Fonseca’s Questionnaire Is a Useful Tool for Carrying Out the Initial Evaluation of Temporomandibular Disorders in Dental Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Populations

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

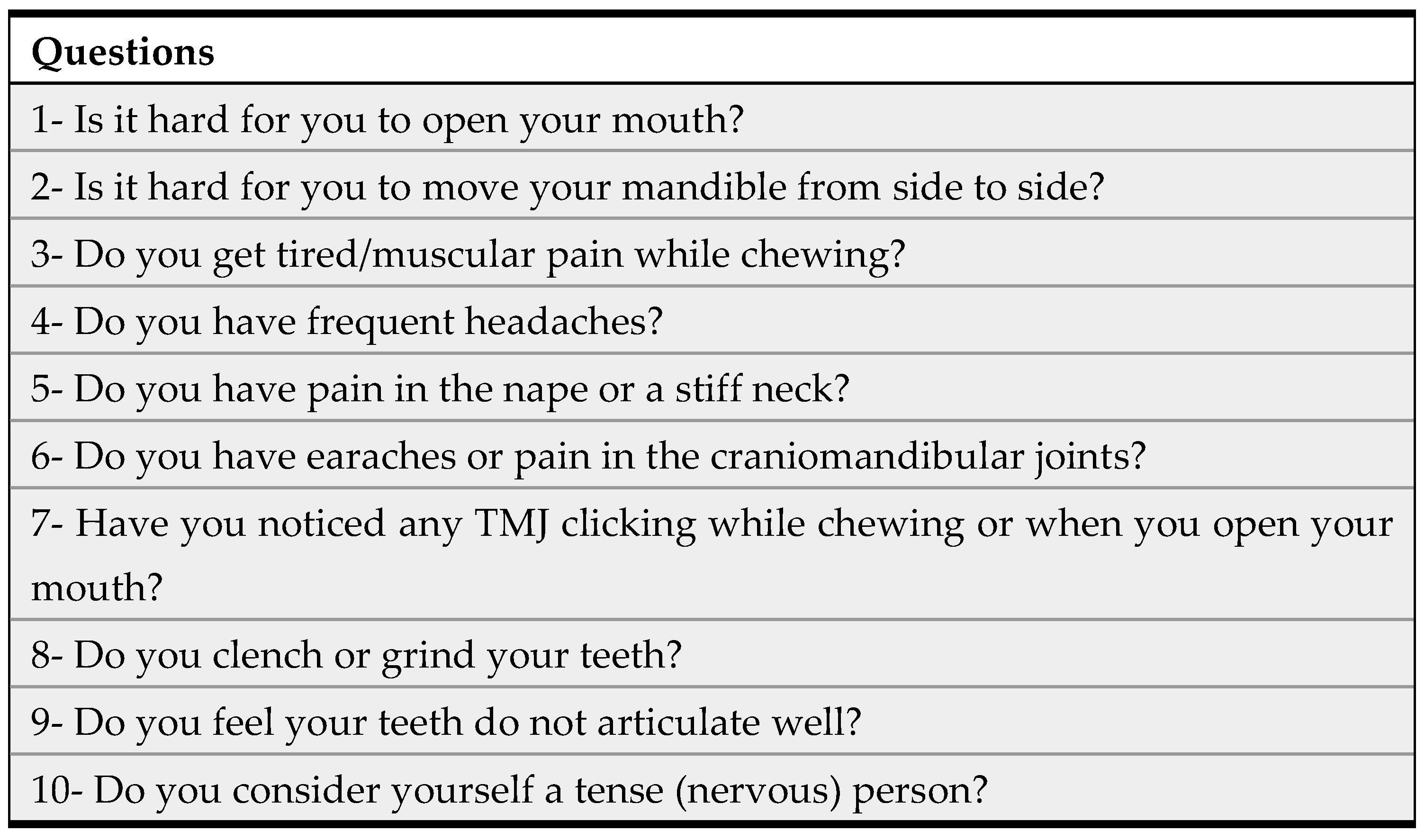

2.4. Fonseca’s Questionnaire

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Limitations

4.2. Clinical Relevance of This Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Name | Gender (M/F) | Age (Years) | Answers to Fonseca’s Questionnaire for Each of the 10 Questions (Items) | Fonseca’s Questionnaire Total Score | Severity Level of TMDs | TMDs Presence (or Not) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | Item 2 | Item 3 | Item 4 | Item 5 | 6 item | Item 7 | Item 8 | Item 9 | Item 10 | ||||||

