Psychiatric Comorbidities in Hyperacusis and Misophonia: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

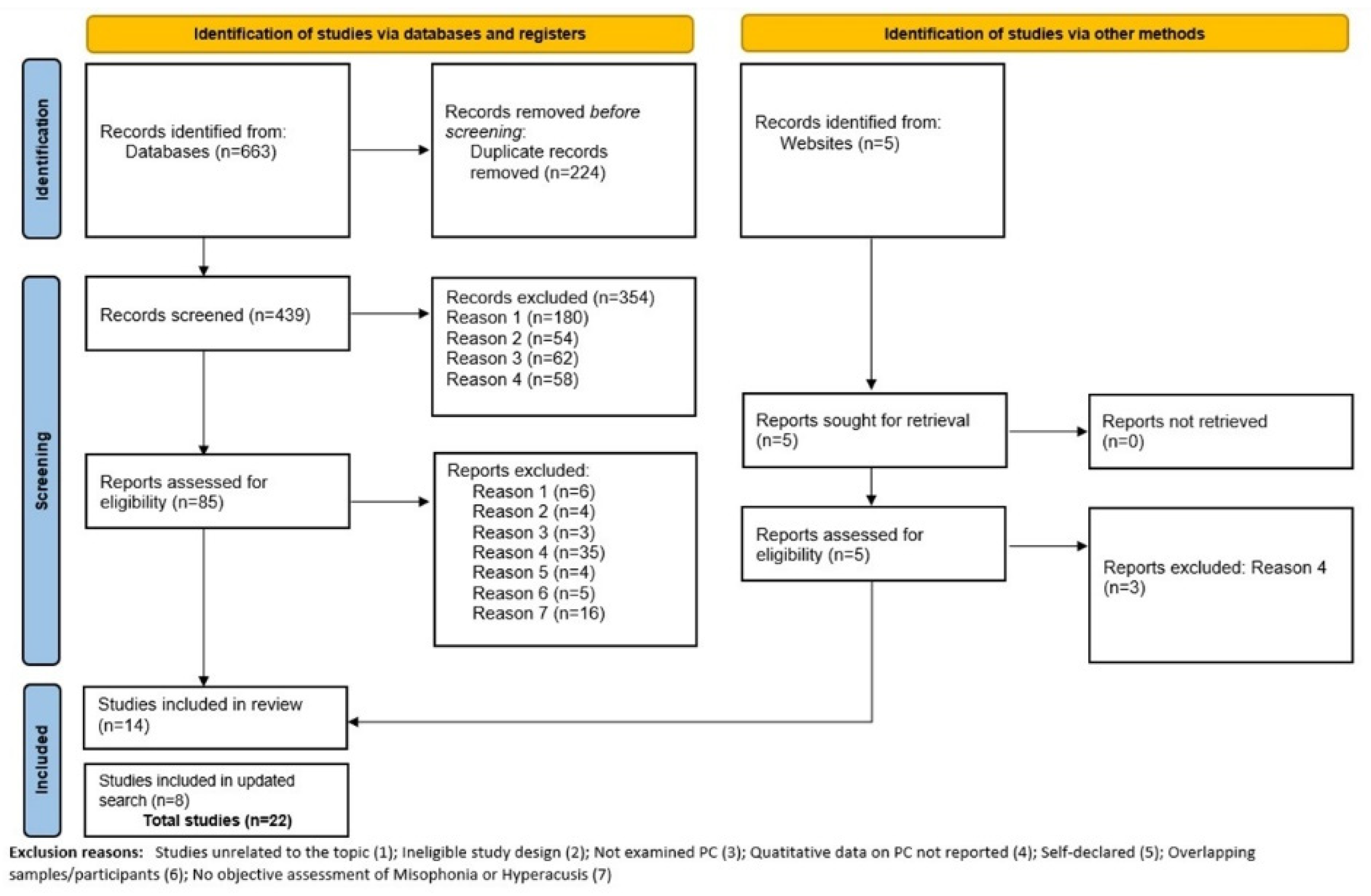

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.4. Quality and Bias Assessment

2.5. Data Synthesis and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Psychiatric Comorbidities in Hyperacusis

3.1.1. Mood Disorders

3.1.2. Anxiety Disorders

3.1.3. Other Psychiatric Disorders

3.2. Psychiatric Comorbidities in Misophonia

3.2.1. Mood Disorders

3.2.2. Anxiety and Trauma Related Disorders

3.2.3. Obsessive-Compulsive Related Disorders

3.2.4. Eating Disorders

3.2.5. Substance Use Disorders

3.2.6. Neurodevelopmental Disorders

3.2.7. Personality Disorders

3.2.8. Other Psychiatric Disorders

4. Discussion

4.1. Future Directions

4.2. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

| JBI for Prevalence Data | ||||||||||

| Author and Year | Appropriate Sample Frame | Appropriate Sampling of Participants | Adequate Sample Size | Detailed Description of Subjects and the Setting | Data Analysis: Sufficient Coverage of the Identified Sample | Valid Methods for Identification of the Condition | Standard and Reliable Measure of the Condition for All Participants | Appropriate Statistical Analysis | Adequate Response Rate or the Appropriate Management of Low Response Rate | Total Score |

| Aazh and Moore (2017) | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 5/9 |

| Begenen et al. (2023) | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 6/9 |

| Cassiello-Robbins et al. (2020) | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 5/9 |

| Erfanian et al. (2019) | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 6/9 |

| Goebel and Floetzinger (2008) | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7/9 |

| Guetta et al. (2024) | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7/9 |

| Guzick et al. (2023) | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7/9 |

| Lewin et.al (2023) | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 6/9 |

| Jager et al. (2020) | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | 6/9 |

| Jüris et al. (2012) | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 6/9 |

| Rosenthal at al. (2022) | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 6/9 |

| Schröder et al. (2013) | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 5/9 |

| Siepsiak et al. (2022) | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7/9 |

