Physics-Informed Temperature Prediction of Lithium-Ion Batteries Using Decomposition-Enhanced LSTM and BiLSTM Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

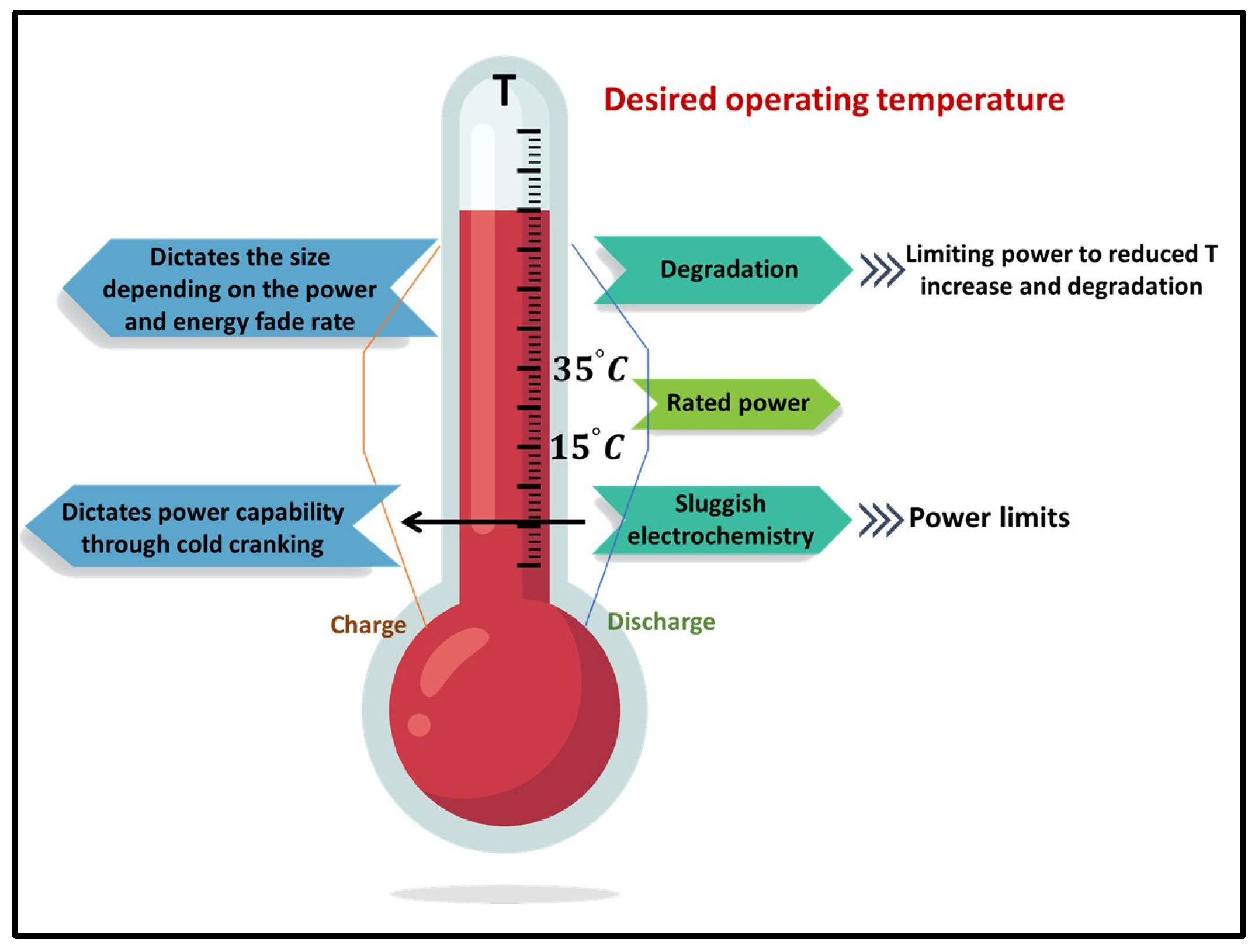

1.1. Thermal Significance of Lithium-Ion Batteries

1.2. Limitations of Conventional Temperature Monitoring

1.3. Challenges of Existing Modeling Approaches

1.4. Temperature as a Multi-Component Physical Signal

1.5. Contributions of This Research

