Effects of StereoBiCROS on Speech Understanding in Noise and Quality of Life for Asymmetric Sensorineural Hearing Loss

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Patients

2.3. Hearing Evaluation

2.4. Audiological Assessment

2.5. HA Fitting

2.6. Speech in Noise Perception

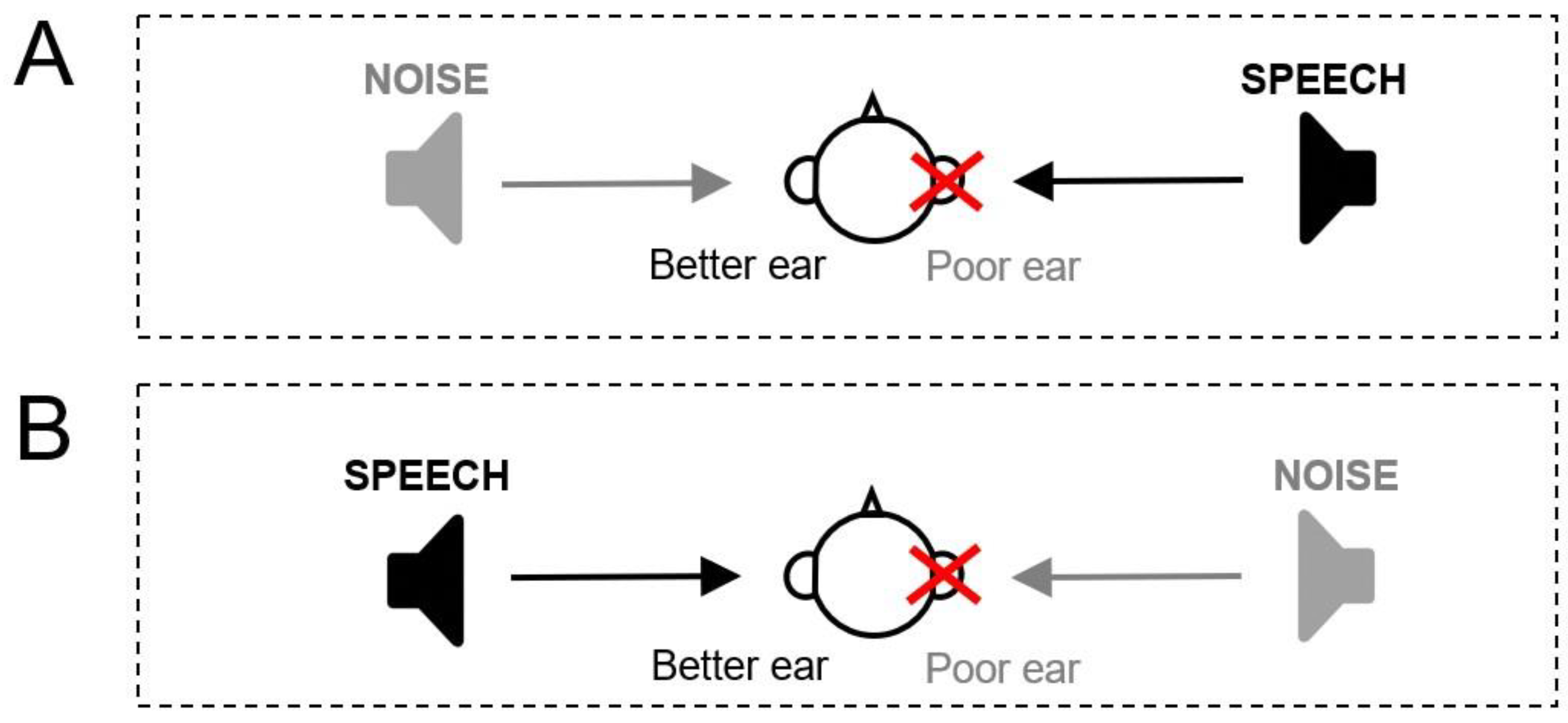

- Dichotic Condition (Figure 3A): Speech is emitted on the ASNHL side and noise to the better ear. Five lists of words are presented at an intensity of 55 dB SPL by varying the noise level from 45 to 65 dB SPL in order to obtain an SNR varying from +10 to −10.

- Reverse-dichotic condition (Figure 3B): Speech is emitted on the side of the better ear and noise on the ASNHL side. Five lists of words are presented at an intensity of 55 dB SPL by varying the noise level from 50 to 70 dB SPL in order to obtain an SNR varying from +5 to −15.

