Exploratory Dietary Approaches for Drug-Resistant Epilepsy Beyond Standard Ketogenic Diet and Fish Oil: A Systematic Review of Preliminary Clinical Evidence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Protocol and Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Population: Humans of any age with a confirmed diagnosis of epilepsy.

- Intervention: Any dietary intervention other than a standard ketogenic diet (KD), modified Atkins diet, KD modified only by adjusting carbohydrate portions, or isolated fish oil/omega-3 fatty acid supplementation.

- Comparator: No intervention, placebo, usual diet, or an active dietary intervention.

- Outcomes: At least one outcome related to seizure control (e.g., seizure frequency, responder rate, e.g., ≥50% reduction in seizures], seizure freedom).

- Study Design: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomized studies of interventions (NRSIs), including quasi-experimental and pre-post studies.

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Assessment

2.5. Data Synthesis

3. Results

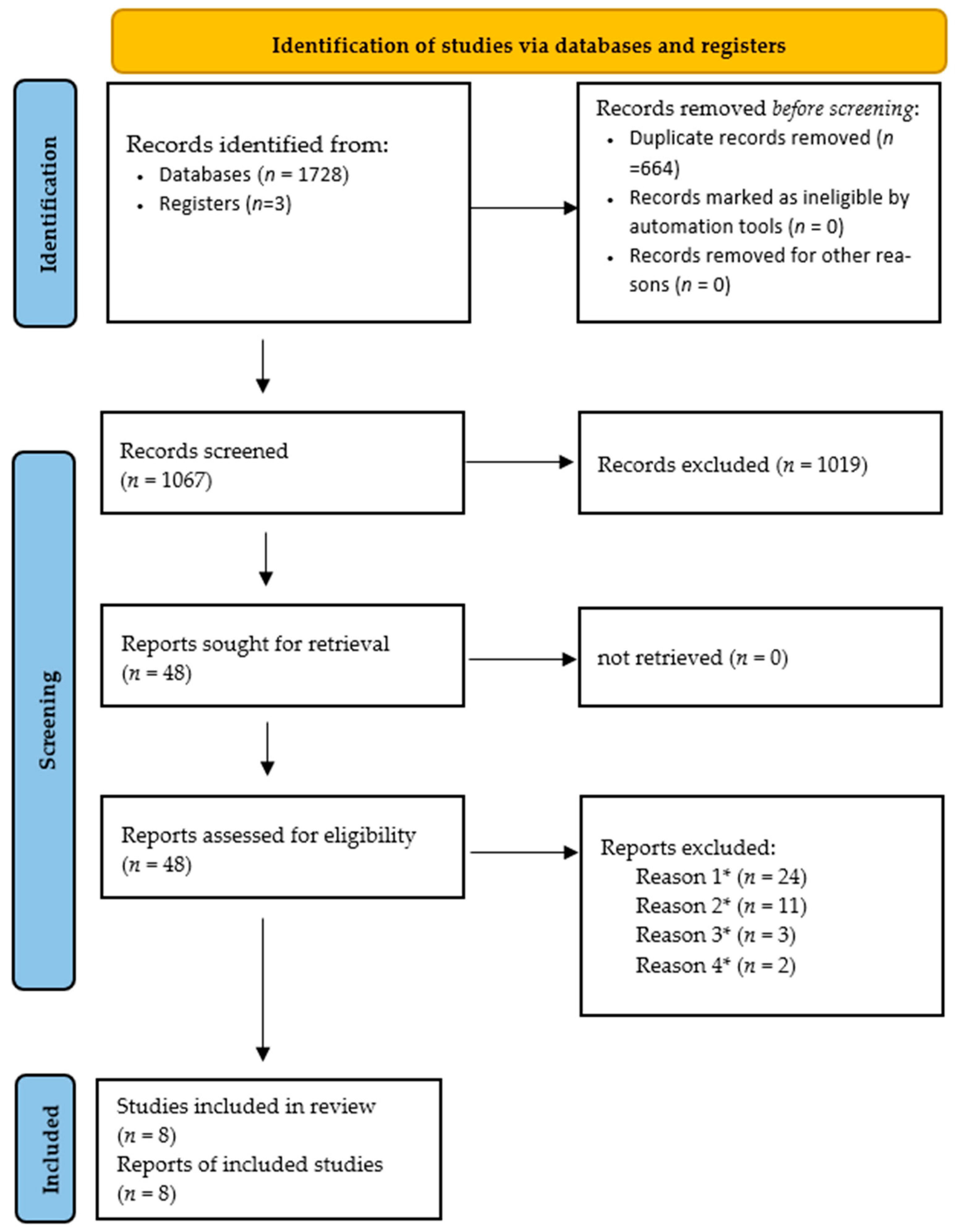

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

3.2. Synthesis of Results (Qualitative Analysis of the 8 Included Studies)

- BCAA Supplementation (Evangeliou 2009 [31]): This study (n = 17) investigated BCAAs as an adjunct to KD. While 18% of patients achieved seizure freedom, the pre-post design makes it impossible to distinguish the BCAA effect from the underlying KD efficacy.

