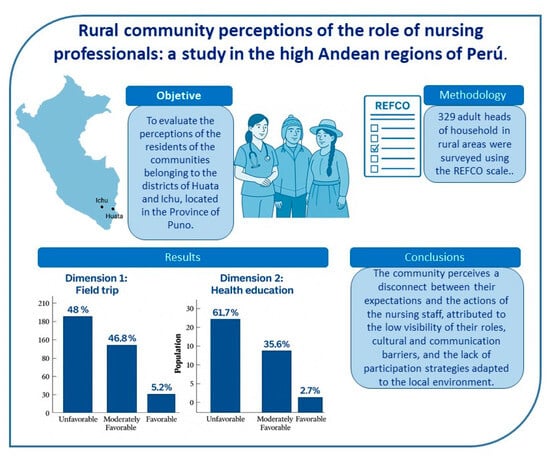

Perception of the Rural Community Regarding the Role of Nursing Professionals: A Study in the High Andean Regions of Peru

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Instrument for Measuring the Role of the Nursing Professional in the Community (REFCO)

2.2. Interview Procedure and Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Description

3.2. Population Perception on the Role of the Nursing Professional

3.3. Description of the Perception of the Residents Through Two Dimensions (Fieldwork and Health Education)

3.3.1. Description of Gender Perception (Fieldwork)

3.3.2. Description of Gender Perception (Health Education)

3.4. Multivariate Analysis of the Perception of the Role of the Nursing Professional

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- INIE Estado de La Población Peruana 2020. Available online: https://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/publicaciones_digitales/Est/Lib1743/Libro.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Carrillo-Larco, R.M.; Guzman-Vilca, W.C.; Leon-Velarde, F.; Bernabe-Ortiz, A.; Jimenez, M.M.; Penny, M.E.; Gianella, C.; Leguía, M.; Tsukayama, P.; Hartinger, S.M.; et al. Peru–Progress in Health and Sciences in 200 Years of Independence. Lancet Reg. Health-Am. 2022, 7, 100148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verulava, T. Access to Healthcare as a Fundamental Right or Privilege? Siriraj Med. J. 2021, 73, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MINSA. Informe de Evaluación de Implementación del Plan Estratégico Sectorial Multianual (PESEM). Available online: https://www.minsa.gob.pe/Recursos/OTRANS/05PlanEstrategico/Archivos/2023/IEI2016-2021-PESEM.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Gizaw, Z.; Astale, T.; Kassie, G.M. What Improves Access to Primary Healthcare Services in Rural Communities? A Systematic Review. BMC Prim. Care 2022, 23, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moises, A.; Prieto, R.; Zarate, V.; Cuba, M. Atributos de La Atencion Primaria de Salud: Una Vision Desde La Medicina Familiar. Acta Medica Peru. 2013, 30, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Cyr, M.E.; Etchin, A.G.; Guthrie, B.J.; Benneyan, J.C. Access to Specialty Healthcare in Urban versus Rural US Populations: A Systematic Literature Review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Giraldo, Á. The Role of Health Care Professionals in Primary Health Care (PHC). Rev. Fac. Nac. Salud Publica 2015, 33, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chasillacta, F.B.; Nuñez, F.R. Role of Nursing Personnel in Primary Health Care. Salud Cienc. y Tecnol. 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhlongo, E.M.; Lutge, E.; Adepeju, L. The Roles, Responsibilities and Perceptions of Community Health Workers and Ward-Based Primary Health Care Outreach Teams: A Scoping Review. Glob. Health Action 2020, 13, 1806526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girbés Fontana, M.; José Jurado Balbuena, J.; Rodríguez Escobar, J.; Esteban Paredes, F.; Luis Aréjula Torres, J.; Fontova Cemeli, T.; García Real, J.; Herrera García, M.; Primaria-Madrid, A. Enfermería En Atención Primaria: Nuestra Responsabilidad Con La Población (Experiencia Del Área 9). Rev. Adm. Sanit. 2005, 3, 49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Aliaga Rodríguez, G. “Rijcharismo” Movement in the Peruvian High Plateau as a Pioneer Intercultural Health Experience in the Americas. Rev. Cuba. Salud Publica 2015, 41, 497–509. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, D.S. Manuel Núñez Butrón: Pionero de La Atención Primaria En El Mundo. Rev. Med. Chile 2014, 142, 1612–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamani-Vilca, E.M.; Pelayo-Luis, I.P.; Guevara, A.T.; Sosa, J.V.C.; Carranza-Esteban, R.F.; Huancahuire-Vega, S. Validation of a Questionnaire That Measures Perceptions of the Role of Community Nursing Professionals in Peru. Aten. Primaria 2022, 54, 102194. [Google Scholar]

