Estimation of Serum Calcium on the Severity and Mortality in COVID-19 Infections in Sulaymaniyah City, Kurdistan Region of Iraq: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Laboratory Testing Determination of Serum (Calcium)

3. Results

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aziz, P.Y.; Hadi, J.M.; Aram, M.S.; Aziz, S.B.; Rahman, H.S.; Ahmed, H.A.; Abdulla, M.A.; Ali, S.M.A. The strategy for controlling COVID-19 in Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG)/Iraq: Identification, epidemiology, transmission, treatment, and recovery. Int. J. Surg. Open 2020, 25, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.; Ahmed, Z.A.; Siddiqui, I.; Rashid, N.H.; Mansoor, M.; Jafri, L. Evaluation of serum ferritin for prediction of severity and mortality in COVID-19-A cross sectional study. Ann. Med. Surg. 2021, 63, 102163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafeez, A.; Ahmad, S.; Siddqui, S.A.; Ahmad, M.; Mishra, S. A review of COVID-19 (Coronavirus Disease-2019) diagnosis, treatments and prevention. EJMO 2020, 4, 116–125. [Google Scholar]

- Harapan, H.; Itoh, N.; Yufika, A.; Winardi, W.; Keam, S.; Te, H.; Megawati, D.; Hayati, Z.; Wagner, A.L.; Mudatsir, M. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A literature review. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Wu, Z.; Li, J.W.; Zhao, H.; Wang, G.Q. Cytokine Release Syndrome in Severe COVID-19: Interleukin-6 Receptor Antagonist Tocilizumab May Be the Key to Reduce Mortality. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 105954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponti, G.; Maccaferri, M.; Ruini, C.; Tomasi, A.; Ozben, T. Biomarkers Associated with COVID-19 Disease Progression. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2020, 57, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Guo, H.; Zhou, P.; Shi, Z.L. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, F.; Di Spigna, G.; Vargas, M.; Iacovazzo, C.; Pinchera, B.; Spalletti Cernia, D.; Ricciardone, M.; Covelli, B.; Servillo, G.; Gentile, I.; et al. Soluble Urokinase Receptor as a Promising Marker for Early Prediction of Outcome in COVID-19 Hospitalized Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Valle, H.B.; Yaktine, A.L.; Taylor, C.L.; Ross, A.C. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D; Institute of Medicine: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Coates, P.M.; Betz, J.M.; Blackman, M.R.; Cragg, G.M.; Levine, M.; Moss, J.; White, J.D. (Eds.) Encyclopedia of Dietary Supplements; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, C.M.; Peacock, M. Calcium. Adv. Nutr. 2011, 2, 290–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawrzyniak, N.; Suliburska, J. Nutritional and health factors affecting the bioavailability of calcium: A narrative review. Nutr. Rev. 2021, 79, 1307–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairweather-Tait, S.J.; Teucher, B. Iron and calcium bioavailability of fortified foods and dietary supplements. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 60, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L. Calcium and bone metabolism indices. Adv. Clin. Chem. 2017, 82, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Endres, D.B. Mineral and bone metabolism. In Tietz Textbook of Clinical Chemistry and Molecular Diagnostics; Elsevier Health Sciences: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2006; pp. 1891–1924. [Google Scholar]

