1. Introduction

The concept of sustainable tourism predicts the direction of both using the resources through conservation and conserving the resources by using them. It is an approach that provides services in terms of supply rather than demand. In this context, it aims to raise the tourism benefits to an optimal level. Sustainable tourism is not purely against growth. This concept willingly advocates that growth is to be bounded by the reasonable limits. Moreover, it deals with the issues of the ecosystem, carrying capacity, and interests of local people. Tourism, as being one of the fastest growing industries of the world, maintains its economic life through depending on natural, historical, and cultural resources which are identified as substantially exhaustible. The tourism industry is liable to the preferences of tourists. The number of arrivals is also dependent on the preservation and use of the above-mentioned resources. For a sustainable development, it is necessary to protect existing natural, cultural, historical, and artificial resources (tourism infrastructure factors) and fundamental ecological processes. Sustainable tourism possesses various principles such as sustainable use of tourism resources, sustainability of diversity, reduction of over-consumption, waste management, tourism planning, integrated work with the local community, supporting local economies, personnel training, consulting to sector stakeholders and local people, responsible tourism market insight, and research responsibility. Sustainable tourism development should be supported by the specific education focused on this topic and the above-listed principles. The qualified human resources trained through sustainable tourism education would play an effective role in the implementation of sustainable tourism policies.

In order to provide a sustainable and effective education, how the students are treated and what the students do is more important than how the teacher behaves and what s/he does in the school environment [

1]. Many researchers studying personality have found that personality traits are an important predictor of academic success as well as other factors, and these personality traits constitute a significant difference in academic performance [

2,

3].Martin et al. found that individual differences in personality play a unique role in educational performance and cognition [

4]. It is very important to determine the personality traits of the students and to prepare the curriculums for sustainable tourism education. Additionally, it is equally significant to determine the teaching methods and to take measures to prevent the practices and methods that might harm the sustainable tourism education.

It is regarded that mobbing possesses the characteristics of being a universal phenomenon as a “business disease” in almost all organizations and cultures [

5], and mobbing cases are increasing day by day in many organizations. Mobbing is not only a psychological or physical harm to employees, but also a managerial problem. It prevents the organization from achieving its organizational and individual goals. Moreover, the organizational climate where the peace within the organization is dominant might be undamaged. In this respect, organizations are to recognize and prevent the mobbing phenomenon and to take the right steps in terms of informing the employees.

Mobbing has been experienced in organizational structures such as educational institutions for various reasons such as disinclining and removing certain individual(s) from the organizational environment, especially students, and it negatively affects the individuals in psychological aspects. In addition, mobbing has remained to be a considerable challenge as being one of the main causes affecting the education and training process in schools. Mobbing cases may lead to negative consequences both from the point of view of students exposed and the school, because the student exposed to mobbing is a member of the school by its very nature. Students who are exposed to mobbing might experience high levels of stress, become psychologically worn out, and experience health problems, such as depressive behaviors.

Mobbing has negative consequences for students and establishments in the organizational level. However, the levels of mobbing perception and the exposure of each student or each individual differ. While some students are more exposed to mobbing, the other ones are less or hardly involved in such cases [

6]. In addition, there might be differences in the level of exposure. This is due to the personality traits of the students.

Mobbing and depression are important factors affecting work-life negatively, as well as being important risk factors in a sustainable education and training process. The subjects of educational organizations are the students. No matter what the reason is, not taking the socio-psychological characteristics of the students and the factors that affect these characteristics into account would directly affect the quality of the educational outcomes. Mobbing and depression, as a mental health problem, arise due to internal and environmental conditions. Both might be seen as the reason for the lack of motivation for undergraduate students causing many problems such as low academic achievement, leaving school, inadequate social and emotional skills, etc. Therefore, the qualifications of the students who are the output of the educational organizations are reduced. Causing damage to the sustainable education process is another potential consequence. Winzer et al. emphasize that interventions for mental illness prevention (methods of coping, techniques of overcoming stress, etc.) are effective in relieving depression, though they lose their effects in the long-term [

7].

