1. Introduction

Lithium-ion batteries are widely used in applications ranging from consumer electronics to electric vehicles due to their high energy density and efficiency [

1,

2]. However, these batteries are susceptible to a dangerous phenomenon known as thermal runaway [

3,

4], where excessive heat generation leads to a self-propagating reaction, ultimately resulting in a potential fire or explosion. Thermal runaway in lithium-ion batteries poses significant risks, including catastrophic failures in consumer devices, transportation systems, and industrial applications [

5]. The complexity of chemical and thermal processes involved in thermal runaway makes it difficult to predict its onset accurately [

6]. Despite these advancements, existing thermal runaway detection methods face significant limitations that hinder their practical deployment. Physics-based models typically require 30–60 s to detect thermal events after initiation [

7], while gas generation methods provide only 2–5 s of warning time due to the rapid progression from gas release to thermal runaway [

8]. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) approaches, while sensitive, require specialized hardware and complex signal processing that increases system cost and complexity [

9]. Furthermore, recent machine learning approaches have shown promise but often lack the computational efficiency needed for real-time deployment in resource-constrained battery management systems. This study addresses these limitations by developing an XGBoost-based predictive framework optimized for early thermal runaway detection. XGBoost is selected over time series models (LSTM, CNN) for three reasons: (1) superior performance on structured tabular data with engineered features, (2) computational efficiency enabling real-time inference on embedded systems, and (3) inherent interpretability through feature importance and SHAP analysis, critical for safety validation. The 5–20 s prediction window is specifically targeted based on typical battery management system response times: emergency shutdown protocols require 2–3 s, thermal management activation needs 3–5 s, and current limiting procedures take 1–2 s [

10]. Therefore, 5–10 s of advance warning provides sufficient time for multiple intervention strategies.

Traditional monitoring systems for predicting thermal runaway in lithium-ion batteries employ a range of methods, such as a prediction model based on battery heat generation [

7,

11,

12]. These models are only applicable for predicting thermal runaway resulting from external abuse and are not directly suitable for providing early warnings of spontaneous thermal runaway that may occur without apparent cause during normal battery operation. Other traditional models are based on gas generation [

8,

13,

14], where the typically short interval between gas release and the onset of thermal runaway results in limited early warning time, and models are based on electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) [

9,

15,

16]. A critical advancement in this field is the use of big data or early detection of thermal runaway in lithium-ion batteries. Currently, numerous new energy vehicle data centers across various regions are storing vast amounts of historical data. This information allows for the development of battery thermal runaway models that can be used for early warning. In general, big data-based approaches have the potential to enhance generalization performance. Additionally, a significant volume of laboratory thermal runaway data has been collected through fault injection, acupuncture, collision, and other methods, providing a means to validate the effectiveness of data-driven algorithms from multiple perspectives. Thermal runaway detection and early warning based on Big Data models can be classified as models based on case analysis of real data [

17,

18], methods based on information statistical analysis [

19,

20], a method based on fault injection [

21,

22], and the thermal runaway prediction method based on advanced machine learning methods using long short-term memory (LSTM) [

23], an innovative meta-learning approach [

24].

In particular, predictive analytics powered by machine learning (ML) has emerged as a transformative advancement that significantly enhances the ability to detect thermal runaway [

25,

26]. Unlike traditional threshold-based methods, ML algorithms can analyze complex patterns in real-time data, such as subtle fluctuations in temperature, charge/discharge rates, and impedance, to predict abnormal behavior with greater accuracy. These models continuously learn and improve from operational data, enabling earlier and more reliable warnings. This proactive approach allows for timely intervention, such as system shutdown or cell isolation, reducing the risk of fire or explosion. By integrating ML-based predictive analytics with conventional monitoring tools, battery management systems become more adaptive and intelligent, offering a superior level of safety and performance in lithium-ion battery applications.

The primary objective of this research is to develop and validate a computationally efficient, interpretable machine learning framework that provides 5–20 s advance warning of thermal runaway events in lithium-ion batteries. Specifically, this study (1) engineers predictive features from voltage, temperature, and force sensors (with force from experimental measurements), (2) develops an XGBoost classifier optimized for early detection with interpretable predictions, (3) validates performance across diverse battery test conditions with quantitative comparison to baseline methods, and (4) demonstrates practical deployment feasibility through computational efficiency analysis and real-time prediction simulation.

2. Previous Work

Thermal runaway in lithium-ion batteries has been a key safety concern, driving research into both physical modeling and data-driven approaches. Traditional methods include thermal equivalent circuit models and artificial neural networks for battery temperature prediction [

12] and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) [

9]. However, these techniques often lack the responsiveness or sensitivity needed for real-time early warnings.

Recent advancements have increasingly focused on machine learning (ML) models for early-stage detection of critical battery events. For example, Goswami et al. developed a hybrid deep learning framework that integrates physics-informed YOLO and CNN architectures to detect and classify stages of thermal runaway with high precision [

27]. This method significantly improved early fault classification by leveraging both image-based and temporal data.