- Luciani, F.; Caroleo, M.C.; Cannataro, R.; Mirra, D.; D’Agostino, B.; Gallelli, L.; Cione, E. Immunological Response to SARS-CoV-2 Is Sustained by Vitamin D: A Case Presentation of One-Year Follow-Up. Reports 2021, 4, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F. High prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy and implications for health. Mayo Clin. Proc. Marzo 2006, 81, 353–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginde, A.A.; Mansbach, J.M.; Camargo, C.A. Association between serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D level and upper respiratory tract infection in the third national health and nutrition examination survey. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009, 169, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallelli, L.; Mannino, G.C.; Luciani, F.; de Sire, A.; Mancuso, E.; Gangemi, P.; Cosco, L.; Monea, G.; Averta, C.; Minchella, P.; et al. Vitamin D Serum Levels in Subjects Tested for SARS-CoV-2: What Are the Differences among Acute, Healed, and Negative COVID-19 Patients? A Multicenter Real-Practice Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Filippo, L.; Formenti, A.M.; Doga, M.; Frara, S.; Rovere-Querini, P.; Bosi, E.; Carlucci, M.; Giustina, A. Hypocalcemia Is a Distinctive Biochemical Feature of Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients. Endocrine 2021, 71, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martha, J.W.; Wibowo, A.; Pranata, R. Hypocalcemia is associated with severe COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2021, 15, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical Features of Patients Infected with 2019 Novel Coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi, B.; Alcock, J. Conflicts over calcium and the treatment of COVID-19. Evol. Med. Public Health 2021, 9, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Filippo, L.; Allora, A.; Locatelli, M.; Rovere Querini, P.; Frara, S.; Banfi, G.; Giustina, A. Hypocalcemia in COVID-19 is associated with low vitamin D levels and impaired compensatory PTH response. Endocrine 2021, 74, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, W.; Al Fahdi, F.; Al Salmi, I.; Al Khalili, H.; Gokhale, A.; Khamis, F. Serum Calcium and Vitamin D levels: Correlation with severity of COVID-19 in hospitalized patients in Royal Hospital, Oman. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 107, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nathan, L.; Lai, A.L.; Millet, J.K.; Straus, M.R.; Freed, J.H.; Whittaker, G.R.; Daniel, S. Calcium ions directly interact with the Ebola virus fusion peptide to promote structure–function changes that enhance infection. ACS Infect. Dis. 2019, 6, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellini, F.; Brivio, R.; Casati, M.; Cavallero, A.; Contro, E.; Brambilla, P. Low levels of total and ionized calcium in blood of COVID-19 patients. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2020, 58, e171–e173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, G.L. The role of calcium in inflammation-associated bone resorption. Biomolecules 2018, 8, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, P.; McAuley, D.F.; Brown, M.; Sanchez, E.; Tattersall, R.S.; Manson, J.J. COVID-19: Consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet 2020, 395, 1033–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldwell, F.T., Jr.; Graves, D.B.; Wallace, B.H. Pathogenesis of fever in a rat burn model: The role of cytokines and lipopolysaccharide. J. Burn Care Rehabil. 1997, 18, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

