From Early Stress to Adolescent Struggles: How Maternal Parenting Stress Shapes the Trajectories of Internalizing, Externalizing, and ADHD Symptoms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Maternal Parenting Stress

2.2.2. Children’s Emotional, Behavioral and ADHD Difficulties

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptives of the Study Population

3.2. Descriptives of the Study Outcome Variables for the Total Sample and by Sex

3.3. Univariate Associations Between Maternal Parenting Stress and Internalizing, Externalizing and ADHD Symptoms at Ages 4, 6, 11, and 15 Years

3.4. Multivariate Associations Between Maternal Parenting Stress and Trajectories of Internalizing, Externalizing and ADHD Symptoms from 4 to 15 Years of Age, Mixed Model Analyses

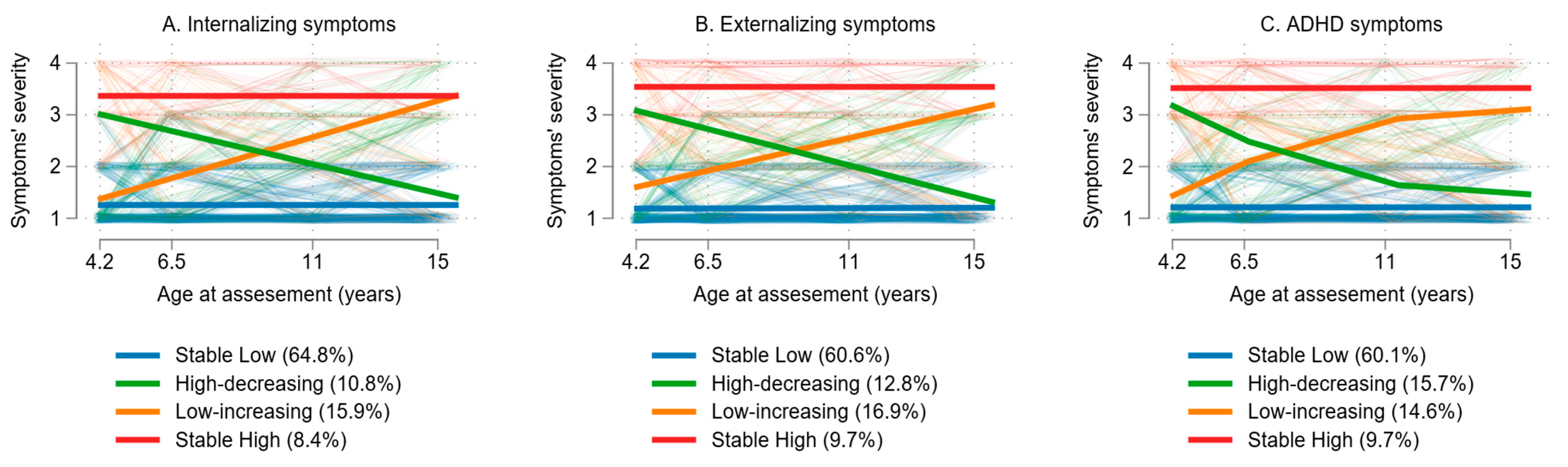

3.5. Multivariate Associations Between Maternal Parenting Stress and Trajectories of Internalizing, Externalizing and ADHD Symptoms from 4 to 15 Years of Age, Group-Based Trajectory Modeling

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADHD | Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder |

| ADHDT | Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Test |

| APP | Average Posterior Probabilities |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| CBCL | Child Behavior Checklist |

