Department of Veterans Affairs’ Transportation System: Stakeholder Perspectives on the Current and Future System, Including Electric Autonomous Ride-Sharing Services

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Ethics

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Participants

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats (SWOT) as a Framework

2.6. Data Collection and Data Management

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Semi-Structured Interview Data

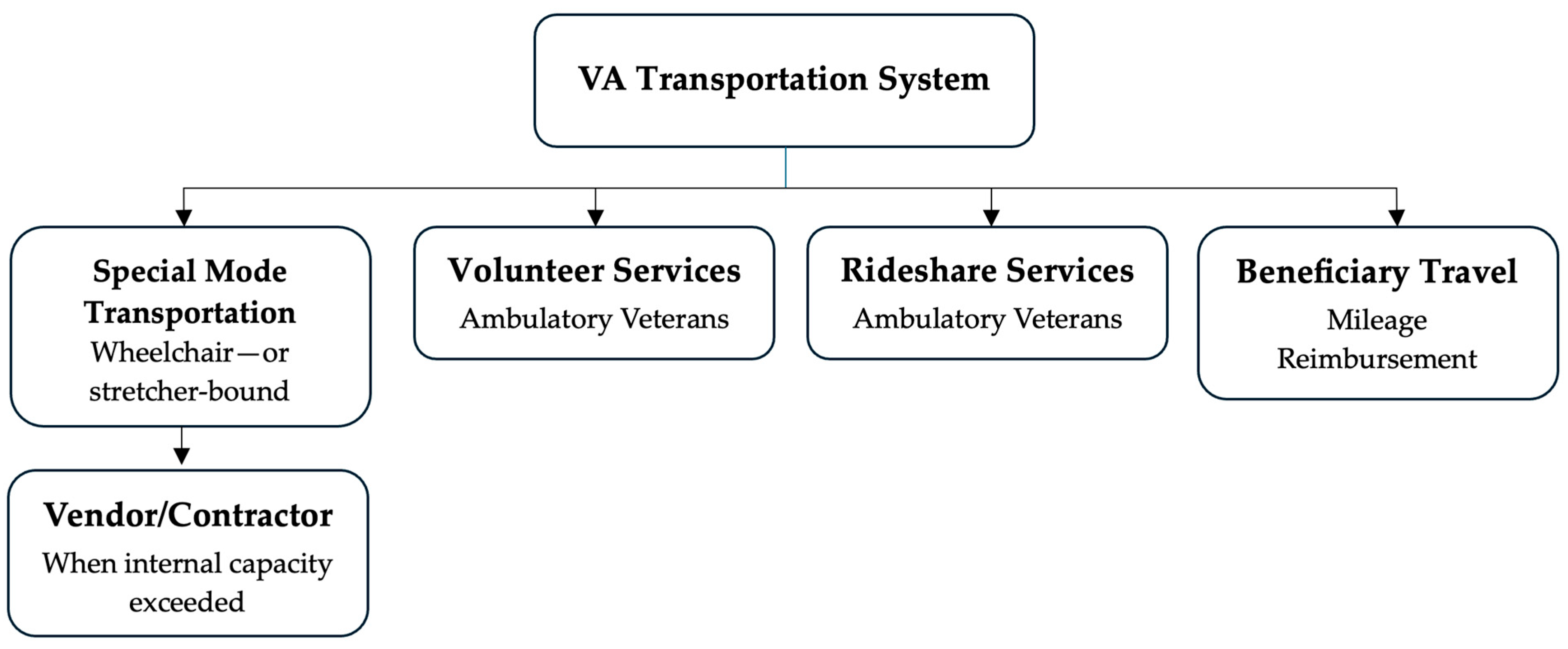

3.2.1. Complex System

“Special mode, part of the medical administration service, handles wheelchair and stretcher-bound transport…providing door-to-door service…special mode has the secondary option of vending (ID: 1010).”

“[Volunteer Services] I can’t allow non-ambulatory individuals on the vehicle. We don’t have a ramp, lifting device, or any moving equipment, and my volunteers are certainly not medical staff (ID: 1012).”

“We partnered with Uber to provide transportation for ambulatory veterans—those who can walk and self-assist. Before that, they only had mileage reimbursement. [Beneficiary Travel] To qualify, you have to meet certain criteria, you got to be service connected, at least 30% pension, and have an income below $16,500. Not every Veteran qualifies (ID: 1004).”

“Everything else is vented out to a contractor. Trips cannot be vended if the individual does not meet special mode criteria (ID: 1006).”

“There are so many regulatory components to transportation that oftentimes there’s more services available than is known. And there’s different requests for adjustments of regulations to open coverage that’s going through the congressional process (ID: 1000).”

“If you join VTS and sign up 100%, take their money and their vehicles, then you have to do everything exactly as they say. That doesn’t work for our area. Our leadership is more like, ‘do what you got to do to get these folks in and take them home’ (ID: 1006).”

