3.1. Village and Population Characteristics

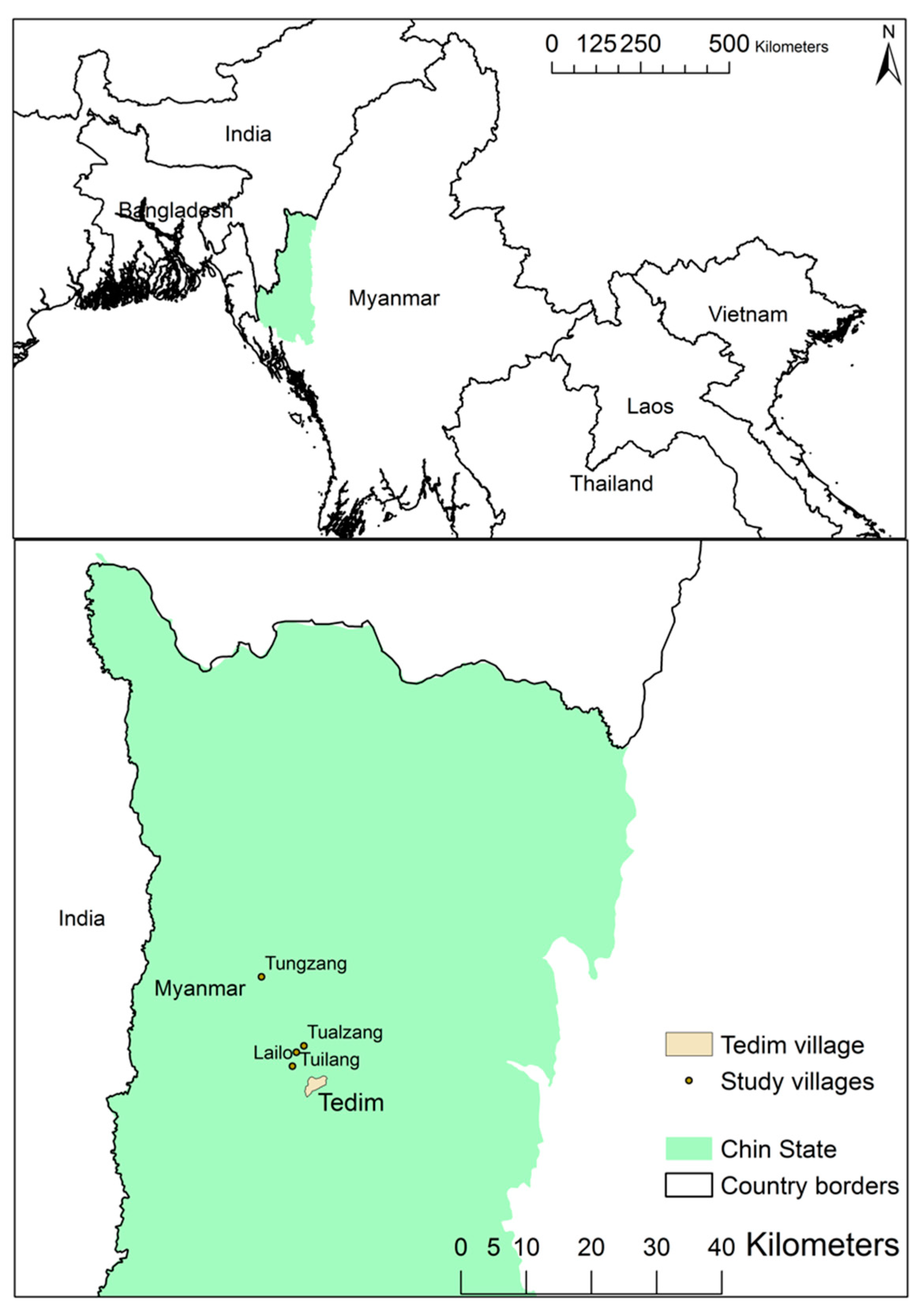

Populations of the study villages differed substantially in size, ranging from approximately 103 to 350 resident households, and 683 to 2400 inhabitants, respectively (

