Healthcare Professionals’ Perceptions of Anhedonia in Major Depressive Disorder and the Possibilities of Episodic Future Thinking Training: A Qualitative Study in a Tertiary Care Hospital

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Researcher Role

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Participants

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Data Analysis

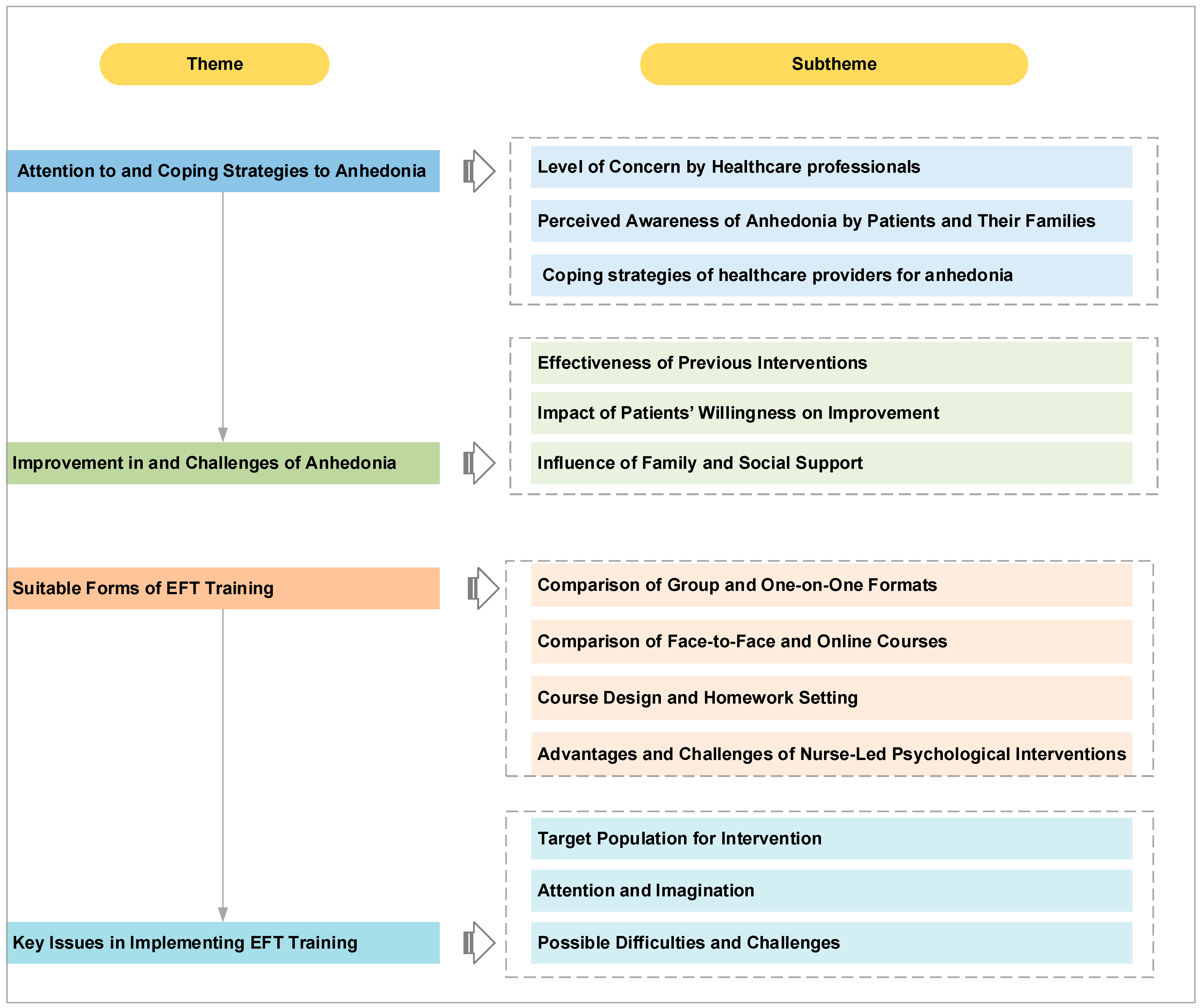

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data

3.2. Interview Results

3.2.1. Attention to and Responses to Anhedonia

Level of Concern by Healthcare Professionals

Anhedonia is very common in depression patients; we have assessed over 1000 cases, and about 70–80% * of these patients exhibit this symptom.(N8 Doctor)

From my observation, anhedonia is quite severe in patients. When we assess or diagnose MDD, anhedonia is one of the key symptoms—patients often lose interest in many things.(N14 Psychological Counselor)

When we conduct psychotherapy, the focus is more on uncovering the irrational beliefs. As for symptoms like anhedonia, they are common, but less often addressed directly.(N15 Psychotherapist)

In clinical practice, we don’t assess anhedonia specifically. We may look at whether a patient has lost hope for the future, which overlaps with anhedonia. But our main focus remains on evaluating risk.(N5 Head Nurse)

* Note: These figures reflect clinicians’ subjective perceptions based on their professional experience, rather than epidemiological data.