Sustainable education is defined as a transformative learning process through new knowledge and thinking styles needed to achieve economic prosperity and create responsible citizenship. This process encompasses the students, teachers, and school systems [

8]. In sustainable tourism education, students need to carry out a transformational learning in which they will adopt the specific characteristics of tourism. In sustainable tourism education, students need to undertake transformational learning in which tourism-specific characteristics would be adopted. Considering the socio-psychological characteristics of the students in sustainable tourism education will increase the quality in the students and educational organizations. In the literature, no study has been conducted to investigate the effect of personality traits on mobbing and depression perceptions of students in sustainable tourism education. This lack of research reveals the originality of the current study. In this study, the relationships between personality traits and mobbing, between personality traits and depression, and between mobbing and depression were investigated. In the literature section (second section), terms and definitions about the concepts of personality, mobbing, and depression, and the relationships among them were explained. In the methodology section (third section), the sample and the research methodology were stated. In the findings section (the fourth section), the relationships among the above-mentioned concepts were examined through the data collected from the students. In the conclusion, discussion and suggestions section (fifth section), the findings of the current study and the similar ones in the literature were compared and suggestions were presented.

3. Methodology

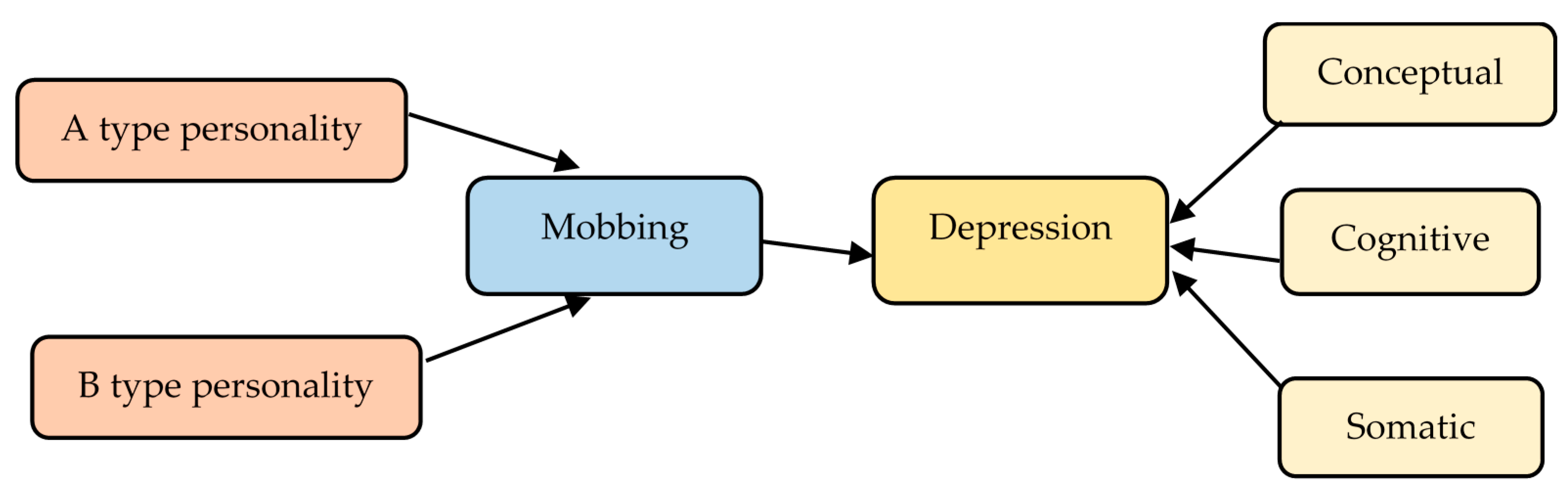

In this study, it was investigated whether belonging to personality type A and personality type B has an effect while being exposed to mobbing behaviors and while being affected by these behaviors. Additionally, levels of depression perceptions (type A-type B) were analyzed whether they indicated any difference. Data were collected from 524 students attending to Akdeniz University Faculty of Tourism. Relationships between personality traits, mobbing, and depression variables were analyzed.

