Structure-Based Identification of Ponganone V from Pongamia pinnata as a Potential KPC-2 β-Lactamase Inhibitor: Insights from Docking, ADMET, and Molecular Dynamics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Molecular Docking

2.1.1. Receptor Preparation

2.1.2. Ligand Preparation

2.1.3. Docking Protocol

2.2. ADMET Analysis

2.3. Molecular Dynamics Simulations

3. Results

3.1. Molecular Docking

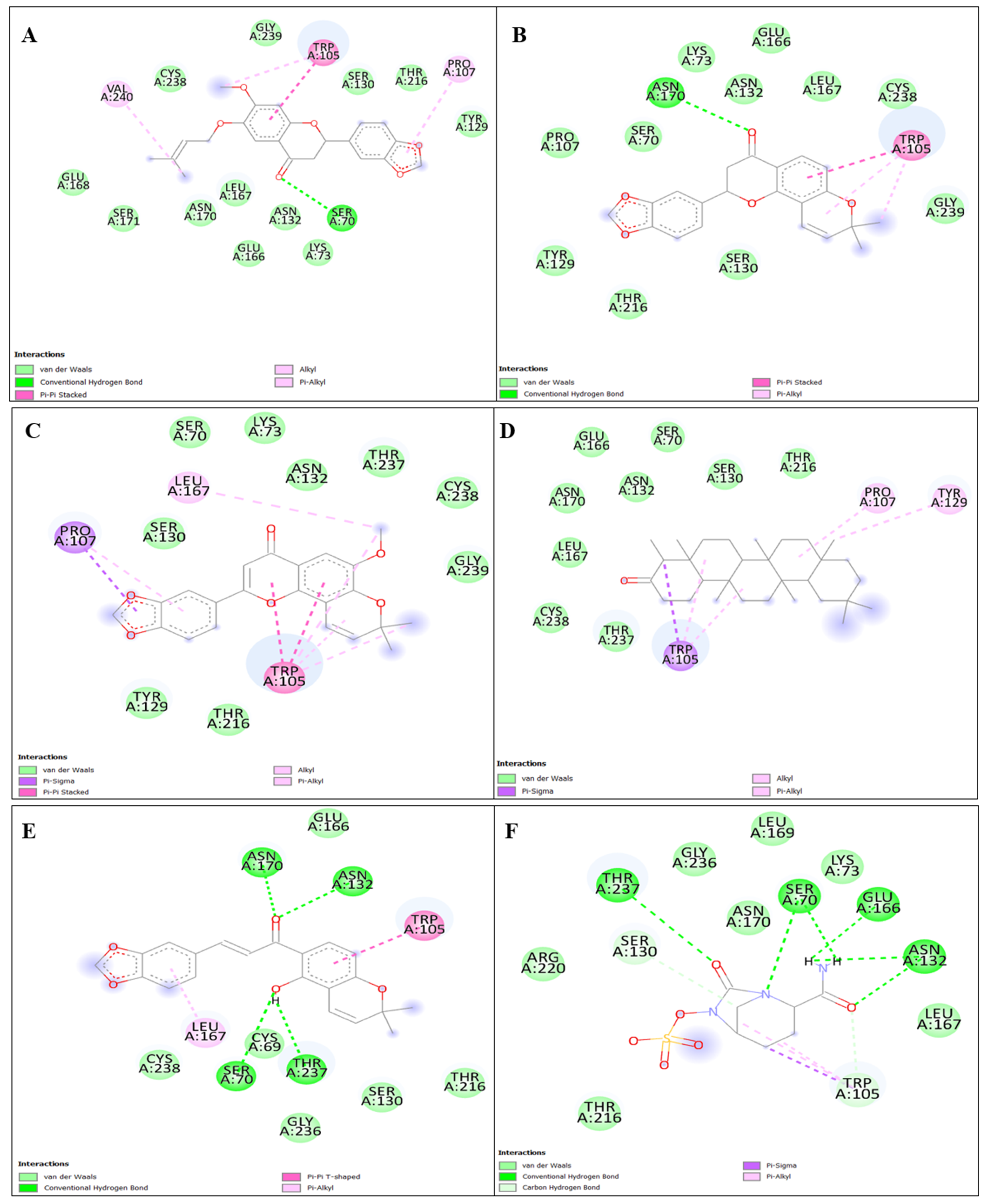

3.1.1. Binding Interaction Analysis

3.1.2. Reference Interaction Analysis (Avibactam)

3.2. ADMET Prediction

3.3. Molecular Dynamics Simulation

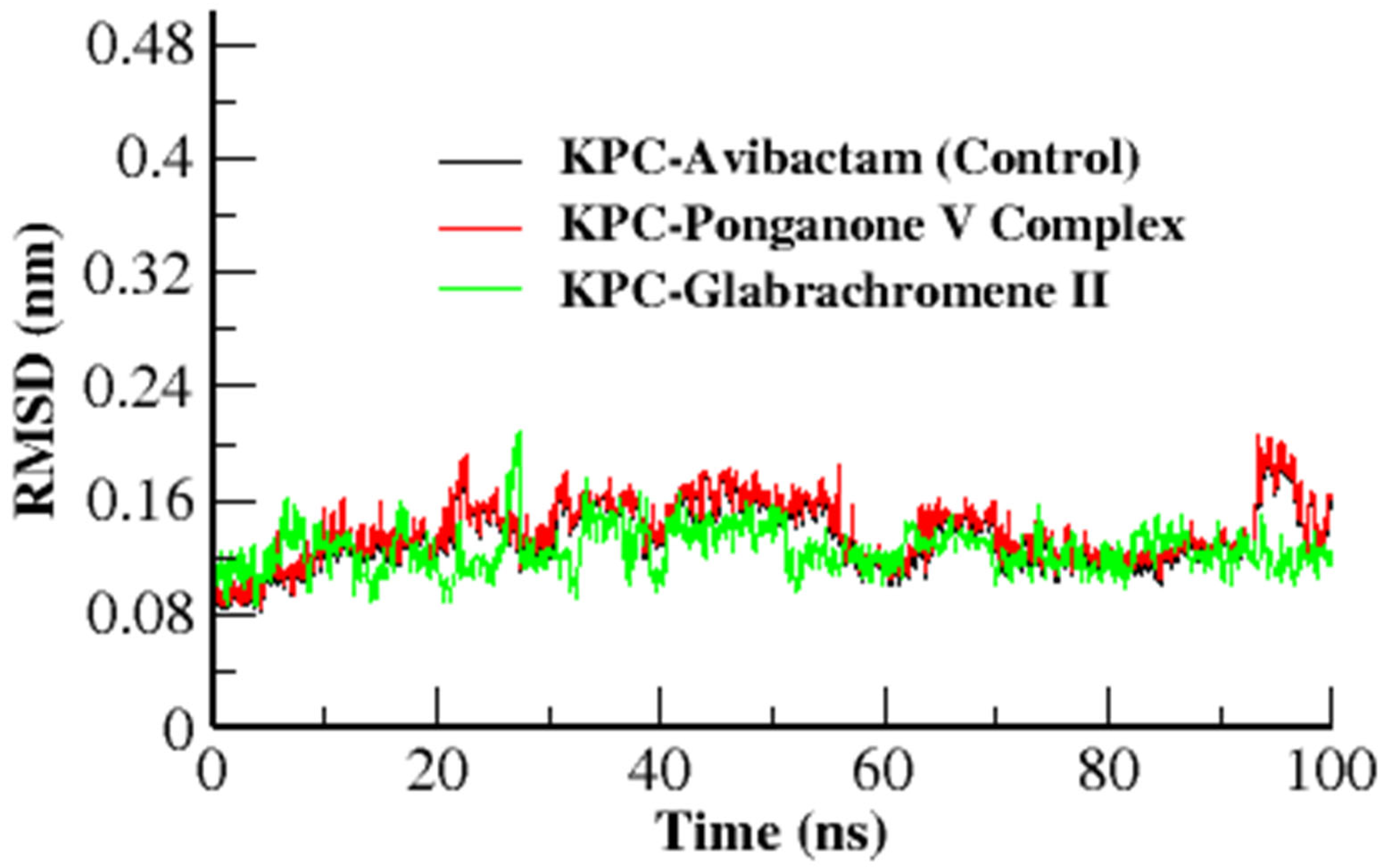

3.3.1. Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD)

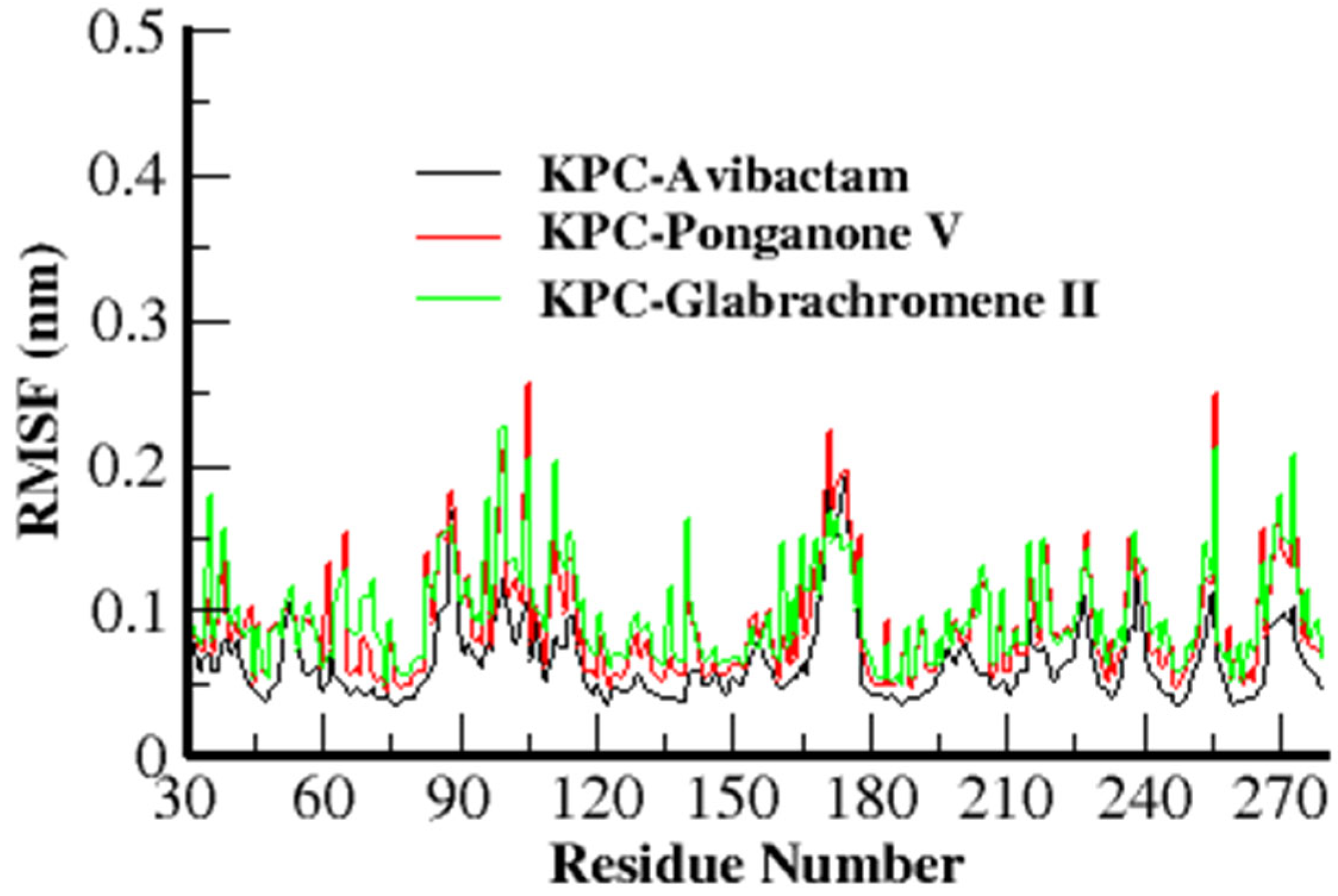

3.3.2. Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF)

