Promoting the Sustainability of Organizations: Contribution of Transformational Leadership to Job Engagement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Task Significance as Mediator

2.2. POS as Mediator

2.3. CSE as Mediator

3. Method

3.1. Sample

3.2. Measures

3.3. Analytical Methods

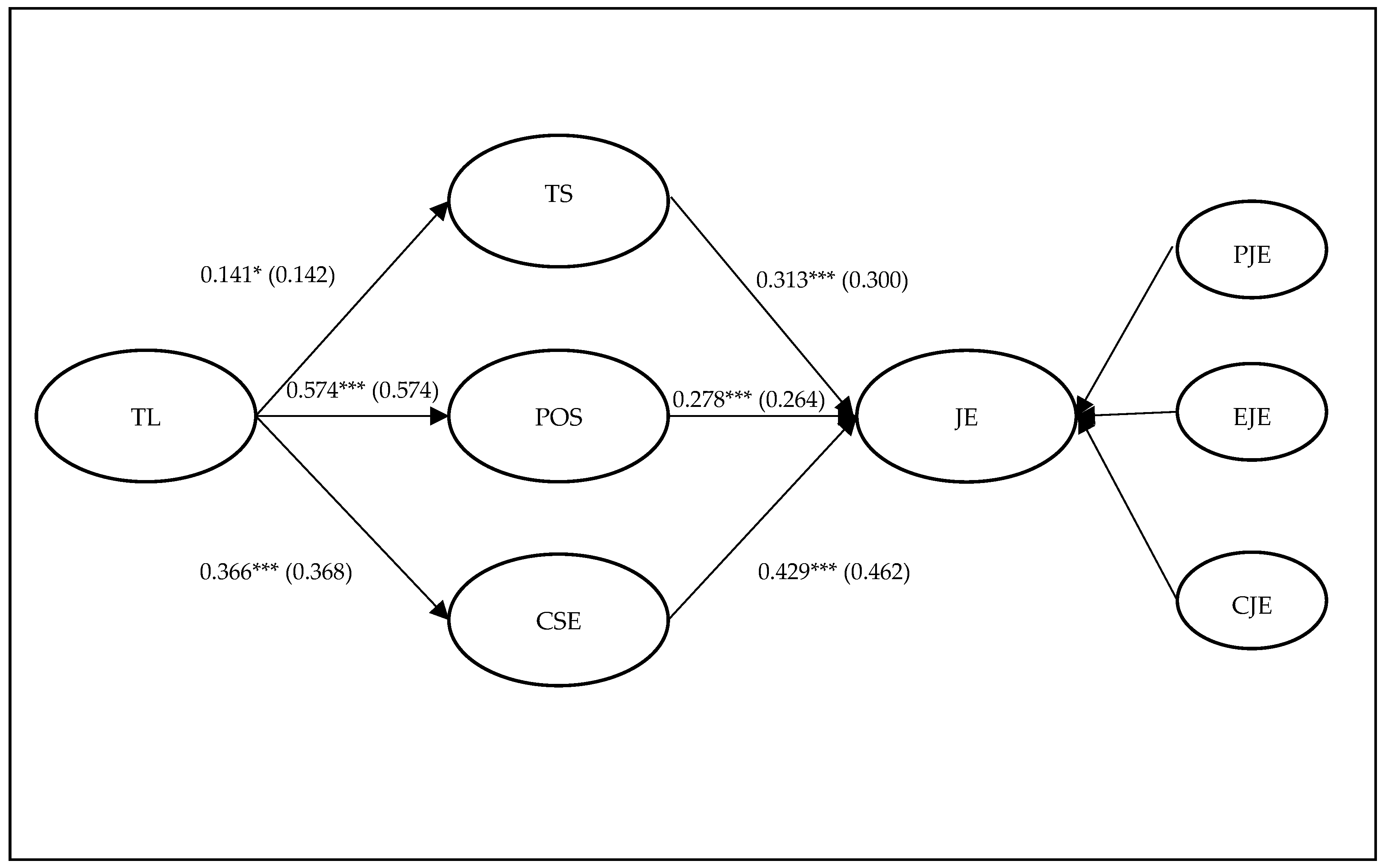

4. Results

5. Discussion and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Di Fabio, A. The psychology of sustainability and sustainable development for well-being in organizations. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Fabio, A. Positive healthy organizations: Promoting well-being, meaningfulness, and sustainability in organizations. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wegge, J.; Shemla, M.; Haslam, S.A. Leader behavior as a determinant of health at work: Specification and evidence of five key pathways. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 28, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, K.A.; Turner, N.; Barling, J.; Kelloway, E.K.; McKee, M.C. Transformational leadership and psychological well-being. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelloway, E.K.; Turner, N.; Barling, J.; Loughlin, C. Transformational leadership and employee psychological well-being: The mediating role of employee trust in leadership. Work Stress 2012, 26, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.; Yarker, J.; Randall, R.; Munir, F. The mediating effects of team and self-efficacy on the relationship between transformational leadership, and job satisfaction and psychological well-being in healthcare professionals: A cross-sectional questionnaire survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009, 46, 1236–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, K.A. Transformational leadership and employee psychological well-being: A review and directions for future research. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, K.; Nielsen, M.B.; Ogbonnaya, C.; Känsälä, M.; Saari, E.; Isaksson, K. Workplace resources to improve both employee well-being and performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Work Stress 2017, 31, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, B.L.; Lepine, J.A.; Crawford, E.R. Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W.; Rhenen, W.V. Workaholism, burnout and engagement: One of a kind or three different kinds of employee well-being? Appl. Psychol. 2008, 57, 173–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkikangas, A.; Feldt, T.; Kinnunen, U.; Mauno, S. Does Personality Matter? A Review of Individual Differences in Occupational Well-Being. In Advances in Positive Organizational Psychology; Bakker, A.B., Ed.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2013; pp. 107–143. ISBN 978-1780520001. [Google Scholar]

- Shimazu, A.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Kamiyama, K.; Kawakami, N. Workaholism vs. work engagement: The two different predictors of future well-being and performance. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2015, 22, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caesens, G.; Stinglhamber, F.; Ohana, M. Perceived organizational support and well-being: A weekly study. J. Manag. Psychol. 2016, 31, 1214–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Schaufeli, W.B. Do burnout and work engagement predict depressive symptoms and life satisfaction? A three-wave seven-year prospective study. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 141, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, C.; Madden, A.; Alfes, K.; Fletcher, L. The meaning, antecedents and outcomes of employee engagement: A narrative synthesis. