Pilot Study on the Evaluation of the Diet of a Mexican Population of Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects and Study Design

2.2. Food Intake

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

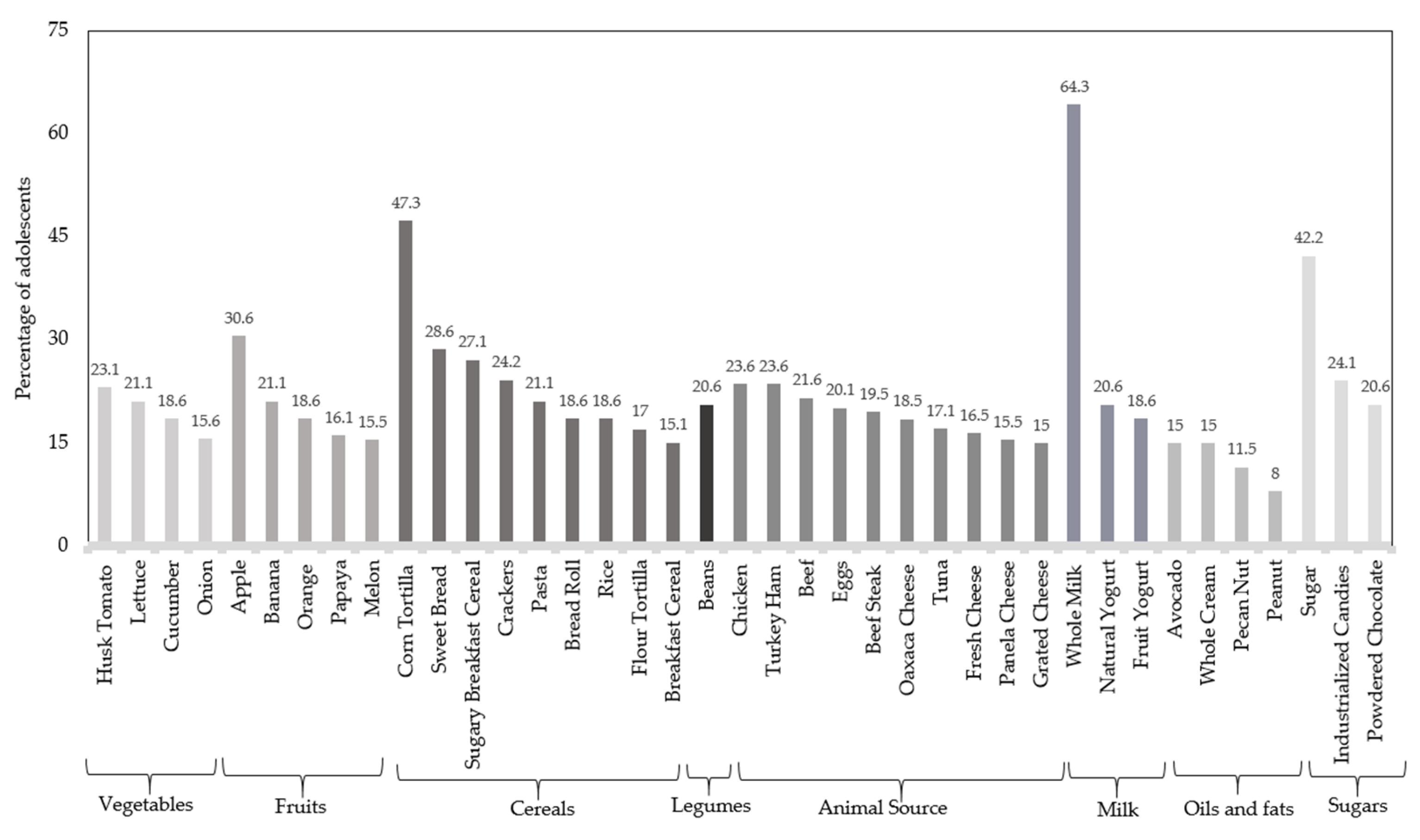

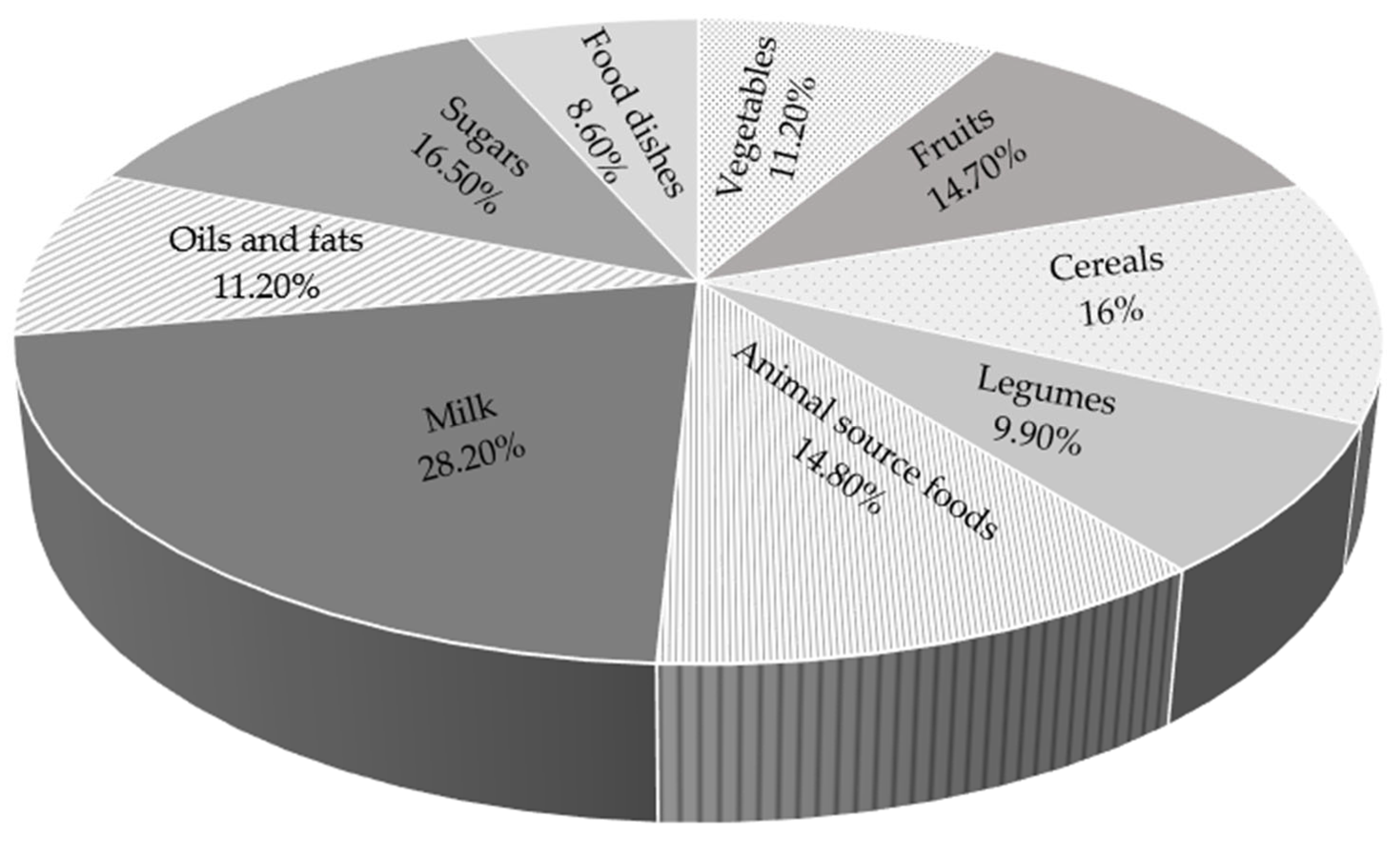

Food Intake

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire Was Carried out Once and Included Consumption Frequencies