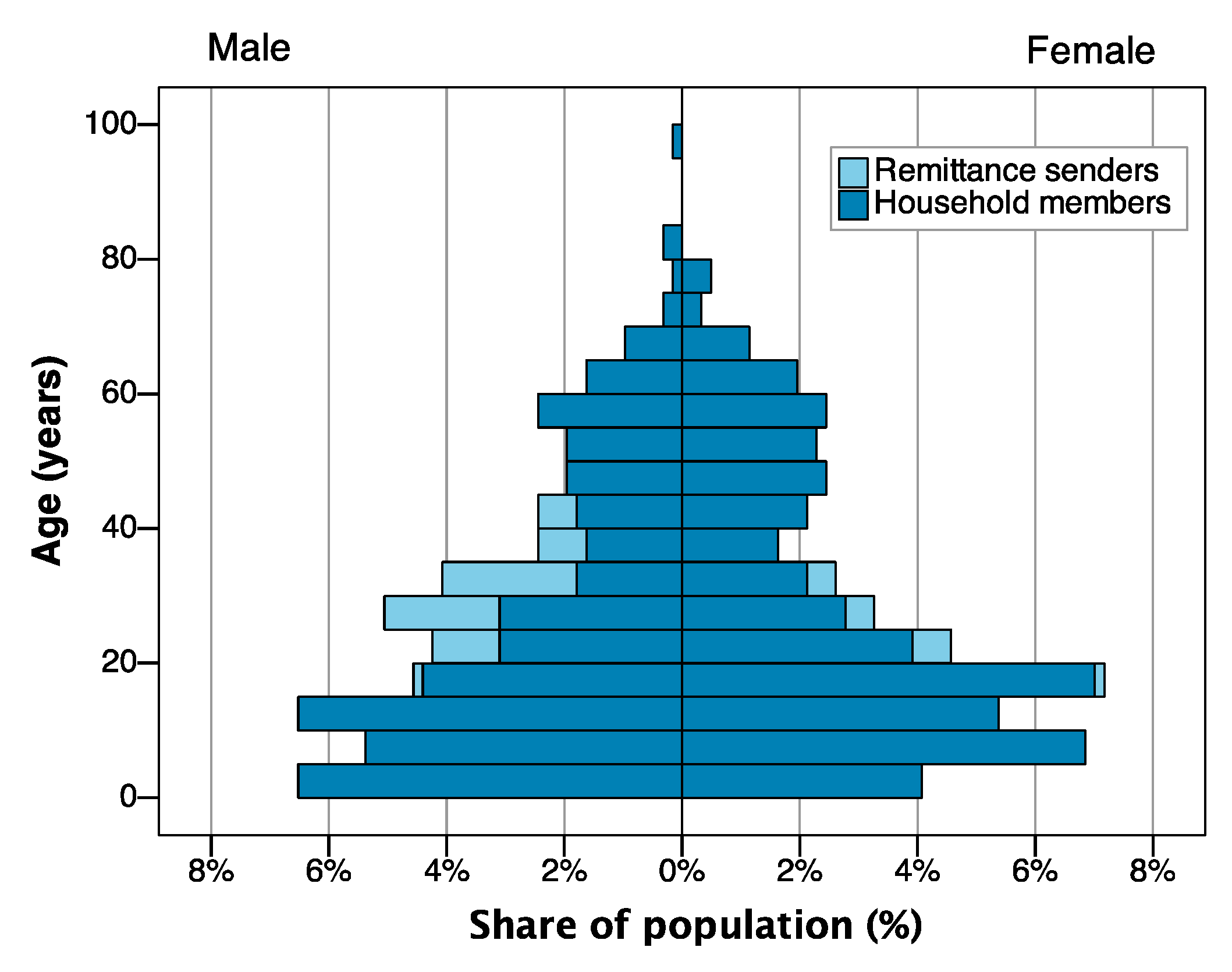

Table 1). The land area under tenure was, however, relatively similar, implying large differences in the ratio of land assets to residents across villages. Village level population records and de facto resident numbers were discrepant across all villages, as official population figures did not account for temporary absent outmigrants, despite migrants’ tendency to remain abroad for several years at a time, or even obtain foreign citizenship. Permanent outmigration of households to Tedim, Kalay or India was common across villages and most pronounced in Tungzang, whereas in-migration had been rare during the past ten years. Populations in all villages had grown in absolute terms over a ten-year period, with local records implying an increase in households and individuals in the range of ≈20–40% and 27–55%, respectively. The average household size in adult equivalent units (AEU) was 3.9 (SD = 1.4). The population structure exhibited high birth rates and dependency ratios across the sample, as well as a pronounced outmigration trend in the 20–40-year age group (

Figure 2). The median dependency ratio was 50% (interquartile range (IQR): 19–150%), and approximately 30% of households had a dependency ratio of more than 100%.

The main decision makers of 79% of the households were married and living together with their spouse; whereas 21% of households were single headed. The average age of household heads was 50.9 years (SD = 13.8), and 13% of households were female headed. The extent of household heads’ schooling was mostly limited. Five percent, fifteen percent, and thirty-two percent of household heads had graduated from high-, secondary-, and primary school, respectively; whereas 31% had not completed primary school, and 17% had not received any formal schooling.