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2017, 19, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Park, J. Examining structural relationships between work engagement, organizational procedural justice, knowledge sharing, and innovative work behavior for sustainable organizations. Sustainability 2017, 9, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.J.; Zhang, X.I.; Vogel, D. Exploring the underlying processes between conflict and knowledge sharing: A work-engagement perspective. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 41, 1005–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrick, M.R.; Thurgood, G.R.; Smith, T.A.; Courtright, S.H. Collective organizational engagement: Linking motivational antecedents, strategic implementation, and firm performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, S.L.; Bakker, A.B.; Gruman, J.A.; Macey, W.H.; Saks, A.M. Employee engagement, human resource management practices and competitive advantage. J. Organ. Eff. 2015, 2, 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruman, J.A.; Saks, A.M. Performance management and employee engagement. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2011, 21, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Khan, G.; Wood, J.; Mahmood, M. Employee engagement for sustainable organizations: Keyword analysis using social network analysis and burst detection approach. Sustainability 2016, 8, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, S.; Walumbwa, F.O.; Zhou, Q.; Hartnell, C.A. Transformational leadership, innovative behavior, and task performance: Test of mediation and moderation processes. Hum. Perform. 2012, 25, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, H.T.M.; Zeng, Y.; Higgs, M. The role of person-job fit in the relationship between transformational leadership and job engagement. J. Manag. Psychol. 2017, 32, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.H.; Kolb, J.A.; Lee, U.H.; Kim, H.K. Role of transformational leadership in effective organizational knowledge creation practices: Mediating effects of employees’ work engagement. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2012, 23, 65–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin Ghadi, M.; Fernando, M.; Caputi, P. Transformational leadership and work engagement: The mediating effect of meaning in work. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 2013, 34, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopperud, K.H.; Martinsen, Ø.; Humborstad, S.I.W. Engaging leaders in the eyes of the beholder: On the relationship between transformational leadership, work engagement, service climate, and Self–Other agreement. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2014, 21, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breevaart, K.; Bakker, A.; Hetland, J.; Demerouti, E.; Olsen, O.K.; Espevik, R. Daily transactional and transformational leadership and daily employee engagement. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2014, 87, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Xanthopoulou, D. Do transformational leaders enhance their followers’ daily work engagement? Leadersh. Q. 2011, 22, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoch, J.E.; Bommer, W.H.; Dulebohn, J.H.; Wu, D. Do ethical, authentic, and servant leadership explain variance above and beyond transformational leadership? A meta-analysis. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 501–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carasco-Saul, M.; Kim, W.; Kim, T. Leadership and employee engagement: Proposing research agendas through a review of literature. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2015, 14, 38–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, E.R.; Rich, B.L.; Buckman, B.; Bergeron, J. The antecedents and drivers of employee engagement. In Employee Engagement in Theory and Practice; Truss, C., Delbridge, R., Alfes, K., Shantz, A., Soane, E., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 57–81. ISBN 9780415657426. [Google Scholar]