| CIs | Confidence intervals |

| GBTM | Group-Based Trajectory Modeling |

| CPRS-R:S | Conners’ Parent Rating Scale-Revised: Short Form |

| OCC | Odds of Correct Classification |

| PSS | Parental Stress Scale |

| RRRs | relative risk ratios |

| SDQ | Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire |

References

- Clayborne, Z.M.; Varin, M.; Colman, I. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: Adolescent Depression and Long-Term Psychosocial Outcomes. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 58, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korhonen, M.; Luoma, I.; Salmelin, R.; Siirtola, A.; Puura, K. The Trajectories of Internalizing and Externalizing Problems from Early Childhood to Adolescence and Young Adult Outcome. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2018, 2, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bor, W.; Dean, A.J.; Najman, J.; Hayatbakhsh, R. Are Child and Adolescent Mental Health Problems Increasing in the 21st Century? A Systematic Review. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2014, 48, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klasen, F.; Otto, C.; Kriston, L.; Patalay, P.; Schlack, R.; Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Group, B.S. Risk and Protective Factors for the Development of Depressive Symptoms in Children and Adolescents: Results of the Longitudinal BELLA Study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2015, 24, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achenbach, T.M.; Edelbrock, C.S. The Classification of Child Psychopathology: A Review and Analysis of Empirical Efforts. Psychol. Bull. 1978, 85, 1275–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Lewis, G. Childhood Internalizing Behaviour: Analysis and Implications. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2011, 18, 884–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J. Childhood Externalizing Behavior: Theory and Implications. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2004, 17, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayal, K.; Prasad, V.; Daley, D.; Ford, T.; Coghill, D. ADHD in Children and Young People: Prevalence, Care Pathways, and Service Provision. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polanczyk, G.V.; Salum, G.A.; Sugaya, L.S.; Caye, A.; Rohde, L.A. Annual Research Review: A Meta-Analysis of the Worldwide Prevalence of Mental Disorders in Children and Adolescents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2015, 56, 345–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bibou-Nakou, I.; Markos, A.; Padeliadu, S.; Chatzilampou, P.; Ververidou, S. Multi-Informant Evaluation of Students’ Psychosocial Status through SDQ in a National Greek Sample. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 96, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, R.R. Parenting Stress Index Manual, 3rd ed.; Psychological Assessment Resources: Odessa, FL, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Abidin, R.R. Parenting Stress Index; Psychological Assessment Resources: Odessa, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, R.A. Development in the First Years of Life. Future Child 2001, 11, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, C.A.; Haan, M.; Thomas, K.M. Neural Bases of Cognitive Development. In Handbook of Child Psychology; Siegler, R., Kuhn, D., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; Volume 2, pp. 3–57. [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff, J.P.; Phillips, D.A. From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Conger, K.J.; Rueter, M.A.; Conger, R.D. The Role of Economic Pressure in the Lives of Parents and Their Adolescents: The Family Stress Model. In Negotiating Adolescence in Times of Social Change; Crockett, L.J., Silbereisen, R.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; pp. 201–223. [Google Scholar]

