Abstract

Introduction: Urinary and fecal incontinence, as well as the presence of an ostomy, are globally prevalent conditions with substantial implications for individuals’ daily lives. Among the psychological consequences, social isolation is a frequently reported experience but remains poorly explored in the existing literature. The aim of this scoping review is to explore how social isolation has been conceptualized and operationalized in research on individuals with incontinence and to synthesize evidence on its antecedents and outcomes. Methods: This review was conducted in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute guidelines and reported following the PRISMA-ScR checklist. Data were thematically synthesized and interpreted according to the Middle Range Theory of Social Isolation in Chronic Illness. Results: Twenty-three studies met the inclusion criteria. Findings indicate that social isolation among individuals with incontinence is a complex, multifactorial phenomenon. Predisposing factors included individual needs for social interaction and desire for approval, psychological resilience, toilet accessibility, education, income, gender, and age. Precipitating factors were related to illness trajectory and adaptation processes, including ostomy acceptance, time since ostomy creation or oncological treatment, sense of belonging, perceived social support, stigma, self-esteem, clinical severity, illness-related conditions, and loss of autonomy. Reported outcomes were consistently adverse, encompassing depression, anxiety, and reduced quality of life. Conclusions: Social isolation represents a core dimension of the lived experience of incontinence and should be recognized as a key clinical outcome. Systematic screening and targeted interventions should be integrated into continence care pathways. Future research should adopt longitudinal and interventional designs to clarify causal mechanisms and evaluate strategies to prevent and mitigate isolation.

1. Introduction

Incontinence refers to the involuntary loss of urine or feces, which can significantly impair daily functioning and quality of life. Urinary incontinence is defined by the International Continence Society as “any involuntary leakage of urine” [1]. Fecal incontinence encompasses the unintentional loss of solid or liquid stool or gas [2]. In some cases, individuals carry a urinary or intestinal stoma, which is a surgically created opening that bypasses normal elimination pathways due to chronic illness, injury, or cancer. The presence of an ostomy leads to a permanent change in continence function. These conditions, often considered benign, or even normal parts of the aging process, are in fact chronic health problems requiring long-term management [3].

Urinary incontinence affects more than 400 million people over the age of 20, representing more than 20% of the global adult population [4]. Fecal incontinence is less prevalent, but still significant, with global estimates ranging from 5% to 10%, depending on age, gender, and comorbidity burden [5]. Regarding ostomy, about 1 million individuals in the United States are estimated to be living with this device, which often results from colorectal cancer of inflammatory bowel disease [6].

Incontinence is associated with a range of healthcare, functional, and psychological consequences, making it a relevant public health issue. Specifically, incontinence increases the risk of falls, urinary tract infections, subsequently leading to loss of independence, institutionalization, and decreased mobility [7,8]. Psychosocial effects are also profound, with shame, embarrassment, loss of self-esteem, and social isolation being frequently reported [9].

Social isolation is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon that refers to a reduction or absence of meaningful social connections. This phenomenon is typically distinguished into objective social isolation, which involves a measurable reduction in social interactions or network size, and subjective social isolation, often referred to as loneliness, which reflects an individual’s internal perception of being emotionally disconnected from others, regardless of actual social contact [10,11]. While objective isolation is characterized by structural aspects (e.g., living alone, limited social contact), subjective isolation captures the unpleasant feelings of exclusion or emotional detachment.

In the context of urinary and fecal incontinence, as well as living with an ostomy, both forms of isolation are significant and can coexist. Individuals may avoid social situations due to embarrassment, fear of leakage or odor, and stigmatizing attitudes, leading to reduced social participation and concealment behaviors. Even when surrounded by others, they may experience profound loneliness, with feelings of being misunderstood or ashamed [12,13,14].

Social isolation carries significant public health implications. It is associated with increased risks of depression, cognitive decline, falls, and reduced quality of life. It also contributes to delayed help-seeking, diminished self-care, and greater risk of institutionalization [15,16]. As the World Health Organization emphasizes social participation as a key determinant of health, understanding and addressing the social isolation linked to incontinence is essential for improving both individual outcomes and population-level well-being [17].

Despite growing recognition of the psychosocial burden associated with urinary and fecal incontinence, as well as life with an ostomy, the literature remains fragmented and conceptually inconsistent. Definitions and measures of social isolation vary widely, often conflating subjective loneliness with objective social withdrawal. Moreover, few studies apply a theoretical framework to explain the link between incontinence and social isolation, limiting the comparability and clinical relevance of findings. Finally, many studies examine isolated aspects, such as psychological distress, stigma, or quality of life, without offering an integrated understanding of how these factors contribute to social isolation.

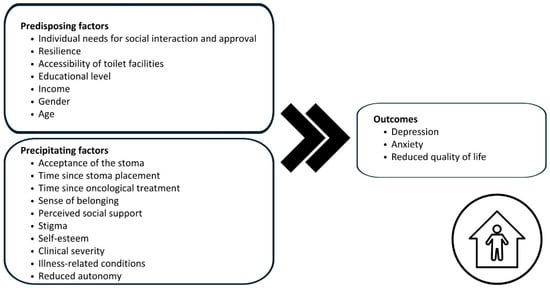

Thus, this scoping review aims to map the phenomenon of social isolation among individuals living with urinary and/or fecal incontinence, including those with an ostomy. This review is guided by the Middle Range Theory of Social Isolation in Chronic Illness [18], which provides a framework for understanding how chronic conditions contribute to or are influenced by social disconnection. The model differentiates between predisposing factors, reflecting stable sociodemographic and psychosocial vulnerabilities, and precipitating factors, referring to illness-related events that may trigger or worsen isolation. The outcomes encompass psychological, social, and health-related dimensions, capturing the wide-ranging effects of isolation on individual well-being. Guided by this theoretical framework, the present review was designed to explore how these constructs have been investigated in the context of incontinence and ostomy.

