Appropriate Treatment Intensity for Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma in the Older Population: A Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Chemotherapy Options

3. Considerations in the Older Population

4. Management of Frail, Older Patients

5. Reduced-Intensity Chemotherapy

6. New, Novel, and Chemotherapy-Free Regimens

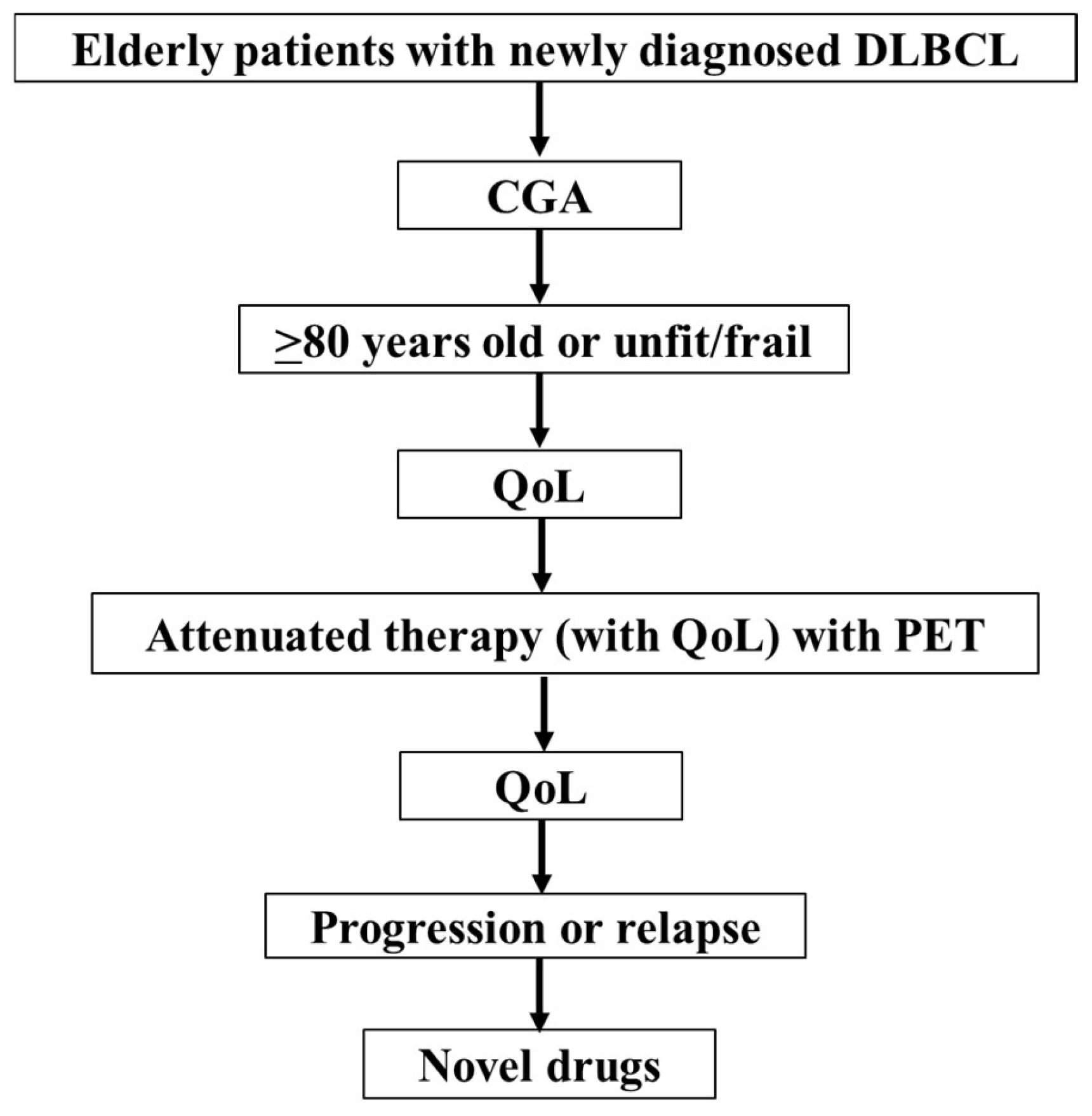

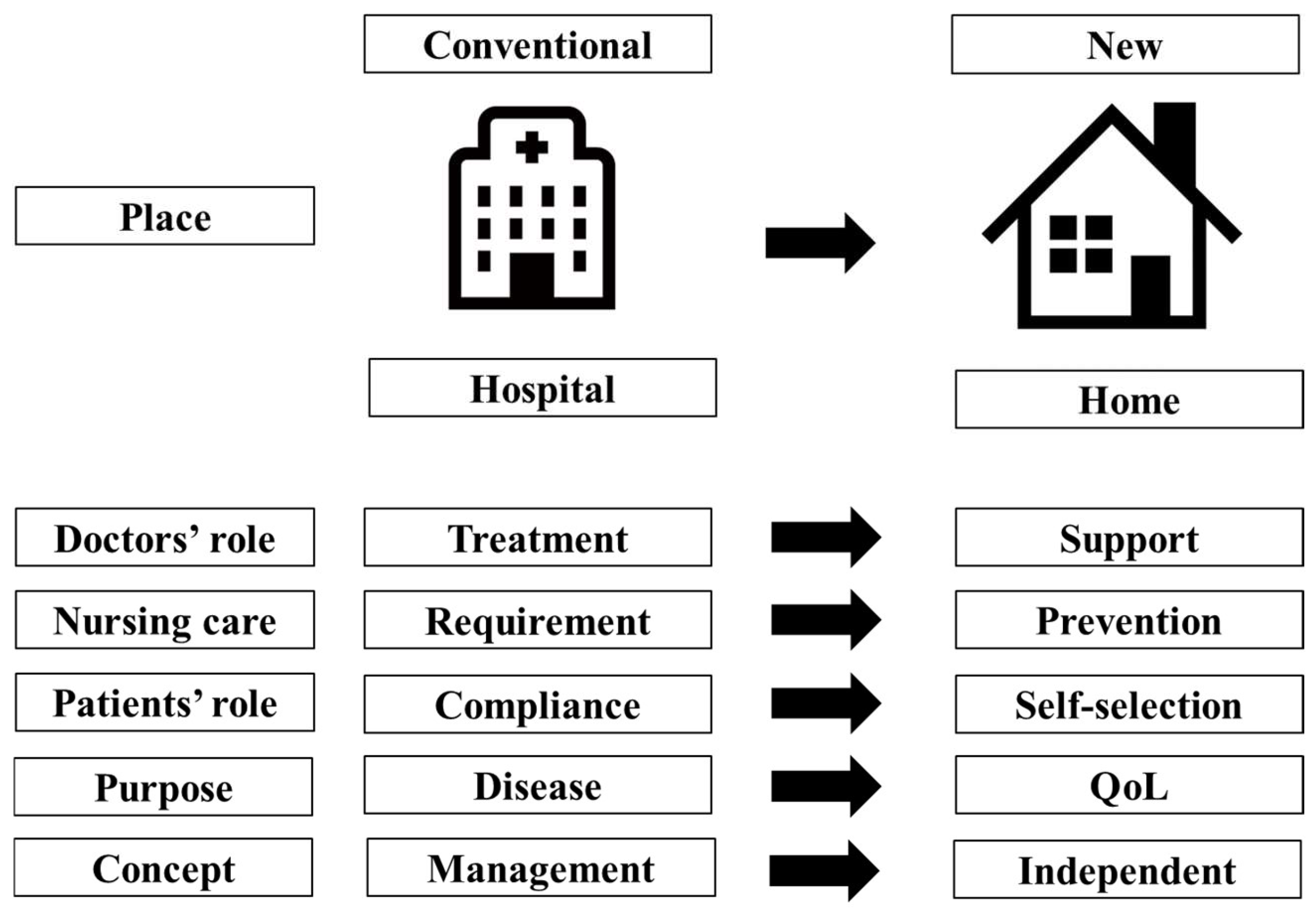

7. Geriatric and QoL Assessments, and Tailoring Therapy in DLBCL

8. Future Directions and Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coiffier, B.; Lepage, E.; Brière, J.; Herbrecht, R.; Tilly, H.; Bouabdallah, R.; Morel, P.; Van Den Neste, E.; Salles, G.; Gaulard, P.; et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goy, A. Succeeding in breaking the R-CHOP ceiling in DLBCL: Learning from negative trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 3519–3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younes, A.; Sehn, L.H.; Johnson, P.; Zinzani, P.L.; Hong, X.; Zhu, J.; Patti, C.; Belada, D.; Samoilova, O.; Suh, C.; et al. Randomized phase III trial of ibrutinib and rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone in non–germinal center B-cell diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 1285–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowakowski, G.S.; Chiappella, A.; Gascoyne, R.D.; Scott, D.W.; Zhang, Q.; Jurczak, W.; Özcan, M.; Hong, X.; Zhu, J.; Jin, J.; et al. ROBUST: A Phase III Study of Lenalidomide Plus R-CHOP Versus Placebo Plus R-CHOP in Previously Untreated Patients with ABC-Type Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 1317–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilly, H.; Morschhauser, F.; Sehn, L.H.; Friedberg, J.W.; Trněný, M.; Sharman, J.P.; Herbaux, C.; Burke, J.M.; Matasar, M.; Rai, S.; et al. Polatuzumab vedotin in previously untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedberg, J.W. How I treat double-hit lymphoma. Blood 2017, 130, 590–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oki, Y.; Noorani, M.; Lin, P.; Davis, R.E.; Neelapu, S.S.; Ma, L.; Ahmed, M.; Rodriguez, M.A.; Hagemeister, F.B.; Fowler, N.; et al. Double hit lymphoma: The MD Anderson cancer center clinical experience. Br. J. Haematol. 