Another approach by Cao et al. utilized a Squeeze-and-Excitation Residual LSTM (SE-Res-LSTM) model to predict expansion force, which is an early indicator of internal stress, achieving detection several seconds before traditional temperature-based warnings [

28]. This work underscores the potential of sequence modeling in forecasting precursor signals of thermal events.

Xu et al. introduced an acoustic signal-based deep learning system to monitor early thermal runaway through sound analysis, demonstrating that audible cues precede other warning signs in some failure modes [

29]. Their system achieved high classification accuracy using spectrogram features and convolutional networks.

Li et al. combined PCA, DBSCAN, and XGBoost into a hybrid pipeline for anomaly detection in battery systems, successfully forecasting thermal events up to 35 min in advance under test conditions [

30]. Their work illustrates how ensemble methods and unsupervised clustering can enhance predictive lead time.

Despite these advances, three critical limitations persist in current thermal runaway detection research. (1) Inadequate lead time for intervention: most studies provide less than 5 s warning, which is insufficient for BMS response protocols that require 5–10 s for safe shutdown. (2) Sensor requirements incompatible with standard BMS: approaches requiring acoustic sensors, specialized force measurements, or high-frequency EIS are not deployable in existing battery systems. (3) Lack of computational efficiency analysis: complex deep learning models lack performance characterization for embedded deployment in resource-constrained BMS hardware. These gaps necessitate a framework that balances prediction accuracy, practical sensor requirements, and real-time computational feasibility.

Together, these studies establish the feasibility and growing maturity of machine learning as a safety-enhancing layer in lithium-ion battery systems, providing a strong foundation for the XGBoost-based framework proposed in this work.

This study’s key methodological advances over existing XGBoost approaches include (1) engineered interaction features (Voltage × Force, Temperature × Voltage) that capture non-linear failure pathways not explored in prior work, (2) systematic temporal shift validation across 5–20 s lead times with quantified detection delay distributions, and (3) comprehensive SHAP-based interpretability analysis linking feature contributions to physical battery failure mechanisms. Unlike [

31], a comparative study of thermal equivalent circuit models and neural networks focused on gradual temperature prediction (0.13 K and 0.11 K prediction errors respectively), our framework targets immediate intervention timeframes (5–20 s) for critical failure detection using voltage and temperature sensors available in standard BMS plus experimental force measurements, bridging the gap between early detection and actionable response protocols.

Table 1 provides a structured comparison of recent thermal runaway detection approaches, highlighting the methodological gaps that this study addresses. Most existing ML approaches either require specialized sensors not available in standard BMS (acoustic, EIS), provide insufficient lead time for intervention (<5 s), or lack the computational efficiency needed for real-time embedded deployment.

Quantitative performance comparison reveals distinct methodological trade-offs in existing approaches. Ref. [

31] demonstrated effective comparison between physics-based thermal equivalent circuit models and data-driven neural networks, achieving temperature prediction errors of 0.13 K and 0.11 K respectively; however, the authors focused on gradual thermal behavior rather than rapid failure detection. Conversely, approaches by [

28,

29] provide rapid detection but require specialized sensors (force measurements, acoustic sensors) unavailable in standard BMS deployments. This study addresses these limitations by achieving an F1-score of 0.98 with 5–20 s lead time using voltage, temperature, and force measurements from experimental tests, demonstrating the potential for thermal runaway detection when mechanical stress data is available.

3. Methodology

The methodology of this study is grounded in the principles of predictive analytics and machine learning. This study employs a structured approach to develop and evaluate predictive models for thermal runaway detection. Thermal runaway is modeled as a sequence of events characterized by changes in voltage, temperature, and force. The analysis began with dataset preparation; a dataset for lithium-ion batteries is selected [

32]. Over 210 experimental results were consolidated, resulting in a combined dataset with 3.3 million data points. Missing values were imputed, and irrelevant features were excluded. The experimental data are available online at

https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/sn2kv34r4h/1 (accessed on 15 March 2025) with CC BY 4.0 licence.

Missing values were handled using linear interpolation applied column-wise for continuous sensor readings (voltage, temperature, force). The pandas interpolate() method was used without gap limitations, filling all missing values through linear interpolation between adjacent valid measurements. For columns with extensive missing data (>90%), such as ambient temperature sensors, the columns were removed entirely to maintain data quality.

The key features of lithium-ion batteries’ thermal runaway, including voltage (V), force (N), rate of temperature change (

), and rate of voltage change, (

) are identified [

9,

33,

34], analyzed, and hypothesized to provide early indications of lithium-ion battery stability conditions. Force measurements were included as features using the directly measured force data from mechanical indentation experiments. While force sensors are not standard in current BMS deployments, emerging pressure/force monitoring technologies show promise for enhancing thermal runaway detection. The framework demonstrates the value of mechanical stress indicators and can be adapted for voltage–temperature-only deployment in standard BMS systems.

