Abstract

Background: In an increasingly globalized context marked by growing professional mobility, establishing shared standards for assessing nursing competencies is essential. The licensure examination represents a critical gateway between academic preparation and professional practice. However, significant ambiguity remains regarding what competencies are assessed and how this assessment is conducted internationally. Objective: This scoping review aimed to map the international literature on nursing licensure examinations by comparing frameworks and domains, performance levels, and assessment tools to identify similarities and differences in the core competencies required for entry into practice. Methods: The review followed Arksey and O’Malley’s methodological framework. Comprehensive searches were conducted across PubMed, CINAHL, Scopus, ERIC, Cochrane Library, ProQuest, and OpenGrey databases. Studies addressing competency frameworks, performance levels, and assessment tools in undergraduate nursing licensure were included. Results: Twenty-three studies were analyzed. The most frequently cited framework was ‘Client Needs’. Competency domains commonly addressed patient needs, professional roles, and healthcare settings. The dominant performance level was cognitive, typically assessed through multiple-choice questions; practical skills were often evaluated via ‘bedside tests’. Despite variations in frameworks and domains, cognitive performance expectations and assessment tools showed some consistency. Conclusions: These findings underscore the need for a context-sensitive, internationally adaptable framework to promote fairness and support nurse mobility.

1. Introduction

In recent years, globalization has significantly increased the international mobility of workers and professionals. Among them, nurses are increasingly practicing in countries other than their own [1].

Furthermore, the increasing complexity of healthcare systems, multimorbidity, and the growing prevalence of chronic and acute conditions have further intensified the need to train highly competent nursing professionals capable of managing diverse and ever-changing clinical scenarios [2].

At the same time, global population aging has heightened the demand for qualified nurses, thereby incentivizing international mobility and underscoring the urgency of investing in nursing education [1]. The global shortage of nursing staff has long been recognized as a critical issue. Countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom have, for years, relied on recruiting qualified nurses from abroad to address domestic workforce gaps [3]. Although projections suggest that this shortage could decrease to 7.6 million by 2030 [4], it remains a persistent structural challenge that threatens the sustainability of healthcare systems.

In this increasingly interconnected healthcare landscape, establishing internationally shared competency standards is essential. Such standards enable nurses to operate effectively across different geographical settings, promoting health and protecting patients irrespective of national boundaries [1]. These standards typically define the minimum performance thresholds required for entry into clinical practice [1]. However, a barrier to harmonizing competency assessment lies in the lack of a universally accepted definition of competence. This challenge is compounded by the complexity of certification processes at the end of educational pathways [3].

The concept of competence has been a central topic in international discourse across various professions, including nursing, and has been interpreted differently depending on disciplinary and cultural contexts [5]. Garside and Nhemachena [6] describe it as an entity that is difficult to describe in concrete terms, while Cassidy [7] defines it as a combination of knowledge, skills, and attitudes. A more comprehensive perspective is proposed by Meretoja et al. [8], who define competence as the functional capacity to integrate knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values in specific care settings.

In most contexts, competency certification is formalized through a final licensure examination, which serves as the official mechanism for assessing the readiness of nursing graduates and authorizing their entry into the profession [9]. However, international regulatory frameworks differ widely in how licensure examinations are implemented. Some countries have long-established systems, while in others, regulatory processes are still evolving [10]. For example, the United States, China, Japan, and Thailand require a national licensure examination [11]. In contrast, in Spain, completion of a university degree allows direct registration with the professional board, without further testing [10]. A similar model applies in England, where academic qualifications permit registration with the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) without a final examination [10]. In Italy, however, a licensure examination is mandatory to formally certify both theoretical and practical competencies [10,11].

In this review, the term “nursing licensure examination” refers to an examination administered by governmental or professional regulatory bodies, typically at the national or state level, which authorizes graduates of accredited nursing programs to enter professional practice. These examinations are distinct from academic or university-level assessments and are usually required regardless of the institution where the nursing degree was obtained. The structure, content, and regulatory framework of licensure examinations vary internationally, reflecting differences in educational systems and professional standards [10].

Regardless of the specific methods used, all systems share the expectation that, upon completing their education, nursing students must demonstrate the competencies necessary to address priority health problems and deliver safe, effective care [1,2]. Several studies have highlighted significant variation not only between countries, but also within individual national contexts regarding the competencies considered ‘core’ for new graduates [11,12,13]. To address these discrepancies, academic and professional community have worked to develop competency frameworks, domains, and performance levels conceptualized as expected learning outcomes [14].

In the United States, for example, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) published The Essentials: Core Competencies for Professional Nursing Education (2021), which outlines a comprehensive framework for competency-based nursing curricula and serves as a national standard for CCNE-accredited institutions and reflects a growing emphasis on harmonizing education with professional expectations and licensure requirements [15].

In the European context, these levels generally refer to the Dublin Descriptors [16], which include knowledge and understanding, applying knowledge and understanding, making judgements, communication skills, and learning skills.

In the European context, the Bologna Process represented a significant effort to harmonize education systems across countries; the process was operationalized through the Tuning Educational Structures in Europe project [17]. Within the field of nursing, this initiative led to the development of two key competency frameworks: the Tuning Nursing Specific Competences [18], which outlines 47 competencies grouped into six domains, and the EFN Competency Framework [19], which is also organized into six domains. In parallel, several studies have described the tools used for the evaluation of competencies during the licensure examination. These tools include open- or closed-ended response tests, clinical cases discussions, bedside practical assessments, procedural protocols, and structured evaluations such as the objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) [10,11,12,13]. However, preliminary bibliographic searches conducted in major databases including PubMed, Cochrane, JBI, and PROSPERO revealed a limited number of studies that examine in detail what is assessed and how the assessment is conducted during the nursing licensure examination [13,20,21].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Objective

The objectives of this study were as follows:

- To map the international literature on the nursing licensure examination;

- To compare the frameworks and related domains of the competencies assessed the performance levels, and the tools used for their assessment, to highlight convergences and divergences in the core competencies assessed in the licensure examination.

2.2. Study Design

The scoping review represents a methodological approach useful for mapping and integrating the available evidence on a given phenomenon.