| M.N | F | 24–26 | No | No | Sometimes | Yes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | No | No | Sometimes | 40 | Mild | No |

| A.P | F | 20–23 | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 60 | Moderate | Yes |

| G.N | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | Yes | 15 | Not present | No |

| K.A | F | 24–26 | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | 50 | Moderate | Yes |

| F.B | M | 27–30 | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | 50 | Moderate | Yes |

| R.L | M | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | Yes | No | Sometimes | 20 | Mild | No |

| F.F | F | 24–26 | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | 70 | Severe | Yes |

| R.T | M | 24–26 | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | 20 | Mild | No |

| A.F | F | 20–23 | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | 55 | Moderate | Yes |

| A.L | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Sometimes | Yes | No | Sometimes | 40 | Mild | No |

| M.F | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | 5 | Not present | No |

| S.B | F | 27–30 | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | Sometimes | No | Yes | No | Yes | 55 | Moderate | Yes |

| S.W | M | 24–26 | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | Yes | 20 | Mild | No |

| L.S | F | 24–26 | No | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | No | No | Sometimes | No | Yes | Yes | 35 | Mild | No |

| M.T | F | 24–26 | No | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | No | 50 | Moderate | Yes |

| G.P | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | Yes | Sometimes | No | No | 20 | Mild | No |

| F.R | F | 24–26 | Sometimes | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | Yes | Sometimes | No | Yes | 35 | Mild | No |

| V.P | M | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | 10 | Not present | No |

| L.G | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | Yes | No | Yes | 35 | Mild | No |

| A.G | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | No | 10 | Not present | No |

| G.M | F | 20–23 | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | Yes | 35 | Mild | No |

| F.DP | M | 27–30 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | 5 | Not present | No |

| M.T | M | 20–23 | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Sometimes | 35 | Mild | No |

| F.A | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | No | Sometimes | 40 | Mild | No |

| P.L | M | 24–26 | No | No | No | Sometimes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | 20 | Mild | No |

| N.P | F | 24–26 | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | 40 | Mild | No |

| N.PL | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | Sometimes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | 35 | Mild | No |

| M.T | F | 27–30 | No | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | 30 | Mild | No |

| E.N | M | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | 10 | Not present | No |

| F.G | F | 27–30 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | 10 | Not present | No |

| A.B | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Sometimes | 15 | Not present | No |

| F.P | M | 27–30 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | 35 | Mild | No |

| P.P | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | 10 | Not present | No |

| E.L | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Sometimes | 45 | Moderate | Yes |

| M.L | F | 24–26 | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 75 | Severe | Yes |

| A.O | F | 27–30 | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 60 | Moderate | Yes |

| M.M | F | 24–26 | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Sometimes | 55 | Moderate | Yes |

| A.B | F | 20–23 | Sometimes | No | No | Sometimes | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 55 | Moderate | Yes |

| G.A | F | 20–23 | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | No | Sometimes | Yes | Sometimes | Sometimes | 45 | Moderate | Yes |

| T.M | F | 24–26 | No | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | 45 | Moderate | Yes |

| M.M | F | 24–26 | No | No | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Yes | 50 | Moderate | Yes |

| D.GP | F | 24–26 | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | No | 30 | Mild | No |

| M.D | M | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Sometimes | No | Yes | 25 | Mild | No |

| S.C | F | 24–26 | No | No | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | 60 | Moderate | Yes |

| A.P | F | 20–23 | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | Yes | 20 | Mild | No |

| V.O | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | Yes | Sometimes | No | No | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | 25 | Mild | No |

| M.F | F | 20–23 | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Sometimes | 20 | Mild | No |

| C.F | F | 20–23 | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | 40 | Mild | No |

| M.M | M | 20–23 | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 40 | Mild | No |

| R.F | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Sometimes | No | Yes | 55 | Moderate | Yes |

| A.A | M | 27–30 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | 0 | Not present | No |

| F.M | F | 24–26 | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 55 | Moderate | Yes |

| S.C | F | 20–23 | Sometimes | No | Yes | Sometimes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 55 | Moderate | Yes |

| S.R | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Sometimes | 15 | Not present | No |

| M.P | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 45 | Moderate | Yes |

| M.R | F | 24–26 | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | 45 | Moderate | Yes |

| S.A | M | 24–26 | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | 30 | Mild | No |

| E.P | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | Yes | 15 | Not present | No |

| M.B | F | 20–23 | No | No | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | 40 | Mild | No |

| M.E | F | 27–30 | No | No | No | Sometimes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | 35 | Mild | No |

| G.V | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Sometimes | 15 | Not present | No |

