Body Image Concerns and Psychological Distress in Adults with Hearing Aids: A Case-Control Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Audiologic Assessment

2.2. Body Mass Index

2.3. Questionnaires

- -

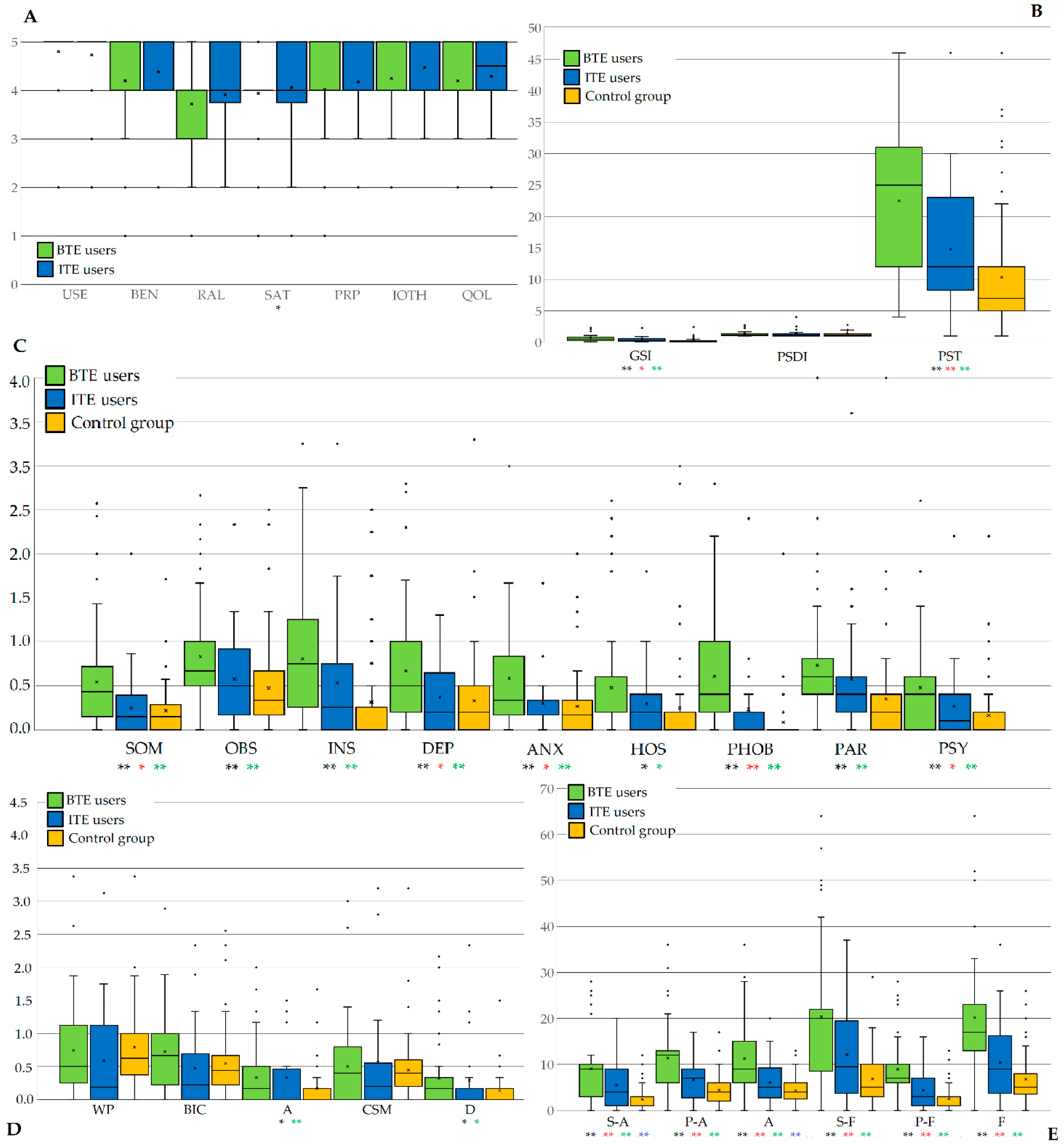

- The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) [31,32]. BSI assesses the psychological response and distress to physical illness and disability. In detail, it consists of 53 items that measure somatization (SOM), obsessive-compulsivity (OBS), interpersonal sensitivity (INS), depression (DEP), anxiety (ANX), hostility (HOS), phobic anxiety (PHOB), paranoid ideation (PAR), and psychoticism (PSY). The nine dimensions can be summed up to reflect three global indices: Global Severity Index (GSI), Positive Symptom Total (PST) and Positive Symptom Distress Index (PSDI). The GSI is calculated using the sums for the nine symptom dimensions and dividing by the total number of items. It is a sensitive indicator of the overall level of distress. The PST is a count of all the items with non-zero responses and reveals the absolute number of endorsed symptoms. The PSDI is the sum of the values of the items receiving non-zero responses divided by the PST. It provides information about the average level of distress the respondent experiences.The items are then rated, from 0 (‘not at all’) to 4 (‘extremely’), ranking the distress intensity in the last week.

- -