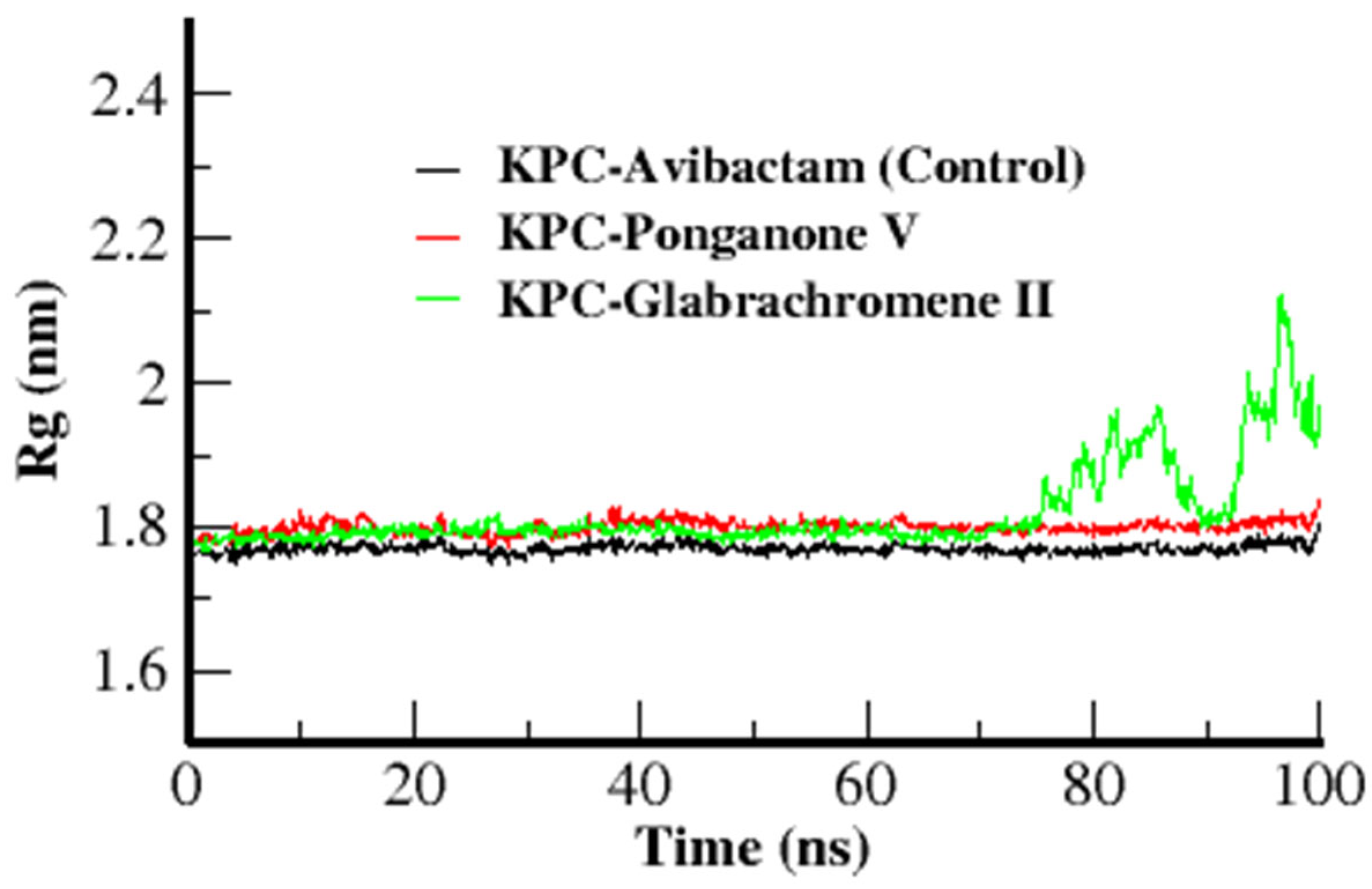

3.3.3. Radius of Gyration

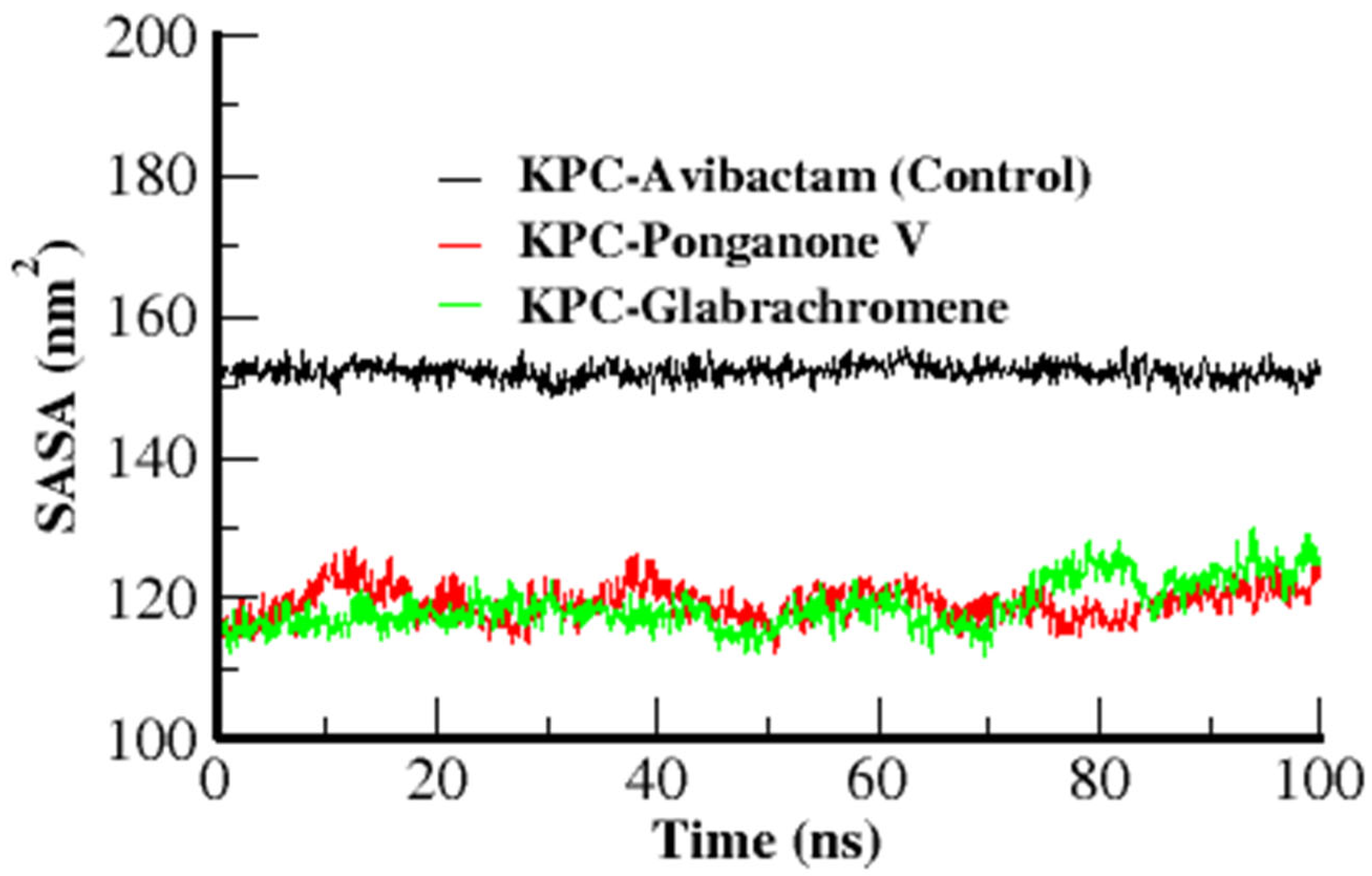

