Rapid Evaluation of Off-Highway Powertrain Architectures

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Objectives of This Study

2. Literature Review

2.1. Custom Analysis with General-Purpose Math Tools

2.2. ADVISOR

2.3. ALPHA

2.4. AMESIM

2.5. AUTONOMIE

2.6. AVL Cruise M

2.7. GT Suite

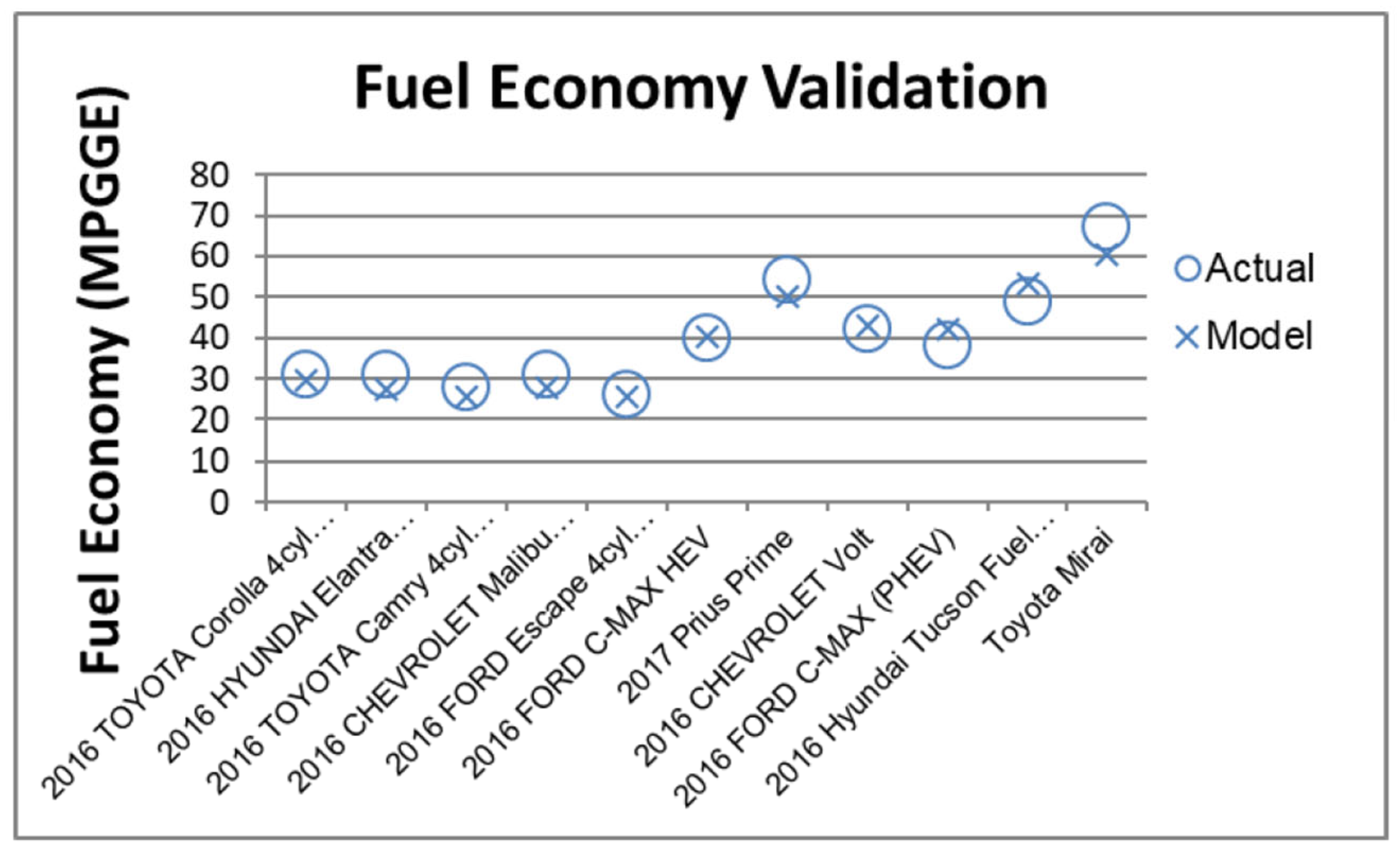

2.8. FASTSIM

2.9. Summary of Simulation Tools

3. Methods

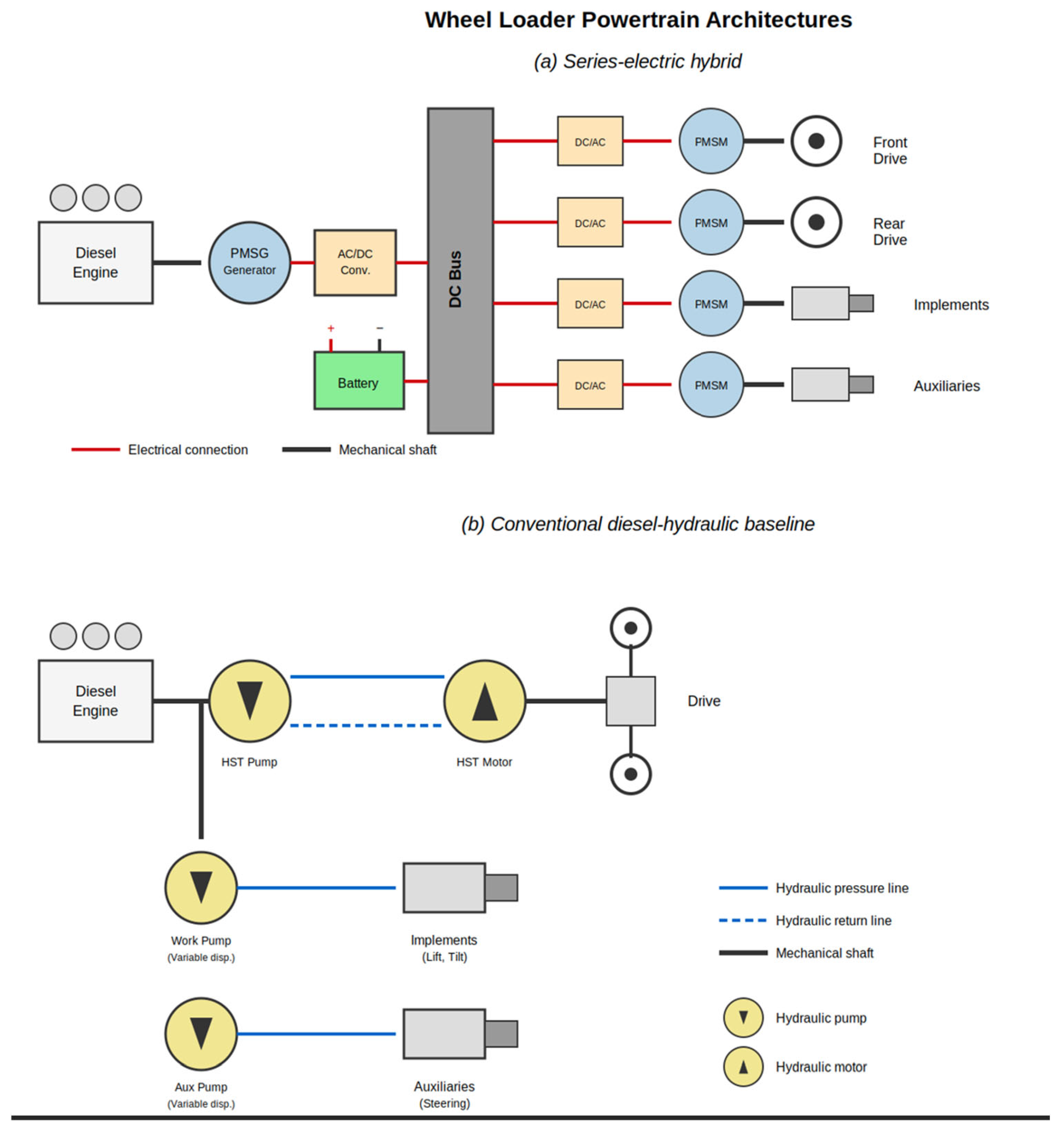

3.1. Allam and Linjama Method (Benchmark)

3.2. Dedicated Software Tools

3.3. ePOP Concept

3.3.1. Efficiency Assumption—Inverters

3.3.2. Efficiency Assumption—eMotors

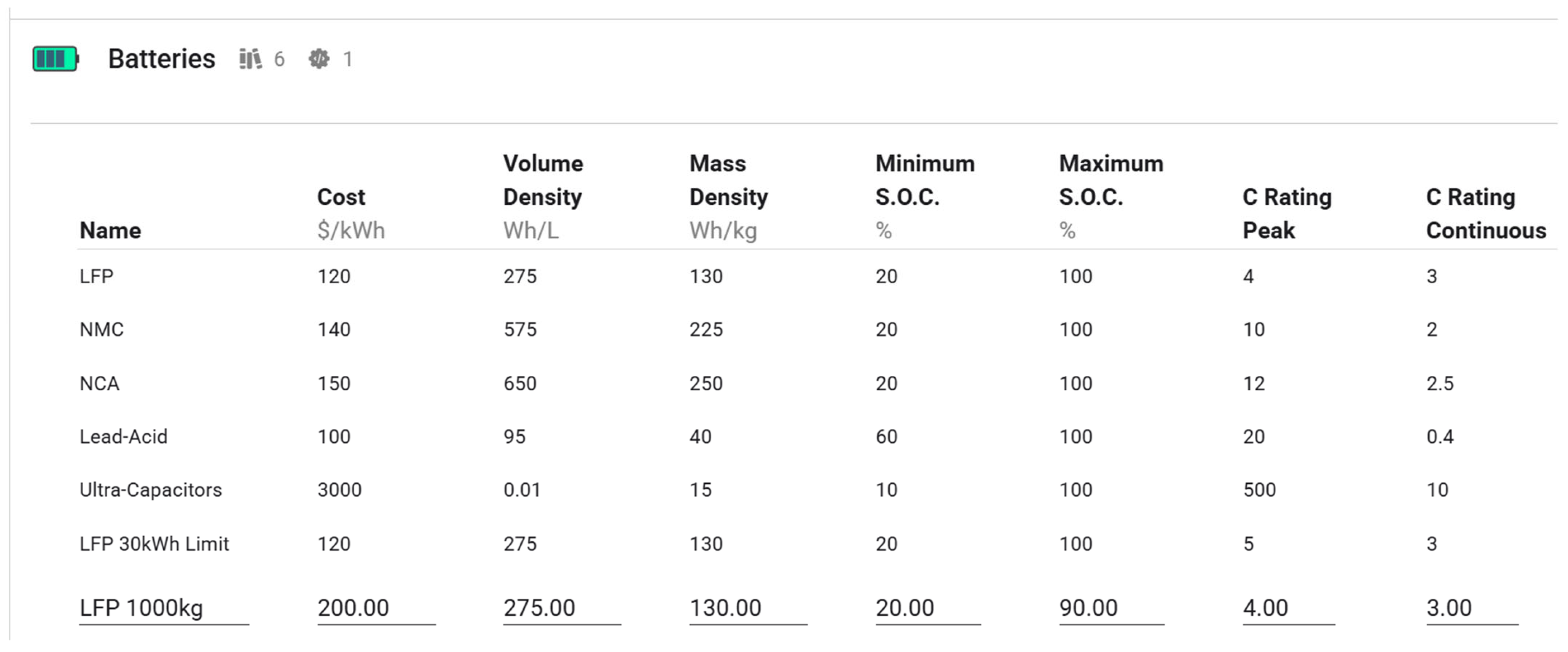

3.3.3. Efficiency Assumption—Batteries

3.3.4. Efficiency Assumption—ICE (Internal Combustion Engine)

3.3.5. Efficiency Assumption—Cooling

3.3.6. Efficiency Assumption—Transmission

3.3.7. Efficiency Assumption—Hydraulic Pumps and Motors

3.3.8. Proposed Improvement—BSFC Adjustment for Load

| BSFC | = | Brake-specific fuel consumption (kg/kWh). |

| BSFCmin | = | Minimum BSFC at optimal operating point (kg/kWh). |

| BSFCop | = | BSFC at the operating point (kg/kWh). |

| ISFC | = | Indicated specific fuel consumption (kg/kWh). |

| IMEP | = | Indicated mean effective pressure (bar). |

| BMEP | = | Brake mean effective pressure (bar). |

| BMEPmax | = | Maximum BMEP at rated power (bar). |

| BMEPop | = | BMEP at the operating point (bar) |

| FMEP | = | Friction mean effective pressure (bar). |

| Pop | = | Power at the operating point (kW). |

