Exploring the Effect of Time Horizon Perspective on Persuasion: Focusing on Both Biological and Embodied Aging

Abstract

1.Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Socioemotional Selectivity Theory (SST)

2.2. Goal Pursuit

2.3. Embodied Aging

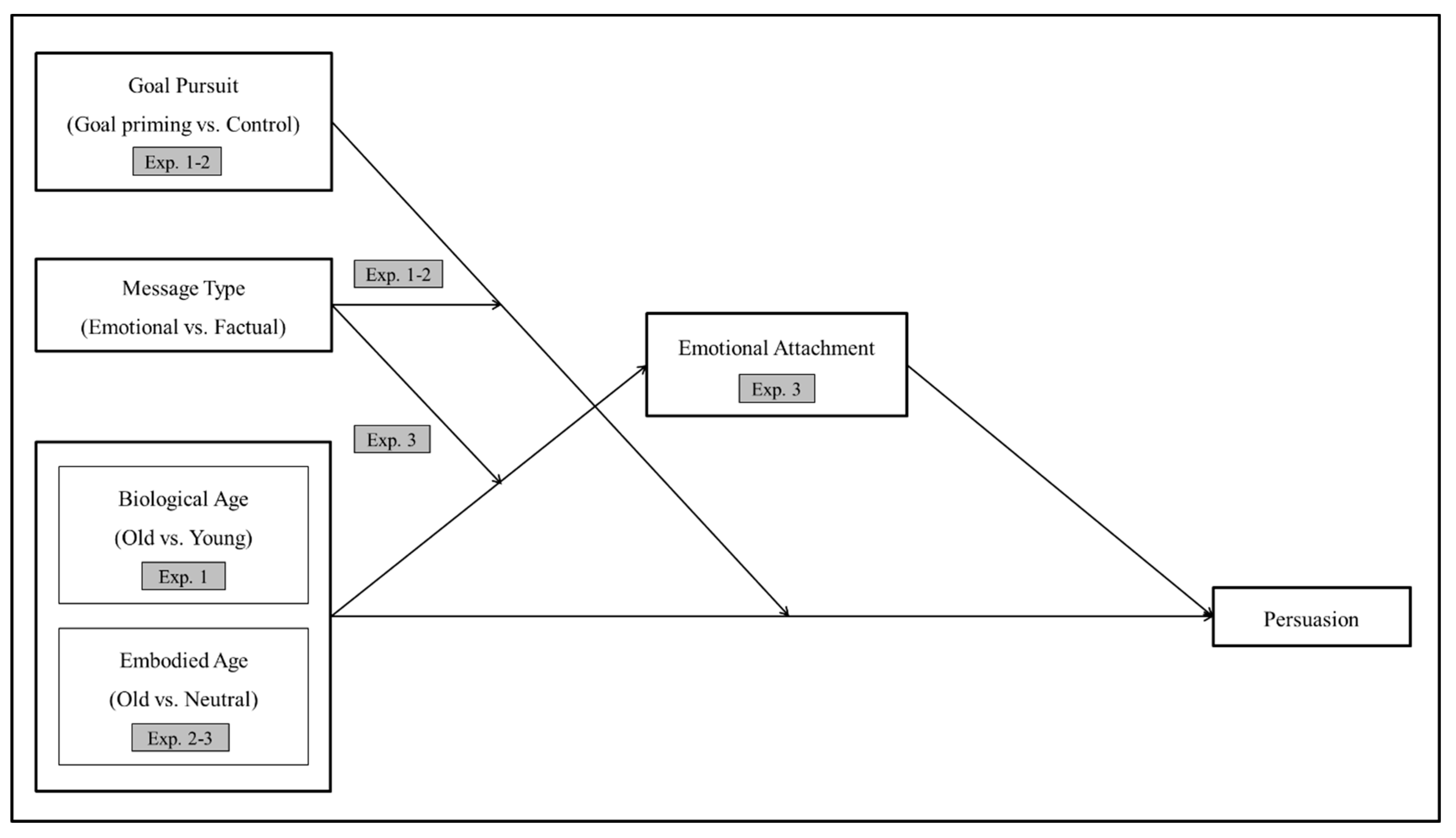

3. Experiment Overview

3.1. Experiment 1

3.1.1. Method

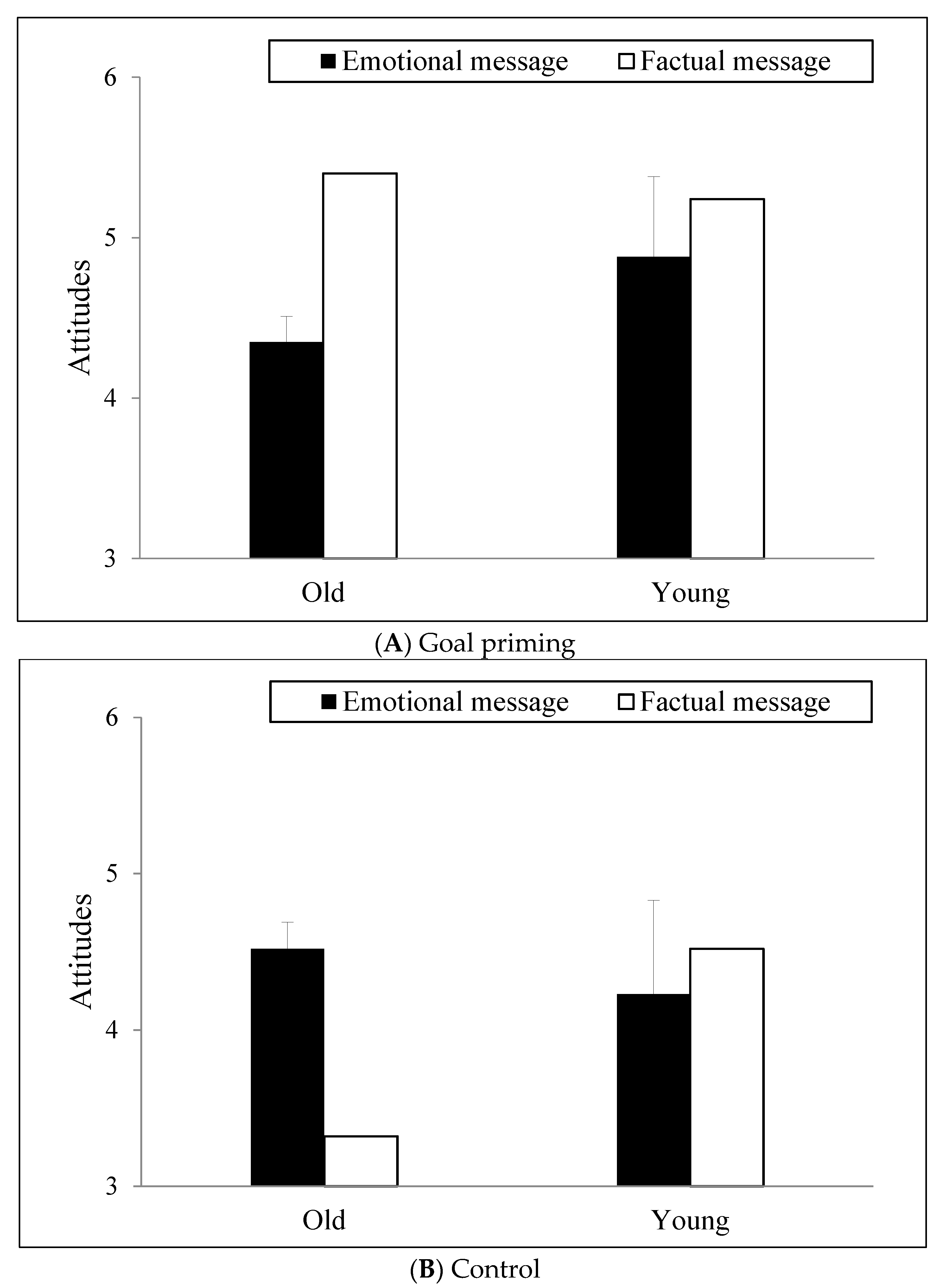

3.1.2. Results

3.1.3. Discussion

3.2. Experiment 2

3.2.1. Method

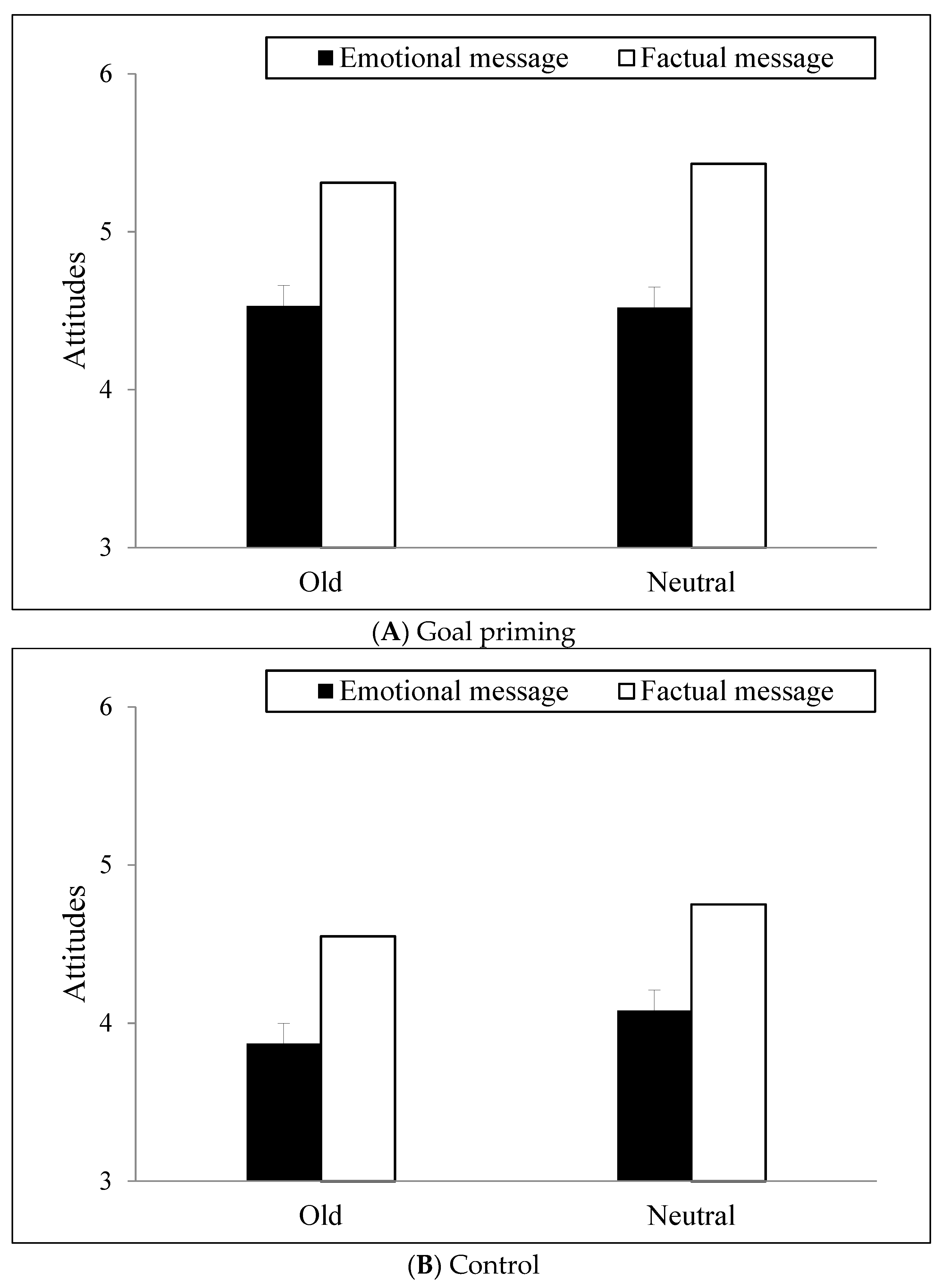

3.2.2. Results

3.2.3. Discussion

3.3. Experiment 3

3.3.1. Method

3.3.2. Results

3.3.3. Discussion

4. General Discussion

4.1. Managerial Implications

4.2. Theoretical Contribution

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cabeza, R. Hemispheric asymmetry reduction in older adults: The HAROLD