1. Introduction

Since the initiation of China’s “863 Program” in 2001, which focused on electric vehicles, the country has embarked on more than two decades of NEV R&D, evolving from being a technological follower to being a global leader. In 2023, China’s NEV sales reached 9.49 million units, representing more than 60% of global sales (approximately 15 million units), significantly exceeding sales in Europe (approximately 3 million) and the United States (approximately 1.4 million). In 2023, the NEV penetration rate in China surpassed 35%, outpacing that in the European Union (approximately 20%) and the United States (7%). Moreover, in 2023, China exported 1.77 million NEVs, representing a 67% year-on-year increase and establishing China as the world’s largest NEV exporter, with key markets in Southeast Asia, Europe, and Latin America. These achievements raise a critical question: what explains the rapid rise of China’s NEV industry? This study investigates this question through the lens of patent innovation.

As core embodiments of technological innovation, patents offer valuable insights into industrial dynamics, making patent data analysis a crucial methodology in NEV research. However, the vast volume of patents, coupled with complex technical descriptions and specialized terminology, poses significant challenges to traditional classification methods in terms of both efficiency and accuracy [

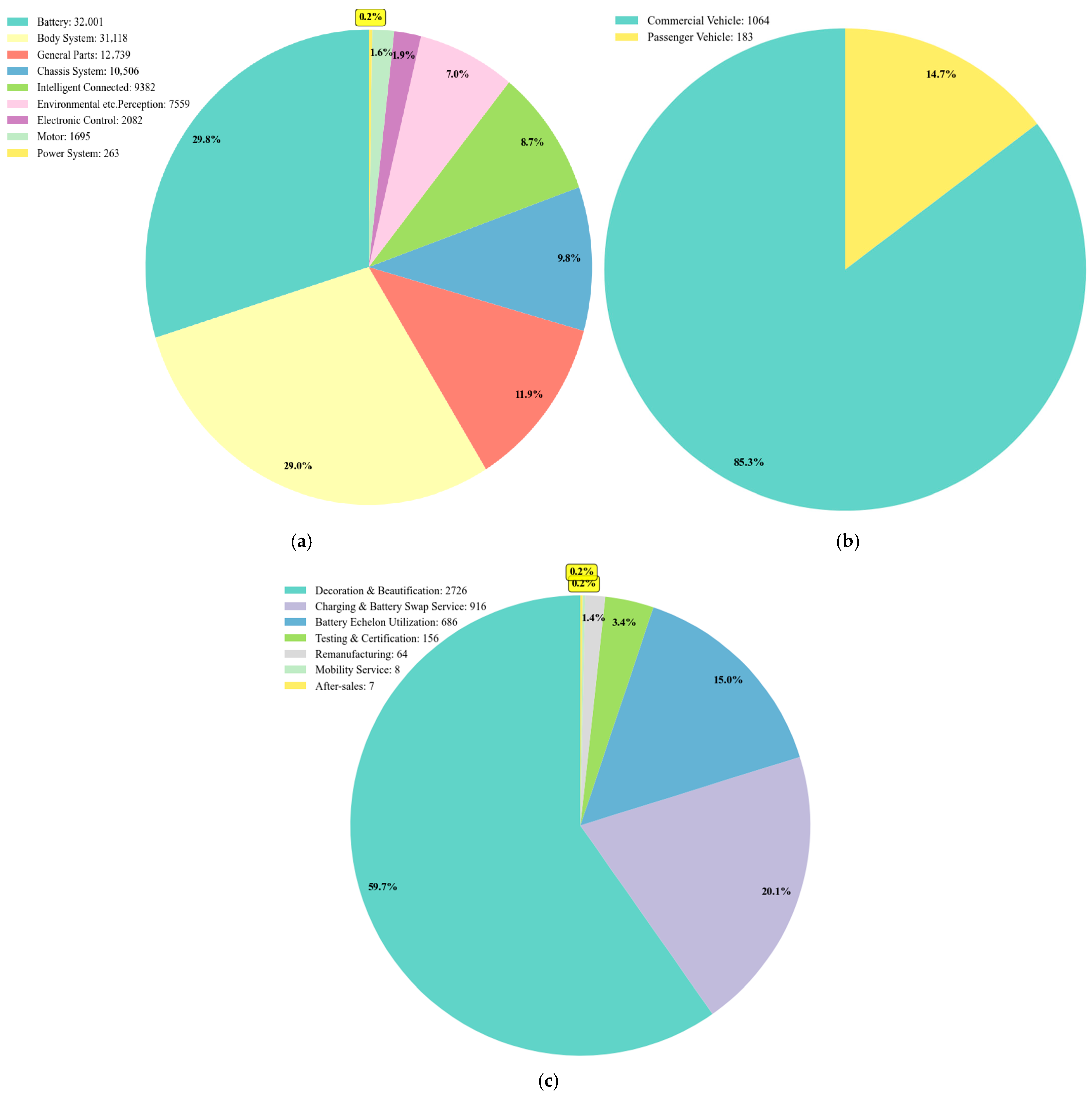