- Morán-Barrios, J. Assessment of Clinical Performance. Part 2. Questionaire, Design, Errors. Principles and Assessment Planning (Blueprint). Educ. Medica 2017, 18, 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, R.; Munro, J.; Evans, K.; Gaskin-Williams, A.; Hui, A.; Pearson, M.; Slade, M.; Kotera, Y.; Day, G.; Loughlin-Ridley, J.; et al. Health Service Improvement Using Positive Patient Feedback: Systematic Scoping Review. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0275045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rich, R.K.; Jimenez, F.E.; Bohacek, C.; Moore, A.; Heithoff, A.J.; Conley, D.M.; Brittin, J. The HDR CARE Scale, Inpatient Version: A Validated Survey Instrument to Measure Environmental Affordance for Nursing Tasks in Inpatient Healthcare Settings. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinker, T. A Technique for the Measurement of Attitudes. Arch. Psychol. 1932, 22, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Acosta-Salazar, D.; Lapeira-Panneflex, P.; Ramos-De La Cruz, E. Cuidado de Enfermería En La Salud Comunitaria. Duazary 2016, 13, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiño-Londoño, S.Y.; Mignone, J.; Castro, D.M.A.; Valencia, N.G.; Rojas Arbeláez, C.A. Guías Bilingües: Una Estrategia Para Disminuir Las Barreras Culturales En El Acceso y La Atención En Salud de Las Comunidades Wayuu de Maicao, Colombia. Salud Colect. 2016, 12, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hautecoeur, M.; Zunzunegui, M.V.; Vissandjee, B. Las Barreras de Acceso a Los Servicios de Salud En La Población Indígena de Rabinal En Guatemala. Salud Publica Mex. 2007, 49, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godsey, J.A.; Houghton, D.M.; Hayes, T. Registered Nurse Perceptions of Factors Contributing to the Inconsistent Brand Image of the Nursing Profession. Nurse Outlook 2020, 68, 808–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teresa-Morales, C.; Rodríguez-Pérez, M.; Araujo-Hernández, M.; Feria-Ramírez, C. Current Stereotypes Associated with Nursing and Nursing Professionals: An Integrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendezu-Quispe, G.; Mari-Huarache, L.F.; Taype-Rondan, Á.; Mejia, C.R.; Inga-Berrospi, F. Effect of Rural and Marginal Urban Health Service on the Physicians’ Perception of Primary Health Care in Peru. Rev. Peru. Med. Exp. Salud Publica 2020, 37, 636–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.; Vieira, I.; Pedro, M.; Caldas, P.; Varela, M. Patient Satisfaction with Healthcare Services and the Techniques Used for Its Assessment: A Systematic Literature Review and a Bibliometric Analysis. Healthc. Rev. 2023, 21, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco Cofre, J.A. Percepción Social de La Profesión de Enfermería. Enfermería Actual Costa Rica 2019, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, C.P.; Gallegos-Torres, R.M. The Role of the Nurse in Health Education. Horiz. Enferm. 2019, 30, 271–285. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Sarmiento, J.M.; Jaramillo-Jaramillo, L.I.; Villegas-Alzate, J.D.; Álvarez-Hernández, L.F.; Ruiz-Mejía, C. La Educación En Salud Como Una Importante Estrategia de Promoción y Prevención.Pdf. Arch. Med. 2020, 20, 490–504. [Google Scholar]