model. Psychol. Aging 2002, 17, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raz, N. Aging of the brain and its impact on cognitive performance integration of structural and functional findings. In The Handbook of Aging and Cognition, 2nd ed.; Craik, F.I.M., Salthouse, T.A., Eds.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 1–90. [Google Scholar]

- Reuter-Lorenz, P.A.; Lustig, C. Brain aging: Reorganizing discoveries about the aging mind. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2005, 15, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salat, D.H.; Buckner, R.L.; Snyder, A.Z.; Greve, D.N.; Desikan, R.S.R.; Busa, E.; Morris, J.C.; Dale, A.M.; Fischl, B. Thinning of the cerebral cortex in aging. Cereb. Cortex 2004, 14, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carstensen, L.L. Social and emotional patterns in adulthood: Support for socioemotional selectivity theory. Psychol. Aging 1992, 7, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, C.; Laurent, G.; Drolet, A.; Ebert, J.; Gutchess, A.; Lambert-Pandraud, R.; Mullet, E.; Norton, M.I.; Peters, E. Decision making and brand choice by older consumers. Mark. Lett. 2008, 19, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, H.H.; Carstensen, L.L. Sending memorable messages to the old: Age differences in preferences and memory for advertisements. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drolet, A.; Lau-Gesk, L.; Williams, P.; Jeung, H.G. Socioemotional selectivity theory: Implications for consumer research. In The Aging Consumer; Drolet, A., Schwarz, N., Yoon, C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 51–72. [Google Scholar]