In defining the personality traits, personality inventory developed by Friedman and Rosenman (1959) was used and A or B type personalities identified [

99]. In the determination of mobbing behaviors, mobbing exposure perception levels were measured through a scale prepared by combining “Leymann Inventory of Psychological Terror (LIPT)” developed by Leymann (1996) [

56] and “Negative Acts Questionnaire (NAQ)” developed by Einarsen and Rakness (1997) [

93]. Moreover, “Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)” developed by Beck (1961) [

100] was used to measure the conceptual, cognitive, and somatic components of the students.

3.1. Significance of the Study

The personality traits of people closely influence their behavior patterns, their relationships with others, the way they perceive the environment and the external world, and the psychological situation in which they are. Personality research can contribute to people better understanding themselves, their professional development, and making their social lives more harmonious with the environment. In particular, the identification of the types of personalities and the personal and the environmental qualifications that have the potential to influence these types can contribute to the better understanding of individuals and their successful and peaceful lifespan [

101].

Many factors are assumed to be effective in being the victim of mobbing and being affected by mobbing behavior. Within these factors, the personality traits of the individual are thought to be important in terms of being the target of mobbing behavior and being affected by mobbing behavior. At the same time, having a specific personality affects the individual’s tendency towards depression. Knowing the personality traits will contribute to the development of a certain awareness and understanding of the individual against mobbing and depression which deeply affect the private and social life negatively. As a result of examining the relationship between personality traits and mobbing and depression, it may be possible to manage and control mobbing, and a proactive approach to depression may be revealed.

3.2. Purpose of the Research

The purpose of the study is to determine the personality traits of students attending Akdeniz University Faculty of Tourism and to reveal the relationship between these personality structures, mobbing, and depression. In this study of being exposed to mobbing, being affected by mobbing behavior and depression situations of the students in accordance with the determined personality traits were investigated. Thus, the level of being the victim of mobbing and the level of being affected by mobbing behaviors are revealed. In addition, it was attempted to determine the personality traits of students with high and low depression status.

3.3. Data Collection

The population of the research is composed of 2183 students registered in Akdeniz University Faculty of Tourism in 2017–2018 academic year. In the sample, 524 students were reached with a 95% confidence level through convenience sampling method. Data were collected using the survey technique. The questionnaire created to obtain the data consists of four sections. In the first section, the personal information of the students (gender, family residence, level of income, school preference ranking, satisfaction with the school, satisfaction with the accommodation places) is included. Personality, mobbing, and depression scales are listed in the second, third, and fourth part respectively.

Personality Type Scale: This scale consists of 20 items. It was developed by Fredman and Rosenman. Participants were asked to mark one of the options in the form of “Always”, “Often”, “Sometimes”, “Rarely”, and “Never”. The reliability coefficient calculated for this scale is Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.712. This value indicates that the scale has the relevant reliability score by 0.60 ≤ 0.712 ≤ 0.80 [

102].

Mobbing Scale: Two scales were used to determine mobbing exposure levels. The “Leymann Inventory of Psychological Terror (LIPT) Scale” [

56] covering 45 questions is the first one. The second is the “Negative Acts Questionnaire (NAQ)” developed by Einarsen and Rakness [

93] and Salin [

6] covering 14 questions. By combining these two scales, a scale covering 40 questions was formed. Participants were asked to mark one of the options in the form of “Always”, “Often”, “Sometimes”, “Rarely”, and “Never”.

Depression Scale: Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI) is a self-report scale developed by Beck [

100] to measure emotional, cognitive, somatic, and motivational components. In the validity and reliability study performed by Hisli on 259 university students, the reliability coefficients were found to be r = 0.80 by the item analysis method and by r = 0.74 by the interdivision method. Research results of the studies realized both in Turkey and in the other countries indicated that Beck’s Depression Inventory was tested as a valid and reliable means of measurement [

103]. This scale consist of 21 sets of items, each set is ranked in terms of severity and scored from 0 to 3. Each item has four replying options (0–3) changing conforming to the question. Individual scale items are scored on a 4-point continuum (0 = least, 3 = most), with a total summed score range of 0–63.For instance, in an item, it was listed as from 0 to 3 where “1” means “I do not feel sad” and “4” means “I am so sad and unhappy I cannot stand it”. As dimensions, two items are affective, eleven items are cognitive, two items are behavioral, five items are somatic, and one item is reserved for interpersonal symptoms.