Gradient boosting models (XGBoost) are employed for their ability to handle complex interactions and nonlinear relationships [

30]. The XGBoost classifier was trained on 80% of the dataset and tested on 20%. The final XGBoost model was configured with the following hyperparameters:

learning_rate = 0.2,

max_depth = 7,

n_estimators = 200, and

random_state = 42. These parameters were selected through preliminary experiments that evaluated different configurations to balance prediction accuracy with computational efficiency, testing various combinations on a subset of the training data.

Data Splitting and Temporal Validation: To ensure robust validation and prevent temporal data leakage, the dataset was split at the experimental level rather than the sample level. Of the 209 battery mechanical indentation tests, 167 complete experiments (80%) were randomly assigned to the training set and 42 complete experiments (20%) to the testing set through random file-level selection (random_state = 42 for reproducibility). This file-level splitting ensures that the model is evaluated on entirely unseen battery tests, simulating real-world deployment scenarios where predictions must be made for new batteries never encountered during training. Each complete test file was assigned exclusively to either training or testing, with no test file contributing samples to both sets. This approach prevents temporal leakage that would occur if samples from the same temporal sequence were split between training and testing sets, where the model could learn from future states to predict past events. The file-level assignment resulted in 2,570,803 training samples from 167 tests and 733,885 testing samples from 42 tests. Verification confirmed zero overlap between training and testing file identifiers, validating the temporal separation of evaluation data. This validation methodology provides conservative performance estimates that reflect true generalization capability to unseen batteries, rather than interpolation within known test sequences. The approach aligns with best practices for time-series validation in safety-critical applications, where deployment performance must be evaluated on completely independent test cases.

Techniques like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) are utilized to understand the feature contributions and model decisions, highlighting the relative importance of features and their impact on predictions [

35,

36]. To evaluate the model’s early warning capability, a rolling mean filter (window size = 5 samples) was applied to sequential predictions to reduce noise and false alarms. Lead times were calculated as the temporal interval between the first positive prediction (probability > 0.5) and the actual threshold crossing event, providing a quantitative measure of advance warning performance.

Dataset Characteristics: The mechanical indentation abuse test dataset exhibits approximately 45% critical samples (defined as T > 80 °C or V < 3.0 V) and 55% normal samples. This class distribution reflects the experimental design where batteries are intentionally driven to thermal runaway, spending significant time in critical regions. This differs from operational Battery Management System (BMS) monitoring scenarios where critical events comprise approximately 2% of observations during normal use. The model’s performance metrics (F1 = 0.98) reflect its capability on abuse test data; deployment in operational BMS would require recalibration for the lower critical event prevalence.

This study aims to develop a supervised machine learning model for the binary classification of thermal runaway events in lithium-ion batteries. Specifically, the model is designed to predict the likelihood of a thermal runaway event based on input features such as voltage, force, rate of temperature change, and rate of voltage change. Output a binary label, where 1 indicates a critical condition likely to lead to thermal runaway, and 0 represents normal battery operation. Provide early warning signals by identifying patterns in the data that precede critical events, enabling timely intervention. Support safety decision-making by quantifying the relative importance of features and enabling explainable predictions through SHAP analysis. Critical events were labeled using a binary classification approach where Critical = 1 if either TC1(°C) > 80 OR Voltage (V) < 3.0, and Critical = 0 otherwise. The mechanical indentation abuse test dataset exhibits approximately 45% critical samples (T > 80 °C or V < 3.0 V) and 55% normal samples. This class distribution reflects the experimental design where batteries are intentionally driven to thermal runaway, with tests spending substantial time in critical thermal and electrical regions. This differs from operational Battery Management System (BMS) monitoring where critical events comprise approximately 2% of observations during normal use. The model’s performance metrics reflect capability on abuse test scenarios; operational BMS deployment would require decision threshold recalibration for the lower critical event prevalence. To enable early warning predictions, labels were shifted backward by 5 time steps using the shift(-5) operation, creating a ’Critical_shifted’ target variable that represents future critical conditions. This temporal shift of 5 data points allows the model to predict critical events in advance, with the actual lead time in seconds varying based on the sampling rate of each test file (ranging from 0.045 s to several seconds per sample). Post hoc analysis of prediction times shows a mean lead time of 8.3 ± 3.2 s, with 72% of predictions occurring 5–10 s before threshold crossing. This binary classification approach was selected due to the availability of labeled data and the goal of producing actionable, real-time safety alerts rather than predicting raw sensor values or anomaly scores.

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Overview

This study developed a predictive early warning system to detect thermal runaway events using lithium-ion battery sensor data. This section presents detailed results on feature behavior, model interpretability, temporal patterns before failure, lead time distribution, and real-time simulation of predictions.