“The clinical inpatient team determines whether a Veteran is ambulatory or requires a wheelchair or stretcher. This information is then communicated to the social worker, who completes a trip ticket specifying the transportation needs—such as requiring oxygen, a stretcher, or a wheelchair (ID: 1014).”

“[Office of Rural Health] We help provide the funding and the VTS provides vehicle support for the personnel to get them up and running (ID: 1000).”

“[Veterans Experience Office] Drills down on all transportation complaints and issues (ID: 1006).”

“It comes down to stakeholders sitting down with leadership at the division or facility level and making the case—being able to show, based on data, the resource impact both financially, by reducing spending on third-party contractors and ambulances, and operationally, by improving access to care for Veterans in high-need areas (ID: 1008).”

“We piloted a rural shuttle based on identified need in Levy, Gilchrist, and Dixie counties. After six months of outreach and advertising, we received only one (non-legitimate) call. It never really got off the ground. I know there’s a need, but when it comes down to it, it’s hard to get folks to do it (ID1006).”

“One barrier with Uber and Lyft is that Veterans need a smartphone, and that’s not always the case with older generations (ID: 1006).”

“If a Veteran is very poor, has a car that doesn’t work, or lives 3 h away from a specialty care appointment without a friend or family member to assist, they might not be eligible for mileage reimbursement or Uber if they’re not ambulatory. And that can potentially cause further health concerns for that Veteran if they’re not getting the care they need. I would love it if the VA could say every Veteran gets a ride to every appointment, but some of our areas are very rural. Even if the Veteran is eligible for Beneficiary or special mode travel, there might not be a vendor who’s available to go to those more rural areas (ID: 1014).”

3.2.2. Transportation Strengths

“The NFLSGA is like no other facility and should be its own service because we’re that big (ID: 1006).”

“We are very flexible. If a need arises that we wouldn’t typically support, we reassess and find a way to help, considering the long-term impact. For example, if a patient from the Panhandle had surgery in Gainesville and initially had transportation but now needs it for a follow-up appointment, we may classify it as a one-time or until the need is over (ID: 1010).”

“Because of the integrated nature of VA care, the collaboration between the transportation program and social work provides better coordinated care, especially in terms of identifying and addressing the social determinants of health (ID: 1002).”

“The ORH and the VTP work really well together. We both recognize how important the other is, and that’s a real strength (ID: 1000).”

“Provides door-to-door service, offering one-on-one support between the Veteran and VA staff. It is also probably tracked better (ID: 1006).”

“Many of our Veterans are disabled, and not all disabilities are visible. It’s great that we have resources for both seen and unseen disabilities, something not always available to non-Veterans (ID: 1014).”

“There is diversity within the system, with staff-operated, volunteer-operated, and third party-operated systems providing coverage (ID: 1012).”

“The program is primarily staffed by Veterans. They have a commitment to service and to other Veterans, and because they are Veterans, they bring military experience in transportation, logistics, program management, and personnel management. It’s unique—it’s truly a Veteran-owned and Veteran-operated entity within the VA (ID: 1002).”

“The support of Veterans as drivers—by connecting and being the inspiration for a Veteran to get to an appointment or providing added comfort for them to go—is really impressive and impactful (ID: 1000).”

“We monitor all training and driver physicals; they’re held to a higher standard (ID: 1006).”

3.2.3. Transportation Weaknesses

“We always need more resources—manpower, vehicles—because the demand is overwhelming. Right now, we’re in a budget crunch, and everything is pretty much frozen. Part of the reason is community care—if a Veteran can’t be seen within 30 days, we have to outsource it, and the VA covers the cost. That’s gotten very expensive—just in NFLSGA, it’s about $700 million (ID: 1004).”

“It comes down to staffing. Each morning, we get a list of 25–35 Veterans needing rides, but we only have two drivers. They can manage four to six trips a day, with three passengers each…and people have to understand that schedule changes daily, it’s driven by patient appointment (ID: 1006).”

“One of the biggest weaknesses is staffing. Due to a neutral FTE policy and limited funding, transportation often gets overlooked in the broader healthcare conversation. Leadership may prioritize hiring 25 doctors, but without drivers, patients can’t get to their appointments—and personnel is usually the first area cut (ID: 1008).”

“The problem with volunteers is consistency. I love them all and plan to volunteer myself, but when they’re unreliable, it disrupts patient appointments (ID: 1006).”

“If a volunteer goes on vacation for three months, which happens quite regularly, we don’t have a built-in backup (ID: 1012).”

“DAV offers a great shuttle service, but it’s not run through us. It used to be robust—vans ran daily between Jacksonville and Gainesville—but after COVID-19, volunteer numbers dropped significantly. Most volunteers are 60+, and once COVID-19 came through, I think it spooked them. Now, they don’t always have the people to keep the vans running daily, and gaps are starting to show in our coverage (ID: 1010).”