3.4. Research Model

The scales used in this research identified the personality types of the students as A and B, and the levels of mobbing and depression perception were also determined. Thus, the relationships between personality types of students, mobbing exposure, and depression were investigated. In accordance with the hypotheses developed, the research model was presented in

Figure 1.

3.5. Data Analysis

The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was performed to determine whether the data were normally distributed in multivariate analysis, and it was found a normal distribution. Parametric tests (t-test) and descriptive statistics (frequency, percentage, mean, standard deviation), correlation, and regression analysis were selected. Because the data had a normal distribution. Cronbach’s Alpha reliability analysis was used to measure the reliability of the scale used in the study, and confirmatory factor analysis was used to test the construct validity of the depression scale. Statistical analysis packages were used to perform data analysis.

5. Discussion, Conclusions, and Recommendations

In the “Mobbing Information Guide in the Workplace” published by Turkish Republic Ministry of Labor and Social Services (MoLSS) published in 2014, it was mentioned that the effect of mobbing on the victim individual in the workplace can lead to different outcomes due to the stages of psychological harassment and the personality traits of the individual. From the point of the victim, it is generally stated that mobbing causes physical and mental ailments, behavioral disorders, social problems, and economic losses. It is also reported to cause many serious diseases, especially severe depression [

107]. Furlong and Morrison suggested that mobbing in school means “aggressive and criminal behaviors that produce negative consequences on the climate of the school, harm the learning process of the students, and prevent their development” [

108]. These behaviors are stated as direct and indirect threats to the verbal and emotional abuse of the lecturers, the school management and the peer students [

109]. Qualitative research conducted by Sen shows that new and/or successful people in the organization are exposed to mobbing. However, it is stated that people have different thoughts about the behaviors that are evaluated as mobbing and what is perceived as mobbing [

110]. In the current study, it was emphasized that the probability of occurrence of such behaviors and the frequency of these behaviors may be reduced through the recognition and prevention of the main factors that provide the basis for mobbing behaviors.

It is claimed that many factors influence the processes of being exposed to mobbing and being affected by the mobbing behavior in school environment. Personality traits are thought to be important in being the target and in the extent of being affected [

81]. By classifying the personality as type A and type B, researchers shed light on the social and psychological structure of the individual. As a matter of fact, the personality structure possessed by the individual has a great influence on the attitudes and behavior of the individual, his/her relations, positions, and preferences in life. Moreover, decisions made by the individual, one’s harmony with the environment, etc. have considerable impacts as well [

111]. In the study conducted by Kulig et al., it was determined that identifying the personality traits constitutes the first important step in predicting victimization in a school setting [

112]. In this context, it has been proposed to examine different types of personality and their dimensions to determine which features are protective and which of them are risk factors. The qualitative study conducted by Civilidag was realized in order to state the precautions for the prevention of mobbing in educational organizations. Employees and students should be educated about psychological harassment in the workplace, and they should be aware of which behaviors might be regarded as mobbing in the workplace [

113]. Similarly, Tiryaki and Aykac stated that being familiar with the personality types and characteristics would increase the efficiency and communication in the working and school environment [

114].

As a result of current research, the alpha values of the scales used were found to be relevant. A three-dimensional (conceptual, somatic, cognitive) model as proposed by Avşar was formed in the depression scale of the current study [

115]. Analyzes were realized for differences in mobbing and depression perception of the students (type A-type B). There was a significant difference (t = −3.089,

p < 0.05) in mobbing perceptions when compared to personality traits. It was determined that mean of mobbing perception of type A personality traits (

= 1.4501) was higher than that of type B (

= 1.3085). In addition, there was a significant difference (t = −4.033,

p < 0.05) in depression perceptions of students (type A-type B).Similar to mobbing perception, it was determined that the students with type A personality characteristics had a higher average depression perception (

