Mindfulness in Mental Health and Psychiatric Disorders of Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Description of Included Studies

3.1.1. MBSR

3.1.2. MBCT

3.1.3. MBSR and MBCT

3.1.4. MBIs Not Specified

3.2. Meta-Analysis

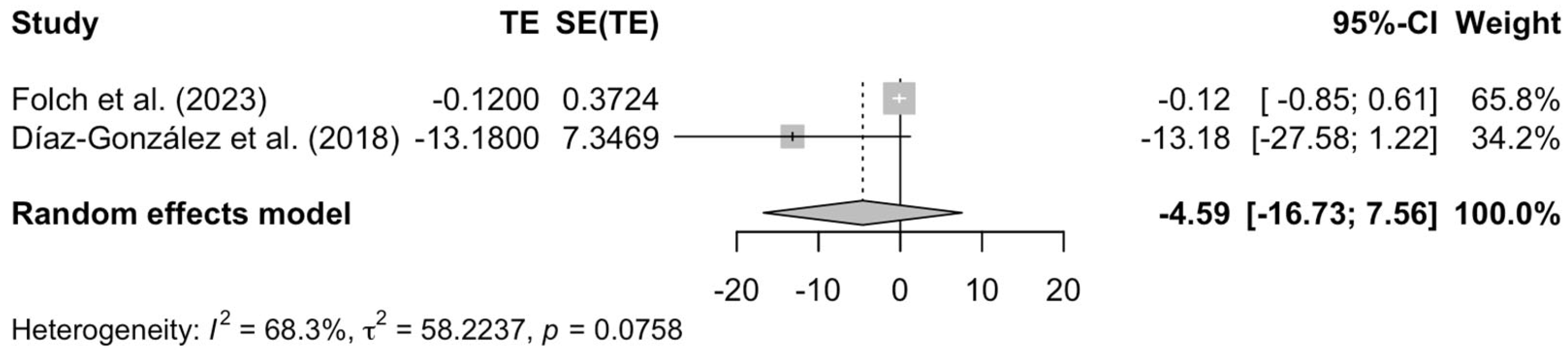

3.2.1. Effectiveness of Mindfulness Interventions in Depression

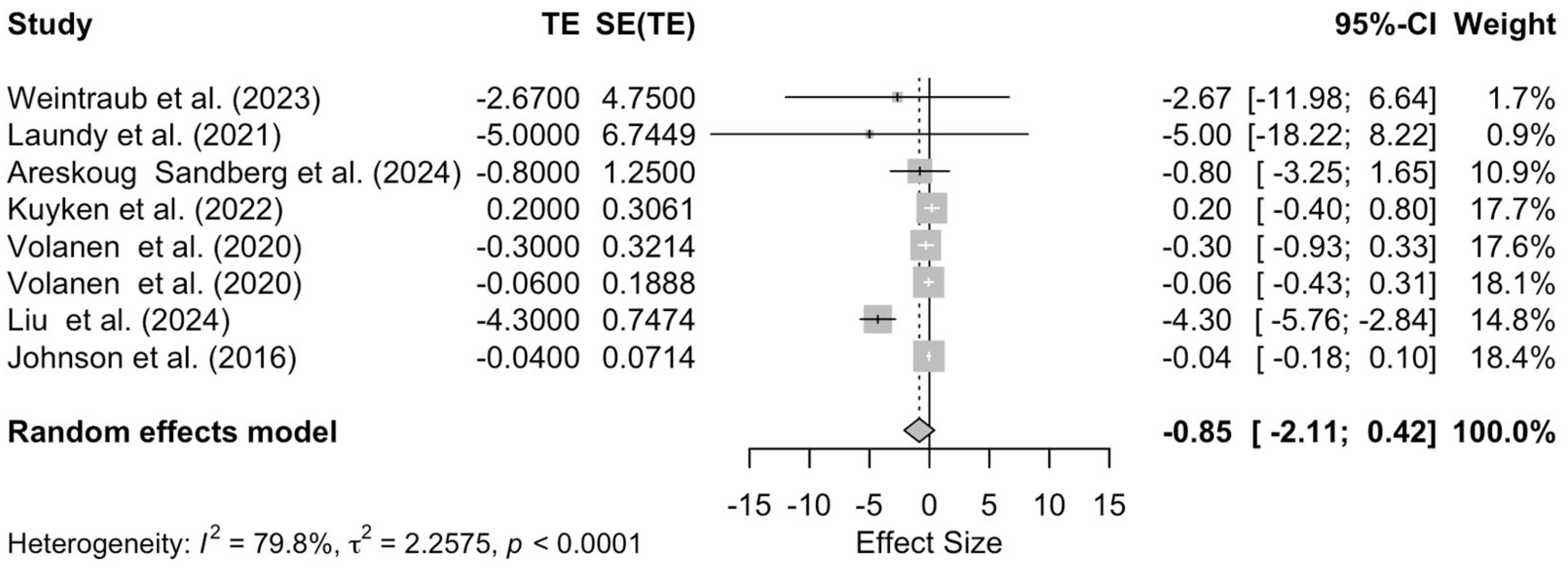

3.2.2. Effectiveness of Mindfulness Interventions in Anxiety

