Legacy in End-of-Life Care: A Concept Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Sources and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Use of Term in Dictionary Definitions

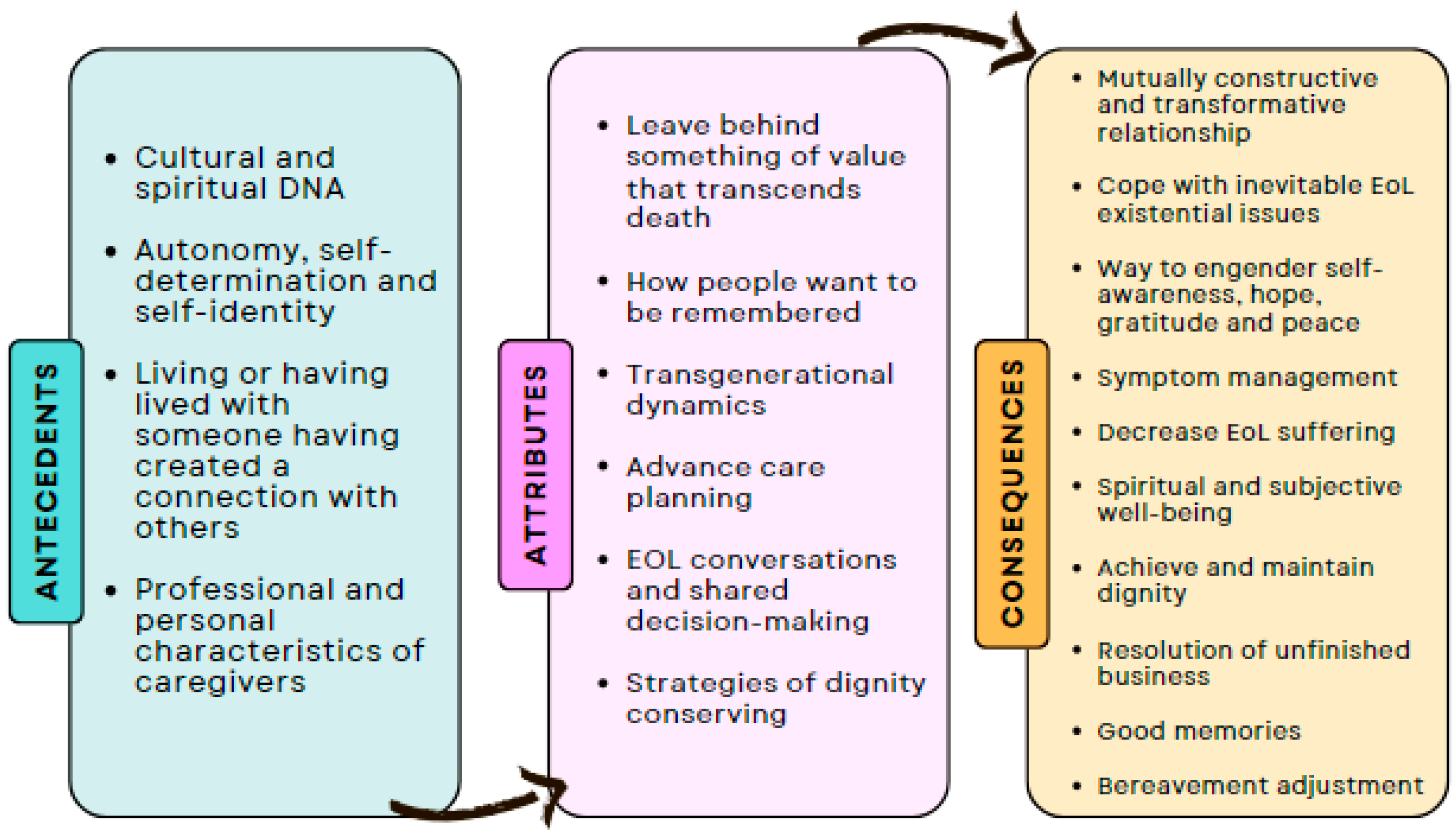

3.2. Defining Attributes

3.3. Constructed Cases

3.3.1. Case Model

3.3.2. Borderline Case

3.3.3. Contrary Case

3.4. Antecedents

3.5. Consequences

3.6. Empirical Referents

3.7. Definition of Concept

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sinclair, S. The Spirituality of Palliative and Hospice Care Professionals: An Ethnographic Inquiry; University of Calgary: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Östlund, U.; Brown, H.; Johnston, B. Dignity conserving care at end-of-life: A narrative review. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2012, 16, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grassi, L.; Nanni, M.G.; Riba, M.; Folesani, F. Dignity in Medicine: Definition, Assessment and Therapy. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2024, 26, 273–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.R.; Cha, Y.J. Dignity therapy for effective palliative care: A literature review. Kosin Med. J. 2022, 37, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitbart, W. Legacy in palliative care: Legacy that is lived. Palliat. Support. Care 2016, 14, 453–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chochinov, H.M.; Kristjanson, L.J.; Breitbart, W.; McClement, S.; Hack, T.F.; Hassard, T.; Harlos, M. Effect of dignity therapy on distress and end-of-life experience in terminally ill patients: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chochinov, H.M.; Hack, T.; McClement, S.; Kristjanson, L.; Harlos, M. Dignity in the terminally ill: A developing empirical model. Soc. Sci. Med. 2002, 54, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallnow, L.; Smith, R.; Ahmedzai, S.H.; Bhadelia, A.; Chamberlain, C.; Cong, Y.; Doble, B.; Dullie, L.; Durie, R.; Finkelstein, E.A.; et al. Report of the Lancet Commission on the Value of Death: Bringing death back into life. Lancet 2022, 399, 837–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, B.; Larkin, P.; Connolly, M.; Barry, C.; Narayanasamy, M.; Östlund, U.; McIlfatrick, S. Dignity-conserving care in palliative care settings: An integrative review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2015, 24, 1743–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H. Existential Issues and Psychosocial Interventions in Palliative Care. Korean J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2020, 23, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Chow, K.M.; Tang, S.; Chan, C.W.H. Development and feasibility of culturally sensitive family-oriented dignity therapy for Chinese patients with lung cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Asia Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2022, 9, 100078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCance, T.; McCormack, B. Developing healthful cultures through the development of person-centred practice. Int. J. Orthop. Trauma Nurs. 2023, 51, 101055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Österlind, J.; Henoch, I. The 6S-model for person-centred palliative care: A theoretical framework. Nurs. Philos. 2021, 22, e12334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laranjeira, C.; Dourado, M. “Dignity as a Small Candle Flame That Doesn’t Go Out!”: An Interpretative Phenomenological Study with Patients Living with Advanced Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 17029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuksanovic, D.; Green, H.; Morrissey, S.; Smith, S. Dignity Therapy and Life Review for Palliative Care Patients: A Qualitative Study. J. Pain Symptom. Manag. 2017, 54, 530–537.