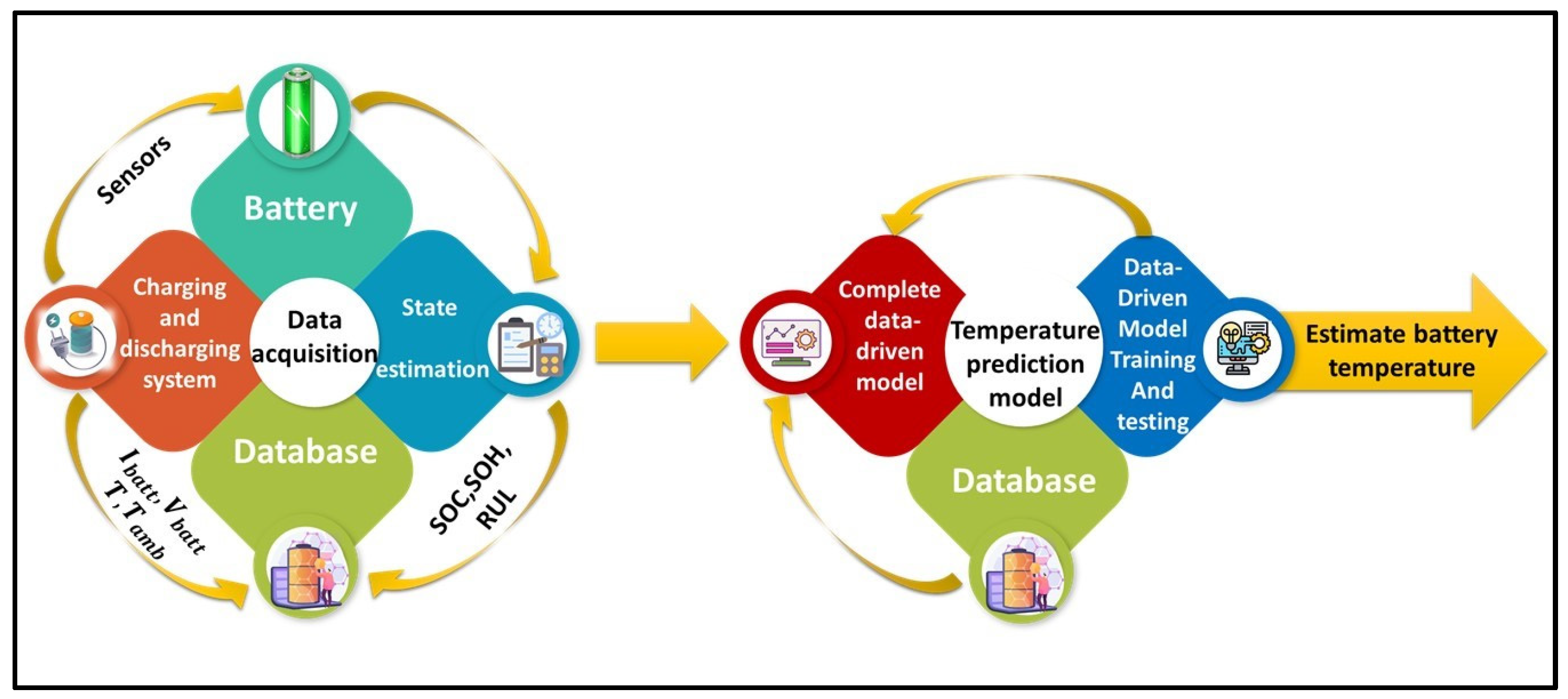

2. Methodology

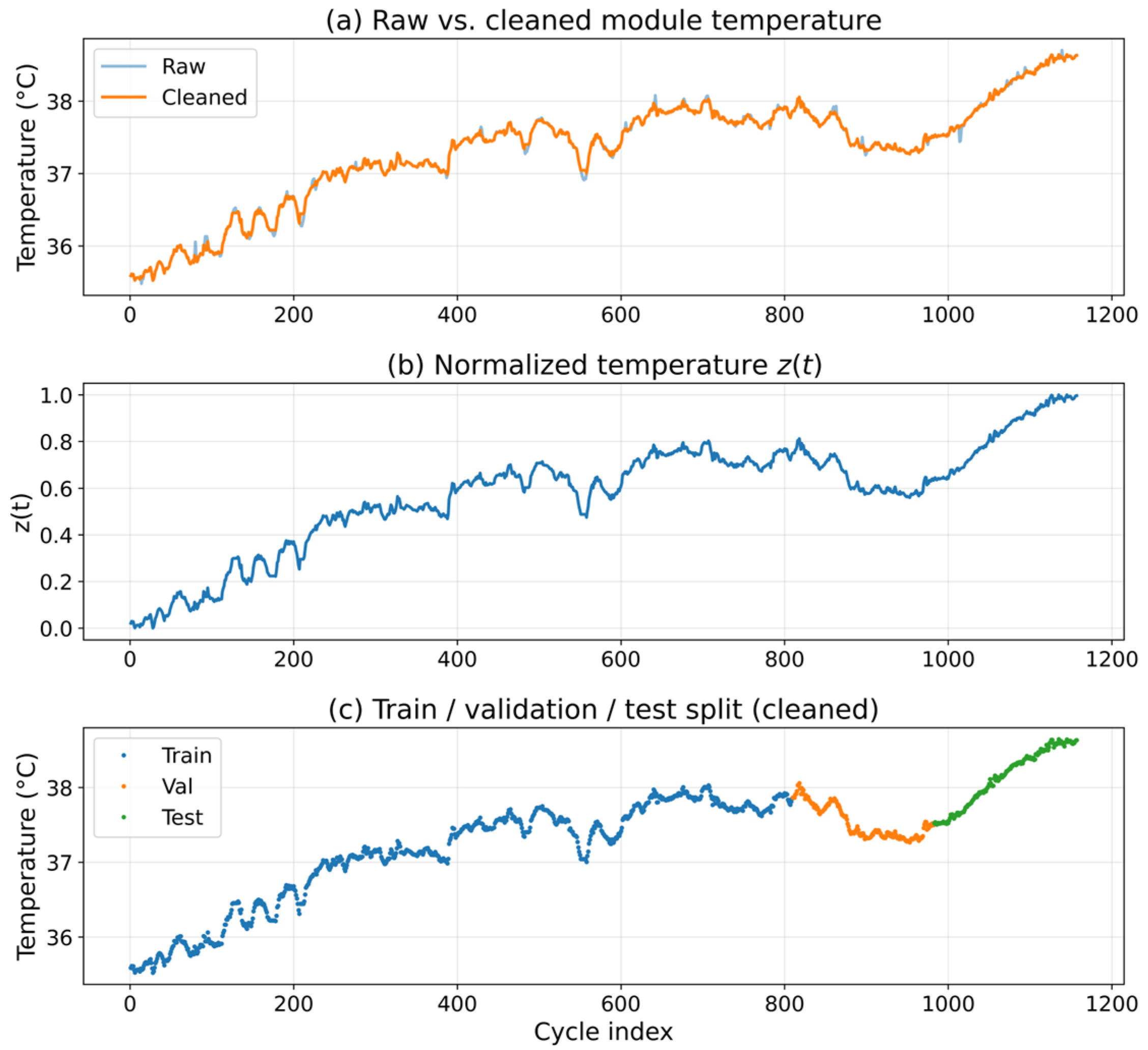

2.1. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

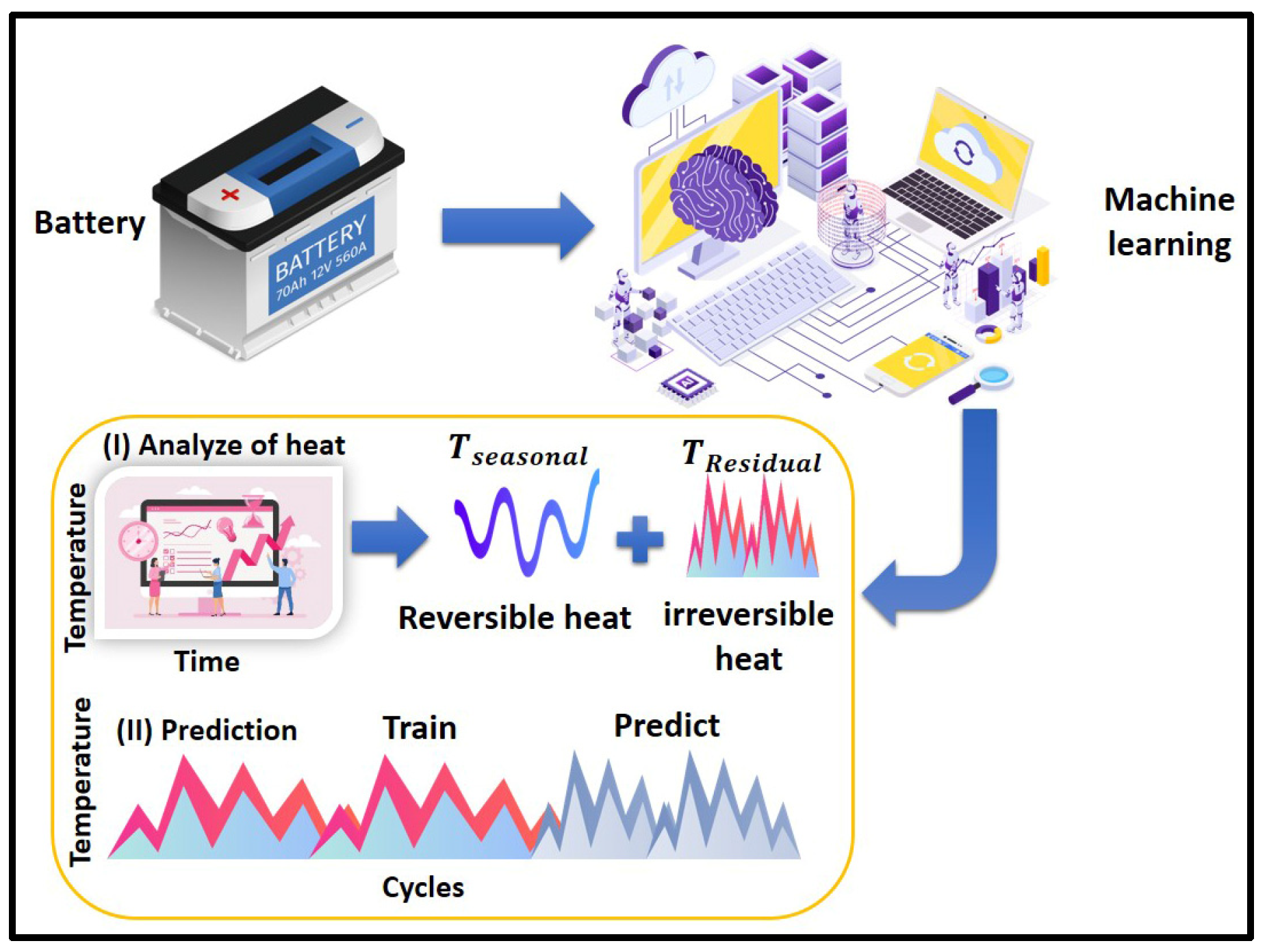

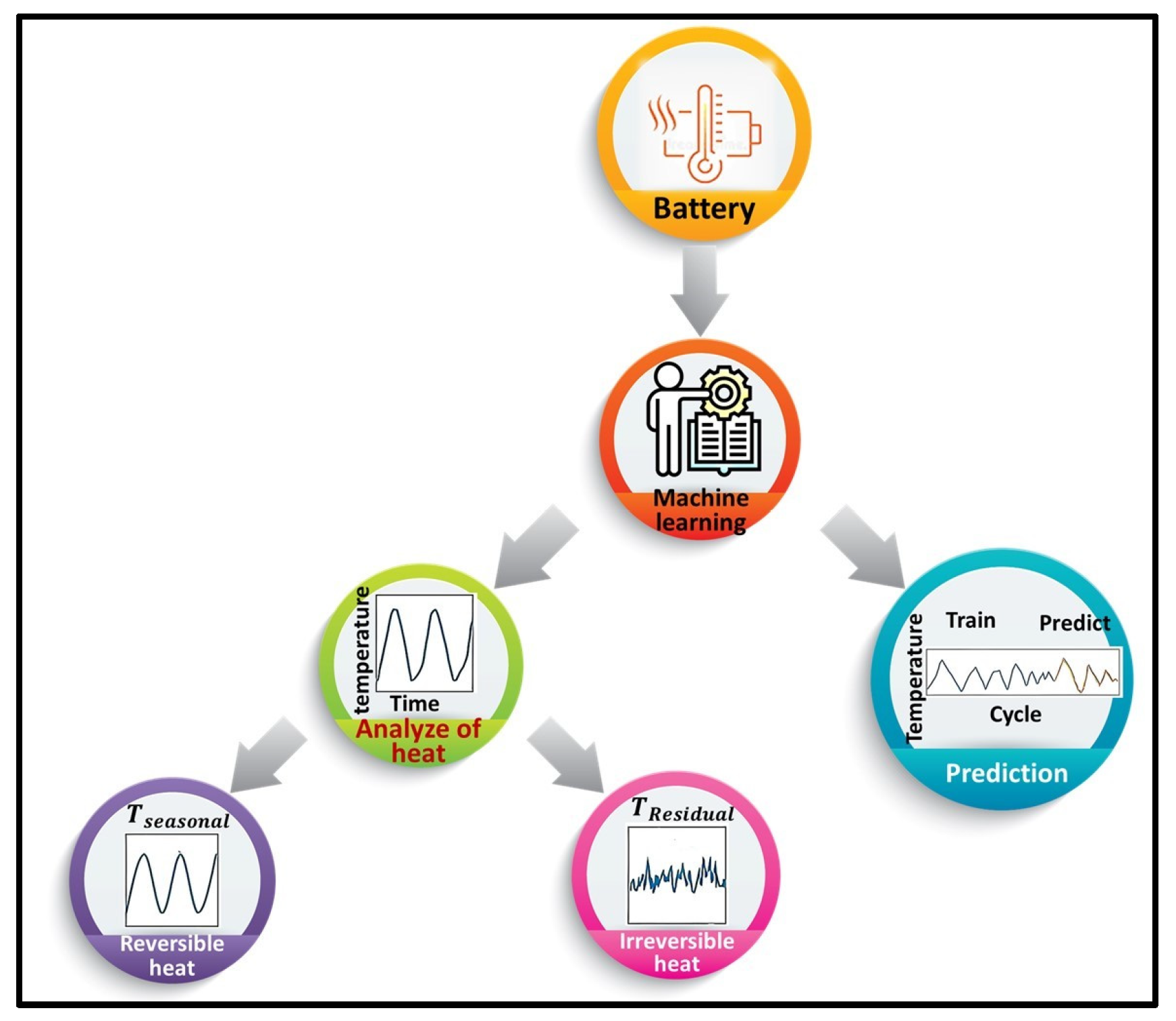

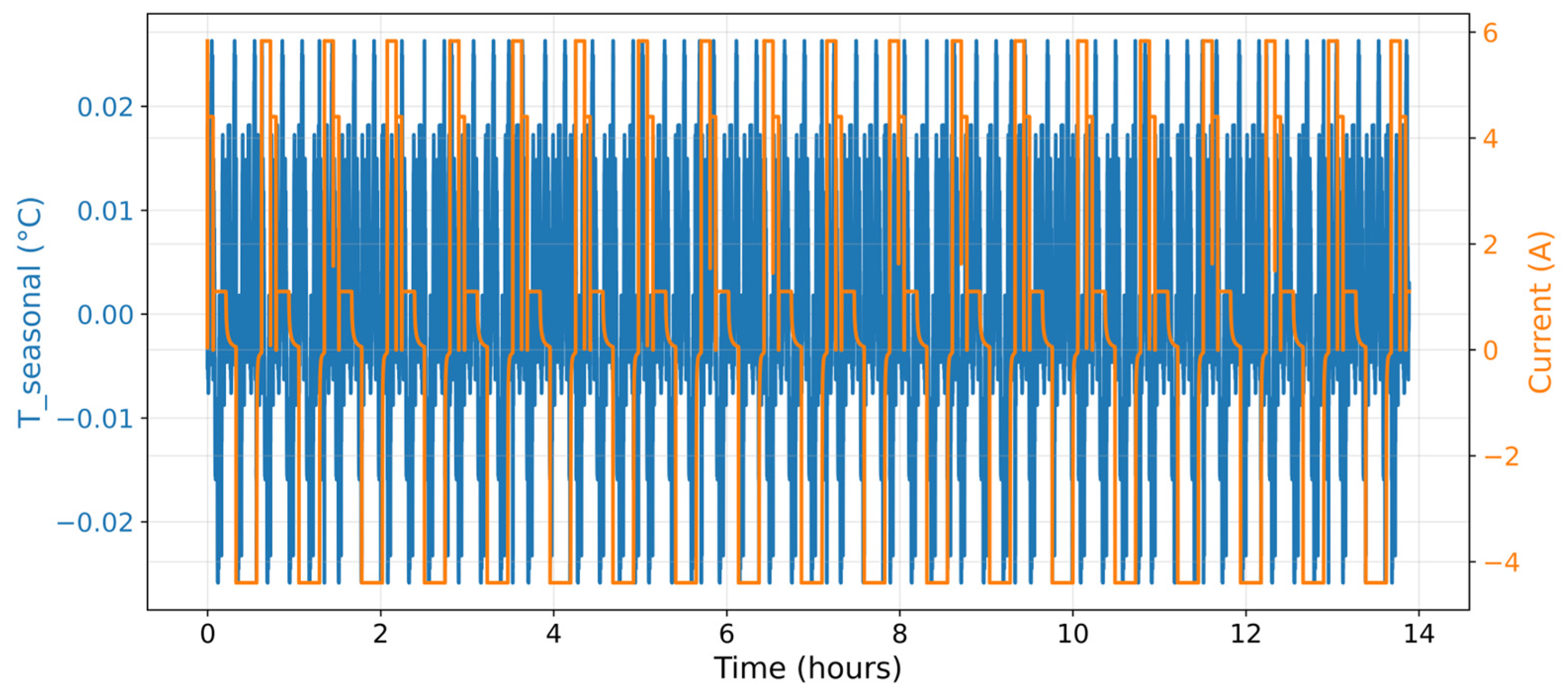

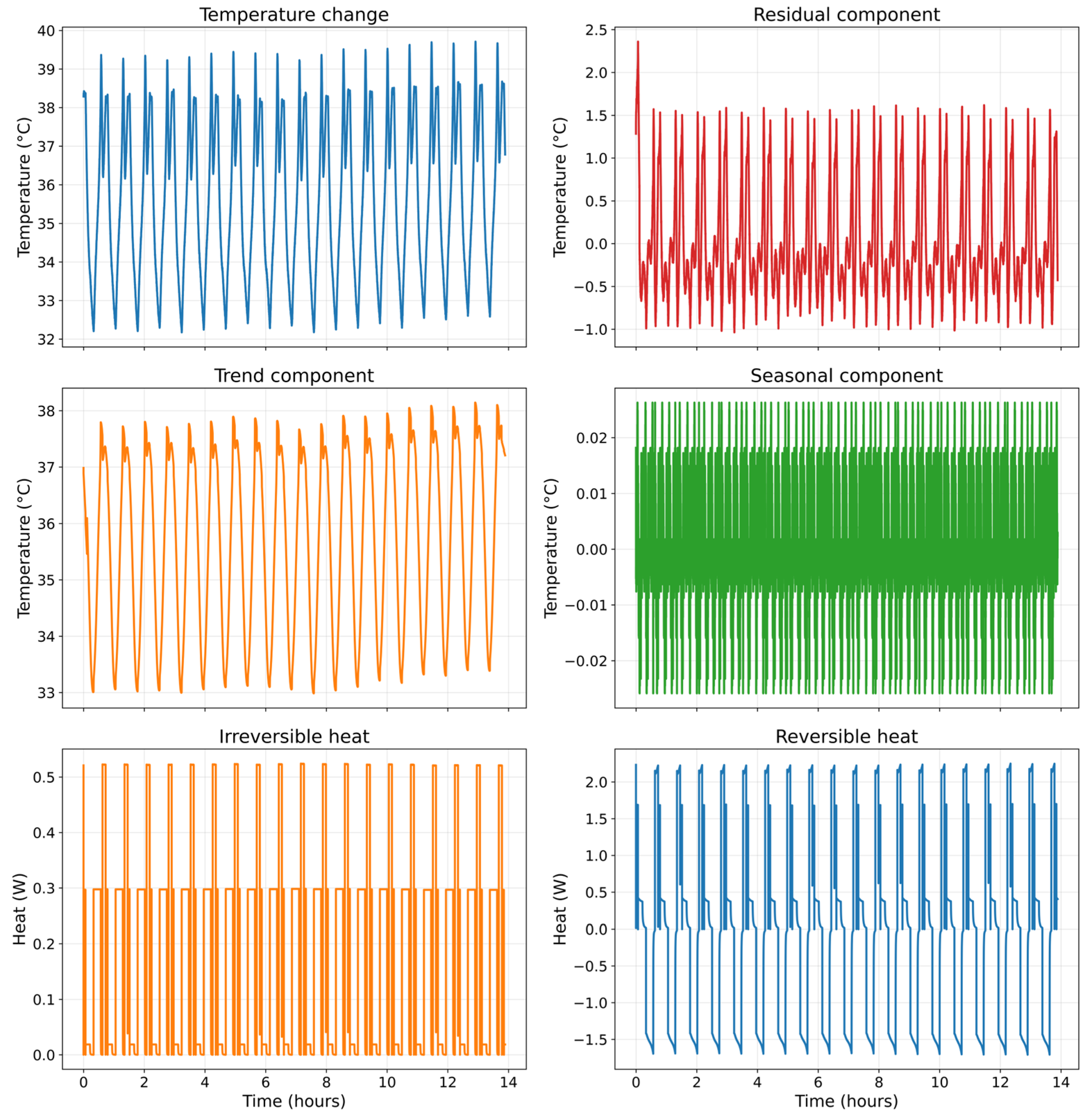

2.2. Temperature Decomposition, Heat-Generation Characterization, and Predictive Integration

2.3. Machine Learning and Deep Learning Predictive Framework

2.4. Machine Learning Regression Models

2.5. LSTM-Based Temporal Learning

2.6. Bidirectional Thermal Learning with BiLSTM

2.7. Adaptive Optimization Using Adam

2.8. Performance Metrics and Evaluation Strategy

2.9. Error Measurement and Reverse Temperature Scaling

2.10. Integrated Decomposition-Aware Predictive Formulations

2.11. Advanced Residual and Consistency Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Thermal Behavior Characterization and Data Conditioning

