Nurses’ Perception of the Effect of Motivation, Psycho-Social Safety Climate, and Work Engagement: A Mediation Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation in Nursing Practice

1.2. Work Engagement and Its Relevance to Nursing

1.3. Psychosocial Safety Climate in Healthcare Settings

1.4. Interrelationships and the Research Gap

1.5. Study Aim

1.6. Research Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Psychosocial Safety Climate Scale

2.2. Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES)

2.3. Validity and Reliability

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Motivation and PSC

4.2. Motivation, PSC, and WE

4.3. Mediation Role of PSC

4.4. Implications for Practice

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

4.6. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PSC | psychosocial safety climate |

| WE | work engagement |

References

- Jin, F.; Ni, S.; Wang, L. Occupational stress, coping strategies, and mental health among clinical nurses in hospitals: A mediation analysis. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1537120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziedzic, B.; Łodziana, K.; Marcysiak, M.; Kryczka, T. Occupational stress and social support among nurses. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1621312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelbiso, L.; Belay, A.; Woldie, M. Determinants of motivation among nurses working in Hawassa town public health facilities, South Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2017, 16, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitsios, F.; Kamariotou, M. Job satisfaction behind motivation: An empirical study in public health workers. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dossary, R.N. The relationship between nurses’ quality of work-life on organizational loyalty and job performance in Saudi Arabian hospitals: A cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 857320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghini, F.; Fiorini, J.; Piredda, M.; Fida, R.; Sili, A. The relationship between nurse managers’ leadership style and patients’ perception of the quality of the care provided by nurses: A cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 101, 103446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruzevicius, J.; Valiukaite, J. Quality of life and motivation balance: Case study of public and private sectors of Lithuania. Qual. Access Success 2017, 18, 77–81. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, B.D.S.; Nery, A.A.; Cardoso, J.P. Occupational stress and dissatisfaction with motivation in nursing. Texto. Contexto. Enferm. 2017, 26, e5100015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzellino, G.; Dante, A.; Petrucci, C.; Caponnetto, V.; Aitella, E.; Lancia, L.; Ginaldi, L.; De Martinis, M. Intention to leave and missed nursing care: A scoping review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 2025, 8, 100312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awosiku, O.V.; Gbemisola, I.N.; Oyediran, O.T.; Egbewande, O.M.; Lami, J.H.; Afolabi, D.; Okereke, M.; Effiong, F. Role of digital health technologies in improving health financing and universal health coverage in Sub-Saharan Africa: A comprehensive narrative review. Front. Digit. Health 2025, 7, 1391500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, M.; Saikia, A. Determinants of work engagement among nurses in Northeast India. J. Health Manag. 2019, 21, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, S.E. Associations among leadership, resources, and nurses’ work engagement: Findings from the fifth korean Working Conditions Survey. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Xun, Y. Work engagement and associated factors among dental nurses in China. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platania, S.; Morando, M.; Caruso, A.; Scuderi, V. The effect of psychosocial safety climate on engagement and psychological distress: A multilevel study on the healthcare sector. Safety 2022, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinsser, K.; Zinsser, A. Two case studies of preschool psychosocial safety climates. Res. Hum. Dev. 2016, 13, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollard, M.; Dormann, C.; Idris, M.A. Psychosocial safety climate: A new work stress theory and implications for method. In Psychosocial Safety Climate; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, P.M.; Dóci, E. Neoliberal ideology in work and organizational psychology. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2018, 27, 536–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgoin Boucher, K.; Ivers, H.; Biron, C. Mechanisms explaining the longitudinal effect of psychosocial safety climate on work engagement and emotional exhaustion among education and healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, S.; Tuckey, M.; Dollard, M. Psychosocial safety climate, workplace bullying, and symptoms of posttraumatic stress. Organ. Dev. J. 2010, 28, 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Garrick, A.; Mak, A.; Cathcart, S.; Winwood, P.; Bakker, A.; Lushington, K. Psychosocial safety climate moderating the effects of daily job demands and recovery on fatigue and work engagement. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2014, 19, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanti, T.; Cortini, M.; Giudice, G.F.; Zappalà, S.; Toscano, F. Safeguarding nurses’ mental health: The critical role of psychosocial safety climate in mitigating relational stressors and exhaustion. AIMS Public Health 2024, 11, 905–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakertzis, E.; Myloni, B. Profession as a major drive of work engagement and its effects on job performance among healthcare employees in Greece: A comparative analysis among doctors, nurses and administrative staff. Health Serv. Manag. Res. 2021, 34, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dollard, M.; Kang, S. Psychosocial Safety Climate Measure; Work Stress Research Group University South Australia: Adelaide, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Akanni, A.; Ajila, C.; Omisile, I.; Ndubueze, K. Mediating effect of work self-efficacy on the relationship between psychosocial safety climate and workplace safety behaviors among bank employees after COVID-19 lockdown. Cent. Eur. Manag. J. 2021, 29, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbuto, J.E., Jr.; Scholl, R.W. Motivation sources inventory: Development and validation of new scales to measure an integrative taxonomy of motivation. Psychol. Rep. 1998, 82, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H. Head nurses’ interpersonal relationship and its effect on work engagement and proactive work behavior at Assuit University Hospitals [master’s thesis]. Assiut Sci. Nurs. J. 2018, 6, 116–125. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Qutaish, R.; Alosta, M.R.; Abu-Shosha, G.; Oweidat, I.A.; Nashwan, A.J. The relationship between transformational leadership, work motivation, and engagement among nurses in Jordanian governmental hospitals. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, S.; Ding, X. The influence of self-determined motivation on patient safety competency among nurses: The chain mediating effect of psychological contract and psychological capital. Nurse Educ. Today 2025, 152, 106758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Han, L.; Liang, X.; Wang, R.; Fan, H.; Jia, Y.; Li, S.; Jiang, X. The relationship between transformational leadership and work engagement among intensive care unit nurses: The mediating function of organizational climate. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, G.; Abdelazeem, S.; Abdallah, H. The relationship between motivation and occupational stress among head nurses in Port Said hospitals. Port Said Sci. J. Nurs. 2020, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hossny, E.K. Studying nursing activities in inpatient units: A road to sustainability for hospitals. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossny, E.K.; Alotaibi, H.S.; Mahmoud, A.M.; Elcokany, N.M.; Seweid, M.M.; Aldhafeeri, N.A.; Abdelkader, A.M.; Elhamed, S.M.A. Influence of nurses’ perception of organizational climate and toxic leadership behaviors on intent to stay: A descriptive comparative study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 2023, 5, 100147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkorashy, H.; Alanazi, M. Personal and job-related factors influencing the work engagement of hospital nurses: A cross-sectional study from Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2023, 11, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lateef, S.F.; Mohamed, F.R.; Hossny, E.K. The relationship between motivation, psycho-social safety climate and nursing staff work engagement and organizational commitment. Assiut Sci. Nurs. J. 2021, 9, 18–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hossny, E.K.; Morsy, S.M.; Ahmed, A.M.; Saleh, M.S.M.; Alenezi, A.; Sorour, M.S. Management of the COVID-19 pandemic: Challenges, practices, and organizational support. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, A.M. The effect of COVID-19 on health insurance: The mediating role of demographics and healthcare service utilization. Sci. J. Commer. Res. 2023, 2, 202–218. [Google Scholar]