The research questions were the following: (i) How is social isolation and/or loneliness defined and operationalized in studies involving people with incontinence? (ii) What factors contribute to social isolation in this population? (iii) What are the consequences of social isolation and loneliness (e.g., mental health, quality of life, healthcare use)?

2. Materials and Methods

Scoping reviews are designed to explore and map key concepts and assess studies within a research domain, offering a comprehensive overview of the scope and characteristics of the existing literature [19]. This scoping review was conducted following the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Manual for Evidence Synthesis [20] and the PRISMA-ScR checklist for its construction [21]. The research question was formulated using the Participant-Problem/Concept/Context (PCC) framework [20] which guided the development of the eligibility criteria, keywords, and search strategies (Table 1).

Table 1.

PCC Framework.

2.1. Operationalization of the Concepts

To guide the definition of social isolation and the classification of antecedents and outcomes, we referred to the Middle Range Theory of Social Isolation in Chronic Illness [18], which offers a context-specific lens to understand the construct and interpret the pathways through which chronic health conditions may lead to or be influenced by social isolation. Within this framework, antecedents are distinguished as predisposing factors, representing stable sociodemographic and psychosocial characteristics that shape baseline vulnerability, and precipitating factors, denoting illness-related conditions or events that can initiate or intensify social isolation. The outcomes of social isolation are conceptualized as psychological, social, and health-related consequences that together reflect the broad impact of isolation on individual well-being and clinical trajectories.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria used for study selection were guided by the PCC framework [20] (Table 1). Eligible studies included primary research and review articles employing qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods designs that explored aspects of social isolation, loneliness, social participation, or social interaction in individuals living with an ostomy, urinary incontinence, or fecal incontinence. Studies were included if they involved adult participants (≥18 years), explicitly addressed social or psychosocial dimensions related to the target conditions, were published in English or Italian, and were peer-reviewed full-text articles.

Grey literature such as conference abstracts, dissertations, editorials, and commentaries was excluded due to the absence of peer review and the difficulty in assessing methodological quality. Studies focusing exclusively on clinical or surgical outcomes without reference to social or psychological aspects, as well as non-human studies, were also excluded.

Limits

In the database searches, a language filter was applied to include only studies published in English or Italian, while no time restriction was used to capture all available literature on the topic. In Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and PsychInfo databases the filters “exclude dissertations” and “exclude MEDLINE records” were applied to avoid grey literature and duplicate records already retrieved through the MEDLINE search.

2.3. Search Strategies

A three-step search strategy was implemented in accordance with JBI guidelines [20]. First, a preliminary search of MEDLINE (via PubMed) and CINAHL was performed to identify relevant keywords and indexed terms. Second, a comprehensive search using all identified terms was conducted across MEDLINE, CINAHL, and PsycINFO in July 2024 and updated in May 2025. Finally, the reference lists of the studies included were screened to identify additional records. Search strategies were developed in collaboration with a university research librarian and included both controlled vocabulary (e.g., MeSH terms) and free-text keywords, adapted to the syntax and indexing of each database. The main search concepts combined terms related to social connectedness (“social isolation,” “loneliness,” “social participation,” “social interaction”) and stoma- or incontinence-related conditions (“ostomy,” “surgical stoma,” “urinary incontinence,” “fecal incontinence”). Boolean operators (AND/OR) were used to combine these concepts appropriately, ensuring sensitivity and specificity across databases (Table S1).

2.4. Document Selection

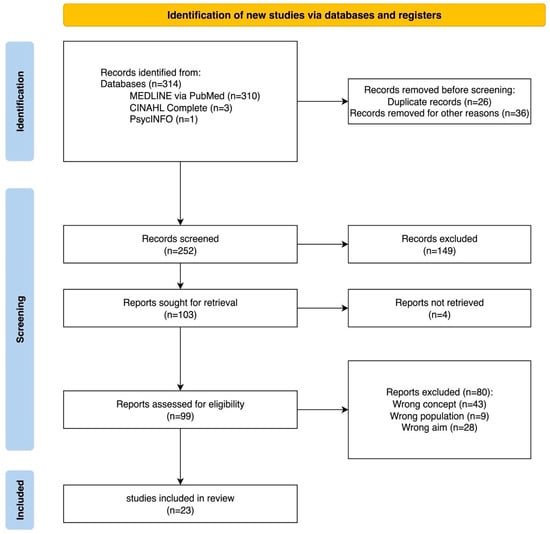

The study selection process followed the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram [22] (Figure 1). Screening was conducted using the web application Rayyan (MA, USA) [23] in two steps. The first step involved selecting records based on title and abstract by two independent reviewers (V.S., I.M.). After this preliminary selection, full texts of the selected records were assessed independently by two reviewers (V.S., I.M.). Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion or with the assistance of a third senior reviewer (G.V.). Records were systematically collected, duplicates removed using Zotero (version 7.0.27; VA, USA) [24], and manually sorted. In line with JBI guidance, no formal quality appraisal was performed [25].

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram 2020: selection process.