2.7. Subjective Assessment of Hearing Perception

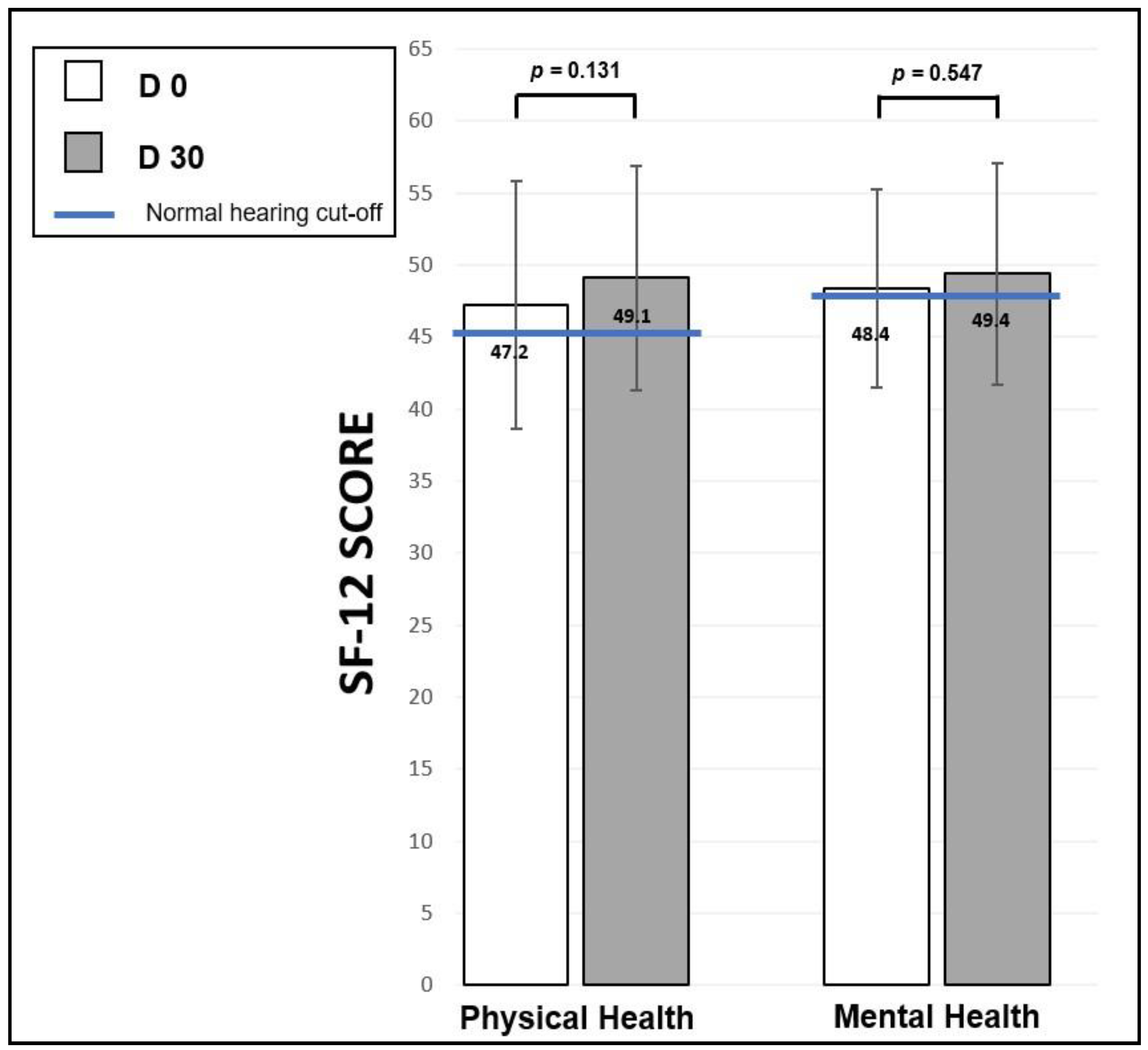

- The SF-12 questionnaire [78], which is an abridged and validated version in French of the SF-36 “Short Form Health Survey” [79]. The SF-12 Health Survey questionnaire was originally developed in the United States to provide a shorter alternative to the SF-36, for use in large-scale health measurement and monitoring efforts in which a 36-item questionnaire was too lengthy and in which the focus was on overall physical and mental health outcomes [80]. SF-12 is a questionnaire that measures generic QoL by exploring a patient’s physical, emotional, and social health. It includes 8 dimensions, like the SF-36 (physical activity, life and relationships with others, physical pain, perceived health, vitality, limitations due to mental state, limitations due to physical condition, and mental health). Although non-specific to hearing, it is widely used in medical studies because it allows one to measure the overall health of an individual without considering any specific pathology. The item selection and validation study were carried out in France and in 9 European countries with 9000 people [78]. In its abridged version, it consists of 12 questions to which the patient answers. A score is given for each answer, and adding all the scores together gives two scores (each scored out of 100): the physical health score and the mental health score. In their 1998 publication, Gandek et al. provide a mean score (and standard deviation) by age groups for the physical and mental health scores for each of the countries studied [78]. A score greater than 50 corresponds to an average QoL, a score between 40 and 49 indicates a slight disability, a score between 30 to 39 a moderate disability, and a score less than 30 a severe disability.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Speech Perception in Noise