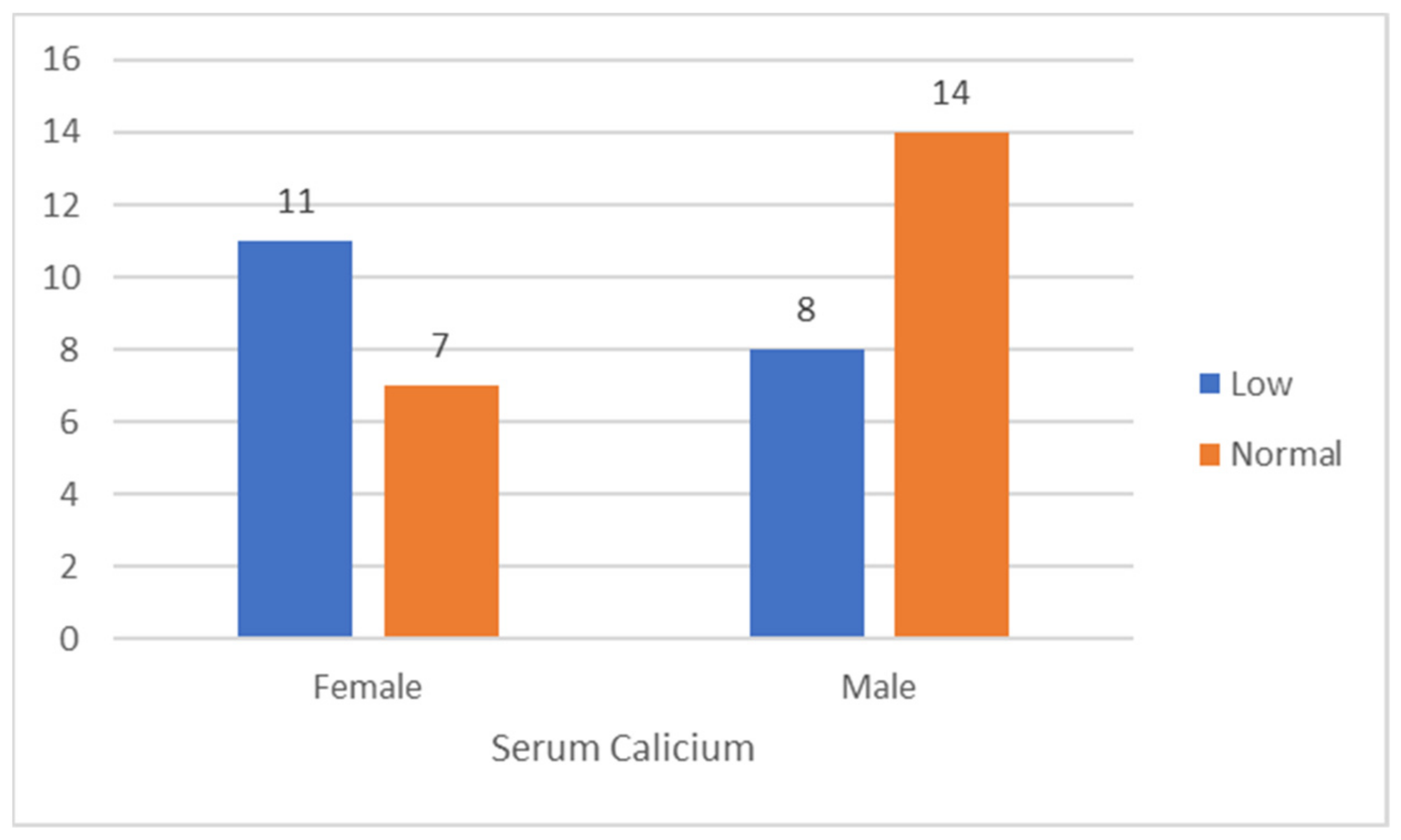

| Calcium | Low | Low in % | Normal | Normal in % | Total | Total in % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 11 | 61.1 | 7 | 38.9 | 18 | 45 |