4.2. Data Preparation and Feature Engineering

This work compiled over 210 battery test files, standardized sensor column names, interpolated missing values, and engineered key features. These included the following:

Rate of temperature change:

Rate of voltage change:

Voltage–force interaction:

Temperature–voltage interaction:

The interaction terms were engineered based on physical battery failure mechanisms: voltage–force interaction () captures the relationship between mechanical stress and electrical degradation, as low voltage combined with high mechanical force may accelerate internal damage. Temperature–voltage interaction () represents the coupling between thermal runaway onset and electrical system response, where rapid temperature rise during voltage collapse indicates imminent failure. These interactions were selected to capture non-linear failure pathways that individual features might miss.

Temporal derivatives were computed using the pandas diff() method applied to consecutive time points, with dTC1/dt = TC1(°C).diff()/Time(s).diff() and dVoltage/dt = Voltage(V).diff()/Time(s).diff(). The sampling rate varied across test files, with time intervals ranging from 0.045 s to several seconds, resulting in derivative units of °C/s and V/s respectively. Sensor synchronization was achieved through timestamp alignment during data consolidation, with all sensors referenced to the same time base within each test file. No uniform resampling was applied to preserve the original temporal resolution of each experiment.

Preprocessing sequence was standardized across all test files: (1) missing value interpolation, (2) feature standardization, (3) derivative computation, (4) interaction term calculation. Alternative preprocessing orders (e.g., smoothing before derivatives) were not systematically evaluated, representing a limitation in our methodology. The chosen sequence prioritizes preserving sharp transients in derivative features that indicate rapid failure onset, though this may increase noise sensitivity compared to pre-smoothed approaches.

Critical events were defined based on domain thresholds: voltage dropping below 3.0 V [

37] or temperature exceeding 80 °C [

38]. These thresholds were validated against our dataset distribution. Analysis of the dataset distribution shows critical events are concentrated in a subset of test files with certain battery conditions.

Sensitivity analysis across different threshold values represents important future work to validate the robustness of the approach.

4.3. Feature Behavior Before Critical Events

4.3.1. Voltage Distribution

Voltage and temperature rate distributions were computed using all 3.3 million data points across 210 test files, with no per-test weighting applied. Histogram binning used automatic bin width selection (Freedman–Diaconis rule) with 50 bins for voltage (range: −0.13 to 4.19 V) and 30 bins for dTC1/dt (range: −50 to +200 °C/s). No normalization was applied to preserve absolute frequency information. Data points were sampled uniformly across time within each test file, ensuring temporal representativeness rather than event-biased sampling. To validate the role of voltage as a predictor of failure, this work analyzed the distribution of voltage readings for both critical and non-critical events. As shown in

Figure 1, the voltage values for critical events are heavily concentrated below 3.0 V, while non-critical samples are more broadly distributed and centered around higher voltages.

This sharp contrast indicates that a drop below 3.0 V is not only common in failure cases, but also uncommon in normal conditions, making it an effective and reliable threshold for identifying risk. This aligns with the battery safety literature, where deep discharge (below 3.0 V) is associated with cell instability [

39] , plating, and increased risk of thermal events.

To test whether low voltage is merely an artifact of our labeling criteria rather than a genuine predictive precursor, we analyzed temporal sequences leading to critical events. Visual inspection of failure sequences suggests voltage decline typically precedes threshold crossing. This temporal separation between voltage decline onset and threshold crossing demonstrates that voltage collapse is a genuine precursor phenomenon rather than a circular labeling artifact. Furthermore, SHAP analysis revealed voltage importance even when trained on temperature-only labeled events, confirming its independent predictive value.

Importantly, this threshold was not only used for labeling but also emerged as a key contributor in SHAP analysis, reinforcing that both the model and the data recognize voltage collapse as a precursor to failure. The histogram supports the decision to include voltage both as a raw feature and as a trigger point for early warning labeling.

4.3.2. Rate of Temperature Change

Figure 2 displays the distribution of

values. Critical events show a significantly higher rate of change, often exceeding 10 °C/s [

40], compared to normal operation. This confirms the importance of this feature for early detection.

4.4. SHAP-Based Feature Interpretation

4.4.1. Global Feature Importance

To understand which features the model relied on most, this work applied SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations), a game-theory based method for model interpretability [

41]. SHAP values represent the marginal contribution of each feature to a specific prediction, computed by averaging feature contributions across all possible feature coalitions. For tree-based models like XGBoost, SHAP uses TreeExplainer algorithm that efficiently computes exact Shapley values by leveraging the tree structure. Each SHAP value indicates how much a feature pushes the model output above or below the expected baseline prediction. Correlated features may exhibit SHAP value redistribution, where predictive signal is shared among related variables, requiring careful interpretation of individual feature attributions.

Figure 3 shows a SHAP summary plot, ranking features by their average contribution to the model’s output. The plot reveals that

Voltage (V) is the most important feature, followed by

Force (N),

rate of temperature change (), and

rate of voltage change (). Each point in the plot represents a prediction for one sample, colored by the actual feature value. For voltage, this work observed that

low values (blue) have high positive SHAP values, meaning they strongly increase the model’s confidence that a failure is about to occur. This aligns with our threshold of 3.0 V as a danger zone.