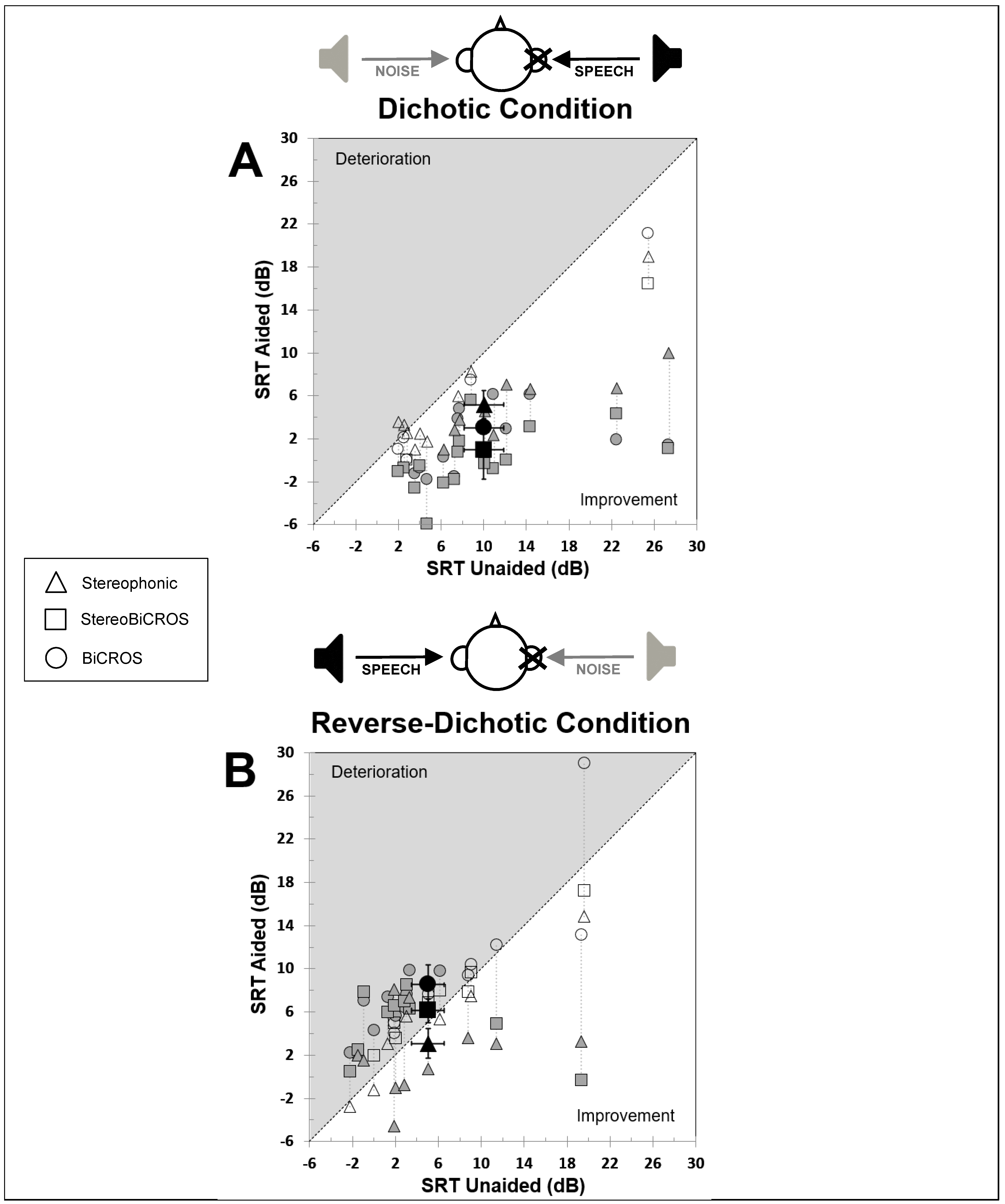

3.2. Dichotic Condition

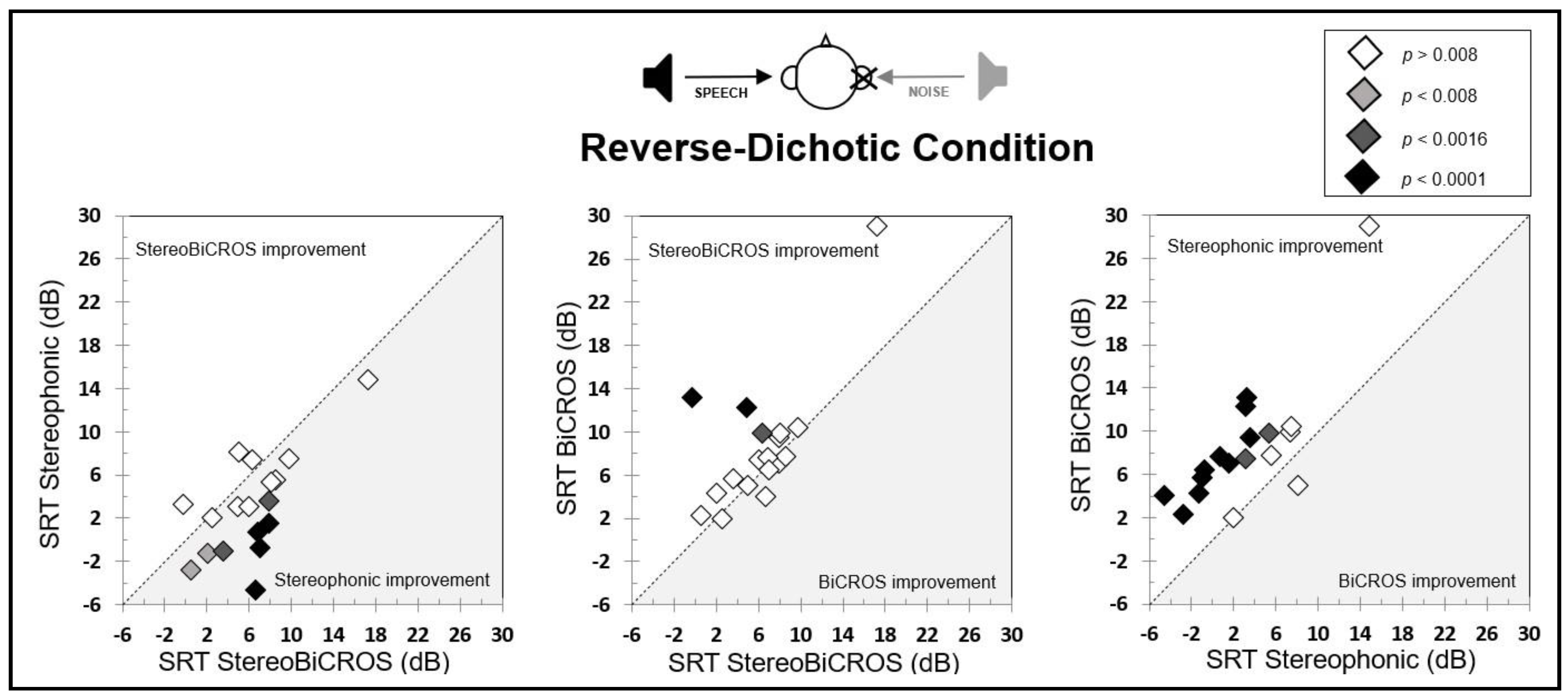

3.3. Reverse-Dichotic Condition

3.4. Cost-Effectiveness Ratio of the Conditions

