1. Introduction

As autonomous driving technology progresses toward Level 4 (L4) automation, human drivers are increasingly relying on intelligent assistance systems [

1]. One of the most common driving behaviors in dynamic traffic environments is lane changing, and the effectiveness of lane-change decision systems directly affects the credibility and acceptance of autonomous vehicles [

2]. However, current systems face significant challenges in decision-making, especially in complex scenarios [

3]. Research shows that rule-based autonomous vehicles often make unnecessary secondary lane changes after overtaking, which can compromise safety [

4]. According to U.S. NHTSA accident reports, about 10–15% of lane-change incidents involving autonomous vehicles are linked to ‘premature lane return’ [

5]. In these cases, vehicles may return to their lane without maintaining a safe distance, increasing the risk of rear-end or side collisions. This mechanical decision-making process is starkly different from the judgment-based decisions made by human drivers. As a result, it not only reduces traffic flow efficiency but also creates confusion and safety hazards for other drivers [

6]. The core issue with ‘mechanical’ lane changes lies in the rigid, context-independent logic used by current systems. Unlike human drivers, who consider personal preferences and environmental factors, autonomous systems follow a fixed decision-making cycle: overtaking for the sake of overtaking, and returning for the sake of returning. Integrating human driving style characteristics into intelligent decision-making systems could address these issues effectively.

Different drivers may adopt varying driving strategies under identical road conditions, influenced by factors such as personality, environment, and experience [

7]. Current research on driving styles primarily employs traditional behavioral indicators [

8], statistical scoring models [

9], unsupervised clustering methods [

10], and supervised machine learning techniques [

11] to represent and quantify driving behavior effectively. Several studies have been conducted on this topic. In the field of driving style research, several studies have proposed methods for recognizing and categorizing driving styles. For example, Deng et al. developed a driving style recognition method based on ensemble learning and enhanced clustering analysis. By combining the iForest anomaly detection algorithm with the Bisecting K-Means clustering technique, they identified three driver types: cautious, average, and aggressive [

12]. Similarly, Lyu et al. established a driving style recognition framework that utilizes machine learning models and natural driving data from vehicles equipped with Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS). Their study found that aggressive drivers maintained smaller headway distances and times compared to cautious and moderate drivers [

13]. Additionally, Wu Yiping et al., using natural driving data from Beijing taxis, employed the K-Means algorithm to classify driver styles. Their analysis revealed that cautious drivers exhibited stable driving with excellent speed control, conservative drivers maintain stability on straight roads but tended to drive faster on curves, and aggressive drivers showed significant fluctuations in speed [

14].

Game theory provides a framework for modeling decision-making in vehicle interactions. By applying game theory principles, it is possible to simulate human-like decision-making and develop effective lane-changing strategies for autonomous vehicles [

15]. For instance, Kita et al. developed a game-theory model to describe the interactions between merging and straight-through vehicles, explicitly considering their mutual influence on traffic flow [

16]. Qu et al. advanced this by incorporating dynamic traffic factors into their modeling of autonomous vehicle lane-changing strategies. Their work provides a scientific explanation of the decision-making processes involved in autonomous lane changes [

17]. Currently, the integration of reinforcement learning and game theory provides new insights for tackling decision-making challenges in complex, dynamic environments. Wang et al. have proposed decision-making mechanisms based on cooperative game theory and joint deep learning optimization. When tasks involve multiple agents, these mechanisms can reduce energy consumption and improve efficiency while achieving objectives [

18]. Additionally, by combining game theory with reinforcement learning, Hu et al. have introduced a novel framework called Game-Theoretic Risk-Shaping Reinforcement Learning (GTR2L) for safe autonomous driving. This framework enhances decision-making in complex environments and effectively reduces collision risks [

19].

Building upon the existing research outlined above, this paper focuses on the critical challenge of anthropomorphic lane-changing decisions in intelligent driving. To overcome the limitations of existing mechanical decision-making paradigms—such as ‘returning to the original lane’—this study constructs a closed-loop decision framework integrating driving style feature analysis, game-theoretic interaction modeling, and dynamic reference line switching. The human-like lane-changing strategy generated by this framework significantly enhances the compatibility of autonomous driving behavior with human driving conventions, providing new methodological support for improving the system’s generalizability and robustness.