= 1.6007) than type B students (

= 1.4447). Sadeq and Molinari claimed that personality traits are associated with the diagnosis and course of depression in adults [

116]. In this context, it would be useful to evaluate personality traits formally. Similar to the current research, in the study conducted by Aktaş, it was determined that managers with type A personality had a higher level of work stress than those with type B manager [

117]. However, in the study conducted by Okutan and Sututemiz, there was a difference between the personality traits of type A and type B in terms of work-oriented mobbing behaviors. People with type B personality are more likely to be exposed to mobbing behaviors [

118]. Nevertheless, it has been emphasized that workers in this study may not be likely to give honest answers due to concerns about being fired. The possibility of affecting the responses of each other is stated as well.

The relationship between mobbing and depression was examined by the Spearman correlation coefficient technique. It was found that there is a positive correlation between mobbing and depression (r = 0.384,

p < 0.05). As a result of the regression analysis, the mobbing variable with a ß value of 0.327 affected depression positively. The change of 14% in depression was explained by mobbing variable. Besides, mobbing variable affected at most the level of conceptual depression positively and relatively to the other dimensions of depression. As a conclusion, changes of 8%, 5%, and 3% in conceptual, somatic, and cognitive depression, respectively, are explained by the mobbing variable included in the model. When the relationship between mobbing and depression was examined in the study of Akkoca et al., medium and advanced levels of depression were detected in the students who were exposed to mobbing [

119].

Even though the students who are exposed to mobbing have to find ways to deal with their situation and cope with such situations on their own, educational organizations should also make an effort to resolve the problem. It is of utmost importance that universities and academic units are concerned and anxious about the effects of bullying on the welfare and productivity of the faculty [

120]. Educational organizations should be evaluated in terms of the potential events [

121]. It is important to create awareness and to make students and management of the school more be familiar with the administrative and academic mobbing and its consequences so as to prevent mobbing. By doing so, managers and faculty members may be aware of students who are more vulnerable to harassment [

120]. In this context, members of the organization who do not know the ways of the fighting against mobbing should be trained. By this means, it is will be ensured that tutors and department heads have the fundamental knowledge of the issues of witnessing, reporting, and responding to academic mobbing [

122]. Further research should be carried out through the longitudinal research design and specific case studies. In this way, more in-depth information can be obtained about the sophisticated phenomenon of academic mobbing, its consequences on the victim, and effective coping strategies for victims and organizations [

69].

Mobbing and depression should be considered as an organizational and corporate risk factor. In the following process, it is necessary to reduce this risk element to an acceptable level by developing effective controls in the level of management and employees [

123]. Educational organizations play an important role in the training of human resources, being one of the most important capital components in achieving the objectives and targets of enterprises or businesses. Executive Boards of Universities should help develop a cultural and civilized environment. Therefore, they must focus on reducing academic mobbing cases [

70]. Determining the levels of mobbing and depression, which are considered as organizational risk factors in the process of determining the career goals of the students, is of great importance. Since the students are in the educational organizations in the pre-business period, such a focus will provide important contributions in enhancing organizational and individual performance.