“There’re administrative and clinical criteria that have to be met for Veterans to be eligible for that program, and that can sometimes affect a Veteran’s access to care (ID: 1014).”

“We can do a better job communicating the criteria of what makes a Veteran eligible for certain programs within the VA, specifically regarding transportation (ID: 1014).”

3.2.4. Autonomous Ride-Sharing Service Opportunities

“It would open up the pool of employees that could successfully help with the transportation, so that would be helpful (ID: 1000).”

“It would provide a better resource for Veterans to have that consistent point of access in a city or town…all they have to do is show up to one of the stops, get on and away they go (ID: 1008).”

“It would be good if it could help rural Veterans get to their final urban track of their ride to make that standardized and less stressful (ID: 1000).”

“On a smaller scale, we could use it within the hospital. Our campus is large, and we have many Veterans—some with disabilities, others just running late—who could benefit from quick hop-on, hop-off routes. It could also support parking access and even help employees navigate the hospital and nearby locations more easily (ID: 1004).”

“Knowing they can be geofenced, ARSS would be especially beneficial in large metropolitan areas where maintenance is easier and connectivity is stronger due to widespread cell tower coverage (ID: 1008).”

“In large, walkable developments or Veteran communities, ARSS could go beyond medical appointments to support trips for groceries, dining, physical activity, and access to parks—addressing broader social determinants like food, education, and healthcare access (ID: 1002).”

3.2.5. Autonomous Ride-Sharing Service Threats

“Their trips are so varied that it’s hard to establish a shuttle on a standardized route. For Level 4, it would need to stay close to the VA, with specific geographical constraints. Rural Veterans have such varied road conditions, distances, and terrain… it’s going to be the topography that impacts distance (ID: 1000).”

“It’s being run on satellites or some kind of tower control—is that going to be an issue in rural areas? (ID: 1010).”

“Their primary concern would be safety and connectivity. Our drivers use tablets that connect via satellite and cell towers, and we still encounter issues—sometimes losing connection and trip data. That’s a concern for ARSS, especially since there’s no one physically present to troubleshoot in real time (ID: 1008).”

“I could see ARSS working for fixed routes with ambulatory riders only. But all my fixed-route vehicles have wheelchair lifts. What happens the first time someone shows up in a wheelchair? More riders use rollators, scooters, or power chairs than are fully ambulatory (ID: 1006).”

“I can’t imagine a vehicle without a person in it—our drivers often go above and beyond to assist Veterans and help them access higher-level care. I’d strongly advocate for someone to always be present in the vehicle (ID: 1000).”

“If there’s no driver, it could cause anxiety or added stress for any Veteran, regardless of age. Many have experienced trauma, and getting into a vehicle without a person present may raise concerns—like whether they’ll get to the right place or arrive on time. There are just too many unknowns (ID1014).”

“We have more older Veterans than younger. We have younger Veterans who might think, oh, this technology is amazing. However, most of our Veterans who require assistance with transportation are older, and I believe many of them wouldn’t be completely comfortable with a Level 4–5 ARSS because they have a lot of old-school thinking. Most prefer paper surveys over computer surveys, many don’t have access to email, and they don’t use My HealtheVet secure messaging. So even if the technology is great, they’re not utilizing it. Our larger Veteran population that uses transportation wouldn’t be on board with a Level 4–5 ARSS (ID: 1014).”

“There’s probably a link the Vet has to click to approve the ride—some kind of manifest system. But not everyone is tech savvy, and many Vets here are homeless, so you’re assuming they even have a phone (ID1010).”

3.2.6. Communication

“The transportation program has done a fantastic job at the local level of educating Veterans, providers, and administrative staff that transportation services are available. Often, the issue isn’t that Veterans don’t know they can get a ride—it’s that they don’t know who to contact to schedule it. Almost 99% want to speak to someone on the phone. So, it’s more about making sure they’re connected to the right person to help identify what benefits they’re eligible for and ensure they get to their appointments (ID: 1002).”

“We try to get the guidance out to Veterans first, so they understand the criteria to qualify. Once they know, we share updates on Facebook, post them on websites, and provide flyers and brochures so they’re aware of the services (ID: 1004).”

“We don’t have many direct conversations with Veterans. Sometimes they find our number, but everything we do is behind-the-scenes support. Realistically, our name isn’t out there. When Veterans call, it can feel like a carousel—being bounced around from one place to another—which is frustrating, especially since our department doesn’t have the tools to verify their eligibility (ID: 1010).”

“One of our current strengths is communication. Logistically, we coordinate and collaborate across different sections to meet demand, no matter what it is. There’s strong communication with other sites, even outside our region, to ensure we take care of our patients (ID: 1004).”

