Can the SDGs Provide a Basis for Supply Chain Decisions in the Construction Sector?

Abstract

1. Introduction

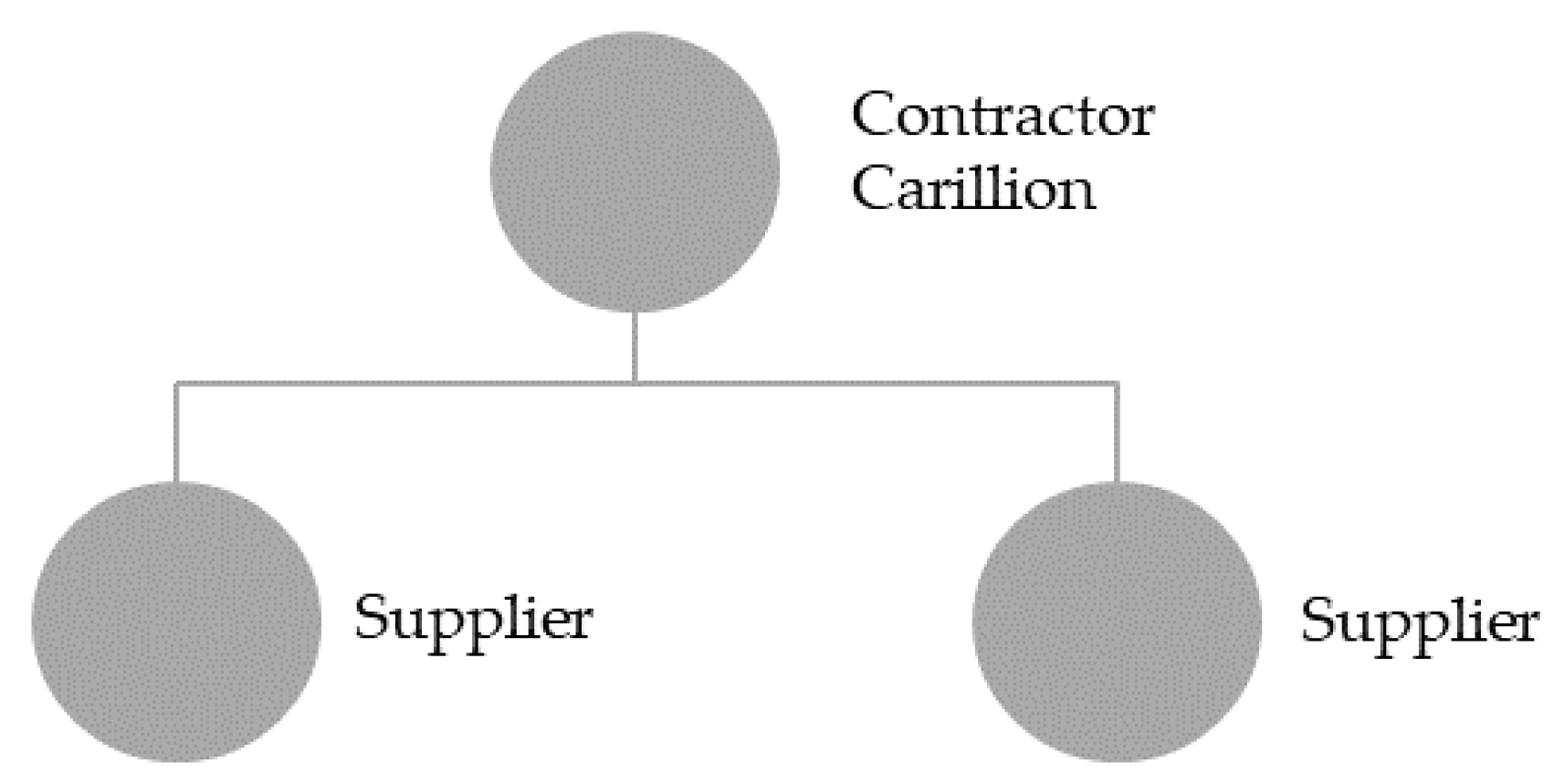

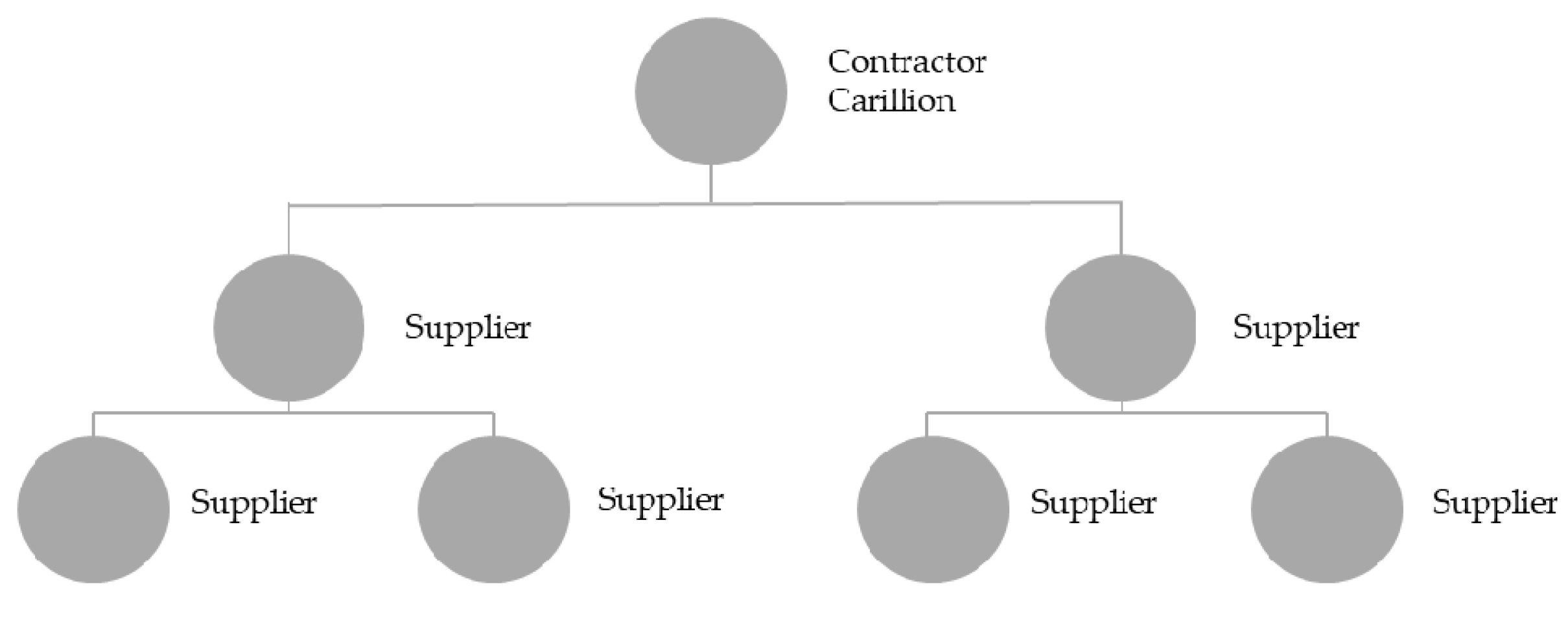

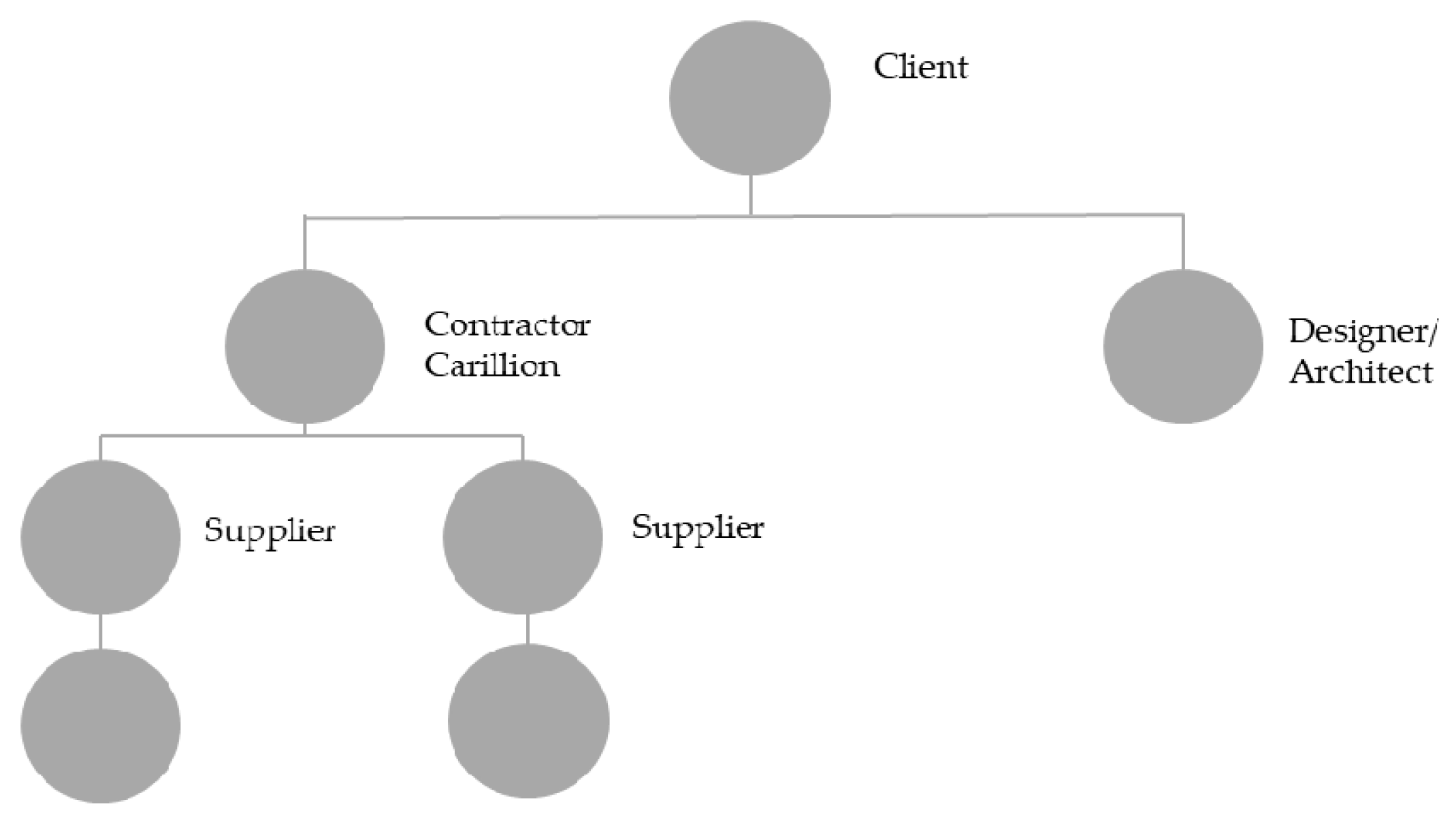

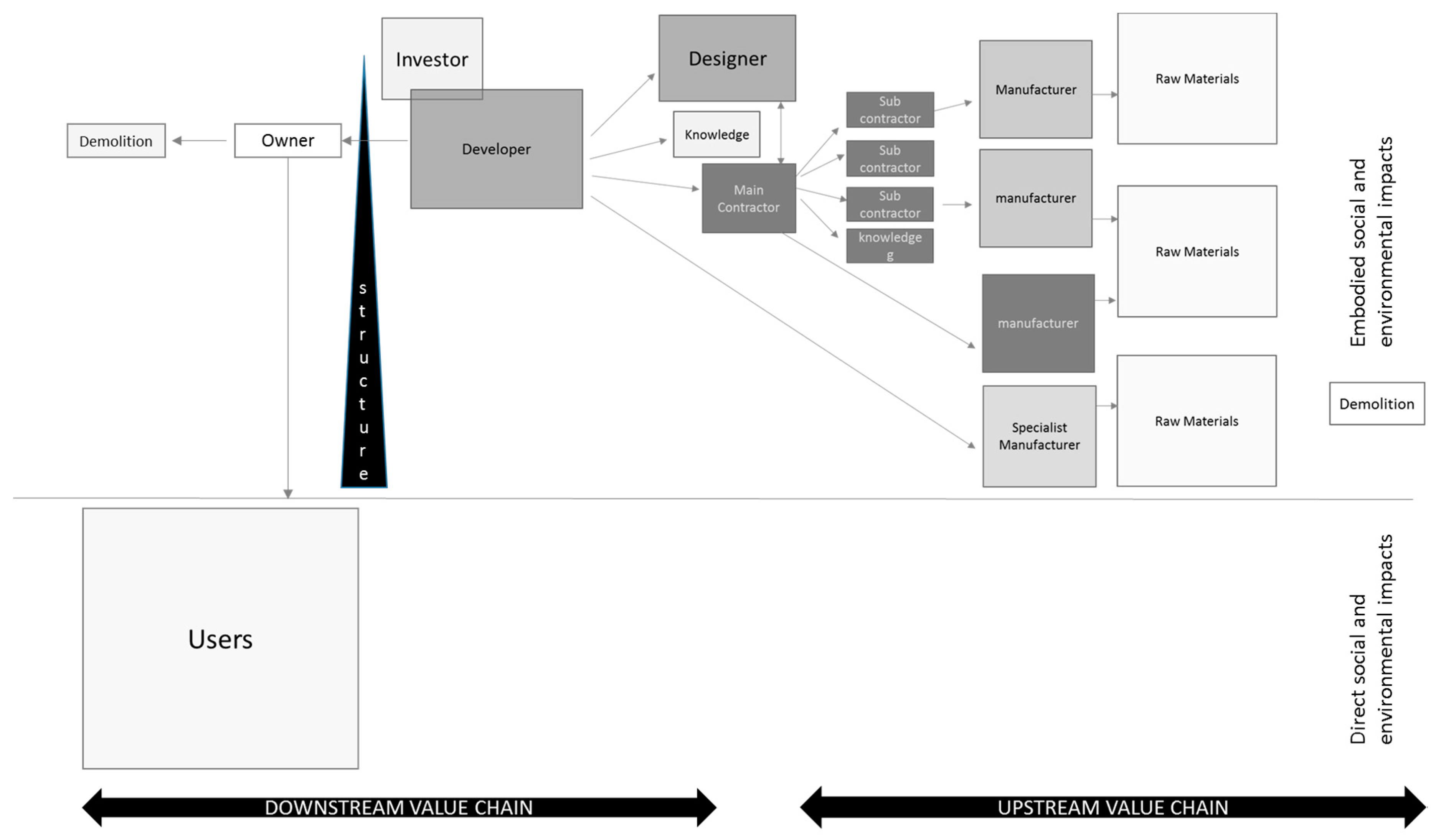

1.1. Construction and a Sustainable Supply Network

1.2. Sustainable Development Goals

1.3. Responsible Consumption and Production

2. Selection and Exploration of Approaches to Embedding the SDGs

2.1. Methodology

2.2. “Bottom-up” Goal Setting: Forest Stewardship Certification

