Sustainable Port Horizontal Transportation: Environmental and Economic Optimization of Mobile Charging Stations Through Carbon-Efficient Recharging

Abstract

1. Introduction

- i.

- A unified carbon-efficiency framework: We develop a novel bi-objective framework for directly comparing Mobile Charging Stations (MCSs), Fixed Charging Stations (FCSs), and Battery Swapping Stations (BSWSs). Unlike studies that evaluate these technologies in isolation, our model integrates both operational electricity use and embedded battery carbon emissions under a carbon-efficiency paradigm.

- ii.

- Operational realism with real-world validation: The model incorporates critical operational factors often overlooked in strategic planning, such as vehicle detours, non-operational mileage, and the reuse of crane idle time for charging. It is calibrated and validated using real-world data from Shenzhen Mawan Port, including vehicle routes, energy consumption, and task schedules.

- iii.

- Identification of a critical operational threshold: Our analysis reveals a key nonlinear threshold (0.5–0.75) in the reuse ratio, defining a shift from carbon-conserving to profit-maximizing regimes. This finding provides actionable insights for port operators to balance environmental and economic objectives.

- iv.

- Practical decision support for infrastructure planning: The framework generates deployable configurations and offers clear guidance for port planners to select among MCSs, FCSs, and BSWSs based on specific priorities, including carbon-profit trade-offs, land constraints, and achievable reuse levels.