| Prated | = | Rated (maximum) power (kW). |

| IMEPmax | = | Maximum IMEP at rated power (bar). |

| IMEPop | = | IMEP at the operating point (bar). |

3.3.9. Efficiency Assumptions—Summary

3.4. Case Studies

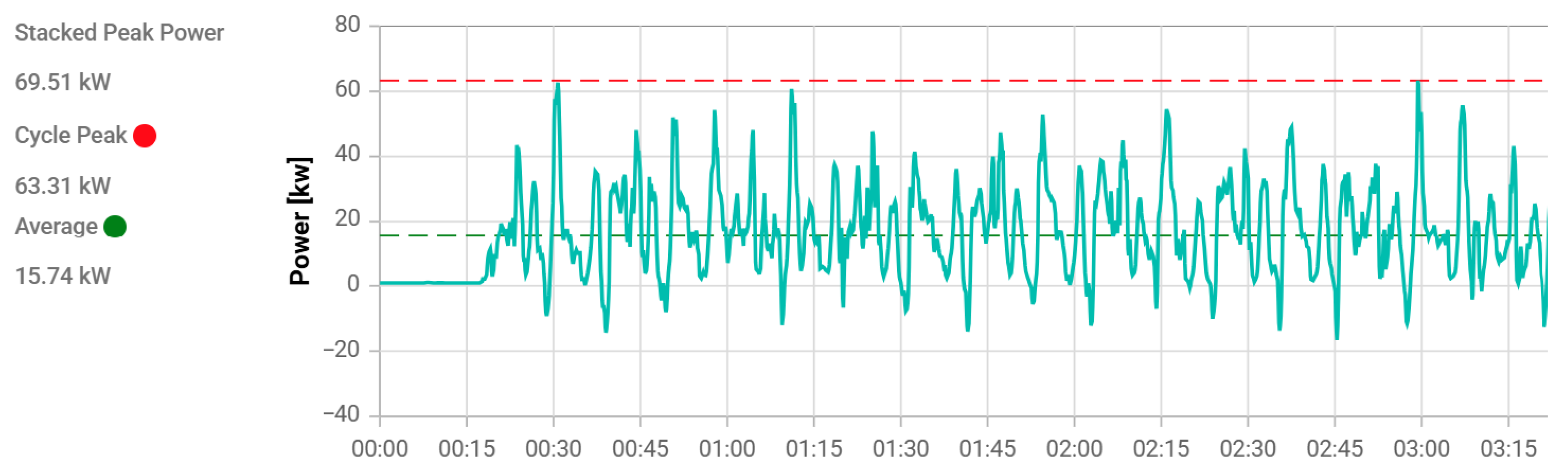

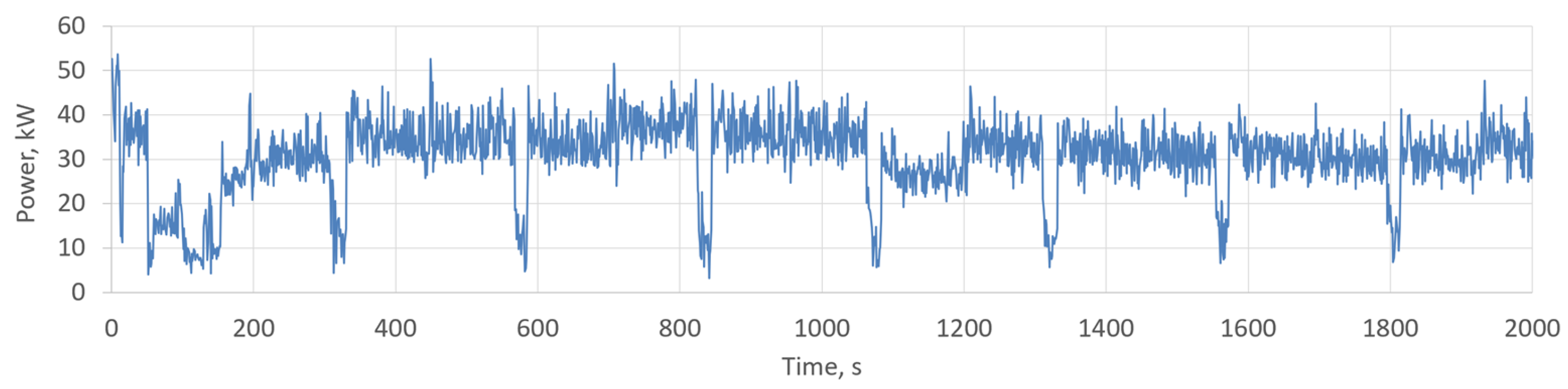

3.4.1. Wheel Loader Analysis

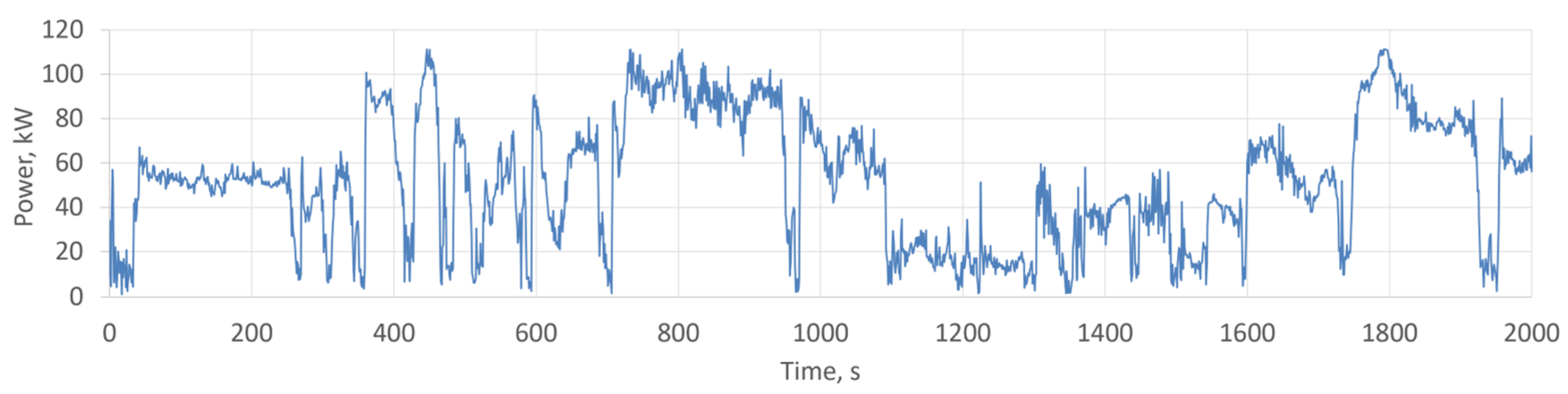

3.4.2. Tractor Analysis

4. Results

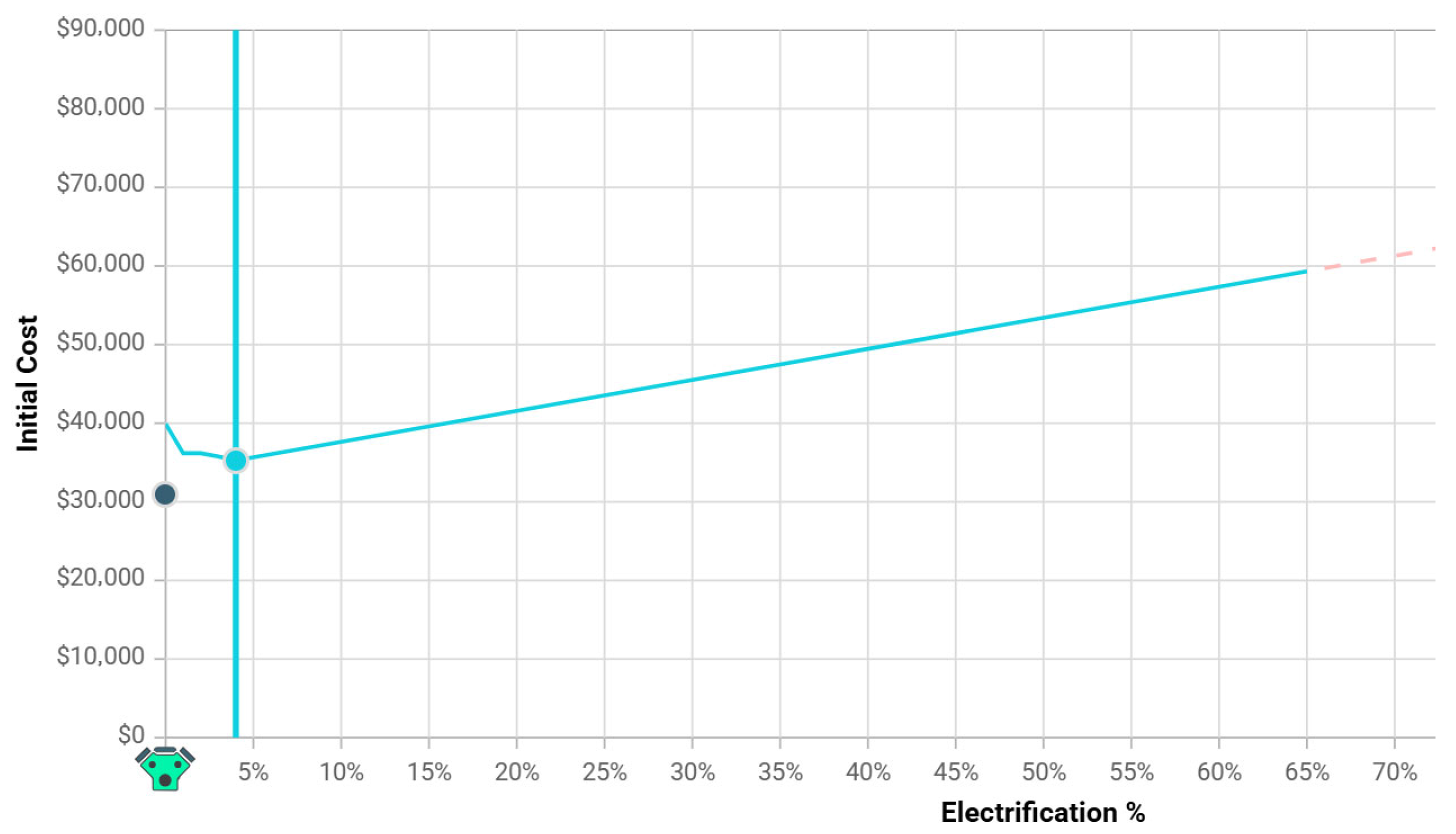

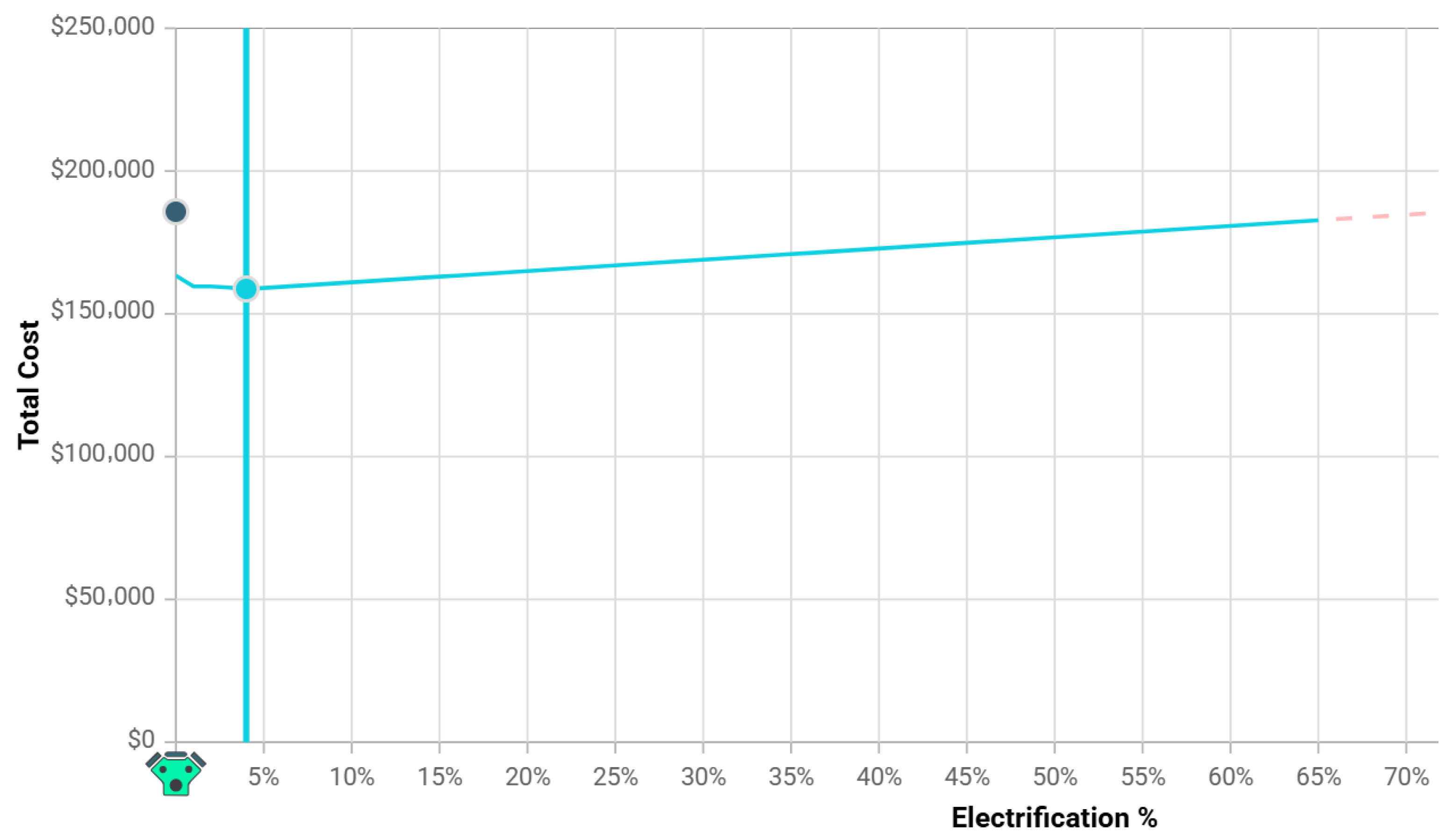

4.1. Wheel Loader Analysis—ePOP Concept

4.2. Tractor Analysis—ePOP Concept

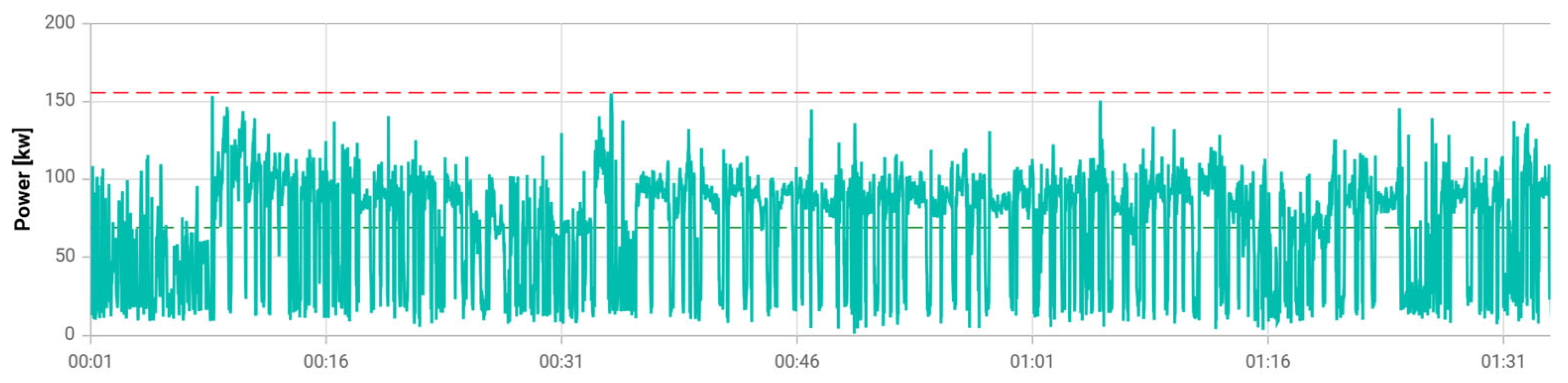

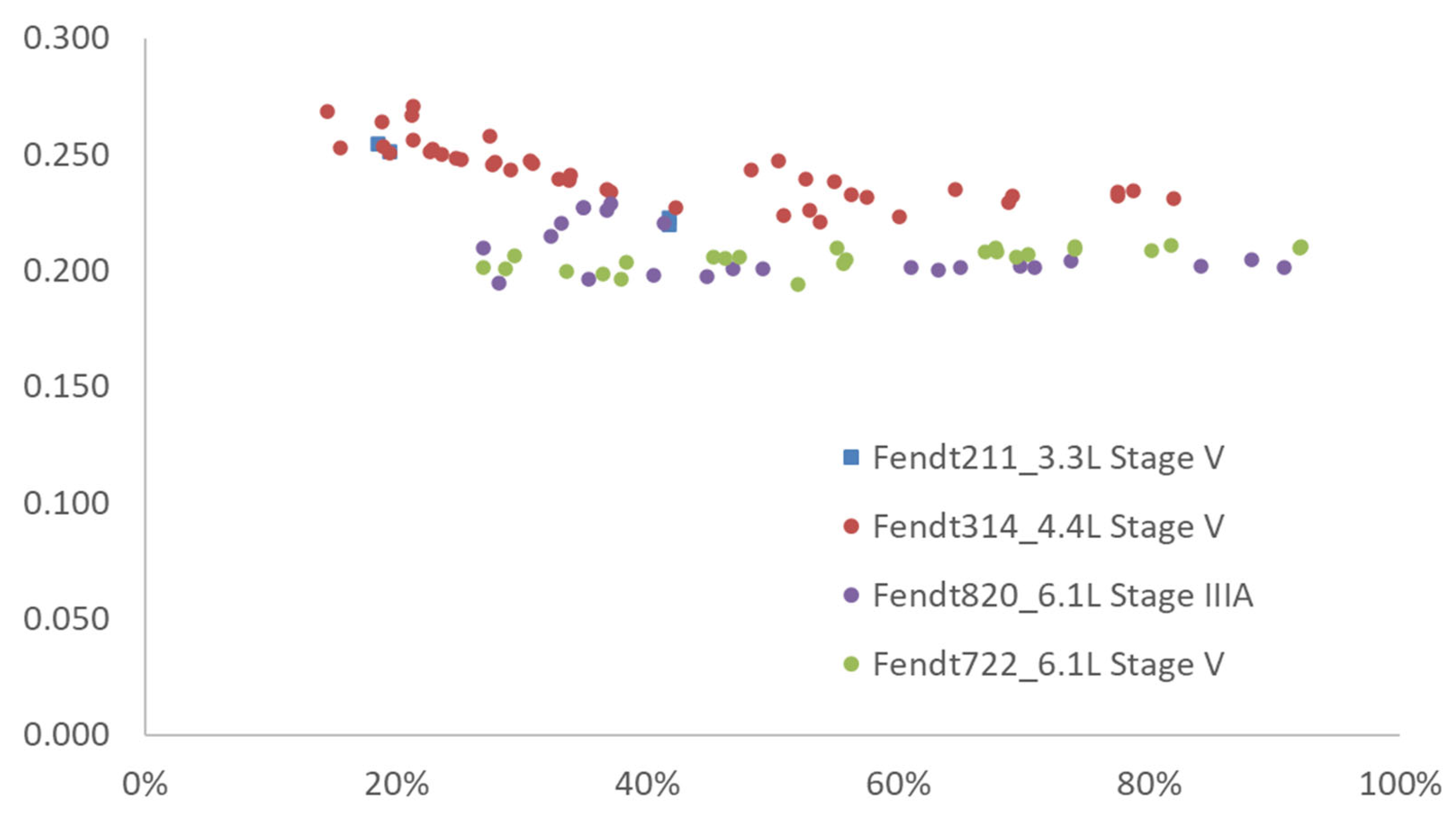

4.3. BSFC Correction

5. Discussion

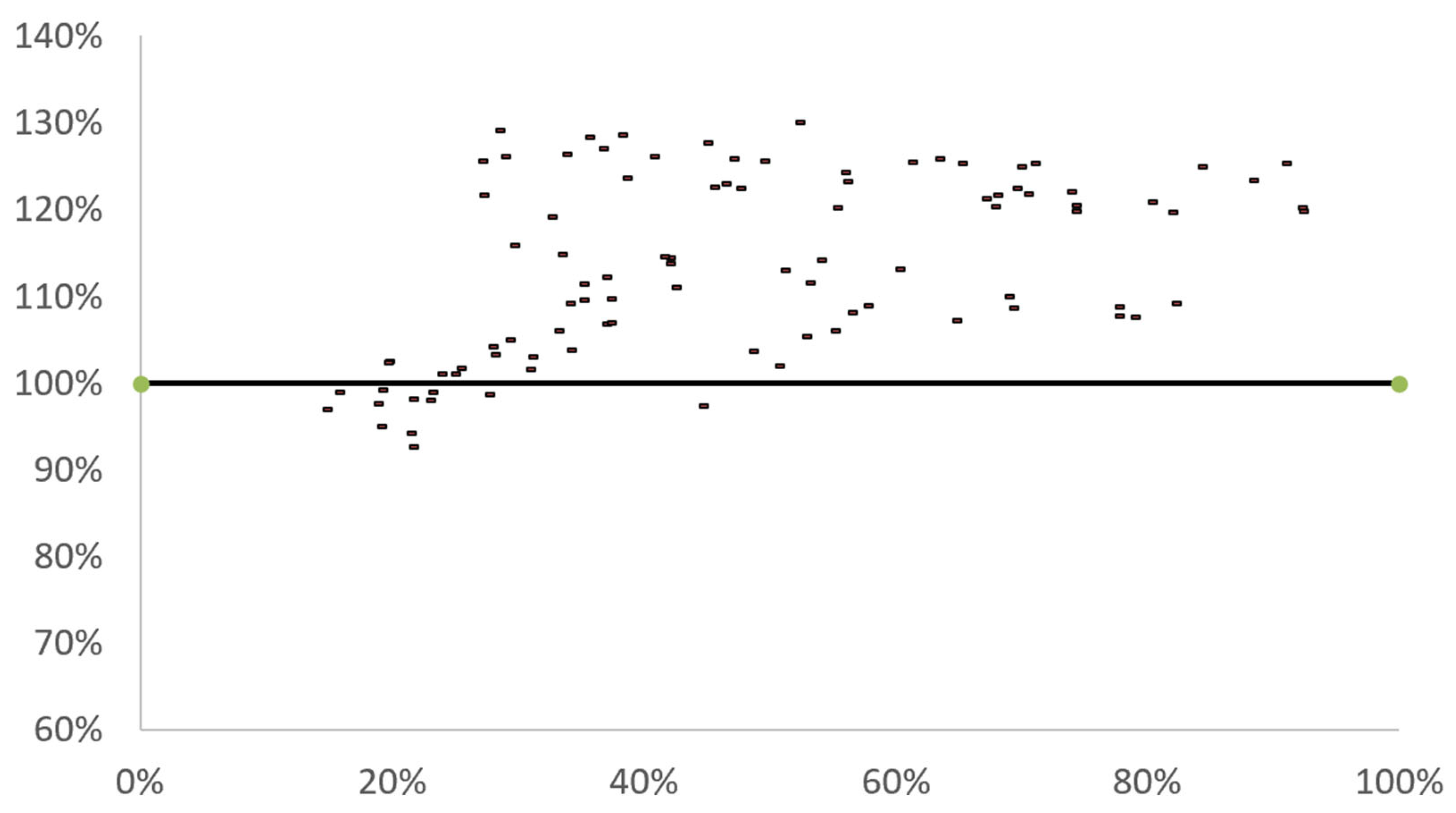

5.1. Accuracy of Fuel Prediction

5.2. Causes of Fuel Prediction Errors

5.3. Methods to Reduce Fuel Prediction Errors

5.4. Evaluation of Hybridization Benefits

5.5. Comparison with Alternative Methods

- The use of engine efficiency maps enables the benefits of operating-point modification to be included, whereas ePOP Concept assumes constant efficiency. It also introduces engine-specific BSFC data, which reduces error significantly.

- The control strategy can be defined, e.g., when to switch off the engine of a hybrid and run from battery power only.

- As well as engine data, other component-specific characterization data can be used, reducing errors, but at the cost of some effort in data collection.

5.6. Future Development Work