| Name: | Registration number: | Date: | |||

| Age: | Grade: | Group: | Height: | Weight: | %Fat: |

| Address: | |||||

| What is your parents’ marital status? ( ) married ( ) divorced ( ) widower/widow ( ) Unmarried ( ) common-law relationship | |||||

| What is your mother´s occupation and highest level of education? | |||||

| Who are you living with? ( ) Parents ( ) Alone ( ) Couple ( ) Friends ( ) Other | |||||

| How many siblings are there incluiding you? | |||||

| Are you the oldest, middle, or youngest sibling? | |||||

| What is your socioeconomic status? ( ) Upper class ( ) Upper middle class ( ) Middle class ( )Upper-middle class ( ) Working poor ( ) Poor | |||||

| What is your montly family income? | |||||

| Food | Portions | Frequency | |||||||

| 4–5/day | 2–3/day | 1/day | 5–6/week | 2–4/week | 1/week | 2–5/Fortnight | Never | ||

| Avocado | Half a piece | ||||||||

| Rise | 1 cup | ||||||||

| Oats or Granola | 3 tablespoons | ||||||||

| Pasta soup | 1 cup | ||||||||

| Spaguetti | 1 cup | ||||||||

| Strawberries | 1 cup | ||||||||

| Cream | 1 tablespoon | ||||||||

| Butter | 1 teaspoon | ||||||||

| Peach | 1 piece | ||||||||

| Guava | 1 piece | ||||||||

| Oranje | 1 piece | ||||||||

| Cookies | 2 pieces | ||||||||

| Sweet bread | 1 piece | ||||||||

| Radishes | 1 cup | ||||||||

| Cake | 1 slice | ||||||||

| Tuna | 1 can | ||||||||

| Beef steak | 1 piece (90 grams) | ||||||||

| Beans | ½ cup | ||||||||

| Milk | 1 cup | ||||||||

| Pumpkin | ½ cup | ||||||||

| Onion | ½ cup | ||||||||

| Cabbage | 1 cup | ||||||||

| Corn | 1 cup | ||||||||

| Plain yogurt | 1 cup | ||||||||

| Crackers | 4 pieces | ||||||||

| Pizza | 1 slice | ||||||||

| Jam | 1 tablespoon | ||||||||

| Mandarin | 1 piece | ||||||||

| Mango | 1 piece | ||||||||

| French fries | 1 cup | ||||||||

| Chips | 1 bag (45 grams) | ||||||||

| Tamal | 1 piece | ||||||||

| Lentils | ½ cup | ||||||||

| Ice cream | 1 scoop | ||||||||

| Chayote | ½ cup | ||||||||

| Sugar-free cereal | ½ cup | ||||||||

| Sweetened cereal | ½ cup | ||||||||

| Hot cake | 1 piece | ||||||||

| Apple | 1 piece | ||||||||

| Peanuts | 1 small bag | ||||||||

| Fried snacks | 1 small bag | ||||||||

| Walnut | 1 tablespoon | ||||||||

| Melon | 1 cup | ||||||||

| Papaya | 1 cup | ||||||||

| Turkey ham | 1 slice | ||||||||

| Chicken | 1 piece | ||||||||

| Pea | ½ cup | ||||||||

| Candy | 1 piece | ||||||||

| Jicama | 1 cup | ||||||||

| Popcorn | 3 cups | ||||||||

| Bolillo or Telera | 1 piece | ||||||||

| Bread | 1 slice | ||||||||

| Chorizo | 1 tablespoon | ||||||||