- Guajardo, N.R.; Snyder, G.; Peterson, R. Relationships among Parenting Practices, Parental Stress, Child Behavior, and Children’s Social-Cognitive Development. Infant Child Dev. 2009, 18, 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neece, C.L.; Green, S.A.; Baker, B.L. Parenting Stress and Child Behavior Problems: A Transactional Relationship across Time. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 117, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chardon, M.L.; Stromberg, S.E.; Lawless, C.; Fedele, D.A.; Carmody, J.K.; Dumont-Driscoll, M.C.; Janicke, D.M. The Role of Child and Adolescent Adjustment Problems and Sleep Disturbance in Parent Psychological Distress. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2018, 47, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiteside-Mansell, L.; Ayoub, C.; McKelvey, L.; Faldowski, R.A.; Hart, A.; Shears, J. Parenting Stress of Low-Income Parents of Toddlers and Preschoolers: Psychometric Properties of a Short Form of the Parenting Stress Index. Parent. Sci. Pract. 2007, 7, 26–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haskett, M.E.; Ahern, L.S.; Ward, C.S.; Allaire, J.C. Factor Structure and Validity of the Parenting Stress Index-Short Form. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2006, 35, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubois-Comtois, K.; Moss, E.; Cyr, C.; Pascuzzo, K. Behavior Problems in Middle Childhood: The Predictive Role of Maternal Distress, Child Attachment, and Mother-Child Interactions. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2013, 41, 1311–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benzies, K.M.; Harrison, M.J.; Magill-Evans, J. Parenting Stress, Marital Quality, and Child Behavior Problems at Age 7 Years. Public Health Nurs. 2004, 21, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carapito, E.; Ribeiro, M.T.; Pereira, A.I.; Roberto, M.S. Parenting Stress and Preschoolers’ Socio-Emotional Adjustment: The Mediating Role of Parenting Styles in Parent–Child Dyads. J. Fam. Stud. 2020, 26, 594–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, C.M. Association between Independent Reports of Maternal Parenting Stress and Children’s Internalizing Symptomatology. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2011, 20, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, W.; Moor, M.H.M.; Oosterman, M.; Huizink, A.C.; Matvienko-Sikar, K. Longitudinal Relations between Parenting Stress and Child Internalizing and Externalizing Behaviors: Testing within-Person Changes, Bidirectionality and Mediating Mechanisms. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 942363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiff, C.J.; Lengua, L.J.; Zalewski, M. Nature and Nurturing: Parenting in the Context of Child Temperament. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 14, 251–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackler, J.S.; Kelleher, R.T.; Shanahan, L.; Calkins, S.D.; Keane, S.P.; O’Brien, M. Parenting Stress, Parental Reactions, and Externalizing Behavior from Ages 4 to 10. J. Marriage Fam. 2015, 77, 388–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, L.L.; Mares, S.H.; Otten, R.; Engels, R.C.; Janssens, J.M. The Co-Development of Parenting Stress and Childhood Internalizing and Externalizing Problems. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess 2016, 38, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Maat, D.A.; Jansen, P.W.; Prinzie, P.; Keizer, R.; Franken, I.H.; Lucassen, N. Examining Longitudinal Relations between Mothers’ and Fathers’ Parenting Stress, Parenting Behaviors, and Adolescents’ Behavior Problems. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2021, 30, 771–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, N.E.; Mendez, L.; Graziano, P.A.; Bagner, D.M. Parenting Stress through the Lens of Different Clinical Groups: A Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2018, 46, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzi, L.; Leventakou, V.; Vafeiadi, M.; Koutra, K.; Roumeliotaki, T.; Chalkiadaki, G.; Karachaliou, M.; Daraki, V.; Kyriklaki, A.; Kampouri, M.; et al. Cohort profile: The mother-child cohort in Crete, Greece (Rhea Study). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 1392–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, J.O.; Jones, W.H. The Parental Stress Scale: Initial Psychometric Evidence. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 1995, 12, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelman, J.J.; Ferro, M.A. The Parental Stress Scale: Psychometric Properties in Families of Children with Chronic Health Conditions. Fam. Relat. 2018, 67, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A Research Note. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1997, 38, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bibou-Nakou, I.; Kiosseoglou, G.; Stogiannidou, A. Strengths and Difficulties of School-Aged Children in the Family and School Context. Psychol. J. Hell. Psychol. Soc. 2001, 8, 506–525. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach, T.M.; Edelbrock, C. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist; The University of Vermont: Burlington, VT, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Roussos, A.; Karantanos, G.; Richardson, C.; Hartman, C.; Karajiannis, D.; Kyprianos, S.; Lazaratou, H.; Mahaira, O.; Tassi, M.; Zoubou, V. Achenbach’s Child Behavior Checklist and Teachers’ Report Form in a Normative Sample of Greek Children 6–12 Years Old. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1999, 8, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilliam, J.E. Examiners Manual for the Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Test: A Method for Identifying Individuals with ADHD; Pro-Ed: Austin, TX, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Maniadaki, K.; Kakouros, E. Translation and Adaptation of the Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Test (ADHDT.; Giliam, 1995). In The Psychometric Instruments in Greece; Stalikas, A., Triliva., S., Roussi, P., Eds.; Ellinika Grammata: Athens, Greece, 2002; pp. 102–103. [Google Scholar]