- Hossny, E.K.; Alotaibi, H.S. Relationship between dominant decision-making style and creativity of nursing managers: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorour, M.S.; Hossny, E.K.; Mohamed, N.T.; Abdelkader, A.M.; Alotaibi, H.S.; Obied, H.K. Effect of head nurses’ workplace polarity management educational intervention on their coaching behavior. Nurs. Res. Pract. 2023, 2023, 5954857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltaybani, S.; Igarashi, A.; Yamamoto-Mitani, N. Palliative and end-of-life care in Egypt: Overview and recommendations for improvement. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2020, 26, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | n | % | M ± SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 36.26 ± 8.97 | 21–56 | ||

| <30 | 96 | 30.2 | ||

| 30–40 | 114 | 35.8 | ||

| >40 | 108 | 34.0 | ||

| Educational qualification | ||||

| Diploma | 189 | 59.4 | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 129 | 40.6 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 69 | 21.7 | ||

| Married | 249 | 78.3 | ||

| Years of experience | 16.27 ± 8.94 | 1–34 | ||

| <10 | 90 | 28.3 | ||

| 10–20 | 117 | 36.8 | ||

| >20 | 111 | 34.9 |

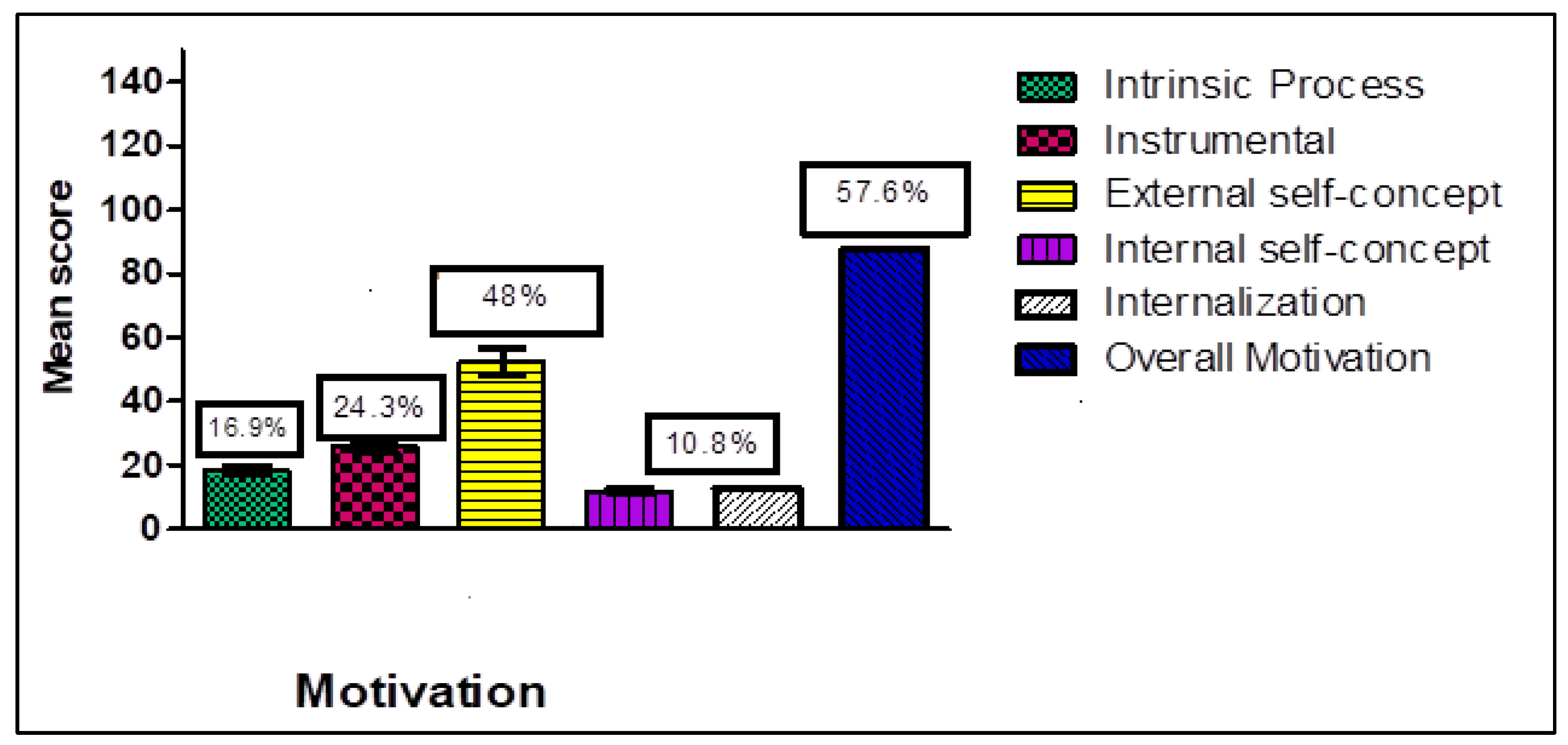

| Variable/Dimension | M ± SD | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Motivation | 118.1 ± 16.4 | 71–186 |