2014, 166, 891–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodero, A.; Guidetti, A.; Tucci, A.; Barretta, F.; Novo, M.; Devizzi, L.; Re, A.; Passi, A.; Pellegrinelli, A.; Pruneri, G.; et al. Dose-adjusted EPOCH plus rituximab improves the clinical outcome of young patients affected by double expressor diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leukemia 2019, 33, 1047–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, R.; Wright, G.W.; Huang, D.W.; Johnson, C.A.; Phelan, J.D.; Wang, J.Q.; Roulland, S.; Kasbekar, M.; Young, R.M.; Shaffer, A.L.; et al. Genetics and pathogenesis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1396–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehn, L.H.; Salles, G. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 842–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanibar-Adaniya, S.; Barta, S.K. 2021 Update on diffuse large B cell lymphoma: A review of current data and potential applications on risk stratification and management. Am. J. Hematol. 2021, 96, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persky, D.O.; Li, H.; Stephens, D.M.; Park, S.I.; Bartlett, N.L.; Swinnen, L.J.; Barr, P.M.; Winegarden, J.D.; Constine, L.S.; Fitzgerald, T.J.; et al. Positron emission tomography-directed therapy for patients with limited-stage diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Results of Intergroup National Clinical Trials Network Study S1001. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 3003–3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilly, H.; Gomes da Silva, M.; Vitolo, U.; Jack, A.; Meignan, M.; Lopez-Guillermo, A.; Walewski, J.; André, M.; Johnson, P.W.; Pfreundschuh, M.; et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL): ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26 (Suppl. 5), v116–v125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): B-Cell Lymphomas. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/b-cell.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2023).