2. Materials and Methods

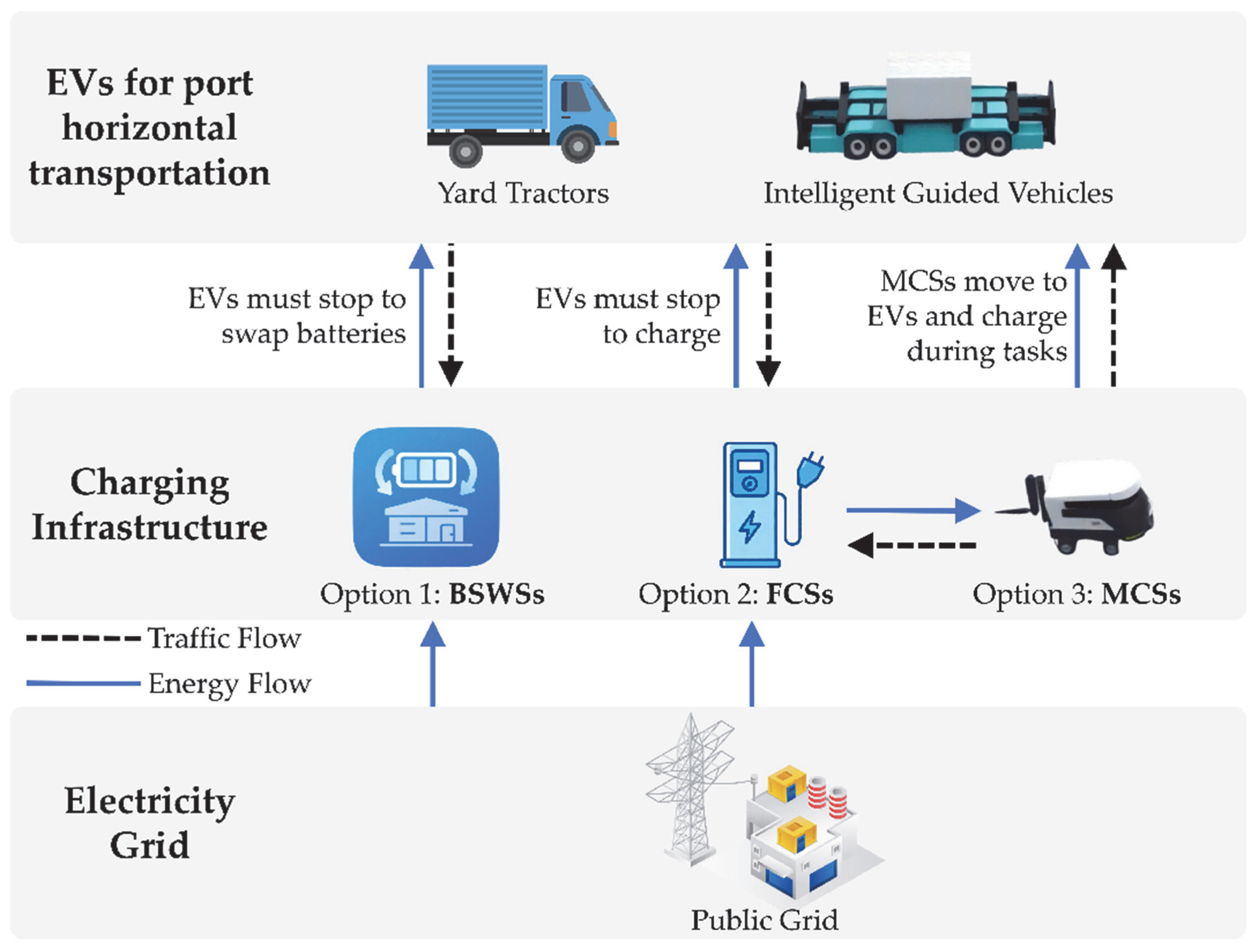

2.1. MCSs Solution

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Carbon-Efficient-Driven Multi-Objective Optimization Model

2.3.1. Carbon-Efficient Metrics

- i.

- E1: Direct carbon emissions refer to physical emissions within a defined boundary, such as tailpipe emissions during vehicle operation or grid-based emissions during charging. For electric vehicles, this primarily involves emissions from electricity production during charging. Activity-Based Accounting is used to quantify CO2-equivalent emissions throughout the entire horizontal transportation process.

- ii.

- E2: Embedded carbon emissions include greenhouse gas emissions from battery production and recycling, covering indirect emissions from raw material extraction, manufacturing, transportation, and recycling processes.

2.3.2. Definition of Decision Variables

- i.

- Bev ∈ (0, 300]: Battery capacity for the operating EV fleet (e.g., 210 kWh for battery-swapped EVs, 280 kWh for charging EVs [16]). The battery capacity must meet the EV range requirements to ensure they can complete tasks between charging sessions. Increasing the battery capacity significantly raises vehicle acquisition costs, necessitating a balance between range requirements and cost considerations.

- ii.

- Pmcs ∈ [100, 600]: Charging power of the MCSs, in kilowatts (kW). Higher charging power can reduce charging time, improving equipment utilization and lowering operational costs. However, the purchase and operational expenses of high-power charging equipment are also higher.

- iii.

- Bmcs ∈ (0, 1500]: The battery capacity of one MCS (in kWh). The battery capacity must be sufficient to meet the operational range requirements of MCSs, ensuring they can charge EVs during their operation without needing to return to the FCSs for recharging.

- i.

- Nmcs ∈ R+: The quantity of MCSs deployed, which must be determined based on the port’s operational and charging demands. The quantity of MCSs should strike a balance among acquisition, operating, and land opportunity costs, while ensuring sufficient scheduling flexibility to adapt to dynamic changes in port operations.

- ii.

- Nev ∈ R+: The quantity of operating EVs. This refers to the total quantity of electric vehicles actively operating at the port. The quantity of EVs influences charging service demand and should be optimized to ensure sufficient charging capacity while minimizing idle time and improving operational efficiency across both EVs and MCSs.

2.3.3. Objective Function Framework

- i.

- Environmental Objective Function (Minimizing Total Life-Cycle Carbon Emissions)

- ii.

- Economic Objective Function to maximize Net Present Value (NPV)

- i.

- As the quantity of MCSs (Nmcs) increases, the acquisition cost (Ccap) rises linearly due to the higher quantity of units, while operational costs (Cop) may decrease. This is because more MCSs improve scheduling efficiency, reducing the frequency of individual MCS usage and maintenance costs.

- ii.

- As battery capacity (Bev) decreases, Ccap decreases due to lower battery capacity and thus lower initial costs. However, Cop may increase due to more frequent charging, leading to higher energy and maintenance costs.

- iii.

- As charging power (Pmcs) increases, Ccap may rise due to the higher expense of high-power charging equipment. However, Cop may decrease because the reduced charging time enhances equipment utilization.

2.3.4. Normalization of Output Metrics

- i.

- Normalized NPV: This is computed by dividing the NPV by the total TEU throughput, yielding a normalized value that reflects the economic efficiency per unit of cargo handled.

- ii.

- Normalized Carbon Emissions: Similarly, carbon emissions are normalized by dividing total emissions by the total TEU throughput, enabling a fair comparison of carbon efficiency across different system configurations.

2.3.5. Constraints Decomposition

- i.

- Satisfying Charging Demand

- ii.