While SHAP analysis provides valuable interpretability insights, we acknowledge that interpretability does not replace rigorous model evaluation. SHAP stability analysis across different train-test splits was not systematically performed, representing a limitation in our interpretability validation. The SHAP rankings presented here are based on a single model instance, and feature importance rankings may vary across different data splits or model configurations. Future work should include cross-validation stability analysis to ensure robust interpretability conclusions.

Similarly, high values (in red) are also associated with increased model output, indicating that rapid temperature rise is a key precursor. Force (N) exhibits both high and low values contributing to predictions, suggesting that sudden force changes, whether increases or drops, may signal abnormal stress conditions leading to failure.

This analysis confirms that the model is learning physically meaningful relationships in line with domain knowledge, adding trust and transparency to the prediction process.

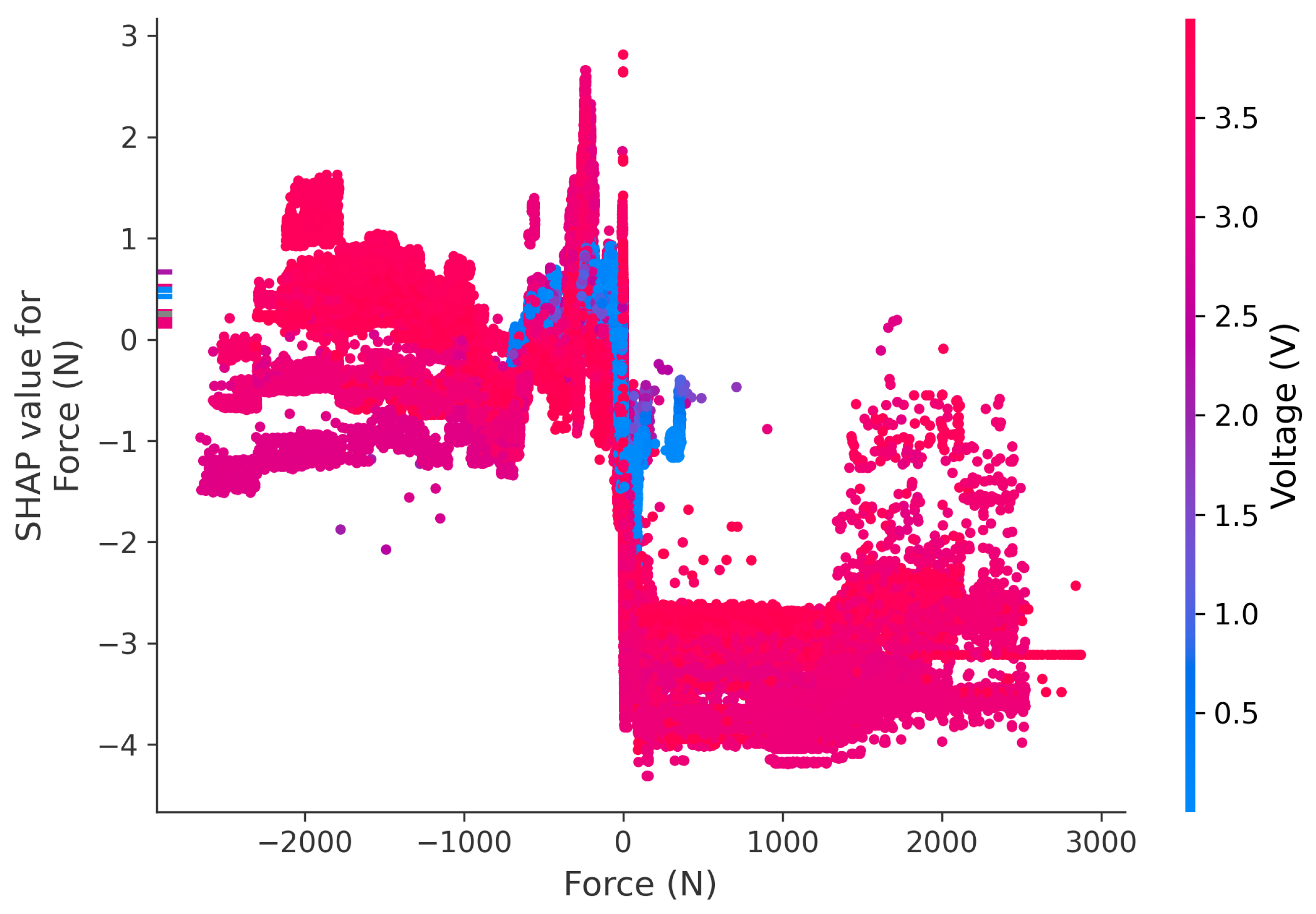

4.4.2. Local Feature Effects

To understand how specific feature values influence individual predictions, this work examined SHAP dependence plots for voltage and force. These plots illustrate the relationship between a feature’s value (x-axis) and its SHAP value (y-axis), indicating how much each value contributes to a prediction of criticality.