| Intrinsic process | 19.9 ± 3.7 | 8–26 |

| Instrumental | 28.7 ± 4.6 | 20–42 |

| External self-concept | 56.6 ± 10.4 | 31–94 |

| Internal self-concept | 17.2 ± 5.0 | 8–33 |

| Internalization | 18.0 ± 3.9 | 6–25 |

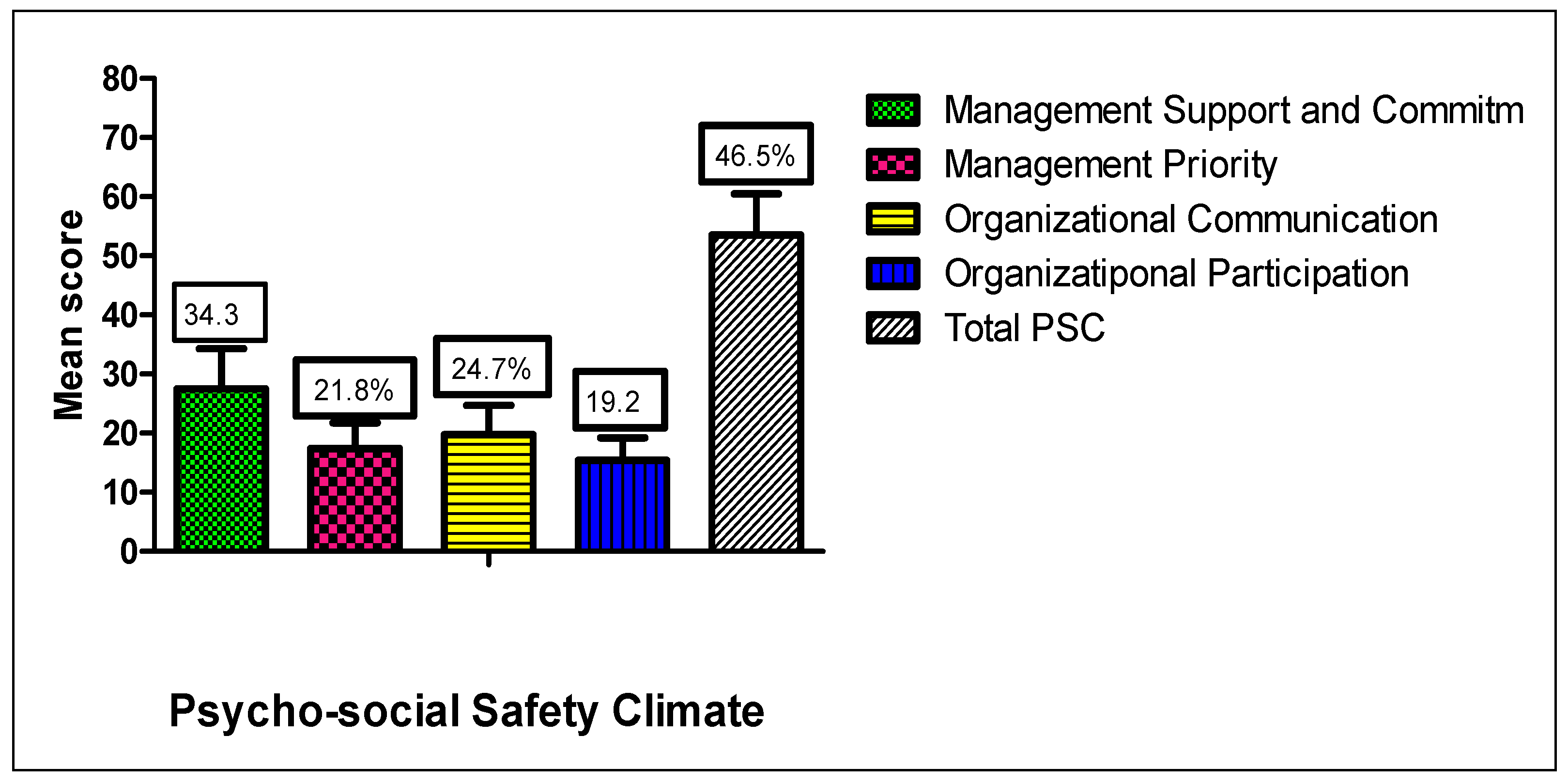

| PSC | 60.5 ± 16.6 | 28–122 |

| Management support & commitment | 20.7 ± 7.0 | 10–46 |

| Management priority | 13.1 ± 4.7 | 5–25 |