- MCT-based KD (Neal 2009 [30]): This high-quality RCT (n = 145) compared MCT-based KD directly to a classical KD. Finding no statistically significant difference in seizure frequency, it suggests that MCT protocols are an effective alternative but do not provide a superior seizure-control advantage.

- Olive Oil-Based KD (Guzel 2019 [24]): This represents the largest study in our review (n = 389). It reported an 83.1% responder rate at 12 months. While encouraging, the lack of a control group and a 25.7% dropout rate limit the practical conclusion. The study suggests that Mediterranean-style fat sources may improve the long-term sustainability of the KD, but efficacy cannot be definitively attributed to olive oil without head-to-head RCT data against standard vegetable oils.

- Probiotics (Lactobacillus/Bifidobacterium) (Gómez-Eguílaz 2018 [11]): This pilot study (n = 45) observed a 28.9% responder rate. While it establishes the gut–brain axis as a viable clinical target, the open-label design and self-reported seizure diaries introduce a high risk of bias, particularly regarding the placebo effect.

- Synbiotics (Shariatmadari 2024 [26]): This quasi-experimental study (n = 30) reported a significant mean seizure reduction (p = 0.001). However, the 8-week duration is insufficient to determine long-term efficacy or potential shifts in the gut microbiome.

- Supplemental MCT (Rasmussen 2023 [28]): This pilot study (n = 9) added MCT oil to a regular diet. While a 42% seizure reduction was reported, the sample size is critically low, essentially serving as a case series.

- Gluten-Free Diet (Bashiri 2016 [29]): The 86% seizure freedom rate reported in this small NRSI (n = 7) is striking. However, all participants had confirmed celiac disease. The clinical takeaway is that GFD is highly effective only when systemic gluten sensitivity is the primary driver.

- Low Glutamate Diet (Sarlo 2023 [27]): This non-blinded RCT (n = 33) is the only trial to specifically test a restrictive diet against a control group. The negative result (p = 0.57) suggests that dietary glutamate restriction may not be an effective monotherapy for pediatric DRE, despite its mechanistic popularity.