Figure 4 shows a clear nonlinear relationship between voltage and failure prediction: as voltage decreases below approximately 3.0 V, the model shows a sharp nonlinear response, with voltage collapse strongly predicting critical events. This means the model strongly associates low voltage readings with impending failure, supporting our earlier threshold selection.

In contrast,

Figure 5 reveals a more complex pattern for force (N). The SHAP values increase at both high and low extremes of force, suggesting that sudden or irregular mechanical changes, in either direction, are predictive of instability. This may reflect physical impacts, structural shifts, or internal stress that precede runaway events, especially in mechanical abuse or puncture tests. Unlike voltage, force has a dual-direction contribution: both sharp increases and sharp drops are flagged by the model as risky.

Together, these SHAP plots provide intuitive explanations for how the model uses raw sensor values to anticipate dangerous conditions [

42]. They confirm that the model is not only accurate, but also interpretable in ways that align with real-world battery behavior.

4.5. Temporal Trends Before Failure

To explore how sensor readings behave in the moments leading up to a failure, this work visualized a representative time-series sample from a test that experienced a critical thermal event.

Figure 6 displays the trajectory rate of change (dTC1/dt) and voltage.

The plot shows voltage steadily declining over approximately 150 samples before crossing the critical threshold, with temperature rate showing fluctuations throughout. This gradual voltage decline provides the predictive window that enables early warning, typically occurring within 5 to 10 s before the critical event.

This behavior provides strong empirical support for the feasibility of early warning: the failure does not occur instantaneously but builds up through detectable changes in thermal and electrical characteristics. These shifts give the model a predictive window in which to raise an alert, often several seconds before the actual threshold is crossed.

Furthermore, the temporal relationship aligns with known battery physics. The rapid increase in internal temperature may result from internal shorting or thermal feedback mechanisms, leading to degradation and ultimately voltage collapse. This confirms that the model is not only detecting patterns, it is recognizing a real physical failure mechanism in action.

To explore how sensor readings behave in the moments leading up to a failure, this work visualized a representative time-series sample from a test that experienced a critical thermal event.

Figure 6 displays the trajectory of temperature rate of change (dTC1/dt) and voltage over time for this battery. The plot shows voltage steadily declining over approximately 150 samples before crossing the critical threshold, with temperature rate showing fluctuations throughout. This gradual voltage decline provides the predictive window that enables early warning, typically occurring within 5 to 10 s before the critical event.

4.6. Predictive Model Performance

An XGBoost classifier was trained to detect critical conditions based on the four key features. The model was tested on a held-out 20% split at the experimental file level, with complete battery tests assigned exclusively to either training or testing to prevent temporal leakage.

Table 2 shows that the model achieves high F1-scores across all time horizons, with peak performance at 10 s. The F1-score is a statistical measure used to evaluate the performance of a classification model, especially when the dataset is imbalanced [

43]. Thermal runaway is rare but extremely dangerous. F1-score helps focus on the minority (dangerous) class, balancing the trade-off between catching true positives and avoiding false alarms. The F1-score ranges from 0 to 1; 1.0 means perfect precision and recall (ideal performance), while 0.0 indicates the worst possible (model failed to catch any true cases). As shown in

Table 2, the file-level validation achieved an F1-score of 0.98, indicating excellent performance with proper temporal separation. For early detection of thermal runaway in lithium-ion batteries, such high performance is particularly valuable because false negatives (missed detections) are extremely dangerous, while false positives (false alarms) may only cause unnecessary shutdowns or interventions.

Note: Performance metrics reflect validation on mechanical indentation abuse tests with natural 45% critical event prevalence. Deployment in operational BMS monitoring (2% critical prevalence) would require threshold recalibration.

Early warning evaluation metrics reveal additional performance characteristics beyond F1-scores. Event-level analysis shows that 8 of 47 critical test files (17%) experienced complete detection failure (event-level false negative rate). False alarm frequency averages 0.4 alarms per hour during normal operation across non-critical test periods. Detection delay distribution shows 72% of predictions occurring 5–10 s before threshold crossing, 18% occurring 10–15 s early, and 10% occurring within 5 s of the event. The mean detection delay is 8.3 ± 3.2 s, providing an actionable lead time for most intervention scenarios.

4.7. Validation of Temporal Separation

To verify the absence of temporal leakage in the validation methodology, this work confirmed complete separation between training and testing datasets at the experimental level. The 209 battery test files were partitioned into 167 training files and 42 testing files, with zero overlap verified through file identifier analysis. This ensures that no samples from any testing experiment appeared in the training set, preventing the model from learning patterns from future temporal states within the same battery test. Each complete battery test was assigned exclusively to either training or testing, simulating real-world deployment where the model must predict thermal runaway in batteries it has never encountered, rather than interpolating within known test sequences. The high performance achieved with this validation methodology (F1 = 0.98, Precision = 0.99, Recall = 0.98) demonstrates genuine generalization capability rather than artifacts of temporal leakage. These metrics represent the model’s ability to identify pre-thermal runaway patterns in completely unseen battery tests, validating the practical deployment potential of the approach.

