On Protection of Intangible Cultural Heritage in China from the Intellectual Property Rights Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Related Work

1.2.1. Use of the Existing IPR Protection Regime

1.2.2. Creation of a Sui Generis Regime for the Protection of the IPR of ICH

1.3. Research Objectives

1.4. Research Methods

- Comparative Analysis: We carried out both horizontal and vertical comparative analyses of the specific provisions of Chinese and foreign intellectual property laws, and drew upon relevant international theories and court rulings for our research.

- Text Analysis: By analyzing the specific provisions of Chinese and foreign intellectual property laws, we strived to identify the best methods for the protection of ICH.

- Case Analysis: To make this research more reliable, we analyzed ICH-related cases, through which we gained an in-depth understanding of the specific laws applied. We also searched for related court rulings and documents in the databases to draw material in support of our research.

- Historical Analysis: In the context of the evolution of IPR legislation such as the copyright law, we analyzed the rationality of expanding the scope of its protection object, and discussed the possibility of incorporating ICH into the category of IPR protection object.

1.5. Contributions of This Research

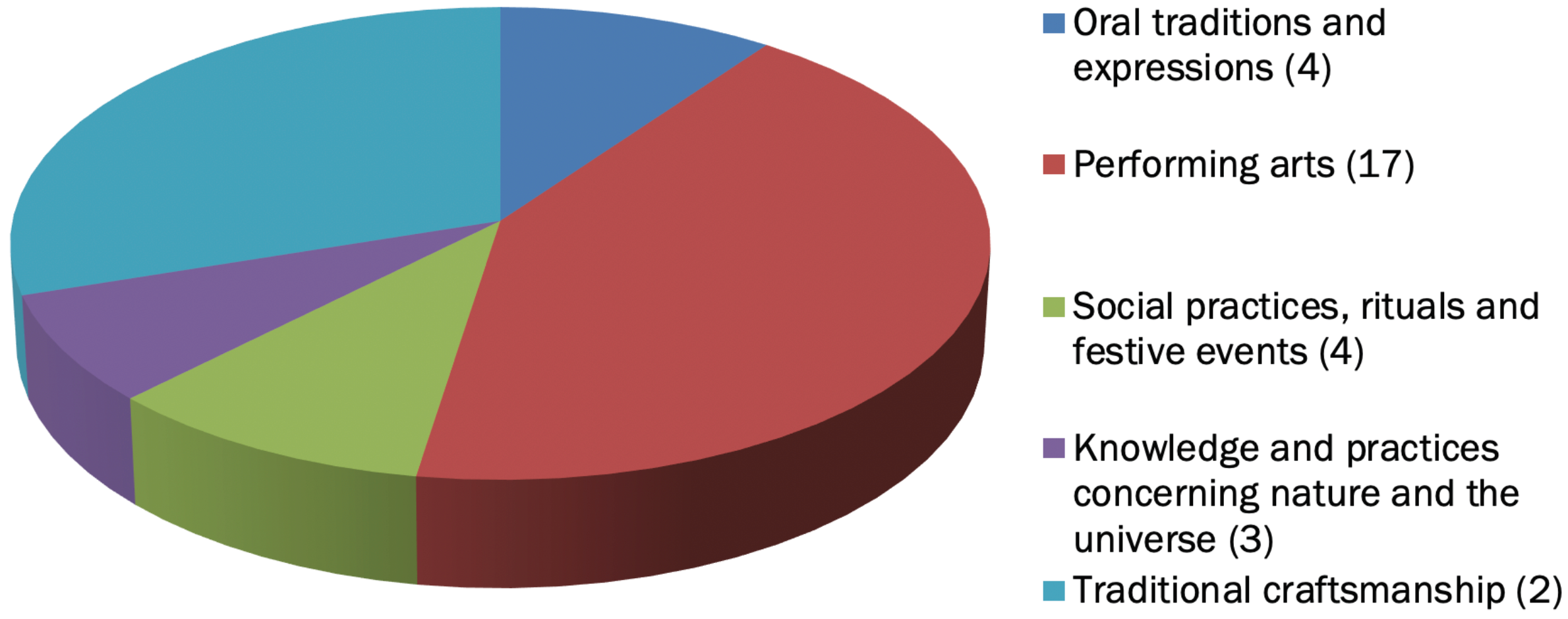

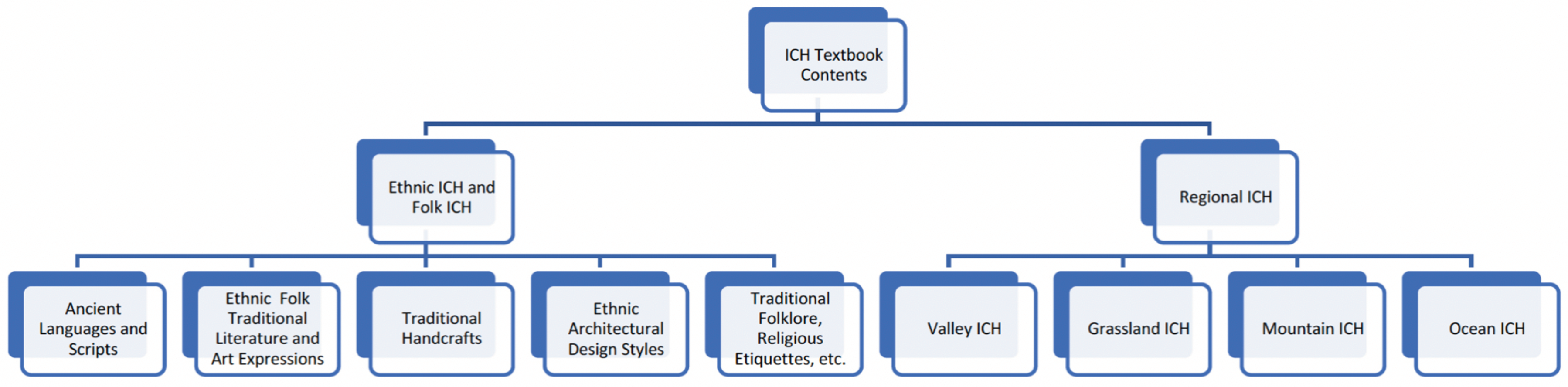

2. Classification of Intangible Cultural Heritage

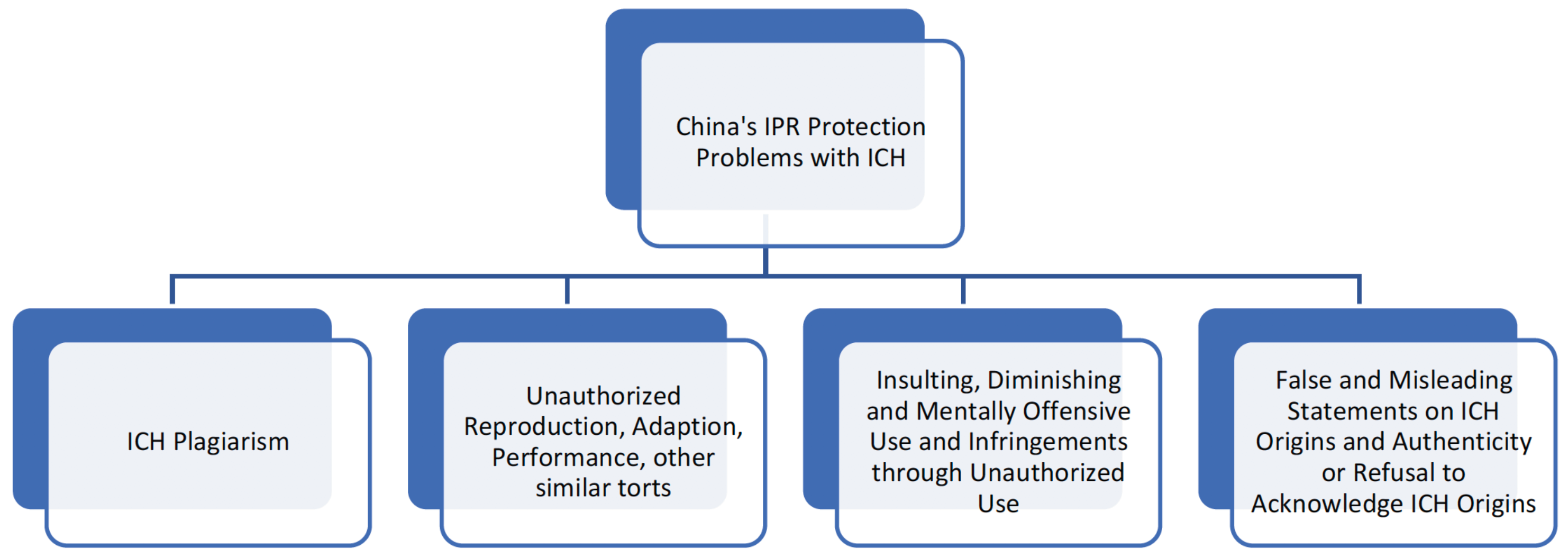

3. Current State of China’s IPR Protection Relating to ICH