3. Human-like Lane-Changing Strategies

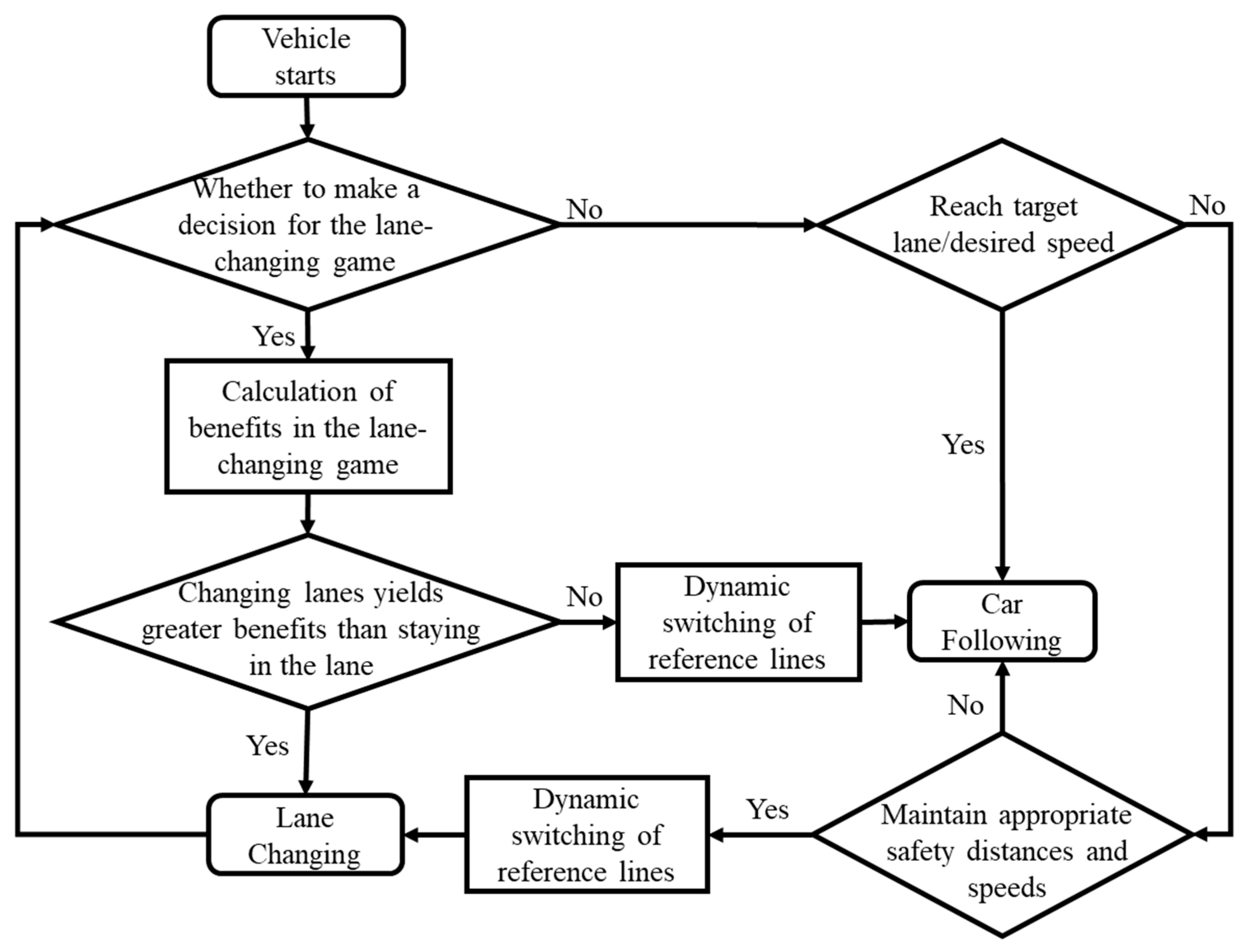

3.1. Human-like Lane-Changing Decision-Making Framework

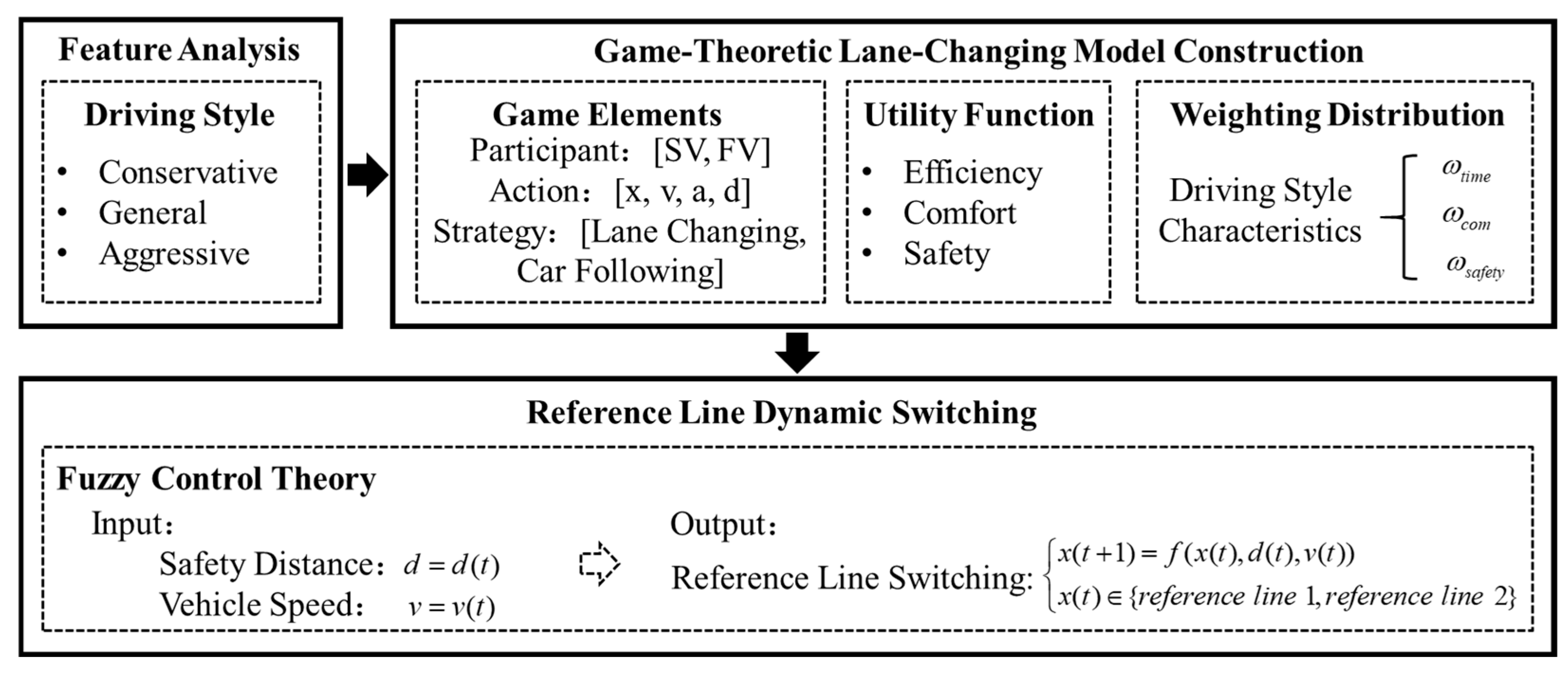

The architecture consists of three main modules: the driving style feature analysis module, the game decision model construction module, and the reference line dynamic switching module. Firstly, the feature analysis module conducts a detailed examination of the typical characteristics and distribution patterns of different driving styles. Second, the game decision model construction module lists all the elements involved in the decision-making process. It constructs utility functions that balance safety, comfort, and traffic efficiency, assigning appropriate weightings based on the results from the driving style analysis. Finally, the reference line dynamic switching module uses vehicle spacing and speed as inputs to dynamically adjust the reference line. The organic combination of the three elements has jointly enabled the construction of the human-like lane-changing decision model. Vehicle Human-like lane-changing decision architecture considering the characteristics of driving style is illustrated in

Figure 2.