- Satisfying Energy Storage Safety Limits

- iii.

- Satisfying Charging Pile and Battery Capacity Limits

- i.

- For the MCSs solution

- ii.

- For the FCSs charging pile:

- iii.

- For the BSWSs Charging Battery:

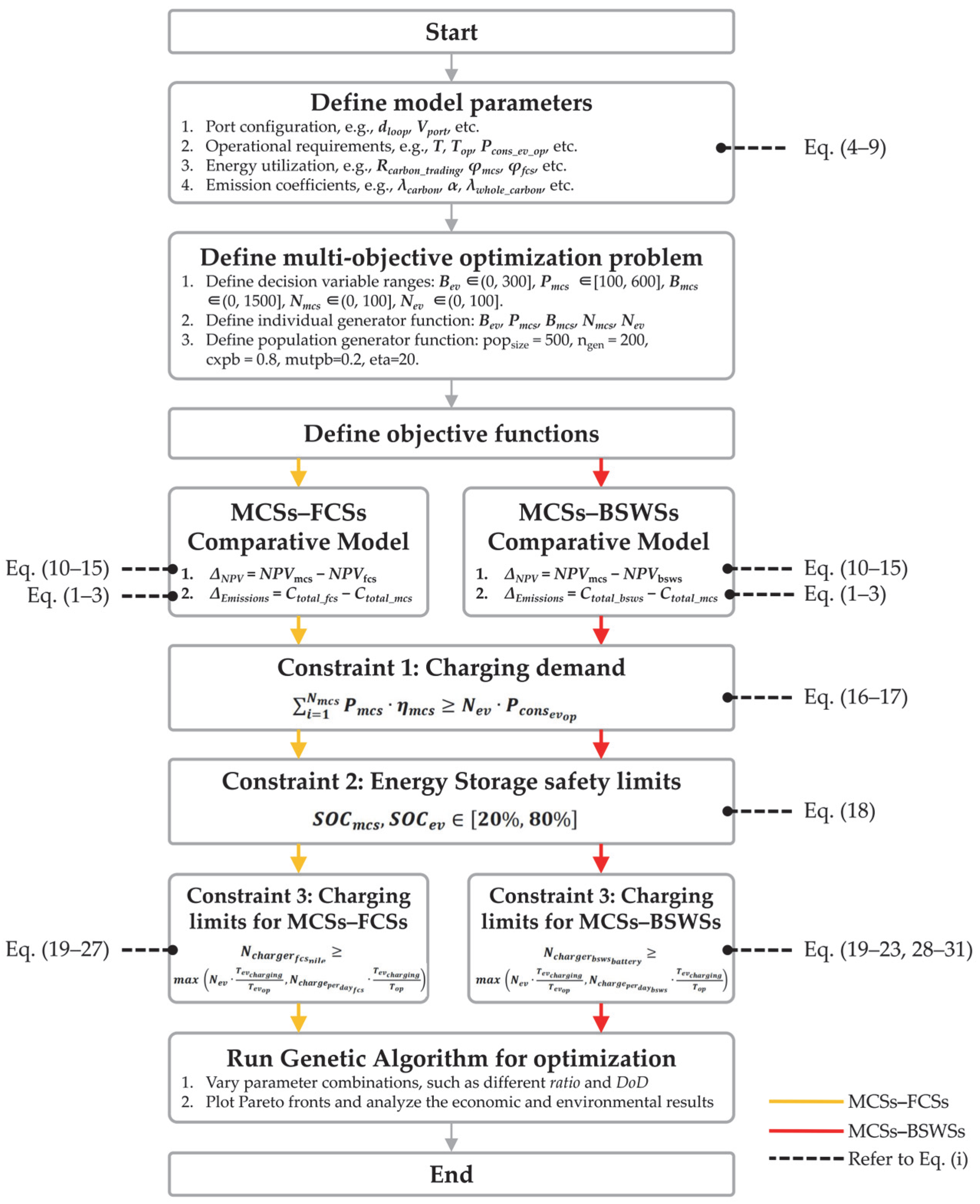

2.4. Model Solution Process

- i.

- MCSs–FCSs Comparative Model: Evaluates MCSs against FCSs by calculating the relative Net Present Value (ΔNPV = NPVmcs − NPVfcs) and carbon emission differentials (ΔEmissions = Ctotal_fcs − Ctotal_mcs);

- ii.