| Smit et al. (2021) | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8/9 |

| Theodoroff et al. (2024) | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7/9 |

| Yektatalab et al. (2022) | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 6/9 |

| JBI for Case Control Studies | |||||||||||

| Author and Year | Comparable Groups | Case and Controls Matched Properly | Same Criteria Used for Identification | Exposure Measured in a Standard, Valid and Reliable Way | Exposure Measured in the Same Way for Cases and Controls | Confounding Factors Identified | Strategies to Deal with Confounding Factors Stated | Outcomes Assessed in a Standard, Valid and Reliable Way for Cases and Controls | Appropriate Exposure Period | Appropriate Statistical Analysis | Total |

| Abramovitch et al. (2024) | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 6/10 |

| Rinaldi et al. (2022) 1 | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 5/10 |

| Rinaldi et al. (2022) 2 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 8/10 |

| Siepsiak et al. (2023) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 8/10 |

| 1 Population: adults with misophonia. 2 Population: Children with misophonia. | |||||||||||

| JBI for RCT | ||||||||||||||

| Author and Year | Was True Randomization Used for Assignment of Participants to Treatment Groups? | Was Allocation Concealed? | Were Treatment Groups Similar at the Baseline? | Were Participants Blind to Treatment? | Were Those Delivering Treatment Blind to Treatment Assignment? | Were Outcomes Assessors Blind to Treatment Assignment? | Were Treatment Groups Treated Identically Other Than the Intervention of Interest? | Was Follow up Complete? | Were Participants Analyzed in the Groups to Which They Were Randomized? | Were Outcomes Measured in the Same Way for Treatment Groups? | Were Outcomes Measured in a Reliable Way? | Was Appropriate Statistical Analysis Used? | Was the Trial Design Appropriate, and Any Deviations from the Standard RCT Design Accounted for in? | Total |

| Frank and McKay (2019) | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 8/13 |

| Neacsiu et al.(2024) | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 10/13 |

| Schröder et al. (2017) | N | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 7/13 |

References

- Aazh, H. Hyperacusis and Misophonia. In Tinnitus: Advances in Prevention, Assessment, and Management; Plural Publishing, Inc.: San Diego, CA, USA, 2022; pp. 287–310. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, R.; Pienkowski, M.; Roncancio, E.; Jin Jun, H.; Brozoski, T.; Dauman, N.; Anderson, G.; Keiner, A.; Cacace, A.; Martin, N.; et al. A Review of hiperacusis and future directions: Part I. Definitions and manifestations. Am. J. Audiol. 2014, 23, 402–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedo, S.E.; Baguley, D.M.; Denys, D.; Dixon, L.J.; Erfanian, M.; Fiorett, A.; Jastreboff, P.J.; Kumar, S.; Rosenthal, M.Z.; Rouw, R.; et al. Consensus Definition of Misophonia: A Delphi Study. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 841816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, R.S.; Conrad-Armes, D. The determination of tinnitus loudness considering the effects of recruitment. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 1983, 26, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jüris, L.; Andersson, G.; Larsen, H.; Ekselius, L. Psychiatric comorbidity and personality traits in patients with hyperacusis. Int. J. Audiol. 2013, 52, 230–235. [Google Scholar]

- Attri, D.N.; Nagarkar, A.N. Resolution of hyperacusis associated with depression, following lithium administration and directive counselling. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2010, 124, 919–921. [Google Scholar]

- Aazh, H.; Moore, B.C.J. Prevalence and characteristics of patients with severe hyperacusis among patients seen in a tinnitus and hyperacusis clinic. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2018, 29, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danesh, A.A.; Kaf, W. Putting Research into Practice for Autism Spectrum Disorder. Hear. J. 2015, 68, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Cassiello-Robbins, C.; Anand, D.; McMahon, K.; Brout, J.; Kelley, L.; Rosenthal, Z. A Preliminary Investigation of the Association between Misophonia and Symptoms of Psychopathology and Personality Disorders. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 847. [Google Scholar]

- Rouw, R.; Erfanian, M. A Large-Scale Study of Misophonia. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 74, 453–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.; McKenzie, J.; Bossuyt, P.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.; Mulrow, C.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaf, J.; Akl, E.; Brennan, S.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar]

- Munn, Z.; Moola, S.; Lisy, K.; Riitano, D.; Tufanaru, C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. JBI Evid. Implement. 2015, 13, 147–153. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, B.; McKay, D. The Suitability of an Inhibitory Learning Approach in Exposure When Habituation Fails: A Clinical Application to Misophonia. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2019, 26, 130–142. [Google Scholar]

- Neacsiu, A.; Beynel, L.; Gerlus, N.; LaBar, K.; Bukhari-Parlakturk, N.; Rosenthal, Z. An experimental examination of neurostimulation and cognitive restructuring as potential components for Misophonia interventions. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 350, 274–285. [Google Scholar]

- Schröder, A.; Vulink, N.; van Loon, A.; Denys, D. Cognitive behavioral therapy is effective in misophonia: An open trial. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 217, 289–294. [Google Scholar]

- Abramovitch, A.; Herrera, T.; Etherton, J. A neuropsychological study of misophonia. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2024, 82, 101897. [Google Scholar]

- Begenen, A.; Aydin, F.; Demirci, H.; Ozer, O. A comparison of clinical features and executive functions between patients with obsessive compulsive disorder with and without misophonia. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2023, 36, 90–102. [Google Scholar]

- Erfanian, M.; Kartsonaki, C.; Keshavarz, A. Misophonia and comorbid psychiatric symptoms: A preliminary study of clinical findings. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2019, 73, 230–235. [Google Scholar]

- Goebel, G.; Floetzinger, U. Pilot study to evaluate psychiatric co-morbidity in tinnitus patients with and without hyperacusis. Audiol. Med. 2008, 6, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guetta, R.; Siepsiak, M.; Shan, Y.; Frazer-Abel, E.; Rosenthal, M. Misophonia is related to stress but not directly with traumatic stress. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0296218. [Google Scholar]