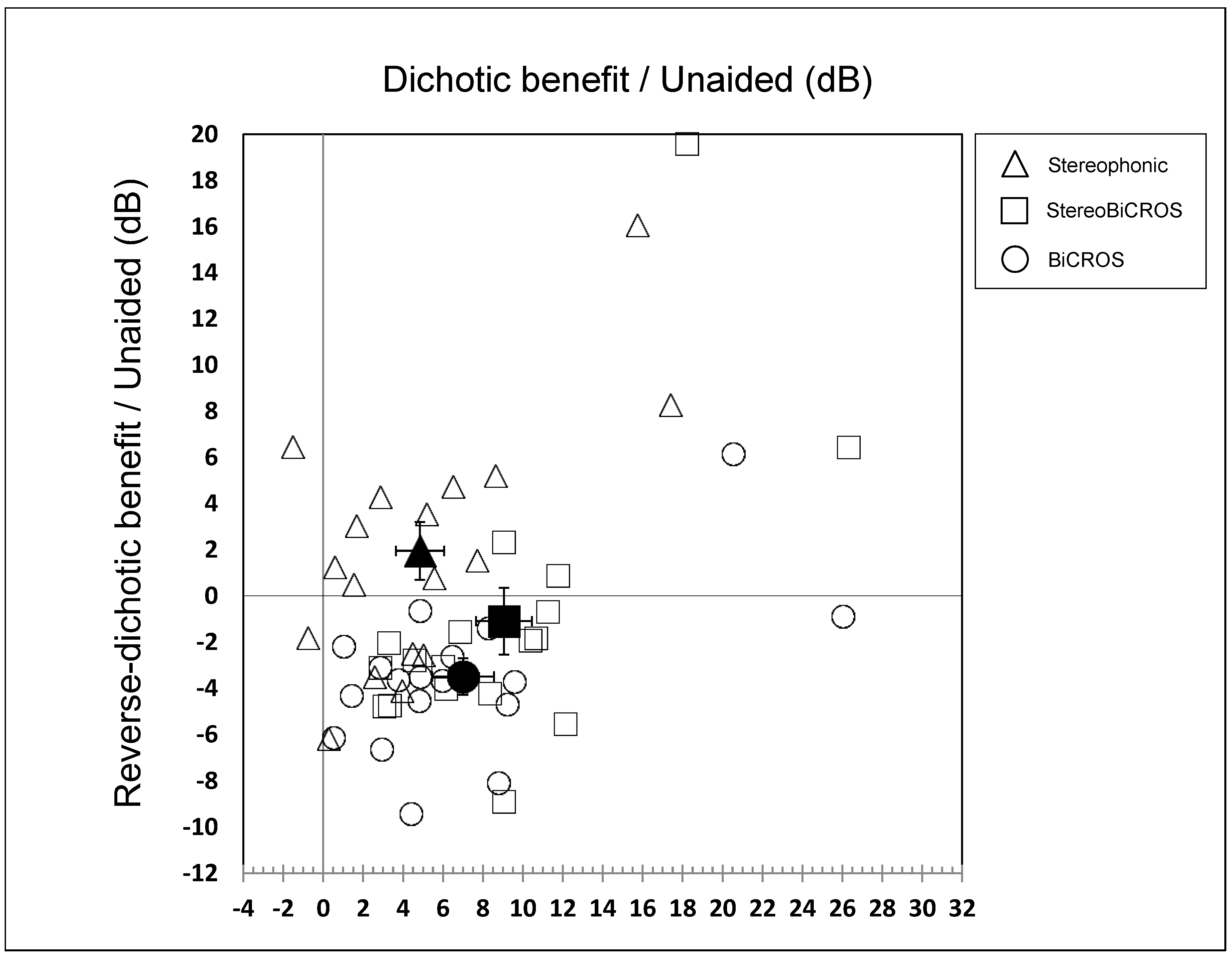

- The BiCROS condition provides a mean improvement of 7.0 ± 1.5 dB in dichotic configuration, which cost a degradation of 3.5 ± 0.8 dB in reverse-dichotic configuration.