2.5. Data Extraction

Metadata from the selected records were extracted using Zotero reference manager software (version 7.0.24) [24] and manually verified upon import. A data extraction table was developed based on the JBI guidelines [20] and subsequently expanded to include additional variables of interest. Specifically, data extraction captured the presence of theoretical models adopted to conceptualize social isolation, as well as the identification of its antecedents and outcomes. All data were manually extracted and organized in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (version 16.98).

2.6. Data Presentation

Data were analyzed thematically to identify recurring concepts and patterns. The classification of antecedents and outcomes of social isolation was organized and presented according to the Middle Range Theory of Social Isolation in Chronic Illness [18].

3. Results

3.1. Selection Process Description

The database searches yielded a total of 314 records. After removing 26 duplicates and 36 records excluded for other reasons (e.g., non-research material or unavailable language), 252 records remained for screening. During title and abstract screening, 149 records were excluded as not pertinent to the research question.

A total of 103 potentially eligible records were sought for full-text retrieval. Four of these could not be accessed despite assistance from the institutional library service and attempts to contact the corresponding authors. Consequently, 99 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 80 were excluded for not meeting the predefined inclusion criteria, specifically, 43 for not addressing the target concept, 9 for non-eligible population, and 28 for aims unrelated to the review question. Ultimately, 23 studies met all criteria and were included in the final synthesis. The selection process is summarized in Figure 1.

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

Table 2 summarizes the studies included in the review, highlighting their design, setting, aims, sample characteristics, and main findings related to social isolation.

Table 2.

Summary of the included studies.

The included articles were published between 1984 and 2024, with a publication peak between 2015 and 2022. Of the 23 records, 12 were quantitative studies [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45], eight (34.78%) were qualitative studies [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,49], and three (13.04%) were reviews (two metasyntheses and one systematic review) [46,47,48]. Sample sizes varied according to study design: qualitative studies included 11–33 participants, whereas quantitative studies enrolled 303–16,369 participants. The reviews synthesized between 20 and 95 articles. Participants ranged in age from 6 to 97 years, with most samples predominantly composed of women (female representation: 51.5–100%). Only one study focused on a pediatric population [32].

Regarding health conditions, 13 studies (56.5%) addressed urinary incontinence, one (4.3%) focused on fecal incontinence, four (17.4%) examined individuals with an ostomy, and five (21.7%) investigated combinations of these conditions. Social isolation was the primary outcome in 14 studies (61%), while in the remaining nine (39%) it emerged as a secondary theme (Table S2).

3.3. Results Synthesis

Driven by the Middle Range Theory of Social Isolation [18], the findings were organized into three subthemes: conceptualization of social isolation, antecedents of social isolation, and outcomes of social isolation.

3.3.1. Conceptualization of Social Isolation

None of the included studies explicitly adopted a theoretical framework to define social isolation. Nevertheless, three recurrent dimensions emerged across the evidence base: (i) subjective isolation, characterized by individual perceptions of emotional or relational disconnection from others [27,29,34,40,41,42,43,45]; (ii) interaction-related isolation, described as discomfort in social interactions, avoidance of participation, and progressive withdrawal from interpersonal relationships [26,28,30,31,35,37,39,44,47,48,49]; and (iii) objective or structural isolation, associated with tangible barriers such as physical, environmental, or logistical constraints [33,36,38,46]. In this dimension, social isolation was frequently operationalized through behavioral indicators such as being homebound (going out once per week or less), withdrawal from structured activities, or reduced participation in regular social interactions [29,36]. One study [32] also suggested that social isolation may extend to parents and caregivers, who can experience emotional strain and withdrawal related to the burden of care.

Quantitative studies most often measured isolation using the UCLA Loneliness Scale [34,41] and the De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale—Short Form [45]. The UCLA scale assesses perceived isolation, lack of companionship, and social exclusion, whereas the De Jong Gierveld scale captures both emotional and social loneliness, which include the absence of close emotional bonds and perceptions of insufficient contact with other community members.

3.3.2. Antecedents of Social Isolation

Predisposing Factors

Social participation emerged in several studies as a key protective factor against isolation. Takahashi et al. [29] described motivation to engage with others as a resource that fosters activation and relational resilience, even in the presence of physical or psychosocial limitations. However, other studies have emphasized that when social exchanges are perceived as superficial or lacking genuine interest, they can paradoxically reinforce feelings of distance and alienation [27,48].

Psychological resilience was also highlighted as relevant in the context of incontinence. Takahashi et al. [29] underscored the importance of the Sense of Coherence (SOC), particularly the “meaningfulness” component, in helping individuals maintain a sense of purpose and resist disengagement. These findings suggest that resilience resources may mitigate, though not completely eliminate, experiences of isolation.

In addition, social attitudes contributed to variations in isolation. Fultz and Herzog [40] reported that individuals with a stronger desire for social approval were less likely to acknowledge the emotional impact of urinary incontinence on their self-perception. This suggests that some individuals may downplay or minimize their difficulties to conform to social expectations and avoid stigmatization.

Environmental accessibility of toilet facilities was a recurring factor in determining isolation. A lack of private, clean, and accessible toilets was repeatedly associated with greater social withdrawal [29,33]. Many individuals reported structuring their daily routines around toilet availability and avoiding public or social settings for fear of not being able to manage incontinence episodes. This dependency, described as a “toilet-bound” condition, restricted social mobility and contributed to disengagement [27]. Conversely, the presence of secure and accessible toilets promoted confidence and participation [38]. Similar dynamics were observed in schools and workplaces, where inadequate facilities limited educational involvement, peer interactions, and professional activities, sometimes resulting in reduced working hours, role changes, or job loss [26,27,33,49]. Consistently, the systematic review by Capilla-Díaz et al. [46], emphasized that individuals with intestinal ostomy face persistent challenges related to odor control and job security.

