Comfort and Person-Centered Care: Adaptation and Validation of the Colcaba-32 Scale in the Context of Emergency Services

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Target Population and Sample

2.4. Application Procedures

2.5. Statistical Treatment

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Suitability of the Sample for Factor Analysis

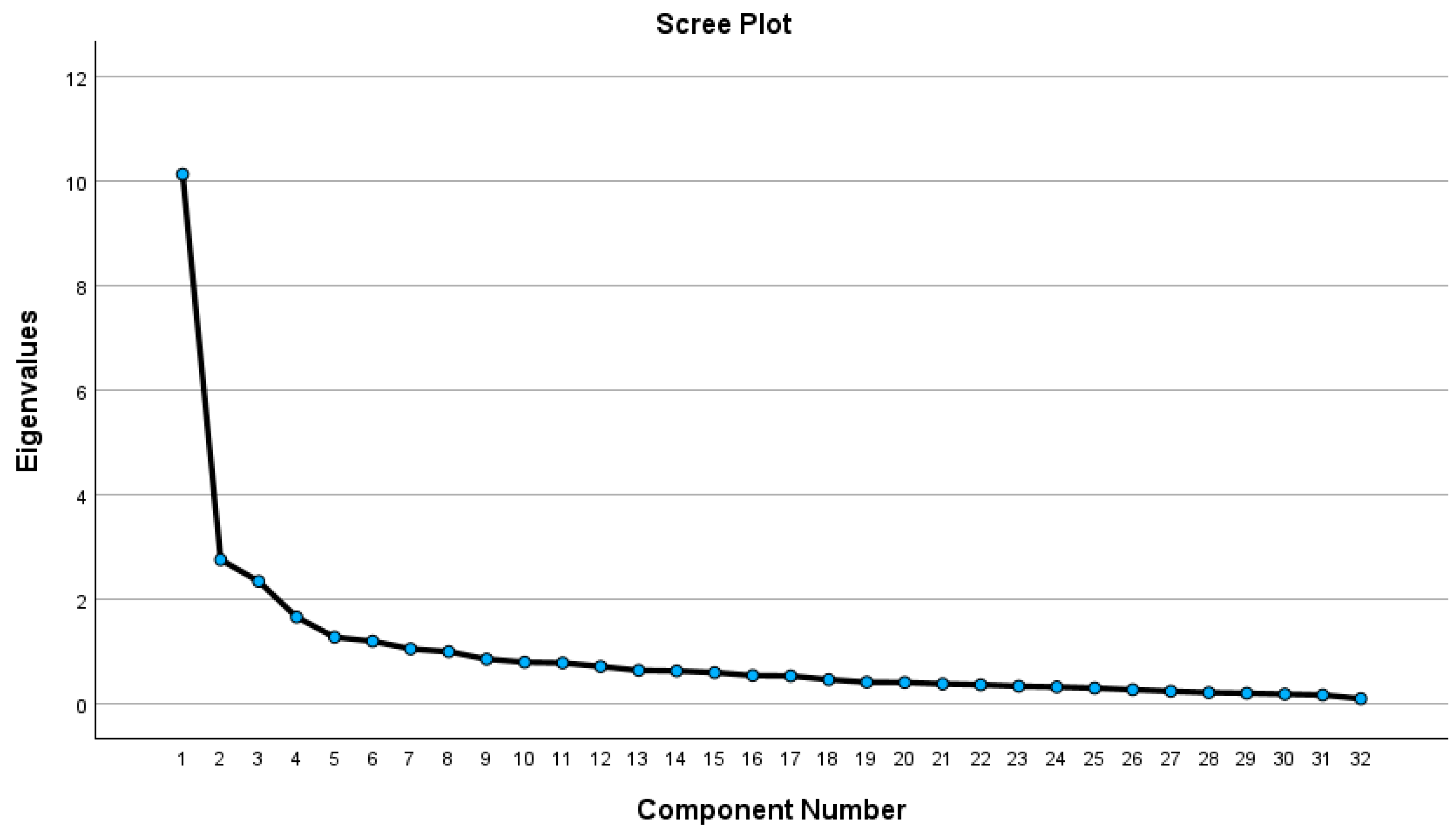

3.2. Principal Component Analysis

3.3. Identified Factor Structure

3.4. Descriptive Statistics of the Dimensions

3.5. Internal Consistency

3.6. Correlations Between the Dimensions of the COLCABA-32 Scale and the Structural Consistency of the Instrument

3.7. Convergent and Divergent Validity

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MMSE | Mini-Mental State Examination |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| GCQ | General Comfort Questionnaire |