This study adopted scoping review design, which is particularly appropriate for topics that are complex or heterogeneous and have not been extensively reviewed. The scoping review approach was deemed suitable to map the breadth and depth of the existing international literature on nursing licensure examinations, which vary in purpose, structure, and implementation across countries. Unlike systematic reviews, scoping reviews do not aim to critically appraise individual studies but rather to identify and categorize existing evidence, highlight knowledge gaps, and provide an overview of key concepts and approaches.

This study was conducted in accordance with the methodological framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley [22], which is divided into five stages: (1) the definition of the research question; (2) the identification of relevant studies; (3) the selection of studies; (4) data collection and organization; and (5) the synthesis and presentation of results.

While Arksey and O’Malley’s scoping review framework provides a robust methodological foundation for mapping existing literature, it does not inherently include a theoretical lens for interpreting the phenomena under study.

To enhance the conceptual understanding of nursing licensure examinations, this review acknowledges the potential relevance of established theoretical models such as the job demand–resources (JD-R) model [23], which explores how job demands and available resources impact individual well-being and performance. Additionally, the conservation of resources (COR) theory [24] offers insight into how new nursing graduates manage personal and professional resources during stressful transitions, such as licensure exams. Trauma Theory [25] may also provide a valuable framework for understanding the emotional challenges faced by internationally mobile nurses navigating unfamiliar certification processes.

No protocol has been registered with the Open Science Framework.

2.3. Stage 1, Identifying the Research Question

To answer the objective of the review, the following research questions were formulated: What competency framework is used for assessment during the nursing licensure examination? What are the expected performance levels for passing the licensure examination? Which tools are used for the evaluation of competencies?

In this review, ‘nursing licensure examination’ refers to the final examination at the bachelor’s degree level, which clarifies the transition from student status to that of a licensed professional.

2.4. Stage 2, Identifying Relevant Studies

In December 2022, preliminary searches were conducted in PubMed, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, JBI’s Evidence-based Practice Database (Ovid) and PROSPERO that confirmed the absence of other protocols or of scoping reviews already published on the topic.

The databases consulted for this review were: PubMed, CINAHL (EBSCO), Scopus (Elsevier), ERIC, and Cochrane Library. The gray literature search included ProQuest Dissertations and Theses and the OpenGrey portal (www.opengrey.eu/). Studies published between 1 January 2000, and 1 December 2024, in English and with an abstract, were included. The selected time interval is justified by the launch, in 1999, of the Bologna Process, a European intergovernmental agreement aimed at reforming higher education through the introduction of a system based on three comparable educational cycles [16].

The Bologna Process also represented an important impetus to the harmonization of educational standards at the international level, potentially influencing the emergence of new models of licensure examination.

The keywords (thesaurus terms and text words) appropriate for the research questions, were combined using the Boolean operators AND, OR, or NOT and adapted to each database. The full texts of the selected articles were searched manually to identify further relevant sources (Appendix A.1).

International peer-reviewed studies with results pertaining to frameworks and domains of competence, performance levels, and competency assessment tools used during the licensure examination were included. The review included: quantitative studies (experimental, quasi-experimental, analytical, and descriptive observational), systematic or scoping reviews, qualitative studies, expert opinions, discussion articles and the gray literature (e.g., technical reports, summaries). Studies referring to licensure examinations of health professions other than nursing; articles published before 2000 or not in English; reports, conference proceedings, research protocols, and posters were excluded.

2.5. Stage 3, Study Selection

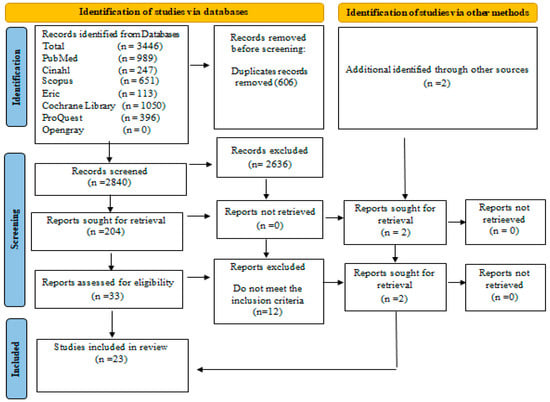

The search yielded 3446 records, which were subsequently imported into EndNote Clarivate Analytics v.14.0. Following the removal of duplicates (n= 606), two reviewers (F.P. and A.S.) screened the titles and abstracts. After a pilot test conducted on 23 studies, the reviewers proceeded with independent screening. Full texts of articles deemed potentially relevant were retrieved for further evaluation. In instances of uncertainty or disagreement, a third reviewer (A.M.) was consulted to reach consensus. The selection process followed the scoping review checklist [26].

The PRISMA-ScR is a 27-item checklist designed to improve the clarity, completeness, and transparency of scoping reviews, particularly those addressing complex or diverse research areas [27].

In the planning and reporting phases of this review, the checklist was used to ensure that key components, including the review rationale, detailed eligibility criteria, comprehensive search strategy, selection process, data representation methods, and summary of findings, were explicitly described. Use of the PRISMA-ScR also supported a structured presentation of findings and enabled better alignment with the methodological standards recommended by the Joanna Briggs Institute.

A complete PRISMA-ScR checklist is included in the Supplementary Materials to ensure transparency and reproducibility (see Supplementary Table S1) and the results were reported in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR flow diagram [26].

2.6. Stage 4, Data Charting

Data extraction was conducted using a systematic approach [22]. Two independent reviewers (F.P. and A.S.) employed a purpose-built extraction tool (Appendix A.2), which included the following elements: study characteristics, competency frameworks and domains, performance levels, and assessment tools. The tool was refined throughout the extraction process, with all modifications shared among the research team. When critical information was missing, the authors of the included studies were contacted to request its provision.

2.7. Stage 5, Collating and Summarizing

All authors agreed on the method of presenting the review data following a thorough, collaborative analysis of the results. The methodological quality of the studies included was initially assessed independently by two reviewers (F.P. and A.S.), using the tools developed by the Joanna Briggs Institute [28]. (J). Agreement was achieved through direct comparison and the use of an evaluation grid comprising four response options: “yes,” “no,” “unclear,” and “not applicable.”