- Saks, A.M.; Gruman, J.A. What do we really know about employee engagement? Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2014, 25, 155–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, R.F.; Colquitt, J.A. Transformational leadership and job behaviors: The mediating role of core job characteristics. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtessis, J.N.; Eisenberger, R.; Ford, M.T.; Buffardi, L.C.; Stewart, K.A.; Adis, C.S. Perceived organizational support: A meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support theory. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1854–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamir, B.; House, R.J.; Arthur, M.B. The motivational effects of charismatic leadership: A self-concept based theory. Organ. Sci. 1993, 4, 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgeson, F.P.; Humphrey, S.E. The work design questionnaire (WDQ): Developing and validating a comprehensive measure for assessing job design and the nature of work. J. Appl. Pychol. 2006, 91, 1321–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgeson, F.P.; Campion, M.A. Work design. In Handbook of Psychology: Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Borman, W.C., Ilgen, D.R., Klimoski, R.J., Eds.; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 423–452. ISBN 9780471666745. [Google Scholar]

- Allan, B.A. Task significance and meaningful work: A longitudinal study. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 102, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M. The significance of task significance: Job performance effects, relational mechanisms, and boundary conditions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goštautaitė, B.; Bučiūnienė, I. Work engagement during life-span: The role of interaction outside the organization and task significance. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 89, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shantz, A.; Alfes, K.; Truss, C.; Soane, E. The role of employee engagement in the relationship between job design and task performance, citizenship and deviant behaviours. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 2608–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvanova, R.K.; Bono, J.E.; Dzieweczynski, J. Transformational leadership, job characteristics, and organizational citizenship performance. Hum. Perform. 2006, 19, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ma, L.; Zhang, M. Transformational leadership and agency workers’ organizational commitment: The mediating effect of organizational justice and job characteristics. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2014, 42, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, M.L.; Fainshmidt, S.; Klinger, R.L.; Pezeshkan, A.; Vracheva, V. Psychological safety: A Meta-Analytic review and extension. Pers. Psychol. 2017, 70, 113–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Stinglhamber, F. Perceived Organizational Support: Fostering Enthusiastic and Productive Employees; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; ISBN 9781433809330. [Google Scholar]