3.2. Livelihood Activities and Associated Income Streams, Aggregated across Sample Households

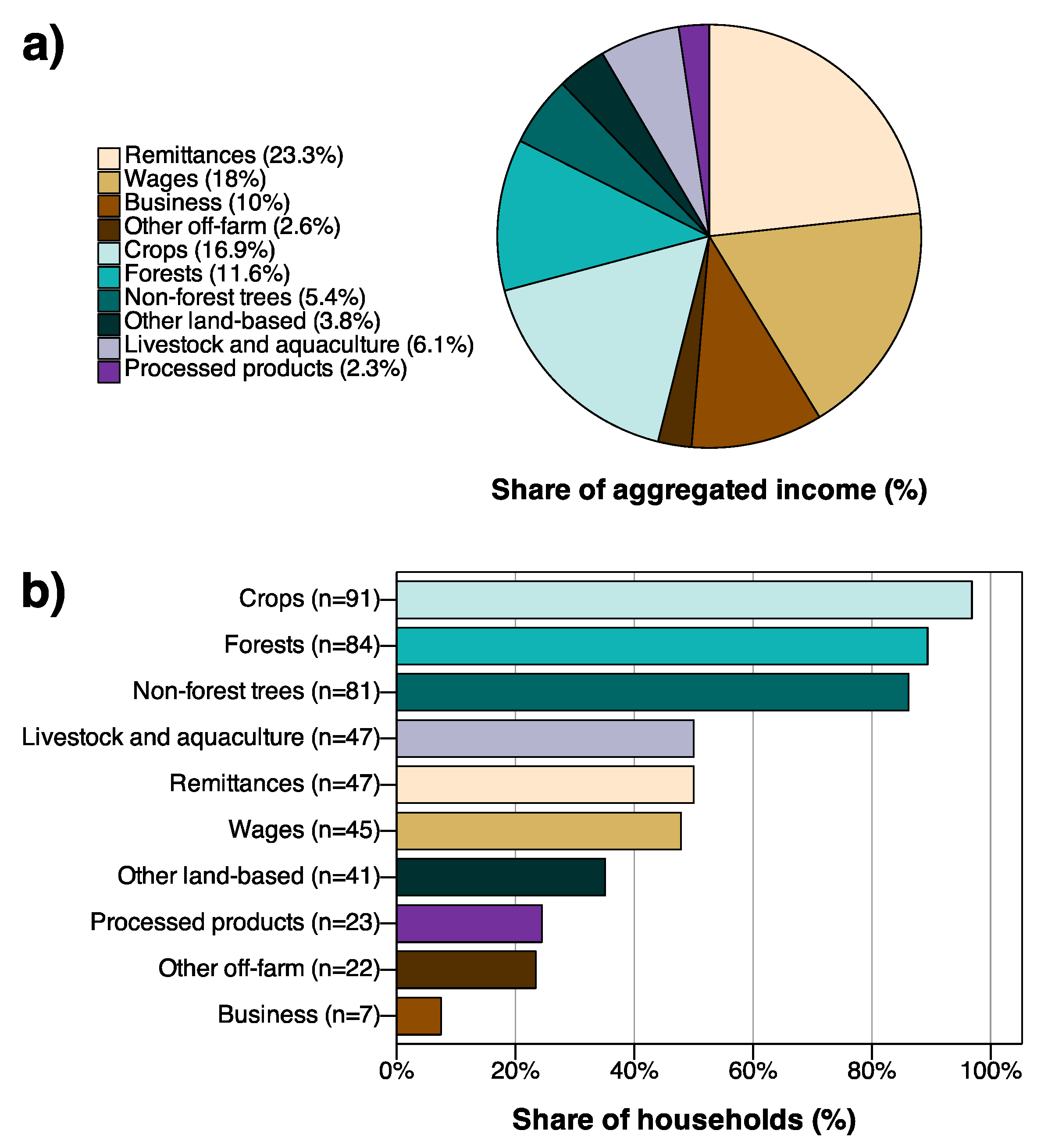

Households’ livelihood activities fell into three broad sectors: (i) Land-based, (ii) off-farm, and (iii) natural resource reliant value adding activities. Activities in the off-farm sector accounted for 54% of households’ realised aggregate income over the studied earning period, whereas income from land-based livelihood activities accounted for a mere 38% (

Figure 3). However, land-based activities were the most common mode of income generation among studied households, with activity rates greater than 80% (

Figure 3).

Remittance payments were the sample’s greatest single source of aggregate income, constituting almost a quarter of households’ aggregate earnings. Fifty percent of sampled households received remittance payments during the studied period, and informal interviews with survey respondents revealed that many households desired to engage in labour migration to realise remittance payments. Remittees, however, also experienced fear to be left behind by younger relatives, without support for physically demanding tasks at old age; and about the possibility of expected payments failing to occur, or being held off, once unmarried female relatives were wed. The mean age of remitters was 29 years (n = 54; SD = 6.3). There was a 4:1 ratio of male to female remitters, and more than 80% of relatives supporting their household financially were either sons or daughters of survey respondents. The mean length of remittance senders’ current stay away from their households of origin was six years (n = 56; SD = 4.8). International destinations of the remitters were Malaysia (n = 24), the United States (n = 17), India (n = 3), Singapore (n = 2) and Australia (n = 1); national destinations included Yangon (n = 4), Mandalay (n = 3) and Tamu (n = 2).

Wage employment was the second most important income sector in absolute terms, constituting 18% of households’ aggregate earnings. Almost half of all sampled households engaged in this livelihood activity, with manual labour, crushing stones for house or road construction and carpentry work as the most common occupations. Construction labour, employment to assist trade to India or locally, as well as manual labour on farms and in forests, or the service industry, offered opportunities for unskilled employment. Skilled employment was rarer, commonly in government roles, as staff in the hospital or health centres, as a school teacher or teaching assistant; or in villages, as a church employee or village electrician.

Self-employed business activities generated 10% of households’ aggregate income, although just seven households engaged in this livelihood activity. Common business activities were the sale of food or clothes. Yet, a carpentry business, the sale of rights to query stones for construction work, and a local transport business, were most remunerative.

Other non-land-based livelihood activities or income sources included the lease of farmland and property, as well as the reception of gifts and support payments from government or civil society actors, and pensions. Twenty-three percent of households received some income of this type, but the magnitude of aggregated income from these sources was rather small.