Perceived Awareness of Anhedonia by Patients and Their Families

Many patients and families have poor awareness of anhedonia. This lack of understanding can hinder their recovery.(N5 Head Nurse)

Many patients, including their families, fail to recognize that losing interest or hope for the future is actually anhedonia.(N6 Head Nurse)

For patients with MDD, they may experience happy events but suppress their feelings, not acknowledging or enjoying the happiness.(N8 Doctor)

Coping Strategies of Healthcare Providers for Anhedonia

In clinical practice, we primarily use medication. After stabilizing the patient’s condition, we provide some psychological counseling and interventions.(N8 Doctor)

I use hypnosis therapy, which is quite different from standard psychotherapy.(N11Psychological Counselor)

I use narrative therapy to understand when and why the patient lost their ability to experience pleasure.(N14 Psychological Counselor)

3.2.2. Improvement in and Challenges of Anhedonia

Effectiveness of Previous Interventions

The improvement is modest—on a scale where 0 is neutral, patients might score 4 or 5, indicating a slight sense of pleasure.(N14 Psychological Counselor)

The effects are variable. If a patient has strong family support, they may recover from anhedonia more effectively, but about 1/3 to half of patients will still have residual symptoms.(N8 Doctor)

Medication can control symptoms in the short term, but long-term improvement requires a shift in cognition.(N14 Psychological Counselor)

Impact of Patients’ Willingness on Improvement

Whether any treatment succeeds depends on the patient’s willingness to cooperate and their mental flexibility.(N15 Psychotherapist)

It depends on the individual’s willingness. If they have a strong desire to change, improvement can happen quickly. Otherwise, the outcome is poor.(N12Psychological Counselor)

Patients with strong motivation improve more quickly. However, most depression patients have low energy and are resistant to change, so their progress is slower.(N12 Psychological Counselor)

Influence of Family and Social Support

Patients with MDD feel very empty inside, and family support helps improve their condition over time.(N13 Psychological Counselor)

Family and social support can facilitate recovery.(N8 Doctor)

Family support, social support; that is conducive to his condition.(N10Psychological Counselor)

Some patients are hospitalized for MDD, but if their family doesn’t acknowledge the problem, their recovery is slower. Even after recovery, returning to a non-supportive family environment can destabilize their condition.(N8 Doctor)

3.2.3. Suitable Forms of EFT Training

Comparison of Group and One-on-One Formats

The advantage of group therapy is that it improves efficiency, and it simulates a relatively real environment.(N15 Psychotherapist)

Group therapy is generally more difficult because many patients here have emotional problems.(N15 Psychotherapist)

I think the effect of group therapy should be similar to one-on-one, as long as the group therapy is conducted continuously according to the treatment plan.(N12Psychological Counselor)

In a group setting, everyone listens, but they may not be very open to discussing deeper personal issues, as some things need to be kept confidential.(N10Psychological Counselor)

Comparison of Face-to-Face and Online Courses

Online psychological therapy is possible, as long as the patient cooperates. During the pandemic, for example, if the therapist couldn’t come or if patients couldn’t go out, the therapist would add them on WeChat and conduct video consultations.(N2 Nurse)

I think online courses are feasible. Some patients find it inconvenient to come to the hospital, so they receive online consultations and discuss their symptoms online, and they are quite willing to cooperate.(N8 Doctor)

Previously, face-to-face consultations were emphasized, where one-on-one interaction allowed for judgment based on the patient’s expressions and tone. However, for depression patients, it’s difficult to get them to come for consultations because they don’t want to leave their homes. Online interventions can still be effective.(N12Psychological Counselor)

Generally speaking, since our patients are hospitalized for short periods, it’s fine to conduct the later sessions online, as long as trust is established with the patient in the early stages.(N13Psychological Counselor)

Course Design and Homework Setting

I think, based on the hospitalization period, a routine frequency of 1–2 sessions per week and a total of 4–6 sessions would be appropriate.(N3 Nurse)