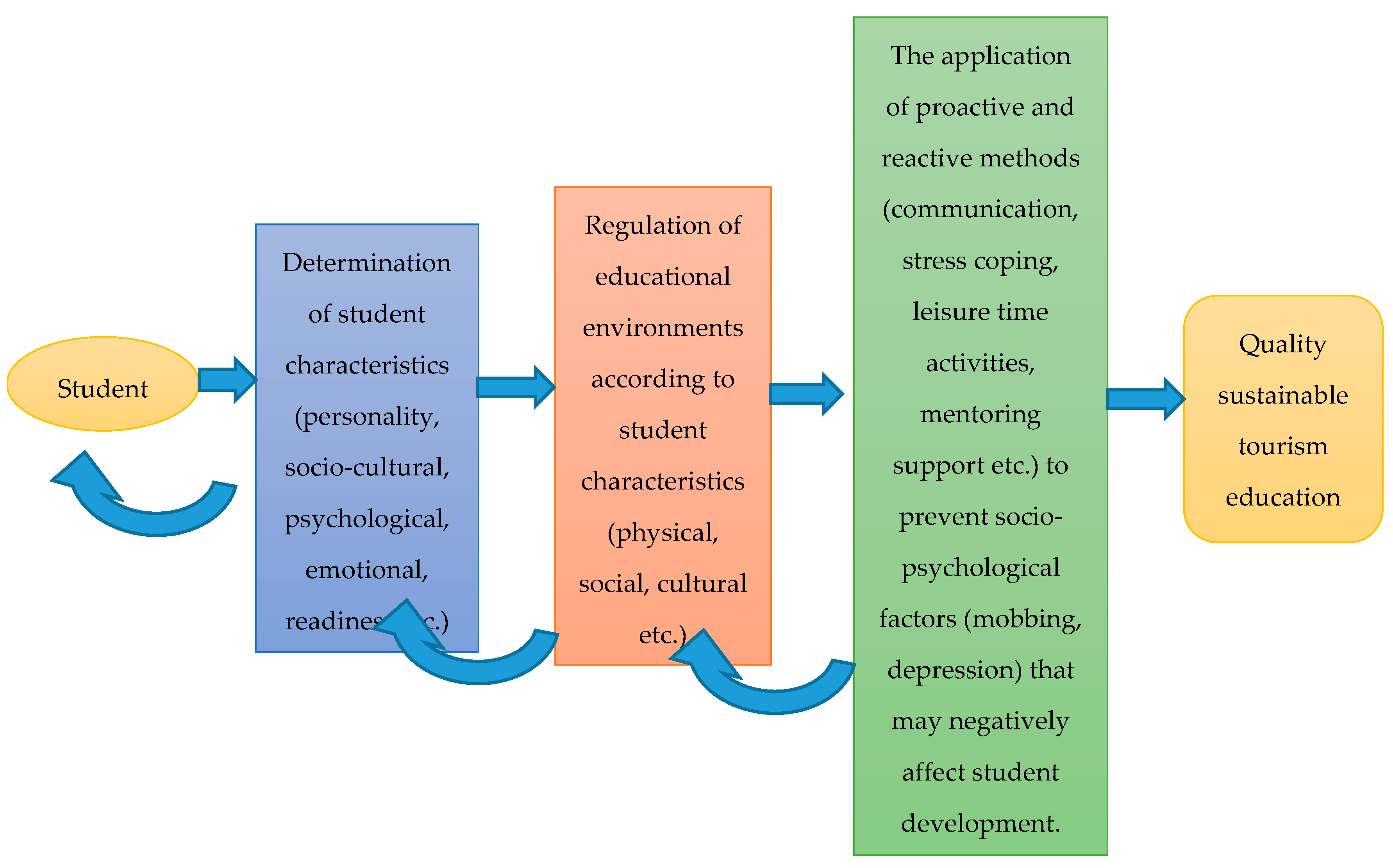

The sustainable tourism education model that is expressed in this study is shown in

Figure 2.

In order for tourism to be sustainable, the expectations of supply (local people, environment, business administration, employees, natural resources, etc.) and demand (tourist) parties must be met at an optimal level. Tourism education needs to be provided within the framework of the consciousness concerning sustainability so as to maintain high quality services provided in supply side. It is important for tourism students and graduates to participate in their education activities in their professional careers throughout their lives, within the context of sustainable tourism and education. As it is known, the diagnosis of the disease is of crucial importance in the prevention and treatment of any disease. Besides, knowing the characteristics of patients affects the success positively during and after the treatment. The same treatment method cannot be applied to each patient for a specific disease, since the patient characteristics are different. Similarly, different educational methods and practices should be developed for the sustainable tourism education according to the individual characteristics of the students. Sustainable education, described by healthy life and disease metaphors, is a proactive process which ensures that educational problems are eliminated before they occur. For this reason, a differentiated tourism education in a suitable physical and social environment according to personal characteristics might have positive outcomes. By this means, measures against mobbing might be taken. As a result, students might be prevented from depression experienced due to mobbing.