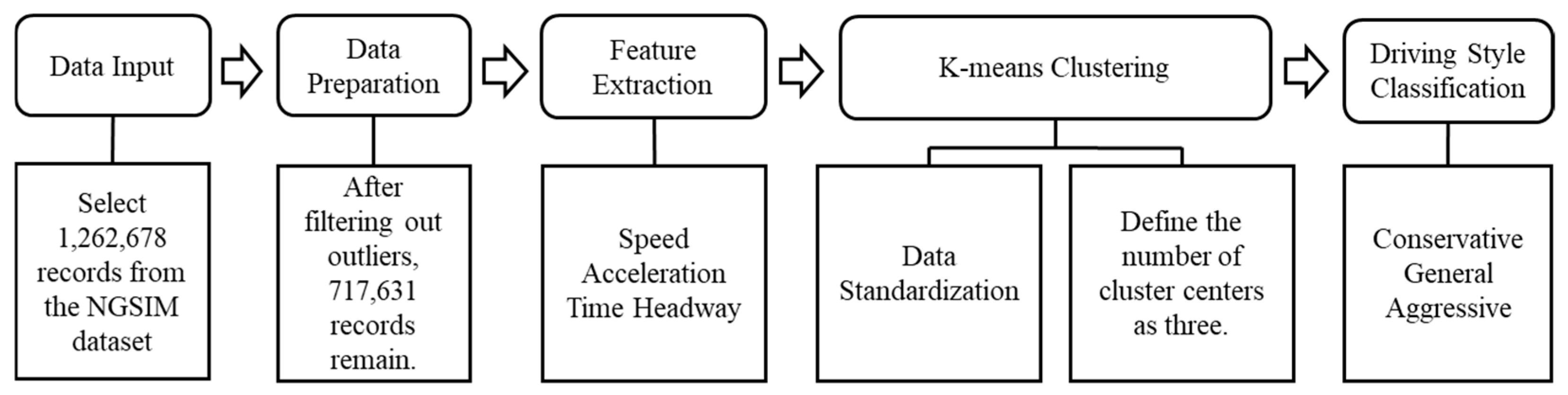

3.2. Analysis of Driving Style Characteristics

This study analyzes vehicle trajectory data from the I-80 highway segment using the NGSIM trajectory dataset, publicly released by the U.S. Federal Highway Administration. An unsupervised anomaly detection algorithm, Isolation Forest [

21], was applied for data preprocessing, identifying and removing 545,047 anomalous records from a total of 1,262,678 raw entries. This left 717,631 high-quality data points for subsequent clustering analysis. Features with varying measurement scales—specifically speed, acceleration, and vehicle distance—were then normalized using Z-score transformation. This process converted them into a standard normal distribution with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1, thereby mitigating the impact of scale differences on the clustering results.

To classify driving styles, this study uses the K-means clustering algorithm. The optimal number of clusters is determined by evaluating both the elbow rule and the contour coefficient method [

22,

23]. The distortion curve from the elbow rule shows a clear inflection point at k = 3, while the highest average contour coefficient (0.9003) is also achieved at k = 3, indicating optimal cohesion and separation for the clustering results at this cluster count. As a result, the study categorizes driving styles into three types: Aggressive, Normal, and Conservative. The driving style clustering process is shown in

Figure 3.

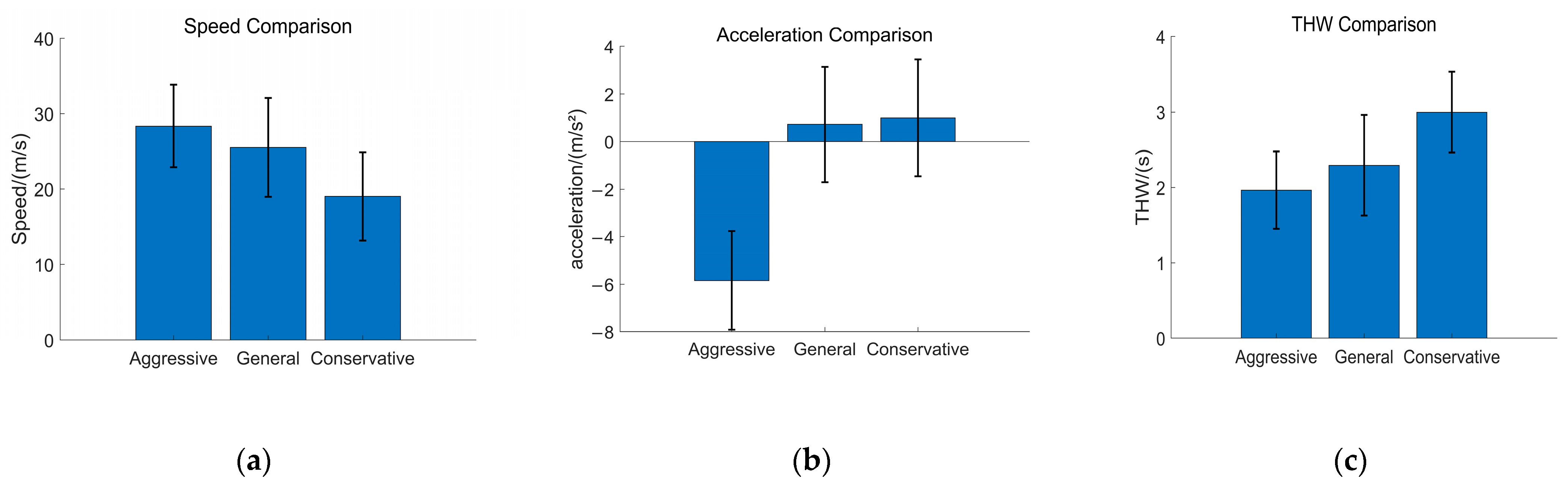

Extract the speed, acceleration and headway time from the dataset, calculate their mean and standard deviation, and obtain the distribution map of driving style and driving characteristics. Distribution of various driving styles and driving characteristics is illustrated in

Figure 4.

The calculation results of driving characteristics for three different driving styles are shown in

Table 1.

Driving style reflects a driver’s inherent risk perception, aggressiveness, and operational habits. These traits influence both longitudinal following behavior and lateral lane-changing decisions. This study quantitatively examines the behavioral differences among three distinct driving styles. Aggressive drivers tend to have higher average speeds, greater acceleration, and shorter headways, prioritizing travel efficiency. General drivers strike a balance between comfort and efficiency, maintaining moderate speeds, steady acceleration, and medium headways. Conservative drivers prioritize safety, opting for lower speeds, minimal acceleration, and maximum headways.

Building on these characteristics, and integrating insights from traffic psychology [

24] and driving behavior studies [

25], the core features of typical driving styles are further defined.

Table 2 describes each driving style and its corresponding traits.

3.3. Construction of the Game Lane-Changing Model

Following driving style analysis, game theory principles are introduced [

26], treating the self-driving vehicle (SV) and the following vehicle (FV) in the target lane as game participants. The objective is to design a payoff function based on driving safety, passenger comfort, and traffic flow efficiency. Subsequently, different weighting coefficients are assigned to the objective function based on driving style characteristics, ultimately achieving the construction of a game-based lane-changing model.