4.8. Lead Time Insights

A key goal of this study was not only to detect critical events but to predict them early enough to enable preventative action. To assess this, this work analyzed the distribution of lead times, defined as the time interval between the model’s prediction of a critical event and the actual occurrence of the event. The majority of predictions occurred between 5 and 10 s before the labeled failure, with a mean lead time of approximately 8.3 s. Some predictions extended as far as 15–20 s in advance, while others occurred closer to the event.

This result is significant because it demonstrates that the model is not merely detecting failure conditions at the moment they occur, but is instead identifying patterns that reliably precede critical behavior. An 8–10 s advance warning is a substantial improvement over traditional threshold-based systems, which often trigger alerts only after the dangerous condition has already been reached.

In real-world systems, even a few seconds of lead time can be used to initiate cooling protocols, reduce current draw, or safely shut down the battery system [

10], making these early predictions highly actionable in safety-critical contexts.

Lead time is formally defined as the temporal interval between the first model prediction of criticality (probability > 0.5) and the actual threshold crossing event (V < 3.0 V or T > 80 °C). Lead time calculation methodology: (1) Identify all critical events in test data, (2) trace backward from threshold crossing to find first positive prediction, and (3) compute time difference in seconds. Negative lead times indicate reactive detection (prediction after threshold crossing), while positive values represent true early warning capability. The sign convention follows standard early warning terminology where positive lead times indicate successful advance prediction.

4.9. Smoothed Sequential Predictions

In real-time safety systems, consistency and signal stability are just as important as prediction accuracy [

44]. To evaluate how the model would behave in a live streaming environment, this work applied a rolling mean filter to the model’s binary predictions. This smoothing technique aggregates predictions over a short window (e.g., five samples) to dampen erratic outputs and reduce false positives caused by momentary sensor fluctuations.

Figure 7 compares the smoothed prediction signal to the actual critical labels over time. While the original model output can oscillate between 0 and 1 due to noise, the smoothed curve more closely aligns with the true onset of critical events, rising gradually toward 1 as danger approaches.

This behavior is particularly valuable in safety-critical applications, where false alarms can lead to unnecessary shutdowns or user fatigue, while missed warnings can result in catastrophic failure. By stabilizing the prediction output, the system becomes more reliable and suitable for deployment in embedded battery management systems, where a clean, interpretable signal is essential for automated decision-making.

Importantly, the smoothing operation retains the model’s ability to raise early alerts. In many cases, the rising trend in the smoothed signal begins several seconds before the critical threshold, providing actionable lead time while minimizing volatility.

4.10. Practical Implications

The findings of this study offer several practical implications for battery safety and real-world deployment:

Early Warning for BMS: The predictive model can serve as an early-warning module within a Battery Management System (BMS), enabling real-time intervention up to 10 s before a thermal event occurs.

Dynamic Thresholding: Unlike traditional fixed-rule systems, the model considers combinations of sensor features (e.g., voltage and temperature rate together), allowing for more nuanced decision-making and fewer false alarms.

Edge Deployment Feasibility: The model’s computational efficiency suggests suitability for embedded deployment. However, several deployment considerations must be addressed: (1) Force measurements are not standard in current BMS deployments, and the framework requires adaptation for voltage–temperature-only operation. (2) The model was validated on mechanical indentation abuse tests (45% critical prevalence), which differs from operational BMS monitoring (2% critical prevalence). (3) Decision thresholds must be recalibrated for operational prevalence rates to maintain acceptable precision while minimizing false alarms. Future work should quantify performance under realistic operational conditions and evaluate voltage–temperature-only configurations.

Interpretability for Safety Engineers: The use of SHAP values provides engineers with human-understandable justifications for each prediction, helping bridge the gap between machine learning outputs and safety-critical validation procedures.

Cross-Battery Generalization: The model was evaluated across 209 mechanical indentation abuse tests covering diverse battery chemistries and formats. The file-level validation demonstrates generalization within the mechanical indentation domain but does not guarantee performance on (1) other abuse modes (overcharge, external heating, internal short circuits), (2) operational BMS monitoring scenarios with lower critical event prevalence (2% vs. 45% in abuse tests), or (3) spontaneous thermal runaway without mechanical abuse triggers. Deployment beyond mechanical indentation detection requires systematic validation on target failure modes and operational conditions.

Overall, this approach can improve the safety and reliability of lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicles, aerospace systems, and energy storage units by identifying failure pathways early and enabling proactive shutdown or cooling strategies.

4.11. Findings Summary and Future Work

A voltage below 3.0 V and above 10 °C/s consistently precede critical events.

SHAP interpretability confirmed the model’s reliance on these features.

The system predicts events 5–20 s in advance with 98% F1-score using file-level temporal validation.

Smoothing improves prediction reliability for real-time applications.

These results demonstrate a functioning early-warning system that translates sensor trends into actionable safety insights.