- Alvarez, R.; Esteves, S.; Chacim, S.; Carda, J.; Mota, A.; Guerreiro, M.; Barbosa, I.; Moita, F.; Teixeira, A.; Coutinho, J.; et al. What determines therapeutic choices for elderly patients with DLBCL? Clinical findings of a multicenter study in Portugal. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2014, 14, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyon, A.R.; Dent, S.; Stanway, S.; Earl, H.; Brezden-Masley, C.; Cohen-Solal, A.; Tocchetti, C.G.; Moslehi, J.J.; Groarke, J.D.; Bergler-Klein, J.; et al. Baseline cardiovascular risk assessment in cancer patients scheduled to receive cardiotoxic cancer therapies: A position statement and new risk assessment tools from the cardio-oncology study group of the heart failure association of the European society of cardiology in collaboration with the international cardio-oncology society. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2020, 22, 1945–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moccia, A.A.; Thieblemont, C. Curing diffuse large B-cell lymphomas in elderly patients. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 58, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, P.-H.; Kuo, C.-Y.; Ma, M.-C.; Liao, C.-K.; Pei, S.-N.; Wang, M.-C. Oral chemotherapy application in elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: An alternative regimen in retrospective analysis. J. Hematol. 2022, 11, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkozy, C.; Coiffier, B. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the elderly: A review of potential difficulties. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 1660–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Jo, J.-C.; Do, Y.R.; Yang, D.-H.; Lim, S.-N.; Lee, W.-S.; Kim, W.S.; Lee, H.S.; Hong, D.-S.; Kim, H.J.; et al. Multicenter phase 2 study of reduced-dose CHOP chemotherapy combined with rituximab for elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2019, 19, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyre, T.A.; Wilson, W.; Kirkwood, A.A.; Wolf, J.; Hildyard, C.; Plaschkes, H.; Griffith, J.; Fields, P.; Gunawan, A.; Oliver, R.; et al. Infection-related morbidity and mortality among older patients with DLBCL treated with full- or attenuated-dose R-CHOP. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 2229–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenwald, A.; Wright, G.; Chan, W.C.; Connors, J.M.; Campo, E.; Fisher, R.I.; Gascoyne, R.D.; Muller-Hermelink, H.K.; Smeland, E.B.; Giltnane, J.M.; et al. The use of molecular profiling to predict survival after chemotherapy for diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 1937–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niiyama-Uchibori, Y.; Okamoto, H.; Miyashita, A.; Mizuhara, K.; Kanayama-Kawaji, Y.; Fujino, T.; Tsukamoto, T.; Mizutani, S.; Shimura, Y.; Teramukai, S.; et al. Skeletal muscle index impacts the treatment outcome of elderly patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 42, e3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feugier, P.; Van Hoof, A.; Sebban, C.; Solal-Celigny, P.; Bouabdallah, R.; Fermé, C.; Christian, B.; Lepage, E.; Tilly, H.; Morschhauser, F.; et al. Long-term results of the R-CHOP Study in the treatment of elderly patients with diffuse large b-cell lymphoma: A study by the Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 4117–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasterlid, T.; Oren Gradel, K.; Eloranta, S.; Glimelius, I.; El-Galaly, T.C.; Frederiksen, H.; Smedby, K.E. Clinical characteristics and outcomes among 2347 patients aged ≥85 years with major lymphoma subtypes: A Nordic Lymphoma Group study. Br. J. Haematol. 2021, 192, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataillard, E.J.; Cheah, C.Y.; Maurer, M.J.; Khurana, A.; Eyre, T.A.; El-Galaly, T.C. Impact of R-CHOP dose intensity on survival outcomes in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A systematic review. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 2426–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sarayfi, D.; Brink, M.; Chamuleau, M.E.D.; Brouwer, R.; van Rijn, R.S.; Issa, D.; Deenik, W.; Huls, G.; Mous, R.; Vermaat, J.S.P.; et al. R-miniCHOP versus R-CHOP in elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A propensity matched population-based study. Am. J. Hematol. 2024, 99, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyrade, F.; Jardin, F.; Thieblemont, C.; Thyss, A.; Emile, J.-F.; Castaigne, S.; Coiffier, B.; Haioun, C.; Bologna, S.; Fitoussi, O.; et al. Attenuated immunochemotherapy regimen (R-miniCHOP) in elderly patients older than 80 years with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyrade, F.; Bologna, S.; Delwail, V.; Emile, J.F.; Pascal, L.; Fermé, C.; Schiano, J.-M.; Coiffier, B.; Corront, B.; Farhat, H.; et al. Combination of ofatumumab and reduced-dose CHOP for diffuse large B-cell lymphomas in patients aged 80 years or older: An open-label, multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial from the LYSA group. Lancet Haematol. 