- The Stereophonic condition provides a mean improvement of both configurations, with 4.8 ± 1.2 dB in dichotic configuration and 1.9 ± 1.2 dB in reverse-dichotic configuration.

- The StereoBiCROS condition provides a mean improvement of 9.0 ± 1.4 dB in dichotic configuration, which cost a degradation of 1.1 ± 1.4 dB in reverse-dichotic configuration.

3.5. Questionnaire Evaluation

3.5.1. Speech Spatial and Qualities of Hearing Scale (SSQ-15)

3.5.2. Short Form Health Survey (SF-12)

3.6. HA Utilization

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of the Results

4.2. Effectiveness of Current Prosthetic Solutions

- A beneficial effect when the SNR on the side of the poor ear is favorable, i.e., in a dichotic condition.

- A deleterious effect when the SNR on the side of the better ear is favorable, i.e., in a reverse-dichotic condition.

4.3. Effects of StereoBiCROS on Speech Perception in Noise

4.4. Datalogging Utilization

4.5. QoL Questionnaire Evaluation

4.6. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Acronym | Signification |

| AC | Air Conduction |

| ANSI | American National Standards Institute |

| ASNHL | Asymmetric Sensorineural Hearing Loss |

| BAHA | Bone-Anchored Hearing Aid |

| BC | Bone Conduction |

| BiCROS | Bilateral Contralateral Routing of Signal |

| CI | Cochlear Implant |

| CPP | Comité de Protection des Personnes |

| CROS | Contralateral Routing of Signal |

| dB | deciBel |

| HA | Hearing Aid |

| HL | Hearing Level |

| ILD | Interaural Level Difference |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| ITD | Interaural Time Difference |

| PTA | Pure Tone Average |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| REM | Real Ear Measurement |

| SF-12 | 12-Item Short Form Health Survey |

| SF-36 | 36-Item Short Form Health Survey |

| SNR | Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| SPL | Sound Pressure Level |

| SRT | Speech Recognition Thresholds |

| SSD | Single-Sided Deafness |

| SSQ | Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing Scale |

| StereoBiCROS | BiCROS with bilateral amplification (stereophonic) |

| USNHL | Unilateral Sensorineural Hearing Loss |

References

- Augustine, A.M.; Chrysolyte, S.B.; Thenmozhi, K.; Rupa, V. Assessment of auditory and psychosocial handicap associated with unilateral hearing loss among Indian patients. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2013, 65, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, L.; Katiri, R.; Kitterick, P.T. The psychological and social consequences of single-sided deafness in adulthood. Int. J. Audiol. 2018, 57, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillman, T.; Carhart, R. An Expanded Test for Speech Discrimination Utilizing CNC Monosyllabic Words: Northwestern University Auditory Test No. 6; Report SAM-TR-66-55. Brooks Air Force Base; USAF School of Aerospace Medicine, Aerospace Medical Division (AFSC): San Antonio, TX, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Gantz, B.J.; Tyler, R.S.; Rubinstein, J.T.; Wolaver, A.; Lowder, M.; Abbas, P.; Brown, C.; Hughes, M.; Preece, J.P. Binaural cochlear implants placed during the same operation. Otol. Neurotol. 2002, 23, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoen, F.; Mueller, J.; Helms, J.; Nopp, P. Sound localization and sensitivity to interaural cues in bilateral users of the Med-El Combi 40/40+cochlear implant system. Otol. Neurotol. 2005, 26, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markides, A. (Ed.) Advantages of binaural over monaural hearing. In Binaural Hearing Aids; Academic Press: London, UK, 1977; pp. 276–298. [Google Scholar]

- Gulick, W.; Gescheider, G.; Frisina, R. Hearing; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Laszig, R.; Aschendorff, A.; Stecker, M.; Müller-Deile, J.; Maune, S.; Dillier, N.; Weber, B.; Hey, M.; Begall, K.; Lenarz, T.; et al. Benefits of bilateral electrical stimulation with the nucleus cochlear implant in adults: 6-month postoperative results. Otol. Neurotol. 2004, 25, 958–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buss, E.; Pillsbury, H.C.; Buchman, C.A.; Pillsbury, C.H.; Clark, M.S.; Haynes, D.S.; Labadie, R.F.; Amberg, S.; Roland, P.S.; Kruger, P.; et al. Multicenter U.S. bilateral MED-EL cochlear implantation study: Speech perception over the first year of use. Ear Hear. 2008, 29, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agterberg, M.J.; Hol, M.K.; Van Wanrooij, M.M.; Van Opstal, A.J.; Snik, A.F. Single-sided deafness and directional hearing: Contribution of spectral cues and high-frequency hearing loss in the hearing ear. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, B.; Upfold, L.; Taylor, A. Self reported hearing difficulties following excision of vestibular schwannoma. Int. J. Audiol. 2008, 47, 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, C.E.; Eby, T.L. The current status of audiologic rehabilitation for profound unilateral sensorineural hearing loss. Laryngoscope 2010, 120, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avan, P.; Giraudet, F.; Büki, B. Importance of binaural hearing. Audiol. Neurootol. 2015, 20, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, S.; Aschendorff, A.; Laszig, R.; Beck, R.; Schild, C.; Kroeger, S.; Ihorst, G.; Wesarg, T. Comparison of pseudobinaural hearing to real binaural hearing rehabilitation after cochlear implantation in patients with unilateral deafness and tinnitus. Otol. Neurotol. 2011, 32, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, R.; Stelzig, Y.; Nopp, P.; Schleich, P. Audiological results with cochlear implants for single-sided deafness. HNO 2011, 59, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giolas, T.G.; Wark, D.J. Communication problems associated with unilateral hearing loss. J. Speech Hear. Disord. 1967, 32, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargent, E.W.; Herrmann, B.; Hollenbeak, C.S.; Bankaitis, A.E. The minimum speech test battery in profound unilateral hearing loss. Otol. Neurotol. 2001, 22, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, S.A.; Yeung, P.; Daudia, A.; Gatehouse, S.; O’Donoghue, G.M. Spatial hearing disability after acoustic neuroma removal. Laryngoscope 2007, 117, 1648–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatehouse, S.; Noble, W. The speech, spatial and qualities of hearing scale (SSQ). Int. J. Audiol. 2004, 43, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, N.Y.; Firszt, J.B.; Reeder, R.M. Effects of unilateral input and mode of hearing in the better ear: Self-reported performance using the speech, spatial and qualities of hearing scale. Ear Hear. 2014, 35, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitterick, P.T.; Smith, S.N.; Lucas, L. Hearing Instruments for Unilateral Severe-to-Profound Sensorineural Hearing Loss in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ear Hear. 2016, 37, 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Newman, C.W.; Jacobson, G.P.; Hug, G.A.; Sandridge, S.A. Perceived hearing handicap of patients with unilateral or mild hearing loss. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1997, 106, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiossoine-Kerdel, J.A.; Baguley, D.M.; Stoddart, R.L.; Moffat, D.A. An investigation of the audiologic handicap associated with unilateral sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Otol. Neurotol. 2000, 21, 645–651. [Google Scholar]