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Akard, T.F.; Dietrich, M.S.; Friedman, D.L.; Hinds, P.S.; Given, B.; Wray, S.; Gilmer, M.J. Digital storytelling: An innovative legacy-making intervention for children with cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2015, 62, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akard, T.F.; Dietrich, M.S.; Friedman, D.L.; Wray, S.; Gerhardt, C.A.; Hendricks-Ferguson, V.; Hinds, P.S.; Rhoten, B.; Gilmer, M.J. Randomized Clinical Trial of a Legacy Intervention for Quality of Life in Children with Advanced Cancer. J. Palliat. Med. 2021, 24, 680–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, B.P.; Akard, T.F.; Boles, J.C. Legacy in paediatrics: A concept analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2024, 80, 948–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahalan, L.; Smith, A.; Sandoval, M.; Parks, G.; Gresham, Z. Collaborative Legacy Building to Alleviate Emotional Pain and Suffering in Pediatric Cancer Patients: A Case Review. Children 2022, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa Gray, M.; Ludman, E.J.; Beatty, T.; Rosenberg, A.R.; Wernli, K.J. Balancing Hope and Risk Among Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Patients with Late-Stage Cancer: A Qualitative Interview Study. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2018, 7, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGroot, J.M.; Klass, D.; Steffen, E.M. (Eds.) Continuing Bonds in Bereavement: New Directions for Research and Practice. OMEGA 2019, 79, 340–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, M.R.; Wagoner, S.T.; Young, M.E.; Madan-Swain, A.; Barnett, M.; Gray, W.N. Healing the Hearts of Bereaved Parents: Impact of Legacy Artwork on Grief in Pediatric Oncology. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2020, 60, 790–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumbold, B.; Lowe, J.; Aoun, S.M. The Evolving Landscape: Funerals, Cemeteries, Memorialization, and Bereavement Support. OMEGA-J. Death Dying 2021, 84, 596–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, J.; Rumbold, B.; Aoun, S.M. Memorialisation during COVID-19: Implications for the bereaved, service providers and policy makers. Palliat. Care Soc. Pract. 2020, 14, 263235242098045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueroa Gray, M.; Banegas, M.P.; Henrikson, N.B. Conceptions of Legacy Among People Making Treatment Choices for Serious Illness: Protocol for a Scoping Review. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2022, 11, e40791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boles, J.C.; Jones, M.T. Legacy perceptions and interventions for adults and children receiving palliative care: A systematic review. Palliat. Med. 2021, 35, 529–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.; Avant, K. Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing, 6th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.; Firth, J. Qualitative data analysis: The framework approach. Nurse Res. 2011, 18, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Definition of Housebound. 2024. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/legacy (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Cambridge English Dictionary. Definition of Legacy. 2024. Available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/legacy (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Keall, R.M.; Butow, P.N.; Steinhauser, K.E.; Clayton, J.M. Discussing life story, forgiveness, heritage, and legacy with patients with life-limiting illnesses. Int. J. Palliat Nurs. 2011, 17, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chochinov, H.M. Dignity-Conserving Care—A New Model for Palliative Care: Helping the patient feel valued. JAMA 2002, 287, 2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ent, M.R.; Gergis, M.A. The most common end-of-life reflections: A survey of hospice and palliative nurses. Death Stud. 2020, 44, 256–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harstäde, C.W.; Blomberg, K.; Benzein, E.; Östlund, U. Dignity-conserving care actions in palliative care: An integrative review of Swedish research. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2018, 32, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Post, H.; Wagman, P. What is important to patients in palliative care? A scoping review of the patient’s perspective. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2019, 26, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, A.H.Y.; Leung, P.P.Y.; Tse, D.M.W.; Pang, S.M.C.; Chochinov, H.M.; Neimeyer, R.A.; Chan, C.L.W. Dignity Amidst Liminality: Healing Within Suffering Among Chinese Terminal Cancer Patients. Death Stud. 2013, 37, 953–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, A.H.Y.; Chan, C.L.W.; Leung, P.P.Y.; Chochinov, H.M.; Neimeyer, R.A.; Pang, S.M.C.; Tse, D.M.W. Living and dying with dignity in Chinese society: Perspectives of older palliative care patients in Hong Kong. Age Ageing 2013, 42, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, R.S. The Legacy Project Intervention to Enhance Meaningful Family Interactions: Case Examples. Clin. Gerontol. 2009, 32, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S. Hope in terminal illness: An evolutionary concept analysis. Int. J. Palliat Nurs. 2007, 13, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, A. Practice development using video-reflexive ethnography: Promoting safe space(s) towards the end of life in hospital. Int. Pract. Dev. J. 2016, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsch, K.; Gottschling, S. Wishes and Needs at the End of Life: Communication Strategies, Counseling, and Administrative Aspects. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2021, 118, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, Y.; Wright-St Clair, V.; Goodyear-Smith, F. Exploring the lived experience of migrants dying away from their country of origin. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 2647–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, C. Music therapy preloss care though legacy creation. Prog. Palliat. Care 2013, 21, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewe, F. The Soul’s Legacy: A Program Designed to Help Prepare Senior Adults Cope with End-of-Life Existential Distress. J. Health Care Chaplain. 2017, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, P. Patient Dignity Question: Feasible, dignity-conserving intervention in a rural hospice. Can. Fam. Physician 2019, 65, 812–819. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saracino, R.M.; Rosenfeld, B.; Breitbart, W.; Chochinov, H.M. Psychotherapy at the End of Life. Am. J. Bioeth. 2019, 19, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, D.G. Becky’s Legacy: More Lessons. Death Stud. 2005, 29, 745–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, A.H.Y.; Car, J.; Ho, M.H.R.; Tan-Ho, G.; Choo, P.Y.; Patinadan, P.V.; Chong, P.H.; Ong, W.Y.; Fan, G.; Tan, Y.P.; et al. A novel Family Dignity Intervention (FDI) for enhancing and informing holistic palliative care in Asia: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2017, 18, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mok, E.; Lau, K.P.; Lai, T.; Ching, S. The meaning of life intervention for patients with advanced-stage cancer: Development and pilot study. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 2012, 39, E480–E488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggleby, W.; Wright, K. Elderly palliative care cancer patients’ descriptions of hope-fostering strategies. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2004, 10, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, M.; Morita, T.; Miyashita, M.; Sanjo, M.; Kira, H.; Shima, Y. Factors that influence the efficacy of bereavement life review therapy for spiritual well-being: A qualitative analysis. Support. Care Cancer 2011, 19, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, B.P.M.; Leung, D.; Leung, S.M.; Loke, A.Y. Beyond death and dying: How Chinese spouses navigate the final days with their loved ones suffering from terminal cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.; Lyford, M.; Papertalk, L.; Holloway, M. Passing on wisdom: Exploring the end-of-life wishes of Aboriginal people from the Midwest of Western Australia. Rural. Remote Health 2019, 19, 5444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovland, C.A.; Kramer, B.J. Barriers and Facilitators to Preparedness for Death: Experiences of Family Caregivers of Elders with Dementia. J. Soc. Work End Life Palliat. Care 2019, 15, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C. “I need my granddaughter to know who I am!” A case study of a 67-year-old African American man and his spiritual legacy. J. Health Care Chaplain. 