| COSMIN | Consensus-based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments |

| CVI | Content Validity Index |

| KMO | Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin |

References

- Nightngale, F.; Ferraz Germano, C.C. Notas Sobre a Enfermagem: O Que é e o Que não é. 2005, 201. Available online: https://books.google.pt/books/about/NOTAS_SOBRE_ENFERMAGEM.html?id=_wIyEAAAQBAJ&redir_esc=y (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Goes, M.; Oliveira, H.; Lopes, M.; Fonseca, C.; Pinho, L. Satisfaction: A Concept Based on Functionality and Quality of Life to Be Integrated in a Nursing Care Performance System. In International Workshop on Gerontechnology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comfort Theory and Practice: A Vision for Holistic Health Care and Research—Katharine Kolcaba—Google Livros. Available online: https://books.google.pt/books/about/Comfort_Theory_and_Practice.html?id=nduGie_ouQkC&redir_esc=y (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Kum, K.M.; Bi, M.; Atanga, S.; Landis, F.; Celestin, N.; Kelvin, M.K. Comfort Measures in Patients with Traumatic Injuries: A Systematic Review. Glob. J. Emerg. Crit. Care Med. 2025, 2, 1–7. Available online: https://www.scivisionpub.com/pdfs/comfort-measures-in-patients-with-traumatic-injuries-a-systematic-review-3889.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Aloustani, S.; Parsai, M.; Siyasari, A.R.; Sharifi Rizi, M.; Papi, S.; Zafarramazanian, F. Applications of Kolcaba’s Comfort Theory to improve nursing practice: A narrative review. J. Nurs. Rep. Clin. Pract. 2025, 4, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Baz, M.D.; Pacheco-Del Cerro, E.; Durango-Limárquez, M.I.; Alcantarilla-Martín, A.; Romero-Arribas, R.; Ledesma-Fajardo, J.; Moro-Tejedor, M.N. The comfort perception in the critically ill patient from the Kolcaba theoretical model. Enfermería Intensiv. 2024, 35, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Baz, M.D.; Del Cerro, E.P.; Ferrer-Ferrándiz, E.; Araque-Criado, I.; Merchán-Arjona, R.; de la Rubia Gonzalez, T.; Tejedor, M.N.M. Psychometric validation of the Kolcaba General Comfort Questionnaire in critically ill patients. Aust. Crit. Care 2023, 36, 1025–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, E.; Sousa, P.P.; Marques, R.M.D. Marques, Comfort in the emergency service: The experience of families of critically ill patients. Rev. Enferm. Ref. 2022, 6, e21118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Azevedo Ponte, K.M.; Bastos, F.E.S.; Fontenele, M.G.M.; de Sousa, J.G.; Aragão, O.C. Comfort requirements of patients assisted by the urgency and emergency service: Implications for the nursing profession/Necessidades de conforto de pacientes atendidos no serviço de urgência e emergência: Implicações para enfermagem. Rev. Pesqui. Cuid. é Fundam. Online 2019, 11, 925–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, C. Physical Examination and Health Assessment/Carolyn Jarvis, Ann Eckhardt; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, E.; Özakgül, A. The effect of nursing care based on Comfort Theory of Kolcaba on comfort, satisfaction and sleep quality of intensive care patients. Nurs. Crit. Care 2025, 30, e70033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, K. Creating a Healing Environment. Holist. Nurs. Pract. 2025, 39, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourão Nicoli, E.; Valéria Costa e Silva, F.; Pereira Caldas, C.; Guimarães Assad, L.; Feio da Maia Lima, C.; Marinho Chrizostimo, M. Management of care for hospitalized older persons—Comfort as an essential outcome: A qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, R.; Oliveira, H.; Goes, M.; Gonçalves, C.; Dias, A.; Fonseca, C. The Effectiveness of Nursing Rehabilitation Interventions on Self-Care for Older Adults with Respiratory Disorders: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocak, U.; Avsarogullari, L. Expectations and needs of relatives of critically ill patients in the emergency department. Hong Kong J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 26, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.E.; Gandek, B. Methods for testing data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability: The IQOLA Project approach. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1998, 51, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gümüştekin, K.; Özyer Güvener, Y. The Effect of Comfort Theory-Based Nursing Care on Intolerance of Uncertainty and Comfort Levels in Individuals Undergoing Hemodialysis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Res. Theory Nurs. Pract. 2025, 39, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolcaba, K. Teoría y Práctica del Confort: Una Visión Para la Atención Sanitaria y la Investigación Holísticas; Springer Publishing Company: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; p. 264. [Google Scholar]

