Validation of Two Questionnaires Assessing Nurses’ Perspectives on Addressing Psychological, Social, and Spiritual Challenges in Palliative Care Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

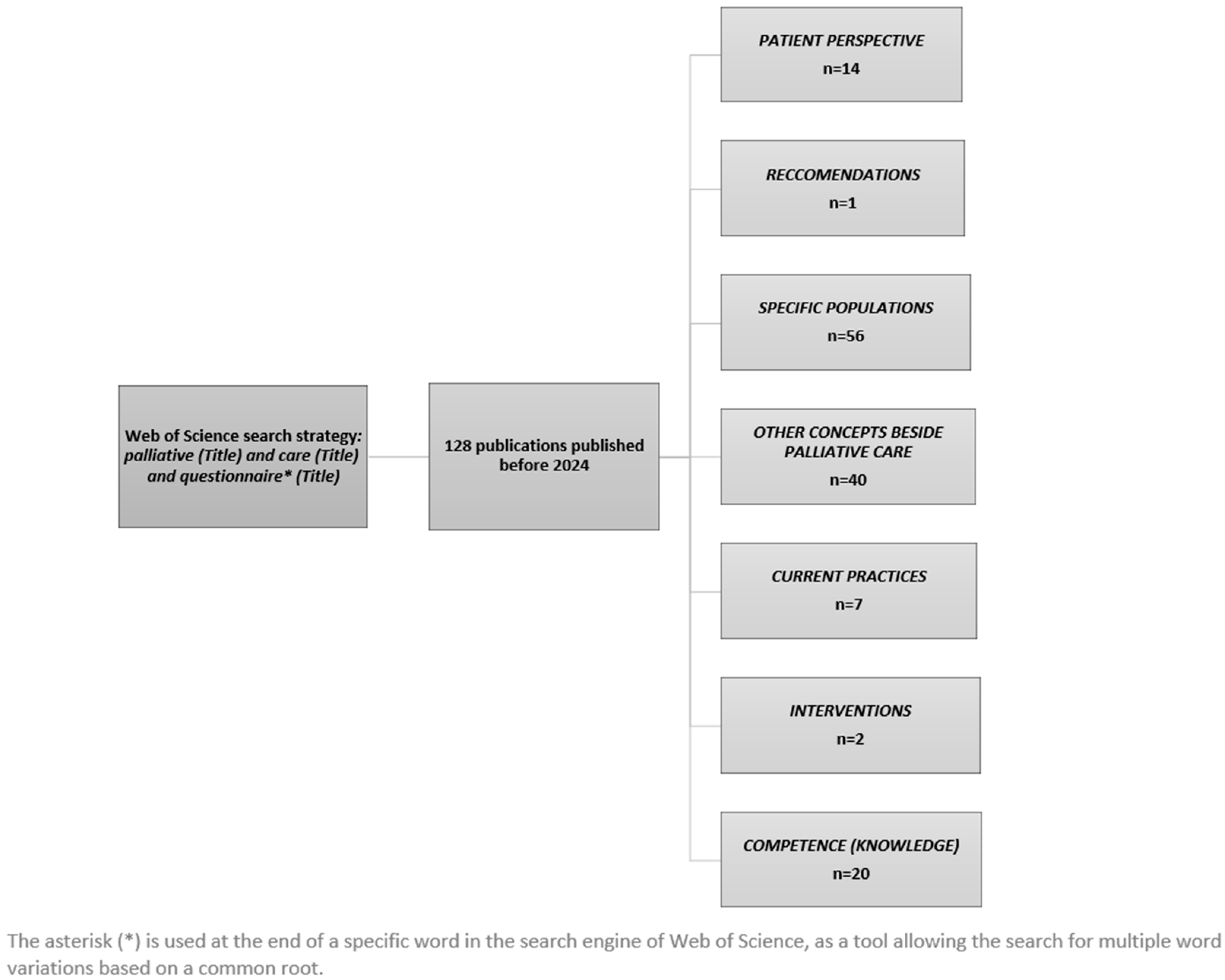

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Questionnaire Development and Validation

