Climate Change, Agriculture, and Economic Development in Ethiopia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Climate Change Impact Scenarios

2.2. Climate Change and Crop Productivity

2.3. Climate Change and Livestock Productivity

2.4. Climate Change and Agricultural Labor Migration

2.5. Structural Change Scenarios

2.5.1. Improving Labor Skills

2.5.2. Declining Marketing Margins

2.6. The CGE Model Calibration and Regional Projections

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Economic Effects of Climate Change without Structural Change

3.1.1. Country-Wide Effects

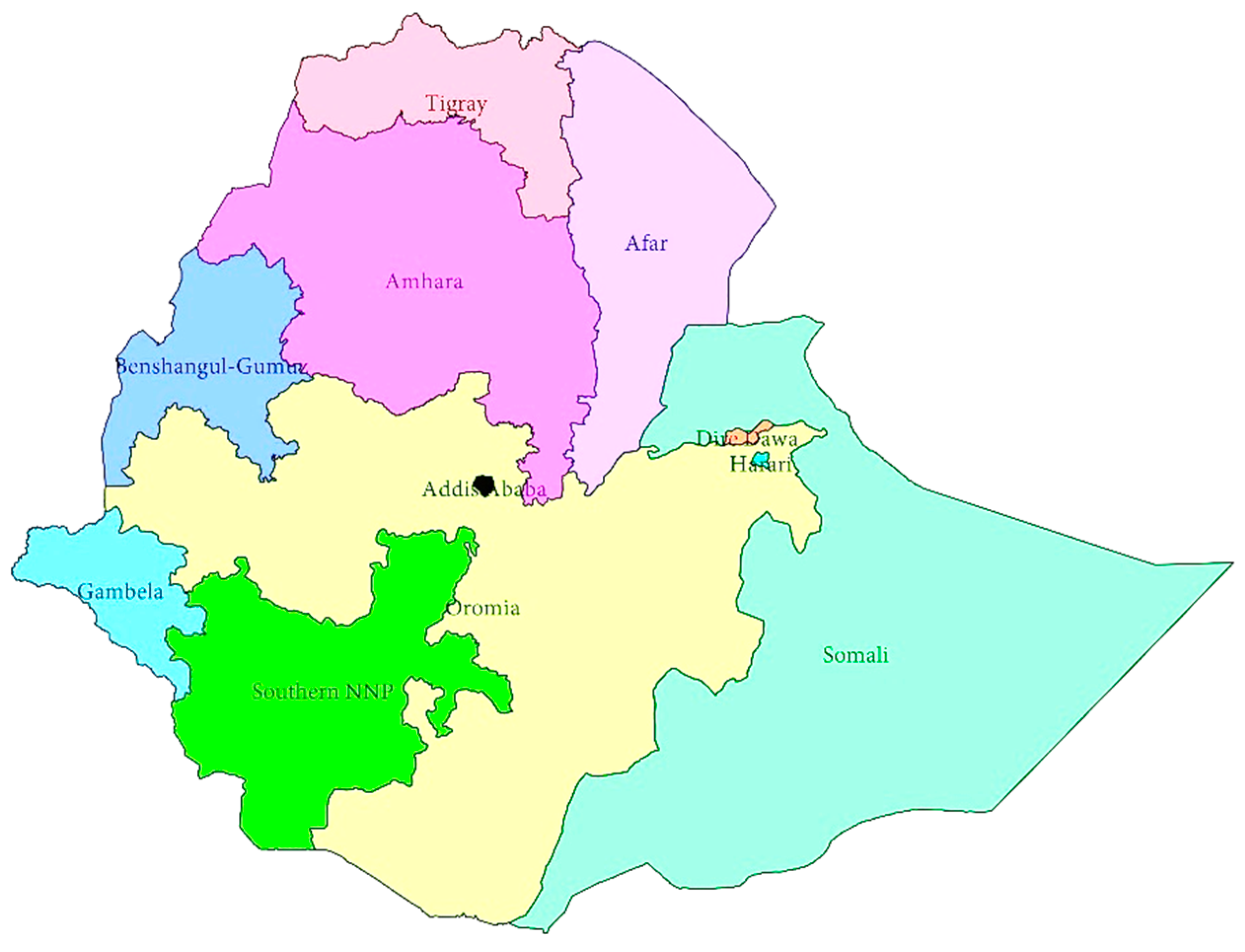

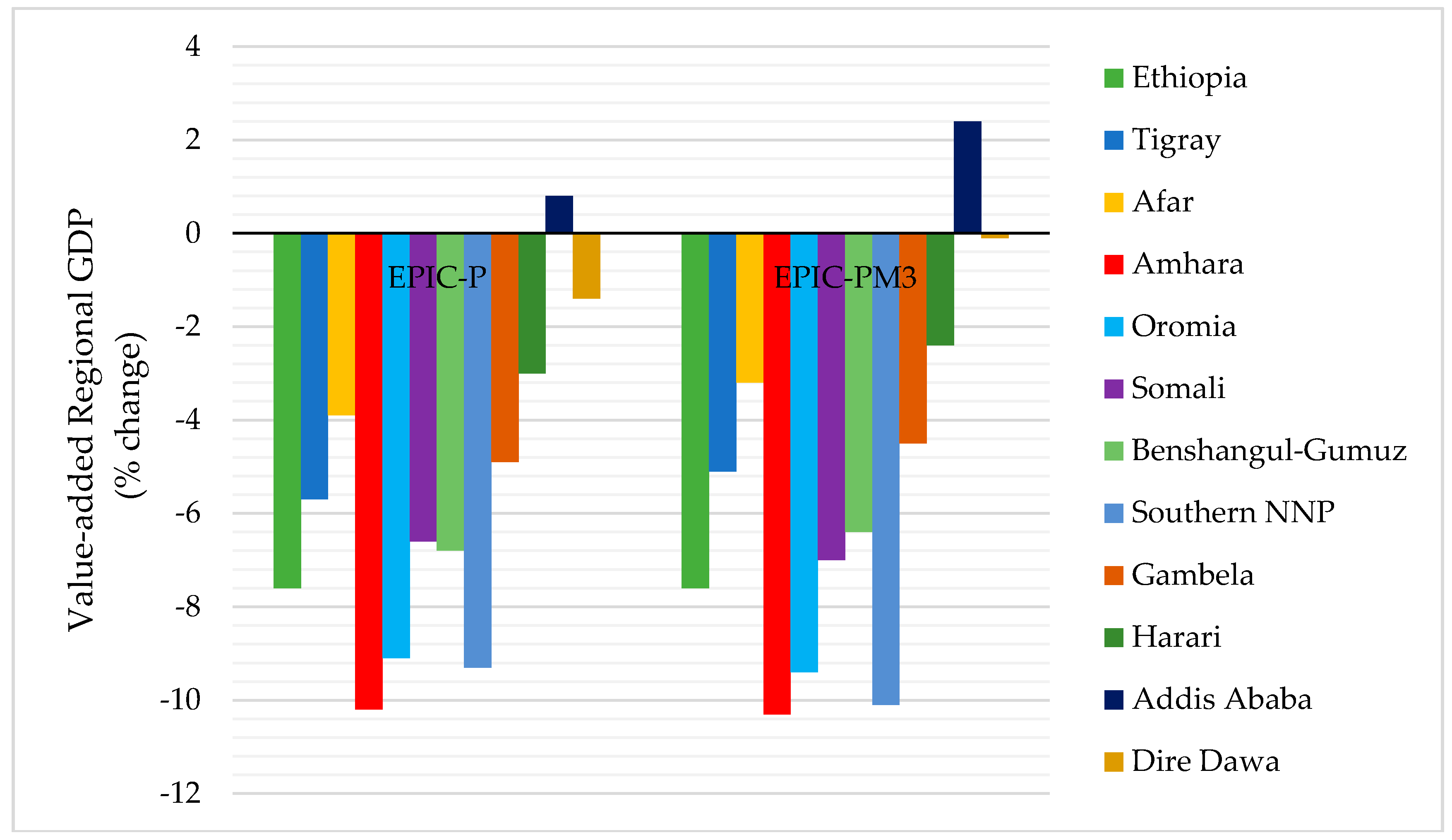