“The biggest barrier is when the inpatient team doesn’t notify the social worker in time about a Veteran’s discharge. We may get a last-minute request for a trip that could take up to six hours. Our catchment area spans 14,000 square miles—50 counties across NFLSGA—so if we don’t get timely notice, it may be too late in the day to arrange same-day transportation, causing delays (ID: 1014).”

3.2.7. Suggestions for Improvement

“It would be really helpful to have the VTS program at all facilities. It’s available to all Veterans—regardless of service connection—which makes things more streamlined. There’s one place to go for rides, and if demand exceeds capacity, it becomes immediately clear (ID: 1000).”

“From a transportation standpoint, I think it would help to have a one-stop shop. Even though communication is good, it could be better if we were all in one area. There’s a lot of redundancy we could reduce to optimize care and services. Also, with VA drivers, it’s more cost-effective to hire and retain our own staff to meet Veterans’ needs, rather than paying vendors significantly more under contract (ID: 1004).”

“We can do a better job communicating eligibility criteria for VA programs, especially transportation. It would help if public affairs shared clearer messages—like letting veterans know they might qualify for travel reimbursement or ride-share services. Most issues come down to a lack of communication, and we could improve how we educate veterans about their options (ID: 1014).”

“There are too many phone calls, emails, and Teams messages—it wastes time. If everyone were in the same space, we could just ask quick questions and get answers faster than making multiple phone calls or teams messages (ID: 1010).”

“We need broader communication with alternate stakeholders—like staff services or third-party providers. If we’re short a driver, it would help to share a manifest and points of contact so they can step in when needed (ID: 1012).”