2.2.1. Item Development

2.2.2. Content Validity

2.2.3. Factor Analysis

2.3. Participants Selection and Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Sample Characteristics

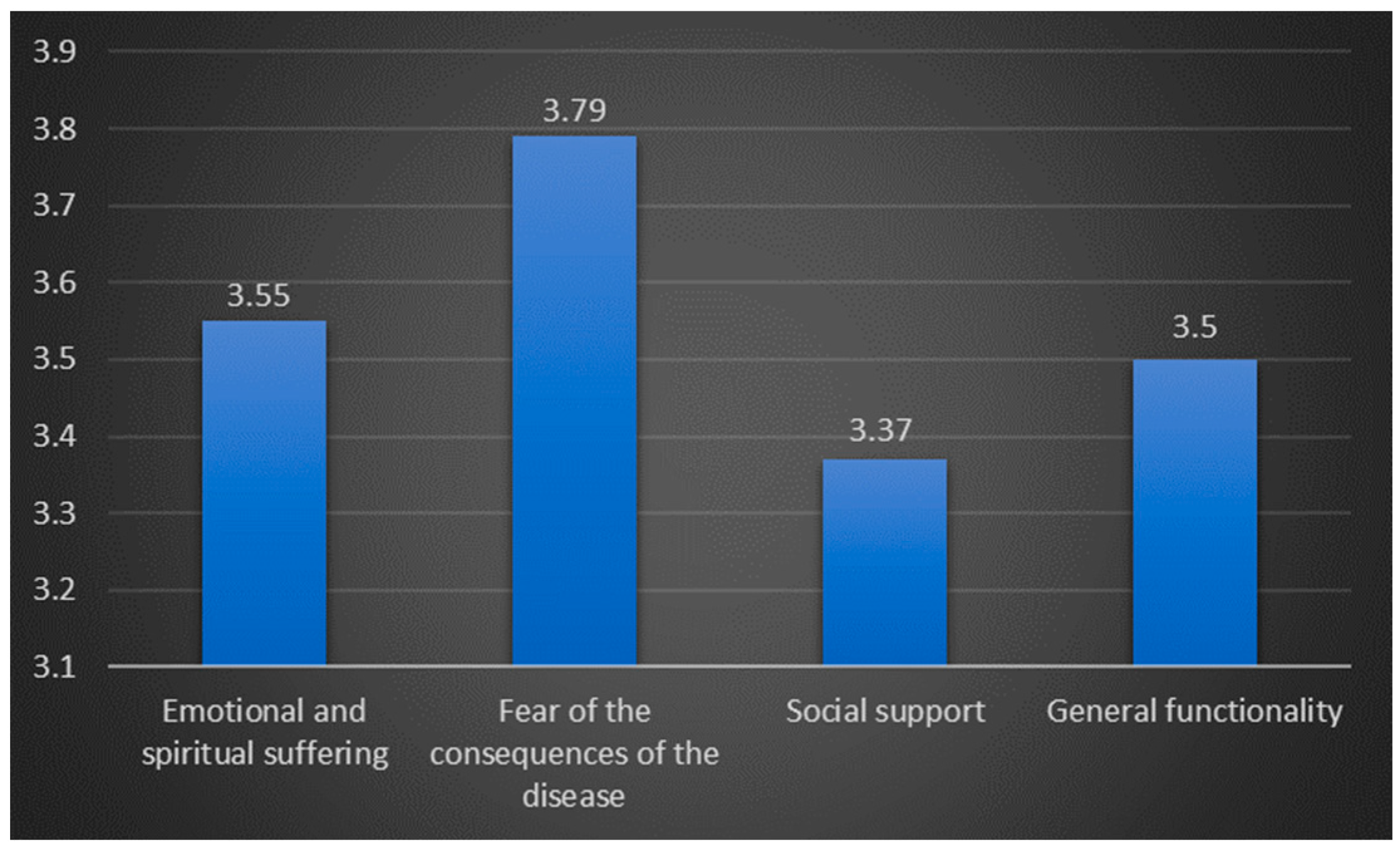

3.2. Psychological, Social, and Spiritual Needs of Palliative Patients Questionnaire

3.2.1. Content and Face Validity

3.2.2. Construct Validity and Reliability

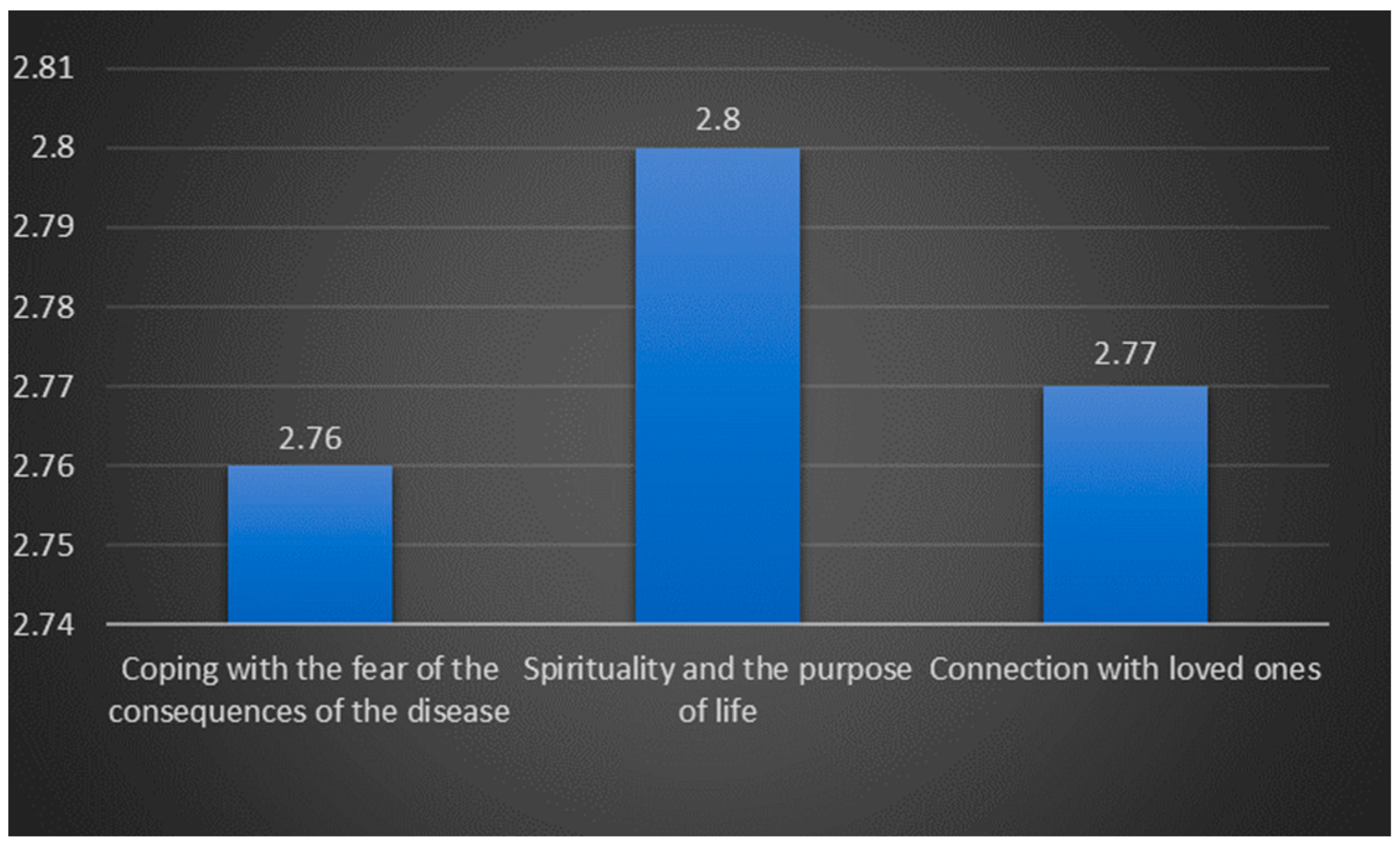

3.3. Effectiveness in Coping with the Psychological, Social, and Spiritual Challenges of Palliative Care Patients

3.3.1. Content and Face Validity

3.3.2. Construct Validity and Reliability

3.4. Nurses Assessment of the Psychological, Social, and Spiritual Needs of Palliative Patients’ Questionnaire and Effectiveness in Coping with the Psychological, Social, and Spiritual Challenges of Palliative Care Patients