- The Body Uneasiness Test (BUT) [33]. This instrument is a psychometric assessment of body image-related discomfort. In the present study, the BUT-A scale was used, containing 34 items that can be divided into the following categories: fear of being or becoming fat (Weight phobia—WP), concerns associated with the physical appearance (Body Image Concerns—BIC), body image related to avoidance conduct (Avoidance—A), compulsive evaluation of physical features (Compulsive Self-Monitoring—CSM) and estrangement body feelings (Depersonalization—D). Each item is rated on a six-point Likert-type scale ranging 0–5 (from ‘never’ to ‘always’) and high rates indicate greater bodily discomfort. The BUT-B, which looks at specific worries about particular body parts or functions, was not used in the present study.

- -

- The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) [34,35]. It is a scale that considers the social and performance difficulties involved in phobic disorder. The LSAS consists of 24 items, 11 of which explore social interaction and 13 actual situations. For each item, the amount of fear and avoidance related to the given scenario must be indicated, with a rating from 0 to 3 on a Likert scale. The total score expressed on 48 answers indicates increasing social anxiety and can be divided into the two fear (F) and avoidance (A) subscales, which in each case are composed of social interaction (S-F and S-Av) and performance domains (P-F and P-A). According to the authors, a total score ranging 30–50 indicates mild social anxiety, whereas scores 50–65 or 65–80 are consistent with moderate and marked social anxiety.