- Scaling algorithms to account automatically for engine scale effects, improving the generic assumptions for engine BSFC.

- Simple 1-dimensional engine BSFC modeling to account for load dependency

- Similar efficiency modeling approaches applied to other components, including inverters, e-motors, hydraulics, transmissions and engine accessories.

- Automatic elimination of infeasible conditions, e.g., electrical or ICE components tending to zero size.

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BEV | Battery Electric Vehicle. |

| BMEP | Brake Mean Effective Pressure. |

| BSFC | Brake-Specific Fuel Consumption. |

| BTE | Brake Thermal Efficiency. |

| CAN-BUS | Controller Area Network Bus. |

| CNG | Compressed Natural Gas. |

| CVT | Continuously Variable Transmission. |

| EGR | Exhaust Gas Recirculation. |

| FMEP | Friction Mean Effective Pressure. |

| GaN | Gallium Nitride. |

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite System. |

| HEV | Hybrid Electric Vehicle. |

| HST | Hydrostatic Transmission. |

| ICE | Internal Combustion Engine. |

| IGBT | Insulated-Gate Bipolar Transistor. |

| IMEP | Indicated Mean Effective Pressure. |

| ISFC | Indicated Specific Fuel Consumption. |

| NREL | National Renewable Energy Laboratory. |

| OEM | Original Equipment Manufacturer. |

| PHEV | Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle. |

| PTO | Power Take-Off. |

| RMS | Root Mean Square. |

| SiC | Silicon Carbide. |

| TCO | Total Cost of Ownership. |

Appendix A

| Parameter | Units |

| time | s |

| Machine_Speed | m/s |

