Probiotic Potential of Pediococcus acidilactici SWP-CGPA01: Alleviating Antibiotic-Induced Diarrhea and Restoring Hippocampal BDNF

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains and Culture Conditions

2.2. Genome Sequencing and Analysis

2.3. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

2.4. Mucin Degradation Assay

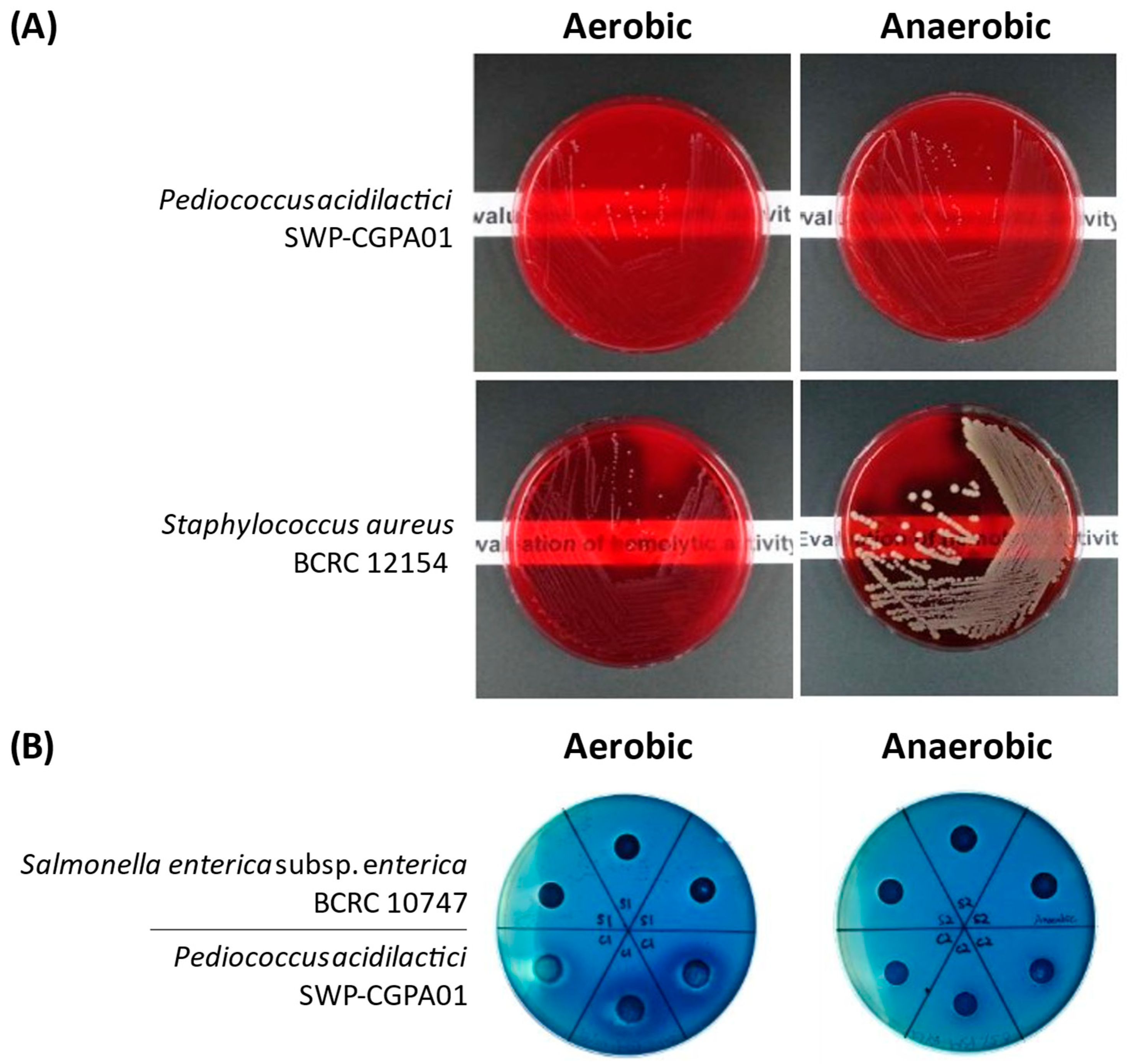

2.5. Hemolytic Activity Assay

2.6. Biogenic Amine Analysis

2.7. Gastric Acid–Bile Salt Tolerance Test

2.8. Animals and In Vivo Experimental Design

2.9. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Genotypic Characterization-Based Safety Assessment of P. acidilactici SWP-CGPA01