- -

- The International Outcome Inventory for Hearing Aids (IOI-HA), Italian version, was proposed to the case group [36,37]. It consists of seven items regarding the outcome domains of specific item tests for assisted hearing device carriers, including the following subscales: Daily Use (USE), Benefit (BEN), Residual Activity Limitation (RAL), Satisfaction (SAT), Residual Participation Restrictions (RPR), Impact on others (IOTH), and Quality of life (QOL). Each item has five response choices, on a Likert scale, ranging from 1 (least favorable) to 5 (most favorable). Therefore, the score ranges from 7 to 35. The higher the total score of the scale, the higher the degree of patients’ satisfaction with their hearing aids. The Cronbach’s α on the original version was 0.78 and this instrument was also later translated in Italian [38,39].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Major, B.; O’Brien, L.T. The social psychology of stigma. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2005, 56, 393–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, L.A.; Rueda, S.; Baker, D.N.; Wilson, M.G.; Deutsch, R.; Raeifar, E.; Rourke, S.B.; Stigma Review Team. Stigma, HIV and health: A qualitative synthesis. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammarlund, R.; Crapanzano, K.A.; Luce, L.; Mulligan, L.; Ward, K.M. Review of the effects of self-stigma and perceived social stigma on the treatment-seeking decisions of individuals with drug- and alcohol-use disorders. Subst. Abuse Rehabil. 2018, 9, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puhl, R.M.; Heuer, C.A. Obesity stigma: Important considerations for public health. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, C.; Evans-Lacko, S.; Thornicroft, G. Mental illness stigma, help seeking, and public health programs. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 777–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruusuvuori, J.E.; Aaltonen, T.; Koskela, I.; Ranta, J.; Lonka, E.; Salmenlinna, I.; Laakso, M. Studies on stigma regarding hearing impairment and hearing aid use among adults of working age: A scoping review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021, 43, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, J.C.; de Araujo, C.M.; Lüders, D.; Santos, R.S.; Moreira de Lacerda, A.B.; José, M.R.; Guarinello, A.C. The Self-Stigma of Hearing Loss in Adults and Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Ear Hear. 2023, 44, 1301–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, D.; Werner, P. Stigma regarding hearing loss and hearing aids: A scoping review. Stigma Health 2016, 1, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, A.; Fortnum, H. Why Do People Fitted with Hearing Aids not Wear Them? Int. J. Audiol. 2013, 52, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, A.B.; Leighton, P.; Ferguson, M.A. Coping together with hearing loss: A qualitative meta-synthesis of the psychosocial experiences of people with hearing loss and their communication partners. Int. J. Audiol. 2017, 56, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kochkin, S. MarkeTrak III: Why 20 million in US don’t use hearing aids for their hearing loss. Hear. J. 1993, 46, 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Erler, S.F.; Garstecki, D.C. Hearing loss- and hearing aid-related stigma: Perceptions of women with age-normal hearing. Am. J. Audiol. 