Cultivation of crops, forest income generation, non-forest tree husbandry and other land-based livelihood activities generated 38% of households’ aggregate income. Only few households did not engage in livelihood activities in this sector, with 97%, 90% and 86% of households realising at least some income from crops, forest and non-forest tree husbandry, respectively. The dominant land-use practice in the study area was annual, rainfed swidden farming on village or private land under customary tenure, with very limited use of external inputs. The spatial and temporal dynamics of this farming practice resulted in characteristic mosaic landscapes, constituted by patches of forests, fallows, and fields in addition to semi-permanent mixed gardens of annual and/or perennial (tree)crops away from homesteads; home gardens; and paddy fields. Households typically maintained a home garden and one or more swidden fields and/or permanent gardens. Commonly cultivated crops included staples, such as maize, paddy rice, millet and a wide variety of legumes, vegetables and fruit-tree crops. Commonly obtained livestock fodder included banana plant material, grasses and tree-leaves. Forest products were commonly obtained from one or more designated fuelwood plots that households maintained individually, and from communal village forests under open access regimes in Tualzang and Tungzang. The majority of households’ plots were not formally titled or registered with state authorities.

Animal husbandry and aquaculture was a common livelihood activity among studied households, but the consumption and sale of animals, animal products and fish from aquaculture made only a minor contribution of 6% to households’ aggregate income. Ninety percent of households owned at least one type of animal, but only 50% of households realised an income from aquaculture or animal husbandry during the studied period. Around 60% of households owned chickens, dogs or pigs, while mithans, cows, goats, horses, buffaloes and ducks were far less common. Smaller animals and pigs were kept within household compounds or home gardens. Larger livestock was free ranging throughout the year, except for animals in Tungzang, which were enclosed on a forest pasture during the monsoon season. Small scale aquaculture was practices by three households.

Processed products contributed 2% to the sample’s aggregate annual income, with 5% of households engaging in respective activities. Distillation of alcohol from rice was the most common cash-oriented value adding activity in this sector. Others included the production of charcoal, local fruit wine, yeast, bamboo chairs and baskets. Households, who processed natural products for subsistence use, mostly produced local fruit wine or stronger rice liquor.