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clark, D. ‘Total pain’, disciplinary power and the body in the work of Cicely Saunders, 1958–1967. Soc. Sci. Med. 1999, 49, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, C. The evolution of palliative care. J. R. Soc. Med. 2001, 94, 430–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, F.; Nunes, R. The interface between psychology and spirituality in palliative care. J. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulmasy, D.P. Spiritual issues in the care of dying patients: “…it’s okay between me and god”. JAMA 2006, 296, 1385–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lormans, T.; de Graaf, E.; van de Geer, J.; van der Baan, F.; Leget, C.; Teunissen, S. Toward a socio-spiritual approach? A mixed-methods systematic review on the social and spiritual needs of patients in the palliative phase of their illness. Palliat. Med. 2021, 35, 1071–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobanski, P.Z.; Alt-Epping, B.; Currow, D.C.; Goodlin, S.J.; Grodzicki, T.; Hogg, K.; Janssen, D.J.A.; Johnson, M.J.; Krajnik, M.; Leget, C.; et al. Palliative care for people living with heart failure: European Association for Palliative Care Task Force expert position statement. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 116, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.; Pang, N.; Shiu, V.; Chan, C. The understanding of spirituality and the potential role of spiritual care in end-of-life and palliative care: A meta-study of qualitative research. Palliat. Med. 2010, 24, 753–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balboni, T.A.; VanderWeele, T.J.; Doan-Soares, S.D.; Long, K.N.G.; Ferrell, B.R.; Fitchett, G.; Koenig, H.G.; Bain, P.A.; Puchalski, C.; Steinhauser, K.E.; et al. Spirituality in Serious Illness and Health. JAMA 2022, 328, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finucane, A.M.; Swenson, C.; MacArtney, J.I.; Perry, R.; Lamberton, H.; Hetherington, L.; Graham-Wisener, L.; Murray, S.A.; Carduff, E. What makes palliative care needs “complex”? A multisite sequential explanatory mixed methods study of patients referred for specialist palliative care. BMC Palliat. Care 2021, 20, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Malley, K.; Blakley, L.; Ramos, K.; Torrence, N.; Sager, Z. Mental healthcare and palliative care: Barriers. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2021, 11, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, B.; Rodrigues, P.P.; Higginson, I.J.; Ferreira, P.L. Determining the prevalence of palliative needs and exploring screening accuracy of depression and anxiety items of the integrated palliative care outcome scale—A multi-centre study. BMC Palliat. Care 2020, 19, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamer, M.; Chida, Y.; Molloy, G.J. Psychological distress and cancer mortality. J. Psychosom. Res. 2009, 66, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, M.; Dowrick, C.; Lloyd-Williams, M. What can we learn about the spiritual needs of palliative care patients from the research literature? J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2012, 43, 1105–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E.J. Spiritual Screening, History, and Assessment. In Oxford Textbook of Palliative Nursing; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 432–446. [Google Scholar]

