Systematic Review: Proteomics-Driven Multi-Omics Integration for Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology and Precision Medicine

Abstract

1. Introduction

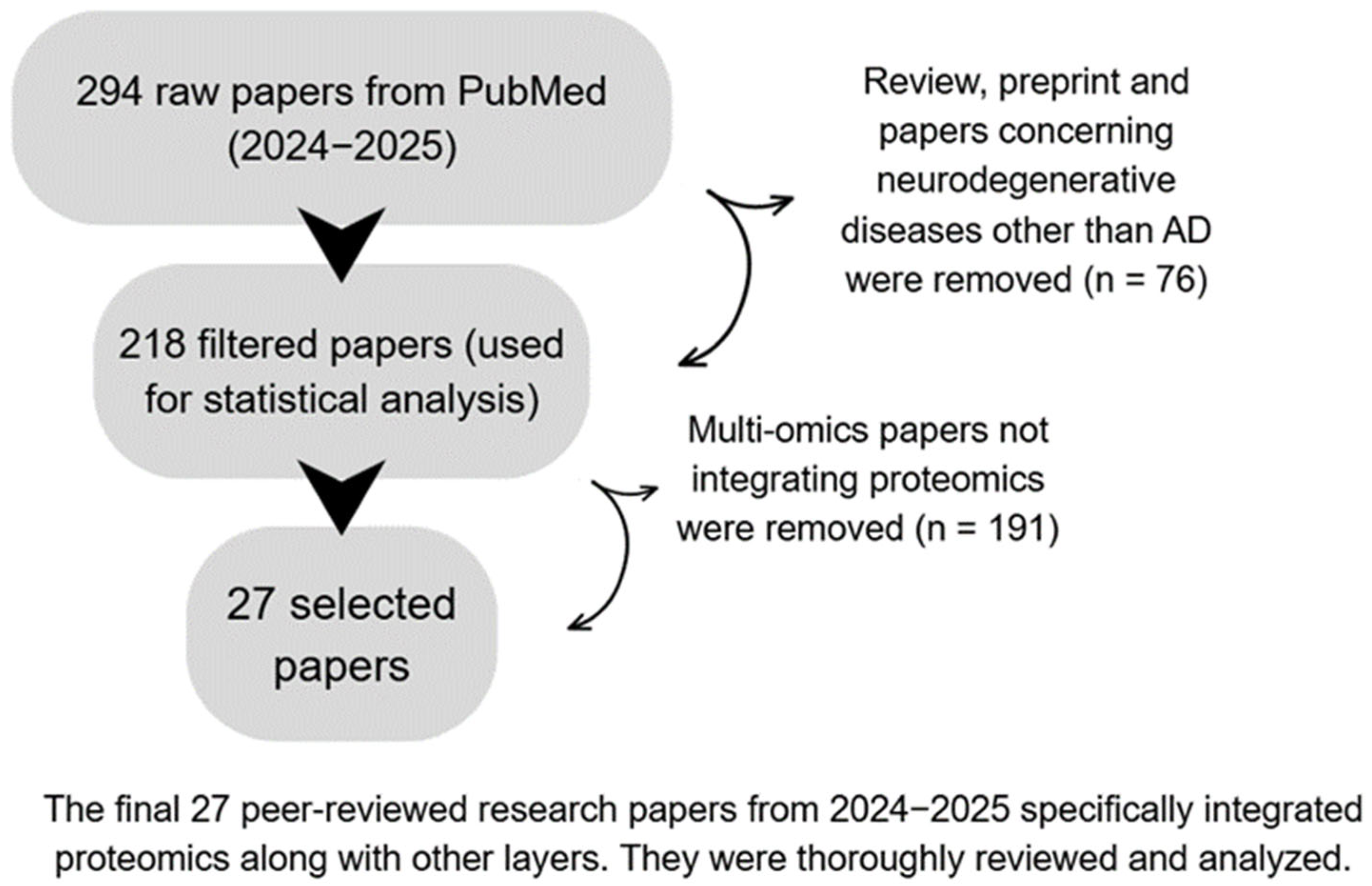

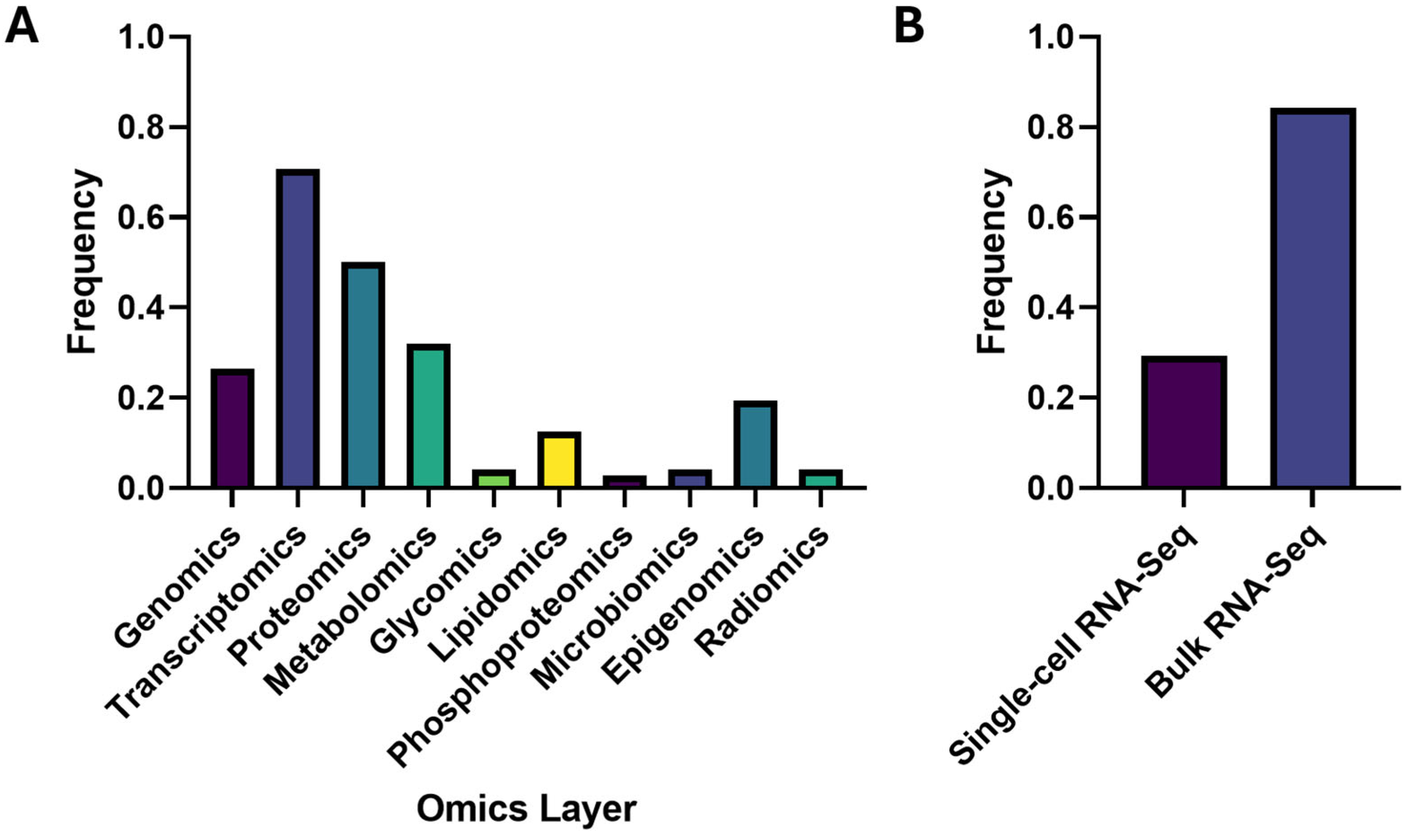

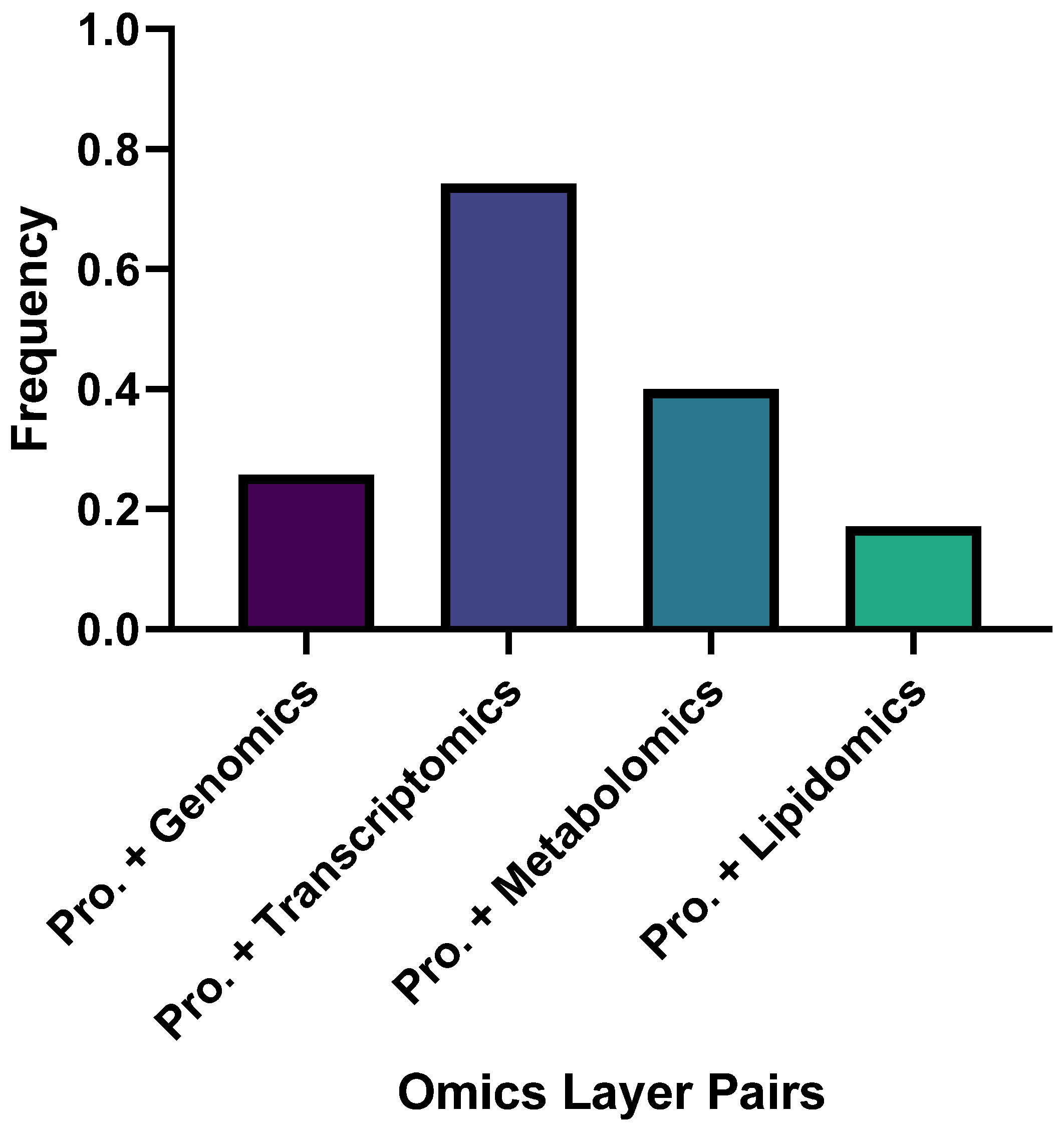

2. Methods—Search Strategy and Study Selection

3. Results

3.1. Four Major Research Pillars in Proteomics-Anchored Multi-Omics Studies

3.1.1. Causal and Computational Integration

3.1.2. Fluid Biomarkers and Clinical Translation

3.1.3. Brain Tissue and Spatial Mechanisms

3.1.4. Models, Comorbidity and Resources

4. Summary of the Most Common AD Mechanisms

4.1. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Metabolic Dysregulation

4.2. Synaptic Dysfunction

4.3. Neuroinflammation and Immune–Lipid Activation

4.4. Proteostasis and Delayed Protein Turnover

4.5. Tau Phosphorylation and Proteoform-Specific Pathology

5. Discussion and Future Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| NDs | Neurodegenerative diseases |

| MCI | Mild cognitive impairment |

| CN | Cognitively normal |

| NC | Normal control |

| ADAS-Cog | Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| ADNI | Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative |