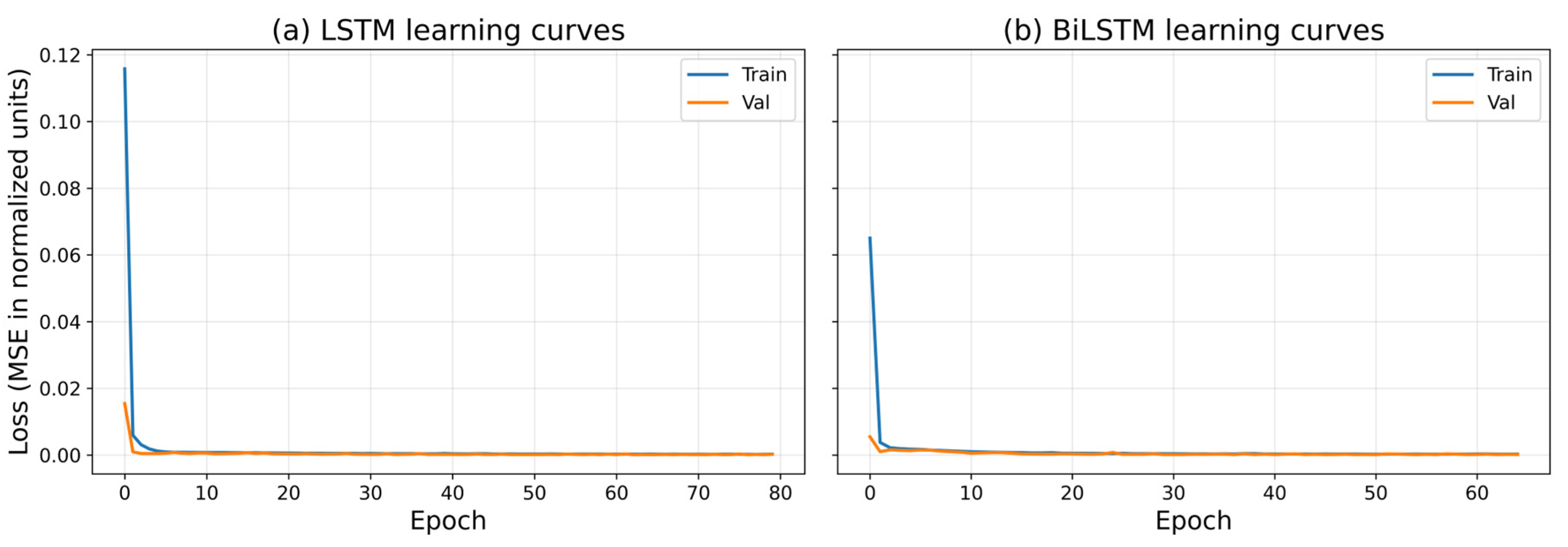

3.2. Model Learning Dynamics and Convergence Characteristics

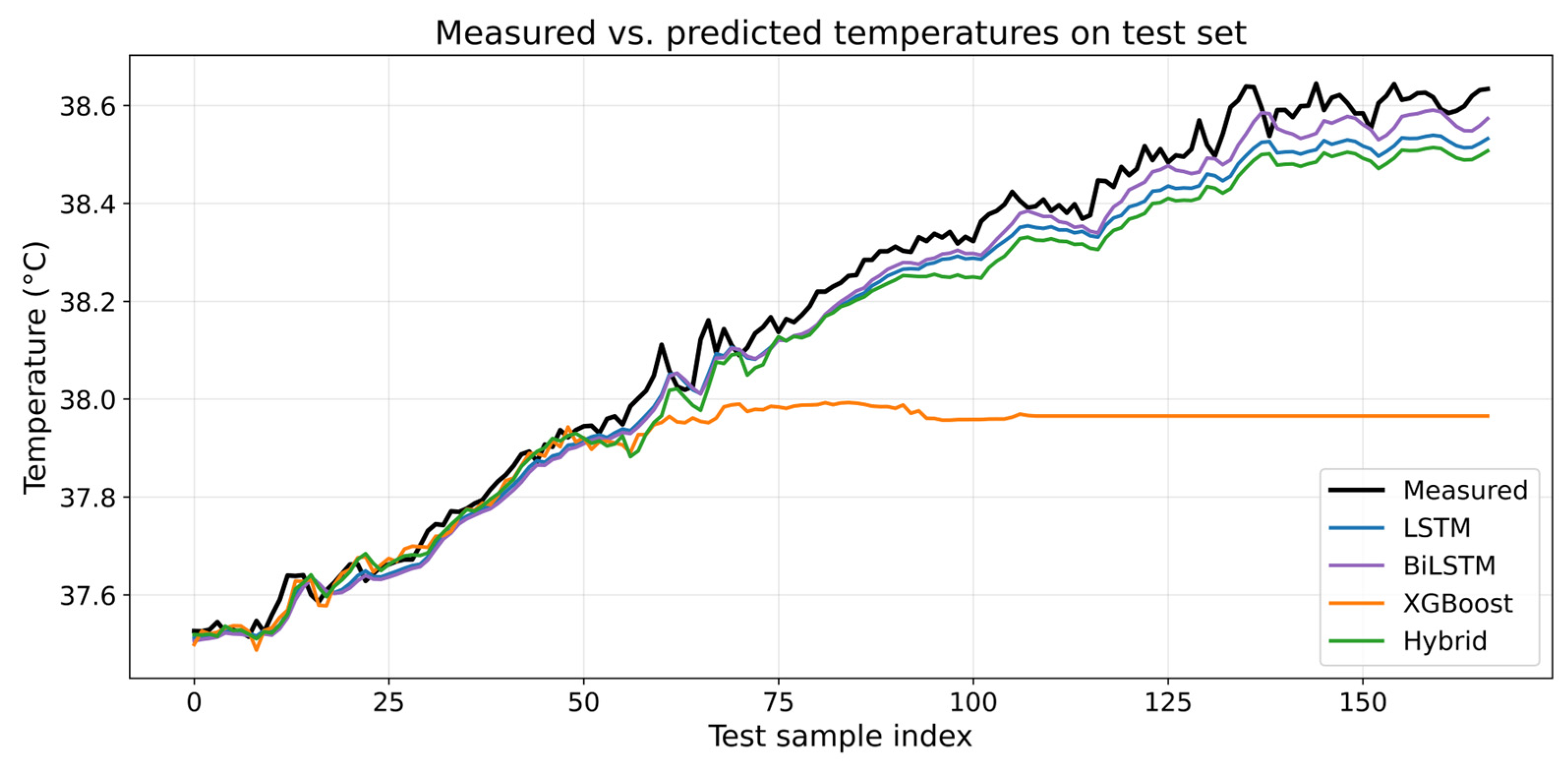

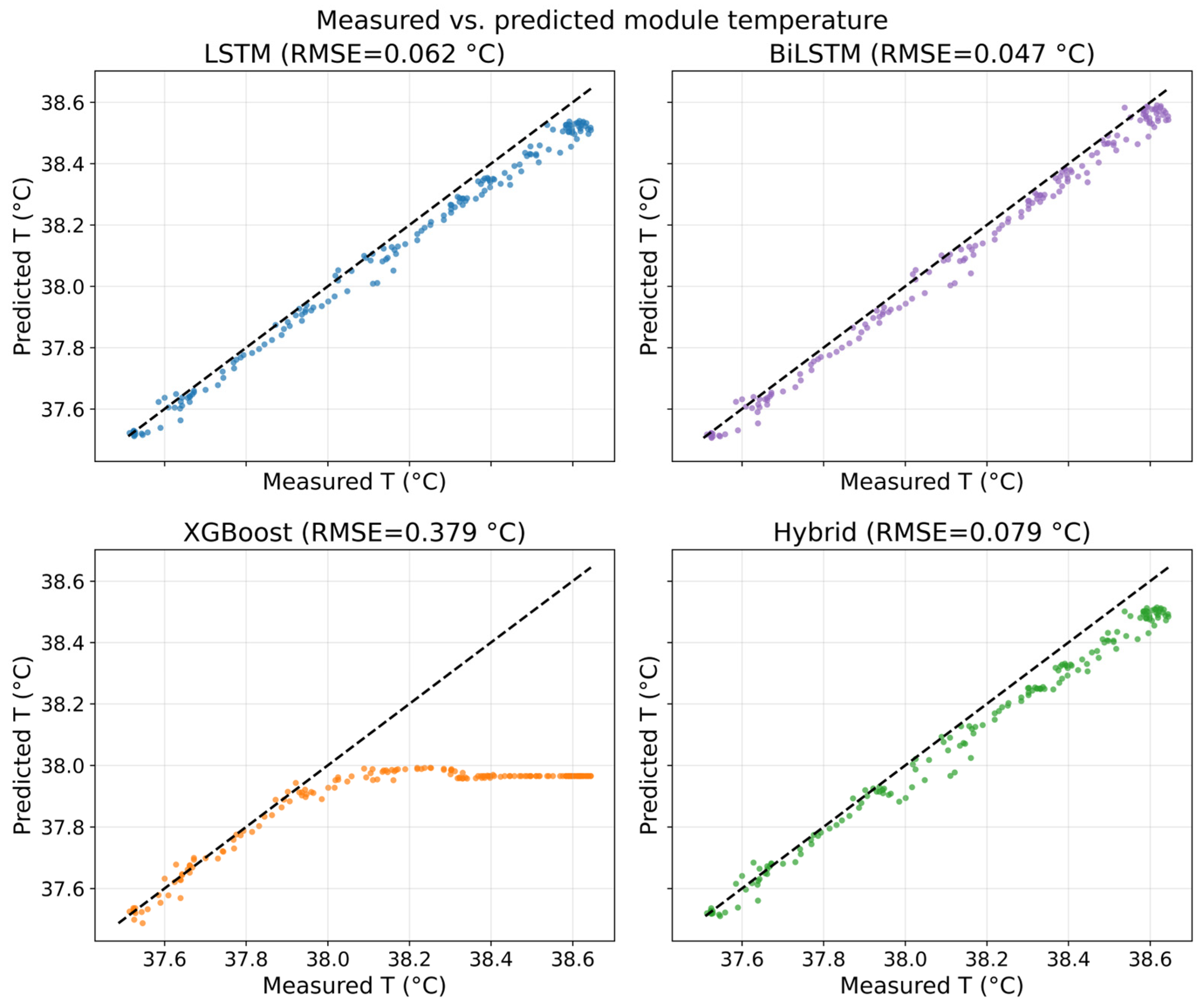

3.3. Predictive Fidelity Under Real Cycling Conditions

3.4. Worst-Case Electrothermal Response and Local Prediction Robustness

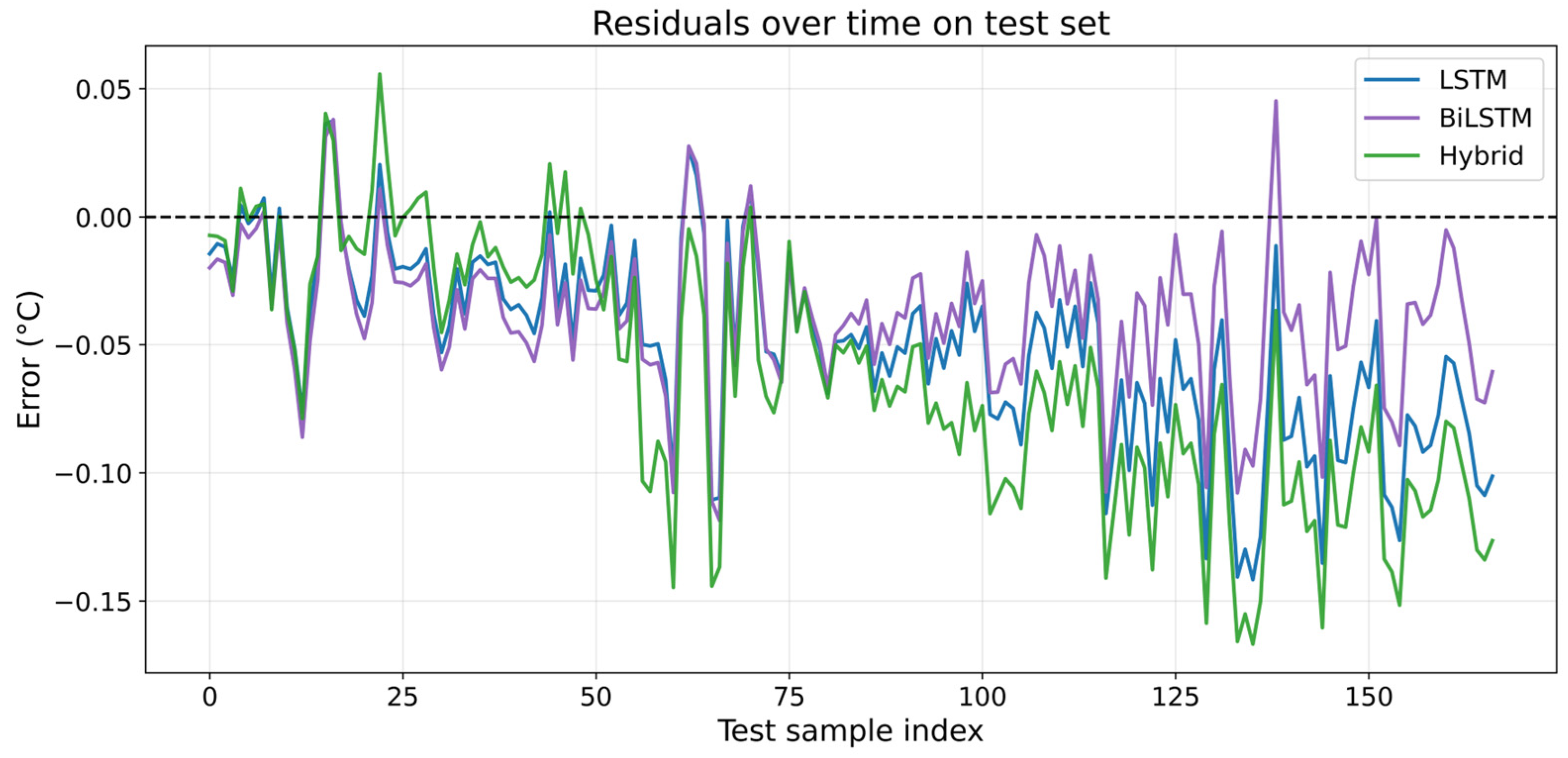

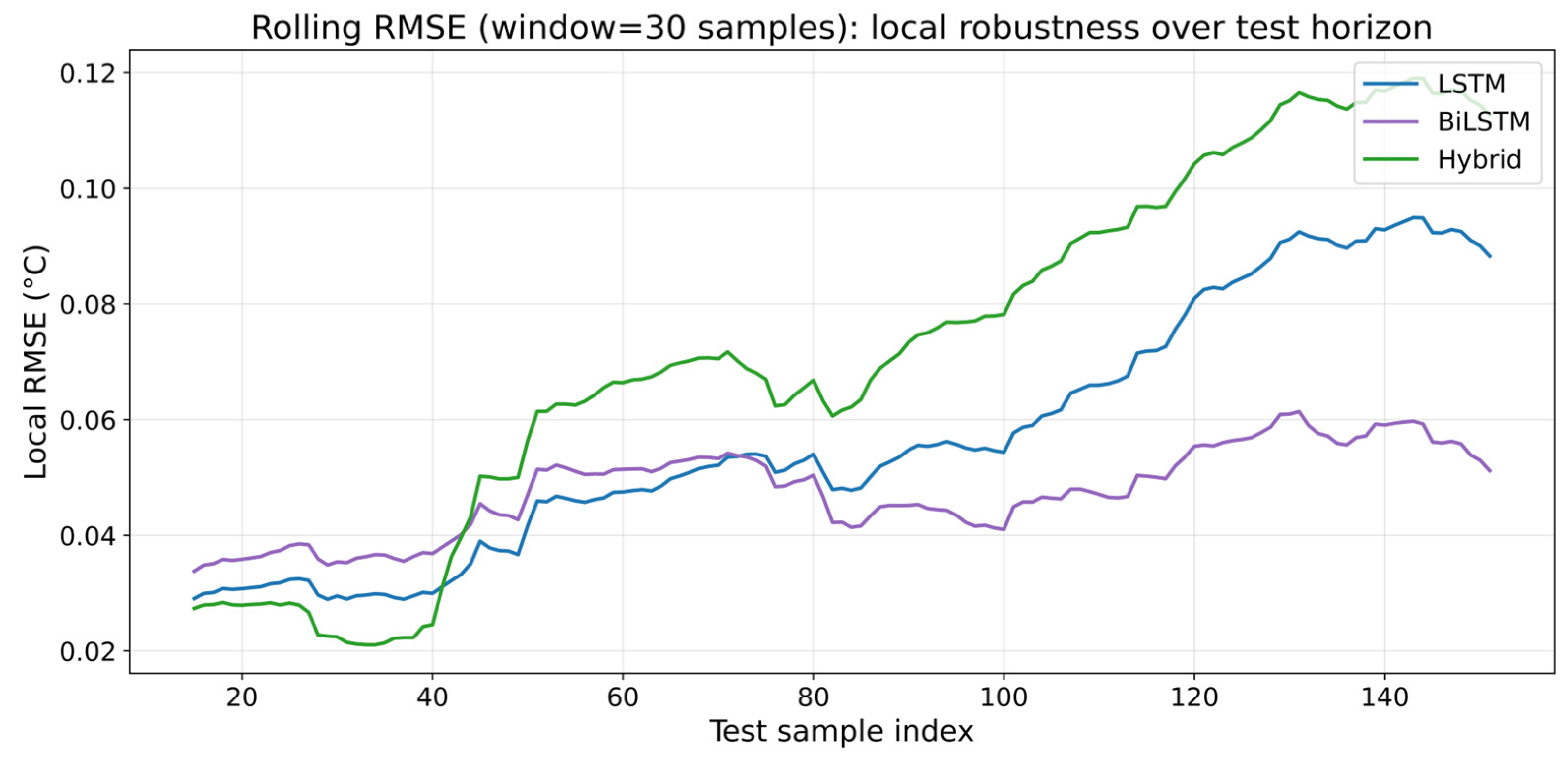

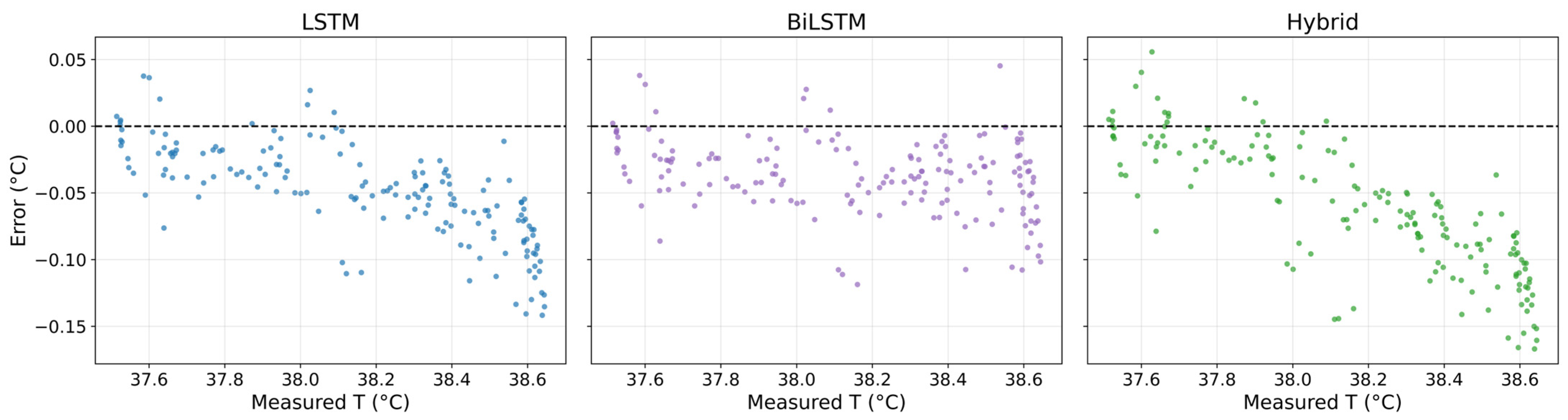

3.5. Residual Behavior and Temporal Consistency Assessment

3.6. Localized Robustness and Rolling Error Behavior

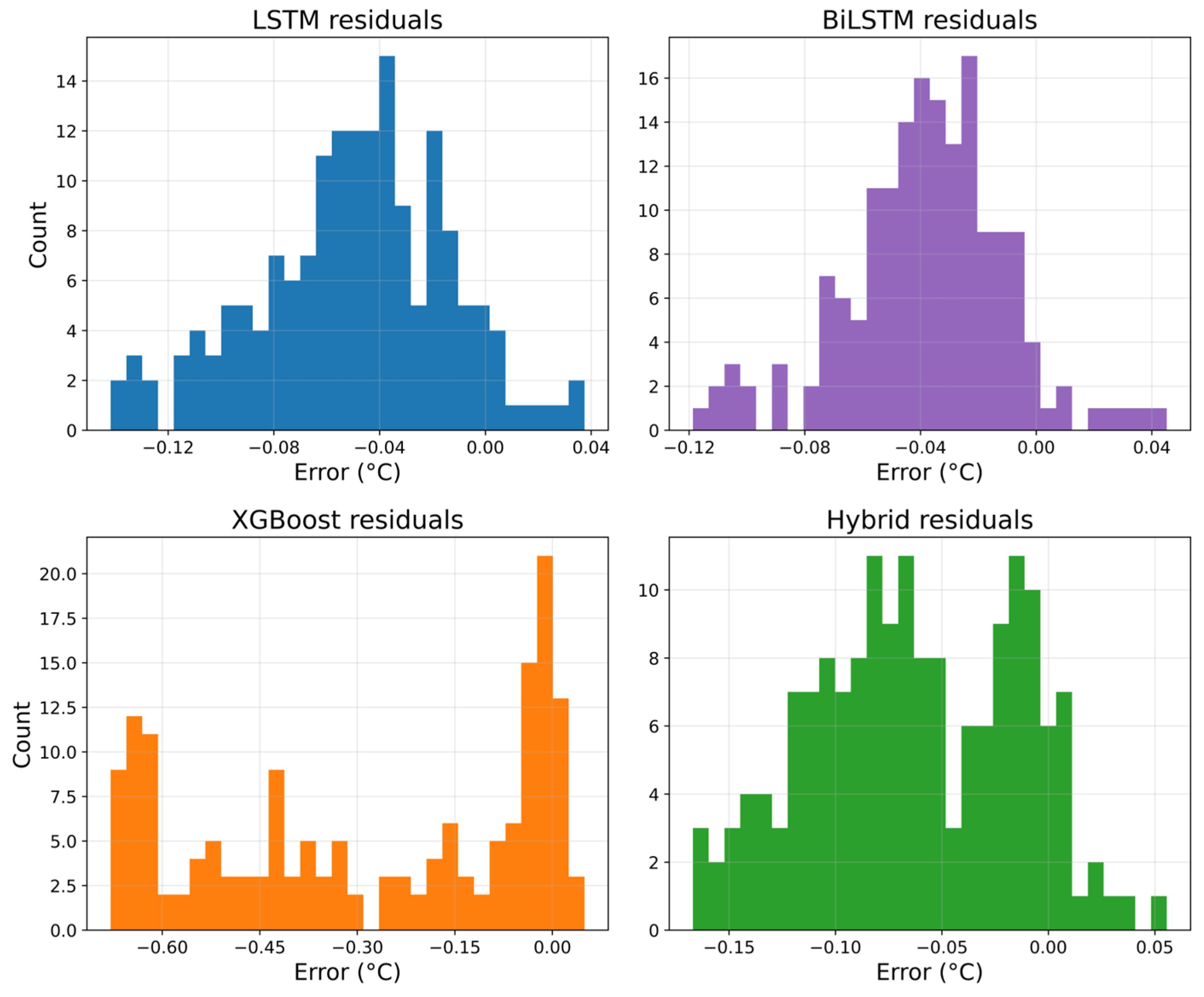

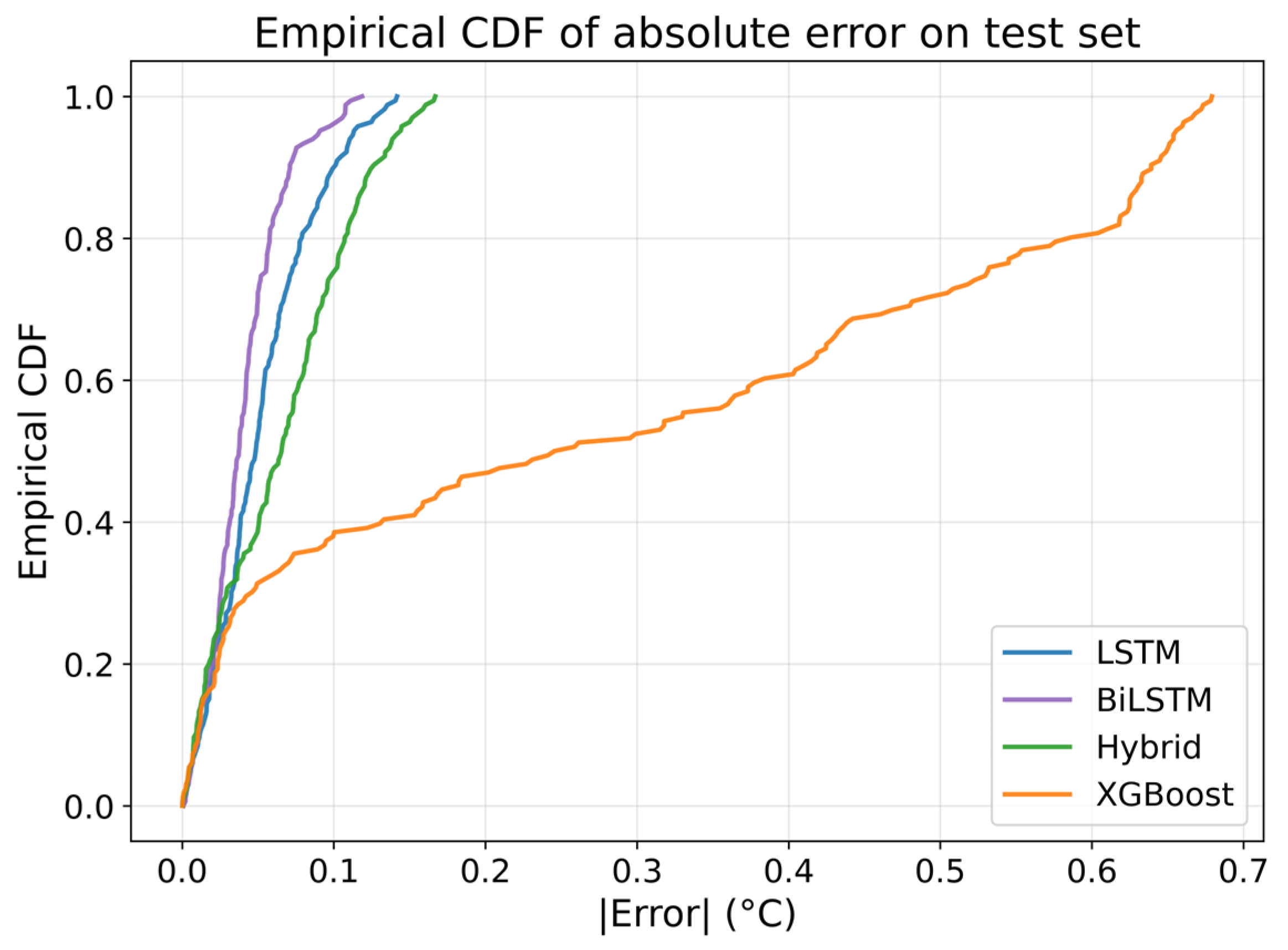

3.7. Error Distribution, Reliability, and Robustness Analysis

3.8. Comparative Insight Against Conventional Machine Learning Models

3.9. Implications for Predictive Thermal Management in BMS

3.10. Numerical Performance Summary and Quantitative Assessment

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Equation No. | Formula |

|---|---|

| (A1) | T(t) |

| (A2) | |

| (A3) | |

| (A4) | |

| (A5) | |

| (A6) | |

| (A7) | |

| (A8) | |

| (A9) | |

| (A10) | |

| (A11) | |

| (A12) | |

| (A13) | |

| (A14) | |

| (A15) | |

| (A16) | |

| (A17) | |

| (A18) | |

| (A19) | |

| (A20) | |

| (A21) | |

| (A22) | |

| (A23) | |

| (A24) | |

| (A25) | |

| (A26) | |

| (A27) | |

| (A28) | |

| (A29) | |

| (A30) | |

| (A31) | |

| (A32) | |

| (A33) | |

| (A34) | |

| (A35) | |

| (A36) | |

| (A37) | |

| (A38) | |

| (A39) | |

| (A40) | |

| (A41) | |

| (A42) | |

| (A43) | |

| (A44) | |

| (A45) | |

| (A46) | |

| (A47) | = |

| (A48) | |

| (A49) | |

| (A50) | |

| (A51) | R(t) |

| (A52) | |

| (A53) | |

| (A54) | |

| (A55) | |

| (A56) | |

| (A57) | |

| (A58) | |

| (A59) | |

| (A60) | |

| (A61) | |

| (A62) | |

| (A63) | |

| (A64) | |

| (A65) | |

| (A66) | |

| (A67) | |

| (A68) | |

| (A69) | |

| (A70) | |

| (A71) | |

| (A72) | |

| (A73) | |

| (A74) | |

| (A75) | |

| (A76) | |

| (A77) | |

| (A78) | |

| (A79) | |

| (A80) | |

| (A81) | |

| (A82) | |

| (A83) | |

| (A84) |

Appendix A.2

| Equation No. | Description |

|---|---|

| (A1) | Represents the raw measured battery temperature time series, serving as the foundational dataset from which all thermal trends, patterns, and predictive features are extracted. |

| (A2) | Identifies the minimum temperature within the dataset, establishing the lower normalization bound and preventing negative scaling artifacts. |

| (A3) | Determines the maximum recorded temperature, defining the upper normalization bound and ensuring normalized values remain bounded within ([0, 1]). |