| Machine_Direction | – |

| Diesel_w | rad/s |

| Diesel_TorqueEstimate | Nm |

| Diesel_FuelRate | L/h |

| Diesel_PowerEstimate | W |

| LiftCylinder_x | m |

| LiftCylinder_v | m/s |

| LiftCylinder_pA | Pa |

| LiftCylinder_pB | Pa |

| LiftCylinder_F | N |

| LiftCylinder_Q_A | m3/s |

| LiftCylinder_Q_B | m3/s |

| TiltCylinder_x | m |

| TiltCylinder_v | m/s |

| TiltCylinder_pA | Pa |

| TiltCylinder_pB | Pa |

| TiltCylinder_F | N |

| TiltCylinder_Q_A | m3/s |

| TiltCylinder_Q_B | m3/s |

| StabilizerCylinder_x | m |

| StabilizerCylinder_v | m/s |

| StabilizerCylinder_Q_A | m3/s |

| StabilizerCylinder_Q_B | m3/s |

| StabilizerCylinder_pA | Pa |

| StabilizerCylinder_pB | Pa |

| StabilizerCylinder_F | N |

| LiftValve_Q_PA | m3/s |

| LiftValve_Q_BT | m3/s |

| LiftValve_Q_PB | m3/s |

| LiftValve_Q_AT | m3/s |

| TiltValve_Q_PA | m3/s |

| TiltValve_Q_BT | m3/s |

| TiltValve_Q_PB | m3/s |

| TiltValve_Q_AT | m3/s |

| WorkPump_w | rad/s |

| WorkPump_pP | Pa |

| WorkPump_FlowEstimate | m3/s |

| WorkPump_TorqueEstimate | Nm |

| WorkPump_AngleEstimate | – |

| WorkPump_ShaftPowerEst | W |

| WorkPump_HydraulicPowerEst | W |

| WorkPump_ErrorFlag | – |

References

- Götz, K.; Pointner, M.; Mayr, L.; Mailhammer, S.; Lienkamp, M. Electrify the Field: Designing and Optimizing Electric Tractor Drivetrains with Real-World Cycles. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beligoj, M.; Scolaro, E.; Alberti, L.; Renzi, M.; Mattetti, M. Feasibility Evaluation of Hybrid Electric Agricultural Tractors Based on Life Cycle Cost Analysis. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 28853–28867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagnelöv, O.; Larsson, G.; Nilsson, D.; Larsolle, A.; Hansson, P.-A. Performance comparison of charging systems for autonomous electric field tractors using dynamic simulation. Biosyst. Eng. 2020, 194, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajunen, A.; Kivekäs, K.; Freyermuth, V.; Vijayagopal, R.; Kim, N. Simulation of Alternative Powertrains in Agricultural Tractors. In Proceedings of the 36th International Electric Vehicle Symposium and Exhibition (EVS36), Sacramento, CA, USA, 11–14 June 2023; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto Prada, D.; Vijayagopal, R.; Costanzo, V. Opportunities for Medium and Heavy Duty Vehicle Fuel Economy Improvements Through Hybridization; SAE Technical Paper 2021-01-0717; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, D.; de Castro, R.; Ehsani, R.; Vougioukas, S.; Wei, P. Unlocking the potential of electric and hybrid tractors via sensitivity and techno-economic analysis. Appl. Energy 2025, 377, 124545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkilä, M.; Huova, M.; Tammisto, J.; Linjama, M.; Tervonen, J. Fuel efficiency optimization of a baseline wheel loader and its hydraulic hybrid variants using dynamic programming. In Proceedings of the BATH/ASME 2018 Symposium on Fluid Power and Motion Control FPMC2018, Bath, UK, 12–14 September 