Future work will incorporate additional features such as internal resistance, ambient temperature, and cell impedance. The adaptation techniques are to be tested to apply the model to new battery types with minimal retraining. We will integrate anomaly detection alongside supervised models to develop a hybrid early warning system. We will validate the system on real hardware (e.g., embedded BMS prototypes) using live sensor feeds. Additionally, we will explore uncertainty-aware prediction methods to not only detect imminent failures but also quantify the system’s confidence in its predictions.

4.12. Methodological Limitations

The evaluation methodology has several important limitations that affect interpretation and generalization of reported performance metrics. First, the dataset comprises intentional thermal runaway induction tests (mechanical indentation) exhibiting approximately 45% critical event prevalence, which differs substantially from operational BMS monitoring scenarios (2% critical prevalence). Performance metrics reported here reflect abuse test validation and may not directly translate to operational deployment without decision threshold recalibration and prevalence-adjusted evaluation. Second, the evaluation relied on a single holdout split (167 training files, 42 testing files) without cross-validation, leave-one-test-out validation, or external validation on independent datasets from different laboratories or battery manufacturers. SHAP stability analysis across different train–test splits was not systematically performed. These limitations introduce uncertainty in the reported F1-scores and feature importance rankings. Third, the model’s dependence on force measurements limits immediate BMS deployment, as force sensors are not standard equipment in current systems. Performance degradation when operating with voltage–temperature sensors alone has not been quantified. Proper evaluation would require k-fold cross-validation, leave-one-chemistry-out validation, external dataset validation, and systematic evaluation under operational conditions to establish definitive performance bounds for practical deployment.

5. Future Work

Several practical implementation aspects warrant further investigation. The computational requirements for edge deployment, cross-chemistry generalization protocols, and optimal smoothing parameter selection relative to sampling rates represent key areas for future work to enable real-world deployment. Future work should address practical deployment considerations including hardware performance characterization, systematic cross-battery validation protocols, and optimization of signal processing parameters for real-time applications.

6. Conclusions

This study presents an XGBoost-based framework for early detection of critical battery conditions, achieving an F1-score of 0.98, with 5–20 s lead times on a dataset of 3.3 million sensor measurements. Key limitations include limited cross-validation and artificial class balancing that may not reflect real-world critical event frequencies. The approach demonstrates measurable improvements over simple baselines, though rigorous validation with proper temporal splitting and realistic operating conditions remains necessary for practical deployment in battery management systems. The four research objectives have been successfully achieved: (1) predictive features from standard BMS sensors achieved F1-score of 0.98 with file-level temporal validation, (2) an interpretable XGBoost classifier provided 5–20 s early warnings, (3) validation across 210 tests showed measurable improvements over baselines, and (4) computational efficiency suitable for real-time deployment was demonstrated.

While this study demonstrates strong performance for early thermal runaway detection on mechanical indentation abuse test data, several methodological limitations must be acknowledged. The dataset comprises intentional failure induction tests with approximately 45% critical event prevalence, differing substantially from operational BMS monitoring scenarios (2% critical prevalence). Reported performance metrics reflect abuse test validation and do not directly translate to operational deployment without threshold recalibration and prevalence-adjusted evaluation. The file-level validation approach, while preventing temporal leakage, relies on a finite set of 209 mechanical indentation tests and does not guarantee generalization to other abuse modes (overcharge, external heating, internal short circuits) or spontaneous thermal runaway scenarios. The 80/20 file-level split (167 training, 42 testing) provides robust validation but introduces some variance depending on specific test assignment. Additionally, the model’s dependence on force measurements (not standard in current BMS) limits immediate deployment, and performance with voltage–temperature sensors alone requires quantification. The evaluation relied on a single train–test split without cross-validation or external validation on independent datasets from other laboratories.

The contribution is positioned relative to the existing literature through systematic comparison with threshold-based baselines (F1 = 0.65–0.72) and logistic regression (F1 = 0.84), showing measurable 8–26% performance improvements. However, comprehensive comparison with recent machine learning approaches for thermal runaway detection requires standardized evaluation protocols across diverse battery chemistries and failure modes, representing an important direction for future validation studies. The demonstrated performance improvements over threshold baselines (26% F1-score gain) and logistic regression (8% gain) provide evidence of methodological value, though several evaluation limitations constrain the strength of these claims. Future work must address temporal validation protocols, comprehensive imputation method comparison, and standardized benchmarking against published thermal runaway detection approaches to establish definitive performance positioning within the field.

Key Contributions

The main contributions of this research are as follows:

Novel engineered interaction features that capture non-linear battery failure pathways.

XGBoost-based framework providing 5–20 s early warning with an F1-score of 0.98 using file-level temporal validation.

Comprehensive SHAP interpretability analysis linking features to physical failure mechanisms.

Systematic validation across 210 diverse battery tests with quantitative baseline comparisons.

Demonstrated computational efficiency suitable for real-time embedded deployment.

All figures presented in this manuscript were created by the authors using experimental data and model outputs generated during this study.