3.1.2. Regional Effects

3.2. Economic Effects of Climate Change with Structural Change

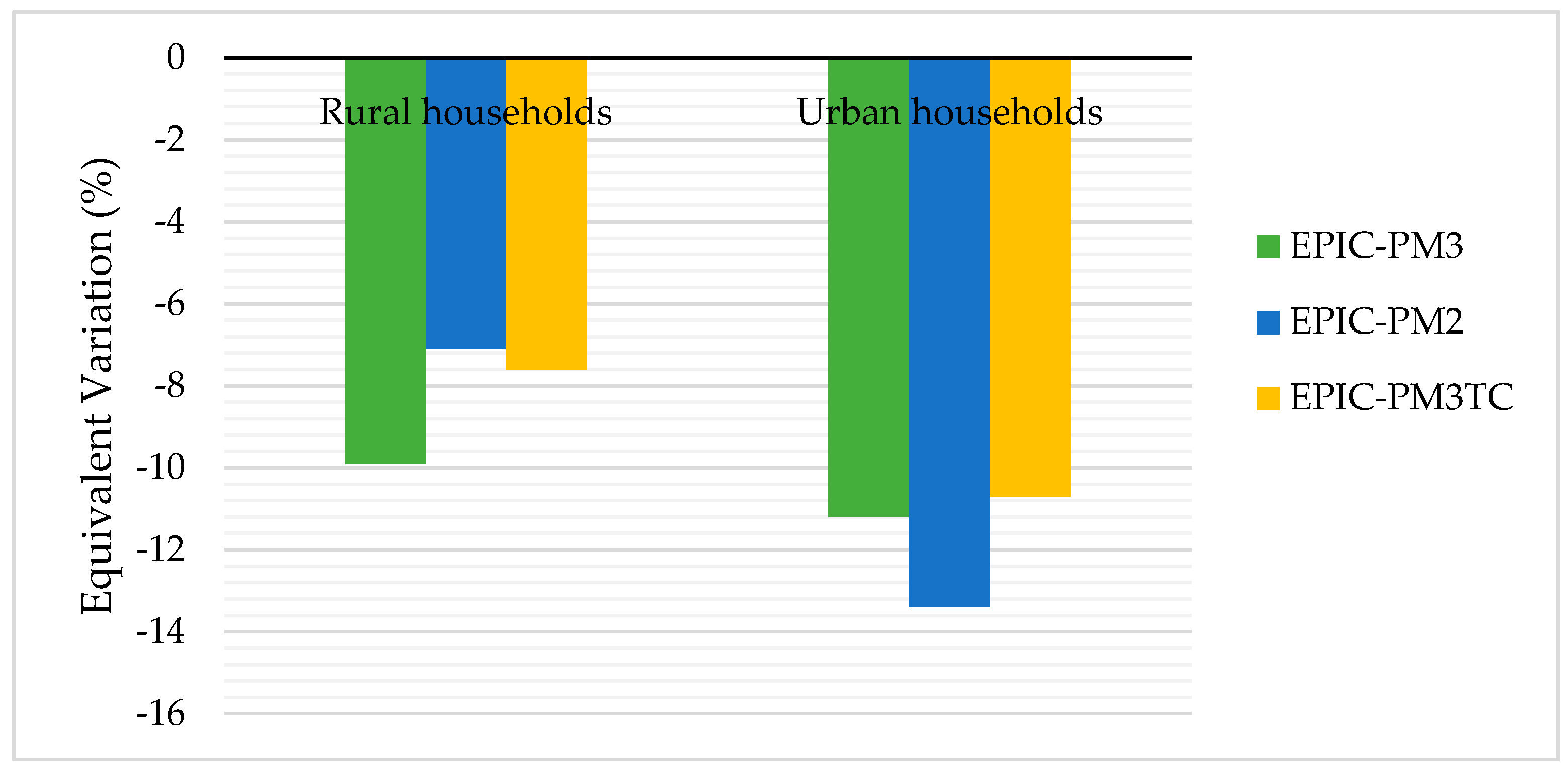

3.2.1. Country-Wide Effects

3.2.2. Regional Effects

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A.

Appendix A.1. Livestock Productivity Changes

Appendix A.2. Brief Description of the CGE Model Structure and Calibration

- Perfect competition in commodity and factor markets.

- A small-open economy with respect to international trade.

- Imperfect transformation between domestic sales and exports, and imperfect substitution between domestic output and imports.

- Producers, households, enterprises, government, and rest of the world represent decision-making nodes in the CGE model.

- Producers’ decisions are guided by a profit maximization goal subject to the output and input prices, and the production technology. Each producer face a two-stage production technology nest (see Figure A2). The Leontief (LEO) function combines the aggregate value-added and the aggregate intermediate input at the top of the production technology nest. The aggregate value-added nest is a composite of the primary factors of production aggregated using a constant elasticity of substitution (CES) function. The aggregate intermediate input is a composite of different intermediate commodities combined using a Leontief function.