| (A4) | Normalizes temperature samples to a unit interval, enhancing numerical conditioning, improving gradient stability during LSTM training, and enabling model comparability. |

| (A5) | Reconstructs temperatures in physical units (°C) from normalized predictions, ensuring interpretability and enabling direct comparison with measured values. |

| (A6) | Constructs fixed-length sequential input vectors, enabling temporal learning by capturing temperature dependencies across consecutive cycles. |

| (A7) | Defines the target output for one-step-ahead forecasting, directing the learning process toward next-cycle temperature prediction. |

| (A8) | Calculates the total number of valid sliding windows, thereby determining the effective supervised learning sample size. |

| (A9) | Allocates a specific proportion of samples to the training set, facilitating experimental evaluation under varying data-availability conditions. |

| (A10) | Computes the number of validation samples, ensuring an unbiased mechanism for hyperparameter tuning and generalization assessment. |

| (A11) | Extracts the thermal trend component via centered moving averaging, isolating slow, cumulative heat buildup within the cell. |

| (A12) | Forms the detrended temperature signal by removing long-term drift, enabling clearer discrimination of periodic heating effects. |

| (A13) | Produces intermediate cycle-aligned thermal values, capturing cyclic thermal oscillations linked to electrochemical operation. |

| (A14) | Establishes the mean seasonal pattern, representing the canonical periodic thermal response across multiple cycles. |

| (A15) | Derives the seasonal temperature component by centering transitional values, isolating reversible entropy-related oscillations. |

| (A16) | Extracts the residual component, encapsulating stochastic, non-periodic variations attributable to irreversible heating and measurement noise. |

| (A17) | Reconstructs the original temperature sequence from its trend, seasonal, and residual components, validating decomposition completeness. |

| (A18) | Quantifies reversible (entropic) heat generation arising from entropy changes during electrochemical reactions. |

| (A19) | Characterizes irreversible Joule heating caused by internal resistance, constituting the dominant driver of temperature rise under high loads. |

| (A20) | Aggregates reversible and irreversible heat terms, yielding the total heat generation profile underpinning observed temperature dynamics. |

| (A21) | Specifies the general form of a supervised regression model, establishing a mapping from input features to predicted temperatures. |