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linjama, M.; Huova, M.; Tammisto, J.; Tervonen, J.; Ahola, V. 6-ton wheel loader short Y-cycle data for 440 seconds loading of gravel. Zenodo 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, M.; Linjama, M. Optimisation of series electric hybrid wheel loader energy management strategies using dynamic programming. Int. J. Heavy Veh. Syst. 2025, 32, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.W.; Mi, C.; Emadi, A. Modeling and Simulation of Electric and Hybrid Vehicles. Proc. IEEE 2007, 95, 729–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, K.A.; Doorlag, M.; Barba, D. Modeling of a Conventional Mid-Size Car with CVT Using ALPHA and Comparable Powertrain Technologies; SAE Technical Paper 2016-01-1141; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.; Liu, Z.; Cardoso, R.; Busquets, E. Electrification of a compact skid-steer loader—Redesign of the hydraulic functions. In River Publishers Series in Transport, Logistics and Supply Chain Management; River Publishers: Gistrup, Denmark, 2024; Chapter 12; Available online: https://www.riverpublishers.com/pdf/ebook/chapter/RP_9788770047456C12.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Moawad, A.; Xu, B.; Pagerit, S.; Nieto Prada, D.; Vijayagopal, R.; Sharer, P.; Islam, E.; Kim, N.; Phillips, P.; Rousseau, A. AutonomieAI: An efficient and deployable vehicle energy consumption estimation toolkit. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2025, 139, 104569. [Google Scholar]