3.1. ICH Plagiarism

3.2. Unauthorized Reproduction, Adaption, Performance or Other Similar Torts

3.3. Insulting, Diminishing and Mentally Offensive Use and Infringements through Unauthorized Use

3.4. False and Misleading Statements on ICH Origins and Authenticity or Refusal to Acknowledge ICH Origins

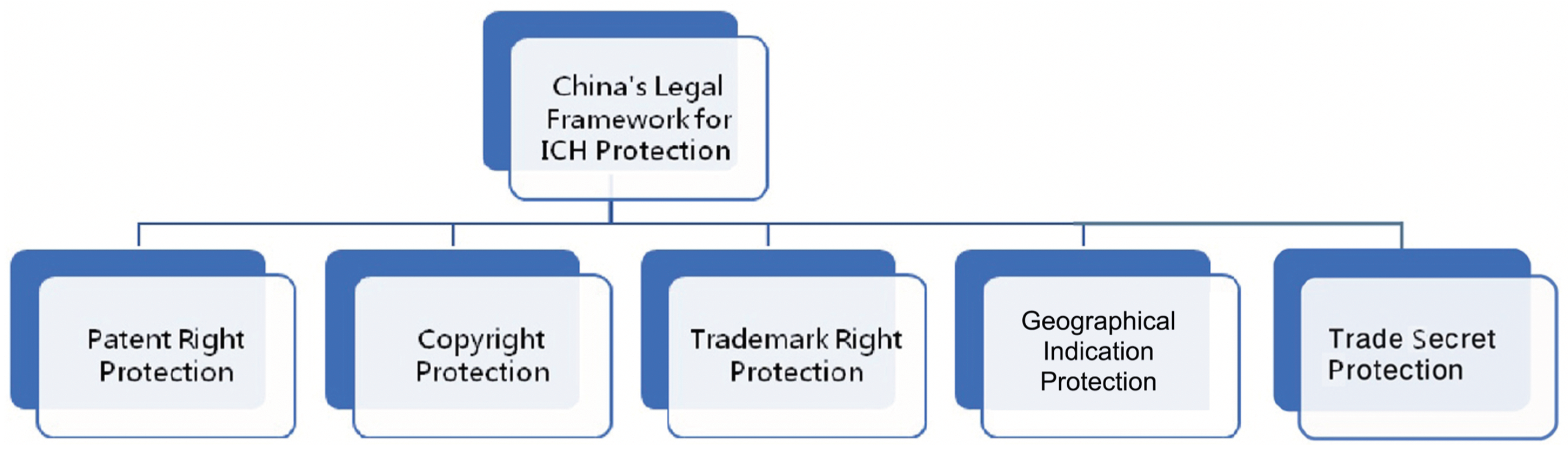

4. Establishment of China’s IPR Protection System for ICH

4.1. China’s Protection for ICH under the Patent Law

4.1.1. Advantages of Protecting ICH under the Patent Law

4.1.2. Deficiencies of Protecting ICH under the Patent Law

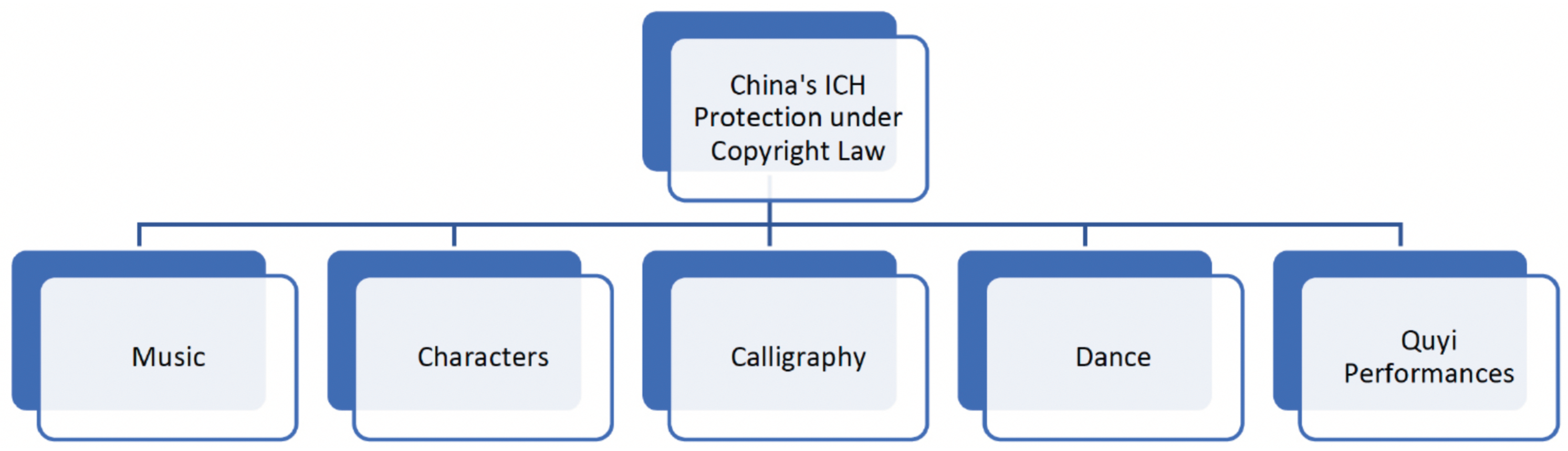

4.2. China’s Copyright Protection for ICH

4.2.1. Advantages of Protecting ICH under the Copyright Law

4.2.2. Deficiencies of Protecting ICH under the Copyright Law

- Object: The object of protection is too narrow. Under China’s Copyright Law, works must be original and complete to be protected, and this disqualifies many ICH items for protection.

- Subject: As ICH is the product of traditional communities and indigenous people through preservation and development over a long period of time, it is difficult to identify the “author” [30].

- Term of Protection: Under China’s Copyright Law, copyrights are protected for the lifetime of the author plus 50 years after his/her death, expiring on 31 December of the 50th year after the author’s death. This means that both the publishing rights and property rights have a term. ICH items are often intergenerational creations with no calculable term for protection.