| S.B | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | Yes | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | 40 | Mild | No |

| G.Z | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | Sometimes | 25 | Mild | No |

| F.T | F | 24–26 | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 55 | Moderate | Yes |

| V.V | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | 15 | Not present | No |

| E.V | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | 5 | Not present | No |

| G.C | F | 24–26 | No | Yes | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | 55 | Moderate | Yes |

| S.C | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 30 | Mild | No |

| M.AM | M | 24–26 | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | 35 | Mild | No |

| B.A | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 40 | Mild | No |

| L.G | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | Yes | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | 25 | Mild | No |

| S.B | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | 5 | Not present | No |

| T.C | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Yes | 20 | Mild | No |

| D.V | M | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | 20 | Mild | No |

| D.T | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | Yes | No | No | Sometimes | 20 | Mild | No |

| E.R | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | Sometimes | 10 | Not present | No |

| P.P | F | 27–30 | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Sometimes | 25 | Mild | No |

| V.A | F | 24–26 | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Yes | 50 | Moderate | Yes |

| P.B | F | 27–30 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Sometimes | Sometimes | 20 | Mild | No |

| L.B | M | 24–26 | No | No | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | No | No | Sometimes | 20 | Mild | No |

| E.N | F | 27–30 | Sometimes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | No | 30 | Mild | No |

| G.P | F | 24–26 | No | Yes | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 55 | Moderate | Yes |

| C.N | M | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | 30 | Mild | No |

| L.C | M | 24–26 | No | Yes | Yes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 65 | Moderate | Yes |

| M.L | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | Sometimes | 35 | Mild | No |

| P.V | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 30 | Mild | No |

| R.M | M | 27–30 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | 10 | Not present | No |

| D.B | F | 20–23 | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 50 | Moderate | Yes |

| S.L | F | 24–26 | Sometimes | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 55 | Moderate | Yes |

| C.C | F | 20–23 | Sometimes | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | Sometimes | 15 | Not present | No |

| G.R | M | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | 5 | Not present | No |

| F.R | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | No | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | 20 | Mild | No |

| C.C | M | 24–26 | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | No | No | Sometimes | 25 | Mild | No |

| M.T | F | 20–23 | Sometimes | No | No | Yes | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | No | Yes | No | 35 | Mild | No |

| F.M | F | 24–26 | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 55 | Moderate | Yes |

| S.C | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | 40 | Mild | No |

| D.T | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | 5 | Not present | No |

| G.L | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | 20 | Mild | No |

| L.T | F | 24–26 | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 85 | Severe | Yes |

| A.P | M | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | Yes | Sometimes | 20 | Mild | No |

| VN.T | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | 20 | Mild | No |

| F.O | F | 24–26 | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Yes | 40 | Mild | No |

| A.MR | M | 24–26 | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | Yes | Sometimes | 25 | Mild | No |

| S.B | M | 27–30 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | 20 | Mild | No |

| A.T | M | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | 20 | Mild | No |

| A.M | M | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | Yes | Sometimes | Sometimes | 25 | Mild | No |

| S.L | M | 27–30 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | 25 | Mild | No |

| R.D | M | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | Sometimes | Yes | 20 | Mild | No |

| T.A | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | Yes | Sometimes | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | 20 | Mild | No |

| M.P | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | No | No | Yes | Sometimes | 25 | Mild | No |

| P.G | F | 24–26 | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | No | 35 | Mild | No |

| M.V | F | 24–26 | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | 30 | Mild | No |

| A.A | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | 15 | Not present | No |

| B.L | M | 20–23 | No | No | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | No | Yes | No | No | No | 20 | Mild | No |

| G.G | M | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 40 | Mild | No |

| N.F | M | 27–30 | No | No | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 75 | Severe | Yes |

| A.B | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | Sometimes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | 25 | Mild | No |

| F.D | F | 24–26 | Yes | Yes | No | Sometimes | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | Sometimes | 70 | Severe | Yes |

| F.G | F | 24–26 | No | No | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | Sometimes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 60 | Moderate | Yes |

| A.R | F | 20–23 | Sometimes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Sometimes | 20 | Mild | No |

| I.F | F | 20–23 | Yes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 80 | Severe | Yes |

| O.B | F | 27–30 | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 65 | Moderate | Yes |

| M.C | M | 24–26 | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 45 | Moderate | Yes |

| O.D | M | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | 5 | Not present | No |

| P.A | M | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | 20 | Mild | No |

| R.A | F | 24–26 | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | Sometimes | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | 35 | Mild | No |