Depressed patients generally have less desire to express themselves; some may not want to speak. Our group therapy sessions typically last 50 min to an hour.(N2 Nurse)

I believe that unless the content is extremely engaging and stimulates patients’ willingness to express themselves, the course may feel short or too long, and the patient may lose interest.(N3 Nurse)

For mild patients, 4–6 sessions can be very effective. It can address urgent issues and provide immediate relief.(N10Psychological Counselor)

Here, patients usually have short hospitalization times, so about three sessions of psychological therapy is typical, while more severe cases might require about four.(N15 Psychotherapist)

We will remind patients about homework repeatedly, but we shouldn’t treat it as an assignment. If it’s treated as an assignment, they may refuse to do it.(N12 Psychological Counselor)

We generally suggest [that] the patient do the homework, but we don’t force them. Next time, we’ll discuss their progress with them.(N13Psychologist)

For our patients, homework is not highly valued, as depression patients often have low motivation.(N1 Nurse)

Advantages and Challenges of Nurse-Led Psychological Interventions

Nurse-led interventions are definitely effective. Some patients may not seek help from psychological professionals, but instead go to doctors or nurses.(N11Psychological Counselor)

In clinical practice, if nurses have good communication skills, rich experience, professional knowledge, and qualifications, they can lead psychological interventions.(N1 Nurse)

When nurses lead psychological interventions, they need to find a balance between compassion and professionalism. The most important ethical boundary is having a conscience and compassion. Technical knowledge is also crucial, as they need to understand the patient’s needs and how to address them.(N11Psychological Counselor)

Nurses leading psychological interventions may experience emotional and cognitive challenges. They need time to adjust. For example, nurses who provide psychological therapy in our department receive regular professional counseling to maintain emotional stability.(N5 Head Nurse)

3.2.4. Key Issues in Implementing EFT Training

Target Population for Intervention

We should add exclusion criteria during the screening process, such as severely negative or suicidal patients, or those on heavy psychiatric medications.(N5 Head Nurse)

You can choose younger patients for intervention, as they are more cooperative. Older patients may become impatient and less cooperative during treatment.(N2 Nurse)

Patients should be selected based on their condition, focusing on those whose emotions are stable.(N1 Nurse)

Attention and Imagination

Attention is a big problem for patients, and their ability to imagine is also crucial. Since this training involves constructing future scenarios, you need to first build their ability to imagine before the training can lead to significant improvement.(N8 Doctor)

This requires engaging the patient’s attention, especially their imagination.(N13Psychological Counselor)

We generally assess patients with MDD in two ways: first, their attention, as without it they will not be able to continue the training. Second, we assess their imagination. Many patients with MDD find it difficult to imagine. If their attention and imagination are both good, they will definitely be able to learn. If either is lacking, it will be difficult for them to imagine.(N12Psychological Counselor)

Possible Difficulties and Challenges

Some of these patients are not very cooperative; some come just because their parents asked them to. They come to chat, and you could do 10 sessions with them, but I think it won’t be of much use. If you want this to be effective, the first thing you need is a good therapeutic relationship; this is extremely important.(N15 Psychotherapist)

During the imagination process, they might think of some negative things. So when guiding them, it is essential to have a professional psychological counselor nearby. If the patient suddenly experiences negative emotions, they can help bring the patient back.(N2 Nurse)

People feel safer in familiar environments. If the members are more fixed, there’s an established rapport and trust. With trust comes safety, and only then can they fully invest in the treatment.(N14 Psychological Counselor)

Some people are slow to warm up, and it may take a long time for them to integrate. Others may be unwilling to cooperate.(N15 Psychotherapist)