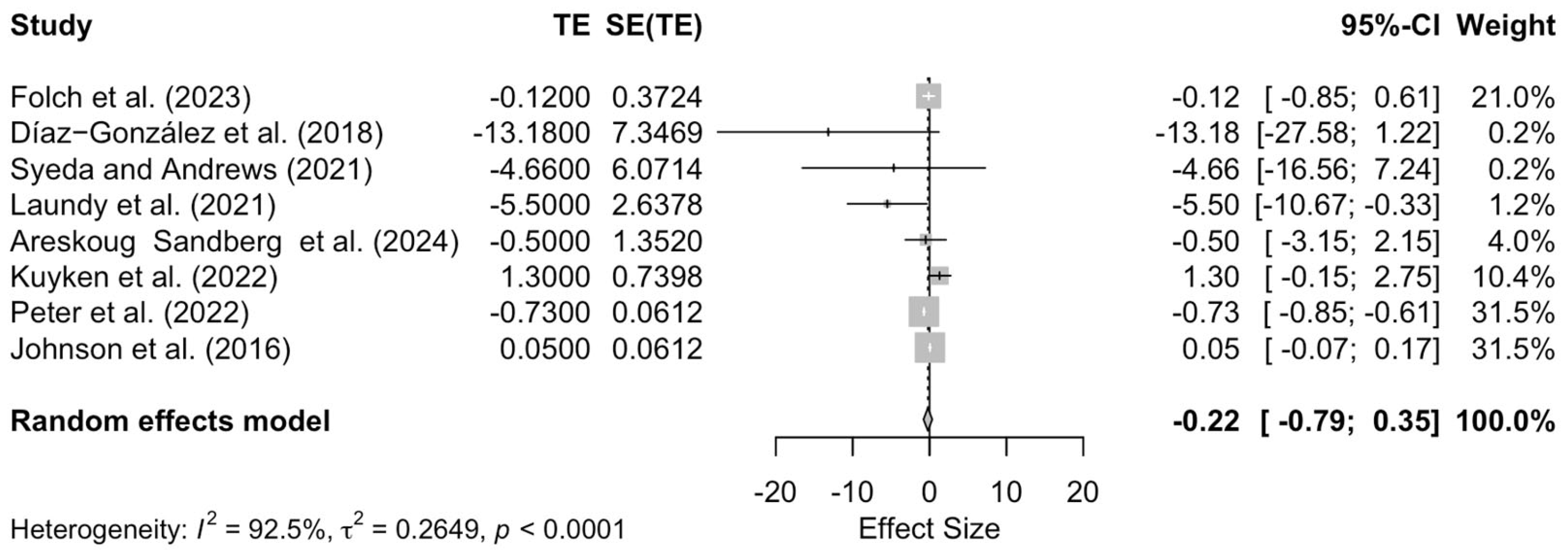

3.2.3. Effects of MBCT in Depression and Anxiety

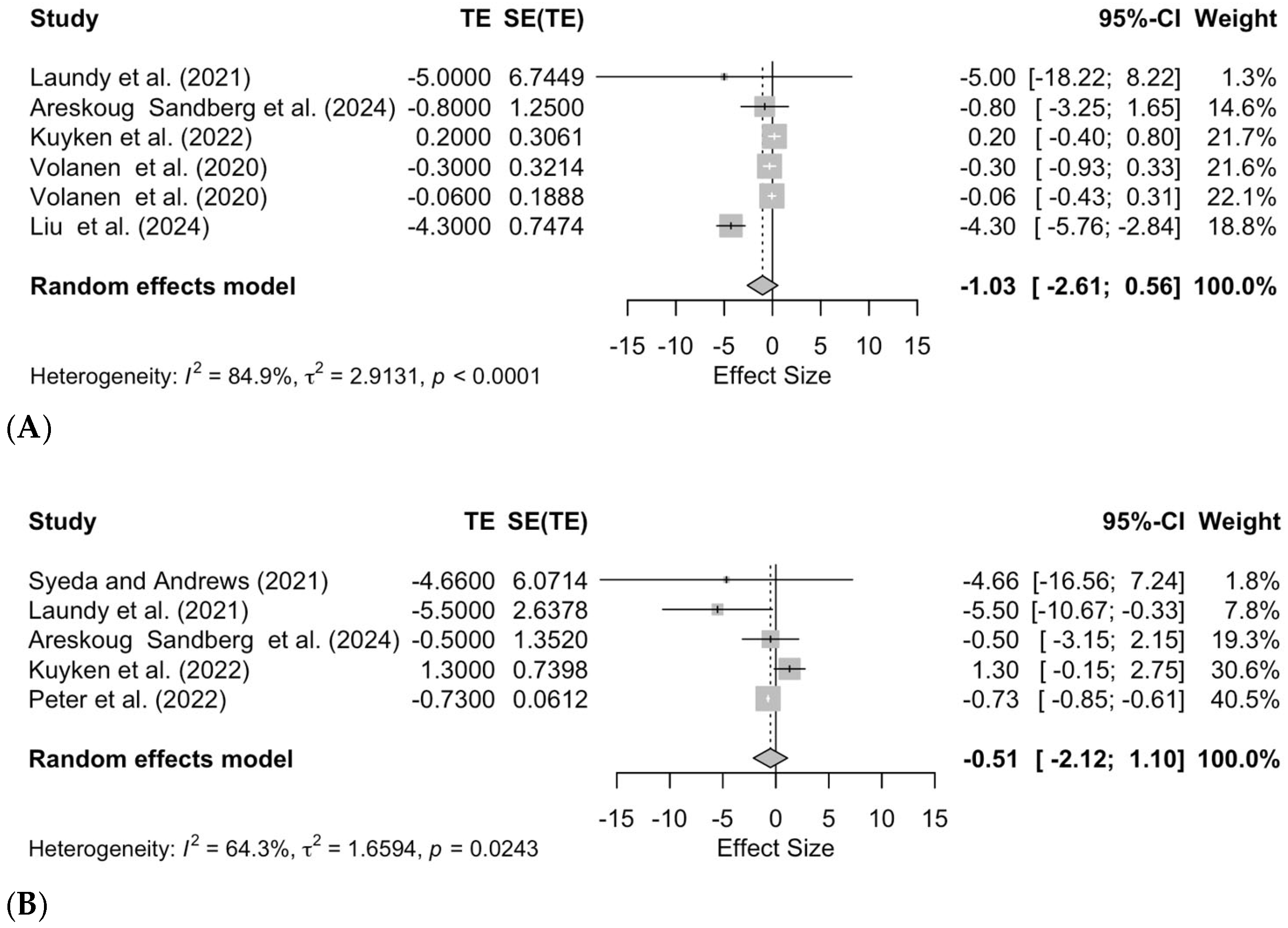

3.2.4. Effects of MBSR in Depression and Anxiety

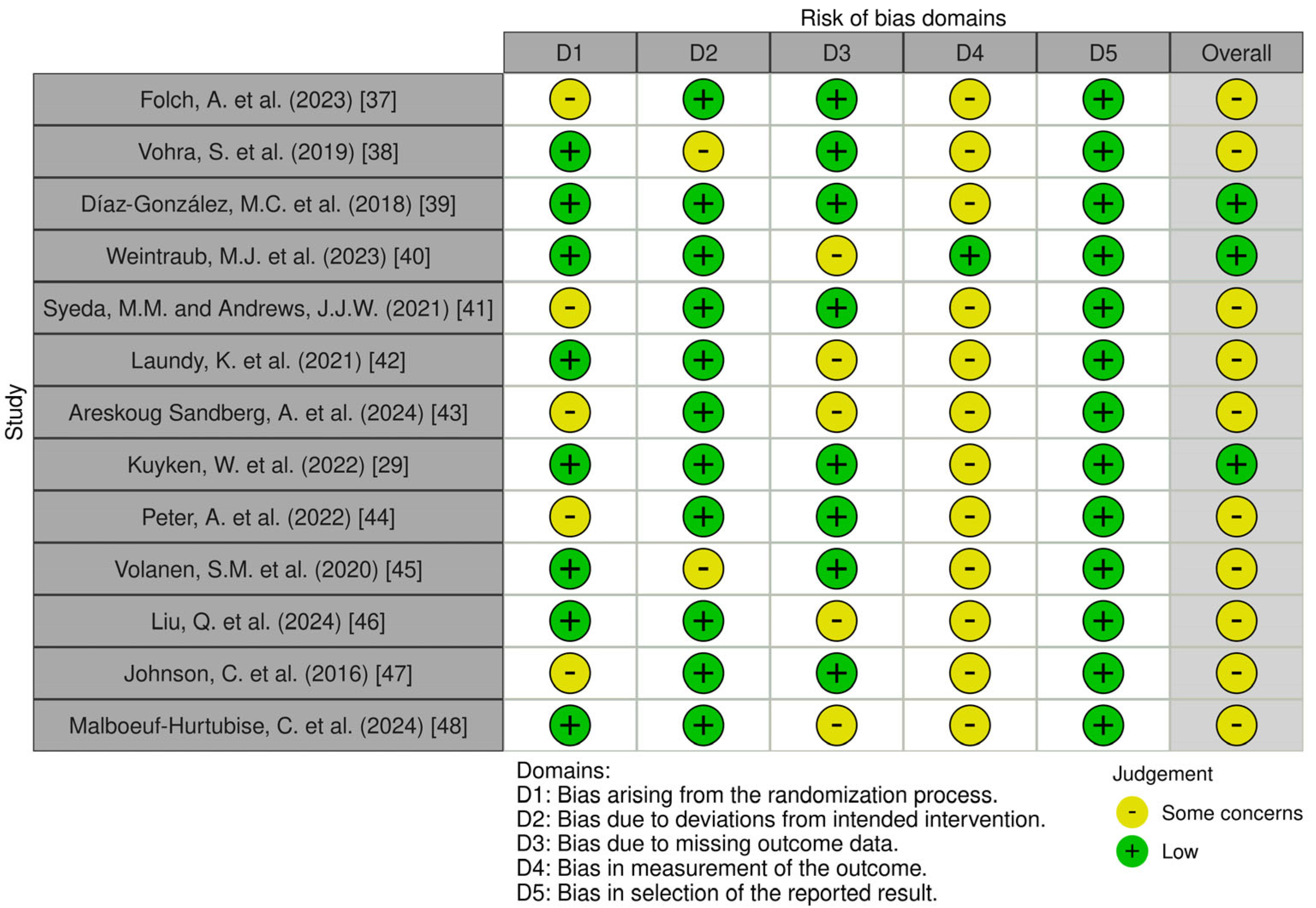

3.3. Risk of Bias

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MBIs | Mindfulness-Based Interventions |

| RCTs | Randomized Clinical Trials |

| PROSPERO | International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| MBSR | Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction |

| MBCT | Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy |

| MSC | Mindfulness Self-Compassion |

| MBRP | Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention |

| MORE | Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement |

| CBT | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| MD | Mean Difference |

| BASC-II | Behavior Assessment System for Children-II |

| BAI-Y | Beck Anxiety Inventory for Youth |

| BDI-Y | Beck Depression Inventory for Youth |

| BYI | Beck Youth Inventory |

| CES-D | Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale |

| DASS-21 | Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale-21 |

| MASC-2 | Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children-2 |

| PSS | Perceived Stress Scale |

| RCADS | Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| RBDI | Revised Beck Depression Inventory—Short |