For each of the three research questions addressed in the scoping review, the extracted data—pertaining to the type and purpose of the studies, as well as key findings—were organized and summarized in tabular form. This included information on the competency frameworks and domains assessed during the licensure examination, the expected performance levels, and the assessment tools employed.

Narrative synthesis accompanied the tabular data, highlighting similarities and differences among the studies for each variable considered. This approach aimed at providing a comprehensive and comparative overview of the practices adopted across various international contexts.

3. Results

3.1. General Description of the Studies

Twenty-three records were included in this review (Figure 1), comprising twenty original research articles, two doctoral dissertations, and one expert opinion, all published between 1 January 2000, and 1 December 2024.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram of literature search [26].

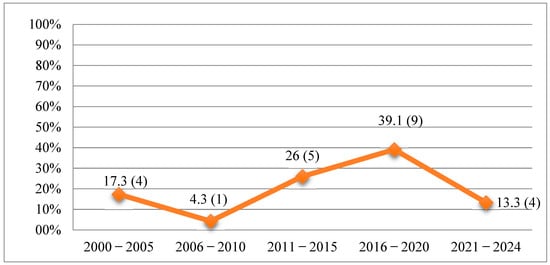

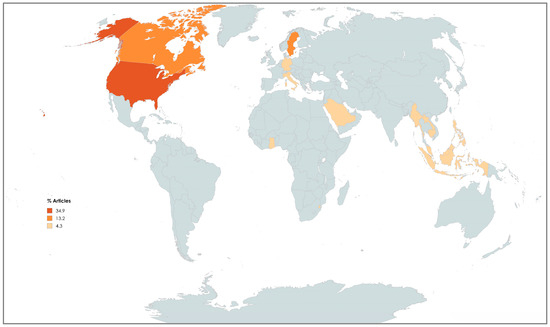

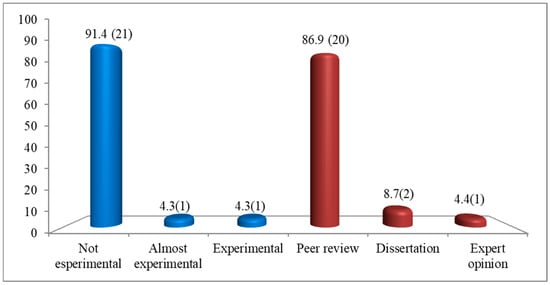

Most selected records were published during the five-year period from 2016 to 2020 (n = 9, 39.1%) as shown in Figure 2. Most studies were conducted in America (n = 12), followed by Europe (n = 5), Asia (n = 4), and Africa (n = 2) (Figure 3). Further details regarding the characteristics of the included studies are presented in Figure 4 and Table 1.

Figure 2.

Percentage and number of articles published by year/class (N = 23).

Figure 3.

Choropleth of document distribution by geographic region of studies that have been conducted in following countries: Canada 13.2; United States of America 34.9; Commonwealth Caribbean 4.3; Ghana 4.3; Eswatini 4.3; ASEAN 4.3; Korea 4.3; Indonesia 4.3; Saudi Arabia 4.3; Germany 4.3, Italy 4.3; Sweden 13.2.

Figure 4.

The number and percentage of studies categorized by type in the scoping review (N = 23). Legend: blue color columns = study design; red color columns = type of study.

Table 1.

Included studies (ordered alphabetically by author name).

3.2. Framework Competencies Assessed in the Nursing Licensure

The objective of this review was to map the international literature on nursing licensure examinations, with a focus on competency frameworks and domains, expected performance levels, and assessment tools. Data analysis identified 13 competency frameworks described in 21 of the 23 included articles (Table 2).

Table 2.

Framework and domains of competencies.

In one of these studies, the framework was presented without specifying its competency domains [45] while another study reported only the domains [44], and one study did not include either a framework or domains [36] (Table 2).

Regarding performance levels, five theoretical reference models were identified. Eleven studies explicitly referenced these frameworks, while eight studies reported performance levels without indicating a theoretical basis [29,34,36,40,41,43,44,45] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Expected performance levels.

All 23 studies included in the review reported on the assessment tools used in nursing licensure examinations. These tools can be categorized into six types for cognitive testing and three for practical evaluation (Table 4).

Table 4.

Types of tools used for competencies assessment.

In response to the first review question—"What competency framework is used for assessment during the nursing licensure examination?”—a total of 13 distinct competency frameworks were identified and are detailed in Table 2. These frameworks were described in 21 out of the 23 included studies. The most frequently cited was the Client Needs framework, which appeared in nine studies—eight conducted in the United States [33,35,41,43,46,47,48,49] and one in Canada [40]. This framework is structured into four domains—safe care environment, health promotion, disease prevention, and health promotion—and emphasizes the identification and fulfillment of patient needs across various care settings.

Other competency frameworks emerged across the included studies, each reflecting the specific context of the country or region in which it is applied. For example, the SNLE Guideline [29], adopted in Saudi Arabia, includes four domains; the NMC Standards [30], used in Ghana, consist of six domains; and the SoS Swedish Declaration [31], implemented in Sweden, is composed of four domains. In Canada, the CASN framework [32,51], identifies six domains, while in the ASEAN region, the AJCCN framework encompasses five domains shared among ten member states.

In addition, the QSEN framework [21], also adopted in Sweden, is structured into six domains; the Tuning Nursing Specific Competences [38], used in Italy, includes five domains; and the ENC Framework [37], applied in Eswatini, is composed of seven domains with a focus on person-centered care. The ETPC [39], used in Canada, the competencies grouped into six domains, while the CARICOM Blueprint [42], is derived from the curricula of 13 nursing schools across the Caribbean. The AINEC minimum standards [45], implemented in Indonesia, does not define specific domains. Finally, the Angoff method [50], used in South Korea, establishes minimum competency thresholds through eight domains as part of the performance level description (PLD).

The predominance of the Client Needs framework in the included studies can be attributed to the high number of U.S.-based publications, many of which are focused on predicting students’ academic and professional success through outcome measures such as exit exams, GPA, and NCLEX-RN scores [33,35,40,41,43,46,49].