- MCSs–BSWSs Comparative Model: Assesses MCSs’ performance relative to BSWSs through analogous relative metrics (ΔNPV = NPVmcs − NPVbsws; ΔEmissions = Ctotal_bsws − Ctotal_mcs).

- i.

- For MCSs–FCSs comparisons: Vehicle dwell time patterns, fixed infrastructure CAPEX, and grid emission intensity;

- ii.

- For MCSs–BSWSs comparisons: Battery inventory costs, swapping time thresholds, and lithium-ion degradation factors.

- i.

- Scenario Encoding: Generates population matrices representing charging station deployment schemes, with distinct gene structures for FCSs and BSWSs comparison scenarios;

- ii.

- Fitness Evaluation: Calculates ΔNPV using discounted cash flow analysis and ΔEmissions through life-cycle assessment (LCA) coefficients;

- iii.

- Constraint Handling: Applies dynamic penalty functions to maintain feasible solutions across both models’ operational constraints.

3. Results

3.1. For the MCSs–FCSs Model

3.2. For the MCSs–BSWSs Model

3.3. Normalized Output Metrics

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings and Mechanism Explanation

4.2. Sensitivity Analysis

4.2.1. Small vs. Large Changes

4.2.2. Nonlinear Effect

4.2.3. Depth-of-Discharge (DoD) Sensitivity

4.3. Limitations and Social-Governance Aspects

4.3.1. Social (S) Factors

4.3.2. Governance (G) Factors

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Williamsson, J.; Costa, N.; Santén, V.; Rogerson, S. Barriers and Drivers to the Implementation of Onshore Power Supply—A Literature Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvvala, J.; Kumar, K.S. Implementation of EFC Charging Station by Multiport Converter with Integration of RES. Energies 2023, 16, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivari, E.; Gurrì, S.; Caballini, C.; Carotta, T.; Chiara, B.D. Ports Go Green: A Cost-Energy Analysis Applied to a Case Study on Evaluating the Electrification of Yard Tractors. Open Transp. J. 2024, 18, e26671212308027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoun, A.; Adda, M.; Ilinca, A.; Ghandour, M.; Ibrahim, H. Dynamic Charging Optimization Algorithm for Electric Vehicles to Mitigate Grid Power Peaks. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ruan, N.; Ma, J. Organizational Innovation of Chinese Universities of Applied Sciences in Less-Developed Regional Innovation Systems. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo-Díaz, C.; Linfati, R.; Escobar, J.W. Mathematical Model for the Electric Vehicle Routing Problem Considering the State of Charge of the Batteries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Analysis of Battery Swapping Technology for Electric Vehicles—Using NIO’s Battery Swapping Technology as an Example. SHS Web Conf. 2022, 144, 02015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honma, Y.; Toriumi, S. Mathematical Analysis of Electric Vehicle Movement with Respect to Multiple Charging Stops. J. Energy Eng. 2017, 143, F4016007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Chen, L.; Fang, S.; Liu, Y. The Routing Problem for Electric Truck with Partial Nonlinear Charging and Battery Swapping. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadati, M.E.H.; Akbari, V.; Çatay, B. Electric Vehicle Routing Problem with Flexible Deliveries. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 60, 4268–4294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarar, M.O.; Hassan, N.U.; Naqvi, I.H. On the Economic Feasibility of Battery Swapping Model for Rapid Transport Electrification. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Europe (ISGT Europe), Espoo, Finland, 18–21 October 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Singh, R.; Arora, P.; Mahapatra, D. Assessment of Total Cost of Ownership for Electric Two-Wheelers with Point Charging and Battery Swapping in the Indian Scenario. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference and Utility Exhibition on Energy, Environment and Climate Change (ICUE), Pattaya, Thailand, 26–28 October 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Yao, S.; Zeng, X.; Yang, P.; Zhao, Z.; Lai, C.S.; Lai, L.L. Operation Strategy for Electric Vehicle Battery Swap Station Cluster Participating in Frequency Regulation Service. Processes 2021, 9, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhang, C. Configuration and Operation Combined Optimization for EV Battery Swapping Station Considering PV Consumption Bundling. Prot. Control. Mod. Power Syst. 2017, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, H.-Y.; Rong, Y.; Shen, Z.-J.M. Infrastructure Planning for Electric Vehicles with Battery Swapping. Manag. Sci. 2013, 59, 1557–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Han, W.; Tian, H.; Huang, J. Empirical Analysis of the Benefits of Intelligent Mobile Recharging Solution for Port Horizontal Transportation Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 8th Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration (EI2), Shenyang, China, 29 November–2 December 2024; pp. 1646–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Hua, G. A Location-Sizing Model for Electric Vehicle Charging Station Deployment Based on Queuing Theory. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Logistics, Informatics and Service Sciences (LISS), Barcelona, Spain, 27–29 July 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriar, S.; Al-Ali, A.R.; Osman, A.H.; Dhou, S.; Nijim, M. Machine Learning Approaches for EV Charging Behavior: A Review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 168980–168993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Lim, J.; Won, W.; Kim, J.; Ga, S. Design and Optimization of Energy Supplying System for Electric Vehicles by Mobile Charge Stations. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2024, 138, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leijon, J.; Boström, C. Charging Electric Vehicles Today and in the Future. World Electr. Veh. J. 2022, 13, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Răboacă, M.-S.; Băncescu, I.; Preda, V.; Bizon, N. An Optimization Model for the Temporary Locations of Mobile Charging Stations. Mathematics 2020, 8, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Chen, R.; Miao, L.; Yang, P.; Ye, B. Location Optimization of Electric Vehicle Mobile Charging Stations Considering Multi-Period Stochastic User Equilibrium. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, G.; Xu, Y. Optimal Deployment of Charging Stations and Movable Charging Vehicles for Electric Vehicles. J. Syst. Manag. Sci. 2019, 9, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Ye, Z.; Jia, H. A Charging Planning Method for Shared Electric Vehicles with the Collaboration of Mobile and Fixed Facilities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktar, A.K.; Tascikaraoglu, A.; Catalao, J.P.S. Optimal Charging and Discharging Operation of Mobile Charging Stations. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Smart Energy Systems and Technologies (SEST), Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 5–7 September 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.; Choi, D.-H. Optimal Energy Management Framework for Truck-Mounted Mobile Charging Stations Considering Power Distribution System Operating Conditions. Sensors 2021, 21, 2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jozwiak, D.; Pillai, J.R.; Ponnaganti, P.; Bak-Jensen, B.; Jantzen, J. Optimal Charging and Discharging Strategies for Electric Cars in PV-BESS-Based Marina Energy Systems. Electronics 2023, 12, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Li, P. Politics of Urban Energy Transitions: New Energy Vehicle (NEV) Development in Shenzhen, China. Environ. Politics 2019, 29, 524–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahnes, M.; Zhou, L.; Preindl, M. Design of a 22-kW Transformerless EV Charger with V2G Capabilities and Peak 99.5% Efficiency. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Carbon Market Trading Price Rises Steadily [N/OL]. China Energy News. 13 January 2025. Available online: http://paper.people.com.cn/zgnyb/pad/content/202501/13/content_30052542.html (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Llamas-Orozco, J.A.; Meng, F.; Walker, G.S.; Abdul-Manan, A.F.N.; MacLean, H.L.; Daniel Posen, I.; McKechnie, J. Estimating the Environmental Impacts of Global Lithium-Ion Battery Supply Chain: A Temporal, Geographical, and Technological Perspective. PNAS Nexus 2023, 2, pgad361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, T.; Alharbi, T. Exploring Lithium-Ion Battery Degradation: A Concise Review of Critical Factors, Impacts, Data-Driven Degradation Estimation Techniques, and Sustainable Directions for Energy Storage Systems. Batteries 2024, 10, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wietheger, S.; Doerr, B. A Mathematical Runtime Analysis of the Non-Dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm III (NSGA-III). In Proceedings of the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference Companion, Melbourne, Australia, 14–18 July 2024; pp. 63–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, I.; Gandomi, A.H.; Deb, K.; Chen, F.; Nikoo, M.R. Scheduling by NSGA-II: Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Processes 2022, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Description | Unit | Data Source/Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| α | Weighting coefficient for carbon emissions | / | Equal-weight aggregation, α = 1 for simplicity (no separate weighting of direct/embedded emissions) |

| β | Weighting coefficient for maintenance costs differentiated across charging modalities (FCSs, BSWSs, MCSs) | / | Assumed values based on operational complexity: 5% for FCSs, 8% for BSWSs, 6% for MCSs |

| Bev | Battery capacity for the operating EV fleet | kWh | 280 for FCSs and 210 for BSWSs [16] |