- Guzick, A.; Cervin, M.; Smith, E.; Clinger, J.; Draper, I.; Goodman, W.; Lijffijt, M.; Murphy, N.; Lewin, A.; Schneider, S.; et al. Clinical characteristics, impairment, and psychiatric morbidity in 102 youth with misophonia. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 324, 395–402. [Google Scholar]

- Jager, I.; Koning, P.; Bost, T.; Denys, D.; Vulink, N. Misophonia: Phenomenology, comorbidity and demographics in a large sample. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231390. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, A.; Milgram, L.; Cepeda, S.; Dickinson, S.; Bolen, M.; Kudryk, K.; Bolton, C.; Karlovich, A.; Grassie, H.; Kangavary, A.; et al. Clinical characteristics of treatment-seeking youth with misophonia. J. Clin. Psychol. 2024, 80, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, M.Z.; McMahon, K.; Greenleaf, A.S.; Cassiello-Robbins, C.; Guetta, R.; Trumbull, J.; Anand, D.; Frazer-Abel, E.; Kelley, L. Phenotyping misophonia: Psychiatric disorders and medical health correlates. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 941898. [Google Scholar]

- Schröder, A.; Vulink, N.; Denys, D. Misophonia: Diagnostic Criteria for a New Psychiatric Disorder. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54706. [Google Scholar]

- Siepsiak, M.; Rosenthal, M.Z.; Raj-Koziak, D.; Dragan, W. Psychiatric and audiologic features of misophonia: Use of a clinical control group with auditory over-responsivity. J. Psychosom. Res. 2022, 156, 110777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siepsiak, M.; Turek, A.; Michałowska, M.; Gambin, M.; Dragan, W. Misophonia in Children and Adolescents: Age Diferences, Risk Factors, Psychiatric and Psychological Correlates. A Pilot Study with Mothers’ Involvement. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2023, 56, 758–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoroff, S.; Reavis, K.; Norrholm, S. Prevalence of Hyperacusis Diagnosis in Veterans Who Use VA Healthcare. Ear Hear. 2024, 45, 499–504. [Google Scholar]

- Aazh, H.; Moore, B. Usefulness of self-report questionnaires for psychological assessment of patients with tinnitus and hyperacusis and patients’ views of the questionnaires. Int. J. Audiol. 2017, 56, 489–498. [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi, L.J.; Simner, J.; Koursarou, S.; Ward, J. Autistic traits, emotion regulation, and sensory sensitivities in children and adults with Misophonia. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2022, 53, 1162–1174. [Google Scholar]

- Smit, A.L.; Stegeman, I.; Eikelboom, R.H.; Baguley, D.; Bennett, R.J.; Tegg-Quinn, S.; Bucks, R.; Stokroos, R.J.; Hunter, M.; Atlas, M.D. Prevalence of Hyperacusis and Its Relation to Health: The Busselton Healthy Ageing Study. Laryngoscope 2021, 131, E2887–E2896. [Google Scholar]

- Yektatalab, S.; Mohammadi, A.; Zarshenas, L. The Prevalence of Misophonia and Its Relationship with Obsessive-compulsive Disorder, Anxiety, and Depression in Undergraduate Students of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Community Based Nurs. Midwifery 2022, 10, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. World Health Organization Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/depression-global-health-estimates (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Santomauro, D.F.; Herrera, A.M.M.; Shadid, J.; Zheng, P.; Ashbaugh, C.; Pigott, D.M.; Abbafati, C.; Adolph, C.; Amlag, J.O.; Aravkin, A.Y.; et al. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2021, 398, 1700–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aazh, H.; Najjari, A.; Moore, B.C.J. A Preliminary Analysis of the Clinical Effectiveness of Audiologist-Delivered Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Delivered via Video Calls for Rehabilitation of Misophonia, Hyperacusis, and Tinnitus. Am. J. Audiol. 2024, 32, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Country | Study Design | Study Setting | Aim(s) | Initial Sample Size a) | Hyperacusis Sample Size | Comorbid Tinnitus | Hyperacusis Diagnosis | Hyperacusis Sample Age (Mean, SD) | Gender: Female (n, %) | Exclusion Criteria | Psychiatric Diagnostic Method(s) b) | Psychopathology Quantitative Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aazh and Moore (2017) | United Kingdom | Observational cross-sectional questionnaire-based study | clinical-referral sample | To determine the relevance and applicability of psychological questionnaires to patients seeking help for tinnitus and/or hyperacusis | 145 | 37 | Not reported | Hyperacusis questionnaire (HQ) score 26 | Not specified for the hyperacusis sample | Not specified for the hyperacusis sample | Not specified | HADS (depression and anxiety); GAD-7 (anxiety); SHAI (Health anxiety); Mini-SPIN (social anxiety); OCI-R (OCD); PDSS-SR (panic disorder); PHQ-9 (depression); PSWQ-A (GAD) | Mood disorders—depression: 47% Anxiety disorders—anxiety: 61%; health anxiety: 56%; GAD: 53%; social anxiety: 51%; OCD: 37%; panic disorder: 37% |

| Goebel and Floetzinger (2008) | Germany | Cross-sectional observational pilot study | Clinical inpatient sample | To investigate the type and degree of psychiatric comorbidity in patients with chronic tinnitus with and without hyperacusis | 163 | 95 | 100% | Structured Tinnitus Interview (STI) items; STI Hyperacusis scale | Not specified for the hyperacusis sample | Not specified for the hyperacusis sample | More than moderate hearing loss (better ear), severe recruitment, conflicts with insurances or desire to gain retired status; substance abuse, Meniere’s disease, middle ear muscle dysfunction, Williams syndrome, Ramsay-Hunt syndrome, facial paralysis, episodes of hypoglycaemia, hyperthyreosis, phaeo-chromocytom, carcinoids, epilepsy; psychotic or schizoaffective disorders and certain mental disorders | Checklists for ICD-10; BDI (depression); BAI (anxiety); WI (health anxiety) | Depression: 58% anxiety disorder: 39%; somatoform disorder: 22% |