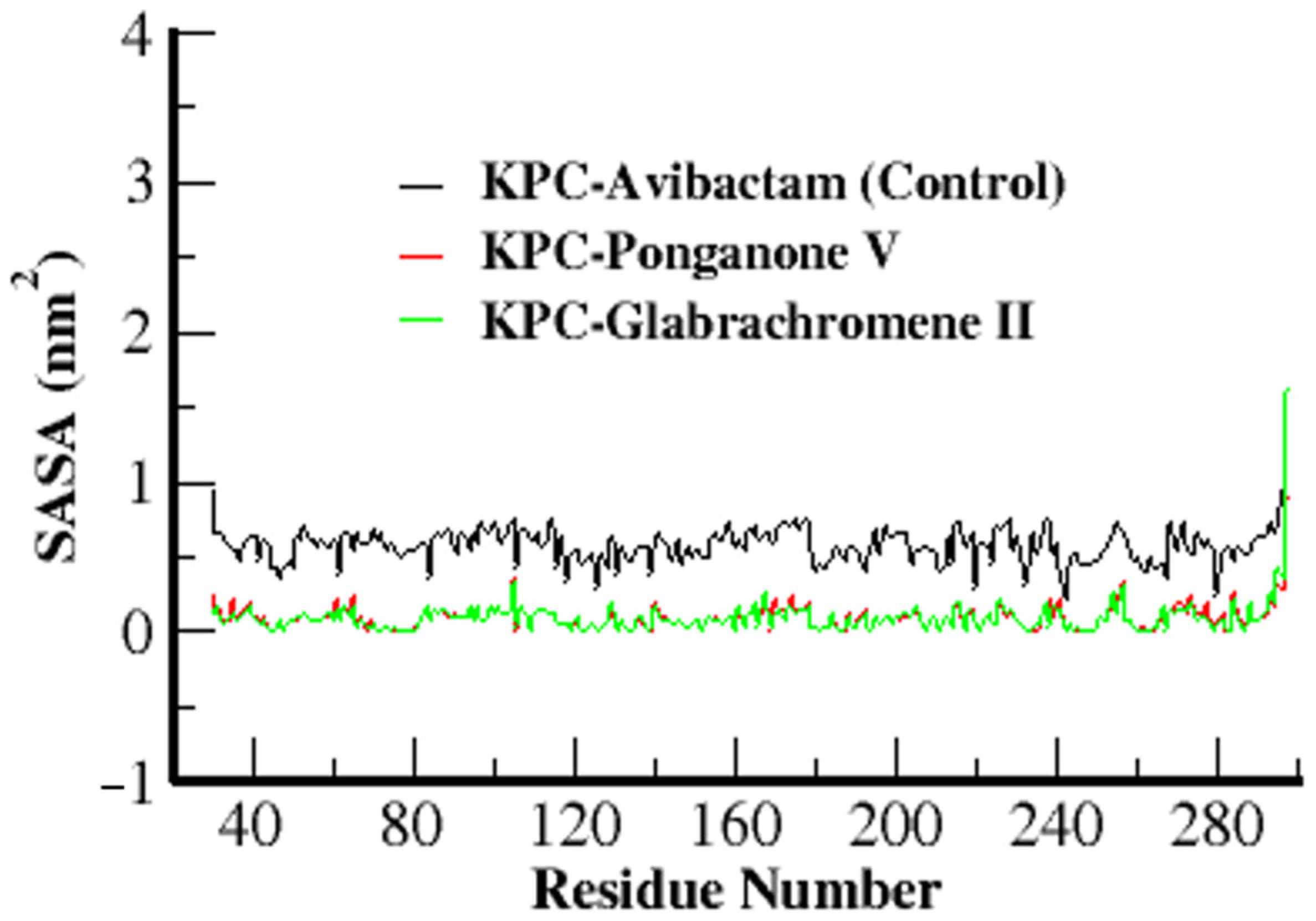

3.3.4. Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA)