- Kolcaba, K.Y. A theory of holistic comfort for nursing. J. Adv. Nurs. 1994, 19, 1178–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandão, M.A.G.; Martins, J.S.D.A.; Peixoto, M.D.A.P.; Lopes, R.O.P.; Primo, C.C. Theoretical and methodological reflections for the construction of middle-range nursing theories. Texto E Contexto Enferm. 2017, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kolcaba, K. Evolution of the mid range theory of comfort for outcomes research. Nurs. Outlook 2001, 49, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dayse e Silva, A.; e Souza Nascimento, S. Teoria do conforto de Kolcaba no cuidado de enfermagem: Uma revisão integrativa. Rev. JRG De Estud. Acadêmicos 2023, VI, 946–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, R.B.; Caldas, C.P.; Souza, P.A.D. Nursing Activities score e sua correlação com a teoria do conforto de kolcaba: Reflexão teórica. Enferm. Foco 2019, 10, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goes, M.; Oliveira, H.; Lopes, M.; Fonseca, C.; Pinho, L.; Marques, M. A nursing care-sensitive patient satisfaction measure in older patients. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnier, J.J.; Lai, J.; Mokkink, L.B.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN reporting guideline for studies on measurement properties of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual. Life Res. 2021, 30, 2197–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM)An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroco, J.; Garcia-Marques, T. Qual a fiabilidade do alfa de Cronbach? Questões antigas e soluções modernas? Laboratório Psicol. 2006, 4, 65–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marôco, J. Análise Estatística com o SPSS Statistics, 7th ed.; ReportNumber, Lda; Gráfica Manuel Barbosa & Filhos: Pêro Pinheiro, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yuswanto, T.J.A.; Wahendra, D.D.; Marsaid, M.; Anjaswarni, T. According to Kolcaba’s theory comfort increases the peace of mind of operating room nurses. J. Keperawatan 2025, 16, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pestana, H.; Gageiro, J. Análise de Dados Para Ciências Sociais. Edições Sílabo 2014, 6, 1240. Available online: https://silabo.pt/catalogo/informatica/aplicativos-estatisticos/livro/analise-de-dados-para-ciencias-sociais (accessed on 11 September 2025).

| Variable | Category | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 67 | 40.6 |

| Female | 98 | 59.4 | |

| Age groups | 18–29 | 25 | 15.2 |

| 30–39 | 25 | 15.2 | |

| 40–49 | 22 | 13.3 | |

| 50–59 | 31 | 18.8 | |

| 60–69 | 38 | 23 | |

| 70–79 | 25 | 15.2 | |

| 80–89 years old | 9 | 5.5 | |

| Education | Primary | 57 | 34.5 |

| Basic education | 43 | 26.1 | |

| Secondary Education | 59 | 35.8 | |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 5 | 3.0 | |

| Master’s degree | 1 | 0.6 | |

| First time in the emergency room? | Yes | 4 | 2.4 |

| No | 161 | 97.6 | |

| Manchester Triage | Orange | 52 | 31.5 |

| Yellow | 58 | 35.2 | |

| Green | 55 | 33.3 |

| KMO Measure (Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin of Sample Adequacy) | 0.879 | |