| Organizational communication | 14.9 ± 4.3 | 6–30 |

| Participation & involvement | 11.6 ± 4.2 | 5–25 |

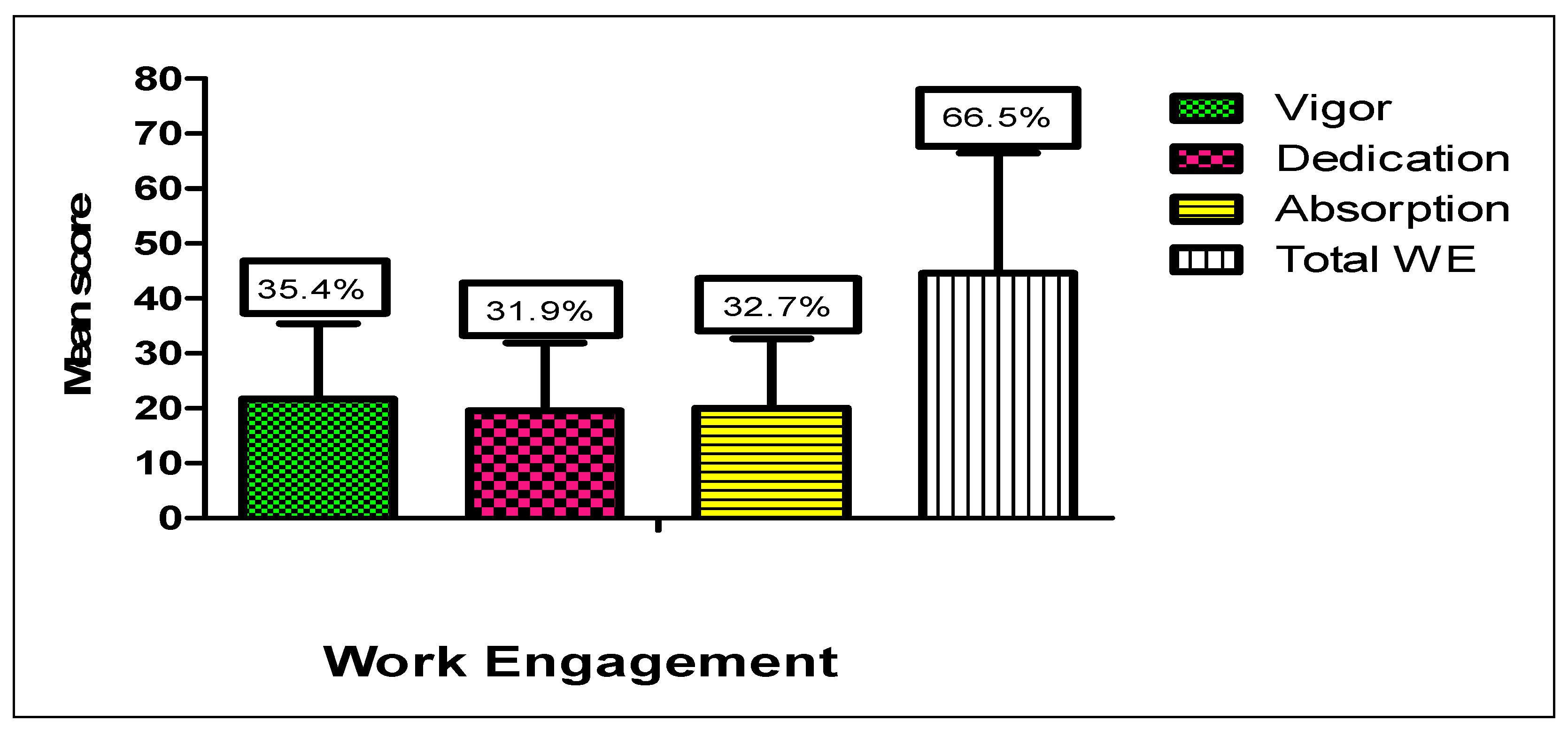

| WE | 22.7 ± 5.8 | 8–33 |

| Vigor | 8.0 ± 2.1 | 3–12 |

| Dedication | 7.2 ± 2.3 | 0–10 |

| Absorption | 7.4 ± 2.6 | 0–12 |

| Variables | r | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motivation—PSC | 0.48 | 0.39, 0.56 | <0.001 * |