3.3.1. Definition of Basic Elements of Game Theory

This paper focuses primarily on ‘mechanical’ lane-changing behavior based on predefined rules. When changing lanes, the driving conditions of the self-driving vehicle (SV) and the following vehicle (FV) in the target lane are the key considerations. The basic elements of the game are as follows:

Self-driving Vehicle (SV): The decision-making entity, optimizing the lane-changing strategy through game theory

Following Vehicle (FV) in the target lane: The interacting object, whose behavior affects the safety of lane-changing

- (2)

Action

Related parameters: position , speed , acceleration , lateral offset , longitudinal distance .

- (3)

Strategy

Self-driving Vehicle (SV):

Following Vehicle (FV) in the target lane:

3.3.2. Game Outcome Analysis

- (1)

Comfort Benefits

Driving comfort is closely linked to the smoothness of a vehicle’s lateral motion. In this study, we quantify driving comfort by measuring the cumulative lateral displacement of the vehicle. Larger lateral displacements are associated with lower levels of comfort. Therefore, comfort benefits can be defined as:

For each moment

, the lateral position is

, and the cumulative lateral displacement is expressed as:

where

is the lateral position of the vehicle at time

,

is the reference position of the vehicle at time

, and

,

are the start and end times of the lane change.

- (2)

Safety Benefits

The driving style characteristics table indicates that headway distance significantly influences driving behavior, with aggressive drivers tending toward shorter headway distances and higher speeds. This paper uses headway distance as a measure of vehicle safety benefits, defined by the following safety benefit function:

where

denotes the head-to-head time distance between the vehicle and the preceding vehicle at the lane-change moment, while

denotes the head-to-head time distance between the vehicle and the preceding vehicle at the initial moment of the lane change.

The calculation formula for the headway of the vehicle’s front is as follows:

where

represents the headway between vehicles, and

denotes the speed of the following vehicle.

- (3)

Traffic Efficiency Benefits

The traffic efficiency benefit assesses how lane-changing decisions affect overall traffic flow. It is influenced by two key factors: the time taken to complete a lane change and the resulting longitudinal displacement of vehicles. In this study, vehicle travel time is used to quantify travel efficiency. Therefore, the travel efficiency benefit function is:

where

represents the time required for a vehicle to reach the lane-change endpoint when selecting a certain strategy, while

denotes the time required for a vehicle to reach the lane-change endpoint while maintaining its original state of travel.

- (4)

Total Benefits

After determining the comfort benefits, safety benefits, and traffic efficiency benefits of lane changes for the vehicle, these three benefits are combined to calculate the vehicle’s total benefit.

where

represents the weight of comfort benefits,

represents the weight of safety benefits, and

represents the weight of traffic efficiency benefits, satisfying the relationship

.

The game payoff matrix [

27] for the interaction between the self-vehicle A and the vehicle B2 in the target lane is shown in

Table 3.

3.3.3. Weighting Distribution of Objective Functions in Game Models

This study preliminarily characterizes the lane-changing behaviors of drivers with different driving styles by assigning distinct weight coefficients and desired speeds, with the objective function weights calculated using a data-driven approach. Through feature standardization and weight bias algorithms, each driving style is ensured to have one dominant decision dimension and two auxiliary dimensions. The computational process is as follows:

- (1)

Data normalization using the Min-Max normalization method [

28].

For positively correlated indicators (such as average velocity and average THW):

For negatively correlated indicators (such as acceleration standard deviation):

where

represents the original data, while

and

denote the minimum and maximum values in the data, respectively.

- (2)

Determine Dominant Characteristics

Table 4 presents the main characteristics of driving styles and their corresponding relationships.

- (3)

Apply weighting bias to increase the weight of corresponding dominant characteristics for different driving styles.

- (4)

Weight normalization

Scaling:

where

is the sum of all weights, and

is the weight of a specific feature.

The calculated weight coefficients for the driving style objective function are shown in the table below [

29,

30].

Table 5 shows the weight coefficients calculated based on driving styles.

3.4. Reference Line Dynamic Switching Mechanism Design

Based on fuzzy control theory, a reference line switching mechanism jointly driven by safety distance and vehicle speed is established. By constraining vehicle speed and driving safety distance, dynamic switching of the reference line is achieved. Its core logic can be expressed as:

The input variables are: distance between vehicles and vehicle speed ; the output variable is: reference line switching status ( as primary reference line; as secondary reference line).

The lane-change reference line switching rules are as follows:

When maneuvering occurs, if the benefit of changing lanes is less than that of staying in the current lane, and the vehicle’s speed reaches the target speed while the distance

between the vehicle and the rear vehicle in the target lane is less than the minimum safe distance, the reference line switches to the current lane. The vehicle will not change lanes and will return to the original lane.

where

represents the desired speed, and

denotes the minimum safe distance.

When no maneuvering occurs, if the distance

between the vehicle and the vehicle ahead in the current lane does not meet the minimum safe lane-change distance, the reference line switches to the current lane. When the distance between the two vehicles meets the safe lane-change distance, the reference line switches to the target lane.

where

represents the desired speed, and

denotes the safe distance interval for lane changes.

The primary reference line defines the optimal driving path within the current lane, ensuring that the vehicle travels safely and smoothly. The secondary reference line supports multi-objective optimization by balancing driving safety, comfort, and traffic efficiency once the desired speed is reached. By continuously monitoring the vehicle’s dynamics and surrounding environment, it smoothly transitions between the primary and secondary reference lines, simulating human lane-change decisions and avoiding frequent or premature lane shifts that would resemble non-human driving patterns.

In summary, the human-like lane-change decision-making process is illustrated in

Figure 5.

4. Simulation Experiments and Results Analysis

4.1. Simulation Experiment Description

This paper uses joint simulation with PreScan 8.5, Carsim 2019.1 and Matlab2021b to model a three-lane lane-changing scenario in the same direction. PreScan constructs the scenario and simulates stationary obstacle vehicles, Carsim provides the dynamic model for the main vehicle, and Matlab/Simulink implements the human-like lane-change decision model. By setting obstacle vehicles to stationary speeds, the simulation replicates a steady state in traffic flow theory, eliminating the effects of complex traffic fluctuations. This setup allows for a clearer validation of the proposed human-like lane-change strategy’s effectiveness across different scenarios.

Three distinct simulation scenarios were designed to represent the driving habits of operators with different driving styles. The proposed human-like lane-change decision method was compared with Baidu Apollo 6.0’s dynamic programming approach by analyzing lateral displacement–time curves, longitudinal displacement–time curves, velocity-time curves, and steering angle variation plots. Both methods used identical controllers, validating the superiority of the proposed human-like lane-change decision method.