Regarding the second research question—"What are the expected performance levels for passing the licensure examination?”—five theoretical frameworks used to define performance expectations in nursing licensure examinations were identified, as detailed in Table 3. In the table, studies were classified as “not specified” when there was no explicit reference to any performance level framework, such as Bloom’s taxonomy [52], Miller’s pyramid [53], or similar hierarchical models. In these cases, it was not possible to infer a performance level due to the absence of detailed descriptors or structured classification criteria provided by the authors.

Among the frameworks identified, Bloom’s taxonomy was the most frequently cited, being adopted in five studies [33,46,47,48,49]. The revised version of Bloom’s taxonomy by Anderson and Krathwohl [54] organizes cognitive skills into six hierarchical levels: Remember, Understand, Apply, Analyze, Evaluate, and Create.

Miller’s pyramid was employed in three studies [21,31,32], providing a model of clinical competence that progresses through four stages: Knows, Knows How, Shows How, and Does [53].

The national clinical judgment measurement model (NCJMM) appeared in one study [35]. This model, which is grounded in Tanner’s Clinical Judgment Model [55]. outlines four levels of clinical reasoning.

The Dublin descriptors, used in one Italian study [38], define five levels of expected learning outcomes at the conclusion of a degree program, as established by the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research [56].

Lastly, the Standard Clinical Competencies Record Book (SCCRB) serves as the official framework for performance assessment in Eswatini [37].

The analysis highlights the predominance of Bloom’s taxonomy, particularly in U.S.-based studies, where the emphasis on cognitive development—especially within the domains of knowledge and clinical judgment—is viewed as a critical foundation for professional readiness [33,35,41,43,46,49].

Regarding the third research question—“Which tools are used for the assessment of competencies?”—two main categories of assessment emerged—cognitive and practical—as detailed in Table 4.

Cognitive assessment was reported in all 23 included studies and was most frequently conducted through written examinations (Table 4).

Additionally, some studies reported the use of oral examinations as part of the cognitive assessment [38,44].

Six distinct types of cognitive assessment tools were identified across the studies. Multiple-choice questions (MCQs) were the most commonly employed, appearing in 17 studies either in paper-based or computerized formats. Modified essay questions (MEQs), which involve clinical scenarios with open-ended questions, were reported in two studies. A hybrid format combining MCQs and MEQs was found in three studies. Open-ended response tests, focused on recall and argumentation, were reported in two studies. Clinical case resolution, either real or simulated and presented in written or oral formats with an emphasis on problem-solving, was described in five studies. Finally, discussion of protocols and procedures was used in two studies as part of competency evaluation (Table 4).

Overall, MCQs represented the most frequently used cognitive assessment tool, followed by clinical case resolution. Notably, only one study did not specify the type of written examination employed [44].

Practical assessments were classified into three main modalities. Simulated clinical cases (OSCEs) were described in two studies, where standardized stations were used to evaluate clinical performance [30,38]. Bedside tests, applied in five studies, evaluated student performance directly in clinical settings either individually or in teams [21,31,36,38,44]. Lastly, decontextualized practical tests, focused on isolated technical skills, were reported in one study [38].

Among the studies that included practical testing, bedside tests were the most commonly used, followed by OSCEs. However, 17 studies did not report any form of practical assessment. Notably, only one study [44] incorporated all three types of assessments: written, oral, and practical.

4. Discussion

The objective of this scoping review was to map the international literature on nursing licensure examinations, comparing the frameworks and domains of assessed competencies, the expected performance levels, and the tools used in assessment.

The analysis revealed considerable heterogeneity in the reference frameworks used across studies. Competency domains are structured according to different and often non-overlapping categorical systems, which complicate the establishment of standardized international benchmarks. In general, the frameworks reference three primary areas: patient needs, nursing roles/functions, and areas of care [32,33,34,35,37]. As noted by Oermann et al. [57], these categories are often interconnected, reflecting the holistic nature of nursing practice, where the assessment of competencies must be contextualized within clinical, relational, and organizational dimensions.

This variability reflects the influence of differing educational models and healthcare systems across countries. For instance, in Anglo-Saxon contexts, the emphasis tends to be on patient-centered approaches and clinical skills, whereas other regions may prioritize managerial or ethical–deontological competencies [58,59]. This differentiation aligns with the AACN position, which advocates for the definition of competencies that respond to local health needs while adhering to minimum global standards [15].

Despite these differences, a common thread among the frameworks is the attention to the multidimensional needs of individuals physical, psychological, social, and spiritual underscoring the centrality of person-centered care in nursing [21,32].

Notably, domains such as “safety” and “health promotion” are recurrent across frameworks, echoing the literature that identifies patient safety as one of the core competencies in healthcare [60].

To better highlight the commonalities and distinctions among the most frequently assessed areas, a brief synthesis was carried out regarding the predominance of domains and competencies. Across the analyzed frameworks, a consistent presence was noted for domains such as clinical reasoning, safety, communication, health promotion, and care coordination. These areas represent foundational expectations in nursing education worldwide and confirm a convergence toward shared professional priorities. While other competencies—such as leadership, digital literacy, and ethical decision-making—were present in some contexts, their distribution appeared more variable and context-dependent. This reflection, albeit qualitative, aligns with one of the core aims of this review: to identify prevailing trends and support a more coherent definition of common standards.

With respect to performance levels, although several theoretical models are identified including Bloom’s taxonomy, Miller’s pyramid, the national clinical judgment measurement model (NCJMM), and the Dublin descriptors there is substantial convergence in the expectations. All frameworks describe a developmental trajectory of competencies, from foundational knowledge to higher-order skills such as critical thinking and evaluation [54,55]. This progression reflects the recommendations of international nursing education guidelines, which emphasize the need to train nurses capable of exercising sound clinical judgment, particularly in complex and dynamic environments [4].

One of the most critical issues emerging from this review is the translation of these performance levels into actual assessment tools. Although theoretical frameworks are often well-structured, the assessment of competencies remains heavily weighted toward the cognitive domain. This finding, consistently reported across all included studies, is also corroborated by recent systematic reviews [61], which highlight ongoing challenges in evaluating psychomotor and relational skills.