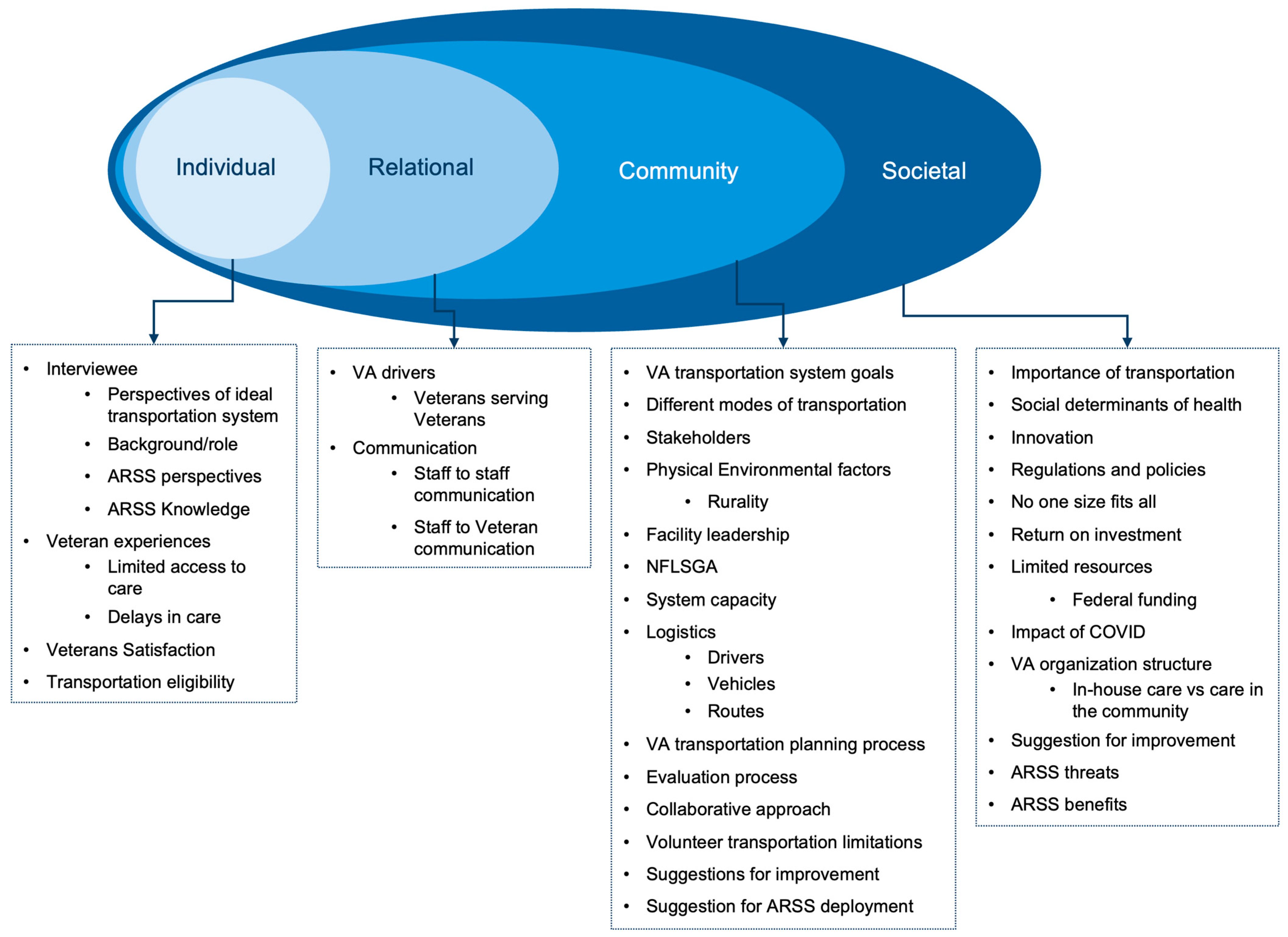

3.3. Findings Related to the Socioecological Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Limitations, Strengths, and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. About the department: Veterans Health Care. 2025. Available online: https://department.va.gov/about/#:~:text=VA's%20Veterans%20Health%20Administration%20is,million%20enrolled%20Veterans%20each%20year (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans Health Administration: About VHA. 2025. Available online: https://www.va.gov/health/aboutvha.asp (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Highly Rural Transportation Grants [Fact Sheet]. 2022. Available online: https://www.va.gov/HEALTHBENEFITS/resources/publications/IB10-761_VA_HRTG_factsheet.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans Transportation Service (VTS). 2019. Available online: https://www.va.gov/healthbenefits/vtp/veterans_transportation_service.asp (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Brownley, J.; Welch, P.; Stabenow, D. Brownley, Welch, and Stabenow Introduce Legislation to Increase Travel Reimbursement for Veterans [Press Release]. 2023. Available online: https://juliabrownley.house.gov/brownley-welch-and-stabenow-introduce-legislation-to-increase-travel-reimbursement-for-veterans/ (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Burkhardt, J.E.; Rubino, J.M.; Yum, J. Improving Mobility for Veterans. Transportation Research Board, 2011. Available online: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/14507 (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Hussey, P.S.; Ringel, J.S.; Ahluwalia, S.; Price, R.A.; Buttorff, C.; Concannon, T.W.; Lovejoy, S.L.; Martsolf, G.R.; Rudin, R.S.; Schultz, D.; et al. Resources and capabilities of the Department of Veterans Affairs to provide timely and accessible care to veterans. Rand Health Q. 2016, 5, 14. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5158229/ (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- SAE. Taxonomy and Definitions for Terms Related to Driving Automation Systems for on-Road Motor Vehicles. 2018. Available online: https://www.sae.org/standards/content/j3016_201806/ (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Shen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, J. Integrating shared autonomous vehicle in public transportation system: A supply-side simulation of the first-mile service in Singapore. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, 113, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmore, A.; Samaras, C.; Hendrickson, C.T.; Matthews, H.S.; Wong-Parodi, G. Integrating public transportation and shared autonomous mobility for equitable transit coverage: A cost-efficiency analysis. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2022, 14, 100571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwangbo, S.W.; Stetten, N.E.; Wandenkolk, I.C.; Li, Y.; Classen, S. Lived experiences of people with and without disabilities across the lifespan on autonomous shuttles. Future Transp. 2024, 4, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Classen, S.; Wandenkolk, I.C.; Mason, J.; Stetten, N.; Hwangbo, S.W.; LeBeau, K. Promoting veteran-centric transportation options through exposure to autonomous shuttles. Safety 2023, 9, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Doerzaph, Z. Road user attitudes toward automated shuttle operation: Pre and post-deployment surveys. Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. Annu. Meet. 2022, 66, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benyahya, M.; Kechagia, S.; Collen, A.; Nijdam, N.A. The interface of privacy and data security in automated city shuttles: The GDPR analysis. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisdell, E.J.; Merriam, S.B.; Stuckey-Peyrot, H.L. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation; Lohn Wiley & Sons: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kahlke, R.M. Generic qualitative approaches: Pitfalls and benefits of methodological mixology. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2014, 13, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portney, L.G.; Watkins, M.P. Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Practice; Pearson/Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, L.A. Snowball sampling. Ann. Math. Stat. 1961, 32, 148–170. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2237615 (accessed on 28 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- MacDougall, C.; Fudge, E. Planning and recruiting the sample for focus groups and in-depth interviews. Qual. Health Res. 2001, 11, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwall, A.; Jewkes, R. What is participatory research? Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 1667–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archibald, M.M.; Ambagtsheer, R.C.; Casey, M.G.; Lawless, M. Using zoom videoconferencing for qualitative data collection: Perceptions and experiences of researchers and participants. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2019, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurl, E. SWOT analysis: A theoretical review. J. Int. Soc. Res. 2017, 10, 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Microsoft. Security and Compliance for Microsoft Teams. 2025. Available online: https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoftteams/security-compliance-overview (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Thunberg, S.; Arnell, L. Pioneering the use of technologies in qualitative research–A research review of the use of digital interviews. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2022, 25, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.R. Kielhofner’s Research in Occupational Therapy: Methods of Inquiry for Enhancing Practice; F.A. Davis: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Parekh, T.; Kumar, B.V.; Maheswar, R.; Sivakumar, P.; Surendiran, B.; Aileni, R.M. Intelligent transportation system in smart city: A SWOT analysis. In Challenges and Solutions for Sustainable Smart City Development; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2023. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software, Version 12; Computer Software; QSR International Pty Ltd.: Doncaster, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondracki, N.L.; Wellman, N.S.; Amundson, D.R. Content analysis: Review of methods and their applications in nutrition education. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2002, 34, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.M.; Field, P.A. Nursing research: The Application of Qualitative Approaches; Nelson Thornes: Cheltenham, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Krefting, L. Rigor in qualitative research: The assessment of trustworthiness. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 1991, 45, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knafl, K.A.; Breitmaye, B.J. Triangulation in qualitative research: Issues of conceptual clarity and purpose. In Qualitative Nursing Research: A Contemporary Dialogue; Morse, J.M., Ed.; Aspen: Rockville, MD, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Buzza, C.; Ono, S.S.; Turvey, C.; Wittrock, S.; Noble, M.; Reddy, G.; Kaboli, P.J.; Reisinger, H.S. Distance is relative: Unpacking a principal barrier in rural healthcare. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2011, 26, 648–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, S.T.; Gerber, B.S.; Sharp, L.K. Traveling towards disease: Transportation barriers to health care access. J. Community Health 2013, 38, 976–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, D.L.; Bean-Mayberry, B.; Riopelle, D.; Yano, E.M. Access to care for women veterans: Delayed healthcare and unmet need. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2011, 26, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zullig, L.L.; Jackson, G.L.; Provenzale, D.; Griffin, J.M.; Phelan, S.; Van Ryn, M. Transportation—A vehicle or roadblock to cancer care for VA patients with colorectal cancer? Clin. Color. Cancer 2012, 11, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Office of Rural Health: Rural Veterans. 2024. Available online: https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/aboutus/ruralvets.asp (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Zhang, W.; Guhathakurta, S.; Fang, J.; Zhang, G. The performance and benefits of a shared autonomous vehicles based dynamic ridesharing system: An agent-based simulation approach. In Proceedings of the Transportation Research Board 94th Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 11–15 January 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schlüter, J.; Bossert, A.; Rössy, P.; Kersting, M. Impact assessment of autonomous demand responsive transport as a link between urban and rural areas. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2021, 39, 100613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prioleau, D.; Dames, P.; Alikhademi, K.; Gilbert, J.E. Autonomous vehicles in rural communities: Is it feasible? IEEE Technol. Soc. Mag. 2021, 40, 28–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohiuddin, H. Planning for the first and last mile: A review of practices at selected transit agencies in the United States. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, C.; Johnson-Kaiser, T.; Ahmad, O. Automated Vehicles in Rural America: What’s the Holdup? Transp. Res. Board 2023, 347, 8–12. Available online: https://www.trb.org/Publications/Blurbs/183152.aspx (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Bezyak, J.L.; Sabella, S.A.; Gattis, R.H. Public transportation: An investigation of barriers for people with disabilities. J. Disabil. Policy Stud. 2017, 28, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbus, S. Final Report for the Smart Columbis Demonstration Program. 2021. Available online: https://d2rfd3nxvhnf29.cloudfront.net/2021-06/SCC-J-Program-Final%20Report-Final-V2_0.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Bennett, R.; Vijaygopal, R.; Kottasz, R. Attitudes towards autonomous vehicles among people with physical disabilities. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2019, 127, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicianno, B.E.; Sivakanthan, S.; Sundaram, S.A.; Satpute, S.; Kulich, H.; Powers, E.; Deepak, N.; Russell, R.; Cooper, R.; Cooper, R.A. Systematic review: Automated vehicles and services for people with disabilities. Neurosci. Lett. 2021, 761, 136103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianin, A.; Ravazzoli, E.; Hauger, G. Implications of autonomous vehicles for accessibility and transport equity: A framework based on literature. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golchin, M.; Grandhi, A.; Gore, N.; Pulugurtha, S.S.; Ghasemi, A. UNC Charlotte Autonomous Shuttle Pilot Study: An Assessment of Operational Performance, Reliability, and Challenges. Machines 2024, 12, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacace, S.; Smith, E.; Desmarais, S.; Alders, E. Locale matters: Regional needs of US military service members and veterans. Mil. Behav. Health 2022, 10, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvanta, C.; Nelson, D.E.; Harner, R.N. Public Health Communication: Critical Tools and Strategies; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Veterans Affairs. Asset and Infrastructure Review Commission. 2022. Available online: https://www.va.gov/AIRCOMMISSIONREPORT/docs/VA-Report-to-AIR-Commission-Volume-I.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2025).