- Conners, C.K.; Sitarenios, G.; Parker, J.D.A.; Epstein, J.N. The Revised Conners’ Parent Rating Scale (CPRS-R): Factor Structure, Reliability, and Criterion Validity. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 1998, 26, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colman, I.; Ataullahjan, A.; Naicker, K.; Lieshout, R.J. Birth Weight, Stress, and Symptoms of Depression in Adolescence: Evidence of Fetal Programming in a National Canadian Cohort. Can. J. Psychiatry 2012, 57, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naicker, K.; Wickham, M.; Colman, I. Timing of First Exposure to Maternal Depression and Adolescent Emotional Disorder in a National Canadian Cohort. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, 33422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weeks, M.; Cairney, J.; Wild, T.C.; Ploubidis, G.B.; Naicker, K.; Colman, I. Early-life Predictors of Internalizing Symptom Trajectories in Canadian Children. Depress. Anxiety 2014, 31, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagin, D.S.; Odgers, C.L. Group-Based Trajectory Modeling in Clinical Research. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 6, 109–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ram, N.; Grimm, K.J. Methods and Measures: Growth Mixture Modeling: A Method for Identifying Differences in Longitudinal Change among Unobserved Groups. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2009, 33, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, J.; Franchett, E.E.; Oliveira, C.V.; Rehmani, K.; Yousafzai, A.K. Parenting Interventions to Promote Early Child Development in the First Three Years of Life: A Global Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, 1003602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, S.C.; Bai, S. Bidirectional Associations between Parenting Stress and Child Psychopathology: The Moderating Role of Maternal Affection. Dev. Psychopathol. 2023, 1, 1810–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinelli, M.; Lionetti, F.; Setti, A.; Fasolo, M. Parenting Stress during the COVID-19 Outbreak: Socioeconomic and Environmental Risk Factors and Implications for Children Emotion Regulation. Fam. Process 2021, 60, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daundasekara, S.S.; Beauchamp, J.E.S.; Hernandez, D.C. Parenting Stress Mediates the Longitudinal Effect of Maternal Depression on Child Anxiety/Depressive Symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 295, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Lin, X.; Heath, M.A.; Zhou, Q.; Ding, W.; Qin, S. Longitudinal Linkages between Parenting Stress and Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) Symptoms among Chinese Children with ODD. J. Fam. Psychol. 2018, 32, 1078–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, D.Y. The Relation among Parenting Stress, Anger and Anger Expression in Infant’s Mothers. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. 2012, 13, 1170–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendergast, S.; MacPhee, D. Trajectories of Maternal Aggression in Early Childhood: Associations with Parenting Stress, Family Resources, and Neighborhood Cohesion. Child Abuse Negl. 2020, 99, 104315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, K.P.; Lee, S.J. Mothers’ and Fathers’ Parenting Stress, Responsiveness, and Child Wellbeing among Low-Income Families. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 116, 105218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kochanova, K.; Pittman, L.D.; Pabis, J.M. Parenting Stress, Parenting, and Adolescent Externalizing Problems. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2021, 30, 2141–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.; Young, J. Schema Therapy. In Handbook of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapies; Dobson, K.S., Ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 317–346. [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff, K.A.; Vazquez, L.C.; Lunkenheimer, E.S.; Cole, P.M. Longitudinal Changes in Young Children’s Strategy Use for Emotion Regulation. Dev. Psychol. 2021, 57, 1471–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wesarg-Menzel, C.; Ebbes, R.; Hensums, M.; Wagemaker, E.; Zaharieva, M.S.; Staaks, J.P.C.; Akker, A.L.; Visser, I.; Hoeve, M.; Brummelman, E.; et al. Development and Socialization of Self-Regulation from Infancy to Adolescence: A Meta-Review Differentiating between Self-Regulatory Abilities, Goals, and Motivation. Dev. Rev. 2023, 69, 101090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.L.; Yunes, M.A.M.; Nascimento, C.R.R.; Bedin, L.M. Children’s Subjective Well-Being, Peer Relationships and Resilience: An Integrative Literature Review. Child Indic. Res. 2021, 14, 1723–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wren, A. The Importance of Positive Peer Relationships for Child Well-Being and Resilience. In Childhood Well-Being and Resilience; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2020; pp. 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Kjeldsen, A.; Nes, R.B.; Sanson, A.; Ystrom, E.; Karevold, E.B. Understanding Trajectories of Externalizing Problems: Stability and Emergence of Risk Factors from Infancy to Middle Adolescence. Dev. Psychopathol. 2021, 33, 264–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponnet, K.; Wouters, E.; Mortelmans, D.; Pasteels, I.; Backer, C.; Leeuwen, K.; Hiel, A. The Influence of Mothers’ and Fathers’ Parenting Stress and Depressive Symptoms on Own and Partner’s Parent-Child Communication. Fam. Process 2013, 52, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Q.; Xu, Y.J. Dyadic Coping Mediates between Parenting Stress and Marital Adjustment among Parents of 0–6 Years Old Children. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2024, 33, 2337–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, L.; Feder, M.; Abar, B.; Winsler, A. Relations between Parenting Stress, Parenting Style, and Child Executive Functioning for Children with ADHD or Autism. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 3644–3656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemp, M.; Bodenmann, G.; Backes, S.; Sutter-Stickel, D.; Revenson, T.A. The Importance of Parents’ Dyadic Coping for Children. Fam. Relat. 2016, 65, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | % or Mean (SD) | N | % or Mean (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age at childbirth (years) | 404 | 30.1 (4.6) | Child sex | ||