| B.G | F | 24–26 | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | Sometimes | No | Yes | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | 75 | Severe | Yes |

| M.B | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 40 | Mild | No |

| G.R | F | 24–26 | Sometimes | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | 30 | Mild | No |

| A.L | F | 20–23 | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Sometimes | Sometimes | 25 | Mild | No |

| MG.D | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | 10 | Not present | No |

| S.B | M | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | 0 | Not present | No |

| J.P | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | Yes | 20 | Mild | No |

| MK.L | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Yes | 20 | Mild | No |

| A.A | F | 24–26 | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | Yes | Sometimes | 30 | Mild | No |

| F.C | F | 24–26 | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Yes | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | 40 | Mild | No |

| V.N | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Sometimes | Yes | No | Yes | 35 | Mild | No |

| L.V | M | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | 10 | Not present | No |

| S.B | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | 25 | Mild | No |

| A.DL | M | 20–23 | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Sometimes | No | No | Yes | 35 | Mild | No |

| G.A | M | 20–23 | Sometimes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Sometimes | 40 | Mild | No |

| R.B | M | 20–23 | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | 40 | Mild | No |

| A.B | F | 24–26 | No | No | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | 40 | Mild | No |

| D.Z | M | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | 0 | Not present | No |

| C.G | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Sometimes | 25 | Mild | No |

| M.T | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 40 | Mild | No |

| R.C | F | 20–23 | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | No | Sometimes | 35 | Mild | No |

| G.O | M | 27–30 | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | 25 | Mild | No |

| B.C | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | Sometimes | Yes | 15 | Not present | No |

| P.R | M | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | 5 | Not present | No |

| F.G | M | 24–26 | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | 25 | Mild | No |

| G.S | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | 20 | Mild | No |

| F.B | F | 27–30 | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | 35 | Mild | No |

| M.L | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | 5 | Not present | No |

| S.W | M | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | 20 | Mild | No |

| S.S | F | 20–23 | Sometimes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 55 | Moderate | Yes |

| P.B | M | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | 10 | Not present | No |

| AM.A | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | No | 15 | Not present | No |

| S.B | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Sometimes | 40 | Mild | No |

| B.L | M | 27–30 | Sometimes | No | Yes | No | Sometimes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Sometimes | 45 | Moderate | Yes |

| R.V | F | 24–26 | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | No | Sometimes | 30 | Mild | No |

| C.B | F | 27–30 | No | No | Sometimes | Yes | Sometimes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | 40 | Mild | No |

| A.B | F | 20–23 | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 35 | Mild | No |

| P.C | F | 20–23 | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | 45 | Moderate | Yes |

| P.B | F | 27–30 | No | No | Yes | No | No | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 50 | Moderate | Yes |

| A.A | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | 5 | Not present | No |

| A.B | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | 10 | Not present | No |

| L.S | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | 0 | Not present | No |

| L.C | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | 10 | Not present | No |

| P.B | F | 24–26 | No | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 65 | Moderate | Yes |

| E.R | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | 50 | Moderate | Yes |

| L.B | F | 24–26 | Sometimes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | No | Sometimes | 40 | Mild | No |

| V.A | M | 27–30 | Sometimes | No | Yes | Sometimes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Sometimes | 45 | Moderate | Yes |

| F.B | F | 27–30 | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | 50 | Moderate | Yes |

| F.F | M | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Sometimes | 20 | Mild | No |

| A.M | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | 20 | Mild | No |

| P.V | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | 30 | Mild | No |

| M.V | F | 24–26 | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | Yes | 20 | Mild | No |

| P.S | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | 0 | Not present | No |

| N.S | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Sometimes | No | No | 15 | Not present | No |

| L.R | F | 27–30 | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | No | No | Sometimes | 15 | Not present | No |

| E.Z | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | 35 | Mild | No |

| F.R | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | Yes | No | 15 | Not present | No |

| S.B | F | 27–30 | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | Sometimes | Yes | Sometimes | 25 | Mild | No |

| B.E | F | 27–30 | Sometimes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 35 | Mild | No |

| B.G | M | 24–26 | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 35 | Mild | No |

| T.F | M | 27–30 | No | Yes | No | Sometimes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Sometimes | 40 | Mild | No |

| AR.G | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | 5 | Not present | No |

| M.B | M | 27–30 | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | 25 | Mild | No |

| A.F | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | 5 | Not present | No |

| D.H | F | 20–23 | Sometimes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 65 | Moderate | Yes |

| E.P | M | 24–26 | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Yes | 30 | Mild | No |