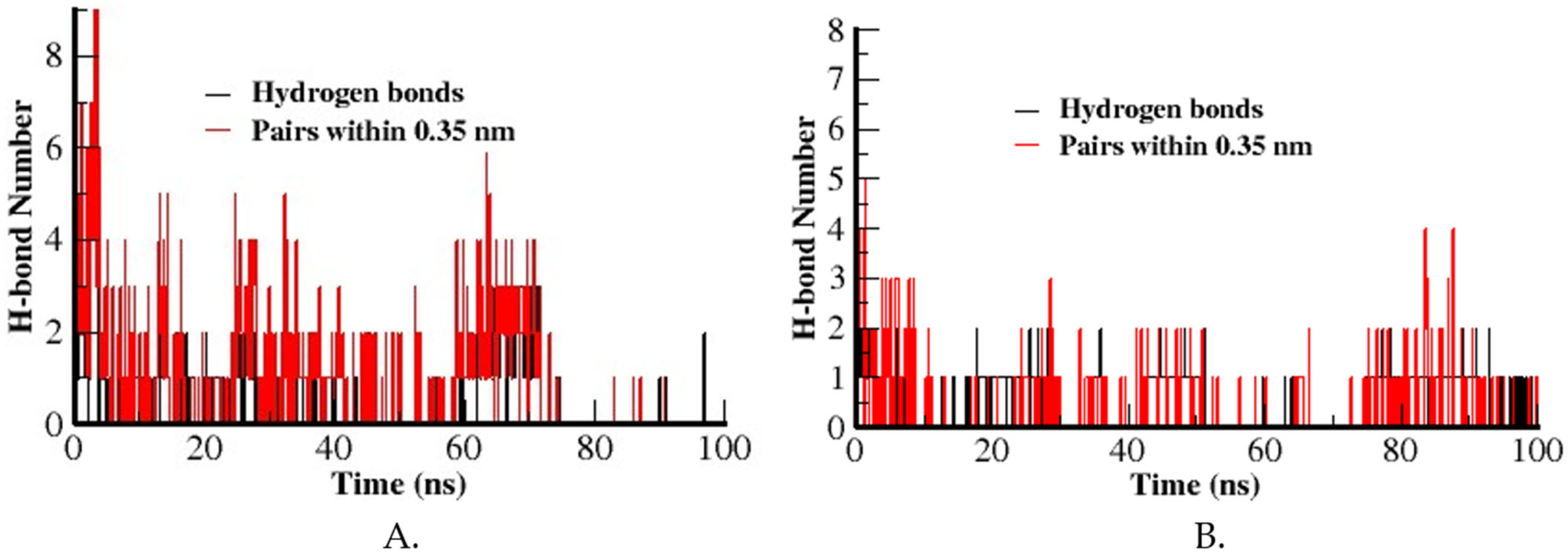

3.3.5. Hydrogen Bond

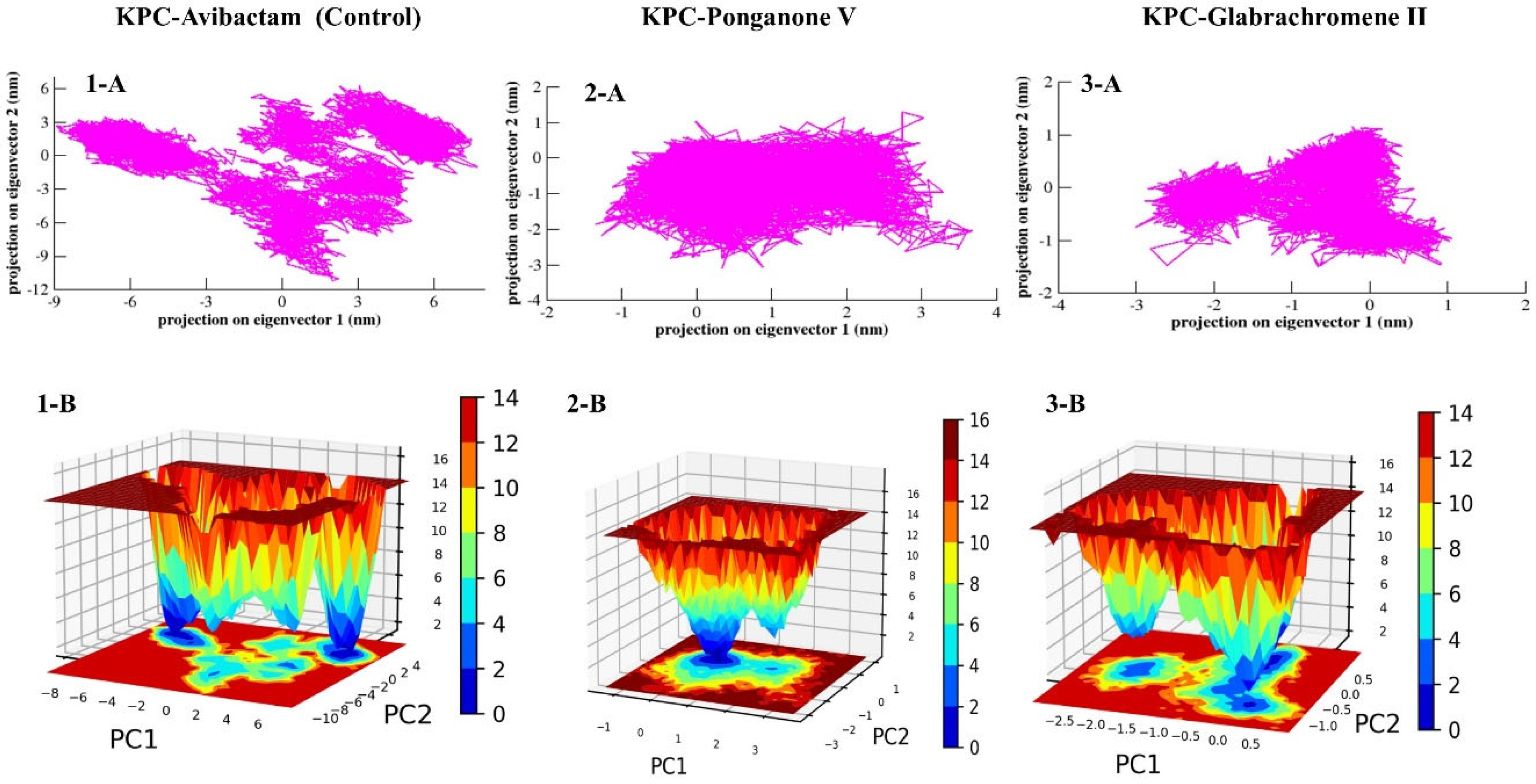

3.3.6. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Free Energy Landscape (FEL)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Olayiwola, J.O.; Ojo, D.A.; Balogun, S.A.; Ojo, O.E. Global Spread of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae: A Challenging Threat to the Treatment of Bacterial Diseases in Clinical Practice. Int. J. Res. Innov. Appl. Sci. 2021, 6, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, L.K.; Weinstein, R.A. The Epidemiology of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae: The Impact and Evolution of a Global Menace. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 215, S28–S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Sun, Q.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Shu, L.; Zhou, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhang, R.; et al. Rapid Increase in Prevalence of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) and Emergence of Colistin Resistance Gene Mcr-1 in CRE in a Hospital in Henan, China. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2018, 56, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pemberton, O.A.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y. Molecular Basis of Substrate Recognition and Product Release by the Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase (KPC-2). J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 3525–3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tooke, C.L.; Hinchliffe, P.; Bonomo, R.A.; Schofield, C.J.; Mulholland, A.J.; Spencer, J. Natural Variants Modify Klebsiella Pneumoniae Carbapenemase (KPC) Acyl–Enzyme Conformational Dynamics to Extend Antibiotic Resistance. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, W.; Bethel, C.R.; Thomson, J.M.; Bonomo, R.A.; Van Den Akker, F. Crystal Structure of KPC-2: Insights into Carbapenemase Activity in Class A β-Lactamases. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 5732–5740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munshi, R.; Salazar, W.; Taufiq, F.; Kauser, T.; Alam, M.; Pinargote, P. P-295. Risk Factors for Mortality in Patients with Klebsiella Pneumoniae Carbapenemase (KPC)-Producing Organisms Treated with Ceftazidime/Avibactam: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2025, 12, ofae631.498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschke, P.; Miczek, I.; Sambura, M.; Rosołowska-Żak, S.; Pałuchowska, J.; Szymkowicz, A. Effectiveness of Ceftazidime/Avibactam Treatment for Infections Caused by Klebsiella Pneumoniae Carbapenemase (KPC), a 30-Day Mortality Perspective. Comparison of Results with Control Groups Treated with Other Antibiotics. J. Educ. Health Sport 2024, 71, 49182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Shan, B.; Zhang, X.; Qu, F.; Jia, W.; Huang, B.; Yu, H.; Tang, Y.-W.; Chen, L.; Du, H. Reduced Ceftazidime-Avibactam Susceptibility in KPC-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae from Patients Without Ceftazidime-Avibactam Use History—A Multicenter Study in China. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaachouay, N.; Zidane, L. Plant-Derived Natural Products: A Source for Drug Discovery and Development. Drugs Drug Candidates 2024, 3, 184–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, Y.; Chokkalingam, D.; Gopinath, G.r.; Moses, A.c.; Thanikachalam, P.; Ms, P.; Bharathy, P. Plant-Based Phytochemicals as Antibiotic Alternatives for Gangrene: A Sustainable Approach to Infection Management. Sustain. Chem. Clim. Action 2025, 6, 100089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Muqarrabun, L.M.R.; Ahmat, N.; Ruzaina, S.A.S.; Ismail, N.H.; Sahidin, I. Medicinal Uses, Phytochemistry and Pharmacology of Pongamia pinnata (L.) Pierre: A Review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 150, 395–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satapathy, T.; Kumar, Y.; Pandey, R.K.; Shukla, S.S.; Bhardwaj, S.K.; Gidwani, B. A Review of the Medicinal Value and Chemical Composition of Flavonoids from Pongamia pinnata: Recent Work in Drug Advancement and Therapeutics. Curr. Drug Ther. 2025, 20, 517–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsha, T.L.; Tejaswini, K.S.; Nischith, S.S.; Rupesh Kumar, M.M.; Bharathi, D.R. Phytopharmaceutical and Pharmacological Aspects of “Pongamia pinnata”-a Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Health Care Bio. Sci. 2022, 3, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, M.M.; Kashid, N. Phytochemical Investigation and Antibacterial Activiy of Pongamia pinnata (L.) Against Some Multidrug Human Pathogens. Int. J. Res. Anal. Rev. 2018, 5, 743–752. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.; Meher, S.; Tiwari, S.; Bhadran, S. In Vitro Antimicrobial Activity and Phytochemical Analysis of Leaves, Seeds, Bark, Flowers of Pongamia pinnata (Linn. Pierre) Against Human Pathogens. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2021, 12, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inala, M.; Dayanand, C.; Sivaraj, N.; Beena, P.; Kutty, A. Antibacterial Activity of Flavonoids Extracted from Seeds of Pongamia pinnata Linn on Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus. Br. Microbiol. Res. J. 2015, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, A.; Khibech, O.; Benabbou, A.; Merzouki, M.; Bouhrim, M.; Al-Zharani, M.; Nasr, F.A.; Ahmed Qurtam, A.; Abadi, S.; Challioui, A.; et al. ADMET-Guided Docking and GROMACS Molecular Dynamics of Ziziphus Lotus Phytochemicals Uncover Mutation-Agnostic Allosteric Stabilisers of the KRAS Switch-I/II Groove. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, Y.; Koonyosying, P.; Srichairatanakool, S.; Ponpandian, L.N.; Kumaravelu, J.; Srichairatanakool, S. In Silico Molecular Docking and Dynamics Simulation Analysis of Potential Histone Lysine Methyl Transferase Inhibitors for Managing β-Thalassemia. Molecules 2023, 28, 7266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K, D.; Venugopal, S. Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamic Simulation Studies to Identify Potential Terpenes against Internalin A Protein of Listeria Monocytogenes. Front. Bioinform. 2024, 4, 1463750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chikhale, R.V.; Choudhary, R.; Eldesoky, G.E.; Kolpe, M.S.; Shinde, O.; Hossain, D. Generative AI, Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulations Assisted Identification of Novel Transcriptional Repressor EthR Inhibitors to Target Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Heliyon 2025, 11, e42593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, D.; Rathor, L.S.; Dwivedi, S.D.; Shah, K.; Chauhan, N.S.; Singh, M.R.; Singh, D. A Review on Molecular Docking as an Interpretative Tool for Molecular Targets in Disease Management. ASSAY Drug Dev. Technol. 2024, 22, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, H.; Barik, A.; Singh, Y.P.; Suresh, A.; Singh, L.; Singh, G.; Nayak, U.Y.; Dubey, V.K.; Modi, G. Molecular Docking, Binding Mode Analysis, Molecular Dynamics, and Prediction of ADMET/Toxicity Properties of Selective Potential Antiviral Agents against SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease: An Effort toward Drug Repurposing to Combat COVID-19. Mol. Divers. 