2.3. Top-down Goal Setting: Modern Slavery

3. Observations and Comparisons

4. Operationalising the SDGs—Value Driven Approaches

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Semi Structured Orientation Interview Questions

- Please could you outline your role and how this fits within the supply chain (SC) team.

- How do you select suppliers and monitor supplier performance?

- What typically is the relationship/communication routes that the SC team have with suppliers?

- How far down the chain do you think Carillion have direct or indirect influence currently?

- When you report KPIs for Carillion, how far down the chain do you report?

- What do you think suppliers understand about sustainability? (Does it matter? to whom)

- When, as part of tendering process, is Sustainability flagged as an important criterion?

- If you talk to suppliers what do you say are the key sustainability goals that Carillion are looking to achieve through their work.

- How do you keep up to date with the company’s sustainability objectives/goals?

- If suppliers don’t know about sustainability where do you suggest they go if they want help?

- Can suppliers respond to requests for more innovative approaches/more sustainable approaches? (prompt: Examples of success)

- What do you think are the big barriers/issues that need to be turned into opportunities?

Appendix B. Sustainable Development Goals Supported by FSC

| SDGs Supported | SDG Targets Supported |

|---|---|

| Primary Goal | |

| 15. Life on Land | Main Target: 15.2 By 2020, promote the implementation of sustainable management of all types of forests, halt deforestation, restore degraded forests and substantially increase afforestation and reforestation globally |