1]. Furthermore, the NEV industry encompasses multiple layers of the industrial chain: upstream components, midstream complete vehicles, and downstream aftermarket services. For instance, the upstream component layer includes batteries, motors, electronic controls, intelligent connected systems, body systems, power systems, chassis systems, universal components, and environmental perception systems, among others. The battery subcategory alone contains further subdivisions, such as battery packs, cells, battery structural components, and battery management systems. Constructing a precise and hierarchically structured classification framework for such a complex and multilayered industry remains a challenge. Although pretrained language models such as BERT have improved in the area of general patent classification, their performance in the specialized NEV domain is still limited, and the risk of model hallucinations remains a significant concern [

2,

3,

4,

5].

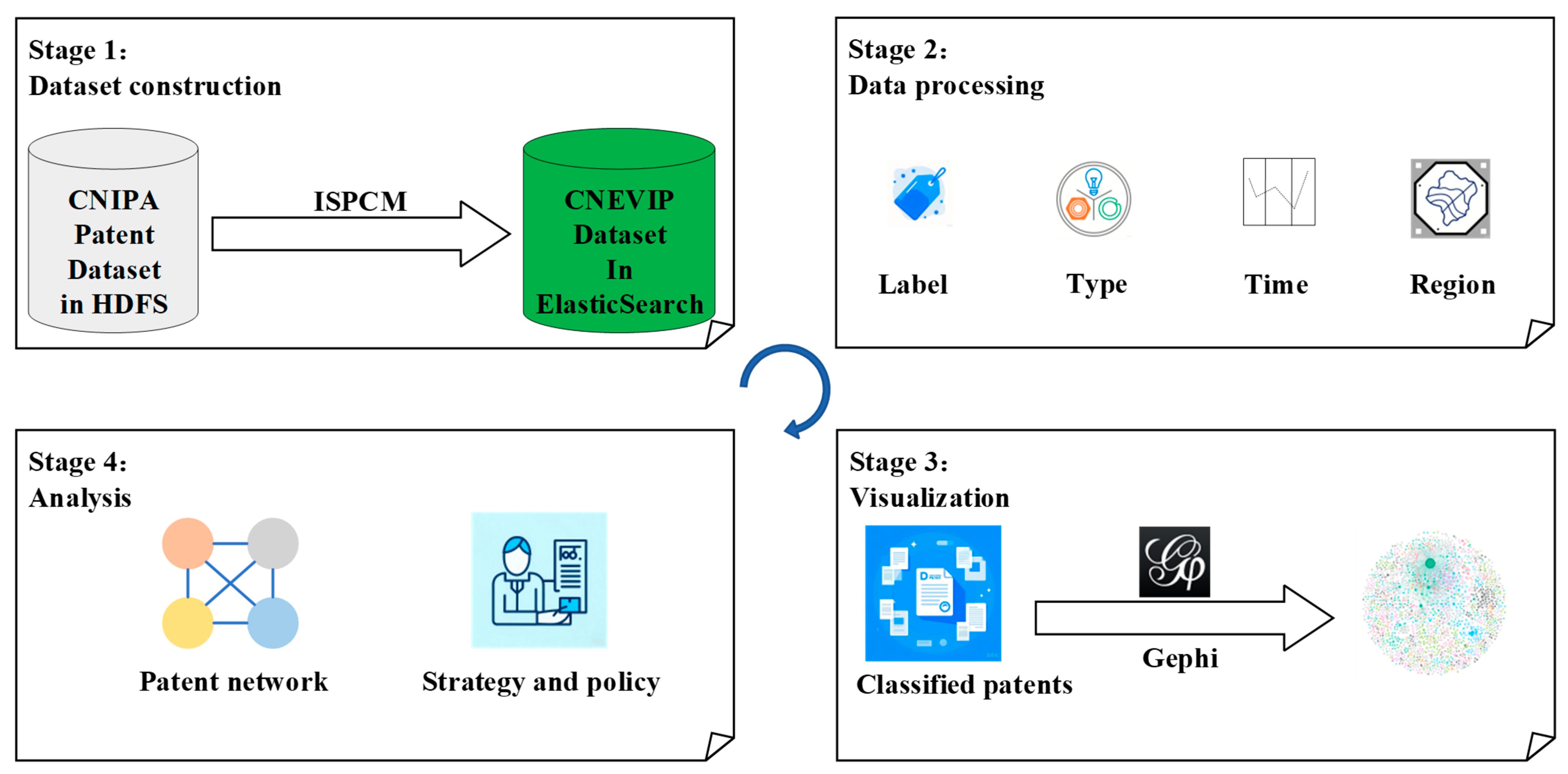

To overcome these challenges, this study introduces an industry-specific patent classification methodology (ISPCM) that integrates expert knowledge with large language models (LLMs). Specifically, we first construct a multilayer classification system—an NEV industry knowledge graph—and design rule-based matching patterns to identify patents across industry segments. These patterns are incorporated into LLM prompts. This approach becomes further enhanced by the reasoning and question-answering capabilities of LLMs, improving classification efficiency while reducing the risk of hallucinations.