The theoretical models referenced in the Methods section—namely the Job Demand–Resources Model, the Conservation of Resources Theory, and Trauma Theory—may also serve as useful interpretive tools to contextualize the institutional and emotional demands associated with licensure examinations. While not fully applied in this review, these models offer promising avenues to deepen the conceptual analysis of how candidates experience and respond to the pressures of certification systems across different settings. To enrich the interpretation of findings, future iterations of this review could benefit from anchoring the synthesis within a theoretical framework such as the Job Demand–Resources Model or the Conservation of Resources Theory. These models may offer additional explanatory value when examining how different licensure systems place varying cognitive, emotional, and institutional demands on new nursing graduates [23,24,25].

In order to analyze how different licensure systems influence the experience of newly graduated nurses, it is essential to consider not only the theoretical framework of the demands placed on them, but also the concrete tools through which these competencies are actually assessed. The multiple-choice question (MCQ) format is by far the most frequently used tool. While MCQs offer advantages in terms of standardization, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness [62], they are limited in their ability to assess complex reasoning and clinical judgment [63]. To address this gap, the Next-Generation NCLEX (NGN) has recently been introduced in the United States. Based on the NCJMM, the NGN incorporates complex item formats built around simulated clinical scenarios, aiming to capture both theoretical knowledge and decision-making processes [35,64]. This model represents a promising direction for other countries seeking to enhance the validity and reliability of licensure assessments.

In contrast, practical assessments such as bedside examinations, objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs), or isolated skills tests remain underrepresented. This trend is consistent with the existing literature that identifies practical skill assessment as a resource-intensive process, requiring significant human, logistical, and ethical investment [65]. Nonetheless, several authors argue that practical skills assessment, particularly through simulation, is essential to prepare nurses for real-world clinical demands [66].

Interestingly, while the frameworks and competency domains exhibit high variability, the tools used for cognitive assessment show a greater degree of consistency. In centralized systems, such as that of United States, the use of standardized national exams contributes to this uniformity. In more decentralized contexts such as Europe, Africa and the Southeast Asian, where competencies are defined at the national or regional level, greater variability is observed [34,44,50].

To address this fragmentation, Europe has promoted initiatives aimed at harmonizing nursing education and assessment, such as the Tuning Project [17], and the EFN Competency Framework [19]. These initiatives offer a shared language for defining nursing competencies and may serve as a foundation for developing common evaluation criteria. Such standardization efforts are essential for fostering equity, transparency, and professional mobility within and across healthcare systems [18,38].

5. Strengths and Limitations

A key strength of this review lies in its systematic and comparative mapping of the international literature concerning nursing licensure examinations. By analyzing three fundamental dimensions competency frameworks and domains, expected performance levels, and assessment tools—the review offers a comprehensive and up-to-date perspective on the evaluation practices adopted in diverse geographical and cultural contexts. It also identified both convergences and divergences in assessment approaches, shedding light on the influence of regulatory, educational, and cultural factors in shaping national certification systems. These findings generate important insights for policy-makers, educators, and professional bodies, advocating for the design of shared, adaptable models to guide future licensure examinations.

Another notable strength is the applicative relevance of the results. The review supports the development of minimum common standards that could enhance the quality and equity of transitional pathways from education to professional practice. Furthermore, the inclusion of the literature from a range of international contexts contributes to the external validity of the findings.

However, this review also presents some limitations. First, the analysis was restricted to bachelor’s-level licensure examinations, excluding master’s level certifications and broader processes of competency assessment across the educational continuum. As such, the results apply only to first-level final examinations, omitting important evaluative dynamics present in advanced educational stages.

A further limitation to consider is the focus on the Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) licensure examinations, which excludes other educational pathways such as the Associate Degree in Nursing (ADN) commonly found in the United States. Although this distinction was noted in the Limitations section regarding the exclusion of master’s level certifications, it is important to explicitly acknowledge that various educational levels may share the same licensure examination, potentially influencing the generalizability of the findings. Future research could expand the scope to include these diverse educational pathways and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the licensure process across all nursing qualification levels.

Second, the perspectives of students and evaluators were not included, nor were qualitative studies that could have enriched the findings with insights into subjective experiences, critical issues, and contextual nuances related to certification processes. This represents an important avenue for future research.

Lastly, despite a rigorous selection strategy, the available literature was heterogeneous in terms of terminology, framework structure, and completeness of reporting. Finally, despite a rigorous selection strategy, the available literature was heterogeneous in terms of terminology, framework structure, and documentation completeness. Furthermore, there was a notable predominance of studies from Anglo-Saxon countries, which may have influenced interpretation and limited the representation of other cultural and regional perspectives. Therefore, a potential limitation of this scoping review is the risk of publication bias, particularly due to the predominance of studies from the United States and the inclusion of literature primarily in English. This may have influenced the synthesis of findings and limited their generalizability to other regions and linguistic contexts.

6. Conclusions

This scoping review highlighted significant heterogeneity in the competency frameworks used internationally for nursing licensure examinations, both in terms of structural organization and the domains considered. Such variability reflects the diversity of healthcare systems, educational models, and socio-health priorities across countries.

Importantly, cultural and religious factors also play crucial roles in shaping nursing competencies and the content and delivery of licensure examinations. In some countries, cultural norms and religious laws influence healthcare practices, which consequently impact the definition of core competencies and assessment approaches. Recognizing these influences is essential to understanding international differences and fostering culturally sensitive competency frameworks.

Notwithstanding these differences, the review also identified key areas of convergence across the competency frameworks. Most models emphasize patient-centered care, clinical judgment, safety, and health promotion as essential domains for entry-level nursing practice. This suggests the existence of a shared set of core competencies that transcends national boundaries and may serve as a foundation for global standards. At the same time, differences in emphasis—such as the role of technology, communication, or ethical–legal aspects—reflect local priorities and contexts, highlighting the importance of maintaining both global alignment and local adaptability.

Nevertheless, a shared core emerges across frameworks, centered on the multidimensional needs of individuals and the promotion of health confirming the centrality of these concepts in defining global nursing competencies.

Despite differences in reference models for performance levels, most studies converge on a similar trajectory: beginning with foundational knowledge and advancing toward clinical judgment. This alignment underscores the growing emphasis on critical thinking and clinical reasoning as essential components of professional nursing practice.