3.2. Bioinformatic-Based Identification of Antibiotic Resistance and Pathogenicity of P. acidilactici SWP-CGPA01

3.3. Phenotypic Characterization-Based Safety Assessment of P. acidilactici SWP-CGPA01

3.4. Effects of P. acidilactici SWP-CGPA01 in Antibiotic-Associated Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SWP-CGPA01 | Pediococcus acidilactici SWP-CGPA01 |

| WGS | Whole-genome sequence |

| BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| SCFAs | Short-chain fatty acids |

| ONT | Oxford Nanopore Technology |

| BUSCOs | Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs |

| wgMLST | Whole-genome multi-locus sequence typing |

| MIC | Minimum inhibitory concentration |

| PSM | Porcine submaxillary mucin |

| MRS | De Man–Rogosa–Sharpe |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| NCB | National Center for Biomodels |

| IACUC | Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee |

| TOSs | Transgalactosylated oligosaccharides |

| MUP | Lithium-Mupirocin |

| TOS-MUP | Transgalactosylated oligosaccharides–mupirocin medium |

| ANI | Average nucleotide identity |

| dDDH | Digital DNA-DNA hybridization |

| GBDP | Genome BLAST Distance Phylogeny |

| cgMLST | Core genome multi-locus sequence typing |

| EFSA | European Food Safety |

| QPS | Qualified Presumption of Safety |

References

- Abeles, S.R.; Jones, M.B.; Santiago-Rodriguez, T.M.; Ly, M.; Klitgord, N.; Yooseph, S.; Nelson, K.E.; Pride, D.T. Microbial Diversity in Individuals and Their Household Contacts Following Typical Antibiotic Courses. Microbiome 2016, 4, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keely, S.J.; Barrett, K.E. Intestinal Secretory Mechanisms and Diarrhea. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2022, 322, G405–G420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, L.V. Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea: Epidemiology, Trends and Treatment. Future Microbiol. 2008, 3, 563–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandpal, M.; Indari, O.; Baral, B.; Jakhmola, S.; Tiwari, D.; Bhandari, V.; Pandey, R.K.; Bala, K.; Sonawane, A.; Jha, H.C. Dysbiosis of Gut Microbiota from the Perspective of the Gut–Brain Axis: Role in the Provocation of Neurological Disorders. Metabolites 2022, 12, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, H.J. Role of Colonic Short-Chain Fatty Acid Transport in Diarrhea. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2010, 72, 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bistoletti, M.; Caputi, V.; Baranzini, N.; Marchesi, N.; Filpa, V.; Marsilio, I.; Cerantola, S.; Terova, G.; Baj, A.; Grimaldi, A.; et al. Antibiotic Treatment-Induced Dysbiosis Differently Affects BDNF and TrkB Expression in the Brain and in the Gut of Juvenile Mice. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, Y.P.; Bernardi, A.; Frozza, R.L. The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids from Gut Microbiota in Gut-Brain Communication. Front. Endocrinol 2020, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.P.; Rubio, L.A.; Duncan, S.H.; Donachie, G.E.; Holtrop, G.; Lo, G.; Farquharson, F.M.; Wagner, J.; Parkhill, J.; Louis, P.; et al. Pivotal Roles for pH, Lactate, and Lactate-Utilizing Bacteria in the Stability of a Human Colonic Microbial Ecosystem. mSystems 2020, 5, e00645-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosi, A.; Banfi, D.; Bistoletti, M.; Giaroni, C.; Baj, A. Tryptophan Metabolites along the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis: An Interkingdom Communication System Influencing the Gut in Health and Disease. Int. J. Tryptophan Res. 2020, 13, 1178646920928984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyei-Baffour, V.O.; Vijaya, A.K.; Burokas, A.; Daliri, E.B.M. Psychobiotics and the Gut-Brain Axis: Advances in Metabolite Quantification and Their Implications for Mental Health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 7085–7104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, R.; Bouzari, B.; Hosseini-Fard, S.R.; Mazaheri, M.; Ahmadyousefi, Y.; Abdi, M.; Jalalifar, S.; Karimitabar, Z.; Teimoori, A.; Keyvani, H.; et al. Role of Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Nervous System Disorders. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 139, 111661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, W.; Zadeh, K.; Vekariya, R.; Ge, Y.; Mohamadzadeh, M. Tryptophan Metabolism and Gut-Brain Homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Xu, J.; Yang, B.; Chen, K.; Kong, Y.; Fang, N.; Gong, T.; Wang, F.; Ling, Z.; Liu, J. Effect of Clostridium butyricum against Microglia-Mediated Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s Disease via Regulating Gut Microbiota and Metabolites Butyrate. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2020, 64, 1900636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.S.; Jung, S.; Hwang, G.S.; Shin, D.M. Gut Microbiota Indole-3-Propionic Acid Mediates Neuroprotective Effect of Probiotic Consumption in Healthy Elderly: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Multicenter Trial and in Vitro Study. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 42, 1025–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards (BIOHAZ); Allende, A.; Alvarez-Ordóñez, A.; Bortolaia, V.; Bover-Cid, S.; De Cesare, A.; Dohmen, W.; Guillier, L.; Jacxsens, L.; Nauta, M.; et al. Update of the List of Qualified Presumption of Safety (QPS) Recommended Microbiological Agents Intentionally Added to Food or Feed as Notified to EFSA 21: Suitability of Taxonomic Units Notified to EFSA until September 2024. EFSA J. 2025, 23, e9169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.M.; Martínez, M.I.; Kok, J. Pediocin PA-1, a Wide-Spectrum Bacteriocin from Lactic Acid Bacteria. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2002, 42, 91–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello-Olmo, M.; Oneca, M.; Pajares, M.J.; Jiménez, M.; Ayo, J.; Encío, I.J.; Barajas, M.; Araña, M. Antidiabetic Effects of Pediococcus acidilactici pA1c on HFD-Induced Mice. Nutrients 2022, 14, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Guo, W.L.; Chen, G.M.; Qian, M.; Han, J.Z.; Lv, X.C.; Chen, L.J.; Rao, P.F.; Ai, L.Z.; Ni, L. Pediococcus acidilactici FZU106 Alleviates High-Fat Diet-Induced Lipid Metabolism Disorder in Association with the Modulation of Intestinal Microbiota in Hyperlipidemic Rats. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2022, 5, 775–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myo, N.Z.; Kamwa, R.; Jamnong, T.; Swasdipisal, B.; Somrak, P.; Rattanamalakorn, P.; Neatsawang, V.; Apiwatsiri, P.; Yata, T.; Hampson, D.J.; et al. Metabolomic Profiling and Antibacterial Efficacy of Probiotic-Derived Cell-Free Supernatant Encapsulated in Nanostructured Lipid Carriers against Canine Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 11, 1525897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Song, Q.; Wang, M.; Ren, J.; Liu, S.; Zhao, S. Comparative Genomics Analysis of Pediococcus acidilactici Species. J. Microbiol. 2021, 59, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, K.; Bao, K.; Li, G. Impact of Pediococcus acidilactici GLP06 Supplementation on Gut Microbes and Metabolites in Adult Beagles: A Comparative Analysis. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1369402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myo, N.Z.; Kamwa, R.; Khurajog, B.; Pupa, P.; Sirichokchatchawan, W.; Hampson, D.J.; Prapasarakul, N. Industrial Production and Functional Profiling of Probiotic Pediococcus acidilactici 72 N for Potential Use as a Swine Feed Additive. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.; Chen, Y.; Qian, X.; Zou, R.; Zhu, H.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, G.; Chen, W. Pediococcus acidilactici CCFM6432 Mitigates Chronic Stress-Induced Anxiety and Gut Microbial Abnormalities. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 11241–11249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.E.; Smith, J.; Lam, M.; Zemla, A.; Dyer, M.D.; Slezak, T. MvirDB—A Microbial Database of Protein Toxins, Virulence Factors and Antibiotic Resistance Genes for Bio-Defence Applications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, D391–D394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zheng, D.; Liu, B.; Yang, J.; Jin, Q. VFDB 2016: Hierarchical and Refined Dataset for Big Data Analysis—10 Years On. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D694–D697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joensen, K.G.; Scheutz, F.; Lund, O.; Hasman, H.; Kaas, R.S.; Nielsen, E.M.; Aarestrup, F.M. Real-Time Whole-Genome Sequencing for Routine Typing, Surveillance, and Outbreak Detection of Verotoxigenic Escherichia coli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 1501–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosentino, S.; Voldby Larsen, M.; Møller Aarestrup, F.; Lund, O. PathogenFinder-Distinguishing Friend from Foe Using Bacterial Whole Genome Sequence Data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e77302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.H.; Park, Y.K.; Kim, J.F. PAIDB v2. 0: Exploration and Analysis of Pathogenicity and Resistance Islands. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, D624–D630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Ge, Q.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Huang, L.; Yin, Y. dbCAN3: Automated Carbohydrate-Active Enzyme and Substrate Annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W115–W121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldgarden, M.; Brover, V.; Haft, D.H.; Prasad, A.B.; Slotta, D.J.; Tolstoy, I.; Tyson, G.H.; Zhao, S.; Hsu, C.-H.; McDermott, P.F.; et al. Validating the AMRFinder Tool and Resistance Gene Database by Using Antimicrobial Resistance Genotype-Phenotype Correlations in a Collection of Isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcock, B.P.; Raphenya, A.R.; Lau, T.T.Y.; Tsang, K.K.; Bouchard, M.; Edalatmand, A.; Huynh, W.; Nguyen, A.L.V.; Cheng, A.A.; Liu, S.; et al. CARD 2020: Antibiotic Resistome Surveillance with the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D517–D525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zankari, E.; Hasman, H.; Cosentino, S.; Vestergaard, M.; Rasmussen, S.; Lund, O.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Larsen, M.V. Identification of Acquired Antimicrobial Resistance Genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 2640–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.K.; Padmanabhan, B.R.; Diene, S.M.; Lopez-Rojas, R.; Kempf, M.; Landraud, L.; Rolain, J.M. ARG-ANNOT, a New Bioinformatic Tool To Discover Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Bacterial Genomes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aramaki, T.; Blanc-Mathieu, R.; Endo, H.; Ohkubo, K.; Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S.; Ogata, H. KofamKOALA: KEGG Ortholog Assignment Based on Profile HMM and Adaptive Score Threshold. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 2251–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertelli, C.; Laird, M.R.; Williams, K.P.; Simon Fraser University Research Computing Group; Lau, B.Y.; Hoad, G.; Winsor, G.L.; Brinkman, F.S. IslandViewer 4: Expanded Prediction of Genomic Islands for Larger-Scale Datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W30–W35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Tang, H. ISEScan: Automated Identification of Insertion Sequence Elements in Prokaryotic Genomes. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 3340–3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirén, K.; Millard, A.; Petersen, B.; Gilbert, M.T.P.; Clokie, M.R.; Sicheritz-Pontén, T. Rapid Discovery of Novel Prophages Using Biological Feature Engineering and Machine Learning. NAR Genom. Bioinf. 2021, 3, lqaa109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellow, D.; Mizrahi, I.; Shamir, R. PlasClass Improves Plasmid Sequence Classification. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2020, 16, e1007781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couvin, D.; Bernheim, A.; Toffano Nioche, C.; Touchon, M.; Michalik, J.; Néron, B.; Rocha, E.P.; Vergnaud, G.; Gautheret, D.; Pourcel, C. CRISPRCasFinder, an Update of CRISRFinder, Includes a Portable Version, Enhanced Performance and Integrates Search for Cas Proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W246–W251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.; Machado, M.P.; Silva, D.N.; Rossi, M.; Moran-Gilad, J.; Santos, S.; Ramirez, M.; Carrico, J.A. chewBBACA: A Complete Suite for Gene-by-Gene Schema Creation and Strain Identification. Microb. Genom. 2018, 4, e000166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 10932: 2012; Milk and Milk Products—Determination of the Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of Antibiotics Applicable to Bifidobacteria and Non-Enterococcal Lactic Acid Bacteria. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- EFSA Panel on Additives and Products or Substances used in Animal Feed (FEEDAP); Rychen, G.; Aquilina, G.; Azimonti, G.; Bampidis, V.; de Lourdes Bastos, M.; Bories, G.; Chesson, A.; Cocconcelli, P.S.; Flachowsky, G.; et al. Guidance on the Characterisation of Microorganisms Used as Feed Additives or as Production Organisms. EFSA J. 2018, 16, e05206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.S.; Gopal, P.K.; Gill, H.S. Potential Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria Lactobacillus rhamnosus (HN001), Lactobacillus acidophilus (HN017) and Bifidobacterium lactis (HN019) Do Not Degrade Gastric Mucin in Vitro. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2001, 63, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casarotti, S.N.; Carneiro, B.M.; Todorov, S.D.; Nero, L.A.; Rahal, P.; Penna, A.L.B. In Vitro Assessment of Safety and Probiotic Potential Characteristics of Lactobacillus Strains Isolated from Water Buffalo Mozzarella Cheese. Ann. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Bi, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, G.; Hao, H.; Hou, H. Contribution of Microorganisms to Biogenic Amine Accumulation during Fish Sauce Fermentation and Screening of Novel Starters. Foods 2021, 10, 2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.H.; Lee, J.H.; Park, Y.K.; Lee, J.H.; Mah, J.H. The Occurrence of Biogenic Amines and Determination of Biogenic Amine-Producing Lactic Acid Bacteria in Kkakdugi and Chonggak Kimchi. Foods 2019, 8, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, H.; Grimmer, S.; Naterstad, K.; Axelsson, L. In Vitro Testing of Commercial and Potential Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 153, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Yu, L.; Tian, F.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Zhai, Q. Effects of Bacteroides-Based Microecologics against Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea in Mice. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Qi, Y.; Chen, L.; Qu, D.; Li, Z.; Gao, K.; Chen, J.; Sun, Y. Effects of Panax ginseng Polysaccharides on the Gut Microbiota in Mice with Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 124, 931–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.S.; Huang, Y.Y.; Kuang, J.H.; Yu, J.J.; Zhou, Q.Y.; Liu, D.M. Streptococcus thermophiles DMST-H2 Promotes Recovery in Mice with Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riesco, R.; Trujillo, M.E. Update on the Proposed Minimal Standards for the Use of Genome Data for the Taxonomy of Prokaryotes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2024, 74, 006300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Auch, A.F.; Klenk, H.P.; Göker, M. Genome Sequence-Based Species Delimitation with Confidence Intervals and Improved Distance Functions. BMC Bioinform. 2013, 14, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turna, N.S.; Chung, R.; McIntyre, L. A Review of Biogenic Amines in Fermented Foods: Occurrence and Health Effects. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Ed-Dra, A.; Yue, M. Whole Genome Sequencing for the Risk Assessment of Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 11244–11262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Additives and Products or Substances used in Animal Feed. Guidance on the Assessment of Bacterial Susceptibility to Antimicrobials of Human and Veterinary Importance. EFSA J. 2012, 10, 2740. [CrossRef]