4.2. Simulation Experiment Comparative Analysis

4.2.1. Simulation Parameter Settings

The initial vehicle state parameters for simulation are set as shown in the table below. Scenario 1 configures the self-driving vehicle A and obstacle vehicles B1, with the lead vehicle’s desired speed set to 10 m/s. Scenarios 2 and 3 configure the self-driving vehicle A and obstacle vehicles B1, B2, and B3, with the self-driving vehicle’s desired speeds set to 15 m/s and 20 m/s, respectively. The initial parameters for the simulation are shown in

Table 6.

4.2.2. Analysis of Simulation Scenario Lane-Changing Strategies

- (1)

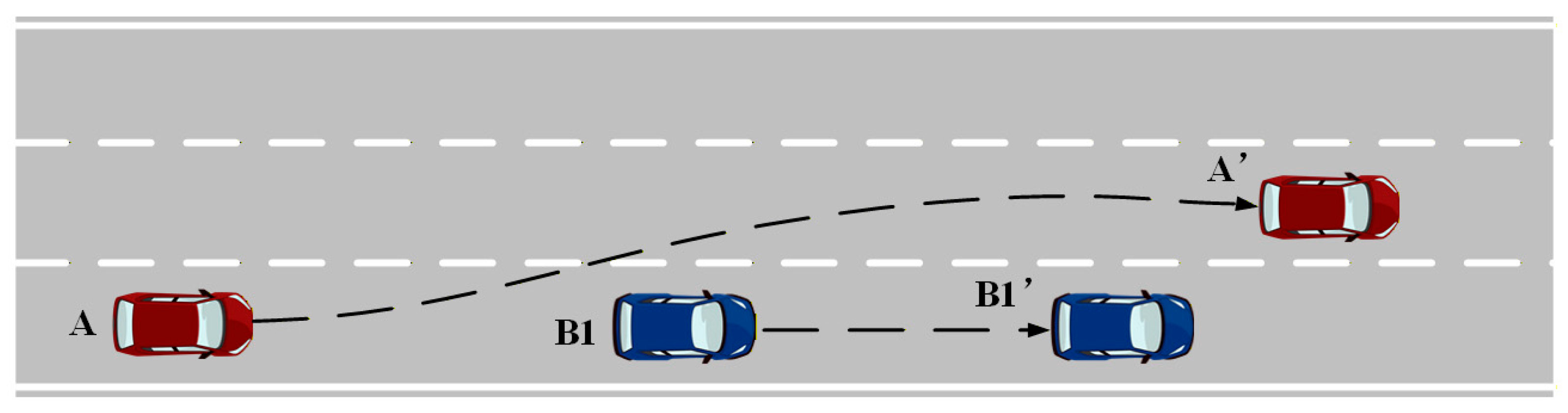

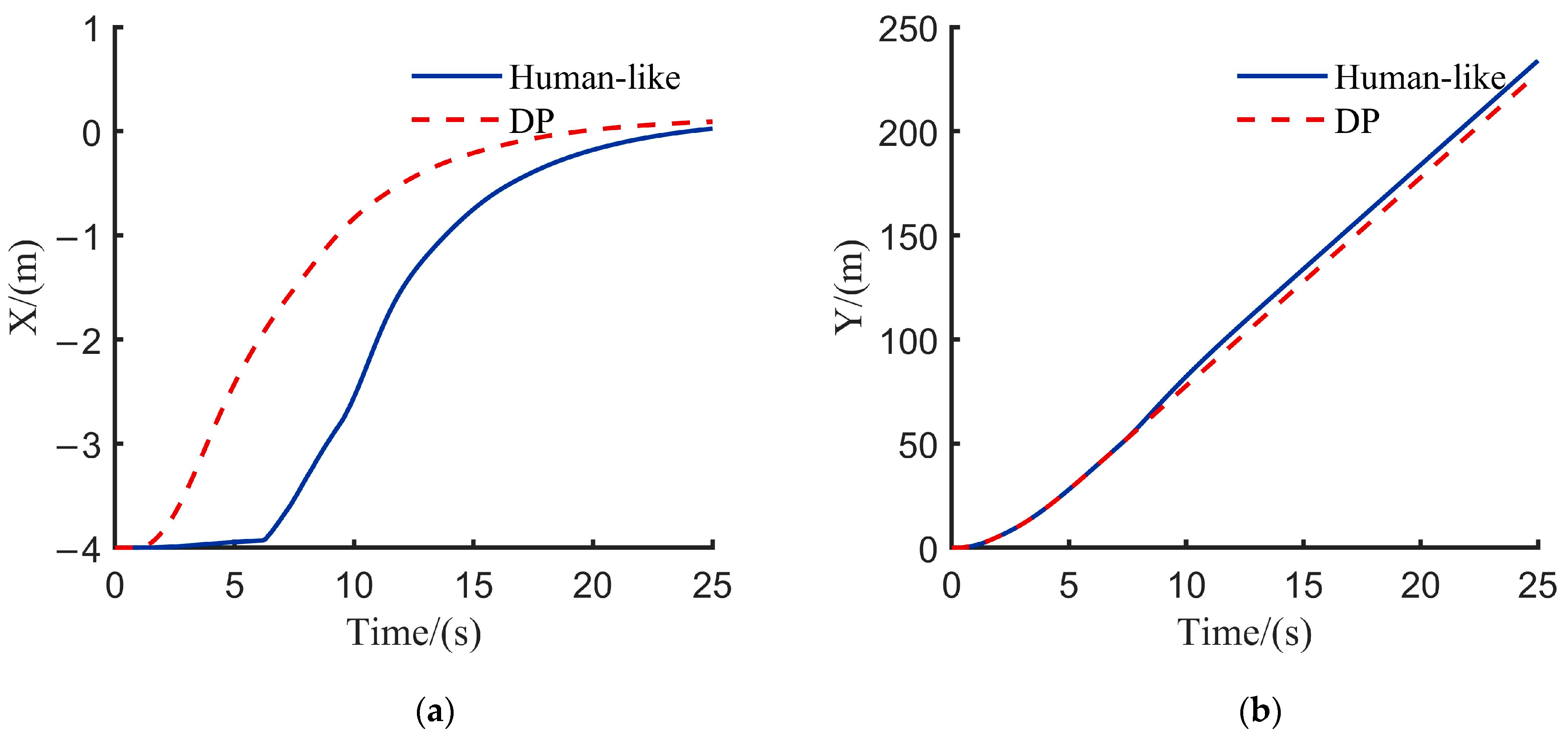

Scenario One

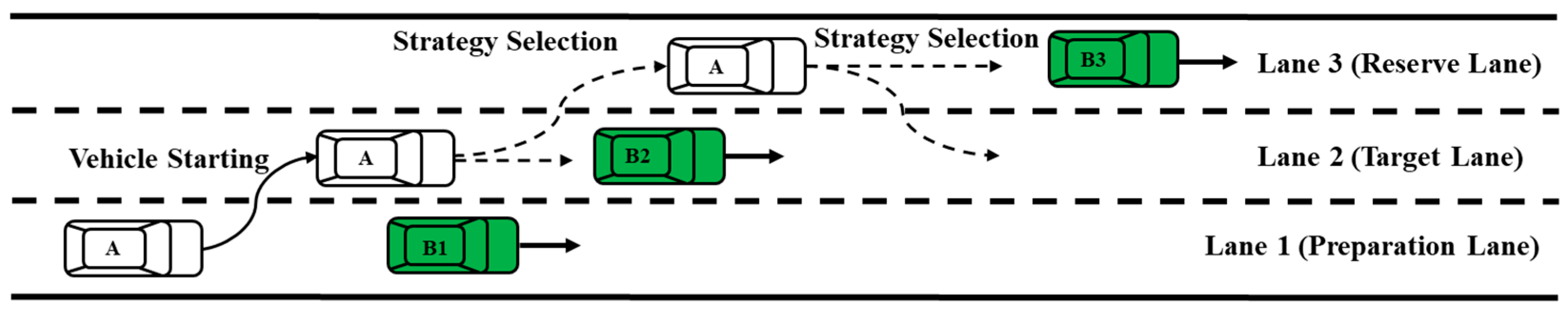

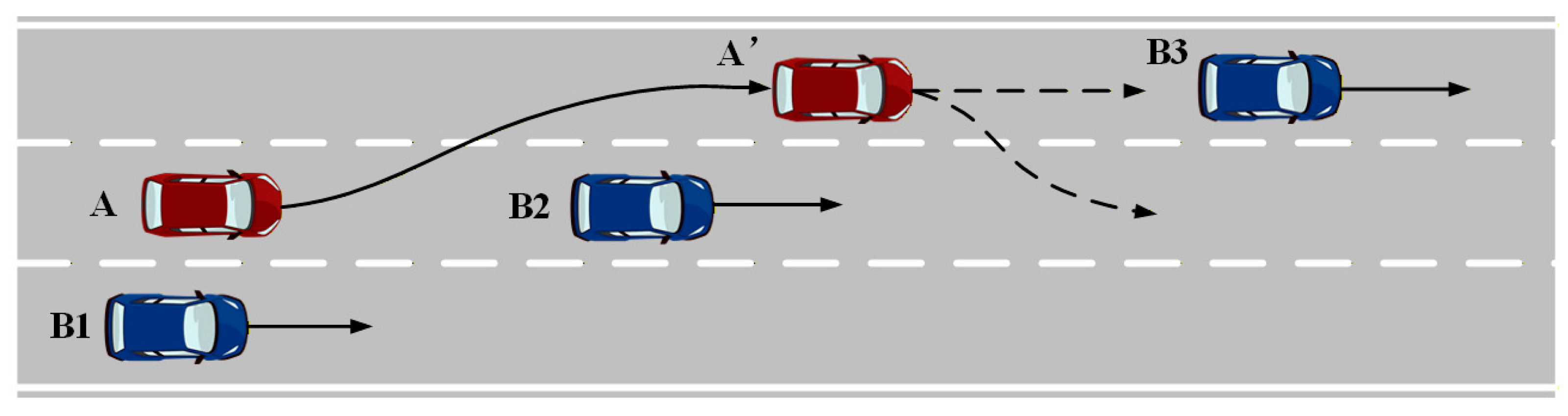

In the scenario depicted in

Figure 6, the vehicle is in the initial stage of movement, and there are no following vehicles in the target lane. No game behavior has occurred. The following is a comparison chart of different driving parameters under two decision-making planning methods. Scenario 1 Comparison of vehicle driving parameters under different decision-making methods is illustrated in

Figure 7.

Simulation results highlight the key difference in decision-making intelligence between the two models. The dynamic programming model’s rigid lane-change decision at t = 2 s exposes the limitations of its ‘open-loop optimization’ approach, which fails to adapt to environmental changes after the decision, thus posing safety risks. In contrast, the anthropomorphic model’s dynamic reference line switching mechanism employs a ‘closed-loop probing’ strategy. By introducing a continuous evaluation phase during decision-making, this mechanism simulates the human driver’s cognitive process of confirming safety windows. It builds decision confidence on ongoing data rather than a single calculation, significantly enhancing decision robustness. The subsequent active deceleration after the lane change further demonstrates the control system’s closed-loop feedback capability, enabling a smooth and safe transition from ‘completing an action’ to ‘achieving a safe, stable state.’

- (2)