From a methodological perspective, the most employed assessment tools are cognitive in nature, particularly multiple-choice questions (MCQs). In contrast, practical assessments remain underutilized, despite increasing evidence of their value for both educational and evaluative purposes. This imbalance underscores the urgent need to revise current evaluation models to better reflect the full spectrum of nursing competencies including relational, psychomotor, and ethical–deontological dimensions.

In light of these findings, there is a clear need to promote the harmonization of competency frameworks at the international level. Such efforts should aim to establish shared yet flexible standards that are responsive to local contexts while fostering comparability, equity, and professional mobility. In this regard, European initiatives such as the Tuning Nursing Project and the EFN Competency Framework represent promising models for advancing the quality and transparency of nursing education and certification processes.

Ultimately, ensuring equity and rigor in the evaluation of nursing competencies is a critical challenge for the future of the profession. Only through an integrated approach linking education, clinical practice, and professional regulation can we develop licensure systems that are relevant, robust, and aligned with the overarching goal of improving healthcare quality.

Future studies should aim to expand the scope of analysis by incorporating qualitative research, exploring advanced educational pathways, and evaluating alternative models of competency certification. Particular attention should be given to the development and implementation of integrated assessment systems that span the full trajectory of nursing education from academic training to professional practice.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nursrep15080299/s1: Table S1: PRISMA_2020_checklis [27].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.P., A.M. and M.G.D.M.; methodology, F.P., A.S. and C.M.; software, F.P.; formal analysis, F.P., A.M., C.M., G.P. and N.M.; resources, F.P., A.M. and N.M.; data curation, F.P., A.M. and G.P., writing—original draft preparation, F.P., A.M. and M.G.D.M.; writing—review and editing, F.P. and A.M.; visualization, M.P. and M.G.D.M.; supervision, C.M., M.P. and M.G.D.M.; project administration, A.M. and M.G.D.M.; funding acquisition, A.S. and N.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research was funded by Centre of Excellence for Nursing Scholarship—OPI Rome—Italy, grant number “1.22.1” and “The APC was funded by Centre of Excellence for Nursing Scholarship—OPI Rome—Italy”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or Supplementary Materials.

Public Involvement Statement

No public involvement in any aspect of this research.

Guidelines and Standards Statement

This manuscript was drafted against The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews (See Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials).

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Artificial intelligence tools (ChatGPT Plus, OpenAI) were used exclusively for language editing and grammar correction of the manuscript. No AI tools were used for data analysis, interpretation of results, or drawing scientific conclusions. The graphical abstract was created manually by the authors using a predefined template available in the free version online of application Canva, without the use of AI-based features.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Centre of Excellence for the OPI Nursing Scholarship in Rome for supporting the research. While preparing this manuscript, ChatGPT Plus (OpenAI) was used exclusively for language editing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication. All individuals included in this section have consented to the acknowledgment.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AACN | American Association of Colleges of Nursing |

| ADN | Associate Degree in Nursing |

| AIDS | Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome |

| AINEC | Association of Indonesian Nurse Education Centre |

| AJCCN | ASEAN Joint Coordinating Committee on Nursing |

| ASEAN | Association of Southeast Asian Nations |

| ATI | Assessment Technologies Institute |

| BSN | Bachelor of Science in Nursing |

| CASN | Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing |

| CAT | Computerized Adaptive Testing |

| CEBN/ECBSI | Canadian Examination for Baccalaureate Nurses/l’Examen Canadien du Baccalaureate en Sciences Infirmières |

| CRNE | Canadian Registered Nursing Exam |

| CGPA | Cumulative Grade Point Average |

| COR | Conservation of Resources |

| EFN | European Federation of Nurses Associations |

| ENC | Eswatini Nursing Council |

| ETP | Entry to Practice Competencies |

| ETPC | Entry to Practice Competencies Client-Centered |

| GSE | General Self-Efficacy |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| INCE | Indonesian Nursing Competency Examination |

| JD-R | Job Demand–Resources |

| KNLE | Korean Nursing Licensing Examination |

| MCQs | Multiple-choice question |

| MEQ | Modified Essay Questions |

| NCFE | Swedish National Clinical Final Examination |

| NCLEX | National Council Licensure Examination |

| NCLEX-RN | National Council Licensure Examination for Registered Nurses |

| NCSBN | National Council of State Boards of Nursing |

| NCJMM | National Clinical Judgment Measurement Model |

| NGN | Next-Generation NCLEX |

| NL | Newfoundland and Labrador |

| NLE | Nursing Licensing Exam |

| NMC | Nursing and Midwifery Council |

| NMC-LE | Nursing and Midwifery Council- Licensure Examination |

| OSCEs | Objective Structured Clinical Examination |

| PLD | Performance Level Description |

| QSEN | Quality and Safety Education for Nurses |

| RN | Registered Nurse |

| SCCRB | Standard Clinical Competencies Record Book |

| SNLE | Saudi Nursing Licensure Examination |

| TB | Tuberculosis |

| TEAS | Test of Essential Academic Skills |

| USA | United States of America |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Search Strategy (PubMed)

| Search | Query | Results |

| #9 | Search: (((((nursing student*[Title/Abstract]) AND (undergraduate or bachelor or university)) OR (“Students, Nursing”[Mesh])) AND (“final exam*”[Title/Abstract] OR “licensure exam*”[Title/Abstract] OR licensure*[Title/Abstract])) OR (“Licensure, Nursing”[Mesh])) NOT (pre-licensure[Title/Abstract]) Filters: Abstract, English, from 2000/1/1–2024/12/1 | 989 |

| #8 | Search: #6 + #7 (((((nursing student*[Title/Abstract]) AND (undergraduate or bachelor or university)) OR (“Students, Nursing”[Mesh])) AND (“final exam*”[Title/Abstract] OR “licensure exam*”[Title/Abstract] OR licensure*[Title/Abstract])) OR (“Licensure, Nursing”[Mesh])) NOT (pre-licensure[Title/Abstract]) | 4809 |