- Phelps, A.C.; Lauderdale, K.E.; Alcorn, S.; Dillinger, J.; Balboni, M.T.; Van Wert, M.; VanderWeele, T.J.; Balboni, T.A. Addressing spirituality within the care of patients at the end of life: Perspectives of patients with advanced cancer, oncologists, and oncology nurses. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 2538–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumstein-Shaha, M.; Ferrell, B.; Economou, D. Nurses’ response to spiritual needs of cancer patients. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2020, 48, 101792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryschek, G.; Machado, D.A.; Otuyama, L.J.; Goodwin, C.; Lima, M.C.P. Spiritual coping and psychological symptoms as the end approaches: A closer look on ambulatory palliative care patients. Psychol. Health Med. 2020, 25, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, H.G. Research on religion, spirituality, and mental health: A review. Can. J. Psychiatry 2009, 54, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanasamy, A. Spiritual coping mechanisms in chronically ill patients. Br. J. Nurs. 2002, 11, 1461–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steglitz, J.; Ng, R.; Mosha, J.S.; Kershaw, T. Divinity and distress: The impact of religion and spirituality on the mental health of HIV-positive adults in Tanzania. AIDS Behav. 2012, 16, 2392–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moens, K.; Higginson, I.J.; Harding, R. Are there differences in the prevalence of palliative care-related problems in people living with advanced cancer and eight non-cancer conditions? A systematic review. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2014, 48, 660–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibnall, J.T.; Videen, S.D.; Duckro, P.N.; Miller, D.K. Psychosocial— spiritual correlates of death distress in patients with life-threatening medical conditions. Palliat. Med. 2002, 16, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Molassiotis, A.; Chung, B.P.M.; Tan, J.Y. Unmet care needs of advanced cancer patients and their informal caregivers: A systematic review. BMC Palliat. Care 2018, 17, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, B.; Bainbridge, D.; Bryant, D.; Tan Toyofuku, S.; Seow, H. What matters most for end-of-life care? Perspectives from community-based palliative care providers and administrators. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.A.; Chun, J.; Kim, H.Y. Hospice palliative care nurses’ perceptions of spiritual care and their spiritual care competence: A mixed-methods study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 961–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisesrith, W.; Sukcharoen, P.; Sripinkaew, K. Spiritual Care Needs of Terminal Ill Cancer Patients. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2021, 22, 3773–3779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, F.; Pereira, C.; Rego, G.; Nunes, R. The Psychological and Spiritual Dimensions of Palliative Care: A Descriptive Systematic Review. Neuropsychiatry 2018, 8, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchalski, C.; Romer, A.L. Taking a spiritual history allows clinicians to understand patients more fully. J. Palliat. Med. 2000, 3, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandarajah, G.; Hight, E. Spirituality and medical practice: Using the HOPE questions as a practical tool for spiritual assessment. Am. Fam. Physician 2001, 63, 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Maugans, T.A. The SPIRITual history. Arch. Fam. Med. 1996, 5, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.K.; Astrow, A.B.; Texeira, K.; Sulmasy, D.P. The Spiritual Needs Assessment for Patients (SNAP): Development and validation of a comprehensive instrument to assess unmet spiritual needs. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2012, 44, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, A.; Girgis, A.; Currow, D.; Lecathelinais, C. Development of the palliative care needs assessment tool (PC-NAT) for use by multi-disciplinary health professionals. Palliat. Med. 2008, 22, 956–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrvatska Komora Medicinskih Sestara. Kompetencije Medicinske Sestre u Specijalističkoj Palijativnoj Skrbi; Hrvatska Komora Medicinskih Sestara: Zagreb, Croatia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ministarstvo Zdravstva Republike Hrvatske. Nacionalni Plan Razvoja Palijativne Skrbi u Republici Hrvatskoj 2017–2020; Ministarstvo Zdravstva Republike Hrvatske: Zagreb, Croatia, 2017.

- Pruthi, M.; Bhatnagar, S.; Indrayan, A.; Chanana, G. The Palliative Care Knowledge Questionnaire-Basic (PCKQ-B): Development and Validation of a Tool to Measure Knowledge of Health Professionals about Palliative Care in India. Indian J. Palliat. Care 2022, 28, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewtz, C.; Muscheites, W.; Kriesen, U.; Grosse-Thie, C.; Kragl, B.; Panse, J.; Aoun, S.; Cella, D.; Junghanss, C. Questionnaires measuring quality of life and satisfaction of patients and their relatives in a palliative care setting-German translation of FAMCARE-2 and the palliative care subscale of FACIT-Pal. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2018, 7, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ansari, A.M.; Suroor, S.N.; AboSerea, S.M.; Abd-El-Gawad, W.M. Development of palliative care attitude and knowledge (PCAK) questionnaire for physicians in Kuwait. BMC Palliat. Care 2019, 18, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osse, B.H.; Vernooij, M.J.; Schadé, E.; Grol, R.P. Towards a new clinical tool for needs assessment in the palliative care of cancer patients: The PNPC instrument. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2004, 28, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchalski, C.M.; Vitillo, R.; Hull, S.K.; Reller, N. Improving the spiritual dimension of whole person care: Reaching national and international consensus. J. Palliat. Med. 2014, 17, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulmasy, D.P. A biopsychosocial-spiritual model for the care of patients at the end of life. Gerontologist 2002, 42 (Suppl. S3), 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, J. The Importance of Holistic Care at the End of Life. Ulst. Med. J. 2017, 86, 143–144. [Google Scholar]