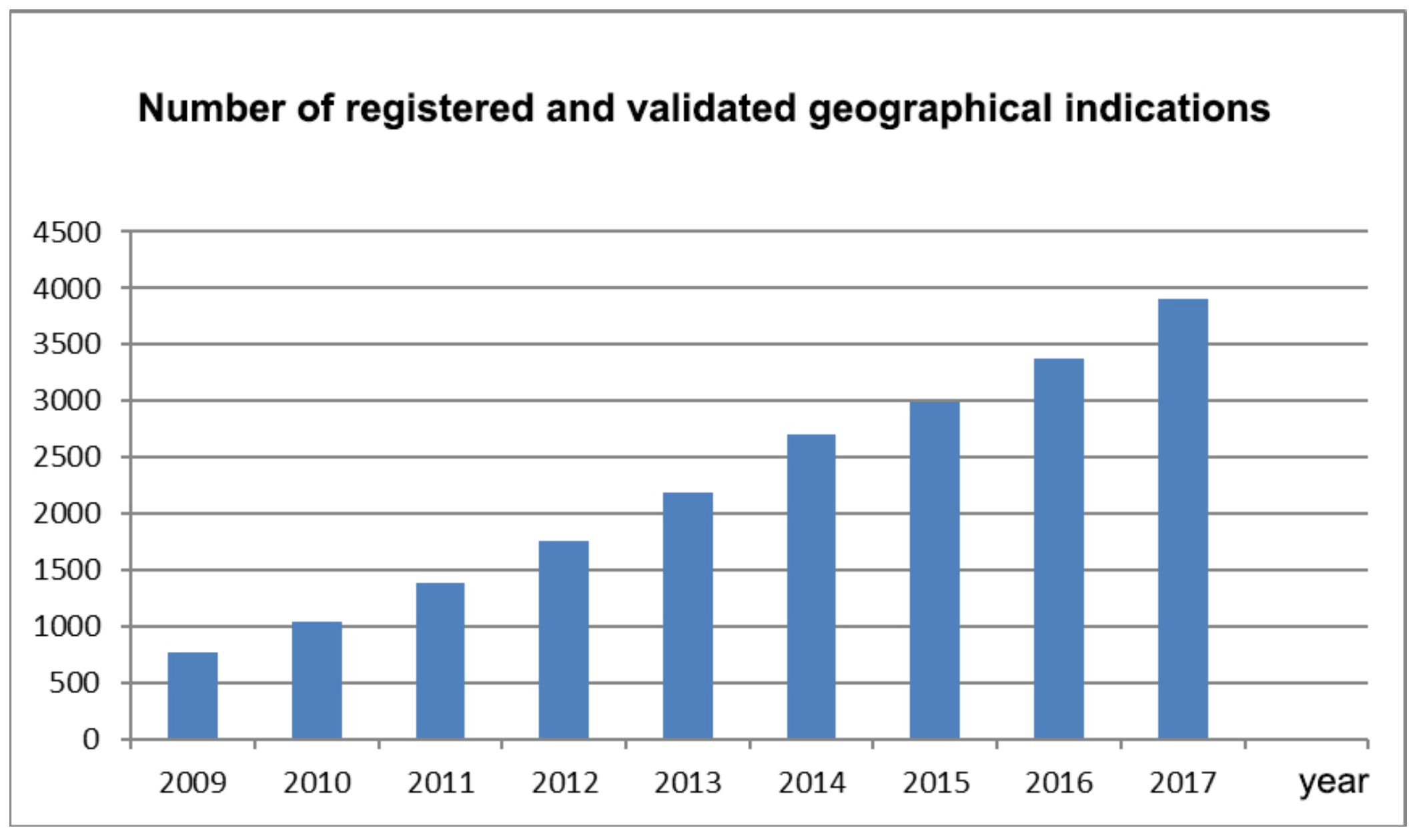

4.3. China’s Protection Systems for ICH Trademark Rights and Geographical Indication Rights

4.3.1. Advantages of Protecting ICH under the Trademark Law

4.3.2. Advantages of Protecting ICH as Geographical Indications

4.3.3. Deficiencies of Protecting ICH as Trademarks and Geographical Indications

4.4. Protection of ICH as Trade Secret

4.4.1. Advantages of Protecting ICH as Trade Secret

4.4.2. Deficiencies of Protecting ICH as Trade Secrets

5. Results via Case Studies

5.1. Case I

5.2. Case II

6. Discussion

- On whether an explicit application for the protection is needed. For copyrights and trade secrets, the protection of ICH is automatic. However, one would have to file a patent application or an application for trademarks and geographical indications to protect the related ICH.