2023, 29, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernat, J.K.; Helft, P.R.; Wilhelm, L.R.; Hook, N.E.; Brown, L.F.; Althouse, S.K.; Johns, S.A. Piloting an abbreviated dignity therapy intervention using a legacy-building web portal for adults with terminal cancer: A feasibility and acceptability study. Psychooncology 2015, 24, 1823–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesse, M.; Forstmeier, S.; Ates, G.; Radbruch, L. Patients’ priorities in a reminiscence and legacy intervention in palliative care. Palliat. Care Soc. Pract. 2019, 13, 2632352419892629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, A. “It’s very humbling”: The Effect Experienced by Those Who Facilitate a Legacy Project Session Within Palliative Care. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2019, 36, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanley, S.; Higginbotham, K.; Finucane, A.; Nwosu, A.C. A grounded theory study exploring palliative care healthcare professionals’ experiences of managing digital legacy as part of advance care planning for people receiving palliative care. Palliat. Med. 2023, 37, 1424–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dönmez, Ç.F.; Johnston, B. Living in the moment for people approaching the end of life: A concept analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 108, 103584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, C.; Gonçalves, A.; Guedes, A.; Pavoeiro, M.; Pinheiro, N.; Santos Silva, R.; Neto, I.G. Creating a legacy—A tool to support end-of-life patients. Eur. J. Palliat. Care 2018, 25, 116–119. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, R.A.M.; Sousa Valente Ribeiro, P.C.P. The context of care as a supporting axis for comfort in a palliative care unit. Palliat. Care Soc. Pract. 2024, 18, 26323524241258781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, A.; Carvalho, M.S.; Laranjeira, C.; Querido, A.; Charepe, Z. Hope in palliative care nursing: Concept analysis. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2021, 27, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicely Saunders Quotes. Available online: https://www.azquotes.com/author/20332-Cicely_Saunders (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Chochinov, H.M. Intensive Caring: Reminding Patients They Matter. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 2884–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjeira, C.; Dixe, M.A.; Semeão, I.; Rijo, S.; Faria, C.; Querido, A. “Keeping the Light On”: A Qualitative Study on Hope Perceptions at the End of Life in Portuguese Family Dyads. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueroa Gray, M.; Randall, S.; Banegas, M.; Ryan, G.W.; Henrikson, N.B. Personal legacy and treatment choices for serious illness: A scoping review. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeSanto-Madeya, S.; Tjia, J.; Fitch, C.; Wachholtz, A. Feasibility and Acceptability of Digital Legacy-Making: An Innovative Story-Telling Intervention for Adults With Cancer. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2021, 38, 772–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizzo, P.A. Thoughts about Dying in America: Enhancing the impact of one’s life journey and legacy by also planning for the end of life. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 12908–12912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Timóteo, C.; Vitorino, J.; Ali, A.M.; Laranjeira, C. Legacy in End-of-Life Care: A Concept Analysis. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 2385-2397. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14030177

Timóteo C, Vitorino J, Ali AM, Laranjeira C. Legacy in End-of-Life Care: A Concept Analysis. Nursing Reports. 2024; 14(3):2385-2397. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14030177

Chicago/Turabian StyleTimóteo, Carolina, Joel Vitorino, Amira Mohammed Ali, and Carlos Laranjeira. 2024. "Legacy in End-of-Life Care: A Concept Analysis" Nursing Reports 14, no. 3: 2385-2397. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14030177

APA StyleTimóteo, C., Vitorino, J., Ali, A. M., & Laranjeira, C. (2024). Legacy in End-of-Life Care: A Concept Analysis. Nursing Reports, 14(3), 2385-2397. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14030177