| #7 | Search: pre-licensure [Title/Abstract] | 455 |

| #6 | Search: #3 + #2 + #1 + #5 + #4 ((((nursing student*[Title/Abstract]) AND (undergraduate or bachelor or university)) OR (“Students, Nursing”[Mesh])) AND (“final exam*”[Title/Abstract] OR “licensure exam*”[Title/Abstract] OR licensure*[Title/Abstract])) OR (“Licensure, Nursing”[Mesh]) | 4991 |

| #5 | Search: “final exam*”[Title/Abstract] OR “licensure exam*”[Title/Abstract] OR licensure*[Title/Abstract] | 9223 |

| #4 | Search: “Licensure, Nursing”[Mesh] | 4670 |

| #3 | Search: nursing student*[Title/Abstract] | 20,684 |

| #2 | Search: undergraduate OR bachelor OR university | 16,184,164 |

| #1 | Search: “Students, Nursing”[Mesh] | 30,382 |

Appendix A.2. Data Extraction Instrument

| Author (s) | |

| Year of publication | |

| Country | |

| Study design | |

| Population | |

| Aim | |

| KEY FINDINGS | |

| Which competency framework is assessed during the nursing licensure? | |

| What are the expected performance levels? | |

| What types of tools are used for competencies assessment? | |

References

- Drennan, V.M.; Ross, F. Global nurse shortages—The facts, the impact and action for change. Br. Med. Bull. 2019, 130, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.H.; Sloane, D.; Griffiths, P.; Rafferty, A.M.; Bruyneel, L.; McHugh, M.; Maier, C.B.; Moreno-Casbas, T.; E Ball, J.; Ausserhofer, D.; et al. Nursing skill mix in European hospitals: Cross-sectional study of the association with mortality, patient ratings, and quality of care. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2017, 26, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Aungsuroch, Y. Current Literature Review of Registered Nurses’ Competency in the Global Community. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2018, 50, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030. 2016. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/250368/9789241511131-eng.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Charette, M.; McKenna, L.G.; Deschênes, M.F.; Ha, L.; Merisier, S.; Lavoie, P. New graduate nurses’ clinical competence: A mixed methods systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 2810–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garside, J.R.; Nhemachena, J.Z. A concept analysis of competence and its transition in nursing. Nurse Educ. Today 2013, 33, 541–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, S. Interpretation of competence in student assessment. Nurs. Stand. 2009, 23, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meretoja, R.; Isoaho, H.; Leino-Kilpi, H. Nurse competence scale: Development and psychometric testing. J. Adv. Nurs. 2004, 47, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benton, D.C.; Catizone, C.A.; Chaudhry, H.J.; DeMers, S.T.; Grace, P.; Hatherill, W.A.; Monahan, M.J. Bibliometrics: A means of visualizing occupational licensure scholarship. J. Nurs. Regul. 2018, 9, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Council of State Boards of Nursing. A Global Profile of Nursing Regulation, Education, and Practice. J. Nurs. Regul. 2020, 10, 1–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKimm, J.; Newton, P.M.; Da Silva, A.; Campbell, J.; Condon, R.; Kafoa, B.; Kirition, R.; Roberts, G. Regulation and Licensing of Healthcare Professionals: A Review of International Trends and Current Approaches in Pacific Island Countries. 2012. Available online: https://sphcm.med.unsw.edu.au/sites/default/files/sphcm/Centres_and_Units/SI_licensing_Report.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Marchetti, A.; Virgolesi, M.; Pulimeno, A.M.; Rocco, G.; Stievano, A.; Venturini, G.; De Marinis, M.G. The licensure exam in nursing degree courses: A survey in the four universities of the Lazio Region. Ann. Ig. 2014, 26, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosqvist, K.; Koivisto, J.M.; Vierula, J.; Haavisto, E. Instruments used in graduating nursing students’ exit exams: An integrative review. Contemp. Nurse 2022, 58, 393–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humar, L.; Sansoni, J. Bologna Process and Basic Nursing Education in 21 European Countries. Ann. Ig. 2017, 29, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN). The Essentials: Core Competencies for Professional Nursing Education. Washington, DC: AACN; 2021. Available online: https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Publications/Essentials-2021.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Gobbi, M. A review of nurse educator career pathways: A European perspective. J. Res. Nurs. 2009, 14, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuning Educational Structures in Europe: Guidelines and Reference Points for the Design and Delivery of Degree Programmes in Nursing. 2018. Available online: https://www.calohee.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/1.4-Guidelines-and-Reference-Points-for-the-Design-and-Delivery-of-Degree-Programmes-in-Nursing-READER-v3.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Tuning Project: Nursing Specific Competences. 2012. Available online: https://www.unideusto.org/tuningeu/competences/ (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- European Federation of Nurses Associations. European Federation of Nurses Associations Guideline for the Implementation of Article 31 of the Mutual Recognition of Professional Qualifications Directive 2005/36/EC, Amended by Directive 2013/55/EU; Europe Federation Nurses Associations: Brussels, Belgium, 2015; Available online: https://efn.eu/?page_id=6897 (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Chappell, K.; Newhouse, R.; Lundmark, V.; ElChamaa, R.; Jeong, D.; Gallagher, D.K.; Salt, E.; Kitto, S. Methods of nursing certification in North America—A scoping review. Nurs. Outlook 2020, 68, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsman, H.; Jansson, I.; Leksell, J.; Lepp, M.; Sundin Andersson, C.; Engström, M.; Nilsson, J. Clusters of competence: Relationship between self-reported professional competence and achievement on a national examination among graduating nursing students. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The Job Demand–Resources Model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, J.L. Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence—From Domestic Abuse to Political Terror; Basic Books: New York, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almarwani, A.M. The effect of integrating a nursing licensure examination preparation course into a nursing program curriculum: A quasi-experimental study. Saudi J. Health Sci. 2022, 11, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amankwaa, I.; Agyemang-Dankwah, A.; Boateng, D. Previous education, sociodemographic characteristics, and nursing cumulative grade point average as predictors of success in nursing licensure examinations. Nurs. Res. Pract. 2015, 2015, 682479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athlin, E.; Larsson, M.; Söderhamn, O. A model for a national clinical final examination in the Swedish bachelor programme in nursing. J. Nurs. Manag. 2012, 20, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, C. Promoting quality in nursing education in Canada through a Canadian examination for baccalaureate nurses. Nurs. Leadersh. 2019, 32, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benefiel, D. Predictors of Success and Failure for ADN Students on the NCLEX-RN. Ph.D. Thesis, California State University, Fresno, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Efendi, F.; Nursalam, N.; Kurniati, A.; Gunawan, J. Nursing qualification and workforce for the Association of Southeast Asian Nations Economic Community. Nurs. Forum. 2018, 53, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatavicius, D.D. Preparing for the new nursing licensure exam: The next-generation NCLEX. Nursing 2021, 51, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilja Andersson, P.; Ahlner-Elmqvist, M.; Johansson, U.B.; Larsson, M.; Ziegert, K. Nursing students’ experiences of assessment by the Swedish National Clinical Final Examination. Nurse Educ. Today 2013, 33, 536–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Msibi, G.; Nkwanyana, N.; Kuebel, H. Eswatini Nursing Council Regulatory Reforms: Process towards Entry to Practice Examination. Ann. Glob. Health 2020, 86, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantaleo, F.; D’Angelo, D.; Stievano, A.; Albanesi, B.; Petrizzo, A.; Notarnicola, I.; De Marinis, M.G.; Marchetti, A. An example of evaluation of tuning nursing competences in the licensure exam: An observational study. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic, K.; Doyle, E.; Lane, A.; Corcoran, L. The work of preparing Canadian nurses for a licensure exam originating from the USA: A nurse educator’s journey into the institutional organization of the NCLEX-RN. Int. J. Nurs. Educ. Scholarsh. 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, A.D.; Lukewich, J.; Wells, J.; Kirkland, M.C.; Manuel, M.; Watkins, K. Identifying indicators of National Council Licensure Examination for Registered Nurses (NCLEX-RN) success in nursing graduates in Newfoundland & Labrador. Int. J. Nurs. Educ. Scholarsh. 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressler, J.L.; Kenner, C.A. Supporting student success on the NCLEX-RN. Nurse Educ. 2012, 37, 94–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, U.V. Regional Examination for Nurse Registration, Commonwealth Caribbean. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2000, 47, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, O. NCLEX Success First Attempt: An Exploratory Study of PassPoint and Comparative Analysis of Traditional Testing Versus Computerized Adaptive Testing. Ph.D. Thesis, William Carey University, Hattiesburg, MS, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Strube-Lahmann, S.; Vogler, C.; Friedrich, K.; Dassen, T.; Kottner, J. Zentral und dezentral verortete Prüfungen in der Krankenpflege. Vergleich der Abschlussnoten der Jahre 2008–2013 im Land Berlin unter Berücksichtigung unterschiedlicher Ausbildungskonzepte [Centrally and non-centrally designed exams in nursing: Comparisons of the final exams in 2008 to 2013 in Berlin focusing on different concepts of professional nursing education]. Z. Evidenz Fortbild. Qual. Gesundheitswesen 2016, 118–119, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, T.; Hariati, S.; Riskayani, F.; Djafar, M. International nurse licensure: Predictor factors associated with passing the Indonesian nurse competency examination. J. Nurs. Regul. 2021, 12, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendt, A.; Brown, P. The NCLEX examination: Preparing for future nursing practice. Nurse Educ. 2000, 25, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendt, A. Mapping geriatric nursing competencies to the 2001 NCLEX-RN test plan. Nurs. Outlook 2001, 51, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendt, A. The NCLEX-RN examination: Charting the course of nursing practice. Nurse Educ. 2003, 28, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendt, A.; Kenny, L. Monitoring entry-level practice: Keeping the National Council Licensure Examination for Registered Nurses current. Nurse Educ. 2007, 32, 78–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, M.K.; Shin, S. Using the Angoff method to set a standard on mock exams for the Korean nursing licensing examination. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2020, 17, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing (CASN). National Nursing Education Framework: Final Report. 2015. Available online: https://www.casn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/CASN-National-Education-Framwork-FINAL-2015.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Bloom, B.S. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals, 1st ed.; Longman Group: London, UK, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, G. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad. Med. 1990, 65 (Suppl. 9), 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.W.; Krathwohl, D.R. A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Complete Edition; Longman: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner, C.A. Thinking like a nurse: A research-based model of clinical judgment in nursing. J. Nurs. Educ. 2006, 45, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education. University and Research. The Framework of Italian Titles. Cycle Descriptors. 2012. Available online: https://www.cimea.it/EN/pagina-quadro-dei-titoli (accessed on 13 October 2022).