| F.P | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 30 | Mild | No |

| M.L | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | 5 | Not present | No |

| S.C | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | 5 | Not present | No |

| R.B | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | 20 | Mild | No |

| A.P | M | 24–26 | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Sometimes | 35 | Mild | No |

| S.A | M | 24–26 | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | 40 | Mild | No |

| E.R | M | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | 10 | Not present | No |

| F.P | M | 24–26 | No | Yes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | 55 | Moderate | Yes |

| M.M | F | 27–30 | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | 40 | Mild | No |

| C.M | M | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | 10 | Not present | No |

| A.B | M | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | No | No | Yes | 30 | Mild | No |

| G.I | M | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | 15 | Not present | No |

| S.P | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | 20 | Mild | No |

| E.P | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | 20 | Mild | No |

| I.U | F | 24–26 | No | No | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | 30 | Mild | No |

| D.A | F | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 30 | Mild | No |

| P.A | M | 20–23 | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Sometimes | 45 | Moderate | Yes |

| S.S | M | 24–26 | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | Yes | Sometimes | 30 | Mild | No |

| N.M | F | 20–23 | No | No | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 45 | Moderate | Yes |

| D.V | F | 20–23 | No | No | Sometimes | No | Yes | No | No | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | 40 | Mild | No |

| S.B | M | 20–23 | No | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 50 | Moderate | Yes |

| O.D | F | 24–26 | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | 45 | Moderate | Yes |

| N.V | M | 20–23 | No | No | No | Sometimes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | 20 | Mild | No |

| R.M | M | 24–26 | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | Sometimes | 15 | Mild | No |

| M.F | M | 20–23 | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Sometimes | No | Yes | 35 | Mild | No |

| G.M | F | 20–23 | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | Yes | Yes | 35 | Mild | No |

| A.R | F | 27–30 | No | No | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | Sometimes | 55 | Moderate | Yes |

| F.R | M | 27–30 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | 10 | Not present | No |

| M.R | M | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Sometimes | 25 | Mild | No |

| E.R | M | 27–30 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | 10 | Not present | No |

| E.C | M | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | 10 | Not present | No |

| M.S | M | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | 0 | Not present | No |

| S.P | F | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | Yes | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | 25 | Mild | No |

| GP.M | F | 20–23 | No | Sometimes | No | No | Sometimes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 50 | Moderate | Yes |

| G.R | F | 24–26 | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Sometimes | 25 | Mild | No |

| E.V | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 40 | Mild | No | |

| L.P | 20–23 | No | No | No | Sometimes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | 25 | Mild | No | |

| L.V | 27–30 | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | 20 | Mild | No | |

| S.T | 24–26 | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | Sometimes | No | Yes | 60 | Moderate | Yes | |

| C.B | 20–23 | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | 30 | Mild | No | |

| M.P | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Sometimes | 30 | Mild | No | |

| G.T | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | 5 | Not present | No | |

| G.C | 24–26 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | 20 | Mild | No | |

| M.M | 27–30 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | 10 | Mild | No | |

| L.B | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | 20 | Mild | No | |

| M.B | 20–23 | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 50 | Moderate | Yes | |

| V.R | 24–26 | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | 60 | Moderate | Yes | |

| C.M | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 40 | Mild | No | |

| M.S | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | 10 | Not present | No | |

| W.B | 20–23 | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | 40 | Mild | No | |

| A.F | 20–23 | No | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | 15 | Not present | No | |

| L.B | 20–23 | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Sometimes | 30 | Mild | No | |

| R.S | 20–23 | No | No | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | No | No | No | Sometimes | 15 | Not present | No | |

| P.Z | 27–30 | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | No | Sometimes | No | No | Sometimes | Yes | 35 | Mild | No | |

| M.L | 20–23 | Sometimes | Sometimes | No | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | 70 | Severe | Yes | |

| AM.R | 20–23 | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 65 | Moderate | Yes | |

| V.B | 24–26 | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | 40 | Mild | No | |

| ME.P | 24–26 | No | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | No | No | Yes | 50 | Moderate | Yes | |