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vos, T.; Lim, S.S.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi, M.; Abbasifard, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Depressive Disorder (Depression). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Zhao, H.; Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Shi, J.; Lai, W.; Wang, W.; Guo, L.; Gong, J.; Lu, C. Global, regional, and national burden of depressive disorders among young people aged 10–24 years, 2010–2019. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2024, 170, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Yu, X.; Yan, J.; Yu, Y.; Kou, C.; Xu, X.; Lu, J.; et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in China: A cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, A.J.; Santomauro, D.F.; Aali, A.; Abate, Y.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd ElHafeez, S.; Abdelmasseh, M.; Abd-Elsalam, S.; Abdollahi, A.; et al. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2133–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treadway, M.T.; Zald, D.H. Reconsidering anhedonia in depression: Lessons from translational neuroscience. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2011, 35, 537–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rømer Thomsen, K.; Whybrow, P.C.; Kringelbach, M.L. Reconceptualizing anhedonia: Novel perspectives on balancing the pleasure networks in the human brain. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelizza, L.; Ferrari, A. Anhedonia in schizophrenia and major depression: State or trait? Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2009, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franken, I.H.A.; Rassin, E.; Muris, P. The assessment of anhedonia in clinical and non-clinical populations: Further validation of the Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale (SHAPS). J. Affect. Disord. 2007, 99, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckner, J.D.; Joiner, T.E.J.; Pettit, J.W.; Lewinsohn, P.M.; Schmidt, N.B. Implications of the DSM’s emphasis on sadness and anhedonia in major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2008, 159, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baune, B.T.; Florea, I.; Ebert, B.; Touya, M.; Ettrup, A.; Hadi, M.; Ren, H. Patient Expectations and Experiences of Antidepressant Therapy for Major Depressive Disorder: A Qualitative Study. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2021, 17, 2995–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawes, M.; Galynker, I.; Barzilay, S.; Yaseen, Z.S. Anhedonia and suicidal thoughts and behaviors in psychiatric outpatients: The role of acuity. Depress. Anxiety 2018, 35, 1218–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winer, E.S.; Nadorff, M.R.; Ellis, T.E.; Allen, J.G.; Herrera, S.; Salem, T. Anhedonia predicts suicidal ideation in a large psychiatric inpatient sample. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 218, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metts, A.V.; Echiverri-Cohen, A.M.; Yarrington, J.S.; Zinbarg, R.E.; Mineka, S.; Craske, M.G. Longitudinal associations among dimensional symptoms of depression and anxiety and first onset suicidal ideation in adolescents. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2023, 53, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducasse, D.; Loas, G.; Dassa, D.; Gramaglia, C.; Zeppegno, P.; Guillaume, S.; Olié, E.; Courtet, P. Anhedonia is associated with suicidal ideation independently of depression: A meta-analysis. Depress. Anxiety 2018, 35, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinckier, F.; Gourion, D.; Mouchabac, S. Anhedonia predicts poor psychosocial functioning: Results from a large cohort of patients treated for major depressive disorder by general practitioners. Eur. Psychiatry 2017, 44, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uher, R.; Perlis, R.H.; Henigsberg, N.; Zobel, A.; Rietschel, M.; Mors, O.; Hauser, J.; Dernovsek, M.Z.; Souery, D.; Bajs, M.; et al. Depression symptom dimensions as predictors of antidepressant treatment outcome: Replicable evidence for interest-activity symptoms. Psychol. Med. 2012, 42, 967–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutt, D.; Demyttenaere, K.; Janka, Z.; Aarre, T.; Bourin, M.; Canonico, P.L.; Carrasco, J.L.; Stahl, S. The other face of depression, reduced positive affect: The role of catecholamines in causation and cure. J. Psychopharmacol. 2007, 21, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuijpers, P.; Karyotaki, E.; Weitz, E.; Andersson, G.; Hollon, S.D.; van Straten, A. The effects of psychotherapies for major depression in adults on remission, recovery and improvement: A meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 159, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boumparis, N.; Karyotaki, E.; Kleiboer, A.; Hofmann, S.G.; Cuijpers, P. The effect of psychotherapeutic interventions on positive and negative affect in depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 202, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, C.T.; Lyubomirsky, S.; Stein, M.B. Upregulating the positive affect system in anxiety and depression: Outcomes of a positive activity intervention. Depress. Anxiety 2017, 34, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, J.; Riggs, K.J.; Anderson, R.J. A brighter future: The effect of positive episodic simulation on future predictions in non-depressed, moderately dysphoric & highly dysphoric individuals. Behav. Res. Ther. 2018, 100, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallford, D.J.; Barry, T.J.; Austin, D.W.; Raes, F.; Takano, K.; Klein, B. Impairments in episodic future thinking for positive events and anticipatory pleasure in major depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 260, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rösch, S.A.; Stramaccia, D.F.; Benoit, R.G. Promoting farsighted decisions via episodic future thinking: A meta-analysis. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2022, 151, 1606–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallford, D.J.; Rusanov, D.; Yeow, J.J.E.; Austin, D.W.; D’Argembeau, A.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M.; Raes, F. Reducing Anhedonia in Major Depressive Disorder with Future Event Specificity Training (FEST): A Randomized Controlled Trial. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2023, 47, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bär, A.; Heininga, V.E.; Lemmens, L.; Renner, F. From anticipation to action: A RCT on mental imagery exercises in daily life as a motivational amplifier for individuals with depressive symptoms. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 2024, 16, 1988–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogaert, L.; Hallford, D.J.; Loyen, E.; D’Argembeau, A.; Raes, F. The potential of Future Event Specificity Training (FEST) to decrease anhedonia and dampening of positive emotions: A randomised controlled trial. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 2024, 16, 1245–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.; Li, P.; Lei, X.; Yuan, H. Envision A Bright Future to Heal Your Negative Mood: A Trial in China. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2022, 46, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuijpers, P.; Quero, S.; Noma, H.; Ciharova, M.; Miguel, C.; Karyotaki, E.; Cipriani, A.; Cristea, I.A.; Furukawa, T.A. Psychotherapies for depression: A network meta-analysis covering efficacy, acceptability and long-term outcomes of all main treatment types. World Psychiatry 2021, 20, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Runzi, C.; Wufang, Z.; Yunfeng, W.; Yu, B.; Rongcheng, S.; Zijin, L.; Wenjun, W.; Xiamin, W.; Lin, L. The mental health resources in Chinese mainland by 2020. Chin. J. Psychiatry 2022, 55, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Adolescent Health-SEARO. Available online: https://www.who.int/southeastasia/health-topics/adolescent-health (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Notice on Exploring the Implementation of Specialized Services for Depression Prevention and Treatment. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2020-09/11/content_5542555.htm (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Notice on Launching the “Pediatric and Mental Health Service Year” Initiative (2025–2027). Available online: https://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/c100068/202504/57e9fc983bd74e7cb388af9d2557ecc9.shtml (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Bai, N.; Yin, M. Enhancing sleep and mood in depressed adolescents: A randomized trial on nurse-led digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. Sleep. Med. 2024, 124, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Lee, S.; Song, K.; Kim, M.; Kim, Y.; Kim, H.; Kim, H. A nurse-led mHealth intervention to alleviate depressive symptoms in older adults living alone in the community: A quasi-experimental study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2023, 138, 104431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, K.; Layton, H.; Savoy, C.D.; Ferro, M.A.; Bieling, P.J.; Hicks, A.; Van Lieshout, R.J. Online Public Health Nurse-Delivered Group Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Postpartum Depression: A Randomized Controlled Trial During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2023, 84, 48096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colaizzi, P. Psychological research as a phenomenologist views it. In Existential Phenomenological Alternatives for Psychology; Valle, R.S., King, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978; pp. 48–71. [Google Scholar]

