Self-Efficacy and Psychological Well-Being in Adolescents: Evaluating the Moderating Role of Socioeconomic Status and Cultural Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Background

1.2. Positive and Negative Affect and the Relationships with Socioeconomic Status and Immigrant Background

1.3. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Future Directions

4.2. Educational Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beauchaine, T.P.; Hinshaw, S.P. Child and Adolescent Psychopathology; John Wiley & Sons Inc: Hoboken, NI, USA, 2008; ISBN 9780415475976. [Google Scholar]

- Zyberaj, J. Investigating the Relationship between Emotion Regulation Strategies and Self-Efficacy Beliefs Among Adolescents: Implications for Academic Achievement. Psychol. Sch. 2022, 59, 1556–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Multidimensional Scales of Perceived Academic Efficacy; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Caprara, G.V.; Fida, R.; Vecchione, M.; Del Bove, G.; Vecchio, G.M.; Barbaranelli, C.; Bandura, A. Longitudinal Analysis of the Role of Perceived Self-Efficacy for Self-Regulated Learning in Academic Continuance and Achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. 2008, 100, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, U. Student Engagement, Academic Self-Efficacy, and Academic Motivation as Predictors of Academic Performance. Anthropologist 2015, 20, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honicke, T.; Broadbent, J. The Influence of Academic Self-Efficacy on Academic Performance: A Systematic Review. Educ. Res. Rev. 2016, 17, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazzaglia, F.; Moè, A.; Cipolletta, S.; Chia, M.; Galozzi, P.; Masiero, S.; Punzi, L. Multiple Dimensions of Self-Esteem and Their Relationship with Health in Adolescence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W.H. Freeman and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Young, K.S.; Sandman, C.F.; Craske, M.G. Positive and Negative Emotion Regulation in Adolescence: Links to Anxiety and Depression. Brain Sci. 2019, 9, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.; Wang, X.; Dai, D.Y.; Guo, X.; Xiang, S.; Hu, W. Academic Self-Efficacy and Academic Performance among High School Students: A Moderated Mediation Model of Academic Buoyancy and Social Support. Psychol. Sch. 2022, 59, 885899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alivernini, F.; Cavicchiolo, E.; Manganelli, S. Brothers, Ants or Thieves: Students’ Complex Attitudes towards Immigrants and the Role of Socioeconomic Status and Gender in Shaping Them. Social. Psychol. Educ. 2019, 22, 629–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alivernini, F. An Exploration of the Gap between Highest and Lowest Ability Readers across 20 Countries. Educ. Stud. 2013, 39, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demanet, J.; Van Houtte, M. Socioeconomic Status, Economic Deprivation, and School Misconduct: An Inquiry into the Role of Academic Self-Efficacy in Four European Cities. Social. Psychol. Educ. 2019, 22, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paletta, A.; Alivernini, F.; Manganelli, S. Leadership for Learning: The Relationships between School Context, Principal Leadership and Mediating Variables. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2017, 31, 98–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broer, M.; Bai, Y.; Fonseca, F. Socioeconomic Inequality and Educational Outcomes; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 16, ISBN 9783030119904. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, L.; McConney, A. School Socio-Economic Composition and Student Outcomes in Australia: Implications for Educational Policy. Aust. J. Educ. 2010, 54, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, L.; Spinath, F.M.; Hahn, E. How Do Educational Inequalities Develop? The Role of Socioeconomic Status, Cognitive Ability, Home Environment, and Self-Efficacy along the Educational Path. Intelligence 2021, 86, 101528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sucuoğlu, E. Economic Status, Self-Efficacy and Academic Achievement: The Case Study of Undergraduate Students. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Global Education Monitoring Report, 2019: Migration, Displacement and Education: Building Bridges, Not Walls; UNESCO: Pairs, France, 2019.