| Male | 8 | 33.4 | 14 | 66.6 | 22 | 55 |

| Grand Total | 19 | 47.5 | 21 | 52.5 | 40 | 100 |

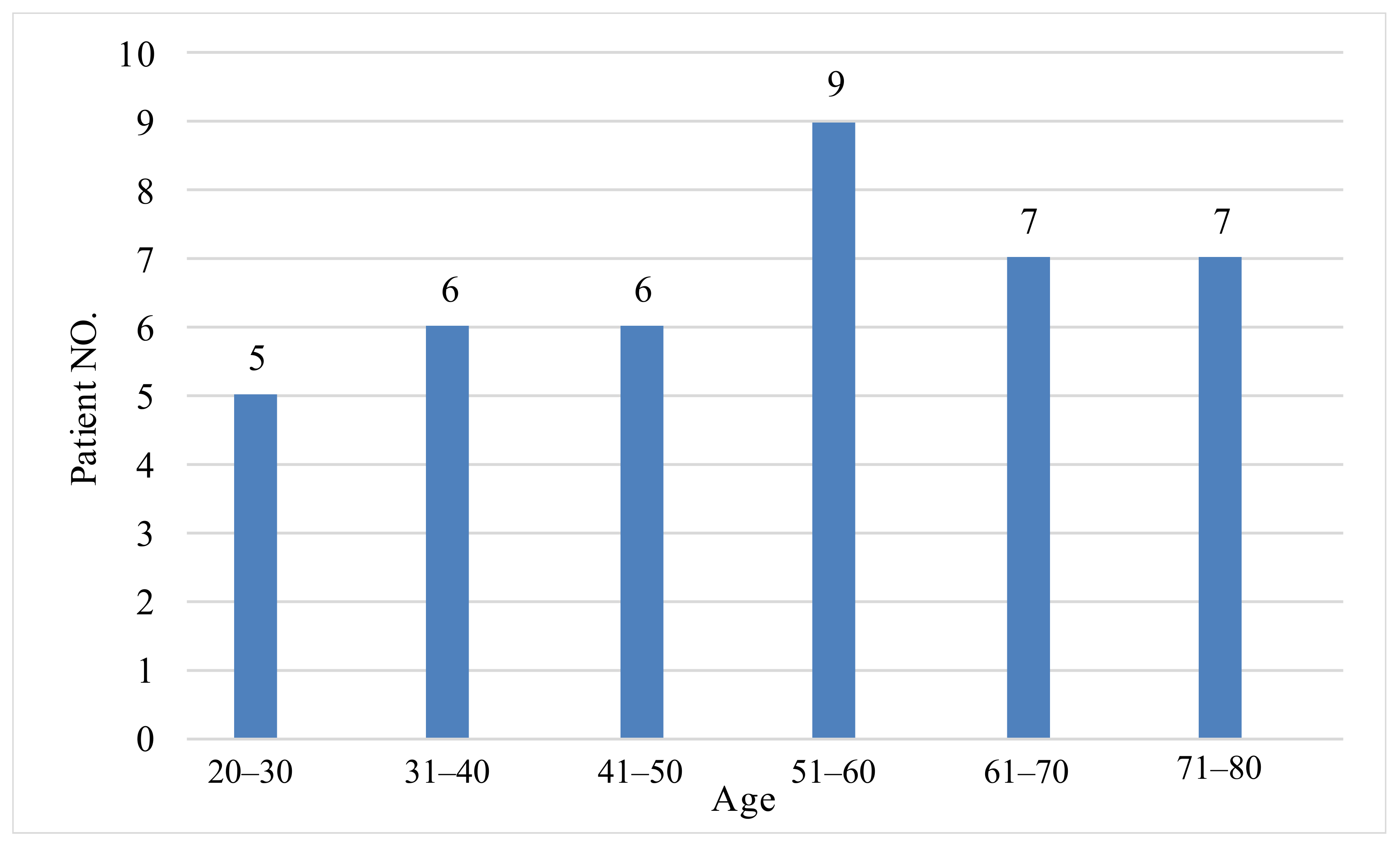

| N | Range | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | S.D. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 40 | 58.00 | 22.00 | 80.00 | 51.6500 | 16.13016 |

| Serum Calcium | 40 | 3.76 | 6.10 | 9.86 | 8.2400 | 1.09447 |

| Test Value = 8.5–10.5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t-Test | Degree of Freedom | Sig. (2-Tailed) | Mean Difference | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | ||

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Serum Calcium | −7.281 | 39 | 0.000 | −1.26000 | −1.5516 | −0.9684 |

| Levene’s Test for Equality of Variances | t-Test for Equality of Means | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t-Test | Degree of Freedom | Sig. (2-Tailed) | Mean Difference | ||||

| F-Test | Sig. | ||||||

| Serum Calcium | Equal variances assumed | 5.892 | 0.020 | 2.543 | 38 | 0.015 | 0.82828 |

| Equal variances not assumed | 2.465 | 30,499 | 0.020 | 0.82828 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hadi, J.M.; Hassan, S.M.J.; Saeed, M.M.M.; Hussein, B.K.; Ali, B.M.; Muhamad, L.E.; Abdullah, A.J.; Ali, N.N.; Rahman, H.A.; Sofihussein, H.Q.; et al. Estimation of Serum Calcium on the Severity and Mortality in COVID-19 Infections in Sulaymaniyah City, Kurdistan Region of Iraq: A Cross-Sectional Study. Clin. Pract. 2022, 12, 1001-1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract12060103

Hadi JM, Hassan SMJ, Saeed MMM, Hussein BK, Ali BM, Muhamad LE, Abdullah AJ, Ali NN, Rahman HA, Sofihussein HQ, et al. Estimation of Serum Calcium on the Severity and Mortality in COVID-19 Infections in Sulaymaniyah City, Kurdistan Region of Iraq: A Cross-Sectional Study. Clinics and Practice. 2022; 12(6):1001-1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract12060103

Chicago/Turabian StyleHadi, Jihad M., Shkar M. J. Hassan, Mudhafar M. M. Saeed, Bilal K. Hussein, Banwan M. Ali, Lava E. Muhamad, Ardalan J. Abdullah, Nzar N. Ali, Hawre A. Rahman, Hassan Q. Sofihussein, and et al. 2022. "Estimation of Serum Calcium on the Severity and Mortality in COVID-19 Infections in Sulaymaniyah City, Kurdistan Region of Iraq: A Cross-Sectional Study" Clinics and Practice 12, no. 6: 1001-1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract12060103

APA StyleHadi, J. M., Hassan, S. M. J., Saeed, M. M. M., Hussein, B. K., Ali, B. M., Muhamad, L. E., Abdullah, A. J., Ali, N. N., Rahman, H. A., Sofihussein, H. Q., & Abdul Aziz, J. M. (2022). Estimation of Serum Calcium on the Severity and Mortality in COVID-19 Infections in Sulaymaniyah City, Kurdistan Region of Iraq: A Cross-Sectional Study. Clinics and Practice, 12(6), 1001-1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract12060103