| Secondary Targets: | |

| 15.1, 15.3, 15.4, 15.5, 15.7, 15.8, 15.c | |

| Additional Goals | |

| 1. No Poverty | 1.5 |

| 2. Zero Hunger | 2.4 |

| 5. Gender Equality | 5.5, 5.a |

| 6. Clean water and sanitation | 6.4, 6.5, 6.6, 6.7 |

| 7. Affordable and clean energy | 7.2 |

| 8. Decent work and economic growth | 8.4, 8.5, 8.7, 8.8, |

References

- Oxford Economics. Global Construction 2025; Oxford Economics: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Independent Police Complaints Council (IPCC). Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Edenhofer, O., Pichs-Madruga, R., Sokona, Y., Farahani, E., Kadner, S., Seyboth, K., Adler, A., Baum, I., Brunner, S., Eickemeier, P., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Buildings and Climate Change: Summary for Decision Makers; United Nations Environmental Programme—Sustainable Buildings and Climate Initiative: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Green, S. The evolution of corporate social responsibility in construction. In Corporate Social Responsibility in the Construction Industry; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cherns, A.; Bryant, D. Studying the client’s role in construction management. Constr. Manag. Econ. 1984, 2, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carillion. A Better Tomorrow: Sustainability Report 2015. Wolverhampton: Carillion plc. 2016. Available online: http://sustainability2015.carillionplc.com/assets/files/carillion-sr2015-full.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2017). (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6xBZOaUQ0).

- Scholman, H.S.A. Uitbesteding Door Hoofdaannemers (Subcontracting by Main Contractors); Economisch Instituut Voor de Bouwnijverheid: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Korczynski, M. The low-trust route to economic development: Inter-firm relations in the UK engineering construction industry in the 1980s and 1990s. J. Manag. Stud. 1996, 33, 787–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akitoye, A.; Mcintosh, G.; Fitzgerald, E. A survey of supply chain collaboration and management in the UK construction industry. Eur. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2000, 6, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Economist. Where Did Carillion Go Wrong? Available online: https://www.economist.com/news/britain/21735047-mistakes-caused-mega-contractors-demise-are-common-outsourcing-industry-where (accessed on 18 January 2018). (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6xBXBdihE).

- King, A.P.; Pitt, M.C. Supply chain management: A main contractors perspective. In Construction Supply Chain Management: Concepts and Case Studies; Pryke, S., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 189–192. [Google Scholar]

- Saad, M.; Jones, M.; James, P. A review of the progress towards the adoption of supply chain management (SCM) relationships in construction. Eur. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2002, 8, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briscoe, G.; Dainty, A. Construction supply chain integration: An elusive goal? Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2005, 10, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skitmore, M.; Smyth, H. Marketing and pricing Strategy. In Construction Supply Chain Management Concepts and Case Studies; Pryke, S., Ed.; Wiley Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, E.F. Investigation into the Use of Main Contractor Category Management to Improve Sustainability within the Construction Supply Network. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Surrey, Guildford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bank for International Settlements (BIS). Industrial Strategy: Industry and Government in Partnership: Construction 2025; HMSO: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett, S.E.; Magnum, G.M. The rhetoric and reality of supply chain integration. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2002, 32, 339–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vurro, C.; Russo, A.; Perrrini, F. Shaping sustainable value chains: Network determinants of supply chain governance models. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 90, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernie, S.; Tennant, S. The non-adoption of supply chain management. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2013, 31, 1038–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nystrom, J. Partnering: Definition, Theory and Evaluation. Ph.D. Thesis, Royal Institute of Technology (KTH), Stockholm, Sweden, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkhoff, A.; Thonemann, U.W. Perfekte Projekte in der Lieferkette. Harv. Bus. Manag. 2007, 7, 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Clift, R.; Sim, S.; Sinclair, P. Sustainable consumption and production: Quality, luxury and supply chain equity. In Treatise in Sustainability Science and Engineering; Jawahir, I.S., Sikhdar, S., Huang, Y., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 291–309. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, L.; Bourlakis, M. The evolution from corporate social responsibility to supply chain responsibility: The case of Waitrose. Supply Chain Manag. 2009, 14, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, G. Construction and Resources Roadmap; BRE Report Prepared for DEFRA’s Business Waste and Resource Efficiency Programme (BREW); BRE: Watford, UK, 2008; Available online: https://www.bre.co.uk/filelibrary/pdf/rpts/waste/Roadmap_final.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2017).

- WRAP. Current Practices and Future Potential in Modern Methods of Construction, Ref WAS003-001. 2007. Available online: http://www.wrap.org.uk/sites/files/wrap/Modern%20Methods%20of%20Construction%20Full.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2018). (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6xBXNwYDo).

- HM Government. UK Annual Report on Modern Slavery. 2017. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/652366/2017_uk_annual_report_on_modern_slavery.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2017)(Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6xBXZdy7I).