- Every producer is allowed to produce one or more commodities that can be consumed at home (home commodities) or sold at markets (market commodities). The producers’ decision to sell market commodities in domestic or foreign markets is guided by a profit maximization goal constrained by a constant elasticity of transformation (CET) function.

- Households receive income from factors of production they own directly (e.g., labor) and indirectly (e.g., capital through enterprises), remittances from abroad, and transfers from the government. Households pay direct taxes, remit to abroad, transfer to the other household group, save, and spend on consumption. The consumption demand of households on consumption is specified by the linear expenditure system (LES). Households are allowed to consume both home commodities (valued at producer prices) and market commodities (valued at sales prices). The consumption bundle of households includes both domestic and foreign varieties of goods aggregated using a CES function.

- The values of the elasticities are collected from the empirical literature. The values of elasticities of factor substitution increase from agricultural activities to service activities, and income elasticities of demand increase from agricultural commodities to services commodities. The elasticities of export transformation and import substitution increase with tradability of the commodities. We set the absolute value of the Frisch parameter to 2 (for rural households) and to 1.5 (for urban households).

- All factors are assumed to be fully employed. For each factor, an economy-wide wage rate is flexible to assure that the sum of factor demands is equal to the fixed (observed) quantity of factor supply. All categories of labor and land are assumed to be mobile across activities whereas livestock and capital are activity-specific. We obtain the observed employment of each labor category by activity from [39]. We use the [32] to allocate the total agricultural labor among the five agricultural activities of the modified SAM, and to compute the tropical livestock unit (TLU, a factor used only in the livestock activity). We set the average wage rate of capital factor equal to unity. Thus, the observed employment of capital per activity is represented by the payment from the activity to capital factor in the SAM.

- The combination of the macroeconomic closures is the ‘Johansen’ type [54]. For the external sector balance, the real exchange rate is flexible while the foreign saving is fixed. The government’s saving adjusts to maintain the balance between the government’s revenue and recurrent expenditure. All tax rates and real government consumption of goods and services are fixed. The saving-investment (S-I) balance closure is investment-driven.

- The consumer price index (CPI) is the numeraire of the model. All simulated changes shall be interpreted relative to this numeraire.

| Elasticities | Applied for | Values |

|---|---|---|

| Elasticities of factor substitution | All activities | 0.3–2.0 |

| Elasticities of import substitution | All import goods | 0.5–2.0 |

| Elasticities of export transformation | All export goods | 0.5–2.0 |

| Income elasticities | All household consumption goods | 0.7–1.5 |

| Frisch parameter (absolute value) | Both household groups | 1.5–2.0 |

Appendix A.3. Regional Module and Projections

- We apply a simple rule to disaggregate the Ethiopia-wide sectoral output to obtain regional sectoral output. We find the employment data to be relatively comprehensive and easy to map with the SAM. We take a regional share in Ethiopia-wide sectoral employment as proxy to a regional share in Ethiopia-wide sectoral output. Our main source of employment data, per industry, in each region is [39]. We made adjustments. We used the population and housing census [61] to control for a possible sampling bias in the labor force survey [39]. We use [32] to adjust employment among agricultural activities. We use the government expenditure on agriculture and rural development in each region [62] to compute regional shares in activity of public administration (agriculture) services (i.e., public admin. (agri.) in Table A2 below).

- We compute the sector-wise output of the 17 activities for each region based on the regional shares from the previous step. Summing the regional sector-wise outputs gives the region-wide GDP for each region.

- To check the robustness of the regional module, we apply the same procedures using employment data from [73] instead of [39]. The economic structure of many regions remain more or less. Only the case with Tigray region where the employment in manufacturing activity in [73] is lower than what is reported in [39] was an exception. Thus, the regional module based on the former increases the role of agriculture in Tigray region. There are no noticeable differences in the rest of the regions. We retain the case with data from [39] as it is also used for creating the original SAM [34].

