.039 | |||

| 11 | Valley | 1 | 0.079 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.079 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| 12 | Landform | 1 | 0.085 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.085 | 0.017 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| 13 | Tides | 3 | 0.036 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.036 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| 14 | Landscape Features | 4 | 0.122 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.20 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.121 | 0.024 | |||

| 15 | Vistas | 4 | 0.095 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.30 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.095 | 0.029 | |||

| 16 | Water Color | 4 | 0.139 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.20 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.070 | 0.140 | 0.028 | |||

| 17 | Vegetation Cover | 4 | 0.117 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 1.00 | 0.20 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.023 | 0.117 | 0.023 | |||

| 18 | Seaweed | 4 | 0.086 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.017 | 0.086 | 0.000 | |||

| 19 | HUMAN | Disturbance Factor | 5 | 0.137 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | GH | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 1.00 | RH | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.027 | 0.137 |

| 20 | Litter | 3 | 0.149 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 1.00 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.030 | 0.149 | 0.030 | 0.000 | |||

| 21 | Sewage | 5 | 0.149 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.030 | 0.000 | 0.149 | |||

| 22 | Non-built Environment | 5 | 0.064 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.013 | 0.000 | 0.064 | |||

| 23 | Built Environment | 5 | 0.137 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.137 | |||

| 24 | Access Type | 5 | 0.091 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 1.00 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.018 | 0.091 | |||

| 25 | Skyline | 5 | 0.137 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.137 | |||

| 26 | Utilities | 5 | 0.137 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 1.00 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.027 | 0.137 | |||

| INVESTIGATED SITES | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. | HUELVA | CADIZ | MALAGA | GRANADA | ALMERIA | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| P.A | Doñana | Gibraltar Strait | Maro-Cerro G | Cabo de Gata-Nijar | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Casita Azul | Flecha del Rompido | Los Enebrales | Torre del Loro | Cuesta Maneli | Laguna del Jaral | Torre Carbonero | Punta del Boquerón | Playa del Puerco | Calas de Roche | Castilnovo | Tómbolo Trafalgar | Cala de Las Cortinas | La Hierbabuena | El Cañuelo | Bolonia | El Lentiscal | Punta de la Morena | El Chorrito de la Teja | Valdevaqueros | Lances Norte | Ensenada del Tolmo | Cala Arena | Cabopino | Punta de Vélez | Caleta de Maro | Cala Chumbo | Las Alberquillas | Calas del Pino | Cala el Cañuelo | Cantarrijan | Cala El Cambrón | La Rijana | El Ruso | Punta Sabinar | Cala Arena | Cala Raja | Cala Media Luna | Mónsul | Barronal | Cala Grande | Los Genoveses | El Playazo | Cala de San Pedro | Cala del Plomo | Cala de Enmedio | Los Muertos | El Sombrerico | Bordenares | Los Cocedores | ||

| Physical parameters | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | |

| 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | |

| 5 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 5 | |

| 9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 5 | |

| 10 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| 11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 12 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| 13 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| 14 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 5 | |

| 15 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| 16 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| 17 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | |

| 18 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | |

| Human parameters | 19 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 20 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| 21 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| 22 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | |

| 23 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | |

| 24 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 | |

| 25 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 4 | |

| 26 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 2 | |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mooser, A.; Anfuso, G.; Mestanza, C.; Williams, A.T. Management Implications for the Most Attractive Scenic Sites along the Andalusia Coast (SW Spain). Sustainability 2018, 10, 1328. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10051328

Mooser A, Anfuso G, Mestanza C, Williams AT. Management Implications for the Most Attractive Scenic Sites along the Andalusia Coast (SW Spain). Sustainability. 2018; 10(5):1328. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10051328

Chicago/Turabian StyleMooser, Alexis, Giorgio Anfuso, Carlos Mestanza, and Allan Thomas Williams. 2018. "Management Implications for the Most Attractive Scenic Sites along the Andalusia Coast (SW Spain)" Sustainability 10, no. 5: 1328. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10051328

APA StyleMooser, A., Anfuso, G., Mestanza, C., & Williams, A. T. (2018). Management Implications for the Most Attractive Scenic Sites along the Andalusia Coast (SW Spain). Sustainability, 10(5), 1328. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10051328