- Lüdin, P.; Roetschi, A.; Wüthrich, D.; Bruggmann, R.; Berthoud, H.; Shani, N. Update on Tetracycline Susceptibility of Pediococcus acidilactici Based on Strains Isolated from Swiss Cheese and Whey. J. Food Prot. 2018, 81, 1582–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuoker, B.; Pichler, M.J.; Jin, C.; Sakanaka, H.; Wu, H.; Gascueña, A.M.; Liu, J.; Nielsen, T.S.; Holgersson, J.; Nordberg Karlsson, E.; et al. Sialidases and Fucosidases of Akkermansia muciniphila Are Crucial for Growth on Mucin and Nutrient Sharing with Mucus-Associated Gut Bacteria. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruas-Madiedo, P.; Gueimonde, M.; Fernández-García, M.; de los Reyes-Gavilán, C.G.; Margolles, A. Mucin Degradation by Bifidobacterium Strains Isolated from the Human Intestinal Microbiota. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 1936–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassarella, M.; Blaak, E.E.; Penders, J.; Nauta, A.; Smidt, H.; Zoetendal, E.G. Gut Microbiome Stability and Resilience: Elucidating the Response to Perturbations in Order to Modulate Gut Health. Gut 2021, 70, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Ding, C.; Zhao, W.; Xu, L.; Tian, H.; Gong, J.; Zhu, M.; Li, J.; Li, N. Antibiotics-Induced Depletion of Mice Microbiota Induces Changes in Host Serotonin Biosynthesis and Intestinal Motility. J. Transl. Med. 2017, 15, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Huh, J.R.; Shah, K. Microbiota and the Gut-Brain-Axis: Implications for New Therapeutic Design in the CNS. eBioMedicine 2022, 77, 103908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhong, R.; Su, D.; Xia, B.; Liu, L.; Chen, L.; Zhang, H. Time-Course Alterations of Gut Microbiota and Short-Chain Fatty Acids after Short-Term Lincomycin Exposure in Young Swine. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 8441–8456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thabet, E.; Dief, A.E.; Arafa, S.A.F.; Yakout, D.; Ali, M.A. Antibiotic-Induced Gut Microbe Dysbiosis Alters Neurobehavior in Mice through Modulation of BDNF and Gut Integrity. Physiol. Behav. 2024, 283, 114621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Antibiotics | Cut-Off Values of Pediococcus spp. (mg/L) | SWP-CGPA01 | BCRC 17599 |