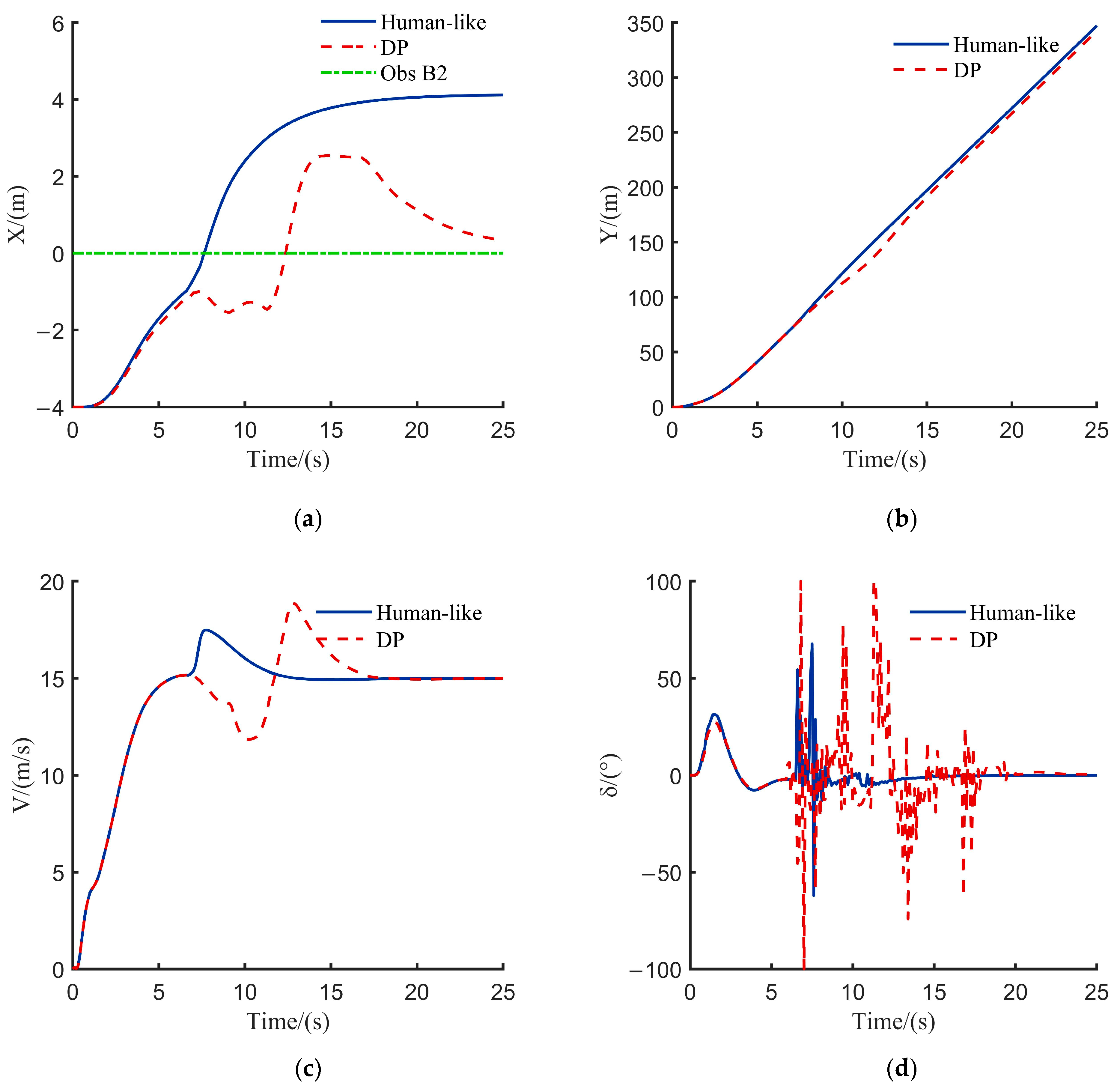

Scenario Two

In the scenario depicted in

Figure 8, after completing the initial start phase, the autonomous vehicle enters the strategy selection phase. Target vehicle A engages in a game-theoretic interaction with the rear vehicle B2 in the target lane. The following figure compares driving parameters under two different decision planning methods. Scenario 2 Comparison of vehicle driving parameters under different decision-making methods is illustrated in

Figure 9.

Simulation results highlight the key difference between the two models: the DP model executes a predefined ‘overtake-return’ action, while this model makes ‘lane-keeping’ decisions based on game-theoretic payoffs, evaluating the speeds of both vehicles. The core advantage lies in this model’s ability to perform continuous multi-objective optimization, demonstrating superior behavioral intelligence. In terms of performance, this model reduces speed standard deviation by 2.64%, indicating better speed maintenance. The steering angle change rate drops by 75.28%, providing clear evidence of a significant improvement in trajectory smoothness and control comfort. These results confirm that, through human-like decision-making, this model outperforms traditional DP methods in both fluidity and comfort.

- (3)