2017, 4, e46–e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfreundschuh, M.; Trümper, L.; Kloess, M.; Schmits, R.; Feller, A.C.; Rübe, C.; Rudolph, C.; Reiser, M.; Hossfeld, D.K.; Eimermacher, H.; et al. Two-weekly or 3-weekly CHOP chemotherapy with or without etoposide for the treatment of elderly patients with aggressive lymphomas: Results of the NHL-B2 trial of the DSHNHL. Blood 2004, 104, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershman, D.L.; McBride, R.B.; Eisenberger, A.; Tsai, W.Y.; Grann, V.R.; Jacobson, J.S. Doxorubicin, cardiac risk factors, and cardiac toxicity in elderly patients with diffuse B-cell non-hodgkin’s lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 3159–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luminari, S.; Montanini, A.; Caballero, D.; Bologna, S.; Notter, M.; Dyer, M.J.S.; Chiappella, A.; Briones, J.; Petrini, M.; Barbato, A.; et al. Nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin (Myocet™) combination (R-COMP) chemotherapy in elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL): Results from the phase II EURO18 trial. Ann. Oncol. 2010, 21, 1492–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sancho, J.M.; Fernández-Alvarez, R.; Gual-Capllonch, F.; González-García, E.; Grande, C.; Gutiérrez, N.; Peñarrubia, M.; Batlle-López, A.; González-Barca, E.; Guinea, J.; et al. R-COMP versus R-CHOP as first-line therapy for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in patients ≥60 years: Results of a randomized phase 2 study from the Spanish GELTAMO group. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 1314–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigacci, L.; Annibali, O.; Kovalchuk, S.; Bonifacio, E.; Pregnolato, F.; Angrilli, F.; Vitolo, U.; Pozzi, S.; Broggi, S.; Luminari, S.; et al. Nonpeghylated liposomal doxorubicin combination regimen (R-COMP) for the treatment of lymphoma patients with advanced age or cardiac comorbidity. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 38, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visco, C.; Pregnolato, F.; Ferrarini, I.; De Marco, B.; Bonuomo, V.; Sbisà, E.; Fraenza, C.; Bernardelli, A.; Tanasi, I.; Quaglia, F.M.; et al. Efficacy of R-COMP in comparison to R-CHOP in patients with DLBCL: A systematic review and single-arm metanalysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2021, 163, 103377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laribi, K.; Denizon, N.; Bolle, D.; Truong, C.; Besançon, A.; Sandrini, J.; Anghel, A.; Farhi, J.; Ghnaya, H.; de Materre, A.B. R-CVP regimen is active in frail elderly patients aged 80 or over with diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Ann. Hematol. 2016, 95, 1705–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucci, A.; Merli, F.; Fabbri, A.; Marcheselli, L.; Pagani, C.; Puccini, B.; Marino, D.; Zanni, M.; Pennese, E.; Flenghi, L.; et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in octogenarians aged 85 and older can benefit from treatment with curative intent: A report on 129 patients prospectively registered in the elderly project of the fondazione italiana linfomi (FIL). Haematologica 2023, 108, 1083–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storti, S.; Spina, M.; Pesce, E.A.; Salvi, F.; Merli, M.; Ruffini, A.; Cabras, G.; Chiappella, A.; Angelucci, E.; Fabbri, A.; et al. Rituximab plus bendamustine as front-line treatment in frail elderly (>70 years) patients with diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: A phase II multicenter study of the fondazione italiana linfomi. Haematologica 2018, 103, 1345–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gini, G.; Tani, M.; Bassan, R.; Tucci, A.; Ballerini, F.; Sampaolo, M.; Merli, F.; Re, F.; Olivieri, A.; Petrini, M.; et al. Lenalidomide and rituximab (ReRi) as front-line chemo-free therapy for elderly frail patients with diffuse large b-cell lymphoma. A phase II study of the fondazione italiana linfomi. Blood 2021, 138, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyre, T.A.; Martinez-Calle, N.; Hildyard, C.; Eyre, D.W.; Plaschkes, H.; Griffith, J.; Wolf, J.; Fields, P.; Gunawan, A.; Oliver, R.; et al. Impact of intended and relative dose intensity of R-CHOP in a large, consecutive cohort of elderly diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients treated with curative intent: No difference in cumulative incidence of relapse comparing patients by age. J. Intern. Med. 2019, 285, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verner, E.; Johnston, A.; Pati, N.; Hawkes, E.; Lee, H.-P.; Cochrane, T.; Cheah, C.-Y.; Filshie, R.J.; Purtill, D.; Sia, H.; et al. Efficacy of ibrutinib, rituximab and mini-CHOP in very elderly patients with newly diagnosed diffuse large b cell lymphoma: Primary analysis of the Australasian Leukaemia & Lymphoma Group NHL29 Study. Blood 2021, 138 (Suppl. 1), 304. Available online: https://ashpublications.org/blood/article/138/Supplement%201/304/479579/Efficacy-of-Ibrutinib-Rituximab-and-Mini-CHOP-in (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Jerkeman, M.; Leppä, S.; Hamfjord, J.; Brown, P.; Ekberg, S.; Ferreri, A.J.M. Initial safety data from the phase 3 POLAR BEAR trial in elderly or frail patients with diffuse large cell lymphoma, comparing R-pola-mini-CHP and R-mini-CHOP. In Proceedings of the European Hematology Association 2023 Hybrid Congress, Frankfurt, Germany, 8–11 June 2023. Abstract S227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Fraz, M.A.; Usman, M.; Malik, S.U.; Ijaz, A.; Durer, C.; Durer, S.; Tariq, M.J.; Khan, A.Y.; Qureshi, A.; et al. Treating diffuse large B cell lymphoma in the very old or frail patients. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2018, 19, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philip, T.; Guglielmi, C.; Hagenbeek, A.; Somers, R.; van der Lelie, H.; Bron, D.; Sonneveld, P.; Gisselbrecht, C.; Cahn, J.