| (A22) | Computes Random Forest outputs through ensemble averaging, mitigating variance and improving robustness against measurement noise. |

| (A23) | Defines the Gradient Boosting framework, where successive weak learners iteratively refine residual prediction errors. |

| (A24) | Evaluates residuals used in boosting iterations, guiding weak learners toward systematic error correction. |

| (A25) | Formulates Support Vector Regression predictions in kernel space, enabling nonlinear modeling of temperature-cycle relationships. |

| (A26) | Implements the RBF kernel for SVR, enabling similarity measurement in high-dimensional feature space and capturing nonlinearity. |

| (A27) | Expresses additive-tree predictions used in XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost, enabling scalable learning over structured temporal data. |

| (A28) | Defines the squared-error loss objective, penalizing deviations between predicted and true normalized temperatures during optimization. |

| (A29) | Computes the LSTM input gate activation, regulating integration of new thermal information into the memory cell. |

| (A30) | Determines the forget gate activation, enabling selective retention or disposal of past thermal states. |

| (A31) | Governs the output gate transformation, controlling propagation of the internal cell state into the hidden layer. |

| (A32) | Produces the candidate cell state, supplying nonlinear thermal features prior to gated fusion. |

| (A33) | Updates the LSTM cell state by integrating retained memory and new information, supporting long-horizon pattern learning. |

| (A34) | Generates the hidden state from the updated cell state, providing the representational basis for temperature forecasting. |

| (A35) | Maps the hidden state to normalized temperature predictions in the model output layer. |

| (A36) | Computes forward hidden states in BiLSTM, encoding causal thermal dependencies from past measurements. |

| (A37) | Computes backward hidden states in BiLSTM, capturing temporal relationships extending into future measurements. |

| (A38) | Concatenates bidirectional features, enabling BiLSTM to exploit full temporal context for improved prediction accuracy. |

| (A39) | Produces the final BiLSTM temperature prediction from fused bidirectional states, leveraging cycle symmetry. |

| (A40) | Computes gradients of the loss with respect to parameters, initiating model weight updates. |

| (A41) | Updates the first-moment estimate of Adam, moderating oscillatory gradient behavior across cycles. |

| (A42) | Updates the second-moment estimate of Adam, adapting step sizes based on gradient variance. |