| Fish | 1 piece | ||||||||

| Barbacoa | 1 serving | ||||||||

| Lettuce | 1 cup | ||||||||

| Tomato | 1 piece | ||||||||

| Nopal | 1 cup/1 piece | ||||||||

| Potato | 1 piece | ||||||||

| Tortilla | 1 piece | ||||||||

| Flour tortilla | 1 piece | ||||||||

| Shredded cheese | 1 tablespoon | ||||||||

| Ham | 1 slice | ||||||||

| Pork | 1 piece (70 grams) | ||||||||

| Purslane | ½ cup | ||||||||

| Sugar | 1 teaspoon | ||||||||

| Caramel sauce | 1 teaspoon | ||||||||

| Cocoa powder | 1 tablespoon | ||||||||

| Pear | 1 piece | ||||||||

| Pineapple | 1 cup | ||||||||

| Banana | 1 serving (85 grams) | ||||||||

| Cheese | 1 serving (30 grams) | ||||||||

| Panela cheese | 1 serving (30 grams) | ||||||||

| Carrot | ½ cup | ||||||||

| Husk tomato (sauce) | ½ cup | ||||||||

| Cucumber | 1 cup | ||||||||

| Hamburger | 1 piece | ||||||||

| Egg | 1 piece | ||||||||

| Paste | 1 piece | ||||||||

| Green beans | 1 cup | ||||||||

| Melting cheese | 1 serving (30 grams) | ||||||||

| Grapes | 18 pieces | ||||||||

| Chickpea | ½ cup | ||||||||

| Mole | 1 tablespoon | ||||||||

| Prickly pear | 1 piece | ||||||||

| Juice | 500 mililiters | ||||||||

| Pork cracklings | 1 serving | ||||||||

| Watermelon | 1 cup | ||||||||

| Roast chicken | 1 piece | ||||||||

| Cheddar cheese | 1 slice | ||||||||

| Sweetened milk | 1 cup | ||||||||

| Fruit yogurt | 1 cup | ||||||||

| Sausage | 1 piece | ||||||||

| Mayonnaise | 1 teaspoon | ||||||||

| Soda | 1 glass | ||||||||

| Ketchup | 1 tablespoon | ||||||||

| Chocolate | 1 piece | ||||||||

| Chilaquiles | 1 plate | ||||||||

- Interviewer´s name:_________________________________________________________

Appendix B. Questionnaire to Indicate Their Most Frequent Food Preparation Methods

| Food | Preparation | ||||||

| Raw | Cooked | Fried | Roasted/Grilled | Baked | Toasted | I don´t consume | |

| Tuna | |||||||

| Barbacoa | |||||||

| Cheese | |||||||

| String cheese | |||||||

| Manchego cheese | |||||||

| Beef | |||||||

| Beans | |||||||

| Lentils | |||||||

| Chicken | |||||||

| Bolillo/Telera | |||||||

| Bread | |||||||

| Chorizo | |||||||

| Fish | |||||||

| Tortilla | |||||||

| Pork | |||||||

| Cheese | |||||||

| Sausage | |||||||

| Egg | |||||||

| Milk | |||||||

| Butter | |||||||

| Nuts/Peanuts/Almonds | |||||||

References

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Desarrollo en la Adolescencia. OMS. 2015. Available online: https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/adolescence/dev/es/ (accessed on 9 August 2019).