-Y.; Harousseau, J.-L.; et al. Autologous bone marrow transplantation as compared with salvage chemotherapy in relapses of chemotherapy-sensitive non-hodgkin’s lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995, 333, 1540–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gisselbrecht, C.; Glass, B.; Mounier, N.; Gill, D.S.; Linch, D.C.; Trneny, M.; Bosly, A.; Ketterer, N.; Shpilberg, O.; Hagberg, H.; et al. Salvage regimens with autologous transplantation for relapsed large b-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 4184–4190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chihara, D.; Izutsu, K.; Kondo, E.; Sakai, R.; Mizuta, S.; Yokoyama, K.; Kaneko, H.; Kato, K.; Hasegawa, Y.; Chou, T.; et al. High-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation for elderly patients with relapsed/refractory diffuse large b cell lymphoma: A nationwide retrospective study. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014, 20, 684–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, K.; Chen, B.E.; Kukreti, V.; Couban, S.; Benger, A.; Berinstein, N.; Kaizer, L.; Desjardins, P.; Mangel, J.; Zhu, L.; et al. Treatment outcomes for older patients with relapsed/refractory aggressive lymphoma receiving salvage chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation are similar to younger patients: A subgroup analysis from the phase III CCTG LY.12 trial. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munshi, P.N.; Chen, Y.; Ahn, K.W.; Awan, F.T.; Cashen, A.; Shouse, G.; Shadman, M.; Shaughnessy, P.; Zurko, J.; Locke, F.L.; et al. Outcomes of autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation in older patients with diffuse large b-cell lymphoma. Transplant. Cell Ther. 2022, 28, 487.e1–487.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wudhikarn, K.; Johnson, B.M.; Inwards, D.J.; Porrata, L.F.; Micallef, I.N.; Ansell, S.M.; Hogan, W.J.; Paludo, J.; Villasboas, J.C.; Johnston, P.B. Outcomes of Older Adults with Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Undergoing Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation: A Mayo Clinic Cohort Analysis. Transplant. Cell Ther. 2023, 29, 176.e1–176.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vic, S.; Lemoine, J.; Armand, P.; Lemonnier, F.; Houot, R. Transplant-ineligible but chimeric antigen receptor T-cells eligible: A real and relevant population. Eur. J. Cancer 2022, 175, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuendorff, N.R.; Khan, A.; Ullrich, F.; Yates, S.; Devarakonda, S.; Lin, R.J.; von Tresckow, B.; Cordoba, R.; Artz, A.; Rosko, A.E. Cellular therapies in older adults with hematological malignancies: A case-based, state-of-the-art review. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2024, 15, 101734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mougiakakos, D.; Voelkl, S.; Bach, C.; Stoll, A.; Bitterer, K.; Beier, F.; Endell, J.; Boxhammer, R.; Bittenbring, J.T.; Mackensen, A.; et al. Mechanistic characterization of tafasitamab-mediated antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis alone or in combination with lenalidomide. Blood 2019, 134, 4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salles, G.; Duell, J.; Gonzalez-Barca, E.; Tournilhac, O.; Jurczak, W.; Liberati, A.M.; Nagy, Z.; Obr, A.; Gaidano, G.; Andre, M.; et al. Tafasitamab plus lenalidomide in relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (L-MIND): A multicentre, prospective, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 978–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duell, J.; Maddocks, K.J.; González-Barca, E.; Jurczak, W.; Liberati, A.M.; de Vos, S.; Nagy, Z.; Obr, A.; Gaidano, G.; Abrisqueta, P.; et al. Long-term outcomes from the phase II L-MIND study of tafasitamab (MOR208) plus lenalidomide in patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Haematologica 2021, 106, 2417–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammarchi, F.; Corbett, S.; Adams, L.; Tyrer, P.C.; Kiakos, K.; Janghra, N.; Marafioti, T.; Britten, C.E.; Havenith, C.E.G.; Chivers, S.; et al. ADCT-402, a PBD dimer-containing antibody drug conjugate targeting CD19-expressing malignancies. Blood 2018, 131, 1094–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caimi, P.F.; Ai, W.; Alderuccio, J.P.; Ardeshna, K.M.; Hamadani, M.; Hess, B.; Kahl, B.S.; Radford, J.; Solh, M.; Stathis, A.; et al. Loncastuximab tesirine in relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (LOTIS-2): A multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 790–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeks, E.D. Polatuzumab vedotin: First global approval. Drugs 2019, 79, 1467–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sehn, L.H.; Herrera, A.F.; Flowers, C.R.; Kamdar, M.K.; McMillan, A.; Hertzberg, M.; Assouline, S.; Kim, T.M.; Kim, W.S.; Ozcan, M.; et al. Polatuzumab vedotin in relapsed or refractory diffuse large b-cell lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehn, L.H.; Hertzberg, M.; Opat, S.S.; Herrera, A.F.; Assouline, S.; Flowers, C.R.; Kim, T.M.; McMillan, A.K.; Ozcan, M.; Safar, V.; et al. Polatuzumab vedotin plus bendamustine and rituximab in relapsed/refractory DLBCL: Survival update and new extension cohort data. Blood Adv. 2022, 6, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, K.; Takahashi, H.; Nakagawa, M.; Hamada, T.; Uchino, Y.; Iizuka, K.; Ohtake, S.; Iriyama, N.; Hatta, Y.; Nakamura, H. Ideal dose intensity of R-CHOP in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Expert Rev. Anticancer. Ther. 2022, 22, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jardin, F.; Tilly, H. Chemotherapy-free treatment in unfit patients aged 75 years and older with DLBCL: Toward a new paradigm? Lancet Health Longev. 