- Cavicchiolo, E.; Manganelli, S.; Bianchi, D.; Biasi, V.; Lucidi, F.; Girelli, L.; Cozzolino, M.; Alivernini, F. Social Inclusion of Immigrant Children at School: The Impact of Group, Family and Individual Characteristics, and the Role of Proficiency in the National Language. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2023, 27, 146–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, D.; Cavicchiolo, E.; Manganelli, S.; Lucidi, F.; Girelli, L.; Cozzolino, M.; Galli, F.; Alivernini, F. Bullying and Victimization in Native and Immigrant Very-Low-Income Adolescents in Italy: Disentangling the Roles of Peer Acceptance and Friendship. Child. Youth Care Forum 2021, 50, 1013–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Equity in Education: Breaking Down Barriers to Social Mobility; PISA; OECD: Paris, France, 2018; ISBN 9789264056732.

- Dimitrova, R.; Chasiotis, A.; Van De Vijver, F. Adjustment Outcomes of Immigrant Children and Youth in Europe: A Meta-Analysis. Eur. Psychol. 2016, 21, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebauer, M.M.; McElvany, N.; Köller, O.; Schöber, C. Cross-Cultural Differences in Academic Self-Efficacy and Its Sources across Socialization Contexts. Social. Psychol. Educ. 2021, 24, 1407–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Farah, M.J. The Affective Neuroscience of Socioeconomic Status: Implications for Mental Health. BJPsych Bull. 2020, 44, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alivernini, F.; Cavicchiolo, E.; Manganelli, S.; Chirico, A.; Lucidi, F. Students’ Psychological Well-Being and Its Multilevel Relationship with Immigrant Background, Gender, Socioeconomic Status, Achievement, and Class Size. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2019, 31, 172–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gard, A.M.; Waller, R.; Shaw, D.S.; Forbes, E.E.; Hariri, A.R.; Hyde, L.W. The Long Reach of Early Adversity: Parenting, Stress, and Neural Pathways to Antisocial Behavior in Adulthood. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2017, 2, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, P.; Capistrano, C.G.; Erhart, A.; Gray-Schiff, R.; Xu, N. Socioeconomic Disadvantage, Neural Responses to Infant Emotions, and Emotional Availability among First-Time New Mothers. Behav. Brain Res. 2017, 325, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romens, S.E.; Casement, M.D.; McAloon, R.; Keenan, K.; Hipwell, A.E.; Guyer, A.E.; Forbes, E.E. Adolescent Girls’ Neural Response to Reward Mediates the Relation between Childhood Financial Disadvantage and Depression. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2015, 56, 1177–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahal, D.; Shaw, S.T.; Stigler, J.W. Lower Socioeconomic Status Is Related to Poorer Emotional Well-Being Prior to Academic Exams. Anxiety Stress. Coping 2023, 36, 502–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moeller, J.; Brackett, M.A.; Ivcevic, Z.; White, A.E. High School Students’ Feelings: Discoveries from a Large National Survey and an Experience Sampling Study. Learn. Instr. 2020, 66, 101301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarello, F.; Manganelli, S.; Cavicchiolo, E.; Lucidi, F.; Chirico, A.; Alivernini, F. Addressing Adolescents’ Prejudice toward Immigrants: The Role of the Classroom Context. J. Youth Adolesc. 2023, 52, 951–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavicchiolo, E.; Manganelli, S.; Girelli, L.; Chirico, A.; Lucidi, F.; Alivernini, F. Immigrant Children’s Proficiency in the Host Country Language Is More Important than Individual, Family and Peer Characteristics in Predicting Their Psychological Well-Being. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2020, 22, 1225–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X. English Language Proficiency, Academic Language Difficulties and Self-Efficacy: A Comparative Study of International and Home Students in UK Higher Education. Ph.D. Thesis, University of York, York, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, D.; Cavicchiolo, E.; Lucidi, F.; Manganelli, S.; Girelli, L.; Chirico, A.; Alivernini, F. School Dropout Intention and Self-Esteem in Immigrant and Native Students Living in Poverty: The Protective Role of Peer Acceptance at School. School Ment. Health 2021, 13, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondy, J.M.; Peguero, A.A.; Johnson, B.E. The Children of Immigrants’ Academic Self-Efficacy: The Significance of Gender, Race, Ethnicity, and Segmented Assimilation. Educ. Urban. Soc. 2017, 49, 486–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schotte, K.; Stanat, P.; Edele, A. Is Integration Always Most Adaptive? The Role of Cultural Identity in Academic Achievement and in Psychological Adaptation of Immigrant Students in Germany. J. Youth Adolesc. 