- On the duration of protection. Trade secrets enjoy protection indefinitely. Trademarks and geographical indications can enjoy protection indefinitely as long as the application is renewed properly. Patents enjoy 20 years of protection for inventions and 10 years of protection for utility models and designs. The copyright for an individual’s work enjoys protection until 50 years after the individual has died. The copyright protection for the work of an organization extends to 50 years after the work has been completed.

- On the disclosure policy. Copyrights as well as trademarks and geographical indications are obviously fully disclosed. Contents of the patent must be disclosed and executable. The protection of trade secrets requires sound confidentiality measures.

- On the scope of protection. For copyrights, the protection only applies to expressions, and it cannot prohibit non-plagiarized identicalness. For patents, the protection is limited by the scope of the patent applied for. Trade secrets protection prohibits obtainment of them by illegal means, but it does not apply to independent research and development. Protection for trademarks and geographical indications prevents the use of registered trademarks or geographical indications on identical or similar goods or services because doing so may cause confusion among consumers.

6.1. Recommendations for Improving Copyright Protection for ICH in China

6.2. Recommendations for Improving Trademark and Geographical Indication Protection for ICH in China

6.3. Recommendations for Improving Patent Protection for ICH in China

7. Limitations of the Study

8. Conclusion and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ICH | Intangible Cultural Heritage |

| TRIP | Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| IPR | Intellectual Property Right |

| TCE | Traditional Cultural Expressions |

References

- Vecco, M.; Srakar, A. The unbearable sustainability of cultural heritage: An attempt to create an index of cultural heritage sustainability in conflict and war regions. J. Cult. Herit. 2018, 33, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, F.; Martellozzo, F.; Nolè, G.; Murgante, B. Preserving cultural heritage by supporting landscape planning with quantitative predictions of soil consumption. J. Cult. Herit. 2017, 23, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Dico, G.; Semilia, F.; Milioto, S.; Parisi, F.; Cavallaro, G.; Inguì, G.; Makaremi, M.; Pasbakhsh, P.; Lazzara, G. Microemulsion Encapsulated into Halloysite Nanotubes and their Applications for Cleaning of a Marble Surface. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roveri, M.; Raneri, S.; Bianchi, S.; Gherardi, F.; Castelvetro, V.; Toniolo, L. Electrokinetic Characterization of Natural Stones Coated with Nanocomposites for the Protection of Cultural Heritage. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallaro, G.; Milioto, S.; Parisi, F.; Lazzara, G. Halloysite Nanotubes Loaded with Calcium Hydroxide: Alkaline Fillers for the Deacidification of Waterlogged Archeological Woods. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 27355–27364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavallaro, G.; Lazzara, G.; Milioto, S.; Parisi, F. Halloysite Nanotubes for Cleaning, Consolidation and Protection. Chem. Rec. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, M. UNESCO: Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H. Rethinking the Attributes of Private Rights of Intellectual Property. Soc. Sci. 2005, 2005, 63–64. [Google Scholar]

- Oguamanam, C. Localizing intellectual property in the globalization epoch: The integration of Indigenous knowledge. Indiana J. Glob. Legal Stud. 2004, 11, 135–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodle, K.; Brimble, M.; Weaven, S.; Frazer, L.; Blue, L. Critical success factors in managing sustainable indigenous businesses in Australia. Pac. Account. Rev. 2018, 30, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhavan, H. Below the radar innovations and emerging property right approaches in Tibetan medicine. J. World Intellect. Prop. 2017, 20, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ubertazzi, B. EU Geographical Indications and Intangible Cultural Heritage. IIC-Int. Rev. Intellect. Prop. Compet. Law 2017, 48, 562–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodionova, O. The specifics of the russian intellectual-legal protection of cultural works (for example finno-ugric peoples. Mord. Univ. Bull. 2015, 25, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwabueze, C.J. The role of intellectual property in safeguarding intangible cultural heritage in museums. Int. J. Intang. Herit. 2013, 8, 181–190. [Google Scholar]