| Bmcs | The battery capacity of one MCS | kWh | Decision Variable (0–300) |

| Cbattery | The cost of battery acquisition per kWh | CNY/kWh | 1000 [16] |

| Ccap | Initial acquisition cost (including MCSs, batteries, and charging equipment) | CNY | Calculated, Equation (14), using Nev, Cev, Nmcs, Cmcs, Bev, Bmcs, Cbattery, Ccharger |

| Ccharger | The cost of the charging infrastructure for EVs | CNY | 150,000 [16] |

| Cev | The cost of one EV without battery | CNY | 550,000 (Based on typical market values for EVs in port operations) |

| Cmcs | The cost of one MCS without battery | CNY | 500,000 [16] |

| Cop | The operational costs (including energy costs, maintenance fees, etc.) | CNY | Calculated, Equation (15), using β, Ccap |

| Ctotal_bsws | The total life-cycle carbon emissions of BSWSs solution | kg CO2 | Calculated, Equation (1), using T, E1, α, E2 |

| Ctotal_fcs | The total life-cycle carbon emissions of FCSs solution | kg CO2 | Calculated, Equation (1), using T, E1, α, E2 |

| Ctotal_mcs | The total life-cycle carbon emissions of MCSs solution | kg CO2 | Calculated, Equation (1), using T, E1, α, E2 |

| ΔEmissions | Difference in total carbon emissions between MCS and BSWS/FCS | kg CO2 | Calculated from Ctotal_bsws, Ctotal_fcs, Ctotal_mcs |

| ΔNPV | Relative Net Present Value | CNY | Calculated from NPVbsws, NPVfcs, NPVmcs |

| dday | The total distance traveled by one EV during one operational day | km | Calculated, Equation (12), using Top, Tev_op, Tev_empty, Tev_charging, Nev, Bev, SOCev, Vport, Pcons_ev_op |

| dempty | Round-trip distance to charging station | km | 2 [16] |

| dloop | Average distance for EVs to load/unload one TEU | km | 2 [16] |

| DoD | Depth of Discharge (percentage of battery discharge) | / | Calculated, Equation (18), using SOCmcs, SOCev |

| E1 | Direct carbon emissions | kg CO2 | Calculated, Equation (2), using Top, Nev, Pcons_ev_op, ɛev_op, Pcons_ev_empty, εev_empty, Nmcs, Pcons_mcs_op, εmcs_op, Pcons_mcs_empty, εmcs_empty, λcarbon |

| E2 | Embedded carbon emissions | kg CO2 | Calculated, Equation (3), using Nev, Bev, Nmcs, Bmcs, λwhole_carbon |

| mcs | Proportion of MCSs’ output covering charging demand | / | Calculated, Equation (17), using Tmcs_op, Tmcs_empty, Tmcs_charging |

| fcs | Charging conversion efficiency of FCSs to EVs or MCSs | / | 0.95 [29] |

| mcs | Charging conversion efficiency of MCSs to EVs | / | 0.95 [29] |

| λ1 | Comparative ratio for MCS energy consumption (see Equation (19)) | / | 0.9 (Assumed to reflect a ~10% reduction due to lighter vehicle mass) |

| λcarbon | Grid carbon emission factor | kg CO2/kWh | 0.57 kg CO2/kWh (Chinese regional grid benchmark) |

| λwhole_carbon | Life-cycle carbon intensity of the battery | kg CO2/kWh | 65 (based on industry reports and lifecycle assessments [29]) |

| Ncharger_bsws_battery | The quantity of BSWSs’ charging batteries | / | Calculated, Equation (30), using Nev, Ncharger_per_day_bsws, Bev, SOCev, Pbsws |

| Ncharger_fcs_pile | The quantity of FCSs’ charging piles | / | Calculated, Equations (26) and (27), using Nev, Ncharger_per_day_fcs, Bev, SOCev, Pfcs, Tev_charging, Tev_op, Top |

| Ncharger_mcs_pile | The quantity of MCSs’ charging piles | / | Calculated, Equations (22) and (23), using Nmcs, Ncharger_per_day_mcs, Bmcs, SOCmcs, Pfcs, Tmcs_charging, Tmcs_op, Top |

| Ncharger_per_day_bsws | The daily charging frequency of BSWSs | / | Calculated, Equation (29), using Top, Tcycle_bsws |

| Ncharger_per_day_fcs | The daily charging frequency of FCSs | / | Calculated, Equation (25), using Top, Tcycle_fcs |