- Walk Free Foundation. The Global Slavery Index 2016; The Minderoo Foundation Pty Ltd.: Dalkeith, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. Global Estimates of Modern Slavery: Forced Labour and Marriage. 19 September 2017. Available online: http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/documents/publication/wcms_575479.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2017). (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6xBXiAzXF).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. A/RES/70/1; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, T. Keeping out the giraffes. In Long Horizons; Tickell, A., Ed.; British Council: London, UK, 2010; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Globescan. Evaluating Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals. Globescan/Sustainability Survey; Globescan: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UN. United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, Sustainable Development Agenda. 2015. Available online: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/development-agenda/ (accessed on 9 January 2018). (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6xBXp5g2H).

- Environmental Audit Committee. Sustainable Development Goals in the UK; House of Commons: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ethical Corp. Sustainability in Europe—Top Trends; Ethical Corporation: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, A.; Chapin, F.S., III; Lambin, E.F.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; Vries, W.D.; de Wit, C.A.; et al. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 2015, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clift, R.; Sim, S.; King, H.; Chenoweth, J.L.; Christie, I.; Clavreul, J.; Mueller, C.; Posthuma, L.; Boulay, A.M.; Chaplin-Kramer, R.; et al. The challenges of applying planetary boundaries as a basis for strategic decision-making in companies with global supply chains. Sustainability 2017, 9, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clift, R. Metrics for Supply Chain Sustainability. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2003, 5, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine Publishing Company: Hawthorne, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, N.; Stoneman, P. Researching Social Life, 4th ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Carillion. Sustainability Report 2014: Our Business. Wolverhampton: Carillion plc. 2015. Available online: http://sustainability2014.carillionplc.com/assets/files/carillion-sr2014-full.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2017). (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6xBZ8AZCh).

- Sandelowski, M. Qualitative analysis: What it is and how to begin. Res. Nurs. Health 1995, 18, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Union. Council Regulation (EU) No. 995/2010 Laying down the obligations of operators who place timber and timber products on the market. Off. J. Eur. Union 2010, 53, 23–34. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L:2010:295:FULL&from=EN (accessed on 12 September 2017).

- Strauss, A. Qualitative Analysis for Social Scientists; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.; VanWynsberghe, R. Cultivating the Under-Mined: Cross-Case Analysis as Knowledge Mobilization. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, [S.l.]. 2008, Volume 9. Available online: http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/334/729 (accessed on 18 February 2018).

- Murphy, D.F.; Bendell, J. Do-it yourself or do-it together? The implementation of sustainable timber purchasing policies by DIY retailers in the UK. In Greener Purchasing: Opportunities and Innovations; Russel, T., Ed.; Greenleaf Publishing: Sheffield, UK, 1998; pp. 118–134. [Google Scholar]

- FSC. The 10 FSC Principles. 2017. Available online: http://www.fsc-uk.org/en-uk/about-fsc/what-is-fsc/fsc-principles (accessed on 3 May 2017). (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6xBXwVgke).

- Breukink, G.; Levin, J.; Mo, K. Profitability and Sustainability in Responsible Forestry: Economic Impacts of FSC Certification on Forest Operators, WWF. 2015. Available online: http://d2ouvy59p0dg6k.cloudfront.net/downloads/profitability_and_sustainability_in_responsible_forestry_main_report_final.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2017).

- Carillion. We Are Making Choices: Carillion’s Environment, Community and Social Report 1999–2000; Carillion plc: Wolverhampton, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- GFTN. GFTN-UK Forest Product Reporting Summary for 2015: Carillion plc. 2016. Available online: https://carillionplc-uploads-shared.s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/1332BJ-carillion-gftn-uk-2015-published-timber-report-original.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2017). (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6xBY8pzrJ).

- Carillion. How We’re Making Tomorrow a Better Place: Carillion Sustainability Report 2016. Wolverhampton: Carillion plc. 2017. Available online: http://sustainability2016.carillionplc.com/assets/files/carillion-sr2016-full.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2017). (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6xBaRFVYP).

- Carillion. Supply Chain Team Survey; Carillion: Wolverhampton, UK, 2017; unpublish. [Google Scholar]

- UK Government. UK Modern Slavery Act. 2015. Available online: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2015/30/contents/enacted (accessed on 3 May 2017)(Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6xBYqVD4m).