References

- Valesan, L.F.; Da-Cas, C.D.; Réus, J.C.; Denardin, A.C.S.; Garanhani, R.R.; Bonotto, D.; Januzzi, E.; de Souza, B.D.M. Prevalence of temporomandibular joint disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2021, 25, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffman, E.; Ohrbach, R.; Truelove, E.; Look, J.; Anderson, G.; Goulet, J.-P.; Odont, T.L.; Odont, P.S.; Gonzalez, Y.; Lobbezoo, F.; et al. International RDC/TMD Consortium Network, International association for Dental Research; Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group, International Association for the Study of Pain. Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: Recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network* and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group. J. Oral. Facial. Pain Headache 2014, 28, 6–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ohrbach, R.; Dworkin, S.F. The Evolution of TMD Diagnosis: Past, Present, Future. J. Dent. Res. 2016, 95, 1093–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.T.S.; Leung, Y.Y. Temporomandibular Disorders: Current Concepts and Controversies in Diagnosis and Management. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrillo, M.; Marotta, N.; Viola, P.; Chiarella, G.; Fortunato, L.; Ammendolia, A.; Giudice, A.; de Sire, A. Efficacy of rehabilitative therapies on otologic symptoms in patients with temporomandibular disorders: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. J. Oral Rehabil. 2024, 51, 1621–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos Proença, J.; Baad-Hansen, L.; do Vale Braido, G.V.; Campi, L.B.; de Godoi Gonçalves, D.A. Clinical features of chronic primary pain in individuals presenting painful temporomandibular disorder and comorbidities. J. Oral Rehabil. 2024, 51, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, D.; Lombardo, L.; Siciliani, G. Temporomandibular disorders and dental occlusion. A systematic review of association studies: End of an era? J. Oral Rehabil. 2017, 44, 908–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisnoiu, A.M.; Picos, A.M.; Popa, S.; Chisnoiu, P.D.; Lascu, L.; Picos, A.; Chisnoiu, R. Factors involved in the etiology of temporomandibular disorders—A literature review. Clujul Med. 2015, 88, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesch, D.; Bernhardt, O.; Mack, F.; John, U.; Kocher, T.; Alte, D. Association of malocclusion and functional occlusion with subjective symptoms of TMD in adults: Results of the Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP). Angle Orthod. 2005, 75, 183–190. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Steinkeler, A. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of temporomandibular disorders. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 57, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaves, P.J.; de Oliveira, F.E.M.; Damázio, L.C.M. Incidence of postural changes and temporomandibular disorders in students. Acta Ortop. Bras. 2017, 25, 162–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alrizqi, A.H.; Aleissa, B.M. Prevalence of Temporomandibular Disorders Between 2015–2021: A Literature Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e37028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.J.; Lamster, I.B.; Greenspan, J.S.; Pitts, N.B.; Scully, C.; Warnakulasuriya, S. Global burden of oral diseases: Emerging concepts, management and interplay with systemic health. Oral Dis. 2016, 22, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges, R.E.A.; Mendonça, L.D.R.A.; Dos Santos Calderon, P. Diagnostic and screening inventories for temporomandibular disorders: A systematic review. Cranio 2024, 42, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, N.; van Wijk, A.; Visscher, C.M. Psychosocial oral health-related quality of life impact: A systematic review. J. Oral Rehabil. 2021, 48, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cianetti, S.; Valenti, C.; Orso, M.; Lomurno, G.; Nardone, M.; Lomurno, A.P.; Pagano, S.; Lombardo, G. Systematic Review of the Literature on Dental Caries and Periodontal Disease in Socio-Economically Disadvantaged Individuals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paglia, L.; Gallus, S.; de Giorgio, S.; Cianetti, S.; Lupatelli, E.; Lombardo, G.; Montedori, A.; Eusebi, P.; Gatto, R.; Caruso, S. Reliability and validity of the Italian versions of the Children’s Fear Survey Schedule—Dental Subscale and the Modified Child Dental Anxiety Scale. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2017, 18, 305–312. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, M.C.; Ramos-Jorge, M.L.; Marques, L.S.; Ferreira, F.O. Dental caries and quality of life of preschool children: Discriminant validity of the ECOHIS. Braz. Oral Res. 2017, 31, e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kanatas, A.N.; Rogers, S.N. A systematic review of patient self-completed questionnaires suitable for oral and maxillofacial surgery. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2010, 48, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobilio, N.; Casetta, I.; Cesnik, E.; Catapano, S. Prevalence of self-reported symptoms related to temporomandibular disorders in an Italian population. J. Oral Rehabil. 2011, 38, 884–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paduano, S.; Bucci, R.; Rongo, R.; Silva, R.; Michelotti, A. Prevalence of temporomandibular disorders and oral parafunctions in adolescents from public schools in Southern Italy. Cranio 2020, 38, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Câmara-Souza, M.B.; Bracci, A.; Colonna, A.; Ferrari, M.; Rodrigues Garcia, R.C.M.; Manfredini, D. Ecological Momentary Assessment of Awake Bruxism Frequency in Patients with Different Temporomandibular Disorders. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, D.; Lombardo, L.; Siciliani, G. Dental Angle class asymmetry and temporomandibular disorders. J. Orofac. Orthop. 2017, 78, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, D.; Winocur, E.; Guarda-Nardini, L.; Lobbezoo, F. Self-reported bruxism and temporomandibular disorders: Findings from two specialised centres. J. Oral. Rehabil. 2012, 39, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, D.; Arveda, N.; Guarda-Nardini, L.; Segù, M.; Collesano, V. Distribution of diagnoses in a population of patients with temporomandibular disorders. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2012, 114, e35–e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, D.; Bandettini di Poggio, A.; Cantini, E.; Dell’Osso, L.; Bosco, M. Mood and anxiety psychopathology and temporomandibular disorder: A spectrum approach. J. Oral Rehabil. 2004, 31, 933–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarda-Nardini, L.; Pavan, C.; Arveda, N.; Ferronato, G.; Manfredini, D. Psychometric features of temporomandibular disorders patients in relation to pain diffusion, location, intensity and duration. J. Oral Rehabil. 2012, 39, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canales, G.T.; Guarda-Nardini, L.; Rizzatti-Barbosa, C.M.; Conti, P.C.R.; Manfredini, D. Distribution of depression, somatization and pain-related impairment in patients with chronic temporomandibular disorders. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2019, 27, e20180210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaynak, B.A.; Taş, S.; Salkın, Y. The accuracy and reliability of the Turkish version of the Fonseca anamnestic index in temporomandibular disorders. Cranio 2023, 41, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, K.; Vitti, M.; de Oliveira, A.S.; Chaves, T.C.; Semprini, M.; Siéssere, S.; Hallak, J.E.C.; Regalo, S.C.H. Use of the Fonseca’s questionnaire to assess the prevalence and severity of temporomandibular disorders in brazilian dental undergraduates. Braz. Dent. J. 2007, 18, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, A.S.; Dias, E.M.; Contato, R.G.; Berzin, F. Prevalence study of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorder in Brazilian college students. Braz. Oral Res. 2006, 20, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, A.U.; Zhang, M.J.; Lei, J.; Fu, K.Y. Diagnostic accuracy of the short-form Fonseca Anamnestic Index in relation to the Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 128, 977–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarasca-Berrocal, E.; Huamani-Echaccaya, J.; Tolmos-Valdivia, R.; Tolmos-Regal, L.; López-Gurreonero, C.; Cervantes-Ganoza, L.A.; Cayo-Rojas, C.F. Predictability and Accuracy of the Short-Form Fonseca Anamnestic Index in Relation to the Modified Helkimo Index for the Diagnosis of Temporomandibular Disorders: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2022, 12, 178–188. [Google Scholar]