2002, 11, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauterkus, E.P.; Palmer, C.V. The hearing aid effect in 2013. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2014, 25, 893–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, R.M.; Johnson, J.A.; Xu, J. Impact of Hearing Aid Technology on Outcomes in Daily Life I: The Patients’ Perspective. Ear Hear. 2016, 37, e224–e237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Heffernan, E.; Coulson, N.S.; Henshaw, H.; Barry, J.G.; Ferguson, M.A. Understanding the psychosocial experiences of adults with mild-moderate hearing loss: An application of Leventhal’s self-regulatory model. Int. J. Audiol. 2016, 55 (Suppl. 3), S3–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wallhagen, M.I. The stigma of hearing loss. Gerontologist 2010, 50, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Marcos-Alonso, S.; Almeida-Ayerve, C.N.; Monopoli-Roca, C.; Coronel-Touma, G.S.; Pacheco-López, S.; Peña-Navarro, P.; Serradilla-López, J.M.; Sánchez-Gómez, H.; Pardal-Refoyo, J.L.; Batuecas-Caletrío, Á. Factors Impacting the Use or Rejection of Hearing Aids-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickbakht, M.; Ekberg, K.; Waite, M.; Scarinci, N.; Timmer, B.; Meyer, C.; Hickson, L. The experience of stigma related to hearing loss and hearing aids: Perspectives of adults with hearing loss, their families, and hearing care professionals. Int. J. Audiol. 2024, 64, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beadle, J.; Jenstad, L.; Cochrane, D.; Small, J. Perceptions of older and younger adults who wear hearing aids. Int. J. Audiol. 2024. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, P. Consumer segmentation research yields a personalized way to select hearing aids. Hear. J. 2009, 62, 24–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, R.F.; Laveway, K.; Campos, P.; de Carvalho, P.H.B. Body image as a global mental health concern. Camb. Prisms Glob. Ment. Health 2023, 10, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarry, J.L.; Dignard, N.A.L.; O’Driscoll, L.M. Appearance investment: The construct that changed the field of body image. Body Image 2019, 31, 221–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, K.; Giorgianni, F.E.; Danthinne, E.S.; Rodgers, R.F. Beauty ideals, social media, and body positivity: A qualitative investigation of influences on body image among young women in Japan. Body Image 2021, 38, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satici, S.; Derinsu, U.; Akdeniz, E. Evaluation of self-esteem in hearing aid and cochlear implant users. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2023, 280, 2735–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, S.; Çiprut, A.A. The body image in hearing aid and cochlear implant users in Turkey. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2022, 279, 5199–5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eleuteri, F.; Forghieri, M.; Ferrari, S.; Marrara, A.; Monzani, D.; Rigatelli, M. P01-269—Psychopathological Distress, Body Image Perception and Social Phobia in Patients with Hearing Aids and Cochlear Implants. Eur. Psychiatry 2010, 25, 25-E477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.G. Uses and abuses of hearing loss classification. ASHA 1981, 23, 493–500. [Google Scholar]