| Ncharger_per_day_mcs | The daily charging frequency of MCSs | / | Calculated, Equation (21), using Top, Tcycle_mcs |

| Nev | The quantity of operating EVs | / | Decision Variable (Nev ∈ R+) |

| Nmcs | The quantity of MCSs deployed | / | Decision Variable (Nmcs ∈ R+) |

| NPVbsws | Net Present Value of BSWSs solution | CNY | Calculated, Equation (10), using T, Rop, Cop, r, Ccap |

| NPVfcs | Net Present Value of FCSs solution | CNY | Calculated, Equation (10), using T, Rop, Cop, r, Ccap |

| NPVmcs | Net Present Value of MCSs solution | CNY | Calculated, Equation (10), using T, Rop, Cop, r, Ccap |

| Pbsws | Charging power from BSWSs to EVs | kW | 200 (Estimated industry benchmark) |

| Pcons_ev_empty | Driving energy consumption coefficient of EVs under non-operation | kW | 15 (Estimated industry benchmark) |

| Pcons_ev_op | Driving energy consumption coefficient of EVs under operation | kW | 30 (Estimated industry benchmark) |

| Pcons_ev_op_mcs | Operative driving energy consumption coefficient of EVs (MCSs solution) | kW | Calculated, Equation (19), using Pcons_ev_op, λ1 |

| Pfcs | Charging power supplied by FCSs to EVs or MCSs | kW | 200 (Estimated industry benchmark) |

| Pmcs | Charging power of the MCSs | kW | Decision Variable (100–600) |

| r | Discount rate for NPV calculations | / | 5% (Assumed for financial assessments) |

| ratio | MCS deployment ratio (proportion of charging time during EVs’ waiting for quay and yard cranes) | / | Parameter for sensitivity analysis, tested in the range 0–1 |

| Rcarbon | The carbon emission benefit from carbon trading for port enterprises | CNY | Calculated, Equation (13), using Ctotal_fcs, Ctotal_mcs, Rcarbon_trading |

| Rcarbon_trading | The carbon emission price | CNY/ton | 100 (baseline carbon price assumed for the model; the official closing price on 31 December 2024 was 97.49 CNY/ton [30]) |

| Rop | The operational revenue | CNY | Calculated, Equation (12), using Rteu, Nteu, Rcarbon |

| Rteu | The revenue per twenty-foot equivalent unit | CNY/TEU | 20 (Estimated industry benchmark) |

| SOCev | State of charge of EVs | / | Parameter for constraints in Equation (18) |

| SOCmcs | State of charge of MCSs | / | Parameter for constraints in Equation (18) |

| T | Lifecycle duration (consistent with EVs’ service life and battery lifespan) | year | 8 (Typical EV/battery service life) |

| Tcycle_bsws | The interval between single charges of BSWSs | hour | Calculated, Equation (28), using Bev, SOCev, Pcons_ev_op |

| Tcycle_fcs | The interval between single charges of FCSs | hour | Calculated, Equation (24), using Bev, SOCev, Pcons_ev_op |

| Tcycle_mcs | The interval between single charges of MCSs | hour | Calculated, Equation (20), using Bev, SOCev, Pcons_ev_op_mcs |

| Tev_charging | Charging interval between successive EVs charging sessions | hour | mcs, Bev, SOCev, Pfcs, Pmcs |

| Tev_empty | Non-operational interval between successive EVs charging sessions | hour | Calculated, Equation (5), using dempty, Vport |

| Tev_op | Operational interval between successive EVs charging sessions | hour | Calculated, Equation (4), using Bev, SOCev, Pcons_ev_op |

| Tmcs_charging | Charging interval between successive MCSs charging sessions | hour | fcs, Bmcs, SOCmcs, Pfcs |

| Tmcs_empty | Non-operational interval between successive MCSs charging sessions | hour | Calculated, Equation (8), using dempty, Vport |

| Tmcs_op | Operational interval between successive MCSs charging sessions | hour | mcs, Bmcs, SOCmcs, Pmcs |

| Top | Port operation duration per day | hour | 12 (Estimated industry benchmark) |

| Vport | Average vehicle speed in port | km/h | 15 [16] |

| System Comparison | ratio | Max Normalized ΔNPV (CNY/TEU) | Corresponding ΔEmissions (kg/TEU) | Max Normalized ΔEmissions (kg/TEU) | Corresponding ΔNPV (CNY/TEU) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCSs vs. FCSs | 0 | 5.4440 | −0.0884 | 1.3625 | 0.9630 |