4. Discussion

5. Interpretation of the Results

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, L.; Li, M.; Wang, Z.; Li, Q. Global trends and burden of idiopathic epilepsy: Regional and gender differences from 1990 to 2021 and future outlook. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2025, 44, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh, P.; Nazarbaghi, S. The prevalence of drug-resistant-epilepsy and its associated factors in patients with epilepsy. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2022, 213, 107086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, S.; Nathan, J.; Godhia, M. Efficacy and tolerability of classical and polyunsaturated fatty acids ketogenic diet in controlling paediatric refractory epilepsy-A randomized study. Epilepsy Res. 2024, 204, 107395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, P.; Singh, S.C.; Ramadass, B. Drug resistant epilepsy and ketogenic diet: A narrative review of mechanisms of action. World Neurosurg. X 2024, 22, 100328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Marugan, L.; Rutsch, A.; Kaindl, A.M.; Ronchi, F. The impact of microbiota and ketogenic diet interventions in the management of drug-resistant epilepsy. Acta Physiol. 2024, 240, e14104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sondhi, V.; Agarwala, A.; Pandey, R.M.; Chakrabarty, B.; Jauhari, P.; Lodha, R.; Toteja, G.S.; Sharma, S.; Paul, V.K.; Kossoff, E.; et al. Efficacy of Ketogenic Diet, Modified Atkins Diet, and Low Glycemic Index Therapy Diet Among Children With Drug-Resistant Epilepsy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, 944–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGiorgio, C.M.; Miller, P.R.; Harper, R.; Gornbein, J.; Schrader, L.; Soss, J.; Meymandi, S. Fish oil (n-3 fatty acids) in drug resistant epilepsy: A randomised placebo-controlled crossover study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2015, 86, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutarelli, A.; Nogueira, A.; Felix, N.; Godoi, A.; Dagostin, C.S.; Castro, L.H.M.; Telles, J.P.M. Modified Atkins diet for drug-resistant epilepsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Seizure Eur. J. Epilepsy 2023, 112, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, N.; Madaan, P.; Kandoth, N.; Bansal, D.; Sahu, J.K. Efficacy and Safety of Dietary Therapies for Childhood Drug-Resistant Epilepsy: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2023, 177, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-McGill, K.J.; Bresnahan, R.; Levy, R.G.; Cooper, P.N. Ketogenic diets for drug-resistant epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Eguílaz, M.; Ramón-Trapero, J.; Pérez-Martínez, L.; Blanco, J. The beneficial effect of probiotics as a supplementary treatment in drug-resistant epilepsy: A pilot study. Benef. Microbes 2018, 9, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egger, J.; Carter, C.; Soothill, J.; Wilson, J. Oligoantigenic diet treatment of children with epilepsy and migraine. J. Pediatr. 1989, 114, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, Y.-N.; Li, L.; Hu, S.-H.; Yang, Y.-X.; Ma, Z.-Z.; Huang, L.; An, Y.-P.; Yuan, Y.-Y.; Lin, Y.; Xu, W.; et al. Ketogenic diet-produced β-hydroxybutyric acid accumulates brain GABA and increases GABA/glutamate ratio to inhibit epilepsy. Cell Discov. 2024, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes Neri, L.d.C.L.; Guglielmetti, M.; Fiorini, S.; Pasca, L.; Zanaboni, M.P.; de Giorgis, V.; Tagliabue, A.; Ferraris, C. Adherence to ketogenic dietary therapies in epilepsy: A systematic review of literature. Nutr. Res. 2024, 126, 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhanna, A.; Mhanna, M.; Beran, A.; Al-Chalabi, M.; Aladamat, N.; Mahfooz, N. Modified Atkins diet versus ketogenic diet in children with drug-resistant epilepsy: A meta-analysis of comparative studies. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2022, 51, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlin, M.; Hjelte, L.; Nilsson, S.; Åmark, P. Plasma phospholipid fatty acids are influenced by a ketogenic diet enriched with n-3 fatty acids in children with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2007, 73, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clanton, R.M.; Wu, G.; Akabani, G.; Aramayo, R. Control of seizures by ketogenic diet-induced modulation of metabolic pathways. Amino Acids 2017, 49, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erecińska, M.; Nelson, D.; Daikhin, Y.; Yudkoff, M. Regulation of GABA Level in Rat Brain Synaptosomes: Fluxes Through Enzymes of the GABA Shunt and Effects of Glutamate, Calcium, and Ketone Bodies. J. Neurochem. 1996, 67, 2325–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melø, T.M.; Nehlig, A.; Sonnewald, U. Neuronal–glial interactions in rats fed a ketogenic diet. Neurochem. Int. 2006, 48, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartzkroin, P.A. Mechanisms underlying the anti-epileptic efficacy of the ketogenic diet. Epilepsy Res. 1999, 37, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, N.M.; Madsen, K.K.; Schousboe, A.; White, H.S. Glutamate and GABA synthesis, release, transport and metabolism as targets for seizure control. Neurochem. Int. 2012, 61, 546–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khayat, H.; Wakad, A.; Marzook, Z.A.; Awadalla, M.M. Polyunsaturated fatty acids in children with idiopathic intractable epilepsy: Serum levels and therapeutic response. J. Pediatr. Neurol. 2010, 8, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, B.; Koepp, M.; Holmes, J.; Hamilton, G.; Yuen, A. A 31-phosphorus neurospectroscopy study of ω-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid intervention with eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid in patients with chronic refractory epilepsy. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2007, 77, 105–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzel, O.; Uysal, U.; Arslan, N. Efficacy and tolerability of olive oil-based ketogenic diet in children with drug-resistant epilepsy: A single center experience from Turkey. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2019, 23, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohouli, M.H.; Razmpoosh, E.; Zarrati, M.; Jaberzadeh, S. The effect of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation on seizure frequency in individuals with epilepsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Neurosci. 2022, 25, 2421–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariatmadari, F.; Motaghi, A.; Shabestari, A.A.; Hashemi, S.M.; Almasi-Hashiani, A. The effect of synbiotics in the treatment of drug-resistant epilepsy and the parental burden of caregivers: A single-arm pretest-posttest trial. BMC Pediatr. 2024, 24, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarlo, G.L.; Kao, A.; Holton, K.F. Investigation of the low glutamate diet as an adjunct treatment for pediatric epilepsy: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Seizure 2023, 106, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, E.; Patel, V.; Tideman, S.; Frech, R.; Frigerio, R.; Narayanan, J. Efficacy of supplemental MCT oil on seizure reduction of adult drug-resistant epilepsy—A single-center open-label pilot study. Nutr. Neurosci. 2023, 26, 535–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashiri, H.; Afshari, D.; Babaei, N.; Ghadami, M.R. Celiac Disease and Epilepsy: The Effect of Gluten-Free Diet on Seizure Control. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2016, 25, 751–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, E.G.; Chaffe, H.; Schwartz, R.H.; Lawson, M.S.; Edwards, N.; Fitzsimmons, G.; Whitney, A.; Cross, J.H. A randomized trial of classical and medium-chain triglyceride ketogenic diets in the treatment of childhood epilepsy. Epilepsia 2009, 50, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evangeliou, A.; Spilioti, M.; Doulioglou, V.; Kalaidopoulou, P.; Ilias, A.; Skarpalezou, A.; Katsanika, I.; Kalamitsou, S.; Vasilaki, K.; Chatziioanidis, I.; et al. Branched chain amino acids as adjunctive therapy to ketogenic diet in epilepsy: Pilot study and hypothesis. J. Child. Neurol. 2009, 24, 1268–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanquet, L.; Serra, D.; Marrinhas, C.; Almeida, A. Exploring Gut Microbiota-Targeted Therapies for Canine Idiopathic Epilepsy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Huang, C.; Xiong, S. Gut microbiota as a potential therapeutic target for children with cerebral palsy and epilepsy. Brain Dev. 2025, 47, 104286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, F.; Nishikata, N.; Nishimura, M.; Nagao, K.; Kawamura, M. Leucine-Enriched Essential Amino Acids Enhance the Antiseizure Effects of the Ketogenic Diet in Rats. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 637288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruenbaum, S.E.; Dhaher, R.; Rapuano, A.B.; Zaveri, H.P.; Tang, A.; de Lanerolle, N.; Eid, T. Effects of Branched-Chain Amino Acid Supplementation on Spontaneous Seizures and Neuronal Viability in a Model of Mesial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. J. Neurosurg. Anesthesiol. 2019, 31, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufour, F.; Nalecz, A.K.; Nalecz, M.J.; Nehlig, A. Modulation of pentylenetetrazol-induced seizure activity by branched-chain amino acids and α-ketoisocaproate. Brain Res. 1999, 815, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maciejak, P.; Szyndler, J.; Turzyńska, D.; Sobolewska, A.; Kołosowska, K.; Krząścik, P.; Płaźnik, A. Is the interaction between fatty acids and tryptophan responsible for the efficacy of a ketogenic diet in epilepsy? The new hypothesis of action. Neuroscience 2016, 313, 130–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengah, D.S.N.A.P.; Holmes, G.K.T.; Wills, A.J. The Prevalence of Epilepsy in Patients with Celiac Disease. Epilepsia 2004, 45, 1291–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fois, A.; Vascotto, M.; Di Bartolo, R.M.; Di Marco, V. Celiac disease and epilepsy in pediatric patients. Child’s Nerv. Syst. 1994, 10, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julian Higgins, J.T. (Ed.) Cochrane, Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Wiley Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gruenbaum, S.E.; Chen, E.C.; Sandhu, M.R.S.; Deshpande, K.; Dhaher, R.; Hersey, D.; Eid, T. Branched-Chain Amino Acids and Seizures: A Systematic Review of the Literature. CNS Drugs 2019, 33, 755–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.; DiSilvio, B.; Fernstrom, M.H.; Fernstrom, J.D. Oral branched-chain amino acid supplements that reduce brain serotonin during exercise in rats also lower brain catecholamines. Amino Acids 2013, 45, 1133–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, G.; Adachi, N.; Liu, K.; Motoki, A.; Mitsuyo, T.; Nagaro, T.; Arai, T. Recovery of Brain Dopamine Metabolism by Branched-chain Amino Acids in Rats with Acute Hepatic Failure. J. Neurosurg. Anesthesiol. 2007, 19, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzam, R.; Azar, N.J. Marked Seizure Reduction After MCT Supplementation. Case Rep. Neurol. Med. 2013, 2013, 809151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicerale, S.; Lucas, L.J.; Keast, R.S.J. Antimicrobial, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory phenolic activities in extra virgin olive oil. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012, 23, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogani, P.; Galli, C.; Villa, M.; Visioli, F. Postprandial anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of extra virgin olive oil. Atherosclerosis 2007, 190, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Jiao, Y.; Han, C.; Li, Y.; Zou, W.; Liu, J. Drug-Resistant Epilepsy and Gut-Brain Axis: An Overview of a New Strategy for Treatment. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024, 61, 10023–10040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, S.; Yu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, S.; Jia, M.; Chen, T.; Zhang, X. Gut microbiota modulates neurotransmitter and gut-brain signaling. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 287, 127858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study ID | Setting and Study Design | Intervention Details | Duration (Months) | Sample Size (N) | Gender (%Male) | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evangeliou et al., 2009 [31] | Single-arm, pre-post intervention | BCAA powder (up to 20 g/d) + KD | 6–24 | 17 | N/A | 2–7 |