- Nicholaus, C.; Martin, H.; Kassim, N.; Matemu, A.; Kimiywe, J. Dietary practices, nutrient adequacy, and nutrition status among adolescents in boarding high schools in the kilimanjaro region, Tanzania. J. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 2020, 3592813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, M.R.; Barrientos-Gutiérrez, T.; Cuevas-Nasu, L.; Bautista-Arredondo, S.; Colchero, M.A.; Gaona-Pineda, E.B.; Martínez-Barnetche, J.; Alpuche-Aranda, C.M.; Gómez-Acosta, L.M.; Mendoza-Alvarado, L.R.; et al. Metodología de la Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición 2021. Salud Publica De Mex. 2021, 63, 813–818. Available online: https://www.saludpublica.mx/index.php/spm/article/view/13348 (accessed on 20 July 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barriguete, J.; Vega, S.; Radilla, C.; Barquera, S.; Hernández, L.; Rojo-Moreno, L. Hábitos alimentarios, actividad física y estilos de vida en adolescentes escolarizados de la Ciudad de México y del Estado de Michoacán. Rev. Española Nutr. Comunitaria 2017, 23, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda-Sánchez, O.; Rocha-Díaz, J.; Ramos-Aispuro, M. Evaluación de los hábitos alimenticios y estado nutricional en adolescentes de Sonora, México. Arch. En Med. Fam. 2008, 10, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública, Secretaría de Salud. Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición 2018. Available online: https://ensanut.insp.mx/encuestas/ensanut2018/doctos/informes/ensanut_2018_presentacion_resultados.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Pérez-Islas, J.E. Reproducibilidad y Validez de un Cuestionario Semicuantitativo de Frecuencia de Consumo de Alimentos para Adolescentes. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo, Pachuca de Soto, México, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, A.L.; Palacios, B.C.; Castro ABy Flores, I.G. Sistema Mexicano de Alimentos Equivalentes, 4th ed.; Fomento de Nutrición y Salud: Ogali, Mexico, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dapcich, V.; Castell, G.S.; Ribas, L.; Pérez, C.; Aranceta, J.; Serra, J. Guía de Alimentación Saludable; Sociedad Española de Nutrición Comunitaria: Madrid, Spain, 2004; pp. 11–97. [Google Scholar]

- NOM-043-SSA2-2012; Servicios Básicos de Salud. Promoción y Educación para la Salud en Materia Alimentaria. Criterios para Brindar Orientación. Secretaría de Salud: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2012.

- Gaona-Pineda, E.B.; Rodríguez-Ramírez, S.; Medina-Zacarías, M.C.; Valenzuela-Bravo, D.G.; Martinez-Tapia, B.; Arango-Angarita, A. Consumidores de grupos de alimentos en población mexicana. Ensanut Continua 2020–2022. Salud Pública México 2023, 65, s248–s258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo-Ojeda, G.; Bernal-Orozco, M.; López-Uriarte, P.; Hunot, C.; Vizmanos, B.; Rovillé-Sausse, F. Hábitos alimentarios en adolescentes de la Zona Urbana de Guadalajara, México. Antropo 2008, 16, 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Secretaria de Educación Publica (SEP). Preparación, Distribución y el Expendio de los Alimentos y Bebidas Preparados, Procesados y a Granel, Así Como el Fomento de los Estilos de vida Saludables en Alimentación, Dentro de Toda Escuela del Sistema Educativo Nacional; SEP: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cámara de Diputados del, H. Congreso de la Unión. Ley del Impuesto Especial Sobre Producción y Servicios; Cámara de Diputados del H. Congreso de la Unión: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, F. ; Torres A, Hidratación. Fundamentos en las Diferentes Etapas de la Vida; Editorial Alfil: San Rafael, Mexico, 2024; pp. 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Urquiaga, I.; Echeverría, G.; Dussaillant, C.; Rigotti, A. Origen, componentes y posibles mecanismos de acción de la dieta mediterránea. Rev. Med. Chile 2017, 145, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saulais, L.; Corcuff, R.; Boonefaes, E. Natural and healthy? Consumers knowledge, understanding and preferences regarding naturalness and healthiness of processed foods. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2023, 31, 100662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Varela, M.; Ruso, C.; Micó, A.; Llopis, A. Valoración del patrón alimentario en adolescentes españoles en zona mediterránea y atlántica: Un estudio piloto. Rev. Esp. Nutr. Comunitaria 2014, 20, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarenga, B.; Determinación del Patrón de Consumo de Alimentos y Estado Nutricional en Jóvenes de 13 a 17 Años de Edad del Instituto San Antonio de Oriente (El Jicarito), San Antonio de Oriente, Francisco Morazán, Honduras. Escuela Agrícola Panamericana, Zamora Honduras. 2015. Available online: https://bdigital.zamorano.edu/bitstream/11036/4534/1/AGI-2015-005.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Ministerio de Salud. Atención Integral de la Salud de Adolescentes y Jóvenes. Encuesta Mundial de Salud Escolar; Ministerio de Salud: San Salvador, El Salvador, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Montagnese, C.; Santarpia, L.; Iavarone, F.; Strangio, F.; Caldara, A.R.; Silvestri, E.; Pasanisi, F. North and South American countries food-based dietary guidelines: A comparison. Nutrition 2017, 42, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marugán, J.; Monasterio, L.; Pavón, M. Alimentación en el Adolescente; Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid: Madrid, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Vargas, L.; Vermandere, H.; Bautista-Arredondo, S.; Colchero, M.A. The role of social determinants on unhealthy eating habits in an urban area in Mexico: A qualitative study in low-income mothers with a young child at home. Appetite 2022, 169, 105852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Villares, J.; Galiano-Segovia, M. Alimentación del niño preescolar, escolar y del adolescente. Pediatría Integral 2015, 24, 268–276. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, M.; García, A.; Salinero, J.; Pérez, B.; Sánchez, J.; Gracia, R. Calidad de la dieta y su relación con el IMC y el sexo en adolescentes. Nutr. Clin. Die. Hosp. 2012, 32, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera-Rojas, M.Á. Comida chatarra: entre la gobernanza regulatoria y la simulación. Estudios sociales. Rev. Aliment. Contemp. Desarro. Reg. 2021, 31, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOM-051-SCFI/SSA1-2010; Especificaciones Generales de Etiquetado para Alimentos y Bebidas no Alcohólicas Preenvasados—Información Comercial y Sanitaria. [Norma Oficial Mexicana]. Secretaría de Economía y Secretaría de Salud: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2010.