| Notation | Description | ETH | Region | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIG | AFR | AMH | ORM | SOM | BNG | SNNP | GAM | HAR | ADD | DD | |||

| AGRAIN | Grain crops | 18 | 21 | 7 | 34 | 21 | 8 | 26 | 13 | 11 | 5 | 0 | 3 |

| ACCROP | Cash crops | 10 | 2 | 7 | 7 | 12 | 7 | 5 | 19 | 15 | 9 | 0 | 3 |

| AENSET | Enset crop | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ALIVST | Livestock | 14 | 5 | 15 | 12 | 20 | 13 | 3 | 20 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| AFISFOR | Fishing & forestry | 5 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 25 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AMINQ | Mining & quarrying | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| ACONS | Construction | 4 | 14 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 15 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 8 |

| AMAN | Manufacturing | 7 | 7 | 12 | 9 | 7 | 3 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 7 | 4 |

| ATSER | Wholesale & retail trade | 11 | 9 | 12 | 7 | 12 | 14 | 9 | 12 | 18 | 27 | 12 | 27 |

| AHSER | Hotels & restaurants | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| ATRNCOM | Transport & comm. | 5 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 10 | 19 | 22 |

| AFSER | Financial intermediaries | 2 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 4 |

| ARSER | Real estate & renting | 8 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 9 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 25 | 10 |

| APADMN | Public admin. (general) | 4 | 13 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 9 | 14 | 7 | 4 |

| APAGRI | Public admin. (agri) | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| ASSER | Social services | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 7 | 13 | 7 | 5 |

| AOSER | Other services | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 6 |

| TOTAL | Total GDP at factor cost | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

References

- Müller, C.; Waha, K.; Bondeau, A.; Heinke, J. Hotspots of climate change impacts in sub-Saharan Africa and implications for adaptation and development. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2014, 20, 2505–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hertel, T.W.; Lobell, D.B. Agricultural adaptation to climate change in rich and poor countries: Current modeling practice and potential for empirical contributions. Energy Econ. 2014, 46, 562–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, J.; Hess, T.; Daccache, A.; Wheeler, T. Climate change impacts on crop productivity in Africa and South Asia. Environ. Res. Lett. 2012, 7, 034032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schlenker, W.; Lobell, D.B. Robust negative impacts of climate change on African agriculture. Environ. Res. Lett. 2010, 5, 014010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nelson, G.C.; Rosegrant, M.W.; Koo, J.; Robertson, R.; Sulser, T.; Zhu, T.; Lee, D. The Costs of Agricultural Adaptation to Climate Change; Development and Climate Change Discussion Paper No. 4; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R.M.; Hurd, B.H.; Lenhart, S.; Leary, N. Effects of global climate change on agriculture: An interpretative review. Clim. Res. 1998, 11, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P.K.; van de Steeg, J.; Notenbaert, A.; Herrero, M. The impacts of climate change on livestock and livestock systems in developing countries: A review of what we know and what we need to know. Agric. Syst. 2009, 101, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardone, A.; Ronchi, B.; Lacetera, N.; Ranieri, M.S.; Bernabucci, U. Effects of climate changes on animal production and sustainability of livestock systems. Livest. Sci. 2010, 130, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.N.; Mendelsohn, R. Measuring impacts and adaptations to climate change: A structural Ricardian model of African Livestock management. Agric. Econ. 2008, 38, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antle, J.M.; Capalbo, S.M. Adaptation of agricultural and food systems to climate change: An economic and policy. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2010, 32, 386–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubik, Z.; Mathilde, M. Weather shocks, agricultural production and migration: Evidence from Tanzania. J. Dev. Stud. 2016, 52, 665–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertz, O.; Mbow, C.; Reenberg, A.; Genesio, L.; Lambin, E.F.; D’haen, S.; Sandholt, I. Adaptation strategies and climate vulnerability in the Sudano-Sahelian region of West Africa. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 2011, 12, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Naude, W. The determinants of migration from sub-Saharan African Countries. J. Afr. Econ. 2010, 19, 330–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, O. Migration and Climate Change; IOM Migration Research Series, No. 31; International Organization for Migration: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- McLeman, R.; Smit, B. Migration as an adaptation to climate change. Clim. Chang. 2006, 76, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagidede, P.; Adu, G.; Frimpong, P.B. The effect of climate change on economic growth: Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa. Environ. Econ. Policy Stud. 2016, 18, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell, M.; Jones, B.F.; Olken, B.A. Temperature shocks and economic growth: Evidence from the last half century. Am. Econ. J. Macroecon. 2012, 4, 66–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, B.F.; Olken, B.A. Climate shocks and exports. Am. Econ. Rev. Pap. Proc. 2010, 100, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Change Knowledge Portal. Available online: http://data.worldbank.org/country/ethiopia (accessed on 24 September 2016).