| Themes/Subthemes | Operational Definitions of Themes and Subthemes |

|---|---|

| Complex system | The VA transportation system consists of multiple interconnected components, including the various modes of transportation, regulatory frameworks, diverse stakeholders, processes of change, and access to care. Each element contributes to the system’s complexity and functionality. |

| Different modes of transportation | Includes special mode transport for wheelchair- and stretcher-bound patients, Uber/Lyft and volunteer services for ambulatory veterans, and beneficiary travel for travel reimbursement. MAS outsources to vendors for trips to veterans that require a special mode of transportation. Each mode of transportation addresses different needs. |

| Regulations and policy | The regulatory structure is complex, involving multiple layers of rules and guidelines that influence funding, programs, and standard operating procedures for day-to-day operations. This complexity often leads to challenges in service provision, requiring flexibility and adaptation by transportation services. |

| Diverse stakeholders | The system involves veterans, caregivers, healthcare personnel, the ORH, the Veterans Experience Office, and community partners, such as the Disabled American Veterans (DAV). Stakeholders have a unique role in determining transportation needs, organizing services, managing complaints and working toward service improvements. |

| Process of change | The VA is integrating new technologies and piloting new services to improve accessibility. Challenges include technology reliance, coordination issues, and engagement difficulties. Efforts focus on identifying transportation deserts, expanding resources, and overcoming barriers to enhance service provision. |

| Access to care | Reliable transportation impacts veterans’ health outcomes by providing access to primary, specialty, and mental health services. High outsourcing costs emphasize the need to bring care back to VA facilities. Strict eligibility criteria and limited service availability pose significant barriers, especially in rural areas. |

| Transportation strengths | Strengths include the NFLSGA unique ability to provide a wide range of flexible and adaptive transportation services, strong collaboration between various transportation departments and external contractors, and personalized, high-quality services facilitated by trained and dedicated drivers, many of whom are veterans themselves. |

| NFLSGA-unique | NFLSGA is unique due to its geographic reach and the range of services it offers. It is flexible and adaptable and transports those who may not qualify under beneficiary travel criteria. The integration of services under one umbrella allows NFLSGA to cater to a wide array of needs, making it distinct from other facilities. |

| Collaborative approach | Collaborative efforts with various stakeholders, such as social workers, nurses, and external contractors. This integrated approach ensures coordinated care and addresses the social determinants of health by working closely with all stakeholders involved in veterans’ healthcare. |

| Better customer service product | The VA transportation services are tailored to veterans’ needs, providing door-to-door service, better tracking, and higher safety standards. This personalized approach enhances veterans’ overall experience. |

| Drivers working for the VA | The employment of veterans as drivers, who share a unique bond and understanding with their passengers. This veteran-to-veteran interaction provides comfort and encouragement to veterans. The high training standards and commitment to service further enhance the reliability and quality of the transportation provided. |

| Transportation weaknesses | Limited resources, such as insufficient funding, manpower, and vehicles. Reliance on volunteer transportation presents challenges, including inconsistency, and restrictions on the types of patients that can be transported. Strict eligibility criteria further complicate access to transportation services. |

| Limited resources | Insufficient manpower, vehicles, and funding to meet the transportation demands of veterans. This impacts the ability to provide timely and effective transportation services, as highlighted by the constraints of staffing and vehicle availability due to budget cuts and funding limitations. |

| Volunteer transportation limitations | Challenges in relying on volunteers for transportation services, including inconsistency of volunteer availability, lack of medical training, and restrictions on the types of patients they can transport. |

| Eligibility | Strict criteria that veterans must meet to qualify for certain transportation services. The criteria often exclude veterans who do not meet specific administrative or clinical requirements, thereby limiting their access to transportation services and impacting their access to healthcare. |

| ARSS opportunities | Potential advantages and strategic recommendations for deploying ARSSs. Perceived benefits include increased efficiency, resource reallocation, and improved accessibility for underserved populations. Suggestions for deployment include its integration in urban areas and hospital campuses. |

| Perceived benefits | Perceived benefits include the potential for increased efficiency and resource allocation within transportation services. By automating aspects of transportation, human resources can potentially be reallocated to other tasks. ARSSs may improve accessibility for veterans by providing consistent and reliable transportation options. |

| Suggestions for ARSS deployment | Implementing fixed routes, focusing on short trips, and providing transportation services in small communities. Serving able and ambulatory veterans and deployment in urban areas as a last leg of trip. Incorporating ARSS in hospital campuses and parking lots may benefit both veterans and employees. |

| ARSS threats | The ARSS threats are the potential challenges and barriers that could impede the effective implementation and operation of ARSS. These threats encompass logistical, accessibility, and adoption issues. |

| ARSS logistics | Limited application for rural veterans due to varied trips and geographical components. Funding limitations, connectivity issues, road conditions, operational constraints and the suitability of vehicles for different terrains and weather conditions, and limited reach due to reliance on fixed routes. |