| ROSMAP/ROS/MAP | Religious Orders Study/Memory and Aging Project |

| MSDD | Mount Sinai Brain Bank |

| ARIC | Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities |

| EMIF-AD | European Medical Information Framework-Alzheimer’s Disease |

| AMP-AD | Accelerating Medicines Partnership-Alzheimer’s Disease |

| ADRC | Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center |

| SAND | SAND cohort (study name as cited) |

| ACC | Anterior cingulate cortex |

| PCC | Posterior cingulate cortex |

| PHG | Parahippocampal gyrus |

| FP | Frontal pole |

| IFG | Inferior frontal gyrus |

| STG | Superior temporal gyrus |

| TCX | Temporal cortex |

| DLPFC | Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

| BM36 | Brodmann area 36 |

| CAA | Cerebral amyloid angiopathy |

| Aβ | Amyloid-β |

| pTau181 | Phosphorylated tau at threonine 181 |

| PHFtau | Paired helical filament tau |

| APP | Amyloid precursor protein |

| APOE (ε4) | Apolipoprotein E (ε4 allele) |

| PSEN1/PSEN2 | Presenilin-1/Presenilin-2 |

| TREM2 | Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 |

| MAPT | Microtubule-associated protein tau |

| GFAP | Glial fibrillary acidic protein |

| NEFL | Neurofilament light |

| NPTX2 | Neuronal pentraxin 2 |

| ABCA1 | ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 |

| PBXIP1 | Pre-B-cell leukemia homeobox interacting protein 1 |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| TMEM106B | Transmembrane protein 106B |

| HLA-B | Human leukocyte antigen-B |

| CLU | Clusterin |

| LDLR | Low-density lipoprotein receptor |

| ACE | Angiotensin-converting enzyme |

| PTPMT1 | Protein-tyrosine phosphatase mitochondrial 1 |

| IL-17C/IL-18 | Interleukin-17C/Interleukin-18 |

| HGF | Hepatocyte growth factor |

| OSM | Oncostatin M |

| GABA | Gamma-aminobutyric acid |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| ncRNAs | Non-coding RNAs |

| miRNA/miRNAs | MicroRNA(s) (e.g., miR-33, miR-133b) |

| piRNAs | PIWI-interacting RNAs |

| siRNAs | Small interfering RNAs |

| circRNAs | Circular RNAs |

| CpG | Cytosine–phosphate–guanine dinucleotide |

| 5hmC | 5-hydroxymethylcytosine |

| GWAS | Genome-wide association study |

| QTL | Quantitative trait locus |

| eQTL/pQTL/mQTL | Expression/protein/methylation QTL |

| TWAS | Transcriptome-wide association study |

| MR | Mendelian randomization |

| MR-Egger | MR-Egger regression |

| MR-PRESSO | Mendelian Randomization Pleiotropy RESidual Sum and Outlier |

| DIABLO | Data Integration Analysis for Biomarker discovery using Latent cOmponents |

| PLS | Partial least squares |

| MOFA/MOFA+ | Multi-Omics Factor Analysis/MOFA Plus |

| iCluster | Integrative clustering framework |

| WGCNA | Weighted gene co-expression network analysis |

| PPI | Protein–protein interaction |

| ATN | Amyloid/Tau/Neurodegeneration (biomarker framework) |

| RNA-seq | RNA sequencing |

| ChIP-seq | Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing |

| hMe-Seal | Hydroxymethylation selective chemical labeling (for 5hmC) |

| LC-MS/MS | Ultra-performance LC–MS/MS |

| DDA/DIA | Data-dependent/data-independent acquisition |

| SRM/PRM | Selected/parallel reaction monitoring |

| MALDI-MSI | Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry imaging |

| TMT-MS/TMT | Tandem mass tag mass spectrometry/Tandem mass tags |

| STORM | Stochastic Optical Reconstruction Microscopy |

| OrbiSIMS | Orbitrap Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry |

| CRISPR/Cas9 | Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats/CRISPR-associated protein 9 |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| Olink | Olink proximity-extension assay platform |

| SomaScan | SomaLogic aptamer-based proteomics platform |

| GNNRAI | Graph Neural Network-derived Representation Alignment and Integration |

| MOGONET | Multi-Omics Graph cOnvolutional NETwork |

| MoFNet | (Model name; multi-omics network) |

| SNARE | Soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor Attachment protein REceptor (complex) |

| EV/HS-EVs | Extracellular vesicle/High-speed-isolated EVs |

| TRS | Target Risk Score |

| AAV-AD | Adeno-associated virus-based AD model |

| 3xTg-AD | Triple-transgenic Alzheimer’s disease mouse |

| T2DM | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| BA/LA | Black American/Latin American |