- Turrini, M.; Cutugno, F.; Maturi, P.; Prosser, S. Nuove parole bisillabiche per audiometria vocale in lingua italiana. Acta Otorhinol. Ital. 1993, 13, 63–77. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Global Infobase Team. The SuRF Report 2. Surveillance of Chronic Disease Risk Factors: Country-Level Data and Comparable Estimates; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005; Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/43190/9241593024_eng.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Quittkat, H.L.; Hartmann, A.S.; Düsing, R.; Buhlmann, U.; Vocks, S. Body Dissatisfaction, Importance of Appearance, and Body Appreciation in Men and Women Over the Lifespan. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derogatis, L.R.; Melisaratos, N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: An introductory report. Psychol. Med. 1983, 13, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adawi, M.; Zerbetto, R.; Re, T.S.; Bisharat, B.; Mahamid, M.; Amital, H.; Del Puente, G.; Bragazzi, N.L. Psychometric properties of the Brief Symptom Inventory in nomophobic subjects: Insights from preliminary confirmatory factor, exploratory factor, and clustering analyses in a sample of healthy Italian volunteers. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2019, 12, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuzzolaro, M.; Vetrone, G.; Marano, G.; Garfinkel, P.E. The Body Uneasiness Test (BUT): Development and validation of a new body image assessment scale. Eat. Weight Disord. 2006, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebowitz, M.R. Social phobia. Mod. Probl. Pharmacopsychiatry 1987, 22, 141–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baroni, D.; Caccico, L.; Ciandri, S.; Di Gesto, C.; Di Leonardo, L.; Fiesoli, A.; Grassi, E.; Lauretta, F.; Lebruto, A.; Marsigli, N.; et al. Measurement invariance of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale-Self-Report. J. Clin. Psychol. 2023, 79, 391–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, R.; Hyde, M.; Gatehouse, S.; Noble, W.; Dillon, H.; Bentler, R.; Stephens, D.; Arlinger, S.; Beck, L.; Wilkerson, D.; et al. Optimal outcome measures, research priorities, and international cooperation. Ear Hear. 2000, 21 (Suppl. 4), 106S–115S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, R.M.; Stephens, D.; Kramer, S.E. Translations of the International Outcome inventory for Hearing Aids (IOI-HA). Int. J. Audiol. 2002, 41, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, R.M.; Alexander, G.C. The International Outcome Inventory for Hearing Aids (IOI-HA): Psychometric properties of the English version. Int. J. Audiol. 2002, 41, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoham, N.; Lewis, G.; Favarato, G.; Cooper, C. Prevalence of anxiety disorders and symptoms in people with hearing impairment: A systematic review. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2019, 54, 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachtegaal, J.; Smit, J.H.; Smits, C.; Bezemer, P.D.; van Beek, J.H.; Festen, J.M.; Kramer, S.E. The association between hearing status and psychosocial health before the age of 70 years: Results from an internet-based national survey on hearing. Ear Hear. 2009, 30, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.C.; Falkum, E.; Martinsen, E.W. Fear of negative evaluation, avoidance and mental distress among hearing-impaired employees. Rehabil. Psychol. 2015, 60, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carney, D.R.; Harrigan, J.A. It takes one to know one: Interpersonal sensitivity is related to accurate assessments of others’ interpersonal sensitivity. Emotion 2003, 3, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prnjak, K.; Jukic, I.; Mitchison, D.; Griffiths, S.; Hay, P. Body image as a multidimensional concept: A systematic review of body image facets in eating disorders and muscle dysmorphia. Body Image 2022, 42, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garner, D.M.; Strachan-Kinser, M.; Bakke, B.; Clauss, L.J.; Phillips, K.A. Multidimensional body image comparisons among patients with eating disorders, body dimorphic disorder, and clinical controls: A multisite study. Body Image 2009, 6, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurkiewicz, N.; Krefta, J.; Lipowska, M. Attitudes Towards Appearance and Body-Related Stigma Among Young Women With Obesity and Psoriasis. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 788439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawes, P.; Maslin, M.; Munro, K.J. ‘Getting used to’ hearing aids from the perspective of adult hearing-aid users. Int. J. Audiol. 2014, 53, 861–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumfield, A.; Dillon, H. Factors affecting the use and perceived benefit of ITE and BTE hearing aids. Br. J. Audiol. 2001, 35, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desjardins, J.L.; Doherty, K.A. Changes in Psychosocial Measures After a 6-Week Field Trial. Am. J. Audiol. 2017, 26, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, N.; Beukes, E.W.; Manchaiah, V.; Mahomed-Asmail, F.; Swanepoel, W. Consumer Perspectives on Improving Hearing Aids: A Qualitative Study. Am. J. Audiol. 2024, 33, 728–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madara, E.; Bhowmik, A.K. Toward Alleviating the Stigma of Hearing Aids: A Review. Audiol. Res. 2024, 14, 1058–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallari, V.; Liberale, C.; De Cecco, F.; Monzani, D. Can ChatGPT be a valuable study tool for ENT residents? Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2024, 141, 189–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Mavrommatis, M.M.; Govindan, A.; Cosetti, M.K. The Stigma of Hearing Loss: A Scoping Review of the Literature Across Age and Gender. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2025. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virdi, J. Deaf futurity: Designing and innovating hearing aids. Med. Humanit. 2025, 50, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Case Group (n = 96) | Control Group (n = 85) | Significance a,b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 57.31 (36–65; SD ± 9.34) | 58.39 (33–65; SD ± 9.21) | 0.354 a |