|---|---|---|---|

| MICs (mg/L) | MICs (mg/L) | ||

| Ampicillin | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| Gentamicin | 16 | 8 | 4 |

| Kanamycin | 64 | 128 | 64 |

| Streptomycin | 64 | 32 | 64 |

| Erythromycin | 1 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Clindamycin | 1 | 0.063 | 0.032 |

| Tetracycline | 8 | 16 | 16 |

| Chloramphenicol | 4 | 16 | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.-Z.; Chen, C.-T.; Shih, T.-W.; Hsu, W.-H.; Lee, B.-H.; Pan, T.-M. Probiotic Potential of Pediococcus acidilactici SWP-CGPA01: Alleviating Antibiotic-Induced Diarrhea and Restoring Hippocampal BDNF. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 16, 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16120261

Chen Y-Z, Chen C-T, Shih T-W, Hsu W-H, Lee B-H, Pan T-M. Probiotic Potential of Pediococcus acidilactici SWP-CGPA01: Alleviating Antibiotic-Induced Diarrhea and Restoring Hippocampal BDNF. Microbiology Research. 2025; 16(12):261. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16120261

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, You-Zuo, Chieh-Ting Chen, Tsung-Wei Shih, Wei-Hsuan Hsu, Bao-Hong Lee, and Tzu-Ming Pan. 2025. "Probiotic Potential of Pediococcus acidilactici SWP-CGPA01: Alleviating Antibiotic-Induced Diarrhea and Restoring Hippocampal BDNF" Microbiology Research 16, no. 12: 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16120261

APA StyleChen, Y.-Z., Chen, C.-T., Shih, T.-W., Hsu, W.-H., Lee, B.-H., & Pan, T.-M. (2025). Probiotic Potential of Pediococcus acidilactici SWP-CGPA01: Alleviating Antibiotic-Induced Diarrhea and Restoring Hippocampal BDNF. Microbiology Research, 16(12), 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16120261