| Neal et al., 2009 [30] | Randomized trial | MCT-based ketogenic diet | 3, 6, 12 | 145 | 52.40% | 2–16 |

| Guzel et al., 2019 [24] | Single-center, prospective study | Olive oil-based KD | 1–12 | 389 | 51.90% | 0.5–18 |

| Gómez-Eguílaz et al., 2018 [11] | Single-arm, pre-post intervention | Probiotics (8 species, 4 × 1011/d) | 4 | 45 | 53.30% | ≥18 |

| Shariatmadari et al., 2024 [26] | Pre-post quasi-experimental study | Synbiotics | 2 | 30 | 60% | 1–15 |

| Rasmussen et al., 2023 [28] | Single-center open-label intervention | Supplemental MCT oil to regular diet | 3 | 9 | 33.30% | 24–63 |

| Bashiri et al., 2016 [29] | Single-arm, pre-post intervention | Gluten-Free Diet | 5 | 7 | 57% | 26–38 |

| Sarlo et al., 2023 [27] | Non-blinded, parallel, randomized clinical trial | Low glutamate diet | 1 | 33 | 54.50% | 2–21 |

| Study ID | Intervention | Primary Outcomes | Synthesis of Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evangeliou et al., 2009 [31] | BCAA + KD | Seizure reduction | 18% (3/17) seizure-free; 29% (5/17) had 50–90% seizure reduction vs. KD baseline. |

| Neal et al., 2009 [30] | MCT + KD | Seizure frequency | No significant differences vs. classical KD (p > 0.05 at 3, 6, or 12 months). |

| Guzel et al., 2019 [24] | Olive oil-KD | Responder rates (≥50% seizure reduction) | 83.1% responder rate at 12 months; 43.1% seizure-free |

| Gómez-Eguílaz et al., 2018 [11] | Probiotics | Responder rate (≥50% seizure reduction) | 28.9% (13/15) achieved ≥50% seizure reduction |

| Shariatmadari et al., 2024 [26] | Synbiotics | Seizure frequency | Significant decrease (Pre: 15.83, Post: 12.73, p = 0.001). |

| Rasmussen et al., 2023 [28] | MCT | Seizure frequency | 42% reduction in seizures (p < 0.0001). |

| Bashiri et al., 2016 [29] | GFD (for Celiac) | Seizure freedom | 86% (6/7) achieved seizure freedom. |

| Sarlo et al., 2023 [27] | Low Glutamate | Seizure frequency | Non-Seizure improvements (p = 0.57). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Meng, X.; Zhou, K. Exploratory Dietary Approaches for Drug-Resistant Epilepsy Beyond Standard Ketogenic Diet and Fish Oil: A Systematic Review of Preliminary Clinical Evidence. Neurol. Int. 2026, 18, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint18010009

Meng X, Zhou K. Exploratory Dietary Approaches for Drug-Resistant Epilepsy Beyond Standard Ketogenic Diet and Fish Oil: A Systematic Review of Preliminary Clinical Evidence. Neurology International. 2026; 18(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint18010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeng, Xianghong, and Kequan Zhou. 2026. "Exploratory Dietary Approaches for Drug-Resistant Epilepsy Beyond Standard Ketogenic Diet and Fish Oil: A Systematic Review of Preliminary Clinical Evidence" Neurology International 18, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint18010009

APA StyleMeng, X., & Zhou, K. (2026). Exploratory Dietary Approaches for Drug-Resistant Epilepsy Beyond Standard Ketogenic Diet and Fish Oil: A Systematic Review of Preliminary Clinical Evidence. Neurology International, 18(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint18010009