| Gender | 46 (47.8%) females 50 (52.2%) males | 43 (50.6%) females 42 (49.4%) males | 0.720 b |

| Marital Status | 56 (58.3%) singles 40 (41.7%) married | 53 (62.4%) singles 32 (37.7%) married | 0.581 b |

| Educational qualification | 54 (56.2%) primary school 21 (21.9%) high school 21 (21.9%) university | 46 (54.1%) primary school 23 (27.1%) high school 16 (18.8%) university | 0.741 b |

| BMI | 23.70 (18.37–38.22; ± SD 4.07) | 24.73 (19.53–30.59; SD ± 3.22 SD | 0.053 a |

| Case Group (n = 96) | Control Group (n = 85) | Significance a,b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GSI | 0.53 (0.06–2.33; SD ± 0.50) | 0.28 (0.19–2.42; SD ± 0.36) | ** 0.001 a |

| PSDI | 1.33 (1.00–4.00; SD ± 0.51) | 1.27 (1.00–2.78; SD ± 0.33) | 0.118 a |

| PST | 19.61 (0.00–46; SD ± 11.96) | 10.32 (1.00–46; SD ± 9.28) | ** 0.000 a |

| SOM | 0.44 (0.00–2.57; SD ± 0.54) | 0.22 (0.00–1.71; SD ± 0.29) | ** 0.001 a |

| OBS | 0.73 (0.00–2.67; SD ± 0.58) | 0.47 (0.00–2.50; SD ± 0.51) | 0.067 a |

| INS | 0.70 (0.00–3.25; SD ± 0.75) | 0.31 (0.00–2.50; SD ± 0.53) | ** 0.002 a |

| DEP | 0.55 (0.00–2.80; SD ± 0.59) | 0.32 (0.00–3.33; SD ± 0.50) | * 0.026 a |

| ANX | 0.48 (0.00–3.00; SD ± 0.59) | 0.26 (0.00–2.00; SD ± 0.37) | ** 0.000 a |

| HOS | 0.41 (0.00–2.60; SD ± 0.56) | 0.25 (0.00–3.00; SD ± 0.49) | 0.103 a |

| PHOB | 0.47 (0.00–2.80; SD ± 0.60) | 0.09 (0.00–2.00;SD ± 0.25) | ** 0.000 a |

| PAR | 0.70 (0.00–4.00; SD ± 0.66) | 0.35 (0.00–4.00; SD ± 0.57) | 0.130 a |

| PSY | 0.40 (0.00–2.60; SD ± 0.53) | 0.16 (0.00–2.20; SD ± 0.33) | ** 0.000 a |

| Case Group (n = 96) | Control Group (n = 85) | Significance a,b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WP | 0.68 (0.0–3.38; SD ± 0.74) | 0.80 (0.0–4.38; SD ± 0.69) | * 0.025 a |

| BIC | 0.63 (0.0–2.89; SD ± 0.68) | 0.55 (0.0–2.55; SD ± 0.52) | ** 0.001 a |

| A | 0.34 (0.0–2.00; SD ± 0.47) | 0.17 (0.0–1.67; SD ± 0.32) | ** 0.001 a |

| CSM | 0.52 (0.0–3.20; SD ± 0.75) | 0.45 (0.0–3.20; SD ± 0.45) | ** 0.000 a |

| D | 0.31 (0.0–2.33; SD ± 0.52) | 0.14 (0.0–1.50; SD ± 0.28) | ** 0.000 a |

| Case Group (n = 96) | Control Group (n = 85) | Significance a,b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| S-A | 7.72 (0–28; SD ± 7.72) | 2.40 (0–12; SD ± 2.66) | ** 0.000 a |

| P-A | 9.64 (0–36; SD ± 9.64) | 4.45 (0–17; SD ± 3.34) | ** 0.000 a |

| A | 17.35 (0–64; SD ± 17.35) | 6.85 (0–29; SD ± 5.69) | ** 0.000 a |

| S-F | 7.28 (0–28; SD ± 7.28) | 2.52 (0–13; SD ± 3.07) | ** 0.001 a |

| P-F | 9.35 (0–36; SD ± 9.35) | 4.32 (0–13; SD ± 2.73) | ** 0.000 a |

| F | 16.64 (0–64; SD ± 16.64) | 6.84 (0–26; SD ± 5.52) | ** 0.000 a |

| LSAS | 33.99 (0–128; SD ± 33.99) | 13.68 (0–52; SD ± 10.67) | ** 0.000 a |

| 18–40 Years Old (n = 22) | 41–65 Years Old (n = 74) | Significance a,b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GSI | 0.60 (0.11–2.34; ±0.56) | 0.51 (0.06–2.26; ±0.48) | 0.465 a |