| 0.25 | 5.4456 | −0.0870 | 1.3783 | 0.8226 | |

| 0.5 | 5.7380 | −0.0858 | 1.3699 | 2.6790 | |

| 0.75 | 6.0083 | −0.0755 | 1.3625 | 4.5226 | |

| 1 | 6.4592 | 1.3416 | 1.3833 | 6.1218 | |

| MCSs vs. BSWSs | 0 | 0.9889 | 3.6003 | 10.2675 | −26.2053 |

| 0.25 | 2.3152 | 3.6221 | 10.2621 | −17.8831 | |

| 0.5 | 3.7149 | 3.6155 | 10.2765 | −9.7459 | |

| 0.75 | 5.1160 | 3.6081 | 10.2557 | −1.2597 | |

| 1 | 7.0639 | 10.2525 | 10.2718 | 6.9267 |

| Parameter | Sensitivity Level | Normalized ΔNPV (CNY/TEU) | Normalized ΔEmissions (kg/TEU) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ccap (+50%) | Low impact | −0.27% | +0.43% |

| Ccap (−50%) | Low impact | +0.74% | −0.03% |

| Top (+50%) | Medium impact | −6.45% | +3.65% |

| Top (−50%) | Medium impact | +11.52% | −9.49% |

| Rcarbon_trading (+50%) | Medium impact | +6.05% | +3.65% |

| Rcarbon_trading (−50%) | Medium impact | −6.10% | −4.58% |

| DoD (%) | ratio | ΔNPV (×108 CNY) | ΔEmissions (×106 kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | 0 | 5.95 | 3.92 |

| 0.25 | 6.30 | 3.96 | |

| 0.50 | 6.66 | 4.00 | |

| 0.75 | 7.03 | 4.08 | |

| 1 | 7.54 | 7.70 | |

| 50 | 0 | 5.20 | 4.15 |

| 0.25 | 5.56 | 4.19 | |

| 0.50 | 5.92 | 4.21 | |

| 0.75 | 6.29 | 4.25 | |

| 1 | 6.81 | 8.02 | |

| 60 | 0 | 6.33 | 4.23 |

| 0.25 | 6.70 | 4.26 | |

| 0.50 | 7.06 | 4.30 | |

| 0.75 | 7.43 | 4.35 | |

| 1 | 7.94 | 8.24 |

| DoD (%) | ratio | ΔNPV (×108 CNY) | ΔEmissions (×106 kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | 0 | 1.40 | 8.00 |

| 0.25 | 1.77 | 8.03 | |

| 0.50 | 2.14 | 8.18 | |

| 0.75 | 2.50 | 8.20 | |

| 1 | 3.01 | 12.20 | |

| 50 | 0 | 0.85 | 8.75 |

| 0.25 | 1.23 | 8.77 | |

| 0.50 | 1.58 | 8.80 | |

| 0.75 | 1.95 | 8.92 | |

| 1 | 2.46 | 13.00 | |

| 60 | 0 | 0.30 | 9.30 |

| 0.25 | 0.66 | 9.31 | |

| 0.50 | 1.03 | 9.32 | |

| 0.75 | 1.39 | 9.40 | |

| 1 | 1.88 | 13.80 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qiu, J.; Zhao, W.; Tian, H.; Li, M.; Han, W. Sustainable Port Horizontal Transportation: Environmental and Economic Optimization of Mobile Charging Stations Through Carbon-Efficient Recharging. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 681. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120681

Qiu J, Zhao W, Tian H, Li M, Han W. Sustainable Port Horizontal Transportation: Environmental and Economic Optimization of Mobile Charging Stations Through Carbon-Efficient Recharging. World Electric Vehicle Journal. 2025; 16(12):681. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120681

Chicago/Turabian StyleQiu, Jie, Wenxuan Zhao, Hanlei Tian, Minhui Li, and Wei Han. 2025. "Sustainable Port Horizontal Transportation: Environmental and Economic Optimization of Mobile Charging Stations Through Carbon-Efficient Recharging" World Electric Vehicle Journal 16, no. 12: 681. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120681

APA StyleQiu, J., Zhao, W., Tian, H., Li, M., & Han, W. (2025). Sustainable Port Horizontal Transportation: Environmental and Economic Optimization of Mobile Charging Stations Through Carbon-Efficient Recharging. World Electric Vehicle Journal, 16(12), 681. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120681