| Paternal age at childbirth (years) | 400 | 34.1 (5.6) | Male | 214 | 52.7 |

| Maternal education | Female | 192 | 47.3 | ||

| Low | 41 | 10.2 | Gestational age (weeks) | 404 | 38.2 (1.5) |

| Medium | 203 | 50.4 | Preterm birth (<37 weeks) | ||

| High | 159 | 39.5 | Yes | 47 | 11.6 |

| Maternal working status | No | 357 | 88.4 | ||

| Employed | 314 | 79.7 | Mode of delivery | ||

| Not working/Unemployed | 80 | 20.3 | Vaginal | 207 | 51.0 |

| Maternal marital status | Cesarian section | 199 | 49.0 | ||

| Married | 362 | 90.7 | Birth anthropometry | ||

| Other | 37 | 9.3 | Weight (kg) | 405 | 3.2 (0.4) |

| Paternal education | Length (cm) | 405 | 50.6 (2.1) | ||

| Low | 114 | 28.8 | Head circumference (cm) | 405 | 34.2 (1.3) |

| Medium | 173 | 43.7 | Birth order | ||

| High | 109 | 27.5 | First | 159 | 44.2 |

| Paternal working status | Second | 132 | 36.7 | ||

| Employed | 398 | 99.5 | Third or more | 69 | 19.2 |

| Not working/Unemployed | 2 | 0.5 | Breastfeeding duration (months) | 397 | 4.3 (4.1) |

| Area of living | Nursery before 2 years | ||||

| Urban | 300 | 73.9 | Yes | 99 | 24.4 |

| Rural | 106 | 26.1 | No | 307 | 75.6 |

| Family origin | Exact age at assessment | ||||

| Greek | 382 | 95.3 | 4 years | 406 | 4.2 (0.2) |

| Foreign/Mixed | 19 | 4.7 | 6 years | 323 | 6.5 (0.3) |

| Household income (tertiles) | 11 years | 246 | 10.9 (0.3) | ||

| Low (<830 €/month) | 85 | 24.3 | 15 years | 354 | 14.9 (0.4) |

| Middle (831–1157 €/month) | 123 | 35.1 | Diagnosis | ||

| High (1158–2241 €/month) | 142 | 40.6 | None | 375 | 92.4 |

| Parity | Learning disabilities | 21 | 5.2 | ||

| Nulliparous | 176 | 44.8 | ADHD | 10 | 2.5 |

| Multiparous | 217 | 55.2 | |||

| Maternal smoking status during pregnancy | |||||

| Never | 248 | 62.5 | |||

| Ever | 149 | 37.5 |

| Overall | Males | Females | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD) | Min | Max | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | p-Value | |

| Internalizing symptoms | |||||||||

| SDQ 4 years | 406 | 3.2 (2.3) | 0 | 11 | 214 | 3.4 (2.4) | 192 | 3.0 (2.2) | 0.056 |

| CBCL 6 years | 320 | 5.9 (4.2) | 0 | 19 | 172 | 6.2 (4.3) | 148 | 5.5 (4.0) | 0.098 |

| CBCL 11 years | 244 | 7.0 (5.4) | 0 | 31 | 134 | 7.2 (5.6) | 110 | 6.7 (5.3) | 0.500 |

| CBCL 15 years | 352 | 6.7 (5.6) | 0 | 29 | 181 | 5.9 (5.0) | 171 | 7.6 (6.1) | 0.004 |

| Externalizing symptoms | |||||||||

| SDQ 4 years | 405 | 5.4 (3.1) | 0 | 16 | 214 | 5.8 (3.2) | 191 | 4.9 (2.8) | 0.001 |

| CBCL 6 years | 322 | 8.2 (6.3) | 0 | 38 | 173 | 9.4 (6.6) | 149 | 6.9 (5.6) | <0.001 |

| CBCL 11 years | 244 | 7.1 (6.5) | 0 | 36 | 134 | 8.1 (7.5) | 110 | 5.9 (4.9) | 0.010 |

| CBCL 15 years | 351 | 6.3 (6.2) | 0 | 42 | 181 | 6.5 (6.2) | 170 | 6.1 (6.2) | 0.539 |