- Drolet, A.; Williams, P.; Lau-Gesk, L. Age-related differences in responses to affective vs. rational ads for hedonic vs. utilitarian products. Mark. Lett. 2007, 18, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.; Drolet, A. Age-related differences in responses to emotional advertisements. J. Consum. Res. 2005, 32, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L.L. Evidence for a life-span theory of socioemotional selectivity. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1995, 4, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, S.T.; Mather, M.; Carstensen, L.L. Aging and emotional memory: The forgettable nature of negative images for older adults. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2003, 132, 310–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J.J.; Thompson, R.A. Emotion Regulation: Conceptual Foundations; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen, L.L.; Fung, H.H.; Charles, S.T. Socioemotional selectivity theory and the regulation of emotion in the second half of life. Motiv. Emot. 2003, 27, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biehal, G.; Chakravarti, D. Information-presentation format and learning goals as determinants of consumers’ memory retrieval and choice processes. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 8, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbach, A.; Labroo, A.A. Be better or be merry: How mood affects self-control. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 93, 158–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grouzet, F.M.E.; Kasser, T.; Ahuvia, A.; Dols, J.M.F.; Kim, Y.; Lau, S.; Ryan, R.M.; Saunders, S.; Schmuck, P.; Sheldon, K.M. The structure of goal contents across 15 cultures. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 89, 800–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, M.; Fishbach, A. Dynamics of self-regulation: How (un) accomplished goal actions affect motivation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 94, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huffman, C.; Houston, M.J. Goal-oriented experiences and the development of knowledge. J. Consum. Res. 1993, 20, 190–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L.L.; Isaacowitz, D.M.; Charles, S.T. Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. Am. Psychol. 1999, 54, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J.J. The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1998, 2, 271–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.M.; Gross, J.J. Emotion regulation and memory: The cognitive costs of keeping one’s cool. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 410–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, J.; Wang, J. How time horizon perceptions and relationship deficits affect impulsive consumption. J. Mark. Res. 2013, 50, 590–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinote, A. Power and goal pursuit. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 33, 1076–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberman, N.; Idson, L.C.; Higgins, E.T. Predicting the intensity of losses vs. non-gains and non-losses vs. gains in judging fairness and value: A test of the loss aversion explanation. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 41, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markman, A.B.; Brendl, C.M. The influence of goals on value and choice. Psychol. Learn. Motiv. 2000, 39, 97–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruglanski, A.W.; Webster, D.M. Motivated closing of the mind: “Seizing” and “freezing”. Psychol. Rev. 1996, 103, 263–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Dholakia, U. Goal setting and goal striving in consumer behavior. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargh, J.A. Goal ≠ intent: Goal-directed thought and behavior are often unintentional. Psychol. Inq. 1990, 1, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, J.Y.; Kruglanski, A.W. When opportunity knocks: Bottom-up priming of goals by means and its effects on self-regulation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 1109–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custer, R.; Aarts, H. Positive affect as implicit motivator: On the nonconscious operation of behavioral goals. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 89, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, J.T.; Vancouver, J.B. Goal constructs in psychology: Structure, process, and content. Psychol. Bull. 1996, 120, 338–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Föster, J.; Higgins, E.T. How global versus local perception fits regulatory focus. Psychol. Sci. 2005, 16, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruglanski, A.W.; Shah, J.Y.; Pierro, A.; Mannetti, L. When similarity breeds content: Need for closure and the allure of homogeneous and self-resembling groups. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 648–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblatt, L.M. Towards a transactional theory of reading. J. Lit. Res. 1969, 1, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblatt, L.M. The transactional theory: Against dualisms. Coll. Engl. 1993, 55, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettman, J.R. An Information Processing Theory of Consumer Choice; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Barsalou, L.W. Perceptual symbol systems. Behav. Brain Sci. 1999, 22, 577–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barsalou, L.W. Grounded cognition. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 2008, 59, 617–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, J.I.; Markman, A.B. Embodied cognition as a practical paradigm: Introduction to the topic, the future of embodied cognition. Top. Cogn. Sci. 2012, 4, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niedenthal, P.M.; Barsalou, L.W.; Winkielman, P.; Krauth-Gruber, S.; Ric, F. Embodiment in attitude, social perception, and emotion. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2005, 9, 184–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, J.S.; Billeter, D.M. Consumer behavior in “equilibrium”: How experiencing physical balance increases compromise choice. J. Mark. Res. 2013, 50, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargh, J.A.; Chen, M.; Burrows, L. Automaticity of social behavior: Direct effects of trait construct and stereotype activation on action. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 71, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follenfant, A.; Légal, J.B.; Marie Dit Dinard, F.; Meyer, T. Effect of stereotypes activation on behavior: An application in a sport setting. Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 55, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambon, M. Embodied perception with others’ bodies in mind: Stereotype priming influence on the perception of spatial environment. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 45, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.Y.; Min, D. Embodiment and perspective taking. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Association for Consumer Research, Jacksonville, FL, USA, 7 October 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, M.; MacInnis, D.J.; Park, C.W. The ties that bind: Measuring the strength of consumers’ emotional attachments to brands. J. Consum. Psychol. 2005, 15, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, F.; Solomon, S.; Maxfield, M.; Pyszczynski, T.; Greenberg, J. Fatal attraction: The effects of mortality salience on evaluations of charismatic, task-oriented, and relationship-oriented leaders. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 15, 846–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCoy, S.K.; Major, B. Priming meritocracy and the psychological justification of inequality. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 43, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ahn, A.; Min, D. Exploring the Effect of Time Horizon Perspective on Persuasion: Focusing on Both Biological and Embodied Aging. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4375. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124375

Ahn A, Min D. Exploring the Effect of Time Horizon Perspective on Persuasion: Focusing on Both Biological and Embodied Aging. Sustainability. 2018; 10(12):4375. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124375

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhn, Ahreem, and Dongwon Min. 2018. "Exploring the Effect of Time Horizon Perspective on Persuasion: Focusing on Both Biological and Embodied Aging" Sustainability 10, no. 12: 4375. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124375

APA StyleAhn, A., & Min, D. (2018). Exploring the Effect of Time Horizon Perspective on Persuasion: Focusing on Both Biological and Embodied Aging. Sustainability, 10(12), 4375. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124375