| (A43) | Applies bias correction to the first-moment estimate, stabilizing early optimization dynamics. |

| (A44) | Applies bias correction to the second-moment estimate, ensuring accurate scaling of parameter updates. |

| (A45) | Executes parameter updates using Adam, enabling efficient and stable convergence during deep learning training. |

| (A46) | Specifies the MSE loss in normalized space, providing a consistent objective for ML and DL model training. |

| (A47) | Converts predicted normalized temperatures to physical units, enabling real-world performance evaluation. |

| (A48) | Recovers true temperature values from normalized form, facilitating direct prediction error computation. |

| (A49) | Computes RMSE in °C, providing a scale-sensitive and interpretable accuracy metric for comparative analysis. |

| (A50) | Supplies measured current as a thermal excitation input, linking electrical load to thermal evolution. |

| (A51) | Provides internal resistance values required for irreversible heat estimation, reflecting cell health and aging. |

| (A52) | Introduces entropy coefficients, supporting reversible heat modeling grounded in thermodynamic principles. |

| (A53) | Evaluates reversible heat generation over time, enabling assessment of entropy-driven heating captured implicitly by the model. |

| (A54) | Quantifies irreversible heating dynamics, explaining monotonic temperature rise during sustained cycling. |

| (A55) | Computes intermediate seasonal averages, smoothing periodic variations before final seasonal extraction. |

| (A56) | Centers transitional thermal values, ensuring the seasonal component reflects unbiased periodicity. |

| (A57) | Represents the full sequence of LSTM hidden states, encoding long-range temporal dependencies. |

| (A58) | Defines the sigmoid activation, enabling nonlinear gating within the LSTM architecture. |

| (A59) | Specifies the tanh activation function, shaping candidate and output state dynamics. |

| (A60) | Denotes elementwise multiplication for gated integration within LSTM states. |

| (A61) | Formalizes the optimization objective minimized during model training. |

| (A62) | Defines the gradient-based rule used to update model parameters iteratively. |

| (A63) | Computes local median temperature, providing a robust baseline signal for noise reduction. |

| (A64) | Evaluates Median Absolute Deviation, enabling resilient quantification of variability. |

| (A65) | Establishes the Hampel outlier threshold, distinguishing anomalous thermal excursions. |

| (A66) | Substitutes aberrant measurements with median estimates, yielding a physically plausible cleaned time series. |

| (A67) | Determines the number of test samples, ensuring evaluation on unseen data. |

| (A68) | Quantifies prediction errors per sample in physical units, forming the core of post-training diagnostics. |

| (A69) | Measures absolute error magnitudes, supporting model comparison across prediction tasks. |

| (A70) | Computes MAE, summarizing average magnitude of prediction deviations. |

| (A71) | Calculates the coefficient of determination (R2), assessing variance explained by the model. |

| (A72) | Defines residuals between observed temperatures and LSTM predictions, serving as correction targets in hybrid modeling. |

| (A73) | Generates hybrid predictions by combining LSTM base forecasts with residual estimates from XGBoost. |

| (A74) | Constructs empirical CDF of absolute errors, enabling probabilistic reliability assessment. |

| (A75) | Computes rolling RMSE, facilitating localized performance evaluation over dynamic regimes. |

| (A76) | Identifies the index corresponding to maximum prediction error, revealing worst-case thermal behavior. |

| (A77) | Specifies generalized regression residuals, supporting comparative model diagnostics. |

| (A78) | Defines residual-learning targets, enabling XGBoost to correct systematic LSTM deficiencies. |

| (A79) | Sets window bounds for rolling RMSE analysis, preserving symmetry around an evaluation index. |

| (A80) | Formalizes the hybrid prediction structure as the sum of base and residual components. |

| (A81) | Restores original feature scale after normalization, reinstating physical interpretability. |

| (A82) | Computes train and validation sizes from user-defined ratios, enabling controlled dataset partitioning. |

| (A83) | Calculates RMSE directly from prediction errors, providing a standard measure of accuracy. |

| (A84) | Defines the indicator function for empirical CDF construction, enabling binary evaluation of tolerance compliance. |

Appendix A.3

| Symbols | Description |

|---|---|

| T(t) | Represents the measured battery temperature at time t. It is the primary time-series signal used for prediction, decomposition, and heat-generation analysis. |

| Minimum observed temperature in the dataset. Used as the lower bound for min-max normalization to avoid negative scaling. | |

| Maximum observed temperature in the dataset. Used as the upper bound for normalization and inverse scaling. | |

| Z(t) | Normalized temperature value at time t. Used as the input to ML/LSTM models to improve numerical stability during training. |

| L | Sequence/window length (e.g., 50 steps). Defines how many past temperature points are used to predict the next one. |

| Input sequence containing L consecutive normalized temperatures. Forms the training sample for forecasting models. | |

| True temperature target for the next timestep after the window x_n. Used to train models for one-step-ahead prediction. | |

| M | Total number of recorded temperature samples before segmentation. Used to determine available data length. |

| N | Total number of usable training windows after sequence extraction (N = M − L). Defines dataset size for supervised learning. |

| r | Train-validation split ratio. Controls how many windows become training data, enabling robustness analysis. |

| Number of training windows created based on ratio r. Used to train ML and LSTM/BiLSTM models. | |

| Number of validation windows. Used to evaluate generalization accuracy on unseen data. | |

| Long-term temperature trend estimated via moving average. Used to separate slow heat buildup from short-term fluctuations. | |

| Seasonal component representing periodic reversible temperature oscillations caused by cyclic charging/discharging. | |

| Residual component capturing non-seasonal, abrupt heating effects, noise, and irreversible Joule heating. | |

| f | Trend averaging window length. Determines the number of samples used to compute the smoothed temperature trend. |

| k | Half-window size for trend computation. Controls the symmetry of the moving average. |

| n | Number of cycles used to compute transitional seasonal patterns. |

| D(t) | De-trended temperature value (T−T_Trend). Used to isolate seasonal behavior from long-term thermal drift. |

| TS(t) | Transitional seasonal temperature component. Used for constructing periodic thermal patterns linked to cycle behavior. |

| Mean seasonal value. Used to center TS(t) and remove bias from seasonal estimation. | |

| Reversible heat generated due to entropy change during electrochemical reactions. Helps interpret reversible temperature oscillations. | |

| Irreversible (Joule) heat caused by internal resistance and current flow. Key indicator of thermal stress and degradation. | |

| Total heat generation (q_rev + q_irr). Used to validate the physical consistency of predicted temperature trends. | |

| I(t) | Measured current at time t. Primary driver of reversible and irreversible heat-generation mechanisms. |

| R(t) | Internal resistance of the battery at time t. Used to compute irreversible heating, especially at high load. |

| Entropy coefficient of open-circuit voltage. Used to compute reversible heat as temperature varies. | |

| f(.) | General machine learning prediction function. Represents regression mapping from input sequences to temperature forecasts. |

| (.) | Individual decision tree in a Random Forest. Each tree contributes to the final temperature prediction. |

| (.) | Gradient Boosting ensemble model after M trees. Represents incremental improvement by fitting residuals. |

| Residual error at boosting iteration m. Used to determine what the next tree must learn. | |

| Dual coefficients in Support Vector Regression. Determine the influence of support vectors in predictions. | |

| K(x,z) | Kernel function (e.g., RBF). Measures similarity between temperature sequences for SVR models. |

| (.) | Tree functions in XGBoost/LightGBM/CatBoost. Each adds predictive corrections to improve temperature estimation. |

| Loss function comparing predicted and true values. Drives optimization of regression models. | |

| Temperature input at timestep t to LSTM/BiLSTM. Forms the sequential data fed into the recurrent network. | |

| LSTM hidden state at time t. Encodes compressed temporal temperature information. | |

| LSTM cell state. Stores long-term temperature dependencies and retention patterns across cycles. | |

| LSTM input gate. Controls how much new thermal information is added to memory. | |

| LSTM forget gate. Controls removal of outdated historical temperature information. | |

| LSTM output gate. Determines how much of memory contributes to next hidden state. | |

| Candidate cell state. Represents new nonlinear temperature information before gating. | |

| Input weight matrices for LSTM gates. Map temperature input features into gating operations. | |

| Recurrent weight matrices. Capture temporal influence of past hidden states in LSTM dynamics. | |

| Bias vectors for each LSTM gate. Adjust gating activation thresholds. | |

| Dense-layer output matrix that maps LSTM hidden state to predicted temperature. | |

| Output bias term for generating final prediction. | |

| Forward hidden state in BiLSTM. Learns temperature patterns based on past context. | |

| Backward hidden state. Learns future-driven thermal correlations, improving cycle-symmetry learning. | |

| BiLSTM fused hidden state. Combines forward and backward states for richer representations. | |

| Gradient of the loss at time t. Used during backpropagation to update network weights. | |

| Adam optimizer’s first-moment estimate (mean of gradients). Smooths learning updates. | |

| Adam second-moment estimate (variance of gradients). Stabilizes step size for irregular signals. | |

| Bias-corrected first moment. Fixes initial bias when gradients are small. | |

| Bias-corrected second moment. Ensures correct scaling of updates early in training. | |

| θ | Model parameters being learned (weights and biases). Updated iteratively during training. |

| α | Learning rate. Controls step size for parameter updates. |

| Decay rate for first-moment estimation in Adam. Governs memory of past gradients. | |

| Decay rate for second-moment estimation. Smooths squared gradient accumulation. | |

| ε | Numerical stability constant to prevent division by zero. |

| σ(.) | Sigmoid activation function. Used in LSTM gates for controlling information flow. |

| tanh(.) | Hyperbolic tangent activation. Adds nonlinearity to LSTM internal state transitions. |

| ⊙ | Elementwise (Hadamard) product. Core operator in LSTM gate computations. |

| Loss function minimized during learning, typically MSE for regression models. | |

| Predicted normalized temperature value for sample i. Output of ML/DL model. | |

| True normalized temperature target. Basis for computing prediction error. | |

| Predicted temperature in °C after inverse scaling. Used for physical interpretation. | |

| Actual temperature in °C. Used to compute real-world performance metrics. | |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error. Primary optimization objective during model training. |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error in °C. Used to compare ML and DL predictive accuracy. |

| Full sequence of hidden states produced by LSTM/BiLSTM. Encodes all temperature dynamics observed across the window. |