2018, 47, 16–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manganelli, S.; Cavicchiolo, E.; Lucidi, F.; Galli, F.; Cozzolino, M.; Chirico, A.; Alivernini, F. Differences and Similarities in Adolescents’ Academic Motivation across Socioeconomic and Immigrant Backgrounds. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2021, 182, 111077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, M.E.; Muennig, P.; Liu, X.; Rosen, Z.; Goldstein, M.A. The Impact of Socioeconomic Status on the Neural Substrates Associated with Pleasure. Open Neuroimaging J. 2009, 3, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for the Evaluation of the Education System Rilevazioni Nazionali Sugli Apprendimenti 2014–2015 [National Evaluations on Learning 2014–2015] Author. Available online: https://invalsi-areaprove.cineca.it/docs/attach/035_Rapporto_Prove_INVALSI_2015.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Bandura, A.; Barbaranelli, C.; Caprara, G.V.; Pastorelli, C. Multifaceted Impact of Self-Efficacy Beliefs on Academic Functioning. Child. Dev. 1996, 67, 1206–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, D.; Cavicchiolo, E.; Manganelli, S.; Lucidi, F.; Chirico, A.; Girelli, L.; Cozzolino, M.; Alivernini, F. School Absenteeism and Self-Efficacy in Very-Low-Income Students in Italy: Cross-Lagged Relationships and Differential Effects of Immigrant Background. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2022, 136, 106446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimondi, G.; Manganelli, S.; Cavicchiolo, E.; Zacchilli, M.; Palombi, T.; Chirico, A.; Lucidi, F.; Alivernini, F. Exploring Academic Self-Efficacy for Self-Regulated Learning: The Role of Socioeconomic Status, Immigrant Background, and Biological Sex. Psychol. Sch. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G.V. (Ed.) La Valutazione Dell’autoefficacia. Interventi e Contesti Culturali; Erikson: Trento, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pastorelli, C.; Caprara, G.V.; Barbaranelli, C.; Rola, J.; Rozsa, S.; Bandura, A. The Structure of Children’s Perceived Self-Efficacy: A Cross-National Study. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2001, 17, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) PISA 2012 Technical Report. Programme for International Student Assessment, OECD Publishing. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/pisa/pisaproducts/PISA-2012-technical-report-final.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Satorra, A.; Bentler, P. A Scaled Difference Chi-Square Test Statistic for Moment Structure Analysis. Psychometrika 2001, 66, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacker, R.; Lomax, R.G. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; Routledge Taylor & Francis Group: Oxfordshire, UK, 2012; Volume 175, ISBN 9781841698908. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative Fit Indexes in Structure Models. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance Tests and Goodness of Fit in the Analysis of Covariance Structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 21, 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.Y. Evaluating Cutoff Criteria of Model Fit Indices for Latent Variable Models with Binary and Continuous Outcomes; University of California: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.F. Sensitivity of Goodness of Fit Indexes to Lack of Measurement Invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 2007, 14, 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 8th ed.; Muthén and Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Shavers, V.L. Measurement of Socioeconomic Status in Health Disparities Research. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2007, 99, 1013–1023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vadivel, B.; Alam, S.; Nikpoo, I.; Ajanil, B. The Impact of Low Socioeconomic Background on a Child’s Educational Achievements. Educ. Res. Int. 2023, 11, 6565088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.D.; Anderson, K.E.; Garnett, M.L.; Hill, E.M. Economic Instability and Household Chaos Relate to Cortisol for Children in Poverty. J. Fam. Psychol. 2019, 33, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conner, M.; McEachan, R.; Jackson, C.; McMillan, B.; Woolridge, M.; Lawton, R. Moderating Effect of Socioeconomic Status on the Relationship between Health Cognitions and Behaviors. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 46, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilburn, J. Challenges Facing Immigrant Students beyond the Linguistic Domain in a New Gateway State. Urban. Rev. 2014, 46, 654–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, N.; Archer, J. School Socio-Economic Status and Student Socio-Academic Achievement Goals in Upper Secondary Contexts. Social. Psychol. Educ. 2016, 19, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulinou, I. Striving to Make the Difference: Linguistic Devices of Moral Indignation. J. Lang. Aggress. Confl. 2014, 2, 74–98. [Google Scholar]