Socioeconomic characteristics, such as education and income, also emerged as structural determinants of isolation. Lower educational attainment was significantly associated with greater loneliness among individuals with incontinence [40], suggesting that education may act as a protective resource. Similarly, low income was linked to higher isolation levels among people with an ostomy [37].

Gender-related findings were mixed. Some studies reported no differences in perceived loneliness between men and women [41,45], whereas others found that men were more likely to experience activity limitations due to urinary incontinence [40]. Conversely, Li et al., [37] reported a higher incidence of social isolation among women with permanent colostomies [37].

Finally, age was consistently associated with social participation. Older adults were more likely to experience reduced social participation, partly due to functional limitations, comorbidities, and increased reliance on environmental supports [38].

Precipitating Factors

Non-acceptance of one’s condition emerged as a key determinant of social isolation. Among individuals with an ostomy, difficulties in adapting to the device were frequently linked to loneliness, loss of family roles, and reduced intimacy within couples, often resulting in estrangement and social withdrawal [27,46].

Illness trajectory also influenced experiences of isolation. Participants in Pape et al. [27] described loneliness as most pronounced in the period immediately following stoma creation and cancer treatment, with gradual improvement over time as coping strategies and hope developed—though isolation never fully disappeared. Similarly, among incontinent cancer patients, loneliness peaked during the early post-treatment phase, gradually lessening with adaptation but often persisting over time [27,39,46].

A diminished sense of belonging was another recurrent theme. In Malawi, women with obstetric fistula (a childbirth-related injury leading to continuous urinary or fecal incontinence) reported profound exclusion from family and community life, which severely undermined both their social identity and personal sense of belonging [28]. Likewise, patients with colorectal cancer described how social isolation weakened interpersonal ties and eroded feelings of belonging in everyday relationships [37].

In older adults with incontinence, low social support more than doubled the likelihood of experiencing loneliness [41]. Conversely, in individuals with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), informal networks of family, friends, or peers were reported to reduce loneliness and improve adjustment [48]. Interestingly, Takahashi et al. [38] observed that greater perceived support was sometimes associated with being homebound, possibly reflecting that those with greater functional limitations and existing social isolation are also those who receive more assistance, rather than suggesting that support itself leads to isolation.

Stigma consistently emerged as one of the most prominent precipitating factors. Shame and fear of judgment discouraged disclosure, encouraged avoidance, and reinforced isolation [27,28]. Anticipated stigma often led individuals to limit activities to avoid embarrassment. For example, MacDonald & Anderson [39] reported that many patients had never disclosed the presence of an ostomy even to close family members or partners. Similar concealment behaviors were observed among women with obstetric fistula, who deliberately restricted social interactions to minimize the risk of symptom exposure [28]. Children with spina bifida also reported avoiding even trusted social contexts for fear that peers might discover their condition [32]. Among older adults, many deliberately withdrew from social life to conceal incontinence and prevent gossip or public accidents [31]. Comparable patterns were observed among colostomy patients, where fear of odors, noises, or stigmatization led to reduced social and professional engagement, reluctance to disclose their condition, and even avoidance of intimacy [46]. These concealment strategies often lead to voluntary self-exclusion, which is used as a means of protection against rejection or humiliation.

Self-esteem was frequently reported as a negative determinant of isolation. In the Malawian study, women described developing deeply negative self-perceptions—either after others reacted to accidental symptom disclosure or after witnessing the public humiliation of peers with similar conditions. These experiences fostered feelings of inferiority, eroded self-confidence, and prompted further withdrawal, with some participants even describing themselves as “not real persons” or “damaged,” equating bodily dysfunction with a diminished social identity and human worth [28]. Among older adults with incontinence, poor symptom management was linked to reduced self-esteem and greater social withdrawal, whereas effective control was associated with improved participation and reduced isolation [31]. Likewise, in rectal cancer patients, social isolation was directly associated with lower self-esteem [39].

Clinical severity and illness-related conditions were consistently associated with greater social isolation. Individuals with more severe incontinence were more likely to experience significant social restrictions and loneliness compared to those with milder symptoms [40]. Several studies [34,44] suggested that disease severity, together with illness-related stigma, amplified the psychological burden of incontinence and intensified feelings of isolation. Qualitative evidence confirmed that severe signs and symptoms, such as visible leakage, noticeable odors, and urgency, limited social participation and encouraged withdrawal [33,46]. Interestingly, in some cases, the severity of symptoms served as a trigger for help-seeking, prompting individuals to seek medical or professional support [47].

Reduced autonomy also emerged as an important factor. Takahashi et al. [38] reported that individuals with urinary incontinence who were dependent on walking aids were more likely to be homebound, indicating that mobility impairment is a substantial risk factor for social isolation. Similarly, reduced independence in managing incontinence was linked to greater withdrawal, whereas individuals able to self-manage their symptoms experienced better social integration [29,31,49]. Those reliant on caregivers were reported to be excluded more frequently, suggesting that autonomy plays a protective role against isolation.

Outcomes of Social Isolation

The outcomes of social isolation were consistently negative, spanning psychological, social, and quality-of-life domains.

Psychosocial consequences were the most frequently reported, with isolation associated with sadness, depression, and anxiety [27,28,40,45]. Participants often described loss of motivation, emotional estrangement from others, and erosion of intimacy within couples [27,28]. Internalized shame deepened these effects, leading to guilt, a fractured sense of identity, and feelings of being “damaged” or “abnormal” [28,32,39,48]. Concealment and avoidance strategies reinforced this emotional distance, often extending even to close relationships [39].