- Gelegjamts, D.; Gaalan, K.; Burenerdene, B. Ethics in Palliative Care. In New Research in Nursing—Education and Practice; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti, J. How to Become a Palliative Care Nurse; NurseJournal. Available online: https://nursejournal.org/careers/palliative-care-nurse/ (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Nguyen, D.T.; Kim, E.S.; Rodriguez de Gil, P.; Kellermann, A.; Chen, Y.-H.; Kromrey, J.D.; Bellara, A. Parametric tests for two population means under normal and non-normal distributions. J. Mod. Appl. Stat. Methods 2016, 15, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, M.; Lecavalier, L. Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in developmental disability psychological research. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2010, 40, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M.S. A Note on the Multiplying Factors for Various χ2 Approximations. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 1954, 16, 296–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, C. The Management of Terminal Malignant Disease, 1st ed.; Edward Aenold: London, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Block, S.D. Psychological issues in end-of-life care. J. Palliat. Med. 2006, 9, 751–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, P. Spirituality, religion and palliative care. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2014, 3, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, E.; Dobson, K. Psychology, spirituality, and end-of-life care: An ethical integration? Can. Psychol./Psychol. Can. 2006, 47, 284–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rome, R.B.; Luminais, H.H.; Bourgeois, D.A.; Blais, C.M. The role of palliative care at the end of life. Ochsner J. 2011, 11, 348–352. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, K.A.; Kilby, C.J. Fear, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in palliative care. In Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine; Oxford Press: Oxford, UK, 2021; pp. 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, J.A.; Maytal, G.; Stern, T.A. Clinical Challenges to the Delivery of End-of-Life Care. Prim. Care Companion J. Clin. Psychiatry 2006, 8, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy | 0.952 | |

|---|---|---|

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi-Square | 11.455.736 |

| df | 1.378 | |

| p | <0.001 | |

| In Your Opinion, to What Extent Do Most Palliative Patients Experience These Problems? | I Emotional and Spiritual Suffering | II Fear of the Consequences of the Disease | III Social Support | IV General Functionality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Eigenvalues | 26.31 | 3.63 | 2.52 | 1.75 |