- Brunetto, Y.; Shacklock, K.; Teo, S.; Farr-Wharton, R. The impact of management on the engagement and well-being of high emotional labour employees. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 2345–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Wayne, S.J.; Liden, R.C. Job engagement, perceived organizational support, high-performance human resource practices, and cultural value orientations: A cross-level investigation. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 823–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Erez, A.; Bono, J.E.; Thoresen, C.J. The core self-evaluations scale: Development of a measure. Pers. Psychol. 2003, 56, 303–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Knippenberg, D.; van Knippenberg, B.; De Cremer, D.; Hogg, M.A. Leadership, self, and identity: A review and research agenda. Leadersh. Q. 2004, 15, 825–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Wu, Y.J. How humble leadership fosters employee innovation behavior: A two-way perspective on the leader-employee interaction. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 2018, 39, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messersmith, J.G.; Guthrie, J.P. High performance work systems in emergent organizations: Implications for firm performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010, 49, 241–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Comission. Annual Report on European SMEs 2013–2014—A Partial and Fragile Recovery—EUbusiness; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Desmarchelier, B.; Djellal, F.; Gallouj, F. Knowledge intensive business services and long term growth. Struct. Chang. Econ. Dyn. 2013, 25, 188–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vence-Deza, X.; González-López, M. Regional concentration of the knowledge-based economy in the EU: Towards a renewed oligocentric model? Eur. Plan. Stud. 2008, 16, 557–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, D.R.; Gilson, R.L.; Harter, L.M. The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2004, 77, 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M. Relational job design and the motivation to make a prosocial difference. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 393–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, M.S.; Garza, A.S.; Slaughter, J.E. Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 89–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleavenger, D.J.; Munyon, T.P. It’s how you frame it: Transformational leadership and the meaning of work. Bus. Horiz. 2013, 56, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salancik, G.R.; Pfeffer, J. A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Adm. Sci. Q. 1978, 23, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bass, B.M. Leadership and Performance Beyond Expectations, 1st ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985; p. 256. ISBN 0029018102. [Google Scholar]

- Gözükara, İ.; Şimşek, O.F. Linking transformational leadership to work engagement and the mediator effect of job autonomy: A study in a turkish private non-profit university. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 195, 963–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 350–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Fasolo, P.; Davis-LaMastro, V. Perceived organizational support and employee diligence, commitment, and innovation. J. Appl. Psychol. 1990, 75, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W.A. The essence of engagement: Lessons from the field. In Handbook of Employee Engagement.Perspectives, Issues, Research, and Practice; Albrecht, S.L., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc.: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 20–30. ISBN 9781849809504. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, P. Power and Exchange in Social Life; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1964; p. 352. ISBN 9780471080305. [Google Scholar]

- Saks, A.M. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. J. Manag. Psychol. 2006, 21, 600–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Stinglhamer, F.; Vandenberghe, C.; Sucharski, I.L.; Rhoades, L. Perceived supervisor support: Contributions to perceived organizational support and employee retention. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carless, S.A.; Wearing, A.J.; Mann, L. A short measure of transformational leadership. J. Bus. Psychol. 2000, 14, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Hurst, C. Capitalizing on one’s advantages: Role of core self-evaluations. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1212–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.; Ferris, D.L.; Johnson, R.E.; Rosen, C.C.; Tan, J.A. Core self-evaluations: A review and evaluation of the literature. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 81–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, D.L.; Johnson, R.E.; Rosen, C.C.; Djurdjevic, E.; Chang, C.D.; Tan, J.A. When is success not satisfying? integrating regulatory focus and approach/avoidance motivation theories to explain the relation between core self-evaluation and job satisfaction. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aryee, S.; Walumbwa, F.O.; Mondejar, R.; Chu, C.W.L. Core self-evaluations and employee voice behavior: Test of a dual-motivational pathway. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 946–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.; Hsu, C.; Hung, K. Core self-evaluation and workplace creativity. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1405–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Demir, E. Linking core self-evaluations and work engagement to work-family facilitation: A study in the hotel industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 26, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Ok, C. Drivers of work engagement: An examination of core self-evaluations and psychological climate among hotel employees. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 44, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cremer, D.A.; van Knippenberg, B.M.; van Knippenberg, D.; Mullenders, D.; Stinglhamber, F. Rewarding leadership and fair procedures as determinants of self-esteem. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kark, R.; Shamir, B.; Chen, G. The two faces of transformational leadership: Empowerment and dependency. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, H.; Chuang, A. Transforming service employees and climate: A multilevel, multisource examination of transformational leadership in building long-term service relationships. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1006–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salanova, M.; Lorente, L.; Chambel, M.J.; Martínez, I.M. Linking transformational leadership to nurses’ extra-role performance: The mediating role of self-efficacy and work engagement. J. Adv. Nurs. 2011, 67, 2256–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2007, 14, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Nejadi, S. Do core self-evaluations mediate the effect of coworker support on work engagement? A study of hotel employees in iran. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2010, 17, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Borteyrou, X. Core self-evaluations as a mediator of the relationship between person–environment fit and job satisfaction among laboratory technicians. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2016, 99, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, Z.; Ling, Y.; Cai, T. Core self-evaluations and coping styles as mediators between social support and well-being. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2016, 88, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology: Methodology; Triandis, H.C., Berry, J.W., Eds.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; pp. 389–444. ISBN 9780205064984. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, L. How can personal development lead to increased engagement? The roles of meaningfulness and perceived line manager relations. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T.D.; Cunningham, W.A.; Shahar, G.; Widaman, K.F. To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Struct. Equ. Model. 2002, 9, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988; p. 567. ISBN 9780805802832. [Google Scholar]