Quality of life was consistently reported as poor among individuals experiencing social isolation [27,44,46]. Participants frequently described feeling confined to their homes, with the unpredictability of symptoms—especially bowel urgency—restricting daily life and reinforcing a sense of entrapment [27]. Quantitative analyses confirmed that isolation was a major contributor to reduced quality of life [44].

Overall, the evidence indicates that social isolation in people with incontinence is not a peripheral issue but a core component of their lived experience, one that profoundly shapes mental health and overall well-being. Figure 2 summarises our findings.

Figure 2.

Antecedents and outcomes of social isolation in individuals living with incontinence.

4. Discussion

This scoping review systematically mapped the literature on social isolation among individuals living with urinary or fecal incontinence and those with an ostomy, using the Middle Range Theory of Social Isolation in Chronic Illness [18] as an interpretative framework. To our knowledge, this is the first review to provide a structured synthesis of the antecedents and outcomes of social isolation in this population, offering both clinical and theoretical insights.

From a theoretical standpoint, our findings reveal that none of the included studies explicitly applied a conceptual framework to define or analyze social isolation. This lack of theory-driven approaches limits comparability and interpretability across studies. By applying the Middle Range Theory of Social Isolation, this review demonstrates its usefulness in organizing heterogeneous evidence and highlights the need for future research to systematically consider both subjective and objective dimensions of isolation.

The Middle Range Theory of Social Isolation [18] conceptualizes social isolation as a multidimensional phenomenon encompassing both loneliness (as subjective emotional experience) and social disconnectedness (an objective reduction in social contact and participation). Our synthesis indicates that, in the context of incontinence, research has focused predominantly on the subjective dimension—loneliness—while objective indicators, such as reduced participation in activities or homebound status, have been less frequently investigated. This gap highlights the need for future studies to systematically address both dimensions to provide a more comprehensive understanding of isolation in this population.

The findings by Stickely [34] show that loneliness can occur even in the presence of an active social network when there is a mismatch between desired and actual relationships. For individuals with incontinence, this mismatch often reflects compromised parental or spousal roles, disrupted intimacy, and weakened family belonging. When communication, sexuality, or emotional reciprocity are impaired, relationships may lose emotional value, fostering feelings of inadequacy, detachment, and estrangement [27]. The feeling of being misunderstood—especially regarding invisible or trivialized symptoms—can further intensify isolation, even in the context of close relationships [29,48]. Interactions perceived as insensitive or humiliating may be experienced as discouraging, prompting emotional withdrawal and progressive disengagement, which over time consolidate a state of social disconnection [27].

Moreover, it is important to acknowledge that social isolation does not affect only individuals living with incontinence or those with an ostomy but also extends to their close relatives and caregivers. Fischer’s study [32] suggests that social isolation may also affect parents and caregivers of incontinent patients, who can experience emotional strain and social withdrawal related to the burden of care. This finding points to the relational nature of isolation and highlights the need for further research on caregivers’ experiences.

Consistent with previous literature on social isolation in other chronic conditions [50,51], our synthesis indicates that predisposing factors represent structural vulnerabilities that reduce individuals’ capacity to cope with the challenges of incontinence and increase their risk of isolation. Among these, toilet accessibility and socioeconomic resources were the most frequently reported. Toilet accessibility emerged as a particularly significant determinant in this population [32,46]. Qualitative studies described the state of “being toilet-bound” not only as a practical limitation but also as a symbolic marker of fragility and uncertainty, which undermines a person’s sense of control and social mobility [27]. Consequently, many individuals avoid going out, not because it is impossible, but because they feel unable to do so while maintaining dignity. Similarly, lower education and limited income were repeatedly associated with greater isolation [13,40]. Financial constraints can severely restrict access to continence products, medical care, and supportive environments, thereby limiting the ability to manage symptoms discreetly and increasing the likelihood of withdrawal and social disengagement [52].

Among precipitating factors, stigma consistently emerged as the most prominent mechanism. In the broader literature on chronic illness, stigma has been widely examined, particularly in conditions that are not outwardly visible [53]. Evidence from diseases such as psoriasis and cancer shows that stigma—whether internalized, anticipated, or enacted—can strongly mediate quality-of-life outcomes [54,55]. Similar dynamics were observed among individuals with incontinence, where the concealable yet socially stigmatized nature of the condition fosters shame, concealment, and identity fracture [27,28]. Anticipated stigma frequently led to self-exclusion as a strategy to avoid humiliation [39].

Unlike conditions such as psoriasis or cancer, which may trigger fears of contagion or death and lead to overt social rejection, incontinence poses no risk to others—yet still provokes withdrawal and self-devaluation. Cultural context appears to influence these dynamics: for instance, the Malawian study [28] demonstrated how social norms related to marriage, fertility, and gender roles intensified fears of rejection and abandonment, leading to profound isolation. In Western contexts, stigma was more commonly described in relation to practical barriers or psychological responses. These findings support the idea that stigma stems less from the inherent danger of the condition and more from its visibility and the way it conflicts with cultural expectations around bodily control and social decorum [44].

The studies included in this review reinforce findings from the broader literature on chronic conditions [51]: social isolation is not merely an emotional experience but also exacerbates the negative effects of illness on mental health [27,28,40,45]. Furthermore, evidence indicates that isolation significantly compromises quality of life among individuals with incontinence [27,44,46], mirroring patterns observed in other chronic conditions [56]. These findings underscore that well-being depends not only on physical health but also on the ability to maintain meaningful relationships. Interventions aimed at reducing predisposing and precipitating factors for isolation may therefore contribute to improving quality of life.