- Conway, D.; Schipper, E.F. Adaptation to climate change in Africa: Challenges and opportunities identified from Ethiopia. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassie, B.T. Climate Variability and Change in Ethiopia: Exploring Impacts and Adaptation Options for Cereal Production. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Admassu, G.; Getinet, M.; Thomas, T.S.; Waithaka, M.; Kyotalimye, M. Ethiopia. In East African Agriculture and Climate Change: A Comprehensive Analysis; Waithaka, M., Nelson, G.C., Thomas, T.S., Kyotalimye, M., Eds.; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; pp. 149–182. [Google Scholar]

- Evangelista, P.; Young, N.; Burnett, J. How will climate change spatially affect agriculture production in Ethiopia? Case studies of important cereal crops. Clim. Chang. 2013, 119, 855–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deressa, T.T.; Hassan, R.M. Economic impact of climate change on crop production in Ethiopia: Evidence from cross-section measures. J. Afr. Econ. 2009, 18, 529–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, C.; Robinson, S.; Willenbockel, D. Ethiopia’s growth prospects in a changing climate: A stochastic general equilibrium approach. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Economics of Adaptation to Climate Change: Ethiopia; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- AgMIP Tool: A GEOSHARE Tool for Aggregating Outputs from the AgMIP’s Global Gridded Crop Modeling Initiative (Ag-GRID). Available online: https://mygeohub.org/resources/agmip (accessed on 24 November 2015).

- Moss, R.H.; Edmonds, J.A.; Hibbard, K.A.; Manning, M.R.; Rose, S.; van Vuuren, D.P.; Wilbanks, T.J. The next generation of scenarios for climate change research and assessment. Nature 2010, 463, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenzweig, C.; Elliott, J.; Deryng, D.; Ruane, A.C.; Müller, C.; Arneth, A.; Jones, J.W. Assessing agricultural risks of climate change in the 21st century in a global gridded crop model intercomparison. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 111, 3268–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Müller, C.; Robertson, R.D. Projecting future crop productivity for global economic modeling. Agric. Econ. 2014, 45, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annual Agricultural Sample Survey (AgSS); Central Statistics Agency: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2014. Available online: www.csa.gov.et (accessed on 15 November 2015).

- Annual Agricultural Sample Survey (AgSS); Central Statistics Agency: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2006. Available online: www.csa.gov.et (accessed on 15 November 2015).

- Ethiopia’s Agricultural Sector Policy and Investment Framework: 2010–2020; Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MoARD): Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2010.

- Input-output Table and Social Accounting Matrix; Ethiopian Development Research Institute (EDRI): Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2009.

- Agricultural Sample Survey Time Series Data for National and Regional Level: From 1995/96–2014/15: Report on Crop Area and Production; Central Statistics Agency: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2015. Available online: www.csa.gov.et (accessed on 20 April 2016).

- Robinson, S.; Strzepek, K.; Cervigni, R. The Cost of Adapting to Climate Change in Ethiopia: Sector-Wise and Macro-Economic Estimates; ESSP II Working Paper No. 53; Ethiopia Strategic Support Program II; Ethiopian Development Research Institute (EDRI): Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Weindl, I.; Lotze-Campen, H.; Popp, A.; Müller, C.; Havlík, P.; Herrero, M.; Rolinski, S. Livestock in a changing climate: Production system transitions as an adaptation strategy for agriculture. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 094021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Labor Force Survey; Central Statistics Agency: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2013. Available online: www.csa.gov.et (accessed on 14 December 2015).

- National Labor Force Survey; Central Statistics Agency: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2005. Available online: www.csa.gov.et (accessed on 14 December 2015).

- National Labor Force Survey; Central Statistics Agency: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 1999. Available online: www.csa.gov.et (accessed on 14 December 2015).

- Inter-Censal Population Survey; Central Statistics Agency: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2012. Available online: www.csa.gov.et (accessed on 14 December 2015).

- Gebeyehu, Z.H. Land Policy Implications in Rural-Urban Migration: The Dynamics and Determinant Factors of Rural-Urban Migration in Ethiopia. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität München, Munich, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, C.; Mueller, V. Drought and population mobility in rural Ethiopia. World Dev. 2012, 40, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miheretu, B.A. Causes and Consequences of Rural-Urban Migration: The Case of Woldiya Town, North Ethiopia. Master’s Thesis, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dercon, S. Growth and shocks: Evidence from rural Ethiopia. J. Dev. Econ. 2004, 74, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezra, M. Demographic response to environmental stress in drought- and famine-prone areas of northern Ethiopia. Int. J. Popul. Geogr. 2001, 7, 259–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezra, M.; Kiros, G.E. Rural out-migration in the drought prone areas of Ethiopia: A multilevel analysis. Int. Migr. Rev. 2001, 35, 749–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Bank Annual Report 2014–2015; National Bank of Ethiopia: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2016. Available online: http://www.nbe.gov.et/publications/annualreport.html (accessed on 12 January 2017).