- Parving, A.; Parving, I.; Erlendsson, A.; Christensen, B. Some experiences with hearing disability/handicap and quality of life measures. Audiology 2001, 40, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisolm, T.H.; Johnson, C.E.; Danhauer, J.L.; Portz, L.J.; Abrams, H.B.; Lesner, S.; McCarthy, P.A.; Newman, C.W. A systematic review of health-related quality of life and hearing aids: Final report of the American Academy of Audiology Task Force on the Health-Related Quality of Life Benefits of Amplification in Adults. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2007, 18, 151–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Härkönen, K.; Kivekäs, I.; Rautiainen, M.; Kotti, V.; Vasama, J.P. Quality of Life and Hearing Eight Years After Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss. Laryngoscope 2017, 127, 927–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaranta, N.; Bartoli, R.; Quaranta, A. Cochlear implants: Indications in groups of patients with borderline indications. A review. Acta Oto Laryngol. Suppl. 2004, 124, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wie, O.B.; Pripp, A.H.; Tvete, O. Unilateral deafness in adults: Effects on communication and social interaction. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2010, 119, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ramos Macías, A.; Falcón González, J.C.; Manrique, M.; Morera, C.; García-Ibáñez, L.; Cenjor, C.; Coudert-Koall, C.; Killian, M. Cochlear implants as a treatment option for unilateral hearing loss, severe tinnitus and hyperacusis. Audiol. Neurootol. 2015, 20, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firszt, J.B.; Holden, L.K.; Reeder, R.M.; Cowdrey, L.; King, S. Cochlear implantation in adults with asymmetric hearing loss. Ear Hear. 2012, 33, 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, J.F.; Dai, J.S.; Wang, N.Y. Effect of cochlear implantation on sound localization for patients with unilateral sensorineural hearing loss. Chin. J. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016, 51, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arndt, S.; Laszig, R.; Aschendorff, A.; Hassepass, F.; Beck, R.; Wesarg, T. Cochlear implant treatment of patients with single-sided deafness or asymmetric hearing loss. HNO 2017, 65, 98–108. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firszt, J.B.; Reeder, R.M.; Holden, L.K. Unilateral Hearing Loss: Understanding Speech Recognition and Localization Variability-Implications for Cochlear Implant Candidacy. Ear Hear. 2017, 38, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Buss, E.; Dillon, M.T.; Rooth, M.A.; King, E.R.; Deres, E.J.; Buchman, C.A.; Pillsbury, H.C.; Brown, K.D. Effects of Cochlear Implantation on Binaural Hearing in Adults with Unilateral Hearing Loss. Trends Hear. 2018, 22, 2331216518771173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Thompson, N.J.; Brown, K.D.; Buss, E.; Rooth, M.A.; Richter, M.E.; Dillon, M.T. Long-Term Binaural Hearing Improvements for Cochlear Implant Users with Asymmetric Hearing Loss. Laryngoscope 2023, 133, 1480–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venail, F.; Sicard, M.; Piron, J.P.; Levi, A.; Artieres, F.; Uziel, A.; Mondain, M. Reliability and complications of 500 consecutive cochlear implantations. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2008, 134, 1276–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farinetti, A.; Ben Gharbia, D.; Mancini, J.; Roman, S.; Nicollas, R.; Triglia, J.M. Cochlear implant complications in 403 patients: Comparative study of adults and children and review of the literature. Eur. Ann Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2014, 131, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinnon, B.J. Cost effectiveness of cochlear implants. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2014, 22, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theunisse, H.J.; Pennings, R.J.E.; Kunst, H.P.M.; Mulder, J.J.; Mylanus, E.A.M. Risk factors for complications in cochlear implant surgery. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2018, 275, 895–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marx, M.; Costa, N.; Lepage, B.; Taoui, S.; Molinier, L.; Deguine, O.; Fraysse, B. Cochlear implantation as a treatment for single-sided deafness and asymmetric hearing loss: A randomized controlled evaluation of cost-utility. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord. 2019, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, C.E.; Hamadain, E.; Galster, J.A.; Johnson, M.F.; Spankovich, C.; Windmill, I. Outcomes of Hearing Aid Use by Individuals with Unilateral Sensorineural Hearing Loss (USNHL). J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2017, 28, 941–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harford, E.; Barry, J. A rehabilitative approach to the problem of unilateral hearing impairment: The contralateral routing of signals (CROS). J. Speech Hear. Disord. 1965, 30, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harford, E.; Dodds, E. The clinical application of CROS: A hearing aid for unilateral deafness. Arch. Otolaryngol. 1966, 83, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, S.L., III; Marcus, A.; Digges, E.N.; Gillman, N.; Silverstein, H. Assessment of patient satisfaction with various configurations of digital CROS and BiCROS hearing aids. Ear Nose Throat J. 2006, 85, 427–430,442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotterman, S.H.; Kasten, R.N. Examination of the CROS type hearing aid. J. Speech Hear. Res. 1971, 14, 416–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Dot, J.; Hickson, L.M.; O’Connell, B. Speech perception in noise with BiCROS hearing aids. Scand. Audiol. 1992, 21, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niparko, J.K.; Cox, K.M.; Lustig, L.R. Comparison of the bone anchored hearing aid implantable hearing device with contralateral routing of offside signal amplification in the rehabilitation of unilateral deafness. Otol. Neurotol. 2003, 24, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosman, A.J.; Hol, M.K.; Snik, A.F.; Mylanus, E.A.; Cremers, C.W. Bone-anchored hearing aids in unilateral inner ear deafness. Acta Otolaryngol. 2003, 123, 258–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.M.; Bowditch, S.; Anderson, M.J.; May, B.; Cox, K.M.; Niparko, J.K. Amplification in the rehabilitation of unilateral deafness: Speech in noise and directional hearing effects with bone-anchored hearing and contralateral routing of signal amplification. Otol. Neurotol. 2006, 27, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hol, M.K.; Kunst, S.J.; Snik, A.F.; Bosman, A.J.; Mylanus, E.A.; Cremers, C.W. Bone-anchored hearing aids in patients with acquired and congenital unilateral inner ear deafness (Baha CROS): Clinical evaluation of 56 cases. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2010, 119, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuk, F.; Korhonen, P.; Crose, B.; Lau, C. CROS your heart: Renewed hope for people with asymmetric hearing losses. Hear. Rev. 2014, 21, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wazen, J.J.; Ghossaini, S.N.; Spitzer, J.B.; Kuller, M. Localization by unilateral BAHA users. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2005, 132, 928–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, N.G.; Moon, I.J.; Byun, H.; Jin, S.H.; Park, H.; Jang, K.S.; Cho, Y.S. Clinical effectiveness of wireless CROS (contralateral routing of offside signals) hearing aids. Eur. Arch. Oto Rhino Laryngol. 2014, 272, 2213–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuk, F.; Seper, E.; Lau, C.; Crose, B.; Korhonen, P. Effects of Training on the Use of a Manual Microphone Shutoff on a BiCROS Device. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2015, 26, 478–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snapp, H.A.; Hoffer, M.E.; Liu, X.; Rajguru, S.M. Effectiveness in Rehabilitation of Current Wireless CROS Technology in Experienced Bone-Anchored Implant Users. Otol. Neurotol. 2017, 38, 1397–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaneecloo, F.M.; Ruzza, I.; Hanson, J.N.; Gérard, T.; Dehaussy, J.; Cory, M.; Arrouet, C.; Vincent, C. Appareillage mono pseudo stéréophonique par BAHA dans les cophoses unilatérales: À propos de 29 patients. Rev. Laryngol. Otol. Rhinol. 2001, 122, 343–350. [Google Scholar]