- Topuz, M.F.; Oghan, F.; Ceyhan, A.; Ozkan, Y.; Erdogan, O.; Musmul, A.; Kutuk, S.G. Assessment of the severity of temporomandibular disorders in females: Validity and reliability of the Fonseca anamnestic index. Cranio 2023, 41, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagalaz-Anula, N.; Sánchez-Torrelo, C.M.; Acebal-Blanco, F.; Alonso-Royo, R.; Ibáñez-Vera, A.J.; Obrero-Gaitán, E.; Rodríguez-Almagro, D.; Lomas-Vega, R. The Short Form of the Fonseca Anamnestic Index for the Screening of Temporomandibular Disorders: Validity and Reliability in a Spanish-Speaking Population. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Torrelo, C.M.; Zagalaz-Anula, N.; Alonso-Royo, R.; Ibáñez-Vera, A.J.; López Collantes, J.; Rodríguez-Almagro, D.; Obrero-Gaitán, E.; Lomas-Vega, R. Transcultural Adaptation and Validation of the Fonseca Anamnestic Index in a Spanish Population with Temporomandibular Disorders. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilaqua-Grossi, D.; Chaves, T.C.; de Oliveira, A.S.; Monteiro-Pedro, V. Anamnestic index severity and signs and symptoms of TMD. Cranio 2006, 24, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, A.U.; Zhang, M.J.; Lei, J.; Fu, K.Y. Accuracy of the Fonseca Anamnestic Index for identifying pain-related and/or intra-articular Temporomandibular Disorders. Cranio 2024, 14, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasiak, G.; Maracci, L.M.; de Oliveira Chami, V. TMD diagnosis: Sensitivity and specificity of the Fonseca Anamnestic Index. Cranio 2023, 41, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, J.A.; Carrascosa, A.C.; Bonafé, F.S.; Maroco, J. Severity of temporomandibular disorders in women: Validity and reliability of the Fonseca Anamnestic Index. Braz. Oral Res. 2014, 28, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Moraissi, E.A.; Conti, P.C.R.; Alyahya, A.; Alkebsi, K.; Elsharkawy, A.; Christidis, N. The hierarchy of different treatments for myogenous temporomandibular disorders: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 26, 519–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minervini, G.; Franco, R.; Marrapodi, M.M.; Fiorillo, L.; Cervino, G.; Cicciù, M. Economic inequalities and temporomandibular disorders: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Oral Rehabil. 2023, 50, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monarchi, G.; Consorti, G.; Balercia, A.; Pau, A.; Balercia, P.; Di Benedetto, G. Influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on temporo-mandibular joint disorders. Dental Cadmos. 2024, 92, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, G.E.; Colquhoun, L.; Lancastle, D.; Lewis, N.; Tyson, P.J. Review: Physical activity interventions for the mental health and well-being of adolescents—A systematic review. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2021, 26, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minervini, G.; Franco, R.; Marrapodi, M.M.; Crimi, S.; Badnjević, A.; Cervino, G.; Bianchi, A.; Cicciù, M. Correlation between Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD) and Posture Evaluated trough the Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD): A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.; Eley, K.A.; Cascarini, L.; Watt-Smith, S.; Larkin, M.; Lloyd, T.; Maddocks, C.; McLaren, E.; Stovell, R.; McMillan, R. Temporomandibular disorders-review of evidence-based management and a proposed multidisciplinary care pathway. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2023, 136, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, M.; Puleio, F.; Lo Giudice, R.; Alibrandi, A.; Campione, I. The professional interactions between speechlanguage therapist and dentist. Explor. Med. 2024, 5, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauer, R.L.; Semidey, M.J. Diagnosis and treatment of temporomandibular disorders. Am. Fam. Physician 2015, 91, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| TMD Severity | F | M | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absent/Mild | 71.43% | 88.00% | 76.40% |