- Figueiredo, N.; Paula, N.M.D. Desafíos en las políticas públicas de seguridad alimentaria en México: Un estudio del programa desayunos escolares. Estud. Soc. Rev. Aliment. Contemp. Desarro. Reg. 2022, 31, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guibrunet, L.; Ortega-Avila, A.G.; Arnés, E.; Mora Ardila, F. Socioeconomic, demographic and geographic determinants of food consumption in Mexico. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perng, W.; Fernandez, C.; Peterson, K.; Zhang, Z.; Cantoral, A.; Sanchez, B. Dietary patterns exhibit sex-specific associations with adiposity and metabolic risk in a cross-sectional study in urban Mexican adolescents. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 1977–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Viera, M.E.; van den Berg, M.; Donovan, J.; Perez-Luna, M.E.; Ospina-Rojas, D.; Handgraaf, M. Demand for healthier and higher-priced processed foods in low-income communities: Experimental evidence from Mexico City. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 95, 104362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Fomento del Consumo Mundial de Frutas y Verduras. 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet (accessed on 7 April 2018).

- Yang, F.; Wolk, A.; Håkansson, N.; Pedersen, N.; Wirdefeldt, K. Dietary antioxidants and risk of Parkinson’s disease in two population-based cohorts. Mov. Disord. 2017, 32, 1631–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras, S. Capacidad Antioxidante de la Dieta Española; Facultad de Farmacia, Universidad Complutense: Madrid, España, 2015; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14352/66302 (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Jain, A.; Mehra, N.; Swarnakar, N. Role of Antioxidants for the Treatment of Cardiovascular Diseases: Challenges and Opportunities. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2015, 21, 4441–4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siti, H.N.; Kamisah, Y.; Kamsiah, J. The role of oxidative stress, antioxidants and vascular inflammation in cardiovascular disease (a review). Vasc. Pharmacol. 2015, 71, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, M. Epidemiology of Noncommunicable Diseases. In Textbook of Clinical Epidemiology: For Medical Students; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceves-Martins, M.; López-Cruz, L.; García-Botello, M.; Godina-Flores, N.L.; Gutierrez-Gómez, Y.Y.; Moreno-García, C.F. Cultural factors related to childhood and adolescent obesity in Mexico: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Obes. Rev. 2022, 23, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augimeri, G.; Galluccio, A.; Caparello, G.; Avolio, E.; La Russa, D.; De Rose, D.; Bonofiglio, D. Potential antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of serum from healthy adolescents with optimal Mediterranean diet adherence: Findings from DIMENU cross-sectional study. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Food | G Fresh Matter of Edible Portion/Day/Person * | Equivalent Foods ** | Number of Total Recommended Servings *** |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetables | |||