- Snapp, H. Nonsurgical Management of Single-Sided Deafness: Contralateral Routing of Signal. J. Neurol. Surg. B Skull Base 2019, 80, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potier, M.; Gallego, S.; Fournier, P.; Marx, M.; Noreña, A. Amplification of the poorer ear by StereoBiCROS in case of asymmetric sensorineural hearing loss: Effect on tinnitus. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1141096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lefeuvre, J.; Gargula, S.; Boulet, M.; Potier, M.; Ayache, D.; Daval, M. Active TriCROS: A Simultaneous Stimulation With a (Bi)CROS System and a Hearing Aid in the Worst Ear for Severely Asymmetrical Hearing Loss. Otol. Neurotol. 2024, 45, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hable, L.A.; Brown, K.M.; Gudmundsen, G.I. CROS-PLUS: A physical CROS system. Hear. Instr. 1990, 41, 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Carhart, R.; Jerger, J. Preferred method for clinical determination of pure-tone thresholds. J. Speech Hear. Disord. 1959, 24, 330–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, J.E. Audiométrie Vocale: Les Epreuves D’Intelligibilité et Leurs Applications au Diagnostic, à L’Expertise et à la Correction Prothétique des Surdités; Maloine: Paris, France, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau International d’Audiophonologie (BIAP). Audiometric Classification of Hearing Impairments. Recommendation 02/1; BIAP: Liege, Belgium, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Moulin, A.; Vergne, J.; Gallego, S.; Micheyl, C. A New Speech, Spatial, and Qualities of Hearing Scale Short-Form: Factor, Cluster, and Comparative Analyses. Ear Hear. 2019, 40, 938–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demeester, K.; Topsakal, V.; Hendrickx, J.J.; Fransen, E.; van Laer, L.; Van Camp, G.; Van de Heyning, P.; van Wieringen, A. Hearing disability measured by the speech, spatial, and qualities of hearing scale in clinically normal-hearing and hearing-impaired middle-aged persons, and disability screening by means of a reduced SSQ (the SSQ5). Ear Hear. 2012, 33, 615–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.J.; An, Y.H.; Choi, J.W.; Park, M.K.; Ahn, J.H.; Lee, S.H.; Park, K.H.; Cheon, B.C.; Choi, B.Y.; Cho, Y.S.; et al. Standardization for a Korean version of the Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing Scale: Study of validity and reliability. Korean J. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2017, 60, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiessling, J.; Grugel, L.; Meister, G.; Meis, M. Übertragung der Fragebögen SADL, ECHO und SSQ ins Deutsche und deren Evaluation. German translations of questionnaires SADL, ECHO and SSQ and their evaluation. Z. Audiol. 2011, 50, 6–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gonsalez ECde, M.; Almeida, K. Cross-cultural adaptation of the Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing Scale (SSQ) to Brazilian Portuguese. Audiol. Commun. Res. 2015, 20, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akeroyd, M.A.; Guy, F.H.; Harrison, D.L.; Suller, S.L. A factor analysis of the SSQ (Speech, Spatial, and Qualities of Hearing Scale). Int. J. Audiol. 2014, 53, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, W.; Gatehouse, S. Effects of bilateral versus unilateral hearing aid fitting on abilities measured by the speech, spatial, and qualities of hearing scale (SSQ). Int. J. Audiol. 2006, 45, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlstrom, J.B.; Horwitz, A.R.; Dubno, J.R. Spatial benefit of bilateral hearing aids. Ear Hear. 2009, 30, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobler, S.; Lindblad, A.C.; Olofsson, A.; Hagerman, B. Successful and unsuccessful users of bilateral amplification: Differences and similarities in binaural performance. Int. J. Audiol. 2010, 49, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Most, T.; Adi-Bensaid, L.; Shpak, T.; Sharkiya, S.; Luntz, M. Everyday hearing functioning in unilateral versus bilateral hearing-aid users. Am. J. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Med. Surg. 2012, 33, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, R.S.; Perreau, A.E.; Haihong, J. Validation of the Spatial Hearing Questionnaire. Ear Hear. 2009, 30, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potts, L.G.; Skinner, M.W.; Litovsky, R.A.; Strube, M.J.; Kuk, F. Recognition and localization of speech by adult cochlear implant recipients wearing a digital hearing aid in the non-implanted ear (bimodal hearing). J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2009, 20, 353–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, T.P.C.; Lowther, R.; Cooper, H.; Holder, R.L.; Irving, R.M.; Reid, A.P.; Proops, D.W. The bone-anchored hearing aid in the rehabilitation of single-sided deafness: Experience with 58 patients. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2010, 35, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieringen, A.; de Voecht, K.; Bosman, A.J.; Wouters, J. Functional benefit of the bone-anchored hearing aid with different auditory profiles: Objective and subjective measures. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2011, 36, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandek, B.; Ware, J.E.; Aaronson, N.K.; Apolone, G.; Bjorner, J.B.; Brazier, J.E.; Bullinger, M.; Kaasa, S.; Leplege, A.; Prieto, L.; et al. Crossvalidation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 Health Survey in nine countries: Results from the IQOLA Project. International Quality of Life Assessment. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1998, 51, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.E., Jr.; Sherbourne, C.D. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med. Care 1992, 30, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J., Jr.; Kosinski, M.; Keller, S.D. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med. Care 1996, 34, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, A.; Smith, P.; Ferguson, M.; Stephens, D.; Gianopoulos, I. Acceptability, benefit and costs of early screening for hearing disability: A study of potential screening tests and models. Health Technol. Assess. 2007, 11, 1–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, E.; Edmonds, B.A. A systematic review of studies measuring and reporting hearing aid usage in older adults since 1999: A descriptive summary of measurement tools. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e31831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, M.A.; Kitterick, P.T.; Chong, L.Y.; Edmondson-Jones, M.; Barker, F.; Hoare, D.J. Hearing aids for mild to moderate hearing loss in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 9, CD012023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerger, J.; Silman, S.; Lew, H.L.; Chmiel, R. Case studies in binaural interference: Converging evidence from behavioral and electrophysiologic measures. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 1993, 4, 122–131. [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer, C. Confounding binaural interactions. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 1993, 4, 275–276. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Allen, R.L.; Schwab, B.M.; Cranford, J.L.; Carpenter, M.D. Investigation of binaural interference in normal-hearing and hearing-impaired adults. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2000, 11, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jerger, J.; Silman, S.; Silverman, C.; Emmer, M. Binaural Interference: Quo Vadis? J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2017, 28, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussoi, B.S.S.; Bentler, R.A. Binaural Interference and the Effects of Age and Hearing Loss. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2017, 28, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergen, M. Clinical Implications of Binaural Interference: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Ph.D. Thesis, City University of New York, New York, NY, USA, 2014. Cuny Academic Works. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, D.B.; Yacullo, W.S. Signal-to-noise ratio advantage of binaural hearing aids and directional microphones under different levels of reverberation. J. Speech Hear. Disord. 1984, 49, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freyaldenhoven, M.C.; Plyler, P.N.; Thelin, J.W.; Burchfield, S.B. Acceptance of noise with monaural and binaural amplification. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2006, 17, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, R.M.; Schwartz, K.S.; Noe, C.M.; Alexander, G.C. Preference for one or two hearing AIDS among adult patients. Ear Hear. 2011, 32, 181–197, Erratum in Ear Hear. 2011, 32, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- American Academy of Audiology. American Academy of Clinical Audiology’s Practice Guidelines: Adult Patients with Severe-to-Profound Unilateral Sensorineural Hearing Loss; American Academy of Audiology: Reston, VA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, J.P.; Smit, A.L.; Stegeman, I.; Grolman, W. Review: Bone conduction devices and contralateral routing of sound systems in single-sided deafness. Laryngoscope 2015, 125, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendrich, A.W.; Kroese, T.E.; Peters, J.P.M.; Cattani, G.; Grolman, W. Systematic Review on the Trial Period for Bone Conduction Devices in Single-Sided Deafness: Rates and Reasons for Rejection. Otol. Neurotol. 2017, 38, 632–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molinier, L.; Bocquet, H.; Bongard, V.; Fraysse, B. The economics of cochlear implant management in France: A multicentre analysis. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2009, 10, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noble, W. Gatehouse S: Interaural asymmetry of hearing loss, Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing Scale (SSQ) disabilities, and handicap. Int. J. Audiol. 2004, 43, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, G.; Kleine Punte, A.; De Bodt, M.; Van de Heyning, P. Binaural auditory outcomes in patients with postlingual profound unilateral hearing loss: 3 years after cochlear implantation. Audiol. Neurootol. 2015, 20, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dillon, M.T.; Buss, E.; Rooth, M.A.; King, E.R.; Deres, E.J.; Buchman, C.A.; Pillsbury, H.C.; Brown, K.D. Effect of Cochlear Implantation on Quality of Life in Adults with Unilateral Hearing Loss. Audiol. Neurootol. 2017, 22, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vannson, N.; James, C.; Fraysse, B.; Strelnikov, K.; Barone, P.; Deguine, O.; Marx, M. Quality of life and auditory performance in adults with asymmetric hearing loss. Audiol. Neurootol. 2015, 20, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pai, I.; Kelleher, C.; Nunn, T.; Pathak, N.; Jindal, M.; O’Connor, A.F.; Jiang, D. Outcome of bone-anchored hearing aids for single-sided deafness: A prospective study. Acta Otolaryngol. 2012, 132, 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawes, P.; Munro, K.J.; Kalluri, S.; Edwards, B. Acclimatization to hearing aids. Ear Hear. 2014, 35, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humes, L.E.; Busey, T.A.; Craig, J.; Kewley-Port, D. Are age-related changes in cognitive function driven by age-related changes in sensory processing? Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 2013, 75, 508–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| # Patient | Gender | Age (Years) | Etiology | ASNHL Side | Deafness Duration (Months) | Better Ear PTA (dB HL) | Poorer Ear PTA (dB HL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 73 | Sudden deafness (idiopathic) | R | 189 | 31 | 70 |