- Poggi, I.; D’Errico, F. The Mental Ingredients of Bitterness. J. Multimodal User Interfaces 2010, 3, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paciello, M.; Corbelli, G.; D’Errico, F. The Role of Self-Efficacy Beliefs in Dealing with Misinformation among Adolescents. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1155280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alivernini, F.; Manganelli, S.; Cavicchiolo, E.; Girelli, L.; Biasi, V.; Lucidi, F. Immigrant Background and Gender Differences in Primary Students’ Motivations toward Studying. J. Educ. Res. 2018, 111, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SES | |||||||||||

| Model | χ2 | df | ∆χ2 | ∆df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | ΔCFI | ΔRMSEA | ΔSRMR |

| Model-1 | 3307.01 | 195 | - | - | 0.958 | 0.957 | 0.043 | 0.034 | - | - | - |

| Model-2 | 3320.19 | 199 | 13.18 | 4 | 0.958 | 0.958 | 0.042 | 0.035 | 0 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Immigrant Background | |||||||||||

| Model | χ2 | df | ∆χ2 | ∆df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | ΔCFI | ΔRMSEA | ΔSRMR |

| Model-1 | 3438.24 | 195 | - | - | 0.957 | 0.957 | 0.044 | 0.034 | - | - | - |

| Model-2 | 3454.57 | 199 | 16.33 | 4 | 0.957 | 0.957 | 0.043 | 0.035 | 0 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