- Growth and Transformation Plan II: 2015/16–2019/20; National Planning Commission of Ethiopia: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2016.

- Universal Rural Road Access Program; Ethiopian Roads Authority: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2010. Available online: http://www.era.gov.et/documents/10157/72095/UNIVERSAL+RURAL+ROAD+ACCESS+PROGRAM.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2015).

- Yalew, A.W.; Hirte, G.; Lotze-Campen, H.; Tscharaktschiew, S. Economic Effects of Climate Change in Developing Countries: Economy-Wide and Regional Analysis for Ethiopia; Working Paper 10/17; CEPIE: Dresden, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gabre-Madhin, E.Z. Market Institutions, Transaction Costs, and Social Capital in the Ethiopian Grain Market; Research Report No. 124; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Stifel, D.; Minten, B.; Koru, B. Economic benefits of rural feeder roads: Evidence from Ethiopia. J. Dev. Stud. 2016, 52, 1335–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lofgren, H.; Harris, L.R.; Robinson, S. A Standard Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) Model in GAMS; Microcomputers in Policy Research No. 5; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; Available online: www.ifpri.org/publication/standard-computable-general-equilibrium-cge-model-gams-0 (accessed on 10 July 2014).

- Robinson, S.; Willenbockel, D.; Strzepek, K. A dynamic general equilibrium analysis of adaptation to climate change in Ethiopia. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2012, 16, 489–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielke, R. Mistreatment of the economic impacts of extreme events in the Stern Review Report on the Economics of Climate Change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2007, 17, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yalew, A.W.; Hirte, G.; Lotze-Campen, H.; Tscharaktschiew, S. General Equilibrium Effects of Public Adaptation in Agriculture in LDCs: Evidence from Ethiopia; Working Paper 11/17; CEPIE: Dresden, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Higgs, P.J.; Parmenter, B.R.; Rimmer, R.J. A hybrid top-down, bottom-up regional computable general equilibrium model. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 1988, 11, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, P.B.; Parmenter, B.R.; Sutton, J.; Vincent, D.P. ORANI: A Multisectoral Model of the Australian Economy; North-Holland Publishing Co.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Naqvi, F.; Peter, M.W. A multiregional, multisectoral model of the Australian economy with an illustrative application. Aust. Econ. Pap. 1996, 35, 94–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Population and Housing Census (PHC); Central Statistical Agency: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2007. Available online: www.csa.gov.et (accessed on 24 September 2018).

- Quarterly Government Finance: National and Regional Budgets; Ministry of Finance and Economic Development (MoFED): Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2015.

- Wondimagegnhu, B.A. Staying or leaving? Analyzing the rationality of rural-urban migration associated with farm income of staying households: A case study from Southern Ethiopia. Adv. Agric. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brauw, A. Migration, Youth, and Agricultural Productivity in Ethiopia. 2014. Available online: http://ageconsearch.umn.edu//handle/189684 (accessed on 24 September 2016).

- De Boer, P.; Missaglia, M. Estimation of Income Elasticities and Their Use in a CGE Model for Palestine; Repot No. 12; Econometric Institute, Erasmus University Rotterdam: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; Available online: http://repub.eur.nl/pub/7753 (accessed on 15 January 2016).

- Von Braun, J. A Policy Agenda for Famine Prevention in Africa; Food Policy Statement No. 13; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Growth and Transformation Plan: 2010/11–2014/15; Ministry of Finance and Economic Development (MoFED): Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2010.

- Dorosh, P.; Thurlow, J. Urbanization and Economic Transformation: A CGE Analysis for Ethiopia; ESSP II Working Paper No. 14; Ethiopia Strategy Support Program II; Ethiopian Development Research Institute (EDRI): Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fankhauser, S.; Schmidt-Traub, G. From adaptation to climate-resilient development: The costs of climate-proofing the millennium development goals in Africa. Clim. Dev. 2011, 3, 94–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.V.; Storeygard, A.; Deichmann, W. Has climate change driven urbanization in Africa? J. Dev. Econ. 2017, 124, 60–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Millner, A.; Dietz, S. Adaptation to climate change and economic growth in developing Countries. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2015, 20, 380–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendelsohn, R. The economics of adaptation to climate change in developing Countries. Clim. Chang. Econ. 2012, 3, 1250006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Household Income, Consumption, and Expenditure Survey (HICES); Central Statistics Agency: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2005. Available online: www.csa.gov.et (accessed on 14 December 2015).