- Silverman, B. Modern Slavery: An application of Multiple Systems Estimation, UK Government, London. 2014. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/386841/Modern_Slavery_an_application_of_MSE_revised.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2017)(Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6xBYHOaez).

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Greening the Building Supply Chain. United Nations Environment Programme. In Division of Technology, Industry and Economics; Sustainable Buildings and Climate Initiative: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Allain, J.; Crane, A.; LeBaron, G.; Behbahani, L. Forced Labour’s Business Models and Supply Chains; Joseph Rowntree Foundation & Queens University: Belfast, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gold, S.; Trautrims, A.; Trodd, Z. Modern slavery challenges to supply chain management. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2015, 20, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New, S. Modern slavery and the supply chain: The limits of corporate social responsibility? Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2015, 20, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carillion. Labour Standards Charter. 2017. Available online: https://carillionplc-uploads-shared.s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/0919FQ-cai0209_labour-standards-charter_jan2017-original.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2017). (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6xBYgCHY9).

- Action Sustainability, Supply Chain Sustainability School: Modern Slavery. 2016. Available online: https://www.supplychainschool.co.uk/default/modern-slavery.aspx (accessed on 7 May 2017). (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6xBYQAJ3f).

- Lloyd-Roberts, S. Qatar 2022: Construction Firms Accused Amid Building Boom, BBC Newsnight. 8 December 2014. Available online: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-30295183 (accessed on 9 November 2017). (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6xBamEK3H).

- Basset Hound Rescue Southern California (BHRSC). A Wall of Silence: The Construction Sector’s Response to Migrant Rights in Qatar and UEA; Business and Human Rights Resource Centre: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, R.; Kelly, A. Migrant Workers in Qatar Still at Risk Despite Reforms, Warns Amnesty, The Guardian. 13 December 2016. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/dec/13/migrant-workers-in-qatar-still-at-risk-despite-reforms-warns-amnesty (accessed on 9 November 2017). (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6xBaeDovb).

- Cai, X.; Tsai, C.; Wu, W. Are they neck and neck in the affordable housing policies? A cross case comparison of three metropolitan cities in China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oelze, N. Sustainable supply chain management implementation–Enablers and barriers in the textile industry. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FSC. FSC®: A Tool to Implement the Sustainable Development Goals. 2016. Available online: https://ic.fsc.org/en/web-page-/fsc-contributions-to-achieving-the-sustainable-development-goals (accessed on 6 May 2017). (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6xBaz1uYG).

- Schmidt, C.; Foerstl, K.; Schaltenbrand, B. The supply chain position paradox: Green practices and firm performance. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2017, 53, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualandris, J.; Klassen, R.D.; S Vachon, S.; Kalchschmidt, M. Sustainable evaluation and verification in supply chains: Aligning and leveraging accountability to stakeholders. J. Oper. Manag. 2015, 38, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segall, D.; Labowitz, S. Making Workers Pay: Recruitment of the Migrant Labor Force in the Gulf Construction Industry; NYU Stern Centre for Business and Human Rights: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNSD. Global Indicator Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals and Targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, Global Indicator Framework A RES 71 313 Annex, Statistical Commission Pertaining to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. United Nations, 2017. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/Global%20Indicator%20Framework_A.RES.71.313%20Annex.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2017). (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6xBbEFjMi).

- University of Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (CISL). Towards a Sustainable Economy: The Commercial Imperative for Business to Deliver the UN Sustainable Development Goals; Vrettos, A., Ed.; CISL; University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2017; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, C.R.; Rogers, D.S. A framework of sustainable supply chain management: Moving toward new theory. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2008, 38, 360–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensesn, A.L.; Knudsen, J.S. Sustainable competitiveness in global value chains: How do small Danish firms behave. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2006, 6, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spekman, R.; Kamauff, J.; Myhr, N. An empirical investigation into supply chain management: A perspective on partnerships. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 1998, 34, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.; Fearne, A. Partnerships and alliances in UK supermarket supply networks. In Food Supply Cain Management; Bourlakis, M., Weightman, P., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 136–152. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, S. Supply Chain Specific? Understanding the Patchy Success of Ethical Sourcing Initiatives. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO Forced Labour Convention (No29), Geneva, Switzerland, 1930. Available online: http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@asia/@robangkok/documents/genericdocument/wcms_346435.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2017). (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6xBYYUDum).