- Maddineshat, M.; Khodaveisi, M.; Kamyari, N.; Razavi, M.; Pourmoradi, F.; Sadeghian, E. Exploring the safe environment provided by nurses in inpatient psychiatric wards: A mixed-methods study. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2024, 31, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darnell, D.; Pierson, A.; Tanana, M.J.; Dorsey, S.; Boudreaux, E.D.; Areán, P.A.; Comtois, K.A. Harnessing Innovative Technologies to Train Nurses in Suicide Safety Planning with Hospital Patients: Formative Acceptability Evaluation of an eLearning Continuing Education Training. JMIR Form. Res. 2024, 8, e56402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahadur, A.G.; Antinucci, R.; Hargreaves, F.; Mak, M.; Moghabghab, R.; Sockalingam, S.; Abdool, P.S. Immersive Virtual Reality Simulation for Suicide Risk Assessment Training: Innovations in Mental Health Nursing Education. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2024, 96, 101608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, H.; Severtson, S.G.; Feldman, B.S.; Drissen, T.; Dwibedi, N.; Cutler, A.J.; Marci, C.D. Clinical burden of major depressive disorder with versus without prominent anhedonia using a real-world electronic health records and claims linked database. BMC Psychiatry 2025, 25, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner-Meichsner, F.; Boelen, P.A.; Hagenaars, M.A. Imagery rescripting in the treatment of prolonged grief disorder: Insights, examples, and future directions. Eur. J. Trauma. Dissociation 2024, 8, 100435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruwys, T.; Steffens, N.K.; Haslam, S.A.; Haslam, C.; Hornsey, M.J.; McGarty, C.; Skorich, D.P. Predictors of social identification in group therapy. Psychother. Res. 2020, 30, 348–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-MacDonald, L.; Lusk, J.; Lee-Baggley, D.; Bright, K.; Laidlaw, A.; Voth, M.; Spencer, S.; Cruikshank, E.; Pike, A.; Jones, C.; et al. Companions in the Abyss: A Feasibility and Acceptability Study of an Online Therapy Group for Healthcare Providers Working During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 801680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilkay, H.İ.; Öztürk Akdeniz, C.; Şirin, B.; Bozkurt Tonguç, A. Investigation of psychiatric nurses’ views on psychotherapy implementation processes: A qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Li, C.; Gao, Q.; Li, L.; Shi, Z. Nurses’ Perspectives on Communication in Acute Psychiatric Care: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2025; Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Question |