2021, 25, 1905–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkhayar, K.; Haloui, R.; Daoui, O.; Elkhattabi, K.; Chtita, S.; Elkhattabi, S. In Silico Studies of 2-Aryloxy-1,4- Naphthoquinone Derivatives as Antibacterial Agents against Escherichia Coli Using 3D-QSAR, ADMET Properties, Molecular Docking, and Molecular Dynamics. Chem. Data Collect. 2023, 47, 101060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera—A Visualization System for Exploratory Research and Analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, A.; Chen, Y. Crystal Structure of KPC-2 with Compound 3: 6m7i. 2019. Available online: https://www.wwpdb.org/pdb?id=pdb_00006m7i (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Molavi, Z.; Razi, S.; Mirmotalebisohi, S.A.; Adibi, A.; Sameni, M.; Karami, F.; Niazi, V.; Niknam, Z.; Aliashrafi, M.; Taheri, M.; et al. Identification of FDA Approved Drugs against SARS-CoV-2 RNA Dependent RNA Polymerase (RdRp) and 3-Chymotrypsin-like Protease (3CLpro), Drug Repurposing Approach. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 138, 111544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, T.; Mathur, Y.; Hassan, M.I. InstaDock: A Single-Click Graphical User Interface for Molecular Docking-Based Virtual High-Throughput Screening. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, bbaa279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, D.E.V.; Blundell, T.L.; Ascher, D.B. pkCSM: Predicting Small-Molecule Pharmacokinetic and Toxicity Properties Using Graph-Based Signatures. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 4066–4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nada, H.; Elkamhawy, A.; Lee, K. Identification of 1H-Purine-2,6-Dione Derivative as a Potential SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease Inhibitor: Molecular Docking, Dynamic Simulations, and Energy Calculations. PeerJ 2022, 10, e14120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS: High Performance Molecular Simulations through Multi-Level Parallelism from Laptops to Supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1–2, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boattini, M.; Bianco, G.; Comini, S.; Costa, C.; Gaibani, P. In Vivo Development of Resistance to Novel β-Lactam/β-Lactamase Inhibitor Combinations in KPC-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae Infections: A Case Series. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2024, 43, 2407–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiseo, G.; Falcone, M.; Leonildi, A.; Giordano, C.; Barnini, S.; Arcari, G.; Carattoli, A.; Menichetti, F. Meropenem-Vaborbactam as Salvage Therapy for Ceftazidime-Avibactam-, Cefiderocol-Resistant ST-512 Klebsiella pneumoniae–Producing KPC-31, a D179Y Variant of KPC-3. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2021, 8, ofab141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eiamphungporn, W.; Schaduangrat, N.; Malik, A.A.; Nantasenamat, C. Tackling the Antibiotic Resistance Caused by Class A β-Lactamases through the Use of β-Lactamase Inhibitory Protein. IJMS 2018, 19, 2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, N.G.; Chow, D.-C.; Palzkill, T. BLIP-II Is a Highly Potent Inhibitor of Klebsiella Pneumoniae Carbapenemase (KPC-2). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 3398–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ligand Code | Ligand Name | Binding Free Energy (kcal/mol) | pKi | Ligand Efficiency (kcal/mol/non-H atom) | Torsional Energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMPHY003033 | Ponganone V | −9 | 6.6 | 0.3214 | 1.5565 |