| Jüris et al. (2012) | Sweden | Not specified | Clinical outpatient sample | To investigate psychiatric comorbidity based on DSM-IV and personality traits in patients with hyperacusis | 81 | 62 | 79% | Uncomfortable loudness levels (ULLs); hearing levels | 40.2 (12.2) | 47 (76%) | Tinnitus as the primary audiological problem; Hearing levels < 40 dB | MINI for DSM-IV and ICD-10 | Mood Disorders— any affective disorder: 15%; MDD: 8% dysthymic disorder: 8% Anxiety Disorders—any anxiety disorder: 47%; social phobia: 23%; GAD: 16%; agoraphobia: 15%; OCD: 10%; panic disorder: 6%; PTSD: 3% Other disorders— any alcohol abuse: 5%; eating disorders: 2% |

| Smit et al. (2021) | Australia | Prospective population-based study | Non-clinical community sample | To determine the prevalence of hyperacusis and its relation with hearing, general and mental health in a population-based study | 5107 | 775 | 40.5% | Single screening question: “Do you consider yourself sensitive or intolerant to everyday sounds” | 58.83 (5.82) | 452 (58.3%) | Institutionalized adults | PHQ-9 (used against DSM-IV criteria and following severity cut-off scores) DASS-21 | DASS-21—Depression (overall severity): 41%; anxiety (overall severity): 43% PHQ-9—Depression (overall severity): 79.9%; MMD (DSM-IV): 5.7%; other depressive disorder (DSM-IV): 4.5% |

| Theodoroff et al. (2024) | USA | Retrospective observational study | Clinical inpatient and outpatient samples | To estimate the prevalence of hyperacusis diagnosis in treatment-seeking veterans | 5,744,670 | 3724 | 73% | ICD billing codes (ICD-9 and ICD-10) | Not specified | 839 (22.5%) | Not specified | Medical records review | PTSD: 49% |

| Study | Country | Study Design | Study Setting | Aim(s) | Initial Sample Size a) | Misophonia Sample Size | Misophonia Diagnosis | Misophonia Sample Age (Mean, SD) | Gender: Female (n, %) | Exclusion Criteria | Psychiatric Diagnostic Method(s) b) | Psychopathology Quantitative Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abramovitch et al. (2024) | USA | Case-control observational study | Community sample (students) | To conduct the first neuropsychological study of misophonia in the context of cognitive function. | 275 | 32 | Misophonia Questionnaire (MQ) | 21.06 (2.45) | 19 (59.40%) | Age< 18 or > 65; any history of major neurological conditions; uncorrected vision problems; non-English speakers | MINI 7.0 for DSM-5 | Mood disorders—MDD: 3.10% Anxiety and Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders—GAD: 3.1%; social anxiety disorder: 3.1%; panic:6.3%; agoraphobia: 3.2%; OCD: 9.4%; PTSD: 3.1%; any anxiety disorder: 18.8% Eating disorders—anorexia nervosa:3.1%; Bulimia nervosa: 3.1%; binge eating: 3.1%; any eating disorder: 6.3% Other disorders—ADHD: 15.6%; substance abuse 9.4%; any current DSM disorder: 31.30% |

| Begenen et al. (2023) | Turkey | Cross-sectional observational study | Clinical-referral sample (psychiatric clinic) | To compare patients with OCD with and without misophonia in terms of sociodemographic data, clinical features, and executive functions. | 77 | 39 | AMC 2013 criteria (Schröder et al.); | 23.9 (6) | 23 (56%) | Presence of dementia, psychotic disorder, BD, SUD, suicide ideations, intellectual disability; chronic internal/neurological conditions; moderate to- severe depressive disorder and patients who could not complete neuropsychiatric tests | SCID-5 for DSM-5 | Mood disorders—depressive disorder: 17.9%; dysthymic disorder:5.1%; premenstrual dysphoric disorder:15.4% Anxiety and Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders—GAD: 12.8%; social anxiety disorder: 17.9%; panic:10.3%; agoraphobia: 25.6%; specific phobia:12.8%; any obsessive-compulsive: 35.9%; any anxiety disorder: 59%; body dysmorphic disorder: 2.6%; excoriation: 5.1%; hoarding: 12.8%; onychophagia:17.9% Neurodevelopmental disorders ADHD: 20.5%; tic disorder: 5.1%; Other disorders—hypochondria: 2.6%; binge eating: 15.4%; gambling addiction: 5.1%; any psychiatric disorder: 82.1% |

| Cassiello-Robbins et al. (2021) | USA | Cross-sectional correlational study | Community sample | To examine the relationship between symptoms of misophonia and psychiatric diagnoses in a sample of community adults, using semi-structured diagnostic interviews | NA | 49 | Misophonia Questionnaire (MQ) | 27.02 (8.75) | 42 (85.7%) | Age ≤ 18; current mania or psychotic disorder | SCID-I for DSM-IV (Axis I disorders); SCID-II for DSM-IV (Axis II—personality disorders); BDI-II (depressive symptoms); BAI (anxiety symptoms) | Mood disorders—MDD: 18.4% Anxiety and Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders—GAD: 32.7%; social anxiety disorder: 10.2%; OCD: 6.1%; PTSD: 18.4% Personality Disorders—APD: 8.2%; BPD: 12.2%; OCPD: 10.2% |

| Erfanian et al. (2019) | Iran | Cross-sectional observational study | Clinical-referral sample (psychiatric clinic) | To examine the prevalence of psychiatric symptoms in clinically diagnosed misophonia sufferers, the association between misophonia severity and psychiatric symptoms, and gender | NA | 52 | AMC 2013 criteria (Schröder et al.); Amsterdam Misophonia Scale (A-MISO-S) | 45.27 (16.23) | 30 (58%) | A-MISO-S score ≤ 4; co-morbid tinnitus, hyperacusis, diplacusis, hearing impairment; patients taking antidepressants or anxiolytics in the last 2 week | MINI 5.0.0 | Mood Disorders—MDD: 9.61%; dysthymia: 5.76%; suicidality: 1.92% Anxiety and Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders—PTSD: 15.38%; OCD: 11.53%; social phobia: 5.76%; panic: 1.92%; agoraphobia; 1.92%; GAD: 1.92% Eating Disorders—anorexia: 9.61%; bulimia: 7.69% Substance use disorders—alcohol dependence: 3.84%; alcohol abuse: 3.84%; substance dependence: 1.92%; substance abuse 1.92% Other disorders—psychotic disorders: 1.92% |