|---|---|

| 1 | How much attention do you pay to anhedonia symptoms in patients with MDD during treatment? |

| 2 | In your opinion, how effective is the treatment for anhedonia symptoms in patients with MDD? |

| 3 | Which medications or psychological treatments do you think are effective in improving anhedonia? |

| 4 | What form of episodic future thinking (EFT) training do you think is most suitable? Why? |

| 5 | How long do you think each session should last? |

| 6 | What do you think the frequency of these sessions should be? |

| Participant | Gender | Age (Years) | Professional Title | Position | Education | Years of Work Experience | Years of Experience in Psychological Counseling/ Psychotherapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | Female | 33 | Supervisor Nurse/Intermediate Psychotherapist | None | Bachelor | 9 | 2 |

| N2 | Female | 34 | Supervisor Nurse/Intermediate Psychotherapist | None | Bachelor | 11 | 2 |

| N3 | Female | 32 | Supervisor Nurse/Intermediate Psychotherapist | None | Bachelor | 8 | 2 |

| N4 | Male | 38 | Supervisor Nurse/Intermediate Psychotherapist | Head Nurse | Master | 18 | 3 |

| N5 | Female | 42 | Supervisor Nurse/Intermediate Psychotherapist | Head Nurse | Master | 22 | 2 |

| N6 | Female | 48 | Associate Chief Nurse/Intermediate Psychotherapist | Head Nurse | Master | 29 | 4 |

| N7 | Female | 47 | Attending Physician/Intermediate Psychotherapist | None | Bachelor | 18 | 3 |

| N8 | Male | 34 | Attending Physician/Intermediate Psychotherapist | None | Ph.D. | 10 | 2 |

| N9 | Female | 38 | Associate Chief Physician/Intermediate Psychotherapist | Deputy Chief | Ph.D. | 7 | 5 |

| N10 | Female | 62 | Level-2 Psychological Counselor | None | Associate Degree | 15 | 8 |

| N11 | Female | 43 | Level-2 Psychological Counselor | None | Bachelor | 9 | 9 |

| N12 | Male | 62 | Level-2 Psychological Counselor | None | Bachelor | 27 | 20 |

| N13 | Female | 36 | Level-2 Psychological Counselor | None | Bachelor | 9 | 9 |

| N14 | Male | 32 | Level-2 Psychological Counselor | None | Bachelor | 7 | 7 |

| N15 | Female | 33 | Intermediate Psychotherapist | None | Ph.D. | 4 | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pan, M.; Zou, H.; Luo, D.; Wang, X.Q.; Liu, Q.; Shen, M.; Li, X.; Gong, X.; Yang, B.X. Healthcare Professionals’ Perceptions of Anhedonia in Major Depressive Disorder and the Possibilities of Episodic Future Thinking Training: A Qualitative Study in a Tertiary Care Hospital. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 384. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110384

Pan M, Zou H, Luo D, Wang XQ, Liu Q, Shen M, Li X, Gong X, Yang BX. Healthcare Professionals’ Perceptions of Anhedonia in Major Depressive Disorder and the Possibilities of Episodic Future Thinking Training: A Qualitative Study in a Tertiary Care Hospital. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(11):384. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110384

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Minghao, Huijing Zou, Dan Luo, Xiao Qin Wang, Qian Liu, Meiyu Shen, Xiaofen Li, Xuan Gong, and Bing Xiang Yang. 2025. "Healthcare Professionals’ Perceptions of Anhedonia in Major Depressive Disorder and the Possibilities of Episodic Future Thinking Training: A Qualitative Study in a Tertiary Care Hospital" Nursing Reports 15, no. 11: 384. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110384

APA StylePan, M., Zou, H., Luo, D., Wang, X. Q., Liu, Q., Shen, M., Li, X., Gong, X., & Yang, B. X. (2025). Healthcare Professionals’ Perceptions of Anhedonia in Major Depressive Disorder and the Possibilities of Episodic Future Thinking Training: A Qualitative Study in a Tertiary Care Hospital. Nursing Reports, 15(11), 384. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110384