References

- Tarascon, J.-M.; Armand, M. Issues and challenges facing rechargeable lithium batteries. Nature 2001, 414, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani, S.S.; Shabeer, Y.; Allard, F.; Fowler, M.; Ziebert, C.; Wang, Z.; Panchal, S.; Chaoui, H.; Mekhilef, S.; Dou, S.X.; et al. A Comprehensive Review on Lithium-Ion Battery Lifetime Prediction and Aging Mechanism Analysis. Batteries 2025, 11, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.M.; Demirocak, D.E. Degradation mechanisms in Li-ion batteries: A state-of-the-art review. Int. J. Energy Res. 2017, 41, 1963–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabeer, Y.; Madani, S.S.; Panchal, S.; Mousavi, M.; Fowler, M. Different Metal–Air Batteries as Range Extenders for the Electric Vehicle Market: A Comparative Study. Batteries 2025, 11, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Ouyang, M.; Liu, X.; Lu, L.; Xia, Y.; He, X. Thermal runaway mechanism of lithium ion battery for electric vehicles: A review. Energy Storage Mater. 2018, 10, 246–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mevawalla, A.; Shabeer, Y.; Tran, M.K.; Panchal, S.; Fowler, M.; Fraser, R. Thermal Modelling Utilizing Multiple Experimentally Measurable Parameters. Batteries 2022, 8, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani, S.S.; Shabeer, Y.; Nair, A.S.; Fowler, M.; Panchal, S.; Ziebert, C.; Chaoui, H.; Dou, S.X.; See, K.; Mekhilef, S.; et al. Advances in Battery Modeling and Management Systems: A Comprehensive Review of Techniques, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Batteries 2025, 11, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani, S.S.; Allard, F.; Shabeer, Y.; Fowler, M.; Panchal, S.; Ziebert, C.; Mekhilef, S.; Dou, S.X.; See, K.; Wang, Z. Exploring the Aging Dynamics of Lithium-Ion Batteries for Enhanced Lifespan Understanding. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2025, 2968, 012017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Ma, E.W.M.; Tsui, K.L.; Pecht, M. Battery Management Systems in Electric and Hybrid Vehicles. Energies 2011, 4, 1840–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani, S.S.; Shabeer, Y.; Fowler, M.; Panchal, S.; Chaoui, H.; Mekhilef, S.; Dou, S.X.; See, K. Artificial Intelligence and Digital Twin Technologies for Intelligent Lithium-Ion Battery Management Systems: A Comprehensive Review of State Estimation, Lifecycle Optimization, and Cloud-Edge Integration. Batteries 2025, 11, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Liu, C.; Zhao, T.; Kuang, Y.; Yin, B.; Yuan, R.; Song, L. Review—Online Monitoring of Internal Temperature in Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2023, 170, 057517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Ruan, H.; Sun, B.; Zhang, W.; Gao, W.; Wang, L.Y.; Zhang, L. A reduced low-temperature electro-thermal coupled model for lithium-ion batteries. Appl. Energy 2016, 177, 804–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harippriya, S.; Vigneswaran, E.E.; Jayanthy, S. Battery Management System to Estimate Battery Aging using Deep Learning and Machine Learning Algorithms. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2325, 012004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Rivera, A.; Wu, D. Battery health management using physics-informed machine learning: Online degradation modeling and remaining useful life prediction. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 179, 109347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Wen, J.; Yang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zeng, J. State-of-Health Prediction of Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on CNN-BiLSTM-AM. Batteries 2022, 8, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Huang, J.; Cai, W.; Marco, J. Li-ion battery temperature estimation based on recurrent neural networks. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2021, 64, 1335–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, S.; Ahamed, F.; Ghosh, S.; Roy, T. KAN-Therm: A Lightweight Battery Thermal Model Using Kolmogorov-Arnold Network. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.09145. [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva, C.M.; Akula, R.; Amon, C.H. Challenges and Opportunities in Hierarchical Multi-Length-Scale Thermal Modeling of Electric Vehicle Battery Systems. J. Heat Transf. 2025, 147, 124701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Ba, Z.; Sun, L. Physics-informed neural networks in heat transfer-dominated multiphysics systems: A comprehensive review. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 157, 111098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, V. Machine Learning Enhancement of Heat Transfer Research and Technology Development. Annu. Rev. Heat Transf. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawi, A.; Saeed, A.; Sharqawy, M.H.; Al Janaideh, M. A Comprehensive Review of Thermal Management Challenges and Safety Considerations in Lithium-Ion Batteries for Electric Vehicles. Batteries 2025, 11, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xiang, H.; Xiong, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z. Benchmarking core temperature forecasting for lithium-ion battery using typical recurrent neural networks. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 248, 123257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.; Cui, N.; Lu, D.; Li, C. Temperature prediction of lithium-ion battery based on adaptive GRU transfer learning framework considering thermal effects decomposition characteristics. Energy 2025, 322, 135504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, K.; Xu, W.; Lai, X.; Li, D.; Meng, X.; Zheng, Y.; Feng, X. Physics-informed machine learning estimation of the temperature of large-format lithium-ion batteries under various operating conditions. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 269, 126200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, G.; Zhu, D.; Campbell, J.J.; Wang, M. An LSTM-PINN Hybrid Method to Estimate Lithium-Ion Battery Pack Temperature. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 100594–100604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamati, S.; Chaoui, H.; Gualous, H. Enhancing Battery Thermal Management With Virtual Temperature Sensor Using Hybrid CNN-LSTM. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2024, 10, 10272–10287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.H.; Bukhari, S.M.S.; Houran, M.A.; Mansoor, M.; Khan, N.M.; Sanfilippo, F. DeepTimeNet: A novel architecture for precise surface temperature estimation of lithium-ion batteries across diverse ambient conditions. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 61, 105002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiong, C.; Wang, Y.; Xu, P.; Ju, C.; Shi, J.; Yang, G.; Chu, J. Temperature state prediction for lithium-ion batteries based on improved physics informed neural networks. J. Energy Storage 2023, 73, 108863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surya, S.; Samanta, A.; Marcis, V.; Williamson, S. Hybrid Electrical Circuit Model and Deep Learning-Based Core Temperature Estimation of Lithium-Ion Battery Cell. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2022, 8, 3816–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Li, P.; Cao, W.; Chen, H.; Wang, W.; Yu, Y.; He, H. Machine learning-based hybrid thermal modeling and diagnostic for lithium-ion battery enabled by embedded sensing. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 216, 119059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Li, P.; Shao, L.; Shui, M.; Wang, D.; Long, N.; Ren, Y.; Shu, J. Lithium barium titanate: A stable lithium storage material for lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2015, 278, 546–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H.; Wu, L.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, K. Physics-informed neural network approach for heat generation rate estimation of lithium-ion battery under various driving conditions. J. Energy Chem. 2022, 78, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Che, Y.; Hu, X.; Sui, X.; Teodorescu, R. Sensorless Temperature Monitoring of Lithium-Ion Batteries by Integrating Physics With Machine Learning. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2023, 10, 2643–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Xiong, C.; Du, X. Study on Real-Time Battery Temperature Prediction Based on Coupling of Multiphysics Fields and Temporal Networks. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 105511–105526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, P.; Deng, Y.; Li, B. The Lithium-Ion Battery Temperature Field Prediction Model Based on CNN-Bi-LSTM-AM. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, J.; Sun, X.; Wei, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, B.; Liu, C.; Lu, H. A physics-guided method for predicting the core temperature of lithium-ion batteries. Energy 2025, 337, 138649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Tahhan, A.; Ramadan, M.; Choi, D.S.; Ahmed, R.; Ghazal, M.; AlKhedher, M. Recent advancements in Artificial Neural Network-based temperature prediction and management of lithium-ion batteries: A comprehensive review. AI Therm. Fluids 2025, 4, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonka, K.M.; Schwaller, P.; Ortega-Guerrero, A.; Smit, B. Leveraging large language models for predictive chemistry. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2024, 6, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velumani, D.; Bansal, A. Thermal Behavior of Lithium- and Sodium-Ion Batteries: A Review on Heat Generation, Battery Degradation, Thermal Runway—Perspective and Future Directions. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 14000–14029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; He, C.; Zhao, N.; Sha, J. Data-driven analysis on thermal effects and temperature changes of lithium-ion battery. J. Power Sources 2021, 482, 228983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelly, T.J.; Weibel, J.A.; Ziviani, D.; Groll, E.A. Comparative analysis of battery electric vehicle thermal management systems under long-range drive cycles. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 198, 117506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, A.; Özdemir, T.; Ekici, Ö.; Başlamışlı, S.Ç.; Köksal, M. A thermal model for Li-ion batteries operating under dynamic conditions. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 185, 116338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorogush, A.V.; Ershov, V.; Yandex, A.G. CatBoost: Gradient Boosting with Categorical Features Support. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.11363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severson, K.A.; Attia, P.M.; Jin, N.; Perkins, N.; Jiang, B.; Yang, Z.; Chen, M.H.; Aykol, M.; Herring, P.K.; Fraggedakis, D.; et al. Data-driven prediction of battery cycle life before capacity degradation. Nat. Energy 2019, 4, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Madani, S.S.; Shabeer, Y.; Fowler, M.; Panchal, S.; Ziebert, C.; Chaoui, H.; Allard, F. Physics-Informed Temperature Prediction of Lithium-Ion Batteries Using Decomposition-Enhanced LSTM and BiLSTM Models. World Electr. Veh. J. 2026, 17, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj17010002

Madani SS, Shabeer Y, Fowler M, Panchal S, Ziebert C, Chaoui H, Allard F. Physics-Informed Temperature Prediction of Lithium-Ion Batteries Using Decomposition-Enhanced LSTM and BiLSTM Models. World Electric Vehicle Journal. 2026; 17(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj17010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleMadani, Seyed Saeed, Yasmin Shabeer, Michael Fowler, Satyam Panchal, Carlos Ziebert, Hicham Chaoui, and François Allard. 2026. "Physics-Informed Temperature Prediction of Lithium-Ion Batteries Using Decomposition-Enhanced LSTM and BiLSTM Models" World Electric Vehicle Journal 17, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj17010002

APA StyleMadani, S. S., Shabeer, Y., Fowler, M., Panchal, S., Ziebert, C., Chaoui, H., & Allard, F. (2026). Physics-Informed Temperature Prediction of Lithium-Ion Batteries Using Decomposition-Enhanced LSTM and BiLSTM Models. World Electric Vehicle Journal, 17(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj17010002