3.3. Income Portfolios and Identified Livelihood Strategies

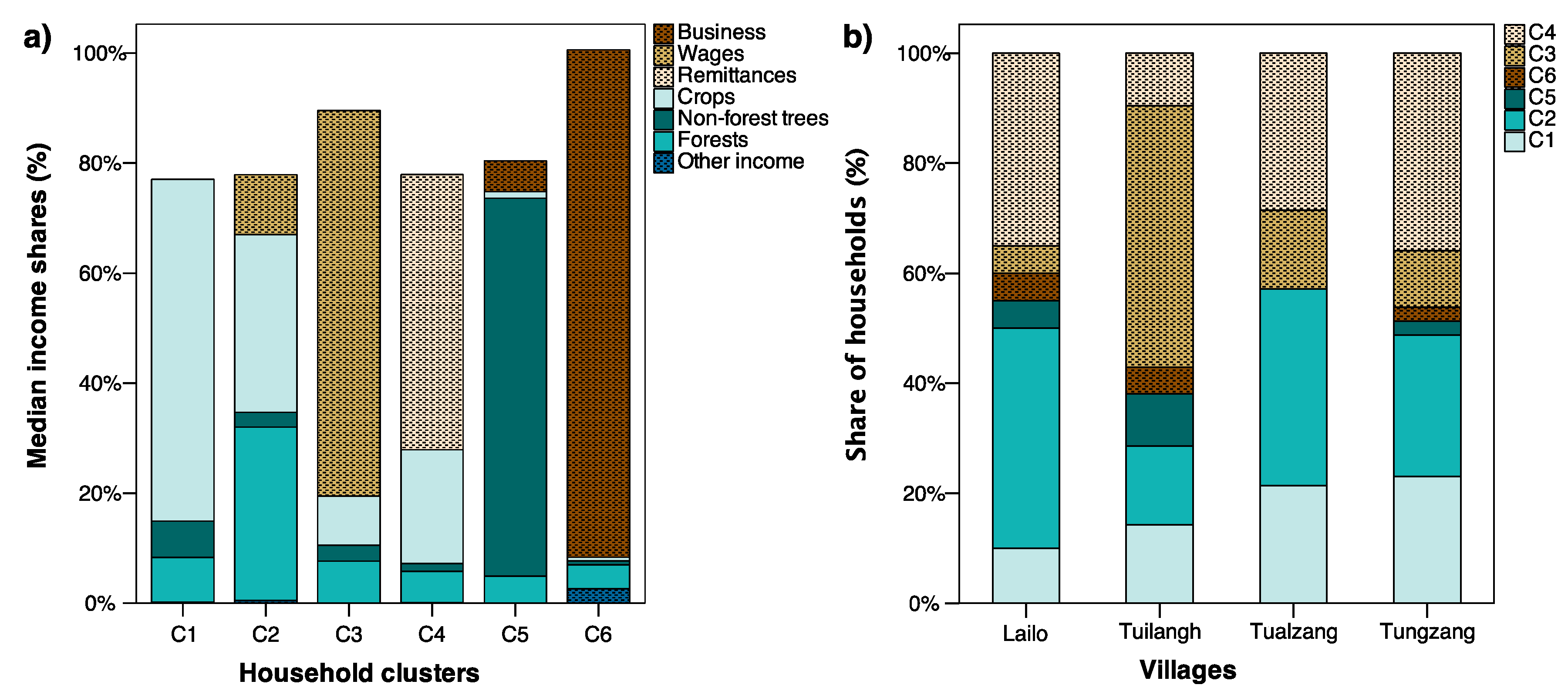

The hierarchical clustering analysis identified six clusters, which we interpret to represent households with relatively distinct income portfolios, i.e., livelihood strategies (

Figure 4): Relying primarily on own farming activities (C1, n = 17); making a living off the land with mixed income from agriculture and forest resources (C2, n = 26); engaging in wage employment (C3, n = 17); living from remittances (C4, n = 27); practicing non-forest tree husbandry (C5, n = 4); or engaging in self-employed business activities (C6, n = 3). Judging from field experience, the latter two clusters constituted meaningful groups of cases, rather than outliers. Yet, these households were excluded from tests to detect statistical differences across clusters, due to the small number of cases representing the respective livelihood strategies and are therefore not represented in Figure 6,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4 and Appendixes

Table A2 and

Table A3.

Households in C1, C2 and C5 relied primarily on land-based livelihood activities, whereas households in C3, C4 and C6 relied primarily on income streams from off-farm activities (

Figure 4).

Table 2 and

Table A2 show the distribution and statistically significant differences of relative income shares from various livelihood activities across clusters C1–C4. Cultivated crops were an important income source for household in C1 and C2, who tended to derive the greatest and second greatest proportions of income from crops among all clusters. Households in C2 derived a second main household income component from forests; with a median forest income share exceeding that of other groups by at least a factor of four. Wages constituted the greatest income source of households in C3; whereas households in C4 gained substantial incomes from remittance payments. Households in C5 relied primarily on income from non-forest tree husbandry, in stark contrast to all other clusters. Moreover, only households in C6 derived more than 14% of their income from self-employed business activities, realising a respective median income share of 92%.

A Kruskal-Wallis-H test and post-hoc analysis verified inter-cluster disparities of household income portfolios, revealing statistically significant between-group differences in the distributions of income shares from wages (H(3) = 53.053,

p < 0.001), remittances (H(3) = 62.935,

p < 0.001), crops (H(3) = 51.807,

p < 0.001), and forests (H(3) = 38.545,

p < 0.001) across clusters C1–C4 (

Table 2,

Table A2).