| Frank and McKay (2019) | USA | RCT (in-progress) | Community sample | To assess effect of inhibitory learning as a treatment paradigm for misophonia. | 58 | 18 | Misophonia Questionnaire (MQ) | 34.94 (10.95) | Not reported | Not Specified | SCID-5 for DSM-5; DASS-21 | Mood disorders—MDD: 22%; PDD: 11%; premenstrual dysphoric disorder: 6% Anxiety Disorders and Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders panic disorder: 6%; GAD: 17%; specific phobia: 11%; social anxiety disorder: 11%; agoraphobia: 11%; OCD: 11%; excoriation: 6% Other disorders—adult ADHD: 6%; alcohol use disorder: 11%; hypersomnolence disorder: 11% |

| Guetta et al. (2024) | USA | Cross-sectional correlational study | Community sample | To understand the relationships among misophonia, stress, and trauma in a community sample and to examine mechanisms of trauma and stress-related sequelae that contribute to misophonia severity | N/A | 143 | Self-reported. | 36.88 (18.84) | 100 (69.9%) | Current psychotic disorder, mania, and anorexia nervosa | SCID-5 for DSM-5, research version; PCL-5 for DSM-5 | Trauma and stressor-related disorder—PTSD: 3.5%; adjustment disorder 2.8%; trauma disorder OS: 5.6%; |

| Guzick et al. (2023) | USA | Cross-sectional observational study | Community sample | To describe the clinical phenomenology of youth with misophonia and to evaluate associations between misophonia severity and psychiatric symptoms, as well as quality of life | 152 | 102 | Amsterdam Misophonia Scale (A-MISO-S) | 13.7 (2.5) | 69 (68%) | A-MISO-S score ≤ 10; unable to schedule appointments | MINI-KID | Mood disorders—MDE: 15% Anxiety and Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders—GAD: 27% social anxiety disorder: 30% OCD: 8% Neurodevelopmental disorders ADHD: 21%; tic disorder 13% At least one anxiety disorder: 56% |

| Jager et al. (2020) | Netherlands | Cross-sectional observational study | Clinical-referral sample (outpatient psychiatric university clinic) | To determine whether GP referred subjects with misophonia-like symptoms actually suffered from misophonia using a psychiatric interview, and to determine phenomenology, comorbidity, and demographics of a large misophonia sample | 779 | 575 | AMC 2013 criteria (Schröder et al.); Amsterdam Misophonia Scale (A-MISO-S); Amsterdam Misophonia Scale—Revised (A-MISO-R) | 34.17 (12.22) | 399 (69%) | Primary autism spectrum conditions; primary AD(H)D; a primary diagnosis on Axis II; subjects without a DSM-IV diagnosis | MINI-Plus; SCID-II for DSM-IV (Axis II—personality disorders); HAM-D; HAM-A; Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ) | Mood disorders—MDD: 6.8%; dysthymic disorder: 1.7%; BD II: 0.7%; BD I: 0.5%; depressive disorder NOS: 0.3% Anxiety and Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders—OCD: 2.8%; PTSD: 1.7%; social phobia: 1.2%; GAD: 1.0%; specific phobia: 1.0%; panic disorder with agoraphobia: 0.9%; separation anxiety disorder: 0.2%; anxiety disorder NOS: 0.2%; trichotillomania or excoriation disorder: 1.9% Neurodevelopmental disorders -autistic disorder: 1.2%; pervasive developmental disorder NOS: 1.2%; attention deficit disorder: 3.3%; ADHD: 1.7%; ADHD combined type: 0.3%; tic disorder NOS: 0.5%; chronic motor or vocal tic disorder: 0.5%; Tourette syndrome: 0.3%; tic disorder: 0.2%; stuttering: 0.2% Substance use disorders—alcohol dependence: 0.7%; cannabis or dependence on sedatives: 0.5%; abuse of alcohol: 0.3% Personality disorders—OCPD: 2.4% BPD: 1.7%; avoidant PD: 0.5%; dependent PD: 0.2%; antisocial PD: 0.2% Other disorders—eating disorder NOS: 0.7%; intermittent explosive disorder: 0.2%; hypochondria: 0.9%; undifferentiated somatoform disorder: 0.5%; schizophrenia: 0.2% |

| Lewin et.al (2023) | USA | Cross-sectional observational study | Community Sample | To examine the clinical characteristics of youth with misophonia. | 47 | 46 | Misophonia assessment interview (MAI; Lewin, 2020; | 13.2 (2) | 32 (69.6%) | Past treatment for emotional disorders or misophonia; Active psychotic disorder, BD, eating disorder, alcohol/SUD, intellectual disability, or suicidal ideation | ADIS-5 | Mood Disorders—MDD: 8.5%; dysthymia:4.3% Anxiety and Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders—OCD: 2.1%; PTSD: 6.4%; GAD: 36.2%; specific phobia: 12.9%; separation anxiety disorder: 2.1%; Social anxiety: 29.8%; any anxiety disorder: 59.6% Neurodevelopmental disorders—autistic disorder: 4.3%; ADHD: 14.9%; tic disorder: 6.4%; Other: oppositional defiant disorder:8.5% |