2022, 3, e453–e454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcari, A.; Cavallo, F.; Puccini, B.; Vallisa, D. New treatment options in elderly patients with Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1214026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.-P.; Shi, Z.-Y.; Qian, Y.; Cheng, S.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, L.; Li, J.-F.; Fang, H.; Huang, H.-Y.; Yi, H.-M.; et al. Ibrutinib, rituximab, and lenalidomide in unfit or frail patients aged 75 years or older with de novo diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A phase 2, single-arm study. Lancet Health Longev. 2022, 3, e481–e490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickinson, M.J.; Carlo-Stella, C.; Morschhauser, F.; Bachy, E.; Corradini, P.; Iacoboni, G.; Khan, C.; Wróbel, T.; Offner, F.; Trněný, M.; et al. Glofitamab for relapsed or refractory diffuse large b-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 2220–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thieblemont, C.; Phillips, T.; Ghesquieres, H.; Cheah, C.Y.; Roost Clausen, M.; Cunningham, D.; Do, Y.R.; Feldman, T.; Gasiorowski, R.; Jurczak, W.; et al. Epcoritamab, a novel, subcutaneous CD3xCD20 bispecific T-cell-engaging antibody, in relapsed or refractory large b-cell lymphoma: Dose expansion in a phase I/II trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 2238–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budde, L.E.; Assouline, S.; Sehn, L.H.; Schuster, S.J.; Yoon, S.-S.; Yoon, D.H.; Matasar, M.J.; Bosch, F.; Kim, W.S.; Nastoupil, L.J.; et al. Single-agent mosunetuzumab shows durable complete responses in patients with relapsed or refractory b-cell lymphomas: Phase I dose-escalation study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, W.-S.; Kim, T.M.; Cho, S.-G.; Jarque, I.; Iskierka-Jazdzewska, E.; Limei Poon, M.; Prince, H.M.; Oh, S.Y.; Lim, F.; Carpio, C.; et al. Odronextamab in patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) diffuse large b-cell lymphoma (DLBCL): Results from a prespecified analysis of the pivotal phase II study ELM-2. Blood 2022, 140, 1070–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, F.L.; Miklos, D.B.; Jacobson, C.A.; Perales, M.-A.; Kersten, M.-J.; Oluwole, O.O.; Ghobadi, A.; Rapoport, A.P.; McGuirk, J.; Pagel, J.M.; et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel as second-line therapy for large b-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 640–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.S.; Solomon, S.R.; Arnason, J.; Johnston, P.B.; Glass, B.; Bachanova, V.; Ibrahimi, S.; Mielke, S.; Mutsaers, P.; Hernandez-Ilizaliturri, F.; et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel as second-line therapy for large B-cell lymphoma: Primary analysis of the phase 3 TRANSFORM study. Blood 2023, 141, 1675–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, M.R.; Dickinson, M.; Purtill, D.; Barba, P.; Santoro, A.; Hamad, N.; Kato, K.; Sureda, A.; Greil, R.; Thieblemont, C.; et al. Second-line tisagenlecleucel or standard care in aggressive b-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucci, A.; Ferrari, S.; Bottelli, C.; Borlenghi, E.; Drera, M.; Rossi, G. A comprehensive geriatric assessment is more effective than clinical judgment to identify elderly diffuse large cell lymphoma patients who benefit from aggressive therapy. Cancer 2009, 115, 4547–4553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohile, S.G.; Dale, W.; Somerfield, M.R.; Schonberg, M.A.; Boyd, C.M.; Burhenn, P.S.; Canin, B.; Cohen, H.J.; Holmes, H.M.; Hopkins, J.O.; et al. Practical Assessment and Management of Vulnerabilities in Older Patients Receiving Chemotherapy: ASCO Guideline for Geriatric Oncology. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 2326–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.-F.; Han, H.-X.; Feng, R.; Li, J.-T.; Wang, T.; Zhang, C.-L.; Liu, H. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA): A Simple Tool for Guiding the Treatment of Older Adults with Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma in China. Oncologist 2020, 25, E1202–E1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buske, C.; Hutchings, M.; Ladetto, M.; Goede, V.; Mey, U.; Soubeyran, P.; Spina, M.; Stauder, R.; Trneny, M.; Wedding, U.; et al. ESMO consensus conference on malignant lymphoma: General perspectives and recommendations for the clinical management of the elderly patient with malignant lymphoma. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 544–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merli, F.; Luminari, S.; Tucci, A.; Arcari, A.; Rigacci, L.; Hawkes, E.; Chiattone, C.S.; Cavallo, F.; Cabras, G.; Alvarez, I.; et al. Simplified geriatric assessment in older patients with diffuse large b-cell lymphoma: The prospective elderly project of the fondazione italiana linfomi. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 1214–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northend, M.; Wilson, W.; Osborne, W.; Fox, C.P.; Davies, A.J.; El-Sharkawi, D.; Phillips, E.H.; Sim, H.W.; Sadullah, S.; Shah, N.; et al. Results of a United Kingdom real-world study of polatuzumab vedotin, bendamustine, and rituximab for relapsed/refractory DLBCL. Blood Adv. 2022, 6, 2920–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qualls, D.; Buege, M.J.; Dao, P.; Caimi, P.F.; Rutherford, S.C.; Wehmeyer, G.; Romancik, J.T.; Leslie, L.A.; Merrill, M.H.; Crombie, J.L.; et al. Tafasitamab and lenalidomide in relapsed/refractory large b cell lymphoma (R/R LBCL): Real world outcomes in a multicenter retrospective study. Blood 2022, 140, 787–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, S.; Matsushima, T.; Minami, M.; Kadowaki, M.; Takase, K.; Iwasaki, H. Clinical impact of comprehensive geriatric assessment in patients aged 80 years and older with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma receiving rituximab-mini-CHOP: A single-institute retrospective study. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2022, 13, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawton, M.P.; Brody, E.M. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 1969, 9, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Tapia, C.; Paillaud, E.; Liuu, E.; Tournigand, C.; Ibrahim, R.; Fossey-Diaz, V.; Culine, S.; Canoui-Poitrine, F.; Audureau, E.; Caillet, P.; et al. Prognostic value of the G8 and modified-G8 screening tools for multidimensional health problems in older patients with cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2017, 83, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hans, C.P.; Weisenburger, D.D.; Greiner, T.C.; Gascoyne, R.D.; Delabie, J.; Ott, G.; Müller-Hermelink, H.K.; Campo, E.; Braziel, R.M.; Jaffe, E.S.; et al. Confirmation of the molecular classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood 2004, 103, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bento, L.; Díaz-López, A.; Barranco, G.; Martín-Moreno, A.M.; Baile, M.; Martín, A.; Sancho, J.M.; García, O.; Rodríguez, M.; Sánchez-Pina, J.M.; et al. New prognosis score including absolute lymphocyte/monocyte ratio, red blood cell distribution width and beta-2 microglobulin in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP: Spanish Lymphoma Group Experience (GELTAMO). Br. J. Haematol. 2020, 188, 888–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohloch, K.; Ziepert, M.; Truemper, L.; Buske, C.; Held, G.; Poeschel, V.; Chapuy, B.; Altmann, B. Low serum albumin is an independent risk factor in elderly patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma: Results from prospective trials of the German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Study Group. eJHaem 2020, 1, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribi, K.; Rondeau, S.; Hitz, F.; Mey, U.; Enoiu, M.; Pabst, T.; Stathis, A.; Fischer, N.; Clough-Gorr, K.M. Cancer-specific geriatric assessment and quality of life: Important factors in caring for older patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 25, 2833–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Go, S.-I.; Park, S.; Kang, M.H.; Kim, H.-G.; Kim, H.R.; Lee, G.-W. Clinical impact of prognostic nutritional index in diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Ann. Hematol. 2019, 98, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pergolotti, M.; Deal, A.M.; Williams, G.R.; Bryant, A.L.; Bensen, J.T.; Muss, H.B.; Reeve, B.B. Activities, function, and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of older adults with cancer. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2017, 8, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizutani, T.; Nakamura, K.; Fukuda, H.; Ogawa, A.; Hamaguchi, T.; Nagashima, F.; Geriatric Study Committee/Japan Clinical Oncology Group. Geriatric Research Policy: Japan Clinical Oncology Group (JCOG) policy. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 49, 901–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamasaki, S. Feasibility of Quality of Life Assessment in Patients with Lymphoma Aged ≥80 Years Receiving Reduced-Intensity Chemotherapy: A Single-Institute Study. Hematol. Rep. 2023, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hormigo-Sanchez, A.I.; Lopez-Garcia, A.; Mahillo-Fernandez, I.; Askari, E.; Morillo, D.; Perez-Saez, M.A.; Riesco, M.; Urrutia, C.; Martinez-Peromingo, F.J.; Cordoba, R.; et al. Frailty assessment to individualize treatment in older patients with lymphoma. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2023, 14, 1393–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westin, J.; Davis, R.E.; Feng, L.; Hagemeister, F.; Steiner, R.; Lee, H.J.; Fayad, L.; Nastoupil, L.; Ahmed, S.; Rodriguez, A.; et al. Smart start: Rituximab, lenalidomide, and ibrutinib in patients with newly diagnosed large b-cell lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszewski, A.J.; Avigdor, A.; Babu, S.; Levi, I.; Eradat, H.; Abadi, U.; Holmes, H.; McKinney, M.; Woszczyk, D.; Giannopoulos, K.; et al. Mosunetuzumab monotherapy continues to demonstrate promising efficacy and durable complete responses in elderly/unfit patients with previously untreated diffuse large b-cell lymphoma. Blood 2022, 140, 1778–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Therapy Type | Age | Development Status | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| R-CHOP | 60–80 years | Phase 3 trial | Coiffier et al., 2002 [1] |