- EPA/NHTSA. Vehicle System Simulation to Support NHTSA CAFE Standards for the Draft TAR; NHTSA Workshop: San Diego, CA, USA, 11 November 2018. Available online: https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.gov/files/anl-nhtsa-workshop-vehicle-system-simulation.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Tang, B. Simulational energy analyses of different transmission (automated manual transmission vs continuously variable transmission) selection effects on fuel cell hybrid electric vehicles’ energetic performance. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 75, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.L.; Jia, Y.Z.; Lei, Y.L.; Fu, Y.; Liu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.J. Car Fuel Economy Simulation Forecast Method Based on CVT Efficiencies Measured from Bench Test. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2018, 31, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. The development of hybrid electric vehicle control strategy based on GT-SUITE and Simulink. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Intelligent Systems Research and Mechatronics Engineering, Zhengzhou, China, 11–13 April 2015; pp. 2056–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooker, A.; Gonder, J.; Lopp, S.; Ward, J. FASTSim Validation Report; NREL Technical Report NREL/TP-5400-81097; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2022. Available online: https://docs.nrel.gov/docs/fy22osti/81097.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Baker, C.; Moniot, M.; Brooker, A.; Wang, L.; Wood, E.; Gonder, J. Future Automotive Systems Technology Simulator (FASTSim) Validation Report—2021; NREL/TP-5400-81097; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.osti.gov/biblio/1828851 (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Su, H.; Zhang, L.; Meng, D.; Li, Y.; Han, N.; Xia, Y. Modeling and Evaluation of SiC Inverters for EV Applications. Energies 2022, 15, 7025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.A.; Hsieh, M.-F. Performance Analysis of Permanent Magnet Motors for Electric Vehicles (EV) Traction Considering Driving Cycles. Energies 2018, 11, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Li, D.; Zou, Y. Energy efficiency of lithium-ion batteries: Influential factors and long-term degradation. J. Energy Storage 2023, 74, 109386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friso, D. Brake Thermal Efficiency and BSFC of Diesel Engines: Mathematical Modeling and Comparison between Diesel Oil and Biodiesel Fueling. Appl. Math. Sci. 2014, 8, 6515–6528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heywood, J.B. Internal Combustion Engine Fundamentals; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1988; ISBN 0-07-028637-X. [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson, N.; Johansson, K.H. Modelling and control of auxiliary loads in heavy vehicles. Int. J. Control 2006, 79, 479–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saetti, M.; Mattetti, M.; Varani, M.; Lenzini, N.; Molari, G. On the power demands of accessories on an agricultural tractor. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 206, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, H. Gearbox Efficiency; Blom Engineering Blog, Sweden. 2020. Available online: https://hblom.se/summer-scope-inspire/ (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Wileman, C. Heavy-Duty Vehicle Transmission Benchmarking—Volvo I-Shift 12-Speed Automated Manual Transmission; Tech Report, DOT HS 813 620; National Highway Traffic Safety Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2025.

- Ryu, I.H.; Kim, D.C.; Kim, K.U. Power Efficiency Characteristics of a Tractor Drive Train. Trans. ASAE 2003, 46, 1481–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Park, J.; Kim, K. Gear Train Power Loss Characteristics for Agricultural Tractor Transmission. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2017, 42, 248–256. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, M.E.; Dasgupta, K.; Ghoshal, S. Comparison of the Efficiency of the High Speed Low Torque Hydrostatic Drives Using Bent Axis Motor: An Experimental Study. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E J. Process Mech. Eng. 2015, 231, 650–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sârbu, F.A.; Arnăut, F.; Deaconescu, A.; Deaconescu, T. Theoretical and Experimental Research Concerning the Friction Forces Developed in Hydraulic Cylinder Coaxial Sealing Systems Made from Polymers. Polymers 2024, 16, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwemin, P.; Fiebig, W. The Influence of Radial and Axial Gaps on Volumetric Efficiency of External Gear Pumps. Energies 2021, 14, 4468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauranne, H. Effect of Operating Parameters on Efficiency of Swash-Plate Type Axial Piston Pump. Energies 2022, 15, 4030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobsinger, T.; Hieronymus, T.; Brenner, G. A CFD Investigation of a 2D Balanced Vane Pump Focusing on Leakage Flows and Multiphase Flow Characteristics. Energies 2020, 13, 3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stosiak, M.; Yatskiv, I.; Prentkovskis, O.; Karpenko, M. Reduction of Pressure Pulsations over a Wide Frequency Range in Hydrostatic Systems. Machines 2025, 13, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.-M.; Kim, W.-S.; Kim, Y.-S.; Baek, S.-Y.; Kim, Y.-J. Development of a simulation model for HMT of a 50 kW class agricultural tractor. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpenko, M. Investigation of Energy Efficiency of Mobile Machinery Hydraulic Drives. Ph.D. Thesis, Vilnius Gediminas Technical University, Vilnius, Lithuania, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, E.; Brennan, S. Diesel Engine Characterization and Performance Scaling via Brake Specific Fuel Consumption Map Dimensional Analysis. In Proceedings of the ASME 2019 Dynamic Systems and Control Conference, Park City, Utah, USA, 8–11 October 2019; Volume 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyehara, O.A. Factors that Affect BSFC and Emissions for Diesel Engines: Part 1—Presentation of Concepts; SAE Technical Paper 870343; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suijs, W.; Verhelst, S. Scaling Performance Parameters of Reciprocating Engines for Sustainable Energy System Optimization Modelling. Energies 2023, 16, 7497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzella, L.; Onder, C.H. Introduction to Modeling and Control of Internal Combustion Engine Systems, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009; ISBN 978-3-642-10774-0. [Google Scholar]