| Neacsiu et al. (2024) | USA | Intervention Study | Community Sample | To test differences between adults with misophonia and clinical controls on HF-HRV, SCL, SCR, and self-reported distress during passive listening and regulation of aversive and misophonic sounds. to examine whether misophonia interventions should target reduction of sound reactivity or improvement in emotion regulation. | 1341 | 29 | Misophonia Questionnaire (MQ) | 29.59 (9.79) | 26 (89.66%) | Current or past history of mania or psychosis; IQ < 70; not medically cleared for TMS or fMRI; going to jail in the next 2 months; pregnant; high risk of suicide; moderate/severe current alcohol or substance dependence; unable to attend for 3 visits | SCID-5, SCID-PD | Mood disorders: 13.8% Anxiety disorders: 69% Obsessive compulsive disorders: 6.9% Stress disorders: 10.3% Impulse control disorders: 6.9% Eating disorders: 3.4% |

| Rinaldi et al. (2022) | United Kingdom | Case-control observational study | Community sample | To investigate what traits might contribute to the profile of people with misophonia, particularly traits typically associated with autism | 379 | 126 | Sussex Misophonia Scale (SMS) | 30.32 (17.21) | 92 (73%) | Self-declared misophonics who did not pass the diagnostic threshold | Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ) | Autism clinical significant threshold: 21.4% |

| To examine whether adolescents with misophonia already show autism-related traits, similar to adults | 142 | 15 (12 with valid AQ) | Sussex Misophonia Scale for Adolescents (SMS-As) | Girls: 11.67 (1.32); Boys: 11 (0.89) | 9 (60%) | Not specified | Autism Spectrum Quotient for Adolescents (AQ-Adolescents) | Autism clinical significant threshold: 12.5% | ||||

| Rosenthal et al. (2022) | USA | Cross-sectional correlational study | Community sample | To improve the phenotypic characterization of misophonia by investigating its psychiatric and medical health correlates in adults | 210 | 207 | Misophonia Questionnaire (MQ) | 35.72 (12.49) | 154 (74.4%) | MINI 7.0.2. criteria for a current psychotic disorder, mania, anorexia; inability to read English | SCID-5 for DSM-5, research version; SCID-5-PD for DSM-5 personality disorders | Mood Disorders—MDD: 6.8%; BD I: 0.5%; BD II: 0.5%; PDD: 7.7%; premenstrual dysphoric disorder: 1.9%; depressive disorder OS: 1.4% Anxiety and Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders—GAD: 24.6%; panic: 2.9%; social anxiety: 30.9%; agoraphobia: 10.1%; specified phobia: 13.5%; OCD: 8.2%; PTSD: 2.9%; body dysmorphic disorder: 0.5%; excoriation: 5.3%; hoarding: 1.9%; trichotillomania: 1.9% Substance use disorders—alcohol: 1.9%; cannabis: 1.4%; stimulants/cocaine: 0.5%; other SUD: 0.5% Eating disorders—bulimia nervosa: 1.4%; binge eating: 0.5%; eating disorder OS: 2.9% Neurodevelopmental disorders ADHD: 17.9%; adult ADHD: 14.5%; ASD: 2.4%; tic disorder: 1.9%; stuttering: 0.5%; specific learning disorder: 0.5%; speech sound disorder: 3.9% Personality disorders—OCPD: 5.8%; avoidant PD: 2.9%; BPD: 2.9%; dependent PD: 0.5%; narcissistic PD: 0.5%; paranoid PD: 0.5% |

| Schröder et al. (2013) | Netherlands | Cross-sectional observational study | Community sample (recruited via hospital website) | To describe the clinical symptomatology of misophonia, discuss the classification of symptoms, propose diagnostic criteria, and introduce A-MISO-S | NA | 42 | Amsterdam Misophonia Scale (A-MISO-S) | Not reported (adult sample) | 20 (47.6%) | Not specified | SCID-II for DSM-IV (Axis II) —personality disorders); HAM-D (depression level); HAM-A (anxiety symptoms) | Mood Disorder—dysthymic disorder: 7.1% Anxiety and Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders—OCD: 2.4; panic disorder: 2.4%; excoriation: 2.4%; trichotillomania: 4.8% Neurodevelopmental disorders—ADHD: 4.8%; Tourette syndrome: 4.8% Personality disorders—OCPD: 52.4% Other disorders—hypochondria: 2.4% |

| Schröder et al. (2017) | Netherlands | Intervention study (open-label trial) | Clinical-referral sample | To determine the efficacy of CBT and to investigate if clinical or demographic characteristics predicted treatment response | NA | 90 | Psychiatrist screening | 35.8 (12.2) | 65 (72%) | Presence of substance dependence, BD, ASD, or psychotic disorders | Psychiatrist screening | Mood Disorders—MDD: 1.1%; dysthymic disorder: 2.2%; BD II: 1.1% Anxiety and Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders—OCD: 3.3%; excoriation: 5.5%; body dysmorphic disorder: 1.1% Neurodevelopmental disorders— ADHD: 4.4%; Tourette syndrome: 2.2% Other disorders—bulimia/anorexia: 3.3%; hypochondria: 1.1% |

| Siepsiak et al. (2022) | Poland | Cross-sectional observational study | Community sample (students) | To examine the psychiatric and audiologic features of misophonia, by comparing three groups (a misophonia group, an audiologically healthy control group and a clinical control group) | 156 | 71 | AMC 2013 criteria (Schröder et al.); MisoQuest | 31.04 (8.79) | 64 (90.1%) | Participants with heart diseases, pacemakers, facial hair, or a current substance use disorder | MINI 7.0.2 for DSM-5 and ICD-10 | Mood Disorders—MDE: 37.3%; MDD: 11.9%; BD I: 9.0%; BD I with psychotic features: 4.5%; BD II: 1.5%; suicidality: 20.0%; suicidal behavior: 3.0% Anxiety disorders—panic disorder: 19.4%; GAD: 14.9%; social anxiety disorder: 13.4%; PTSD: 11.9%; OCD: 6.0%; agoraphobia: 4.5%; Eating Disorders—anorexia: 1.5%; Bulimia: 1.5% |