| IMPHY000058 | Ovalichromene B | −8.8 | 6.45 | 0.3385 | 0.3113 |

| IMPHY004719 | Isopongachromene | −8.8 | 6.45 | 0.3143 | 0.6226 |

| IMPHY011688 | Friedelin | −8.7 | 6.38 | 0.2806 | 0 |

| IMPHY006225 | Glabrachromene II | −8.6 | 6.31 | 0.3308 | 1.2452 |

| IMPHY001489 | Ovalifolin | −8.4 | 6.16 | 0.3231 | 1.2452 |

| IMPHY014969 | kaempferol 7-O-glucoside | −8.4 | 6.16 | 0.2625 | 3.4243 |

| IMPHY012756 | Quercimeritrin | −8.4 | 6.16 | 0.2545 | 3.7356 |

| IMPHY011471 | Lupenone | −8.3 | 6.09 | 0.2677 | 0.3113 |

| IMPHY008838 | Gamatin | −8.3 | 6.09 | 0.332 | 0.6226 |

| CID 9835049 | Avibactam (Control) | −6.3 | 4.62 | 0.3706 | 1.2452 |

| Property | Model Name | Unit | Ponganone V | Ovalichromene B | Isopongachromene | Friedelin | Glabrachromene II |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted Value | |||||||

| Absorption | Water solubility | Numeric (log mol/L) | −5.733 | −4.823 | −4.429 | −5.514 | −4.578 |

| Caco2 permeability | Numeric (log Papp in 10−6 cm/s) | 1.3 | 1.485 | 0.592 | 1.266 | 0.78 | |

| Intestinal absorption (human) | Numeric (% Absorbed) | 95.538 | 96.351 | 96.828 | 98.736 | 94.204 | |

| Skin Permeability | Numeric (log Kp) | −2.742 | −2.798 | −2.655 | −2.605 | −2.978 | |

| P-glycoprotein substrate | Categorical (Yes/No) | No | No | No | No | No | |

| P-glycoprotein I inhibitor | Categorical (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| P-glycoprotein II inhibitor | Categorical (Yes/No) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Distribution | VDss (human) | Numeric (log L/kg) | −0.165 | 0.058 | 0.166 | −0.272 | 0.071 |

| Fraction unbound (human) | Numeric (Fu) | 0 | 0.025 | 0.087 | 0 | 0 | |

| BBB permeability | Numeric (log BB) | −0.751 | −0.454 | −0.61 | 0.72 | −0.448 | |

| CNS permeability | Numeric (log PS) | −2.792 | −1.721 | −1.926 | −1.555 | −1.891 | |

| Metabolism | CYP2D6 substrate | Categorical (Yes/No) | No | No | No | No | No |

| CYP3A4 substrate | Categorical (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| CYP1A2 inhibitior | Categorical (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | |

| CYP2C19 inhibitior | Categorical (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | |

| CYP2C9 inhibitior | Categorical (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | |

| CYP2D6 inhibitior | Categorical (Yes/No) | No | No | No | No | No | |

| CYP3A4 inhibitior | Categorical (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Excreation | Total Clearance | Numeric (log ml/min/kg) | 0.021 | −0.196 | 0.394 | −0.04 | −0.141 |

| Renal OCT2 substrate | Categorical (Yes/No) | No | No | Yes | No | No | |

| Toxicity | AMES toxicity | Categorical (Yes/No) | No | No | No | No | No |

| Max. tolerated dose (human) | Numeric (log mg/kg/day) | 0.663 | 0.193 | −0.074 | −0.213 | −0.405 | |

| hERG I inhibitor | Categorical (Yes/No) | No | No | No | No | No | |

| hERG II inhibitor | Categorical (Yes/No) | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Oral Rat Acute Toxicity (LD50) | Numeric (mol/kg) | 2.775 | 2.722 | 2.668 | 2.64 | 2.455 | |

| Oral Rat Chronic Toxicity (LOAEL) | Numeric (log mg/kg_bw/day) | 1.596 | 1.79 | 1.236 | 0.909 | 1.598 | |

| Hepatotoxicity | Categorical (Yes/No) | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Skin Sensitisation | Categorical (Yes/No) | No | No | No | No | No | |

| T.Pyriformis toxicity | Numeric (log ug/L) | 0.396 | 0.457 | 0.349 | 0.3 | 0.643 | |

| Minnow toxicity | Numeric (log mM) | 0.193 | 0.831 | 0.029 | −2.384 | −0.081 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jangid, H.; Chopra, C.; Wani, A.K. Structure-Based Identification of Ponganone V from Pongamia pinnata as a Potential KPC-2 β-Lactamase Inhibitor: Insights from Docking, ADMET, and Molecular Dynamics. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 16, 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16120262

Jangid H, Chopra C, Wani AK. Structure-Based Identification of Ponganone V from Pongamia pinnata as a Potential KPC-2 β-Lactamase Inhibitor: Insights from Docking, ADMET, and Molecular Dynamics. Microbiology Research. 2025; 16(12):262. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16120262

Chicago/Turabian StyleJangid, Himanshu, Chirag Chopra, and Atif Khurshid Wani. 2025. "Structure-Based Identification of Ponganone V from Pongamia pinnata as a Potential KPC-2 β-Lactamase Inhibitor: Insights from Docking, ADMET, and Molecular Dynamics" Microbiology Research 16, no. 12: 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16120262

APA StyleJangid, H., Chopra, C., & Wani, A. K. (2025). Structure-Based Identification of Ponganone V from Pongamia pinnata as a Potential KPC-2 β-Lactamase Inhibitor: Insights from Docking, ADMET, and Molecular Dynamics. Microbiology Research, 16(12), 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16120262