| Serving PWDs | Serving PWDs in the context of ARSS involves ensuring that these services are accessible and accommodating to individuals with mobility challenges. This includes having personnel available to assist, which may be challenging with ARSSs that lack onboard staff to help with wheelchairs, scooters, or other assistive devices. |

| ARSS adoption | Factors influencing adoption include trust in the technology, comfort levels with driverless vehicles, and the perceived reliability of these services. This is particularly challenging for older veterans, those living in rural areas, homeless veterans and those with no access to technology or limited technological proficiency. |

| Communication | Encompasses the methods and effectiveness of information exchange between staff members and between staff and veterans. It involves ensuring that all parties are informed about transportation options, eligibility criteria, scheduling processes, and service availability. |

| Staff to staff communication | Effective communication is important for coordinating transportation for veterans. Challenges include timely communication between inpatient teams and social workers, which can delay discharges. Regular and structured communication among departments is needed to ensure smooth operations and timely transportation services. |

| Veteran and staff communication | Clear communication between veterans and VA staff ensures that veterans are aware of the transportation services available to them and understand the eligibility criteria. This involves disseminating information through various channels and ensuring veterans are connected to the right personnel for scheduling transportation. |

| Suggestions for improvement | Streamline services by integrating departments under a unified system. The focus is on reducing redundancy, improving coordination, and ensuring that veterans have better access to transportation options through clear eligibility criteria and efficient scheduling processes. |

| Streamline services | Consolidate departments and services under a unified system to reduce redundancy and improve efficiency. By centralizing services, the VA can enhance coordination, reduce operational delays, and better manage resources. This also includes hiring more drivers and transportation staff and reducing reliance on external vendors. |

| Communication strategies | Enhancing communication strategies includes improving internal communication within the VA and external communication with veterans. Developing a centralized communication hub and utilizing public affairs to disseminate information about transportation eligibility and services can improve awareness and access. |

| SWOT Framework | Theme | Take-Home Messages |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths (internal factors) |

| The VA transportation system is multifaceted, involving a variety of transportation options across diverse stakeholders, which reflects the richness and adaptability of the system. Strengths include the unique aspects of the NFLSGA system due to its geographical size and transportation flexibility; a collaborative care model; personalized customer service; and the employment of veterans as drivers, which enhances satisfaction and service quality. Effective communication among staff and with veterans is a system strength that supports coordination and user satisfaction. Although forward-looking, many of the proposed improvements (e.g., hiring more drivers, centralizing departments, enhancing communication) depend on internal restructuring and policy change, aligning them with internal strengths that can be developed. |

| Weaknesses (internal factors) |

| Certain aspects, like regulatory burdens and fragmented access, expose internal inefficiencies that complicate service delivery. Weaknesses include funding constraints, a shortage of staff and drivers, inconsistency and reliability issues with volunteer drivers, and restrictive eligibility criteria. Addressing staffing shortages and budget constraints is essential for improving service delivery. Communication is a double-edged theme, which also includes organizational inefficiencies and access barriers (e.g., veterans not knowing the correct point of contact, last-minute discharge notices, limited direct outreach, and redundant communication workflows). |

| Opportunities (external factors) |

| ARSS may expand the pool of transportation employees, provide reliable access points in urban areas, and assist rural veterans by standardizing and easing final leg journeys. They may also alleviate staffing constraints and offer a scalable solution for short trips. |

| Threats (external factors) |

| Threats include logistical challenges in rural areas, limited connectivity, safety concerns, difficulties in serving veterans with disabilities, and adoption barriers due to trust and technology acceptance issues. Threats need to be addressed to support ARSS implementation. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wandenkolk, I.; Winter, S.; Stetten, N.; Classen, S. Department of Veterans Affairs’ Transportation System: Stakeholder Perspectives on the Current and Future System, Including Electric Autonomous Ride-Sharing Services. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 293. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16060293

Wandenkolk I, Winter S, Stetten N, Classen S. Department of Veterans Affairs’ Transportation System: Stakeholder Perspectives on the Current and Future System, Including Electric Autonomous Ride-Sharing Services. World Electric Vehicle Journal. 2025; 16(6):293. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16060293

Chicago/Turabian StyleWandenkolk, Isabelle, Sandra Winter, Nichole Stetten, and Sherrilene Classen. 2025. "Department of Veterans Affairs’ Transportation System: Stakeholder Perspectives on the Current and Future System, Including Electric Autonomous Ride-Sharing Services" World Electric Vehicle Journal 16, no. 6: 293. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16060293

APA StyleWandenkolk, I., Winter, S., Stetten, N., & Classen, S. (2025). Department of Veterans Affairs’ Transportation System: Stakeholder Perspectives on the Current and Future System, Including Electric Autonomous Ride-Sharing Services. World Electric Vehicle Journal, 16(6), 293. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16060293