| ADHD symptoms | |||||||||

| ADHDT 4 years | 405 | 14.9 (12.0) | 0 | 62 | 214 | 16.6 (13.0) | 191 | 13.0 (10.5) | 0.002 |

| CPRS 6 years | 317 | 8.6 (5.3) | 0 | 27 | 172 | 9.3 (5.4) | 145 | 7.8 (5.1) | 0.008 |

| CPRS 11 years | 246 | 8.2 (5.3) | 0 | 28 | 135 | 8.9 (5.6) | 111 | 7.3 (4.7) | 0.019 |

| CPRS 15 years | 353 | 7.8 (5.8) | 0 | 29 | 181 | 8.7 (5.8) | 172 | 6.8 (5.5) | 0.002 |

| Maternal Parenting Stress at 4 Years | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | Rho | p-Value | |

| Internalizing symptoms | |||

| 4 years | 406 | 0.288 | <0.001 |

| 6 years | 320 | 0.229 | <0.001 |

| 11 years | 244 | 0.177 | 0.006 |

| 15 years | 352 | 0.240 | <0.001 |

| Externalizing symptoms | |||

| 4 years | 405 | 0.319 | <0.001 |

| 6 years | 322 | 0.318 | <0.001 |

| 11 years | 244 | 0.171 | 0.008 |

| 15 years | 351 | 0.210 | <0.001 |

| ADHD symptoms | |||

| 4 years | 405 | 0.271 | <0.001 |

| 6 years | 317 | 0.257 | <0.001 |

| 11 years | 246 | 0.151 | 0.018 |

| 15 years | 353 | 0.215 | <0.001 |

| Maternal Parenting Stress at 4 Years | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ν | b (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Internalizing symptoms a | |||

| 4–15 years | 380 | 0.94 (0.68, 1.21) | <0.001 |

| Externalizing symptoms b | |||

| 4–15 years | 378 | 1.03 (0.75, 1.30) | <0.001 |

| ADHD symptoms b | |||

| 4–15 years | 381 | 0.86 (0.58, 1.14) | <0.001 |

| High Decreasing | Low Increasing | Stable High | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | RRR (95% CI) | p-Value | RRR (95% CI) | p-Value | RRR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Internalizing symptoms a | |||||||

| Parenting stress 4 years | 380 | 1.04 (1.01, 1.07) | 0.012 | 1.04 (1.00, 1.07) | 0.036 | 1.09 (1.04, 1.14) | <0.001 |

| Externalizing symptoms b | |||||||

| Parenting stress 4 years | 378 | 1.07 (1.03, 1.11) | <0.001 | 1.05 (1.01, 1.08) | 0.008 | 1.12 (1.07, 1.17) | <0.001 |

| ADHD symptoms b | |||||||

| Parenting stress 4 years | 381 | 1.07 (1.03, 1.11) | <0.001 | 1.02 (0.99, 1.06) | 0.209 | 1.10 (1.05, 1.15) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koutra, K.; Mouatsou, C.; Margetaki, K.; Mavroeides, G.; Kampouri, M.; Chatzi, L. From Early Stress to Adolescent Struggles: How Maternal Parenting Stress Shapes the Trajectories of Internalizing, Externalizing, and ADHD Symptoms. Pediatr. Rep. 2025, 17, 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17040076

Koutra K, Mouatsou C, Margetaki K, Mavroeides G, Kampouri M, Chatzi L. From Early Stress to Adolescent Struggles: How Maternal Parenting Stress Shapes the Trajectories of Internalizing, Externalizing, and ADHD Symptoms. Pediatric Reports. 2025; 17(4):76. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17040076

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoutra, Katerina, Chrysi Mouatsou, Katerina Margetaki, Georgios Mavroeides, Mariza Kampouri, and Lida Chatzi. 2025. "From Early Stress to Adolescent Struggles: How Maternal Parenting Stress Shapes the Trajectories of Internalizing, Externalizing, and ADHD Symptoms" Pediatric Reports 17, no. 4: 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17040076

APA StyleKoutra, K., Mouatsou, C., Margetaki, K., Mavroeides, G., Kampouri, M., & Chatzi, L. (2025). From Early Stress to Adolescent Struggles: How Maternal Parenting Stress Shapes the Trajectories of Internalizing, Externalizing, and ADHD Symptoms. Pediatric Reports, 17(4), 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17040076