4.1. Implications for Practice and Research

This review highlights that social isolation among individuals living with incontinence is a complex, multidimensional phenomenon with significant clinical and psychosocial implications. Identifying the factors that contribute to isolation and understanding their consequences provide an opportunity to develop targeted interventions. Screening for social isolation using validated tools could be incorporated into routine continence care pathways, enabling timely identification of at-risk individuals. Specialized nurses, such as stomal therapy nurses, play a key role not only in providing clinical management but also in supporting patients’ reintegration into social life. At the policy level, these practices should be aligned with public health strategies: both the World Health Organization (WHO) [57] and the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) [50] recognize social isolation as a social determinant of health, associated with higher morbidity, premature mortality, and increased healthcare utilization. Incorporating screening and supportive practices into clinical pathways, therefore, contributes to broader goals of reducing health inequalities, improving quality of life, and promoting population well-being.

From a research perspective, this review supports the use of the Middle Range Theory of Social Isolation in Chronic Illness as a conceptual framework to interpret the experiences of individuals with incontinence. This theory can guide future hypothesis-driven investigations by clarifying the mechanisms through which predisposing and precipitating factors lead to isolation and by identifying mediating processes such as self-concept erosion and loss of perceived control. However, important gaps remain. Objective dimensions of isolation, such as participation frequency and network size, are underexplored and should be systematically investigated. Moreover, health-related behaviors (e.g., self-care) and clinical outcomes of isolation remain insufficiently studied. Future research should include longitudinal designs to track the development and persistence of isolation over time, as well as interventional studies to test effective strategies for its prevention and reduction. Promising approaches may include structured peer-support groups, digital tools to foster connection, and psychoeducational interventions to empower patients and caregivers in coping with the relational and emotional consequences of incontinence.

4.2. Limitations

This review has several limitations. First, only studies published in English or Italian were included, which may have led to the exclusion of relevant evidence published in other languages. This restriction was applied because these are the languages spoken by all members of the research team, allowing accurate interpretation of the data without the risk of translation errors. Second, although both qualitative and quantitative studies were considered, their heterogeneity in terms of population characteristics, cultural context, type of incontinence, and study design limited direct comparability of results. Nevertheless, this variability also enriched the analysis by providing a more comprehensive picture of the phenomenon across diverse settings and populations. Third, the heterogeneity of the included populations represents a key limitation of this review. Most studies focused on urinary incontinence, while ostomy-related evidence remains scarce and largely qualitative. Furthermore, none of the studies distinguished between urinary incontinence subtypes (e.g., overactive bladder vs. stress urinary incontinence), preventing more detailed comparisons. This imbalance restricts generalizability and precludes analysis of condition-specific mechanisms. Future research should examine these subgroups separately to capture differential psychosocial pathways and tailor interventions accordingly. Finally, the review protocol was not pre-registered on a public repository. While registration is not mandatory for scoping reviews, it is increasingly recognized as good practice to enhance methodological transparency and reproducibility.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review provides the first systematic synthesis of evidence on social isolation in individuals with urinary or fecal incontinence and those living with an ostomy. The findings demonstrate that isolation is not a marginal or secondary experience, but a core dimension of the lived experience of incontinence, closely linked with stigma, shame, and withdrawal and associated with adverse mental health outcomes and reduced quality of life. By applying the Middle Range Theory of Social Isolation in Chronic Illness, this review highlights the value of theory-informed approaches for integrating fragmented evidence and guiding both research and clinical practice. Social isolation should be systematically assessed and addressed within continence care pathways as part of person-centered, holistic care.

Future research should adopt longitudinal and interventional designs to clarify causal mechanisms, explore objective indicators of isolation, and evaluate strategies to reduce its impact. Interventions, whether educational, clinical, or community-based, should aim not only to improve continence management but also to promote social participation and protect mental health.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nursrep15110375/s1: Table S1: Keywords and Search strategies; Table S2: Relevance of Social Isolation in the Included Records [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.I. and G.V.; methodology, G.V. and I.M.; investigation, V.S.; data curation, V.S.; writing—original draft preparation, I.M., P.I., A.P., V.S. and R.D.; writing—review and editing, D.F.M., D.R., G.V. and P.I.; visualization, V.S.; supervision, G.V. and D.F.M.; project administration, V.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Public Involvement Statement

No public involvement in any aspect of this research.

Guidelines and Standards Statement

The PRISMA-ScR checklist https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850 was used to report the Scoping Review.

Use of Artificial Intelligence

AI or AI-assisted tools were not used in drafting any aspect of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IBD | Inflammatory Bowel Disease |

| CINAHL | Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| PCC | Population-Problem/Concept/Context |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| SIS | Social Impact Scale |