| Team | Role | Length of Interview |

|---|---|---|

| Supply Chain | Supplier Accreditation and Monitoring | 1 h |

| Supply Chain | Supplier Accreditation and Management | 1 h |

| Supply Chain | Managing Regional Strategy, supply chain procurement—multiple projects, client liaison | 1 h |

| Supply Chain | Managing Regional Supply Chain Team-multiple projects, client liaison | 1 h |

| Supply Chain | Managing Regional Supply Chain Team-multiple projects, client liaison | 1 h |

| Supply Chain | Managing Procurement—Joint Venture | 1.15 h |

| Supply Chain | Leading team for large public-sector project, delivery, client liaison | 1 h |

| Sustainability | Corporate Sustainability—policy, strategy and reporting | 45 min |

| Sustainability | Business Unit Sustainability Strategy—monitoring, reporting, leading project sustainability | 1 h |

| FSC | Modern Slavery | |

|---|---|---|

| Status | Optional | Mandatory |

| Lead | bottom-up | top-down |

| Time | 20 years of experience/mature process | 2 years since implementation of UK act. Process still developing |

| Corporate Drivers for Action | Initially NGO pressure and consumer concern on product providers 1 | NGO pressure driving legislation |

| Personal Drivers for Supply Chain team | High decision makers with values aligned to FSC social and environmental aims | Meeting legalisation, alignment with general values |

| Network Collaboration | longer term collaboration has allowed development of relationships and trust within network | short development time resulting in collaboration primarily with peers |

| Implementation | FSC policy, Chain of Custody | MS Policy, and Audit |

| Theme | Modern Slavery (Top-Down Goal Setting) | FSC (Bottom-Up Goal Setting) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Defining ‘What is right’ | B | Commitment by Government to a legal ‘solution’ defines the ‘ethical’ position for the supply network. | C | Requires commitment, to buy FSC timber and create market demand, which can be difficult in a business-to-business sector. |

| B | Negotiated’ agreement across the supply chain—engagement with personal and corporate values | |||

| Collaboration | B | In the UK the legal requirement has created a level playing field and engendered collaboration between construction industry organisations/companies. This has resulted in shared costs. | B | Demands collaboration along the supply network. |

| C | Supply network collaborators may have different goals (i.e., improved living conditions, reducing loss of rainforest, minimising cost). | |||

| Relationships | C | It is difficult to get beyond Tiers 1 & 2 especially in global networks; modern slavery most likely to occur in tiers 4, 5 and beyond. | B | Considers social, environmental and economic issues making it attractive for local communities to engage and support. |

| C | Tentative relationships with NGOs | B | Strong supportive engagement of NGOs offering critical assessments and validation. | |

| B | Positive benefits to downstream SMEs engaged in process. | |||

| B | Senior procurement staff are engaged with downstream end suppliers (FSC) | |||

| B | Reduces the likelihood of modern slavery as it can remove exploitative drivers e.g., illegal logging | |||

| Control | C | Modern slavery is driven by issues outside the control of corporate organisations i.e., inequalities, legal protection of vulnerable workers in some countries | B | Operates as a non-governmental process, unrestricted by national borders. |

| Ability to Deliver | C | Demands for ‘no slavery in the supply network’ are strained by time pressured delivery requirements. | C | Documenting Chain of Custody is critical to maintain credibility but increases costs and is complex to manage |

| C | Modern slavery is frequently linked to ‘illegal’ labour and exploitation—policies, charters and audits struggle to reach lower Tiers | |||

| Transparency | C | Reporting by major companies but currently weak driver across rest of supply chain | B | Detailed and transparent reporting |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Russell, E.; Lee, J.; Clift, R. Can the SDGs Provide a Basis for Supply Chain Decisions in the Construction Sector? Sustainability 2018, 10, 629. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030629

Russell E, Lee J, Clift R. Can the SDGs Provide a Basis for Supply Chain Decisions in the Construction Sector? Sustainability. 2018; 10(3):629. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030629

Chicago/Turabian StyleRussell, Erica, Jacquetta Lee, and Roland Clift. 2018. "Can the SDGs Provide a Basis for Supply Chain Decisions in the Construction Sector?" Sustainability 10, no. 3: 629. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030629

APA StyleRussell, E., Lee, J., & Clift, R. (2018). Can the SDGs Provide a Basis for Supply Chain Decisions in the Construction Sector? Sustainability, 10(3), 629. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030629