- Law, K.S.; Wong, C.; Mobley, W.M. Toward A taxonomy of multidimensional constructs. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 741–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2010; p. 816. ISBN 9780138132631. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Shin, Y.; Baek, S. Task characteristics and work engagement: Exploring effects of role ambiguity and ICT presenteeism. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, J.B.; Schneider, T.R. The effects of leadership style on stress outcomes. Leadersh. Q. 2009, 20, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messersmith, J.G.; Wales, W.J. Entrepreneurial orientation and performance in young firms: The role of human resource management. Int. Small Bus. J. 2013, 31, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegman, L.A.; Hoffman, B.J.; Carter, N.T.; Twenge, J.M.; Guenole, N. Placing job characteristics in context: Cross-temporal meta-analysis of changes in job characteristics since 1975. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 352–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, A.; Hatak, I. A meta-analysis of different HR-enhancing practices and performance of small and medium sized firms. J. Bus. Ventur. 2016, 31, 485–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.; Barling, J.; Zacharatos, A. Positive psychology at work. In Handbook of Positive Psychology; Snyder, C.R., Lopez, S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 715–728. ISBN 9780195135336. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources. A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halbesleben, J.R.B.; Neveu, J.; Paustian-Underdahl, S.C.; Westman, M. Getting to the “COR”. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1334–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakis, J.; Fenley, M.; Liechti, S. Can charisma be taught? Tests of two interventions. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2011, 10, 374–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barling, J.; Weber, T.; Kelloway, E.K. Effects of transformational leadership training on attitudinal and financial outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 827–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E. Method variance in organizational research: Truth or urban legend? Organ. Res. Methods 2006, 9, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Kwan, H.K.; Zhang, X.; Wu, L. High core self-evaluators maintain creativity: A motivational model of abusive supervision. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1151–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | - | - | ||||||||

| 2. Age | 32.09 | 6.18 | −0.09 | |||||||

| 3. Tenure | 3.17 | 2.52 | −0.18 * | 0.37 *** | ||||||

| 4. Transformational leadership | 5.25 | 1.43 | −0.06 | −0.20 *** | −0.16 ** | (0.96) | ||||

| 5. Task significance | 4.71 | 1.30 | −0.00 | 0.10 | −0.02 | 0.14 * | (0.81) | |||

| 6. Perceived organizational support | 4.73 | 1.46 | 0.04 | −0.02 | −0.19 *** | 0.57 *** | 0.28 *** | (0.96) | ||

| 7. Core-self evaluations | 5.30 | 0.82 | −0.03 | −0.13 * | 0.00 | 0.37 *** | 0.32 *** | 0.25 *** | (0.82) | |