| Simulation | Description |

|---|---|

| LPJmL-P | −10% and −2% productivity effects on grain and livestock activities, respectively |

| EPIC-P | −26% and −5% productivity effects on grain and livestock activities, respectively |

| LPJmL-M3 | 0.5 million workers migrating from FLAB0 to FLAB3, corresponding to LPJmL scenario |

| EPIC-M3 | 1 million workers migrating from FLAB0 to FLAB3, corresponding to EPIC scenario |

| LPJmL-PM3 | LPJmL-P and LPJmL-M (productivity plus migration effects) |

| EPIC-PM3 | EPIC-P and EPIC-M (productivity plus migration effects) |

| EPIC-PM4 | EPIC-P and 1 million labor moving from FLAB0 to FLAB4 |

| EPIC-PM2 | EPIC-P and 1 million labor moving from FLAB0 to FLAB2 |

| EPIC-PM1 | EPIC-P and 1 million labor moving from FLAB0 to FLAB1 |

| EPIC-PL0 | EPIC-P and 0.5 million extra labor force allocated to FLAB0 |

| EPIC-PL3 | EPIC-P and 0.5 million extra labor force allocated to FLAB3 |

| EPIC-PL4 | EPIC-P and 0.5 million extra labor force allocated to FLAB4 |

| EPIC-PL2 | EPIC-P and 0.5 million extra labor force allocated to FLAB2 |

| EPIC-PL1 | EPIC-P and 0.5 million extra labor force allocated to FLAB1 |

| EPIC-PTC | EPIC-P and 10% decline in marketing margins |

| EPIC-PM3TC | EPIC-PM3 and 10% decline in marketing margins |

| Activity | Simulations (% Change) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPJmL-P | EPIC-P | LPJmL-M3 | EPIC-M3 | LPJmL-PM3 | EPIC-PM3 | |

| Grain crops | −9.3 | −24 | −1.7 | −3.4 | −10.8 | −25.6 |

| Cash crops | −3.8 | −13.1 | −1.5 | −3.1 | −5.5 | −15.7 |

| Enset crop | −3.4 | −10.4 | −0.8 | −1.7 | −4.2 | −11.6 |

| Livestock Production | −4.0 | −11.4 | −1.3 | −2.7 | −5.3 | −13.6 |

| Fishing & forestry | −2.5 | −8.1 | −1.1 | −2.2 | −3.6 | −10.0 |

| Mining & quarrying | 0.8 | 2.2 | 1.6 | 3.0 | 2.4 | 5.1 |

| Construction | 0.0 | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Manufacturing | 2.5 | 7.0 | 3.5 | 6.7 | 6.0 | 13.2 |

| Wholesale & retail trade | −1.6 | −5.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −1.6 | −4.8 |

| Hotels & restaurants | −0.8 | −3.2 | 0.5 | 0.8 | −0.4 | −2.6 |

| Transport & comm. | 1.2 | 4.0 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 2.0 | 5.6 |

| Financial intermediaries | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 1.9 |

| Real estate & renting | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Public admin. (general) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Public admin. (agriculture) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Social services | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.7 |

| Other services | 1.1 | 3.3 | 5.1 | 9.8 | 6.2 | 13.5 |

| Total GDP at factor cost | −2.7 | −7.6 | −0.2 | −0.5 | −2.9 | −7.6 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yalew, A.W.; Hirte, G.; Lotze-Campen, H.; Tscharaktschiew, S. Climate Change, Agriculture, and Economic Development in Ethiopia. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3464. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103464

Yalew AW, Hirte G, Lotze-Campen H, Tscharaktschiew S. Climate Change, Agriculture, and Economic Development in Ethiopia. Sustainability. 2018; 10(10):3464. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103464

Chicago/Turabian StyleYalew, Amsalu Woldie, Georg Hirte, Hermann Lotze-Campen, and Stefan Tscharaktschiew. 2018. "Climate Change, Agriculture, and Economic Development in Ethiopia" Sustainability 10, no. 10: 3464. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103464

APA StyleYalew, A. W., Hirte, G., Lotze-Campen, H., & Tscharaktschiew, S. (2018). Climate Change, Agriculture, and Economic Development in Ethiopia. Sustainability, 10(10), 3464. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103464