| % of Variance | 49.65% | 6.85% | 4.76% | 3.31% |

| Cumulative % | 49.65% | 56.5% | 61.26% | 64.56% |

| Rotation Sums of Squared | 10.7 | 3 | 9.41 | 5.01 |

| % of Variance | 20.19% | 17.76% | 9.46% | 8.13% |

| Cumulative % | 20.19% | 37.96% | 47.42% | 55.55% |

| Item Loadings | ||||

| P1 | 0.497 | |||

| P2 | 0.585 | |||

| P3 | 0.625 | |||

| P4 | 0.735 | |||

| P5 | 0.771 | |||

| P6 | 0.605 | |||

| P7 | 0.728 | |||

| P8 | 0.677 | |||

| P9 | 0.515 | |||

| P10 | 0.491 | |||

| P11 | 0.516 | |||

| P12 | 0.450 | |||

| P13 | 0.617 | |||

| P14 | 0.692 | |||

| P15 | 0.594 | |||

| P16 | 0.616 | |||

| P17 | 0.613 | |||

| P18 | 0.741 | |||

| P19 | 0.518 | |||

| P20 | 0.709 | |||

| P21 | 0.766 | |||

| P22 | 0.800 | |||

| P23 | 0.609 | |||

| P24 | 0.827 | |||

| P25 | 0.781 | |||

| P26 | 0.779 | |||

| P27 | 0.702 | |||

| P28 | 0.502 | |||

| P29 | 0.446 | |||

| P30 | 0.492 | |||

| P31 | 0.516 | |||

| P32 | 0.552 | |||

| P33 | 0.562 | |||

| P34 | 0.570 | |||

| P35 | 0.578 | |||

| P36 | 0.579 | |||

| P37 | 0.432 | |||

| P38 | 0.562 | |||

| P39 | 0.574 | |||

| P40 | 0.606 | |||

| P41 | 0.620 | |||

| P42 | 0.611 | |||

| P43 | 0.710 | |||

| P44 | 0.728 | |||

| P45 | 0.694 | |||

| P46 | 0.778 | |||

| P47 | 0.720 | |||

| P48 | 0.740 | |||

| P49 | 0.663 | |||

| P50 | 0.565 | |||

| P51 | 0.632 | |||

| P52 | 0.721 | |||

| P53 | 0.713 |

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy | 0.963 | |

|---|---|---|

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi-Square | 14.189.599 |

| df | 1.378 | |

| p | <0.001 | |

| In Your Opinion, to What Extent Are the Psychological, Social, and Spiritual Problems of Palliative Patients Being Addressed? | I Coping with the Fear of the Consequences of the Disease | II Spirituality and the Purpose of Life | III Connection with Loved Ones |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Eigenvalues | 33.190 | 2.039 | 1.853 |

| % of Variance | 62.623 | 3.848 | 3.496 |

| Cumulative % | 62.623 | 66.470 | 69.966 |

| Rotation Sums of Squared | 12.934 | 12.084 | 12.064 |

| % of Variance | 24.404 | 22.801 | 22.762 |

| Cumulative % | 24.404 | 47.204 | 69.966 |

| Item Loadings | |||

| SN1 | 0.815 | ||

| SN2 | 0.808 | ||

| SN3 | 0.789 | ||

| SN4 | 0.781 | ||

| SN5. | 0.723 | ||

| SN6 | 0.674 | ||

| SN7 | 0.673 | ||

| SN8 | 0.662 | ||

| SN9 | 0.657 | ||

| SN10 | 0.634 | ||

| SN11 | 0.630 | ||

| SN12 | 0.629 | ||

| SN13 | 0.608 | ||

| SN14 | 0.583 | ||

| SN15 | 0.581 | ||

| SN16 | 0.570 | ||

| SN17 | 0.531 | ||

| SN18 | 0.777 | ||

| SN19 | 0.719 | ||

| SN20 | 0.691 | ||

| SN21 | 0.676 | ||

| SN22 | 0.666 | ||

| SN23 | 0.665 | ||

| SN24 | 0.655 | ||

| SN25 | 0.652 | ||

| SN26 | 0.650 | ||

| SN27 | 0.648 | ||

| SN28 | 0.637 | ||

| SN29 | 0.627 | ||

| SN30 | 0.623 | ||

| SN31 | 0.547 | ||

| SN32 | 0.567 | ||

| SN33 | 0.563 | ||

| SN34 | 0.553 | ||

| SN35 | 0.511 | ||

| SN36 | 0.709 | ||

| SN37 | 0.692 | ||

| SN38 | 0.690 | ||

| SN39 | 0.688 | ||

| SN40 | 0.684 | ||

| SN41 | 0.680 | ||

| SN42 | 0.657 | ||

| SN43 | 0.650 | ||

| SN44 | 0.640 | ||

| SN45 | 0.629 | ||

| SN46 | 0.624 | ||

| SN47 | 0.616 | ||

| SN48 | 0.612 | ||

| SN49 | 0.610 | ||

| SN50 | 0.577 | ||

| SN51 | 0.545 | ||

| SN52 | 0.354 | ||

| SN53 | 0.344 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Antičević, V.; Ćurković, A.; Lušić Kalcina, L. Validation of Two Questionnaires Assessing Nurses’ Perspectives on Addressing Psychological, Social, and Spiritual Challenges in Palliative Care Patients. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 2415-2429. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14030179

Antičević V, Ćurković A, Lušić Kalcina L. Validation of Two Questionnaires Assessing Nurses’ Perspectives on Addressing Psychological, Social, and Spiritual Challenges in Palliative Care Patients. Nursing Reports. 2024; 14(3):2415-2429. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14030179

Chicago/Turabian StyleAntičević, Vesna, Ana Ćurković, and Linda Lušić Kalcina. 2024. "Validation of Two Questionnaires Assessing Nurses’ Perspectives on Addressing Psychological, Social, and Spiritual Challenges in Palliative Care Patients" Nursing Reports 14, no. 3: 2415-2429. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14030179

APA StyleAntičević, V., Ćurković, A., & Lušić Kalcina, L. (2024). Validation of Two Questionnaires Assessing Nurses’ Perspectives on Addressing Psychological, Social, and Spiritual Challenges in Palliative Care Patients. Nursing Reports, 14(3), 2415-2429. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14030179