| SOC | Sense Of Coherence |

| SUI | Stress Urinary Incontinence |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Haylen, B.T.; De Ridder, D.; Freeman, R.M.; Swift, S.E.; Berghmans, B.; Lee, J.; Monga, A.; Petri, E.; Rizk, D.E.; Sand, P.K.; et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) Joint Report on the Terminology for Female Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2010, 21, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dexter, E.; Walshaw, J.; Wynn, H.; Dimashki, S.; Leo, A.; Lindsey, I.; Yiasemidou, M. Faecal Incontinence—A Comprehensive Review. Front. Surg. 2024, 11, 1340720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juma, I.M.; Qassim, T.; Saeed, M.F.; Qassim, A.; Al-Rawi, S.; Al-Salmi, S.; Salman, M.T.; Al-Saadi, I.; Almutawea, A.; Aljahmi, E.; et al. Intestinal Stomas—Current Practice and Challenges: An Institutional Review. Euroasian J. Hepato-Gastroenterol. 2023, 13, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.M. Stress Incontinence in Women. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 2428–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mack, I.; Hahn, H.; Gödel, C.; Enck, P.; Bharucha, A.E. Global Prevalence of Fecal Incontinence in Community-Dwelling Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 22, 712–731.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayik, C.; Özden, D.; Cenan, D. Ostomy Complications, Risk Factors, and Applied Nursing Care: A Retrospective, Descriptive Study. Wound Manag. Prev. 2020, 66, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, I.; Stocking, A.; Fitzner, K.; Ahmed, T.; Huynh, N. The Prevalence of Incontinence and Its Association with Urinary Tract Infections, Dermatitis, Slips and Falls, and Behavioral Disturbances Among Older Adults in Medicare Fee-for-Service. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 2024, 51, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.; Chung, H.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, S.J.; Kwon, O.; Lee, Y.G.; Yu, J.M.; Cho, S.T. The Impact of Urinary Incontinence on Falls: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assmann, S.L.; Keszthelyi, D.; Breukink, S.O.; Kimman, M.L. Living with Faecal Incontinence: A Qualitative Investigation of Patient Experiences and Preferred Outcomes Through Semi-Structured Interviews. Qual. Life Res. 2024, 33, 3121–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Cacioppo, S. Social Relationships and Health: The Toxic Effects of Perceived Social Isolation. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 2014, 8, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.H.-J.; Olmstead, R.; Choi, H.; Carrillo, C.; Seeman, T.E.; Irwin, M.R. Associations of Objective Versus Subjective Social Isolation with Sleep Disturbance, Depression, and Fatigue in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Aging Ment. Health 2019, 23, 1130–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodsky, C.N.; Sitto, H.M.; Wittmann, D.; Wallner, L.P.; Streur, C.; DeJonckheere, M.; Stoffel, J.S.; Cameron, A.P.; Sarma, A.; Clemens, J.Q.; et al. “There Is a Lot of Shame That Comes with This”: A Qualitative Study of Patient Experiences of Isolation, Embarrassment, and Stigma Associated with Overactive Bladder. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2024, 43, 1817–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Rhee, Y.; Choi, K.S. Urinary Incontinence and the Association with Depression, Stress, and Self-Esteem in Older Korean Women. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahan, A.; Çıtak, E.A.; Çevik, B.; Abbasoğlu, A.; Uğurlu, Z. Determining the Perception of Stigma of Individuals with Ostomies. BMC Psychol. 2025, 13, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnera, J.; Yuen, E.; Macpherson, H. The Impact of Loneliness and Social Isolation on Cognitive Aging: A Narrative Review. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Rep. 2023, 7, 699–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, C.; Siu, K.; Xu, I.; Osman, I.; Zhong, J. Social Isolation Changes and Long-Term Outcomes Among Older Adults. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2424519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. From Loneliness to Social Connection—Charting a Path to Healthier Societies; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Iovino, P.; Vellone, E.; Cedrone, N.; Riegel, B. A Middle-Range Theory of Social Isolation in Chronic Illness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Scoping Reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Lockwood, C., Porritt, K., Pilla, B., Jordan, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2024; ISBN 978-0-6488488-2-0. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijai, C.; Natarajan, K.; Elayaraja, M. Citation Tools and Reference Management Software for Academic Writing. SSRN Electron. J. 2019, 14, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors When Choosing Between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esparza, A.O.; Tomás, M.Á.C.; Pina-Roche, F. Experiences of Women and Men Living with Urinary Incontinence: A Phenomenological Study. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2018, 40, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pape, E.; Decoene, E.; Debrauwere, M.; Van Nieuwenhove, Y.; Pattyn, P.; Feryn, T.; Pattyn, P.R.L.; Verhaeghe, S.; Van Hecke, A. The Trajectory of Hope and Loneliness in Rectal Cancer Survivors with Major Low Anterior Resection Syndrome: A Qualitative Study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2022, 56, 102088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changole, J.; Thorsen, V.C.; Kafulafula, U. “I Am a Person but I Am not a Person”: Experiences of Women Living with Obstetric Fistula in the Central Region of Malawi. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Sase, E.; Kato, A.; Igari, T.; Kikuchi, K.; Jimba, M. Psychological Resilience and Active Social Participation Among Older Adults with Incontinence: A Qualitative Study. Aging Ment. Health 2016, 20, 1167–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komorowski, L.; Chen, B. Female Urinary Incontinence in China: Experiences and Perspectives. Health Care Women Int. 2006, 27, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitteness, L.S. The Management of Urinary Incontinence by Community-Living Elderly. Gerontologist 1987, 27, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, N.; Church, P.; Lyons, J.; McPherson, A.C. A Qualitative Exploration of the Experiences of Children with Spina Bifida and Their Parents Around Incontinence and Social Participation. Child Care Health Dev. 2015, 41, 954–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnsen, V.; Skattebu, E.; Aamot-Andersen, A.; Thyberg, M. Problematic Aspects of Faecal Incontinence According to the Experience of Adults with Spina Bifida. J. Rehabil. Med. 2009, 41, 506–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickley, A.; Santini, Z.I.; Koyanagi, A. Urinary Incontinence, Mental Health and Loneliness among Community-Dwelling Older Adults in Ireland. BMC Urol. 2017, 17, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, J.; Wan, X.; Wang, X.; Kane, R.L.; Wang, K. Effects of Stigma on C Hinese Women’s Attitudes Towards Seeking Treatment for Urinary Incontinence. J. Clin. Nurs. 2015, 24, 1112–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.-R.; Park, S.; Kim, J. Urinary Incontinence and Depressive Symptoms: The Mediating Role of Physical Activity and Social Engagement. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2022, 77, 1250–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; He, X.; Qin, R.; Yao, Q.; Dong, X.; Li, P. Linking Stigma to Social Isolation Among Colorectal Cancer Survivors with Permanent Stomas: The Chain Mediating Roles of Stoma Acceptance and Valuable Actions. J. Cancer Surviv. 2024, 19, 2037–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, K.; Kato, A.; Igari, T.; Sase, E.; Shibanuma, A.; Kikuchi, K.; Nanishi, K.; Jimba, M.; Yasuoka, J. Sense of Coherence as a Key to Improve Homebound Status Among Older Adults with Urinary Incontinence. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2015, 15, 910–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, L.D.; Anderson, H.R. Stigma in Patients with Rectal Cancer: A Community Study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 1984, 38, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fultz, N.H.; Herzog, A.R. Self-Reported Social and Emotional Impact of Urinary Incontinence. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2001, 49, 892–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramage-Morin, P.L.; Gilmour, H. Urinary Incontinence and Loneliness in Canadian Seniors. Health Rep. 2013, 24, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Yip, S.O.; Dick, M.A.; McPencow, A.M.; Martin, D.K.; Ciarleglio, M.M.; Erekson, E.A. The Association Between Urinary and Fecal Incontinence and Social Isolation in Older Women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 208, 146.e1–146.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichols, T.R. Social Connectivity in Those 24 Months or Less Postsurgery. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 2011, 38, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Wang, C.; Xu, D.; Guan, X.; Sun, T.; Wang, K. Disease Stigma and Its Mediating Effect on the Relationship Between Symptom Severity and Quality of Life Among Community-Dwelling Women with Stress Urinary Incontinence: A Study from a C Hinese City. J. Clin. Nurs. 2014, 23, 2170–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wong, C.; Sit, R.W.S.; Sun, W.; Zhong, B.; Niu, L.; Zou, D.; Xu, Z.; Wong, S.Y.S. Incontinence and Loneliness Among Chinese Older Adults with Multimorbidity in Primary Care: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2019, 127, 109863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capilla-Díaz, C.; Bonill-de Las Nieves, C.; Hernández-Zambrano, S.M.; Montoya-Juárez, R.; Morales-Asencio, J.M.; Pérez-Marfil, M.N.; Hueso-Montoro, C. Living with an Intestinal Stoma: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Qual. Health Res. 2019, 29, 1255–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, F.; Xiao, L.D.; Zhou, K.; Li, Z.; Tang, S. Perceptions and Help-Seeking Behaviours Among Community-Dwelling Older People with Urinary Incontinence: A Systematic Integrative Review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 1574–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, K. Understanding the Health and Social Care Needs of People Living with IBD: A Meta-Synthesis of the Evidence. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 18, 6240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, S.R.; Villasante-Tezanos, A.; Allen, L.M.; Pappadis, M.R.; Kilic, G. Comparative Effectiveness of Pelvic Floor Muscle Training, Mirabegron, and Trospium among Older Women with Urgency Urinary Incontinence and High Fall Risk: A Feasibility Randomized Clinical Study. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2024, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Behavioral, Cognitive, and Sensory Sciences; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Committee on the Health and Medical Dimensions of Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-0-309-67100-2. [Google Scholar]