| ML | Machine learning |

| SVM | Support vector machine |

| RF | Random forest |

| k-NN | k-nearest neighbor |

| XGBoost | eXtreme Gradient Boosting |

References

- Gadhave, D.G.; Sugandhi, V.V.; Jha, S.K.; Nangare, S.N.; Gupta, G.; Singh, S.K.; Dua, K.; Cho, H.; Hansbro, P.M.; Paudel, K.R. Neurodegenerative disorders: Mechanisms of degeneration and therapeutic approaches with their clinical relevance. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 99, 102357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugger, B.N.; Dickson, D.W. Pathology of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2017, 9, a028035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2025 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2025, 21, 332–384. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, E.C.B.; Carter, E.K.; Dammer, E.B.; Duong, D.M.; Gerasimov, E.S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Betarbet, R.; Ping, L.; Yin, L.; et al. Large-scale deep multi-layer analysis of Alzheimer’s disease brain reveals strong proteomic disease-related changes not observed at the RNA level. Nat. Neurosci. 2022, 25, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrup, K. The case for rejecting the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 794–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cauwenberghe, C.; Van Broeckhoven, C.; Sleegers, K. The genetic landscape of Alzheimer disease: Clinical implications and perspectives. Genet Med. 2016, 18, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riscado, M.; Baptista, B.; Sousa, F. New RNA-Based Breakthroughs in Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnosis and Therapeutics. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kauwe, J.S.K.; Cruchaga, C.; Karch, C.M.; Sadler, B.; Lee, M.; Mayo, K.; Latu, W.; Su’a, M.; Fagan, A.M.; Holtzman, D.M.; et al. Fine mapping of genetic variants in BIN1, CLU, CR1 and PICALM for association with cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e15918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, P.C.; Yu, K.; Dey, K.K.; Yarbro, J.M.; Han, X.; Lutz, B.M.; Rao, S.; et al. Deep Multilayer Brain Proteomics Identifies Molecular Networks in Alzheimer’s Disease Progression. Neuron 2020, 105, 975–991.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellenguez, C.; Küçükali, F.; Jansen, I.E.; Kleineidam, L.; Moreno-Grau, S.; Amin, N.; Naj, A.C.; Campos-Martin, R.; Grenier-Boley, B.; Andrade, V.; et al. New insights into the genetic etiology of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Nat. Genet. 2022, 54, 412–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguzzoli Heberle, B.; Fox, K.L.; Lobraico Libermann, L.; Ronchetti Martins Xavier, S.; Tarnowski Dallarosa, G.; Carolina Santos, R.; Fardo, D.W.; Wendt Viola, T.; Ebbert, M.T. Systematic review and meta-analysis of bulk RNAseq studies in human Alzheimer’s disease brain tissue. Alzheimers Dement. 2025, 21, e70025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathys, H.; Davila-Velderrain, J.; Peng, Z.; Gao, F.; Mohammadi, S.; Young, J.Z.; Menon, M.; He, L.; Abdurrob, F.; Jiang, X.; et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 2019, 570, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarbro, J.M.; Shrestha, H.K.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zaman, M.; Chu, M.; Wang, X.; Yu, G.; Peng, J. Proteomic landscape of Alzheimer’s disease: Emerging technologies, advances and insights (2021–2025). Mol. Neurodegener. 2025, 20, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.; Vanderwall, D.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Poudel, S.; Wang, H.; Dey, K.K.; Chen, P.C.; Yang, K.; Peng, J. Proteomic landscape of Alzheimer’s Disease: Novel insights into pathogenesis and biomarker discovery. Mol. Neurodegener. 2021, 16, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyfried, N.T.; Dammer, E.B.; Swarup, V.; Nandakumar, D.; Duong, D.M.; Yin, L.; Deng, Q.; Nguyen, T.; Hales, C.M.; Wingo, T.; et al. A Multi-network Approach Identifies Protein-Specific Co-expression in Asymptomatic and Symptomatic Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell Syst. 2017, 4, 60–72.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.B.; Maranville, J.C.; Peters, J.E.; Stacey, D.; Staley, J.R.; Blackshaw, J.; Burgess, S.; Jiang, T.; Paige, E.; Surendran, P.; et al. Genomic atlas of the human plasma proteome. Nature 2018, 558, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasin, Y.; Seldin, M.; Lusis, A. Multi-omics approaches to disease. Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, I.; Verma, S.; Kumar, S.; Jere, A.; Anamika, K. Multi-omics Data Integration, Interpretation, and Its Application. Bioinform. Biol. Insights 2020, 14, 1177932219899051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleshchevnikov, V.; Shmatko, A.; Dann, E.; Aivazidis, A.; King, H.W.; Li, T.; Elmentaite, R.; Lomakin, A.; Kedlian, V.; Gayoso, A.; et al. Cell2location maps fine-grained cell types in spatial transcriptomics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Xu, J.; Green, R.; Wretlind, A.; Homann, J.; Buckley, N.J.; Tijms, B.M.; Vos, S.J.; Lill, C.M.; Kate, M.T.; et al. Multiomics profiling of human plasma and cerebrospinal fluid reveals ATN-derived networks and highlights causal links in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2023, 19, 3350–3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, H.; Cammann, D.; Cummings, J.L.; Dong, X.; Chen, J. Biomarker identification for Alzheimer’s disease through integration of comprehensive Mendelian randomization and proteomics data. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-X.; Wei, M.; Wang, H.-R.; Hu, Y.-Z.; Sun, H.-M.; Jia, J.-J. Mitochondrial dysfunction gene expression, DNA methylation, and inflammatory cytokines interaction activate Alzheimer’s disease: A multi-omics Mendelian randomization study. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Gong, W.; Liu, X.; Mo, Q.; Shen, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, S.; Yuan, Z. Multi-Omics Integration Analysis Pinpoint Proteins Influencing Brain Structure and Function: Toward Drug Targets and Neuroimaging Biomarkers for Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathy, R.K.; Frohock, Z.; Wang, H.; Cary, G.A.; Keegan, S.; Carter, G.W.; Li, Y. Effective integration of multi-omics with prior knowledge to identify biomarkers via explainable graph neural networks. npj Syst. Biol. Appl. 2025, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cary, G.A.; Wiley, J.C.; Gockley, J.; Keegan, S.; Amirtha Ganesh, S.S.; Heath, L.; Butler, R.R., III; Mangravite, L.M.; Logsdon, B.A.; Longo, F.M.; et al. Genetic and multi-omic risk assessment of Alzheimer’s disease implicates core associated biological domains. Alzheimers Dement. 2024, 10, e12461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, K.; Zhou, W.; Kong, S. Exploring biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease based on multi-omics and Mendelian randomisation analysis. Ann. Hum. Biol. 2024, 51, 2415035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.F.; Penwell, T.; Chen, Y.-H.; Koehler, A.; Wu, R.; Akhtar, S.N.; Lu, Q. G-Protein Signaling in Alzheimer’s Disease: Spatial Expression Validation of Semi-supervised Deep Learning-Based Computational Framework. J. Neurosci. 2024, 44, e0587242024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Raj, Y.; Varathan, P.; He, B.; Yu, M.; Nho, K.; Salama, P.; Saykin, A.J.; Yan, J. Deep Trans-Omic Network Fusion for Molecular Mechanism of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2024, 99, 715–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Fan, Z.; Li, Q.; Chen, Y. PPIA-coExp: Discovering Context-Specific Biomarkers Based on Protein-Protein Interactions, Co-Expression Networks, and Expression Data. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Jin, H.; Yulug, B.; Altay, O.; Li, X.; Hanoglu, L.; Cankaya, S.; Coskun, E.; Idil, E.; Nogaylar, R.; et al. Multi-omics analysis reveals the key factors involved in the severity of the Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2024, 16, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, T.; Li, N.; Chao, Y.; Gao, S.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, S.; Zhao, L.; Dong, X. A multi-omics study to monitor senescence-associated secretory phenotypes of Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2024, 11, 1310–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Pascual, A.; Naccache, T.; Xu, J.; Hooshmand, K.; Wretlind, A.; Gabrielli, M.; Lombardo, M.T.; Shi, L.; Buckley, N.J.; Tijms, B.M.; et al. Paired plasma lipidomics and proteomics analysis in the conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 176, 108588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- François, M.; Pascovici, D.; Wang, Y.; Vu, T.; Liu, J.W.; Beale, D.; Hor, M.; Hecker, J.; Faunt, J.; Maddison, J.; et al. Saliva Proteome, Metabolome and Microbiome Signatures for Detection of Alzheimer’s Disease. Metabolites 2024, 14, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souchet, B.; Michaïl, A.; Heuillet, M.; Dupuy-Gayral, A.; Haudebourg, E.; Pech, C.; Berthemy, A.; Autelitano, F.; Billoir, B.; Domoto-Reilly, K.; et al. Multiomics Blood-Based Biomarkers Predict Alzheimer’s Predementia with High Specificity in a Multicentric Cohort Study. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2024, 11, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Gu, T.; Gao, C.; Miao, G.; Palma-Gudiel, H.; Yu, L.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Lim, J.; et al. Brain 5-hydroxymethylcytosine alterations are associated with Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abyadeh, M.; Kaya, A. Multiomics from Alzheimer’s Brains and Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Identifies Therapeutic Potential of Specific Subpopulations to Target Mitochondrial Proteostasis. J. Cent. Nerv. Syst. Dis. 2025, 17, 11795735251336302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eteleeb, A.M.; Novotny, B.C.; Tarraga, C.S.; Sohn, C.; Dhungel, E.; Brase, L.; Nallapu, A.; Buss, J.; Farias, F.; Bergmann, K.; et al. Brain high-throughput multi-omics data reveal molecular heterogeneity in Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS Biol. 2024, 22, e3002607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyama, Y.; Nirasawa, T.; Morishima, M.; Saito, Y.; Irie, K.; Murayama, S.; Ikegawa, M. Integrated Spatial Multi-Omics Study of Postmortem Brains of Alzheimer’s Disease. Acta Histochem. Cytochem. 2024, 57, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, X.; Jia, X.; Sun, B.; Xu, S.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Z. Integrative multi-omics analysis reveals the critical role of the PBXIP1 gene in Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Cell 2024, 23, e14044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.-W.; Park, Y.H.; Bice, P.J.; Bennett, D.A.; Kim, S.; Saykin, A.J.; Nho, K. miR-133b as a potential regulator of a synaptic NPTX2 protein in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2024, 11, 2799–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarbro, J.M.; Han, X.; Dasgupta, A.; Yang, K.; Liu, D.; Shrestha, H.K.; Zaman, M.; Wang, Z.; Yu, K.; Lee, D.G.; et al. Human and mouse proteomics reveals the shared pathways in Alzheimer’s disease and delayed protein turnover in the amyloidome. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, D.; Yamashita, T.; Kosugi, Y. Multi-Omics Analysis of Hippocampus in Rats Administered Trimethyltin Chloride. Neurotox. Res. 2025, 43, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, J.S.; Heath, L.; Linden, A.V.; Allen, M.; Lopes, K.D.; Seifar, F.; Wang, E.; Ma, Y.; Poehlman, W.L.; Quicksall, Z.S.; et al. Bridging the gap: Multi-omics profiling of brain tissue in Alzheimer’s disease and older controls in multi-ethnic populations. Alzheimers Dement. 2024, 20, 7174–7192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, M.; Wijeratne, H.R.S.; Kim, B.; Philtjens, S.; You, Y.; Lee, D.H.; Gutierrez, D.A.; Sharify, D.; Wells, M.; Perez-Cardelo, M.; et al. Deletion of miR-33, a regulator of the ABCA1-APOE pathway, ameliorates neuropathological phenotypes in APP/PS1 mice. Alzheimers Dement. 2024, 20, 7805–7818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D.P.Q.; Jallow, A.W.; Lin, Y.-F.; Lin, Y.-F. Exploring the Potential Role of Oligodendrocyte-Associated PIP4K2A in Alzheimer’s Disease Complicated with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus via Multi-Omic Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.C.B.; Ho, K.; Yu, G.-Q.; Das, M.; Sanchez, P.E.; Djukic, B.; Lopez, I.; Yu, X.; Gill, M.; Zhang, W.; et al. Behavioral and neural network abnormalities in human APP transgenic mice resemble those of APP knock-in mice and are modulated by familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations but not by inhibition of BACE1. Mol. Neurodegener. 2020, 15, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higginbotham, L.; Ping, L.; Dammer, E.B.; Duong, D.M.; Zhou, M.; Gearing, M.; Hurst, C.; Glass, J.D.; Factor, S.A.; Johnson, E.C.; et al. Integrated proteomics reveals brain-based cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in asymptomatic and symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaz9360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichet Binette, A.; Gaiteri, C.; Wennström, M.; Kumar, A.; Hristovska, I.; Spotorno, N.; Salvadó, G.; Strandberg, O.; Mathys, H.; Tsai, L.H.; et al. Proteomic changes in Alzheimer’s disease associated with progressive Aβ plaque and tau tangle pathologies. Nat. Neurosci. 