- Rakopoulos, C.D.; Giakoumis, E.G. Second-law analyses applied to internal combustion engines operation. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2006, 32, 2–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youtube Video. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mAyLr9AO_rQ (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Götz, K.; Kusuma, A.; Dörfler, A.; Lienkamp, M. Agricultural Load Cycles: Tractor Mission Profiles From Recorded GNSS and CAN Bus Data. Data Brief. 2025, 60, 111494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD Code 2 abstract for Fendt 724 Vario Gen6 4WD with Deutz TCD 6.1 L6. Available online: https://site.unibo.it/trattori-certificati-ocse/en/year-2022/fendt-724-vario-gen6 (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- OECD Code 2 Abstract, Fendt 820 Vario TMS, COM IIIa. Available online: https://webfs.oecd.org/TADWEB/agriculture/data/tractor/2010/2.1-2010_Abstract_Eng.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- OECD Code 2 Abstract, Fendt 314 Vario Gen4. Available online: https://site.unibo.it/trattori-certificati-ocse/en/year-2022/fendt-314-vario-gen4 (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Fendt 300 Vario S4 brochure (AGCO 4.4 L). Available online: https://www.tractorrepairs.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/300Vario-S4-BROCHURE.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- DLG PowerMix datasheet for Fendt 211 S Vario. Available online: https://pruefberichte.dlg.org/filestorage/PowerMix_Datenblatt_Fendt-211-S-Vario_en.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- DEUTZ AG—AGRI Engine Series “TCD 4.1/6.1” PDF. Retrieved via DEUTZ Engine Finder (Product Group: Agricultural Machinery). Available online: https://www.deutz.com/fileadmin/user_upload/produkte/kraftstoffe_der_zukunft/tr_0199_99_01218_6_en.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Nebraska Tractor Test Laboratory. OECD Tractor Test 3298 for Fendt 314 Vario Gen4 Diesel. Nebraska Summary 1215; University of Nebraska-Lincoln: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2022. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tractormuseumlit (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Design for Circularity with ePOP: A Software Solution built for Powertrain Optimisation of Performance, Cost and Sustainability—Wiktor Dotter (ZeBeyond Ltd.), David Hind (Drive System Design), CTI Symposium Germany (Dec 2023). Available online: https://www.zebeyond.com/publications/design-for-circularity-with-epop (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Electric Drivetrain Architecture Optimisation for Autonomous Vehicles Based on Representative Cycles—Thomas Holdstock, Michael Bryant (Drive System Design), CTI Symposium, Berlin (Dec 2018). Available online: https://www.zebeyond.com/publications/electric-drivetrain-architecture-optimisation-for-autonomous-vehicles-based-on-representative-cycles (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- U.S. Energy Information Administration. Annual Energy Outlook 2025 (AEO2025). 15 April 2025. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/aeo/ (accessed on 5 December 2025).

| Method/Tool | User Expertise | Software Cost | Outputs | Data Gathering/ Setup Effort | Reported Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Custom analysis | Expert | MATLAB | Custom | High (weeks–months) | 2–5% |

| ADVISOR | Skilled | MATLAB + License | Efficiency | Moderate (days–weeks) | ~5% |

| ALPHA | Skilled | MATLAB + License | Efficiency | Moderate (days–weeks) | Within 5% |

| AMESIM | Expert | High (commercial) | Efficiency | High (weeks) | Not reported |

| Autonomie | Skilled | MATLAB + License | Efficiency | Moderate (days–weeks) | Within 2% |

| AVL Cruise M | Expert | Very High | Efficiency | High (weeks) | Within 5.5% |

| GT-Suite | Expert | Very High | Efficiency | High (weeks) | Not reported |

| FASTSIM | Moderate | Free | Efficiency | Low–Moderate (days) | Within 10.5% |

| Potential Gap: | Low | Low | Efficiency + Cost, Weight and Package | Minimal | Within 10% |

| Component Type | Typical Throughput Efficiency Range (%) | Primary Cause of Variation | Main Physical Sources of Loss |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bent-axis axial piston motor | 75–92% | Mostly pressure-dependent | Leakage; friction; torque losses |

| Swash-plate axial piston pump | 80–93% | Mostly pressure-dependent | Leakage; friction; viscous drag |

| External gear pump | 70–88% | Mostly pressure-dependent | Gap leakage; viscous drag; gear/bearing losses |

| Balanced vane pump | 65–85% | Speed- and pressure-dependent | Leakage; viscous drag; cavitation |

| Hydraulic cylinder | 75–95% | Strongly speed-dependent | Seal friction; mixed lubrication |

| Component Type | Typical Losses (% of Power) | Primary Cause of Variation | Main Physical Sources of Loss |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inverter | 1–25% | Current dependent; efficiency decreases at low current and near high-current limits | Switching losses; conduction losses; gate drive losses |

| Electric Motor | 4–20% | Load dependent; mild speed dependency | Copper losses; iron losses; inverter-induced harmonics; mechanical friction |

| Battery Pack (Round Trip Efficiency) | 12–27% | Current (power) dependent | Internal resistance (I2R losses); charge-transfer losses; thermal effects |

| Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) | 61–79% | Load dependent; mild speed dependency. | Combustion losses; heat transfer; pumping loss; friction; accessory loads. |

| Cooling/Accessories | 2–15% (heavy truck) | Power dependent | Cooling fan, steering, brakes |

| Mechanical Transmission | 4–16% | Torque dependent; mild speed dependency | Gear mesh losses; bearing friction; oil churning and windage |

| Hydraulic Components (Pumps, Motors, Cylinders) | 5–35% | Load dependent | Leakage; seal friction; viscous drag; cavitation at high speed |

| “A” Component | Size | Cost (USD) | “B” Component | Size | Cost $ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydraulic System | 20,188 | Electrical System | 29,963 | ||

| ICE | 91.7 kW | 8201 | ICE | 41 kW | 4949 |

| Cooler 1 | 2.1 kW | 82 | Cooler 1 | 1 kW | 50 |

| Fuel Tank | 368 | Fuel Tank | 293 | ||

| Total Initial Cost USD | 28,839 | 35,255 | |||

| Fuel Cost (10 yr) USD | 154,914 | 123,436 | |||

| Total TCO (10 yr) USD | 183,753 | 158,681 |

| Cycle Average Power (Measured), kW | Fuel Usage (Measured), L | Fuel Usage (Predicted), L | BSFC (Measured), g/kWh | BSFC (Predicted), g/kWh |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15.74 kW | 61.2 | 59.6 | 406 | 395.2 |

| Engine Model | Vehicle Model | Minimum BSFC kg/kWh Engine Only/PTO |

|---|---|---|

| AGCO 3.3 L I3 Stage V | Fendt 211 | 0.212/0.293 |

| AGCO 4.4 L I4 Stage V | Fendt 314 | 0.226/0.277–0.303 |

| Deutz 6.1 L I6 Stage IIIA | Fendt 820 | 0.195/0.240 |

| Deutz 6.1 L I6 Stage V | Fendt 722 | 0.198/0.244 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tull de Salis, R. Rapid Evaluation of Off-Highway Powertrain Architectures. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 671. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120671

Tull de Salis R. Rapid Evaluation of Off-Highway Powertrain Architectures. World Electric Vehicle Journal. 2025; 16(12):671. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120671

Chicago/Turabian StyleTull de Salis, Rupert. 2025. "Rapid Evaluation of Off-Highway Powertrain Architectures" World Electric Vehicle Journal 16, no. 12: 671. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120671

APA StyleTull de Salis, R. (2025). Rapid Evaluation of Off-Highway Powertrain Architectures. World Electric Vehicle Journal, 16(12), 671. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120671