| 8. Job engagement | 5.77 | 0.82 | 0.11 | 0.05 | −0.08 | 0.33 *** | 0.49 *** | 0.44 *** | 0.56 *** | (0.93) |

| Models | χ2 | df | CFI | IFI | RMSEA | CI 90% RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-factor structure | 842.983 | 52 | 0.764 | 0.765 | 0.218 | 0.206–0.231 |

| Three-factor structure | 119.601 | 49 | 0.979 | 0.979 | 0.067 | 0.052–0.083 |

| Second-order structure | 119.601 | 49 | 0.979 | 0.979 | 0.067 | 0.052–0.083 |

| TL | TS | POS | CSE | JE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TL | CR = 0.964 | ||||

| AVE = 0.792 | |||||

| TS | SC = 0.019 | CR = 0.818 | |||

| (0.008; 0.266) | AVE = 0.600 | ||||

| POS | SC = 0.328 | SC = 0.080 | CR = 0.959 | ||

| (0.467; 0.679) | (0.157; 0.407) | AVE = 0.797 | |||

| CSE | SC = 0.134 | SC = 0.100 | SC = 0.063 | CR = 0.824 | |

| (0.244; 0.488) | (0.176; 0.458) | (0.123; 0.377) | AVE = 0.610 | ||

| JE | SC = 0.111 | SC = 0.236 | SC = 0.194 | SC =0.316 | CR = 0.855 |

| (0.213; 0.453) | (0.363; 0.609) | (0.333; 0.549) | (0.446; 0.678) | AVE = 0.664 |

| Models | χ2 | df | CFI | IFI | RMSEA | CI 90% RMSEA | Δχ2 | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partial mediation | 1081.833 | 424 | 0.931 | 0.932 | 0.070 | 0.065–0.075 | |||

| Hypothesized model (HM): total mediation | 1081.935 | 425 | 0.931 | 0.932 | 0.070 | 0.064–0.075 | 0.102 | 1 | ns |

| M1 | 1240.245 | 427 | 0.915 | 0.915 | 0.077 | 0.072–0.082 | 158.412 | 3 | <0.001 |

| M2 | 1086.872 | 425 | 0.931 | 0.931 | 0.070 | 0.065–0.075 | 5.039 | 1 | <0.05 |

| M3 | 1199.399 | 425 | 0.919 | 0.919 | 0.076 | 0.071–0.081 | 117.566 | 1 | <0.001 |

| M4 | 1118.409 | 425 | 0.928 | 0.928 | 0.072 | 0.066–0.077 | 36.576 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Indirect Effects TL → VM → JE | Estimate | 95% CI (Lower) | 95% CI (Upper) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: TL → TS → JE | 0.029 | 0.004 | 0.066 | 0.026 |

| H2: TL → POS → JE | 0.106 | 0.059 | 0.170 | 0.001 |

| H3: TL → CSE → JE | 0.104 | 0.059 | 0.162 | 0.001 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vila-Vázquez, G.; Castro-Casal, C.; Álvarez-Pérez, D.; Del Río-Araújo, L. Promoting the Sustainability of Organizations: Contribution of Transformational Leadership to Job Engagement. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4109. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114109

Vila-Vázquez G, Castro-Casal C, Álvarez-Pérez D, Del Río-Araújo L. Promoting the Sustainability of Organizations: Contribution of Transformational Leadership to Job Engagement. Sustainability. 2018; 10(11):4109. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114109

Chicago/Turabian StyleVila-Vázquez, Guadalupe, Carmen Castro-Casal, Dolores Álvarez-Pérez, and Luisa Del Río-Araújo. 2018. "Promoting the Sustainability of Organizations: Contribution of Transformational Leadership to Job Engagement" Sustainability 10, no. 11: 4109. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114109

APA StyleVila-Vázquez, G., Castro-Casal, C., Álvarez-Pérez, D., & Del Río-Araújo, L. (2018). Promoting the Sustainability of Organizations: Contribution of Transformational Leadership to Job Engagement. Sustainability, 10(11), 4109. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114109