The distribution of clusters across villages was relatively equal, except for Tuilangh, where a disproportionate number of households relied on wage employment, but relatively few houses relied on remittance payments or mixed income from agriculture and forest resources. In Tualzang, none of the households engaged in self-employed business activities or non-forest tree husbandry.

3.4. Absolute Income Distribution and Income-Poverty across Clusters

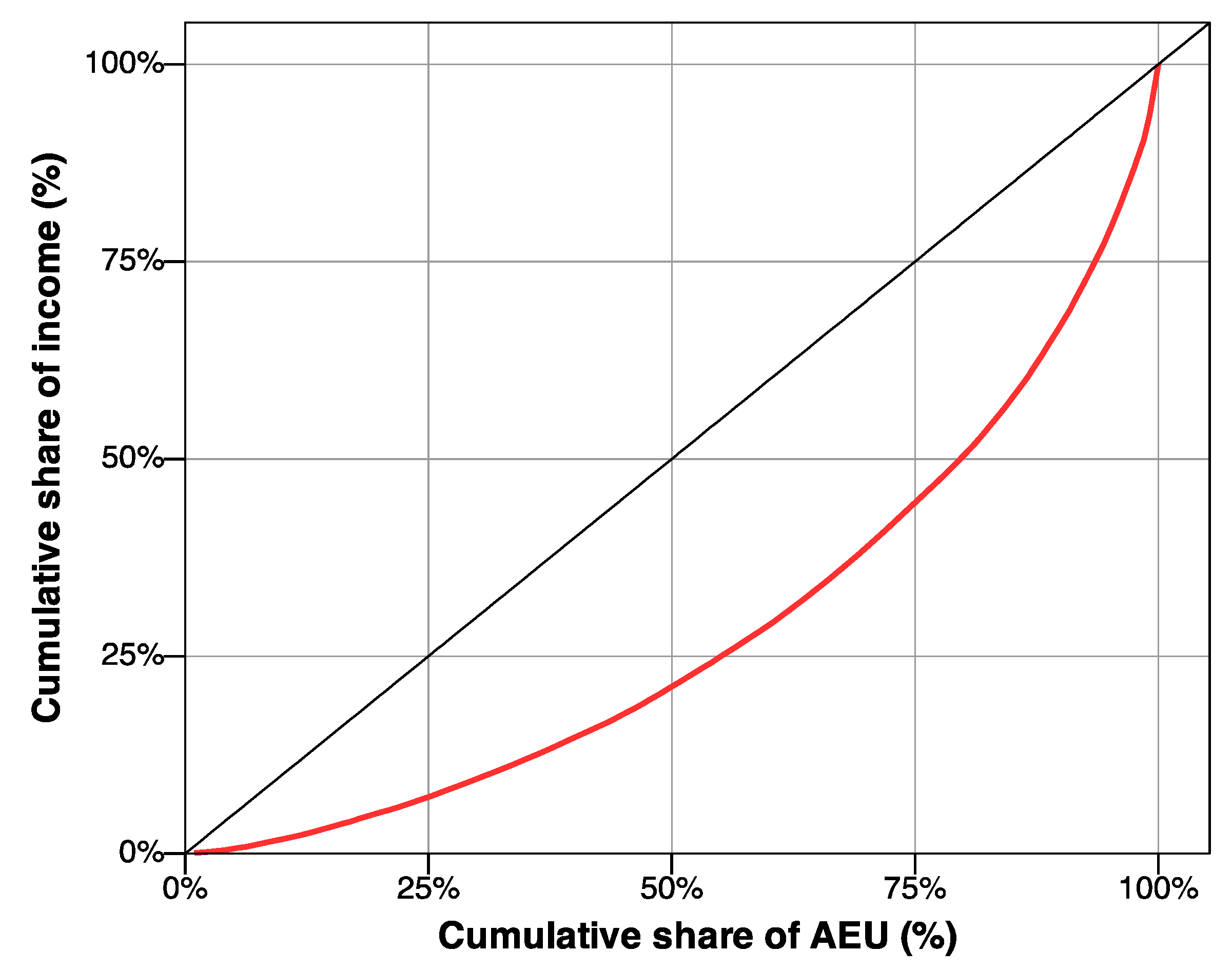

The median aggregate annual income per AEU across all households was 468 thousand Myanmar Kyat (MMK) (IQR: 281–750 thousand MMK) (1000 MMK~0.68 USD in 2018), but income inequalities across different households and livelihood strategies were pronounced (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). Households representing 50% of AEU in the sample realised less than 25% of generated household income, whereas the top 25% of adult equivalent units obtained more than 50% of all income realised by the sample population.

A Kruskal-Wallis test with subsequent post-hoc analysis (

Table 3,

Table A3) and cumulative frequency distributions (

Figure 6) revealed that off-farm oriented livelihood strategies tended to be more remunerative than land-based strategies. Households in C4 had the greatest median aggregate annual income per AEU, followed in descending order by households in C3, C2 and C1 (

Table 3). However, if households in C4 would not have received remittances, they would have realised very similar incomes to those in C1 and C2—as absolute income portfolios of household in C1 and C4 were composed very similarly, except for remittance income shares that lifted most households in C4 out of poverty.

Distributions of absolute realised incomes from different sources across livelihood strategies (

Table 3), overall, followed similar patterns to those observed for relative income shares (

Table 2). Households in C3 and C4 realised the greatest median absolute incomes, from wage employment and remittance payments of 496.2 and 329.2 thousand MMK per AEU, respectively. Households in C2 realised a median absolute forest income of 97.2 thousand MMK per AEU, which was significantly greater than forest incomes realised by C1, C3 and C4. Households across clusters C1–C4 realised moderate incomes from non-forest tree husbandry, but no significant differences in the magnitude of these income streams were observed among households in these groups. Realised incomes from livestock and processed products were typically small compared to households’ aggregate absolute incomes, but a few households in C1–C4 realised comparably substantial incomes from cash crops. The differences in absolute incomes from livestock, processed products and cash crops among households were, however, not well explained by cluster membership.