| Siepsiak et al. (2023) | Poland | Case-control observational study | Community sample | To evaluate preliminary findings from previous research on misophonia within a Polish sample of children and adolescents and develop new hypotheses to test in further studies. | N/A | 45 | Amsterdam Misophonia Scale (A-MISO-S) | 13.1 (3) | 68.2% | Diagnosis of ASD, intellectual disability, serious somatic illness, hearing loss, and serious sight impairment | Neurodevelopmental disorders—ADHD: 2.4%; ADHD combined type: 7.1%; ADD:16.7%; tic disorder: 18.2%; Other: OCD: 13.6% | |

| Yektatalab et al. (2022) | Iran | Cross-sectional descriptive observational study | Community sample | To determine the prevalence of misophonia and its relationship with obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety, and depression in undergraduate students | 390 | 93 | Misophonia Questionnaire (MQ) | Not reported (undergraduate sample) | Not specified for the misophonia sample | Self-reported hearing diseases | Maudsley Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory; BAI (2nd Ed); BDI (2nd Ed) | Mood Disorders—depression: 9.7% Anxiety and Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders—OCD: 39.8%; anxiety: 8.6% |

| Mood Disorders | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | Dysthymic Disorder | Any Affective Disorder | |

| Aazh and Moore (2017) b (N = 37) | 47% * | - | - |

| Goebel and Floetzinger (2008) a (N = 95) | 64% | - | - |

| Jüris et al. (2012) a (N = 62) | 8% | 8% | 15% |

| Smit et al. (2021) b (N = 775) | 80% * 41% ** | - | - |

| Anxiety Disorders | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety Disorder | Generalized Anxiety Disorder | Panic Disorder | Social Anxiety Disorder | Agoraphobia Disorder | OCD | PTSD | |

| Aazh and Moore (2017) b (N = 37) | 61% | 53% | 37% | 51% | - | 37% | - |

| Goebel and Floetzinger (2008) a (N = 95) | 39% | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Juris et al. (2012) a (N = 62) | 47% | 16% | 6% | 23% | 15% | 10% | 3% |

| Smit et al. (2021) b (N = 775) | 42.9% | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Theodoroff et al. (2024) a (N = 3724) | - | - | - | - | - | - | 49% |

| Mood Disorders | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression Symptomology | Major Depressive Disorder | Major Depressive Episode | Persistent Depressive Disorder | Dysthymic Disorder | Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder | Suicide Behavior Disorder | Bipolar Disorder | Any Mood Disorder | |

| Abramovitch et al. (2024) a (N = 32) | - | 3.1% | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Begenen et al. (2023) a (N = 39) | - | 17.9% | - | - | 5.1% | 15.4% | - | - | - |

| Cassiello-Robbins et al. (2021) a (N = 49) | - | 18.4% | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Erfanian et al. (2019) a (N = 52) | - | 9.61% | - | - | 5.76% | - | 1.92% | - | - |

| Frank and McKay. (2019) a (N = 18) | - | 11% | - | - | - | 6% | - | - | - |

| Guzick et al. (2023) a (N = 102) | - | - | 15% | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Jager et al. (2020) a (N = 575) | - | 6.8% | - | - | 1.7% | - | - | 1.2% | - |

| Lewin et.al (2023) a (N = 46) | - | - | 8.5% | - | 4.3% | - | - | - | - |

| Neacsiu et al. (2024) a (N = 29) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 13.8% |

| Rosenthal et al. (2022) a (N = 207) | - | 6.8% | - | 7.7% | - | 1.9% | - | 1.0% | - |

| Schröder et al. (2013) a (N = 42) | - | 7.1% | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Schröder et al. (2017) a (N = 90) | - | 1.1% | - | - | 2.2% | - | - | 1.1% | - |

| Siepsiak et al. (2022) a (N = 71) | - | 11.9% | 37.3% | - | - | - | 20% | 10.5% (w/psychotic features 4.5%) | - |

| Yektatalab et al. (2022) b (N = 93) | 9.7% | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Anxiety and Trauma Related Disorders | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Anxiety Disorder | GAD | Social Anxiety | Panic | Agoraphobia | Separation Anxiety Disorder | Specified Phobia | PTSD | Adjustment Disorder | Any Trauma/Stress Disorder | |

| Abramovitch et al. (2024) a (N = 32) | 18.8% | 3.1% | 3.1% | 6.3% | 3.2% | - | - | 3.1% | - | - |

| Begenen et al. (2023) a (N = 39) | 59% | 12.8% | 17.9% | 10.3% | 25.6% | - | 12.8% | - | - | - |

| Cassiello-Robbins et al. (2021) a (N = 49) | - | 32.7% | 10.2% | - | - | - | - | 18.4% | - | - |

| Erfanian et al. (2019) a (N = 52) | - | 1.9% | 5.7% | 1.9% | 1.9% | - | - | 15.4% | - | - |

| Frank and McKay. (2019) a (N = 18) | - | 17% | 11% | 6% | 11% | - | - | - | - | - |

| Guetta et al. (2024) a | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3.5% | 2.8% | 5.5% |

| Guzick et al. (2023) a (N = 102) | - | 27% | 30% | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Jager et al. (2020)a (N = 575) | 0.2% | 1.0% | 1.2% | 0.9% | - | 0.2% | - | 1.7% | - | - |

| Lewin et.al (2023) a (N = 46) | 59.6% | 36.2% | 29.8% | - | - | 2.1% | 12.9% | 6.4% | - | - |

| Neacsiu et al. (2024) a (N = 29) | 69% | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 10.3% |

| Rosenthal et al. (2022) a (N = 207) | - | 24.6% | 30.9% | 2.9% | 10.1% | - | 13.5% | 2.9% | - | - |

| Schröder et al. (2013) a (N = 42) | - | - | - | 2.4% | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Siepsiak et al. (2022) a (N = 71) | - | 14.9% | 13.4% | 19.4% | 4.5% | - | - | 11.9% | - | - |