| Moderate/Severe | 28.57% | 12.00% | 23.60% |

| Total | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

| Age of Participants | Absent/Mild | Moderate/Severe | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20–23 | 37.17% | 32.20% | 36.00% |

| 24–26 | 49.21% | 50.85% | 49.60% |

| 27–30 | 13.61% | 16.95% | 14.40% |

| Total | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

| TMD Severity | Employed | Unemployed | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absent | 15 | 40 | 55 |

| Mild | 47 | 89 | 136 |

| Moderate | 15 | 36 | 51 |

| Severe | 3 | 5 | 8 |

| Total | 80 | 170 | 250 |

| Regular Physical Activity | Absent/Mild | Moderate/Severe | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | 36.65% | 38.98% | 37.20% |

| Yes | 63.35% | 61.02% | 62.80% |

| Total | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mitro, V.; Caso, A.R.; Sacchi, F.; Gilli, M.; Lombardo, G.; Monarchi, G.; Pagano, S.; Tullio, A. Fonseca’s Questionnaire Is a Useful Tool for Carrying Out the Initial Evaluation of Temporomandibular Disorders in Dental Students. Clin. Pract. 2024, 14, 1650-1668. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract14050132

Mitro V, Caso AR, Sacchi F, Gilli M, Lombardo G, Monarchi G, Pagano S, Tullio A. Fonseca’s Questionnaire Is a Useful Tool for Carrying Out the Initial Evaluation of Temporomandibular Disorders in Dental Students. Clinics and Practice. 2024; 14(5):1650-1668. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract14050132

Chicago/Turabian StyleMitro, Valeria, Angela Rosa Caso, Federica Sacchi, Massimiliano Gilli, Guido Lombardo, Gabriele Monarchi, Stefano Pagano, and Antonio Tullio. 2024. "Fonseca’s Questionnaire Is a Useful Tool for Carrying Out the Initial Evaluation of Temporomandibular Disorders in Dental Students" Clinics and Practice 14, no. 5: 1650-1668. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract14050132

APA StyleMitro, V., Caso, A. R., Sacchi, F., Gilli, M., Lombardo, G., Monarchi, G., Pagano, S., & Tullio, A. (2024). Fonseca’s Questionnaire Is a Useful Tool for Carrying Out the Initial Evaluation of Temporomandibular Disorders in Dental Students. Clinics and Practice, 14(5), 1650-1668. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract14050132