| SCAS | Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale |

| SPECI | Screening for Children’s Emotional and Behavioral Problems |

| STAI | State-Trait Anxiety Inventory |

References

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Wherever You Go There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life, 11th ed.; Hyperion: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ie, A.; Ngnoumen, C.T.; Langer, E.J. The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Mindfulness, 1st ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Purser, R.E.; Forbes, D.; Burke, A. (Eds.) Handbook of Mindfulness: Culture, Context, and Social Engagement, 1st ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2003, 10, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, G.C.; Coffey, C.; Romaniuk, H.; Mackinnon, A.; Carlin, J.B.; Degenhardt, L.; Olsson, C.A.; Moran, P. The prognosis of common mental disorders in adolescents: A 14-year prospective cohort study. Lancet 2014, 383, 1404–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.A.; Silva, S.U.; Ronca, D.B.; Gonçalves, V.S.S.; Dutra, E.S.; Carvalho, K.M.B. Common mental disorders prevalence in adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analyses. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favaretto, E.; Bedani, F.; Brancati, G.E.; De Berardis, D.; Giovannini, S.; Scarcella, L.; Martiadis, V.; Martini, A.; Pampaloni, I.; Perugi, G.; et al. Synthesising 30 years of clinical experience and scientific insight on affective temperaments in psychiatric disorders: State of the art. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 362, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reb, J.; Atkins, P.W.B. Mindfulness in Organizations: Foundations, Research, and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, M.; Heerkens, Y.; Kuijer, W.; van der Heijden, B.; Engels, J. Effects of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction on employees’ mental health: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness, 15th Anniversary ed.; Delta Trade Paperback: New York, NY, USA; Bantam Dell: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 33–471. [Google Scholar]