| PSDI | 1.25 (1.00–2.70; ±0.43) | 1.36 (1.00–4.00; ±0.53) | 0.390 a |

| PST | 22.45 (6–46; ±13.51) | 18.77 (1–46; ±11.41) | 0.206 a |

| WP | 0.59 (0.0–1.62; ±0.53) | 0.71 (0.0–3.38; ±0.79) | 0.512 a |

| BIC | 0.66 (0.0–1.22; ±0.47) | 0.62 (0.0–2.89; ±0.73) | 0.826 a |

| A | 0.12 (0.0–0.50 ±0.18) | 0.41 (0.0–2.00; ±0.50) | * 0.011 a |

| CSM | 0.36 (0.0–1.40. ±0.39) | 0.57 (0.0–3.20; ±0.82) | 0.270 a |

| D | 0.11 (0.0–0.50; ±0.17) | 0.37 (0.0–2.33; ±0.57) | * 0.036 a |

| S-A | 8.50 (2–21; ±5.09) | 7.49 (0–28; ±7.09) | 0.534 a |

| P-A | 9.55 (3–21; ±4.76) | 9.66 (0–36; ±7.61) | 0.946 a |

| A | 18.05 (5–42; ±9.81) | 17.15 (0–64; ±14.44) | 0.786 a |

| S-F | 7.95 (2–17; ±3.44) | 7.08 (0–28; ±6.43) | 0.543 a |

| P-F | 9.41 (4–16; ±4.61) | 9.34 (0–36; ±7.64) | 0.967 a |

| F | 17.36 (7–33; ±7.30) | 16.42 (0–64; ±13.86) | 0.760 a |

| LSAS | 35.41 (12–75; ±16.48) | 33.57 (0–128; ±27.78) | 0.769 a |

| Case Group (n = 96) | 18–40 Years Old (n = 22) | 41–65 Years Old (n = 74) | Significance a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USE | 4.78 (2–5; ±0.57) | 4.82 (4–5; ±0.40) | 4.77 (2–5; ±0.61) | 0.729 a |

| BEN | 4.27 (1–5; ±1.04) | 4.41 (3–5; ±0.67) | 4.23 (1–5; ±1.14) | 0.481 a |

| RAL | 3.77 (1–5; ±1.04) | 4.05 (4–5; ±0.21) | 3.69 (1–5; ±1.17) | ** 0.015 a |

| SAT | 3.98 (1–5; ±0.87) | 4.14 (4–5; ±0.35) | 3.93 (1–5; ±0.97) | 0.135 a |

| RPR | 4.07 (1–5; ±0.93) | 4.09 (3–5; ±0.75) | 4.07 (1–5; ±0.98) | 0.914 a |

| IOTH | 4.33 (2–5; ±0.69) | 4.64 (4–5; ±0.49) | 4.24 (2–5; ±0.72) | * 0.005 a |

| QOL | 4.23 (2–5; ±0.76) | 4.18 (3–5; ±0.59) | 4.24 (2–5; ±0.81) | 0.741 a |

| TOT | 29.44 (13–35; ±4.31) | 30.32 (27–35; ±1.59) | 29.18 (13–35; ±4.81) | 0.084 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Apa, E.; Ferrari, S.; Monzani, D.; Ciorba, A.; Sacchetto, L.; Dallari, V.; Nocini, R.; Palma, S. Body Image Concerns and Psychological Distress in Adults with Hearing Aids: A Case-Control Study. Audiol. Res. 2025, 15, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15030062

Apa E, Ferrari S, Monzani D, Ciorba A, Sacchetto L, Dallari V, Nocini R, Palma S. Body Image Concerns and Psychological Distress in Adults with Hearing Aids: A Case-Control Study. Audiology Research. 2025; 15(3):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15030062

Chicago/Turabian StyleApa, Enrico, Silvia Ferrari, Daniele Monzani, Andrea Ciorba, Luca Sacchetto, Virginia Dallari, Riccardo Nocini, and Silvia Palma. 2025. "Body Image Concerns and Psychological Distress in Adults with Hearing Aids: A Case-Control Study" Audiology Research 15, no. 3: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15030062

APA StyleApa, E., Ferrari, S., Monzani, D., Ciorba, A., Sacchetto, L., Dallari, V., Nocini, R., & Palma, S. (2025). Body Image Concerns and Psychological Distress in Adults with Hearing Aids: A Case-Control Study. Audiology Research, 15(3), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15030062