- Oermann, M.H.; Muckler, V.C.; Morgan, B. Framework for Teaching Psychomotor and Procedural Skills in Nursing. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2016, 47, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Quevedo, C.; Moreno-Casbas, M.T. Spain. In Strengthening Health Systems Through Nursing: Evidence from 14 European Countries; Rafferty, A.M., Ed.; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dolezel, J.; Zelenikova, R.; Finotto, S.; Mecugni, D.; Patelarou, A.; Panczyk, M.; Jarosova, D. Core evidence-based practice competencies and learning outcomes for European nurses: Consensus statements. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2021, 18, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, A.C.; Knebel, E. Chapter 3: The core competencies needed for health care professionals. In Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality; Greiner, A.C., Knebel, E., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; pp. 45–67. [Google Scholar]

- Gromer, A.L.; Patel, S.E.; Chesnut, S.R. Strategies for teaching psychomotor skills to undergraduate nursing students: A scoping review. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2025, 20, e98–e105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rukban, M.O. Guidelines for the construction of multiple choice questions tests. J. Fam. Community Med. 2006, 13, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillard, R.I. The Effects of Examinations and the Assessment Process on the Learning Activities of Undergraduate Medical Students. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Poorman, S.G.; Mastorovich, M.L. Constructing Next Generation National Council Licensure Examination (NCLEX) (NGN) style questions: Help for faculty. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2020, 15, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foronda, C.; MacWilliams, B.; McArthur, E. Interprofessional communication in healthcare: An integrative review. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2016, 19, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aebersold, M. Simulation-based learning: No longer a novelty in undergraduate education. Online J. Issues Nurs. 2018, 23, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).