- Courtin, E.; Knapp, M. Social Isolation, Loneliness and Health in Old Age: A Scoping Review. Health Soc. Care Community 2017, 25, 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trapani, S.; Villa, G.; Marcomini, I.; Bagnato, E.; Rinaldi, S.; Caglioni, M.; Poliani, A.; Rosa, D.; Salvatore, S.; Candiani, M.; et al. Prevalence, Risk Factors and Costs of Female Urinary Incontinence: A Multicentre Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Urol. Nurs. 2025, 19, e70027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, A.T.; Habenicht, A.E. Stigma Is Associated with Illness Self-Concept in Individuals with Concealable Chronic Illnesses. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2022, 27, 136–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpsoy, E.; Polat, M.; FettahlıoGlu-Karaman, B.; Karadag, A.S.; Kartal-Durmazlar, P.; YalCın, B.; Emre, S.; Didar-Balcı, D.; Bilgic-Temel, A.; Arca, E.; et al. Internalized Stigma in Psoriasis: A Multicenter Study. J. Dermatol. 2017, 44, 885–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Li, Q.; Zhao, H.; Li, J.; Duan, J.; Wang, D.; Fang, N.; Zhu, P.; Fu, J. Quality of Life in Rectal Cancer Patients with Permanent Colostomy in Xi’an. Afr. Health Sci. 2014, 14, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beridze, G.; Ayala, A.; Ribeiro, O.; Fernández-Mayoralas, G.; Rodríguez-Blázquez, C.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, V.; Rojo-Pérez, F.; Forjaz, M.J.; Calderón-Larrañaga, A. Are Loneliness and Social Isolation Associated with Quality of Life in Older Adults? Insights from Northern and Southern Europe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Social Isolation and Loneliness. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/social-determinants-of-health/demographic-change-and-healthy-ageing/social-isolation-and-loneliness (accessed on 11 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).