| Yektatalab et al. (2022) b (N = 93) | 8.6% | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Obsessive-Compulsive Related Disorders | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCD | Body Dysmorphia | Excoriation | Hoarding | Trichotillomania | Onychophagia | |

| Abramovitch et al. (2024) a (N = 32) | 9.4% | - | - | - | - | - |

| Begenen et al. (2023) a (N = 39) | - | 2.6% | 5.1% | 12.8% | - | 17.9% |

| Cassiello-Robbins et al. (2021) a (N = 49) | 6.1% | - | - | - | - | - |

| Erfanian et al. (2019) a (N = 52) | 11.5% | - | - | - | - | - |

| Frank and McKay. (2019) a (N = 18) | - | - | 6% | - | - | - |

| Guzick et al. (2023) a (N = 102) | 8% | - | - | - | - | - |

| Jager et al. (2020)a (N = 575) | 2.8% | - | - | - | 1.9% | - |

| Lewin et.al (2023) a (N = 46) | 2.1% | - | - | - | - | - |

| Rosenthal et al. (2022) a (N = 207) | 8.2% | - | 5.3% | 1.9% | 1.9% | - |

| Schröder et al. (2013) a (N = 42) | 2.4% | - | 2.4% | - | 4.8% | - |

| Schröder et al. (2017) a (N = 90) | 3.3% | 1.1% | 5.5% | - | - | - |

| Siepsiak et al. (2022) a (N = 71) | 6% | - | - | - | - | - |

| Yektatalab et al. (2022) b (N = 93) | 39.8% | - | - | - | - | - |

| Eating Disorders | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Eating Disorder | Anorexia | Bulimia | Binge Eating | Other | |

| Abramovitch et al. (2024) a (N = 32) | 6.3% | 3.1% | 3.1% | 3.1% | - |

| Begenen et al. (2023) a (N = 39) | - | - | - | 15.4% | - |

| Erfanian et al. (2019) a (N = 52) | - | 9.6% | 7.7% | - | - |

| Jager et al. (2020) a (N = 575) | 0.7% | - | - | - | - |

| Neacsiu et al. (2024) a (N = 29) | 3.4% | - | - | - | - |

| Rosenthal et al. (2022) a (N = 207) | - | - | 1.4% | 0.5% | 0.5% |

| Siepsiak et al. (2022) a (N = 71) | - | 14.9% | 11.9% | - | - |

| Substance Use Disorders | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substance Dependence | Alcohol Dependence | Cannabis Dependence | Cocaine Dependence | Other | |

| Abramovitch et al. (2024) (N = 32) | 9.4% | - | - | - | - |

| Erfanian et al. (2019) a (N = 52) | 1.92% | 3.84% | - | - | - |

| Frank and McKay. (2019) a (N = 18) | - | 11% | - | - | - |

| Jager et al. (2020) a (N = 575) | - | 1.0% | 0.5% | - | - |

| Rosenthal et al. (2022) a (N = 207) | - | 1.9% | 1.4% | 0.5% | 0.5% |

| Neurodevelopmental Disorders | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attention Deficit Disorder | Autism Spectrum Disorder | Tic Disorder | ||||||

| ADHD | ADD | Combined | Autistic Disorder | Pervasive Development Disorder | Tic disorder | Gilles de la Tourette | Chronic Motor Disorder | |

| Abramovitch et al. (2024) a (N = 32) | 15.6% | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Begenen et al. (2023) a (N = 39) | 20.5% | - | - | - | - | 5.1% | - | - |

| Frank and McKay. (2019) a (N = 18) | 6% | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Guzick et al. (2023) a (N = 102) | 21% | - | - | - | - | 13% | - | -- |

| Jager et al. (2020) a (N = 575) | 1.7% | 3.3% | 0.3% | 1.2% | 1.2% | 0.3% | 0.5% | |

| Lewin et.al (2023) a (N = 46) | 14.9% | - | - | 4.3% | - | 6.4% | - | - |

| Rinaldi et al. (2022) b (N = 126) | - | - | - | 21.4% * | - | - | - | - |

| Rinaldi et al. (2022) b (N = 15) | - | - | - | 12.5% ** | - | - | - | - |

| Rosenthal et al. (2022) a (N = 207) | 17.9% | - | - | 2.4% | - | - | - | -- |

| Schröder et al. (2013) a (N = 42) | 4.8% | - | - | - | - | - | 4.8% | - |

| Schröder et al. (2017) a (N = 90) | 4.4% | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Siepsiak et al. (2023) a (N = 45) | 2.4% | 16.7% | 7.1% | - | - | 18.2% | - | - |

| Personality Disorder | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obsessive-Compulsive | Borderline | Avoidant | Dependent | Antisocial | Narcissistic | Paranoid | |

| Cassiello-Robbins et al. (2020) a (N = 49) | 10.2% | 12.2% | 8.2% | - | - | - | - |

| Jager et al. (2020) a (N = 575) | 2.4% | 1.7% | 0.5% | 0.2% | 0.2% | - | - |

| Rosenthal et al. (2022) a (N = 207) | 5.8% | 2.9% | 2.9% | 0.5% | - | 0.5% | 0.5% |

| Schröder et al. (2013) a (N = 42) | 52.4% | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodrigues, A.L.M.; Aazh, H. Psychiatric Comorbidities in Hyperacusis and Misophonia: A Systematic Review. Audiol. Res. 2025, 15, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15040101

Rodrigues ALM, Aazh H. Psychiatric Comorbidities in Hyperacusis and Misophonia: A Systematic Review. Audiology Research. 2025; 15(4):101. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15040101

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodrigues, Ana Luísa Moura, and Hashir Aazh. 2025. "Psychiatric Comorbidities in Hyperacusis and Misophonia: A Systematic Review" Audiology Research 15, no. 4: 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15040101

APA StyleRodrigues, A. L. M., & Aazh, H. (2025). Psychiatric Comorbidities in Hyperacusis and Misophonia: A Systematic Review. Audiology Research, 15(4), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15040101