- Torsen, M. Intellectual property and traditional cultural expressions: A synopsis of current issues. Intercult. Hum. Rights Law Rev. 2008, 3, 199. [Google Scholar]

- May, C. The world intellectual property organization. New Political Econ. 2006, 11, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Horton, C.M. Protection Biodiversity and Cultural Diversity under Intellectual Property Law: Toward a New International System. J. Environ. Law Litig. 1995, 10, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, A. Integrated IPR Protection for Intangible Cultural Heritage. Electron. Intellect. Prop. 2007, 2007, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, A. Fundamental Though on the Legal Protection of Intangible Cultural Heritage. Jiangsi Soc. Sci. 2006, 2006, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z. Legal Protection of Intangible Cultural Heritage Thought Centered on IPR. Intellect. Prop. Rights 2005, 2005, 54–57. [Google Scholar]

- OseiTutu, J.J. A sui generis regime for traditional knowledge: The cultural divide in intellectual property law. Marquette Intellect. Prop. Law Rev. 2011, 15, 147. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, Y. Discussion on Legal Protection of Intangible Cultural Heritage. 2008. Available online: http://www.iolaw.org.cn/showNews.asp?id (accessed on 18 December 2008).

- Li, S. Legal definition of Intangible Cultural Heritage and Protection of Intellectual Property. Jiangxi Soc. Sci. 2006, 2006, 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K.; Cheng, L. Legal Definition of Folk Literature and Art. J. Beijing Univ. Ind. Commer. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2005, 2005, 92. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T. Empirical Study of Local Legislation for Intangible Cultural Heritage. Huxiang Forum 2018, 135–145. Available online: http://mall.cnki.net/onlineview/MagaView.aspx?fn=hxlt201805*1* (accessed on 10 November 2018).

- Chen, W. Exploring the Feasibility of Traditional Knowledge Being Protected under the Patent System. Law Rev. Chengchi Univ. (Taiwan) 1993, 78, 163–164. [Google Scholar]

- Kartomi, M.J. Ethnomusicological Education for a Humane Society: Ethical Issues in the Post-Colonial, Post-Apartheid Era. Afr. Music 1999, 7, 166–174. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, S. Indigenous music and the law: An analysis of national and international legislation. Yearbook Tradit. Music 1996, 28, 57–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadirgamar, L. Interfaces Between Intellectual Property, Traditional Knowledge, Genetic Resources and Folklore: Problem and Solutions. J. Malays. Comp. Law 2013, 29. Available online: http://www.commonlii.org/my/journals/JMCL/2002/5.html#Heading178 (accessed on 10 November 2018).

- Lin, Q. Theory & Practice of Intangible Cultural Heritage Protection; Posts & Telecom Press: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; Duan, T. Dilemma in the Process of Asserting the “Rights” of Geographical Indication Trademarks. Chin. Trademarks 2012, 2012, 39–41. [Google Scholar]

- Pooley, J.; Westman, D.P. Trade Secrets; Law Journal Seminars-Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kremers, N. Speaking with a Forked Tongue in the Global Debate on Traditional Knowledge and Genetic Resources: Is US Intellectual Property Law and Policy Really Aimed at Meaningful Protection for Native American Cultures. Fordham Intell. Prop. Media Entertain. Law J. 2004, 15, 1–147. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, Q.; Lian, Z. On Protection of Intangible Cultural Heritage in China from the Intellectual Property Rights Perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4369. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124369

Lin Q, Lian Z. On Protection of Intangible Cultural Heritage in China from the Intellectual Property Rights Perspective. Sustainability. 2018; 10(12):4369. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124369

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Qing, and Zheng Lian. 2018. "On Protection of Intangible Cultural Heritage in China from the Intellectual Property Rights Perspective" Sustainability 10, no. 12: 4369. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124369

APA StyleLin, Q., & Lian, Z. (2018). On Protection of Intangible Cultural Heritage in China from the Intellectual Property Rights Perspective. Sustainability, 10(12), 4369. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124369