| R-mini-CHOP | ≥80 years | Phase 2 trial | Peyrade et al., 2011 [28] Peyrade et al., 2017 [29] |

| Pola-R-CHP | <80 years | Phase 3 trial | Tilly et al., 2022 [5] |

| Pola-R-mini-CHP | ≥80 years or frail patients aged ≥75 years | Phase 3 trial, ongoing | ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04332822 |

| Therapy Type | Example(s) | Development Status | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BTK inhibitor | Ibrutinib | Phase 2 trial | Xu et al., 2022 [63] |

| Tafa-Len | Tafa-Len | Phase 2 trial | Salles et al., 2020 [53] Duell et al., 2021 [54] |

| CD19 antibody–drug conjugate | Lonca | Phase 2 trial | Caimi et al., 2021 [55] |

| Bispecific antibody | Glofitamab Epcoritamab | Phase 2 trial | Dickinson et al., 2022 [64] Thieblemont et al., 2023 [65] |

| CAR T-cells | Axi-cel Liso-cel Tisa-cel | Phase 3 trial | Cocke et al., 2022 [68] Abramson et al., 2022 [69] Bishop et al., 2022 [70] |

| Assessment Tool | Key Parameters | Benefits | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive geriatric assessment | ADL, IADL, CCI, CIRS-G | Recommended by ASCO (Mohile et al., 2018 [72]) | Complexity, time (Moccia and Thieblemont, 2018 [17]) |

| Simplified geriatric assessment (Merli et al., 2021 [75]) | ADL, IADL, age, (≥80 years), CIRS-G, IPI, hemoglobin | OS, CR rate (Bai et al., 2020 [73]) | Complexity |

| IADL (Lawton and Brody, 1969 [79]) | IADL | Predicts OS with R-mini-CHOP therapy (Yamasaki et al., 2022 [78]) | Reproducibility |

| G8 screening test (Martinez-Tapia et al., 2017 [80]) | G8 | OS, treatment toxicity | Reproducibility |

| Age, comorbidities, albumin index, and IADL (Hohloch et al., 2020 [83]) | Age, CCI, albumin (≤3.5 g/dL) | OS, mean chemotherapy dose, treatment toxicity, treatment-related toxicity | Reproducibility |

| Vulnerable elders survey-13 (Ribi et al., 2015 [84]) | Vulnerable elders survey-13 | OS, response rate | Reproducibility |

| Prognostic nutritional index (Go et al., 2019 [85]) | Prognostic nutritional index | OS | Reproducibility |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yamasaki, S. Appropriate Treatment Intensity for Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma in the Older Population: A Review of the Literature. Hematol. Rep. 2024, 16, 317-330. https://doi.org/10.3390/hematolrep16020032

Yamasaki S. Appropriate Treatment Intensity for Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma in the Older Population: A Review of the Literature. Hematology Reports. 2024; 16(2):317-330. https://doi.org/10.3390/hematolrep16020032

Chicago/Turabian StyleYamasaki, Satoshi. 2024. "Appropriate Treatment Intensity for Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma in the Older Population: A Review of the Literature" Hematology Reports 16, no. 2: 317-330. https://doi.org/10.3390/hematolrep16020032

APA StyleYamasaki, S. (2024). Appropriate Treatment Intensity for Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma in the Older Population: A Review of the Literature. Hematology Reports, 16(2), 317-330. https://doi.org/10.3390/hematolrep16020032