|---|---|---|

| Bartlett’s test (Sphericity test) | Chi-square | 2716.646 |

| Df | 496 | |

| Sig. | <0.001 | |

| Items | Eigenvalue | % Variance | % Variance Accumulated | Amount Own | % Variance | % Variance Accumulated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10.145 | 31.704 | 31.704 | 4.999 | 15.621 | 15.621 |

| 2 | 2.763 | 8.634 | 40.338 | 4.887 | 15.272 | 30.893 |

| 3 | 2.349 | 7.342 | 47.680 | 2.673 | 8.352 | 39.245 |

| 4 | 1.664 | 5.199 | 52.880 | 2.401 | 7.504 | 46.749 |

| 5 | 1.279 | 3.995 | 56.875 | 2.338 | 7.305 | 54.054 |

| 6 | 1.203 | 3.758 | 60.633 | 1.586 | 4.956 | 59.010 |

| Items | Factors | h2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| Psycho-emotional and Autonomy | |||||||

| 28—I feel out of control (reversed) | 0.761 | 0.691 | |||||

| P29—I feel uncomfortable because I am not dressed (reversed) | 0.759 | 0.663 | |||||

| P5—I feel dependent on others (Reversed) | 0.724 | 0.713 | |||||

| P24—My belongings are not here (Reversed) | 0.649 | 0.742 | |||||

| P12—I am constipated at the moment (Reversed) | 0.637 | 0.638 | |||||

| P7—No one understands me (Reversed) | 0.625 | 0.552 | |||||

| P4—I feel confident. | 0.589 | 0.582 | |||||

| P20—I am very tired (Reversed) | 0.520 | 0.609 | |||||

| Physical and Symptomatic | |||||||

| P13—I don’t feel healthy right now (Reversed) | 0.757 | 0.726 | |||||

| P3—My health makes me sad (Reversed) | 0.755 | 0.723 | |||||

| P6—Noise prevents me from resting (Reversed) | 0.687 | 0.632 | |||||

| P8—My pain is difficult to bear (Reversed) | 0.638 | 0.700 | |||||

| P23—This chair/bed hurts me (Reversed) | 0.625 | 0.687 | |||||

| P1—I have enough privacy | 0.588 | 0.689 | |||||

| P15—I am afraid of what is about to happen (Reversed) | 0.544 | 0.740 | |||||

| Relational and Information | |||||||

| P27—I need to be better informed about my health status (Reversed) | 0.791 | 0.648 | |||||

| P18—I would like to see my doctor more often (Reversed) | 0.783 | 0.712 | |||||

| Spiritual | |||||||

| P10—My faith helps me not to be afraid | 0.908 | 0.863 | |||||

| P26—My beliefs give me peace of mind | 0.906 | 0.883 | |||||

| Environmental | |||||||

| P11—I don’t like this place (Reversed) | 0.737 | 0.577 | |||||

| P19—The temperature in this place is pleasant | 0.649 | 0.673 | |||||

| Motivational and Hope | |||||||

| P32—I need to feel good again (Reversed) | 0.741 | 0.698 | |||||

| P22—The mood here makes me feel better | 0.514 | 0.665 | |||||

| COLCABA-32 Dimension | Mean | Deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psycho-emotional and Autonomy | 2.94 | 0.58 | 1.63 | 4.0 |

| Physical and Symptomatic | 2.16 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 3.86 |

| Relational and Information | 1.97 | 0.61 | 1.00 | 4.0 |

| Spiritual | 2.91 | 0.66 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Environmental | 2.28 | 0.52 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Motivation and Hope | 1.98 | 0.35 | 1.00 | 2.50 |

| Factors | Items | Item–total Correlation |

|---|---|---|

| Factor I—Psycho-emotional Comfort and Autonomy Cronbach’s alpha = 0.865 Spearman–Brown = 0.712/0.832 | 28 | 0.702 |

| 29 | 0.690 | |

| 5 | 0.715 | |

| 24 | 0.559 | |

| 12 | 0.492 | |

| 7 | 0.574 | |

| 4 | 0.612 | |

| 20 | 0.598 | |

| Factor II—Physical and Symptomatic Comfort Cronbach’s alpha = 0.887 Spearman–Brown = 0.873/0.875 | 13 | 0.725 |