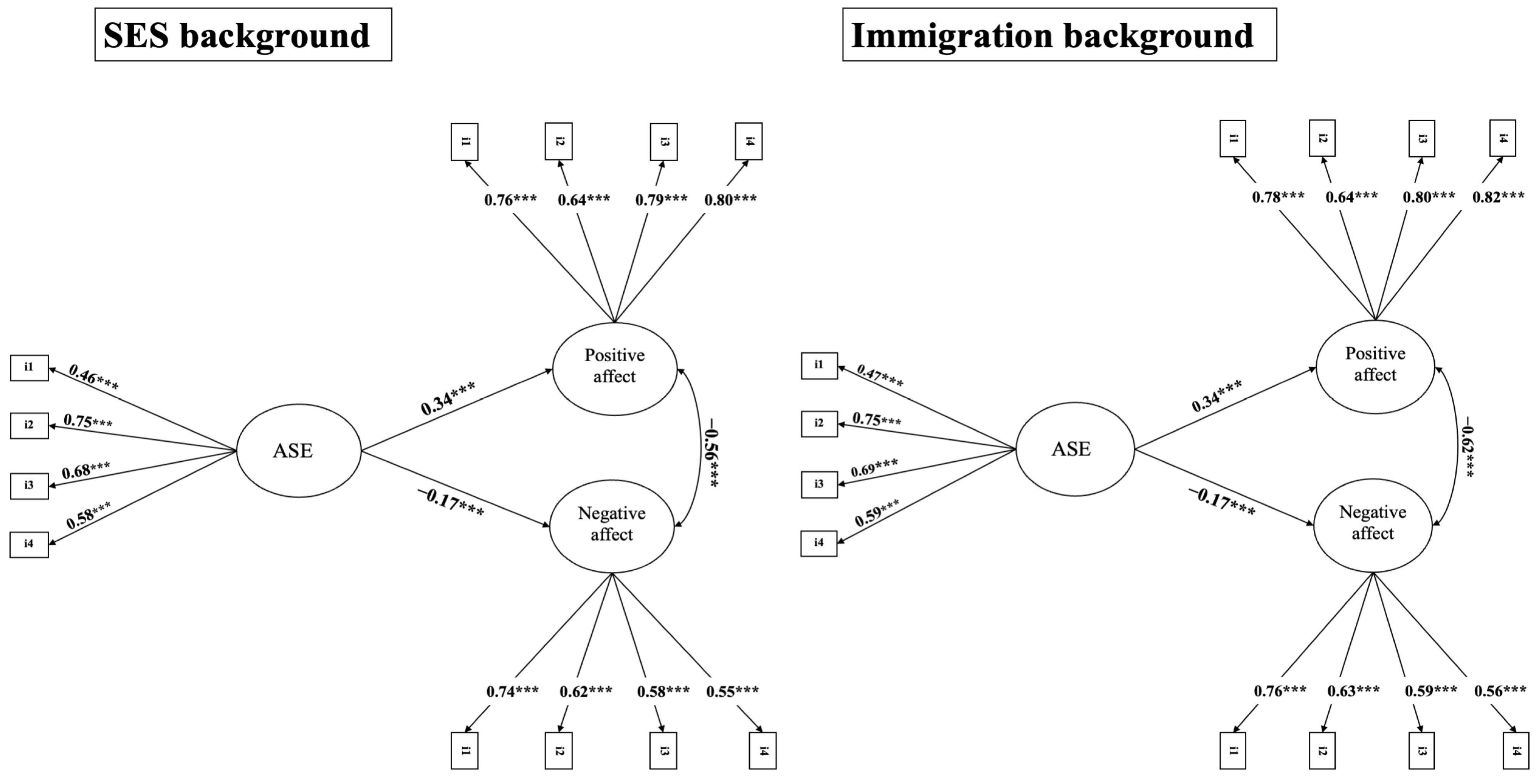

| Model | Positive Affect | Negative Affect |

|---|---|---|

| ASE × low SES interaction | 0.35 *** | −0.15 *** |

| ASE × medium SES interaction | 0.34 *** | −0.18 *** |

| ASE × high SES interaction | 0.32 *** | −0.18 *** |

| ASE × native adolescents interaction | 0.33 *** | −0.17 *** |

| ASE × 1st-generation immigrant adolescents interaction | 0.42 *** | −0.13 *** |

| ASE × 2nd-generation immigrant adolescents interaction | 0.37 *** | −0.13 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Raimondi, G.; Dawe, J.; Alivernini, F.; Manganelli, S.; Diotaiuti, P.; Mandolesi, L.; Zacchilli, M.; Lucidi, F.; Cavicchiolo, E. Self-Efficacy and Psychological Well-Being in Adolescents: Evaluating the Moderating Role of Socioeconomic Status and Cultural Factors. Pediatr. Rep. 2025, 17, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17020039

Raimondi G, Dawe J, Alivernini F, Manganelli S, Diotaiuti P, Mandolesi L, Zacchilli M, Lucidi F, Cavicchiolo E. Self-Efficacy and Psychological Well-Being in Adolescents: Evaluating the Moderating Role of Socioeconomic Status and Cultural Factors. Pediatric Reports. 2025; 17(2):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17020039

Chicago/Turabian StyleRaimondi, Giulia, James Dawe, Fabio Alivernini, Sara Manganelli, Pierluigi Diotaiuti, Laura Mandolesi, Michele Zacchilli, Fabio Lucidi, and Elisa Cavicchiolo. 2025. "Self-Efficacy and Psychological Well-Being in Adolescents: Evaluating the Moderating Role of Socioeconomic Status and Cultural Factors" Pediatric Reports 17, no. 2: 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17020039

APA StyleRaimondi, G., Dawe, J., Alivernini, F., Manganelli, S., Diotaiuti, P., Mandolesi, L., Zacchilli, M., Lucidi, F., & Cavicchiolo, E. (2025). Self-Efficacy and Psychological Well-Being in Adolescents: Evaluating the Moderating Role of Socioeconomic Status and Cultural Factors. Pediatric Reports, 17(2), 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17020039