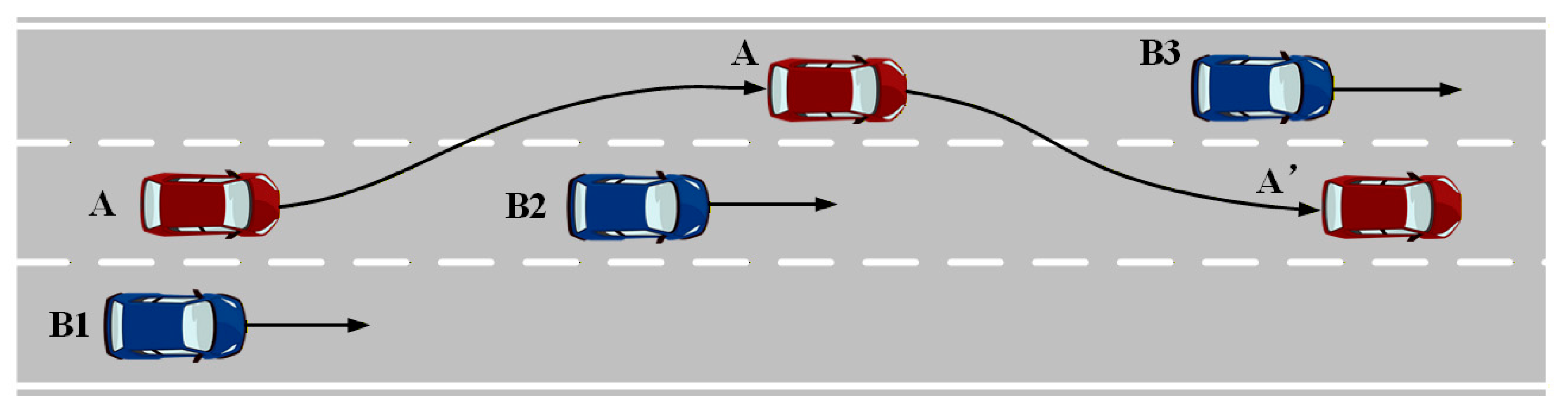

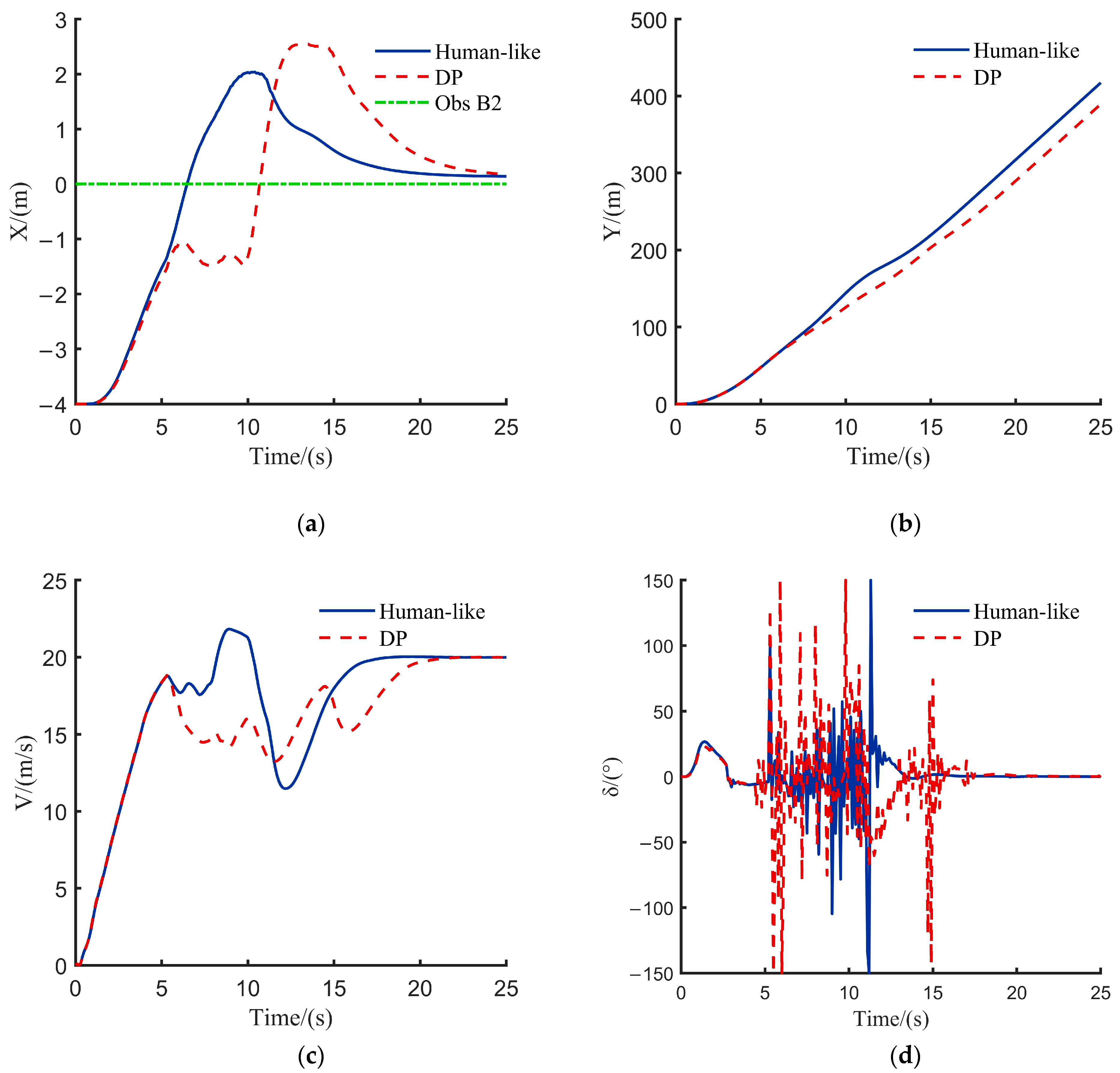

Scenario Three

In the scenario depicted in

Figure 10, both decision planning methods successfully completed the three-stage lane change process: vehicle start, lane change for overtaking, and return to the original lane. The target vehicle A engaged in a game-theoretic interaction with the rear vehicle B2 in the target lane. The following figure compares the distinct driving parameters under the two decision planning methods. Scenario 3 Comparison of vehicle driving parameters under different decision-making methods is illustrated in

Figure 11.

Simulation results highlight the divergence in decision-making intelligence between the two models. The dynamic programming model’s hesitation and instability during overtaking reveal its cost function’s inability to account for interactive behaviors. In contrast, this anthropomorphic model allows vehicles to proactively evaluate the long-term benefits of different behaviors by incorporating game theory and reward weighting. For aggressive driving styles, its cost function prioritizes efficiency, leading the model to generate and execute more decisive overtaking trajectories, with average lane-change speeds increasing by 7.06%. This demonstrates that the model’s performance advantage arises not from more complex trajectory planning, but from its advanced, human-like decision-making intelligence.

4.3. Simulation Results Verification and Discussion

To confirm that the observed performance improvements—such as a 7.06% increase in average speed and a 75.8% improvement in stability—were statistically significant, we conducted independent samples

t-tests [

31]. For each of the two driving scenarios involving game-based lane changes, we performed 10 independent simulation runs to gather distribution data for the performance metrics. The mean values from 10 independent simulation experiments are shown in the

Table 7.

Experimental results show that, compared to traditional dynamic programming (DP) methods, the human-like model proposed in this paper strikes a superior balance between lane-changing efficiency and smoothness. The average lane-changing speed increased by approximately 5.6%, highlighting the model’s advantage in efficiency. Additionally, the mean rate of change in the steering angle decreased by 75.1%, demonstrating improved maneuver smoothness and driving stability during lane changes. The comprehensive results demonstrate that the proposed algorithm achieves statistically significant improvements in lane-changing efficiency and smoothness, validating the effectiveness and reliability of this method.

Unlike previous studies on lane-changing strategies that focused primarily on trajectory planning optimization [

32,

33], this research introduces an integrated model that combines driving style characteristics, game theory, and a dynamic reference line-switching mechanism. By analyzing driver behavior and incorporating a multi-agent decision-making process, the framework enables multi-objective co-optimization of safety, comfort, and traffic efficiency in complex scenarios. The model’s effectiveness has been validated in simulation environments. However, its parameters are highly dependent on typical driving scenarios, and its adaptability to extreme or uncertain traffic conditions requires further validation through real-world testing.

5. Conclusions

To address the limitations of ‘mechanical’ lane changes in intelligent driving, this paper proposes a human-like decision-making strategy that integrates driving style with game theory. By modeling interacting vehicles as agents, this strategy achieves ‘closed-loop’ interaction, with its core capability being the generation of differentiated anthropomorphic behaviors. This marks a paradigm shift from ‘trajectory optimization’ to ‘behavioral intelligence,’ unlocking significant application potential in personalized ADAS, high-fidelity simulation testing, and connected cooperative driving. It provides a key solution for seamlessly integrating autonomous driving into human traffic ecosystems.

However, this study has several limitations. First, the current model’s classification of driving styles is based on offline data, which makes it difficult to respond in real time to changes in the driver’s state. Additionally, it lacks systematic sensitivity testing and confidence interval analysis to accurately assess the stability of model outputs in response to perturbations in input parameters. Future research will focus on two key areas: first, developing open online driving style recognition technology to enable strategies that can dynamically adapt to real-time changes in driver states; second, conducting large-scale robustness testing and creating dynamically adaptive weighting strategies to improve the adaptability and safety of these strategies in complex traffic environments.