| Cucumber | 62.52 ± 94.01 | 0.60 | |

| Husk Tomato | 75.36 ± 122.04 | 0.88 | |

| Lettuce | 35.12 ± 47.18 | 0.26 | |

| Onion | 40.28 ± 66.37 | 0.69 | |

| Tomato | 53.65 ± 84.01 | 0.47 | |

| Total | 269.93 | 2.90 | 4 |

| Fruits | |||

| Apple | 118.75 ± 163.66 | 1.12 | |

| Banana | 74.09 ± 114.75 | 1.37 | |

| Melon | 75.26 ±126.18 | 0.42 | |

| Orange | 46.89 ± 76.59 | 0.31 | |

| Papaya | 67.60 ± 124.80 | 0.48 | |

| Total | 382.59 | 3.70 | 3 |

| Cereals | |||

| Bread Roll | 27.71 ± 41.24 | 1.38 | |

| Breakfast Cereal | 5.11 ± 9.64 | 0.27 | |

| Corn Tortilla | 41.73 ±44.86 | 1.39 | |

| Crackers | 5.29 ± 10.48 | 0.33 | |

| Flour Tortilla | 21.01 ± 35.36 | 0.75 | |

| Pasta | 80.60 ± 105.81 | 1.34 | |

| Rice | 38.64 ± 48.79 | 0.82 | |

| Sugary Breakfast Cereal | 8.48 ± 11.67 | 0.65 | |

| Sweet Bread | 34.60 ± 48.20 | 1.65 | |

| Total | 263.17 | 8.58 | 10 |

| Legumes | |||

| Beans | 73.17 ± 96.79 | 0.85 | 2 |

| Oils and fats | |||

| Avocado | 19.26± 32.00 | 0.62 | |

| Japanese Peanut | 7.43 ± 15.09 | 0.53 | |

| Natural Peanut | 7.43 ± 15.09 | 0.62 | |

| Pecan Nut | 2.35 ± 4.57 | 0.26 | |

| Soy Oil | 27.78 | 5.56 | |

| Total | 64.25 | 7.59 | 5 |

| Sugars | |||

| Powdered Chocolate | 2.88 ± 4.78 | 0.29 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Escamilla-Gutiérrez, K.R.; López-García, A.; del Socorro Cruz-Cansino, N.; Ariza-Ortega, J.A.; Sandoval-Gallegos, E.M.; Ramírez-Moreno, E.; Arias-Rico, J. Pilot Study on the Evaluation of the Diet of a Mexican Population of Adolescents. Pediatr. Rep. 2025, 17, 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17040078

Escamilla-Gutiérrez KR, López-García A, del Socorro Cruz-Cansino N, Ariza-Ortega JA, Sandoval-Gallegos EM, Ramírez-Moreno E, Arias-Rico J. Pilot Study on the Evaluation of the Diet of a Mexican Population of Adolescents. Pediatric Reports. 2025; 17(4):78. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17040078

Chicago/Turabian StyleEscamilla-Gutiérrez, Karen Rubí, Alejandra López-García, Nelly del Socorro Cruz-Cansino, José Alberto Ariza-Ortega, Eli Mireya Sandoval-Gallegos, Esther Ramírez-Moreno, and José Arias-Rico. 2025. "Pilot Study on the Evaluation of the Diet of a Mexican Population of Adolescents" Pediatric Reports 17, no. 4: 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17040078

APA StyleEscamilla-Gutiérrez, K. R., López-García, A., del Socorro Cruz-Cansino, N., Ariza-Ortega, J. A., Sandoval-Gallegos, E. M., Ramírez-Moreno, E., & Arias-Rico, J. (2025). Pilot Study on the Evaluation of the Diet of a Mexican Population of Adolescents. Pediatric Reports, 17(4), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17040078