2024, 27, 1880–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porzig, R.; Singer, D.; Hoffmann, R. Epitope mapping of mAbs AT8 and Tau5 directed against hyperphosphorylated regions of the human tau protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 358, 644–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Ende, E.L.; In ‘t Veld, S.G.; Hanskamp, I.; Van Der Lee, S.; Dijkstra, J.I.; Hok-A-Hin, Y.S.; Blujdea, E.R.; Van Swieten, J.C.; Irwin, D.J.; Chen-Plotkin, A.; et al. CSF proteomics in autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease highlights parallels with sporadic disease. Brain 2023, 146, 4495–4507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikegawa, M.; Kakuda, N.; Miyasaka, T.; Toyama, Y.; Nirasawa, T.; Minta, K.; Hanrieder, J. Mass Spectrometry Imaging in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Review of Pathological Mechanisms. Brain Connect. 2023, 13, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doecke, J.D.; Bellomo, G.; Vermunt, L.; Alcolea, D.; Halbgebauer, S.; in ‘t Veld, S.; Mattsson-Carlgren, N.; Veverova, K.; Fowler, C.J.; Boonkamp, L.; et al. Diagnostic performance of plasma Aβ42/40 ratio, p-tau181, GFAP, and NfL along the continuum of Alzheimer’s disease and non-AD dementias: An international multi-center study. Alzheimers Dement. 2025, 21, e14573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, G.; Valletta, M.; Rizzuto, D.; Xia, X.; Qiu, C.; Orsini, N.; Dale, M.; Andersson, S.; Fredolini, C.; Winblad, B.; et al. Blood-based biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease and incident dementia in the community. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 2027–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mammeri, N.; Dregni, A.J.; Duan, P.; Hong, M. Structures of AT8 and PHF1 phosphomimetic tau. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2316175121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barthélemy, N.R.; Saef, B.; Li, Y.; Gordon, B.A.; He, Y.; Horie, K.; Stomrud, E.; Salvadó, G.; Janelidze, S.; Sato, C.; et al. CSF tau phosphorylation occupancies at T217 and T205 represent improved biomarkers of amyloid and tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Aging 2023, 3, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, T.; Moreira, P.I.; Cardoso, S. Current advances in mitochondrial targeted interventions in Alzheimer’s disease. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, K.R.; Combs, B.; Richards, C.; Grabinski, T.; Alhadidy, M.M.; Kanaan, N.M. Phosphomimetics at Ser199/Ser202/Thr205 in Tau Impairs Axonal Transport in Rat Hippocampal Neurons. Mol. Neurobiol. 2023, 60, 3423–3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koussounadis, A.; Langdon, S.P.; Um, I.H.; Harrison, D.J.; Smith, V.A. Genome-wide correlation between mRNA and protein in a xenograft model. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argelaguet, R.; Velten, B.; Arnol, D.; Dietrich, S.; Zenz, T.; Marioni, J.C.; Buettner, F.; Huber, W.; Stegle, O. Multi-Omics Factor Analysis—A framework for unsupervised integration of multi-omics data sets. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2018, 14, e8124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2008, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dong, J.M.; Zhong, H. Systematic Review: Proteomics-Driven Multi-Omics Integration for Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology and Precision Medicine. Neurol. Int. 2025, 17, 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint17120197

Dong JM, Zhong H. Systematic Review: Proteomics-Driven Multi-Omics Integration for Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology and Precision Medicine. Neurology International. 2025; 17(12):197. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint17120197

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Jonathan Mingsong, and Huan Zhong. 2025. "Systematic Review: Proteomics-Driven Multi-Omics Integration for Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology and Precision Medicine" Neurology International 17, no. 12: 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint17120197

APA StyleDong, J. M., & Zhong, H. (2025). Systematic Review: Proteomics-Driven Multi-Omics Integration for Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology and Precision Medicine. Neurology International, 17(12), 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint17120197