- Khoury, B.; Sharma, M.; Rush, S.E.; Fournier, C. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: A meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2015, 78, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, S.; Greeson, J.M.; Reibel, D.K.; Green, J.S.; Jasser, S.A.; Beasley, D. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for chronic pain conditions: Variation in treatment outcomes and role of home meditation practice. J. Psychosom. Res. 2010, 68, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipe, W.E.B.; Eisendrath, S.J. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy: Theory and Practice. Can. J. Psychiatry 2012, 57, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuyken, W.; Warren, F.C.; Taylor, R.S.; Whalley, B.; Crane, C.; Bondolfi, G.; Hayes, R.; Huijbers, M.; Ma, H.; Schweizer, S.; et al. Efficacy of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy in Prevention of Depressive Relapse: An Individual Patient Data Meta-analysis From Randomized Trials. JAMA Psychiatry 2016, 73, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, M.C. Caring for the caregivers: Evaluation of the effect of an eight-week pilot mindful self-compassion (MSC) training program on nurses’ compassion fatigue and resilience. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, S.A.; Kissane, D.; Meadows, G. Cognitive effects of MBSR/MBCT: A systematic review of neuropsychological outcomes. Conscious. Cogn. 2016, 45, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neff, K.D. Self-Compassion: Theory, Method, Research, and Intervention. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2023, 74, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torrijos-Zarcero, M.; Mediavilla, R.; Rodríguez-Vega, B.; Del Río-Diéguez, M.; López-Álvarez, I.; Rocamora-González, C.; Palao-Tarrero, Á. Mindful Self-Compassion program for chronic pain patients: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Pain 2021, 25, 930–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, S.; Witkiewitz, K.; Clifasefi, S.L.; Grow, J.; Chawla, N.; Hsu, S.H.; Carroll, H.A.; Harrop, E.; Collins, S.E.; Lustyk, M.K.; et al. Relative efficacy of mindfulness-based relapse prevention, standard relapse prevention, and treatment as usual for substance use disorders: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2014, 71, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, D.C.; Marlatt, G.A. Overcoming Your Alcohol or Drug Problem: Effective Recovery Strategies; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Garland, E.L. Mindful Positive Emotion Regulation as a Treatment for Addiction: From Hedonic Pleasure to Self-Transcendent Meaning. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2021, 39, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, E.L.; Fredrickson, B.L. Positive psychological states in the arc from mindfulness to self-transcendence: Extensions of the Mindfulness-to-Meaning Theory and applications to addiction and chronic pain treatment. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 28, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, A.W.; Nakamura, Y.; Garland, E.L. The Nondual Awareness Dimensional Assessment (NADA): New tools to assess nondual traits and states of consciousness occurring within and beyond the context of meditation. Psychol. Assess. 2018, 30, 1625–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, A.; Roberts, R.L.; Hanley, A.W.; Garland, E.L. Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement for Addictive Behavior, Psychiatric Distress, and Chronic Pain: A Multilevel Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Mindfulness 2022, 13, 2396–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Marin, J.; Allwood, M.; Ball, S.; Crane, C.; De Wilde, K.; Hinze, V.; Jones, B.; Lord, L.; Nuthall, E.; Raja, A.; et al. School-based mindfulness training in early adolescence: What works, for whom and how in the MYRIAD trial? Evid.-Based Ment. Health 2022, 25, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudor, K.; Maloney, S.; Raja, A.; Baer, R.; Blakemore, S.-J.; Byford, S.; Crane, C.; Dalgleish, T.; De Wilde, K.; Ford, T.; et al. Universal Mindfulness Training in Schools for Adolescents: A Scoping Review and Conceptual Model of Moderators, Mediators, and Implementation Factors. Prev. Sci. 2022, 23, 934–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, D.M.; Davies, S.R.; Hetrick, S.E.; Palmer, J.C.; Caro, P.; López-López, J.A.; Gunnell, D.; Kidger, J.; Thomas, J.; French, C.; et al. School-based interventions to prevent anxiety and depression in children and young people: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 1011–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zenner, C.; Herrnleben-Kurz, S.; Walach, H. Mindfulness-based interventions in schools—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuyken, W.; Ball, S.; Crane, C.; Ganguli, P.; Jones, B.; Montero-Marin, J.; Nuthall, E.; Raja, A.; Taylor, L.; Tudor, K.; et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of universal school-based mindfulness training compared with normal school provision in reducing risk of mental health problems and promoting well-being in adolescence: The MYRIAD cluster randomised controlled trial. Evid.-Based Ment. Health 2022, 25, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.; Mychailyszyn, M. The Effect of School-Based Mindfulness Interventions on Anxious and Depressive Symptoms: A Meta-analysis. Sch. Ment. Health 2022, 14, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem. Med. 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, L.A.; Higgins, J.P.T. Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): An R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Res. Synth. Methods 2021, 12, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, R.; Kongasseri, S.; Rai, S. Efficacy of Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy on Children with Anxiety. J. Cogn. Psychother. 2020, 34, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folch, A.; Gasol, L.; Heredia, L.; Vicens, P.; Torrente, M. Mindful schools: Neuropsychological performance after the implementation of a mindfulness-based structured program in the school setting. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 12118–12128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohra, S.; Punja, S.; Sibinga, E.; Baydala, L.; Wikman, E.; Singhal, A.; Dolcos, F.; Van Vliet, K.J. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for mental health in youth: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2019, 24, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-González, M.C.; Pérez Dueñas, C.; Sánchez-Raya, A.; Moriana Elvira, J.A.; Sánchez Vázquez, V. Mindfulness-based stress reduction in adolescents with mental disorders: A randomised clinical trial. Psicothema 2018, 30, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weintraub, M.J.; Denenny, D.; Ichinose, M.C.; Zinberg, J.; Morgan-Fleming, G.; Done, M.; Brown, R.D.; Bearden, C.E.; Miklowitz, D.J. A randomized trial of telehealth mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy groups for adolescents with mood or attenuated psychosis symptoms. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2023, 91, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syeda, M.M.; Andrews, J.J.W. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy as a targeted group intervention: Examining children’s changes in anxiety symptoms and mindfulness. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2021, 30, 1002–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laundy, K.; Friberg, P.; Osika, W.; Chen, Y. Mindfulness-Based Intervention for Children with Mental Health Problems: A 2-Year Follow-up Randomized Controlled Study. Mindfulness 2021, 12, 3073–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areskoug Sandberg, E.; Stenman, E.; Palmer, K.; Duberg, A.; Sundquist, J.; Sundquist, K. A 10-Week School-Based Mindfulness Intervention and Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety Among School Children and Adolescents: A Controlled Study. Sch. Ment. Health 2024, 16, 936–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, A.; Srivastava, R.; Agarwal, A.; Singh, A.P. The Effect of Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy on Anxiety and Resilience of the School Going Early Adolescents with Anxiety. J. Indian Assoc. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 18, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volanen, S.M.; Lassander, M.; Hankonen, N.; Santalahti, P.; Hintsanen, M.; Simonsen, N.; Raevuori, A.; Mullola, S.; Vahlberg, T.; But, A.; et al. Healthy learning mind—Effectiveness of a mindfulness program on mental health compared to a relaxation program and teaching as usual in schools: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 260, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yang, X.; Zhang, C.; Xiong, J. Is decreasing problematic mobile phone use a pathway for alleviating adolescent depression and sleep disorders? A randomized controlled trial testing the effectiveness of an eight-session mindfulness-based intervention. J. Behav. Addict. 2024, 13, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.; Burke, C.; Brinkman, S.; Wade, T. Effectiveness of a school-based mindfulness program for transdiagnostic prevention in young adolescents. Behav. Res. Ther. 2016, 81, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C.; Taylor, G.; Lambert, D.; Paradis, P.O.; Léger-Goodes, T.; Mageau, G.A.; Labbé, G.; Smith, J.; Joussemet, M. Impact of a mindfulness-based intervention on well-being and mental health of elementary school children: Results from a randomized cluster trial. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C.; Lacourse, É. Mission méditation: Pour des élèves épanouis, calmes et concentrés; Éditions Midi Trente: Québec, CA, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bohlmeijer, E.; Prenger, R.; Taal, E.; Cuijpers, P. The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction therapy on mental health of adults with a chronic medical disease: A meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2010, 68, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanck, P.; Perleth, S.; Heidenreich, T.; Kröger, P.; Ditzen, B.; Bents, H.; Mander, J. Effects of mindfulness exercises as stand-alone intervention on symptoms of anxiety and depression: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav. Res. Ther. 2018, 102, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberth, J.; Sedlmeier, P. The Effects of Mindfulness Meditation: A Meta-Analysis. Mindfulness 2012, 3, 174–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, D.L.; Griffiths, K.; Kuyken, W.; Crane, C.; Foulkes, L.; Parker, J.; Dalgleish, T. Research Review: The effects of mindfulness-based interventions on cognition and mental health in children and adolescents—A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2019, 60, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingbeil, D.A.; Renshaw, T.L.; Willenbrink, J.B.; Copek, R.A.; Chan, K.T.; Haddock, A.; Yassine, J.; Clifton, J. Mindfulness-based interventions with youth: A comprehensive meta-analysis of group-design studies. J. Sch. Psychol. 2017, 63, 77–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampogna, G.; Della Rocca, B.; Di Vincenzo, M.; Catapano, P.; Del Vecchio, V.; Volpicelli, A.; Martiadis, V.; Signorelli, M.S.; Ventriglio, A.; Fiorillo, A. Innovations and criticisms of the organization of mental health care in Italy. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2024, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsley, D.; Khoury, B.; Heath, N.L. Effectiveness of Mindfulness Interventions for Mental Health in Schools: A Comprehensive Meta-analysis. Mindfulness 2018, 9, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B.M.; Mickes, L.; Stolarz-Fantino, S.; Evrard, M.; Fantino, E. Increased False-Memory Susceptibility After Mindfulness Meditation. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 26, 1567–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, C.A. Mindfulness-Based Approaches with Children and Adolescents: A Preliminary Review of Current Research in an Emergent Field. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2010, 19, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Semple, R.J.; Rosa, D.; Miller, L. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Children: Results of a Pilot Study. J. Cogn. Psychother. 2008, 22, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, C.; Whittingham, K.; Cunnington, R.; Boyd, R.N. Efficacy of Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Attention and Executive Function in Children and Adolescents—A Systematic Review. Mindfulness 2018, 9, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bögels, S.; Hoogstad, B.; van Dun, L.; de Schutter, S.; Restifo, K. Mindfulness Training for Adolescents with Externalizing Disorders and their Parents. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2008, 36, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors (Year) | Country | Sample Characteristics | Total N | Age (Years) | Intervention (N) | Control (N) | Period of Intervention | Outcome Measure | Effect Size (95% CI) | Effectiveness of Mindfulness Interventions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Folch, A. et al. (2023) [37] | Spain | Female and male students in 5th or 6th grade | 100 | 9 to 11 | MBSR (69) | No intervention (31) | 13 weeks | SPECI | MD = −0.12 (−0.85, 0.61) | + |