| 3 | 0.599 | |

| 6 | 0.683 | |

| 8 | 0.707 | |

| 23 | 0.694 | |

| 1 | 0.633 | |

| 15 | 0.722 | |

| Factor III—Relational Comfort and Information Cronbach’s alpha = 0.703 Spearman–Brown = 0.703 | 27 | 0.542 |

| 18 | 0.542 | |

| Factor IV—Spiritual Comfort Cronbach’s alpha = 0.914 Spearman–Brown = 0.914 | 10 | 0.842 |

| 26 | 0.842 | |

| Factor V—Environmental Comfort Cronbach’s alpha = 0.600 Spearman–Brown = 0.600 | 11 | 0.384 |

| 19 | 0.384 | |

| Factor VI—Motivational Comfort and Hope Cronbach’s alpha = 0.758 Spearman–Brown = 0.759 | 32 | 0.284 |

| 22 | 0.284 |

| Psycho-emotional and Autonomy | Physical and Symptomatic | Relational Information | Spiritual | Environmental | Motivational and Hope | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colcaba Total Scale | r | 0.813 ** | 0.916 ** | 0.425 ** | −0.125 | 0.564 ** | 0.569 ** |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.110 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Psycho-emotional and Autonomy | r | 1.000 | 0.651 ** | 0.181 * | −0.221 ** | 0.261 ** | 0.396 ** |

| p | ----- | <0.001 | 0.020 | 0.004 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Physical and Symptomatic | r | 0.651 ** | 1.000 | 0.345 ** | −0.202 ** | 0.486 ** | 0.489 ** |

| p | <0.001 | ----- | <0.001 | 0.009 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Relational and Information | r | 0.181 * | 0.345 ** | 1.000 | −0.134 | 0.356 ** | 0.173 * |

| p | 0.020 | <0.001 | ----- | 0.086 | <0.001 | 0.026 | |

| Spiritual | r | −0.221 ** | −0.202 ** | −0.134 | 1.000 | 0.053 | −0.074 |

| p | 0.004 | 0.009 | 0.086 | ----- | 0.497 | 0.342 | |

| Environmental | r | 0.261 ** | 0.486 ** | 0.356 ** | 0.053 | 1.000 | 0.454 ** |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.497 | ----- | <0.001 | |

| Motivational and Hope | r | 0.396 ** | 0.489 ** | 0.173 * | −0.074 | 0.454 ** | 1.000 |

| p | <0.001 | 0.916 ** | 0.026 | 0.342 | <0.001 | ----- | |

| COLCABA-32 Dimensions | Manchester Triage | |

|---|---|---|

| Psycho-emotional comfort and autonomy | r | 0.452 ** |

| p | <0.001 | |

| Physical and Symptomatic Comfort | r | 0.740 ** |

| p | <0.001 | |

| Relational Comfort and Information | r | 0.140 |

| p | 0.074 | |

| Spiritual Comfort | r | −0.124 |

| p | 0.113 | |

| Environmental Comfort | r | 0.309 ** |

| p | <0.001 | |

| Motivational Comfort and Hope | r | 0.318 ** |

| p | <0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marques, M.d.C.; Goes, M.; João, A.; Oliveira, H.; Mendes, C.; Pires, R.; Bravo, N. Comfort and Person-Centered Care: Adaptation and Validation of the Colcaba-32 Scale in the Context of Emergency Services. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110383

Marques MdC, Goes M, João A, Oliveira H, Mendes C, Pires R, Bravo N. Comfort and Person-Centered Care: Adaptation and Validation of the Colcaba-32 Scale in the Context of Emergency Services. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(11):383. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110383

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarques, Maria do Céu, Margarida Goes, Ana João, Henrique Oliveira, Cláudia Mendes, Rute Pires, and Nuno Bravo. 2025. "Comfort and Person-Centered Care: Adaptation and Validation of the Colcaba-32 Scale in the Context of Emergency Services" Nursing Reports 15, no. 11: 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110383

APA StyleMarques, M. d. C., Goes, M., João, A., Oliveira, H., Mendes, C., Pires, R., & Bravo, N. (2025). Comfort and Person-Centered Care: Adaptation and Validation of the Colcaba-32 Scale in the Context of Emergency Services. Nursing Reports, 15(11), 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110383