- Pineda, Y.; Zapata, P.; Vásquez, E. Impacto de La Cultura Organizacional En Las Instituciones de Salud Énfasis En La Seguridad Del Paciente. Una Revisión Sistemática. Nure Investig. 2022, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Grajales, R. La Gestión Del Cuidado de Enfermería. Index Enfermería 2004, 13, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Descriptions | f | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18 to 29 years | 81 | 24.6% |

| 30 to 59 years | 244 | 74.2% | |

| >60 years | 4 | 1.2% | |

| Total | 329 | 100.0% | |

| Gender | Female | 180 | 54.7% |

| Male | 149 | 45.3% | |

| Total | 329 | 100.0% | |

| Level of Education | Incomplete primary | 43 | 13.1% |

| Complete primary | 54 | 16.4% | |

| Incomplete secondary | 50 | 15.2% | |

| Complete secondary | 121 | 36.8% | |

| Incomplete Superior | 38 | 11.6% | |

| Complete Superior | 23 | 7.0% | |

| Total | 329 | 100.0% | |

| Occupation | Farmer | 61 | 18.5% |

| Bricklayer | 29 | 8.8% | |

| Housewife | 89 | 27.1% | |

| Driver | 3 | 0.9% | |

| Merchant | 33 | 10.0% | |

| Student | 27 | 8.2% | |

| Livestock Farmer | 67 | 20.4% | |

| Professional | 11 | 3.3% | |

| Technician | 9 | 2.7% | |

| Total | 329 | 100.0% | |

| Areas | Huata—1° Collana | 197 | 59.9% |

| Ichu—estación | 42 | 12.8% | |

| Ichu—Checarmaya | 6 | 1.8% | |

| Ichu—Tunuhuire grande | 44 | 13.4% | |

| Ichu—Tunuhuire chico | 40 | 12.2% | |

| Total | 329 | 100.0% | |

| Years of residence | 1 to 9 years | 50 | 15.2% |

| 10 to 19 years | 50 | 15.2% | |

| 20 to 29 years | 75 | 22.8% | |

| >30 years | 154 | 46.8% | |

| Total | 329 | 100.0% | |

| f | % | |

| Unfavorable | 178 | 54.1% |

| Moderately favorable | 145 | 44.1% |

| Favorable | 6 | 1.8% |

| Unfavorable | 329 | 100.0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rocha Zapana, N.M.; Maquera Bernedo, E.G.; Mamani Zapana, W.H.; Esteves Villanueva, A.R.; Ramos Calisaya, N.G. Perception of the Rural Community Regarding the Role of Nursing Professionals: A Study in the High Andean Regions of Peru. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15050148

Rocha Zapana NM, Maquera Bernedo EG, Mamani Zapana WH, Esteves Villanueva AR, Ramos Calisaya NG. Perception of the Rural Community Regarding the Role of Nursing Professionals: A Study in the High Andean Regions of Peru. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(5):148. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15050148

Chicago/Turabian StyleRocha Zapana, Nelly Martha, Elsa Gabriela Maquera Bernedo, William Harold Mamani Zapana, Angela Rosario Esteves Villanueva, and Nury Gloria Ramos Calisaya. 2025. "Perception of the Rural Community Regarding the Role of Nursing Professionals: A Study in the High Andean Regions of Peru" Nursing Reports 15, no. 5: 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15050148

APA StyleRocha Zapana, N. M., Maquera Bernedo, E. G., Mamani Zapana, W. H., Esteves Villanueva, A. R., & Ramos Calisaya, N. G. (2025). Perception of the Rural Community Regarding the Role of Nursing Professionals: A Study in the High Andean Regions of Peru. Nursing Reports, 15(5), 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15050148