| 2 | F | 76 | Sudden deafness | R | 99 | 68 | 83 |

| 3 | M | 69 | Sound trauma | L | 362 | 60 | 102 |

| 4 | F | 62 | Sudden deafness | L | 48 | 33 | 90 |

| 5 | M | 68 | Sudden deafness | R | 118 | 34 | 102 |

| 6 | F | 66 | Sudden deafness (idiopathic) | L | 66 | 43 | 89 |

| 7 | M | 71 | Sudden deafness | L | 109 | 30 | 85 |

| 8 | M | 70 | Work in noise | L | NR | 24 | 70 |

| 9 | F | 73 | Sudden deafness | L | 43 | 62 | 97 |

| 10 | M | 80 | ENT history (infections) | R | 72 | 54 | 70 |

| 11 | F | 80 | Sudden deafness (emotional) | L | 56 | 44 | 88 |

| 12 | M | 78 | Work in noise | R | NR | 44 | 94 |

| 13 | F | 83 | Sudden deafness (ischemic) | L | 286 | 48 | 102 |

| 14 | F | 55 | ENT history (infections) | L | 603 | 29 | 85 |

| 15 | M | 79 | Sudden deafness (idiopathic) | R | 720 | 49 | 94 |

| 16 | M | 71 | Work in noise | R | NR | 42 | 69 |

| 17 | F | 65 | Sudden deafness (idiopathic) | R | 40 | 34 | 77 |

| 18 | F | 54 | Sudden deafness (emotional) | L | 91 | 52 | 79 |

| Mean | 70.7 | 193.5 | 43.4 | 85.9 | |||

| (SD) | (8.2) | (212.4) | (12.5) | (11.5) | |||

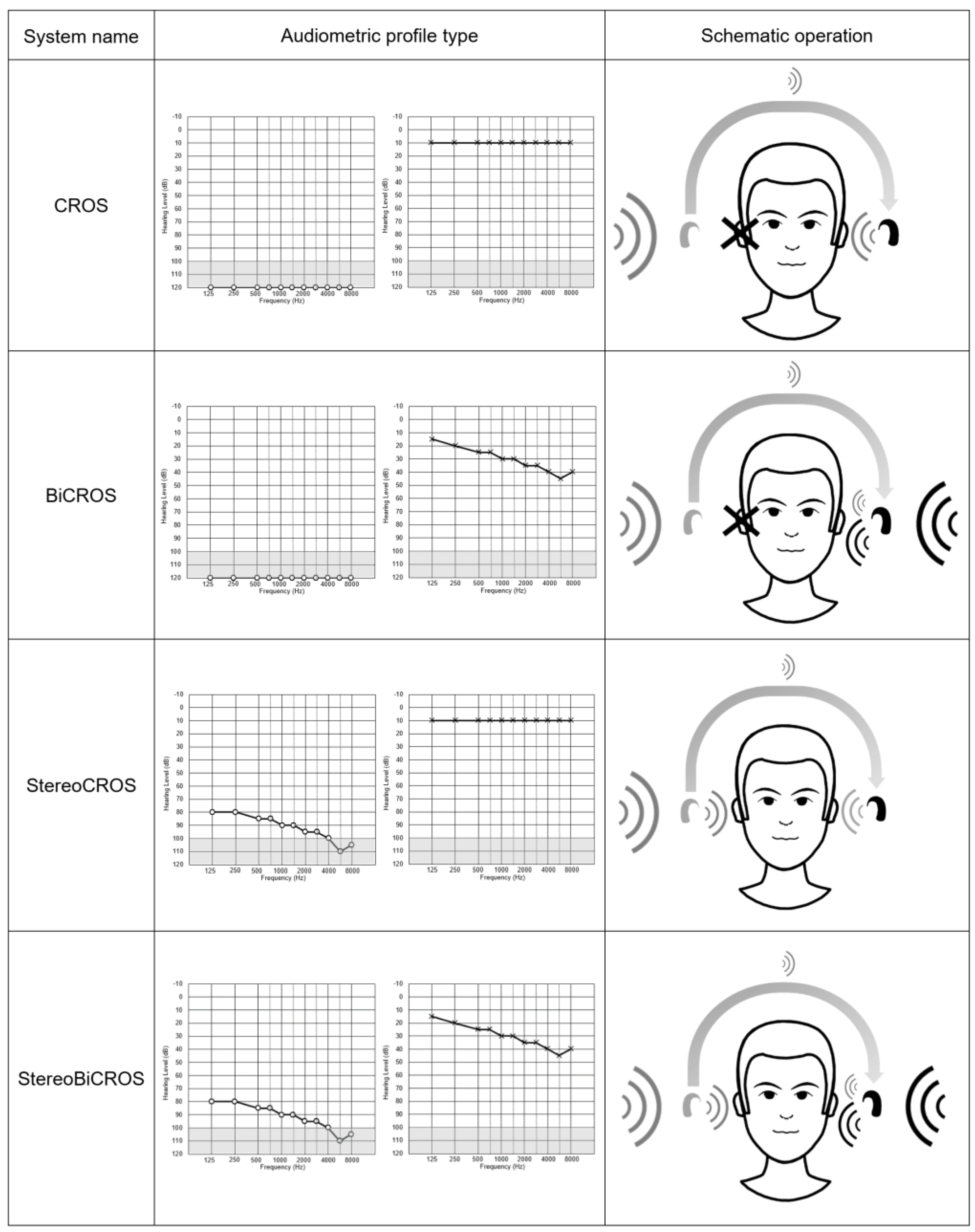

| CROS | BiCROS | Monaural HA: Poor Ear Side | Monaural HA: Better Ear Side | StereoCROS StereoBiCROS (=TriCROS) | Cochlear Implant | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description | -HA equipped with a microphone picking up sound from the deaf ear and transmits the signal to the contralateral ear, either in a wired or a wireless way. -Suitable for a non-fitting ear (SSD) and strictly for contralateral normal hearing. | -This is a CROS system to which a hearing aid is adapted to the better ear. -Suitable for a non-fitting ear (SSD) and/or mild to severe hearing loss for the other ear. | -Conventional HA (acoustic) fitting possible for residual hearing treatment. | -Conventional HA (acoustic) fitting if hearing loss to the better ear. | -Bilateral conventional HA (acoustic) fitting, possible even in case of interaural gap. | -Implantable medical device for restoring hearing to the SSD ear by electrical stimulation of the auditory nerve. |

| Advantages | -Fix the head-shadow effect. -Better at speech understanding in noise through dichotic or diotic conditions. | -In addition to the CROS system benefits, it compensates the hearing loss of the better ear. | -Restores binaurality. -Improves sound localizations. -Contributes to the treatment of tinnitus on the poor side (if associated). | -Compensates only the hearing loss. | -Restores binaurality. -Improves sound localizations. -Contributes to the treatment of tinnitus of the poor side (if associated). | -Unlike BAHA and CROS that bypass deafness by transmitting the signal to the contralateral ear, cochlear implant treats hearing loss and allows restoration of binaural mechanisms (head-shadow effect, summation effect, binaural, and Squelch effect. -Restores real binaurality. -Improves sound localization and speech discrimination in noise. |

| Disadvantages | -Does not restore binaural hearing. -Only sound capture of the deaf without any hearing restoration. -Degradation of speech discrimination in noise in reverse-dichotic condition. -Does not allow sound localization. -Does not treat tinnitus of the deaf ear, and is sometimes more detrimental. | -Identical to the CROS system. | -Only possible if sufficient residual hearing but also in the presence of a limited interaural gap allowing for stereoacoustic stimulation. -Limited results in residual capacity to the poorer ear. -Challenging fitting. | -Does not restore binaural hearing. -Definitely condemns the poor ear. | -Only possible if residual hearing sufficient but also in the presence of a limited interaural gap allowing for stereoacoustic stimulation. -Difficult fitting. | -No reimbursement from Health Insurance. -Requires surgery. -Insufficient level of clinical evidence. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Potier, M.; Noreña, A.; Seldran, F.; Marx, M.; Gallego, S. Effects of StereoBiCROS on Speech Understanding in Noise and Quality of Life for Asymmetric Sensorineural Hearing Loss. Audiol. Res. 2025, 15, 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15060176

Potier M, Noreña A, Seldran F, Marx M, Gallego S. Effects of StereoBiCROS on Speech Understanding in Noise and Quality of Life for Asymmetric Sensorineural Hearing Loss. Audiology Research. 2025; 15(6):176. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15060176

Chicago/Turabian StylePotier, Morgan, Arnaud Noreña, Fabien Seldran, Mathieu Marx, and Stéphane Gallego. 2025. "Effects of StereoBiCROS on Speech Understanding in Noise and Quality of Life for Asymmetric Sensorineural Hearing Loss" Audiology Research 15, no. 6: 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15060176

APA StylePotier, M., Noreña, A., Seldran, F., Marx, M., & Gallego, S. (2025). Effects of StereoBiCROS on Speech Understanding in Noise and Quality of Life for Asymmetric Sensorineural Hearing Loss. Audiology Research, 15(6), 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15060176