| Vohra, S. et al. (2019) [38] | Canada | Female and male students with a history of not responding to previous mental health interventions and requiring a high degree of intensive treatment | 81 | 12 to 18 | MBSR (42) | Usual treatment (39) | 10 weeks | PSS | MD = −0.88 (−4.08, 2.32) | + |

| Díaz-González, M.C. et al. (2018) [39] | Spain | Female and male students with mental health disorders | 80 | 13 to 16 | MBSR (41) | Usual treatment (39) | 8 weeks | STAI | MD = −13.18 (−27.58, 1.22) | + |

| Weintraub, M.J. et al. (2023) [40] | United States of America | Female and male students with a mood disorder, namely depression | 54 | 13 to 17 | MBSR (30) | CBT (24) | 2 months | CDRS | MD = −2.67 (−12.01, 6.61) | + |

| Syeda, M.M. and Andrews, J.J.W. (2021) [41] | Canada | Female and male students with anxiety disorder | 19 | 9 to 12 | MBCT (11) | No intervention (8) | 4 weeks | MASC-2 | MD = −4.66 (−22.54, 1.26) | + |

| Laundy, K. et al. (2021) [42] | Sweden | Female and male students with mental health disorders, namely anxiety disorders and depressive disorders | 34 | 9 to 14 | MBCT (22) | No intervention (12) | 8 weeks | BYI | MD = −5.00 (−18.22, 8.22), depression at 1 year post-intervention | + |

| MD = −5.50 (−10.67, −0.33), anxiety at 1 year post-intervention) | + + | |||||||||

| Areskoug Sandberg, A. et al. (2024) [43] | Sweden | Female and male students in 3rd to 9th grade | 1394 | 9 to 16 | MBCT (902) | No intervention (492) | 10 weeks | BDI-Y, depression | MD = −0.80 (−1.70, 3.20) | + |

| BAI-Y, anxiety | MD = −0.50 (−2.10, 3.20) | + | ||||||||

| Kuyken, W. et al. (2022) [29] | United Kingdom | Female and male students in 7th to 10th grade | 7561 | 11 to 16 | MBCT especially directed at students (3768) | Usual treatment (3793) | 28 weeks | CES-D, depression | MD = 0.20 (−0.40, 0.80) | − |

| RCADS, anxiety | MD = 1.30 (−0.20, 2.70) | − | ||||||||

| Peter, A. et al. (2022) [44] | India | Female and male students with anxiety | 65 | 12 to 14 | MBCT (33) | No intervention (32) | 12 weeks | SCAS | MD = −0.73 (−0.61, −0.85) | + + |

| Volanen, S.M. et al. (2020) [45] | Finland | Female and male students in 6th to 8th grade | 2254 | 12 to 15 | MBCT (1020) | No intervention (277) | 9 weeks | RBDI | MD = −0.30 (−0.93, 0.33) | + |

| Relaxation program (957) | MD = −0.06 (−0.43, 0.31) | + | ||||||||

| Liu, Q. et al. (2024) [46] | China | Female and male students in 7th to 12th grade | 94 | 12 to 18 | MBCT (45) | No intervention (49) | 8 weeks | DASS-21 | MD = −4.30 (−5.76, −2.83) | + + |

| Johnson, C. et al. (2016) [47] | Australia | Female and male students | 269 | 13.63 ± 0.43 | MBCT/MBSR (115) | No intervention (154) | 8 weeks | DASS-21 | MD = −0.04 (−0.18, 0.10), depression | + |

| MD = 0.05 (−0.07, 0.17), anxiety | − | |||||||||

| Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C. et al. (2024) [48] | Canada | Female and male students in 3rd to 6th grade | 231 | 8 to 12 | MBIs, not specified (127) | No intervention (104) | 10 weeks | BASC-II | Coef = 0.45 (−0.36, 1.26), depression | + |

| Coef = 0.16 (−0.32, 0.64), anxiety | + |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carneiro, B.D.; Pozza, D.H.; Costa-Pereira, J.T.; Tavares, I. Mindfulness in Mental Health and Psychiatric Disorders of Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Pediatr. Rep. 2025, 17, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17030059

Carneiro BD, Pozza DH, Costa-Pereira JT, Tavares I. Mindfulness in Mental Health and Psychiatric Disorders of Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Pediatric Reports. 2025; 17(3):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17030059

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarneiro, Bruno Daniel, Daniel Humberto Pozza, José Tiago Costa-Pereira, and Isaura Tavares. 2025. "Mindfulness in Mental Health and Psychiatric Disorders of Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials" Pediatric Reports 17, no. 3: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17030059

APA StyleCarneiro, B. D., Pozza, D. H., Costa-Pereira, J. T., & Tavares, I. (2025). Mindfulness in Mental Health and Psychiatric Disorders of Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Pediatric Reports, 17(3), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17030059