| Motivation—WE | 0.10 | −0.01, 0.21 | 0.08 |

| PSC—WE | 0.09 | −0.02, 0.20 | 0.09 |

| Education—PSC | 0.21 | 0.01, 0.36 | 0.035 * |

| Experience—PSC | −0.21 | −0.39, −0.02 | 0.028 * |

| Age—WE | 0.22 | 0.03, 0.39 | 0.021 * |

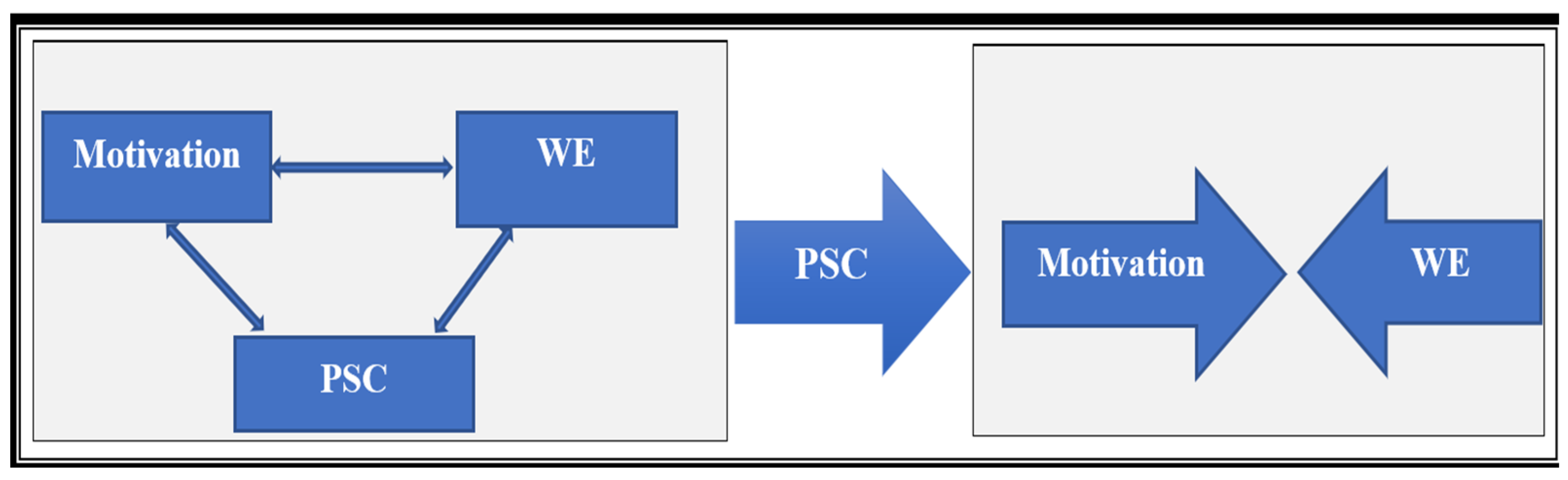

| Pathway | B | SE | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect (Motivation→WE) | 0.05 | 0.03 | −0.01, 0.11 | 0.09 |

| Indirect effect via PSC | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.02, 0.14 | 0.02 * |

| Total effect | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.04, 0.20 | 0.004 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hossny, E.K.; Aboelmagd, N.S.; Aly, S.E.; Elnaeem, M.M.A.; El-aty, N.S.A.; Mahmoud, A.M.; Alsheikh Mohamed, I.; Ahmed, A.M. Nurses’ Perception of the Effect of Motivation, Psycho-Social Safety Climate, and Work Engagement: A Mediation Analysis. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 376. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110376

Hossny EK, Aboelmagd NS, Aly SE, Elnaeem MMA, El-aty NSA, Mahmoud AM, Alsheikh Mohamed I, Ahmed AM. Nurses’ Perception of the Effect of Motivation, Psycho-Social Safety Climate, and Work Engagement: A Mediation Analysis. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(11):376. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110376

Chicago/Turabian StyleHossny, Eman Kamel, Nahed Shawkat Aboelmagd, Shimaa Elwardany Aly, Manal Mohamed Abd Elnaeem, Naglaa Saad Abd El-aty, Aml Moubark Mahmoud, Intisar Alsheikh Mohamed, and Asmaa Mohamed Ahmed. 2025. "Nurses’ Perception of the Effect of Motivation, Psycho-Social Safety Climate, and Work Engagement: A Mediation Analysis" Nursing Reports 15, no. 11: 376. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110376

APA StyleHossny, E. K., Aboelmagd, N. S., Aly, S. E., Elnaeem, M. M. A., El-aty, N. S. A., Mahmoud, A. M., Alsheikh Mohamed, I., & Ahmed, A. M. (2025). Nurses’ Perception of the Effect of Motivation, Psycho-Social Safety Climate, and Work Engagement: A Mediation Analysis. Nursing Reports, 15(11), 376. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110376