Household incomes were most equally distributed in C1 (

Figure 6), whereas distributive income inequalities were more pronounced in C2–C4. Non-forest tree husbandry was a livelihood strategy that both very income poor and comparatively income rich households relied on, with realised annual incomes per AEU in the range of 71 to 1017 thousand MMK. However, the income range between the income poorest and richest household was greatest in C6, spanning from 472 to 4457 thousand MMK per AEU and year. More than 90% of the AEU in C1 lived below the international poverty line of less than 1.90 USD purchasing power parity (PPP); whereas households in clusters C2–C4 fell far less frequently below this poverty line, with well under 60%, 40% and 20% of AEU realising daily incomes of less than 1.90 USD PPP.

3.5. Households’ Self-Reported Welfare

The majority of respondents felt very satisfied (7%), satisfied (40%) or at least neutral (40%) about their household’s overall welfare, but 58% and 37% of all study households did not have sufficient, or barely sufficient cash to meet their needs, respectively. The self-perceived trend of household welfare over a five-year period was positive for a majority of respondents. Forty-four percent, thirty percent and twenty-six percent of respondents reported improved, stable or declined welfare status of their household, respectively. Twelve of the 42 respondents who reported welfare gains for their household attributed these changed circumstances to remittance payments. Only two of 24 respondents, who reported that their household’s welfare had decreased, in contrast, identified the non-arrival of expected remittance payments as the primary cause of the experienced decline. Overall increased household income, engagement in wage employment, and increased household labour availability as children grew up, were other important reasons for perceived welfare improvements; whereas engagement in cash crop cultivation, livestock husbandry and the expansion of land under cultivation were named by just four households. Decreased household welfare was most often attributed to decreased labour availability, due to old age, bad health, births or the marriage of mature children. Other reasons included increased household expenses to meet the needs of young children or household members in ill health. Or the death of, or divorce from the male head of a household.