In parallel, complex network theory provides powerful tools for analyzing relationships and dynamics in large-scale systems [

6,

7]. We combine this framework with the ISPCM to examine the evolution of China’s NEV patent collaboration network across temporal, industrial, and spatial dimensions, uncovering the mechanisms underlying the country’s global leadership [

8].

Overall, this study contributes to the field by enhancing the accuracy of NEV patent identification [

9,

10,

11], revealing the structural features of patent collaboration, and diagnosing any potential risks within the innovation network [

12]. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews the related literature;

Section 3 outlines the research framework;

Section 4 presents the results and discussion; and

Section 5 concludes with implications and future research directions.

2. Literature Review

In recent years, technology identification and patent analysis in the NEV industry have attracted significant attention in both academic and industrial circles. Existing studies have explored various perspectives, including technological trajectories, cooperation networks, and evolutionary dynamics [

13,

14].

Yuan et al. [

13] reported a gradual recovery in fuel cell electric vehicle (FCEV) technologies that has been occurring since 2014. The United States, Japan, Germany, China, and South Korea remain core contributors, although the sources of FCEV innovation are undergoing restructuring. Leading firms, particularly major automakers and component suppliers, play pivotal roles in advancing hydrogen fuel cell technologies. Liu et al. [

14] reported that electric vehicle charging technologies are concentrated in areas such as line arrangement, batteries, safety devices, and charging stations. However, large institutions exhibit weak collaborations, and competition is focused on traction power, line arrangement, system control, and charging stations.

Complex network theory has proven highly effective for analyzing international cooperation patterns and synergistic effects, which often occur through the construction of multidimensional patent collaboration networks [

15,

16,

17]. For example, Wang et al. [

18] employed latent Dirichlet allocation and patent cooperation data to construct innovation networks, identify development periods, and reveal the evolution of hotspots such as batteries, drive systems, and control technologies. Li et al. [

19] examined patent networks in the Yangtze River Delta at the national and regional levels, highlighting distinct cooperation patterns across regions. Hu et al. [

20] applied social network analysis to reveal the core–periphery structure and regional disparities in China’s charging station patent collaborations. Chen et al. [

21] integrated the S-curve model using social network analysis and time series methods and identified the development phases for electric vehicle (EV) technologies and sustainable directions. Their findings suggest that EV technologies have reached saturation both globally and in South Korea, with South Korea maintaining a two-year advantage in areas such as fast charging, infrastructure, battery monitoring, and AI-based applications. Li et al. [

22] argued that China’s NEV industry is likely to evolve toward electrification, intelligence, lighter weights, and sustainability. However, their study was limited by overly generalized predictions, and it may lack actionable insights for national or corporate technology roadmaps.

In summary, while existing research has made significant progress in analyzing the new energy vehicle innovation network using patent data, it still suffers from two core limitations.

First, at the data level, a heavy reliance on IPC codes or keyword searches for patent identification leads to insufficient accuracy in cross-disciplinary fields such as NEVs, making it difficult to support fine-grained industrial chain analysis.

Second, from an analytical perspective, most studies either focus on macrolevel trend descriptions or are confined to static analyses of network topology, lacking an integrated framework that combines temporal evolution, the industrial chain structure, and the dynamics of collaboration networks.

This study aims to address these challenges by introducing the ISPCM to construct a more accurate CNEVIP dataset. Building on this foundation, we systematically characterize the evolutionary trajectory and structural mechanisms of China’s NEV patent collaboration network across temporal, industrial, and actor dimensions, providing new analytical perspectives and empirical evidence for understanding China’s rapid rise in this field. We highlight how our study, which focuses on the structural collaboration network, provides a complementary perspective to technology-focused approaches (e.g., energy scheduling in smart grids [

23] and IoT perception [

24]). Doing so enriches the overall understanding of the NEV innovation ecosystem.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study introduces the ISPCM for China’s NEV sector, integrating expert knowledge with LLMs to enhance the accuracy and relevance of patent screening. Applying this method, we systematically identified and analyzed NEV patents filed between 2001 and 2022, constructing for the first time a comprehensive patent collaboration network that examines temporal evolution, the industrial chain structure, and applicant nationality. The analysis provides novel insights into the structural mechanisms driving China’s global leadership in NEVs, offering significant theoretical contributions to innovation ecosystem research and substantive policy implications for sustainable industrial development. The key findings are as follows:

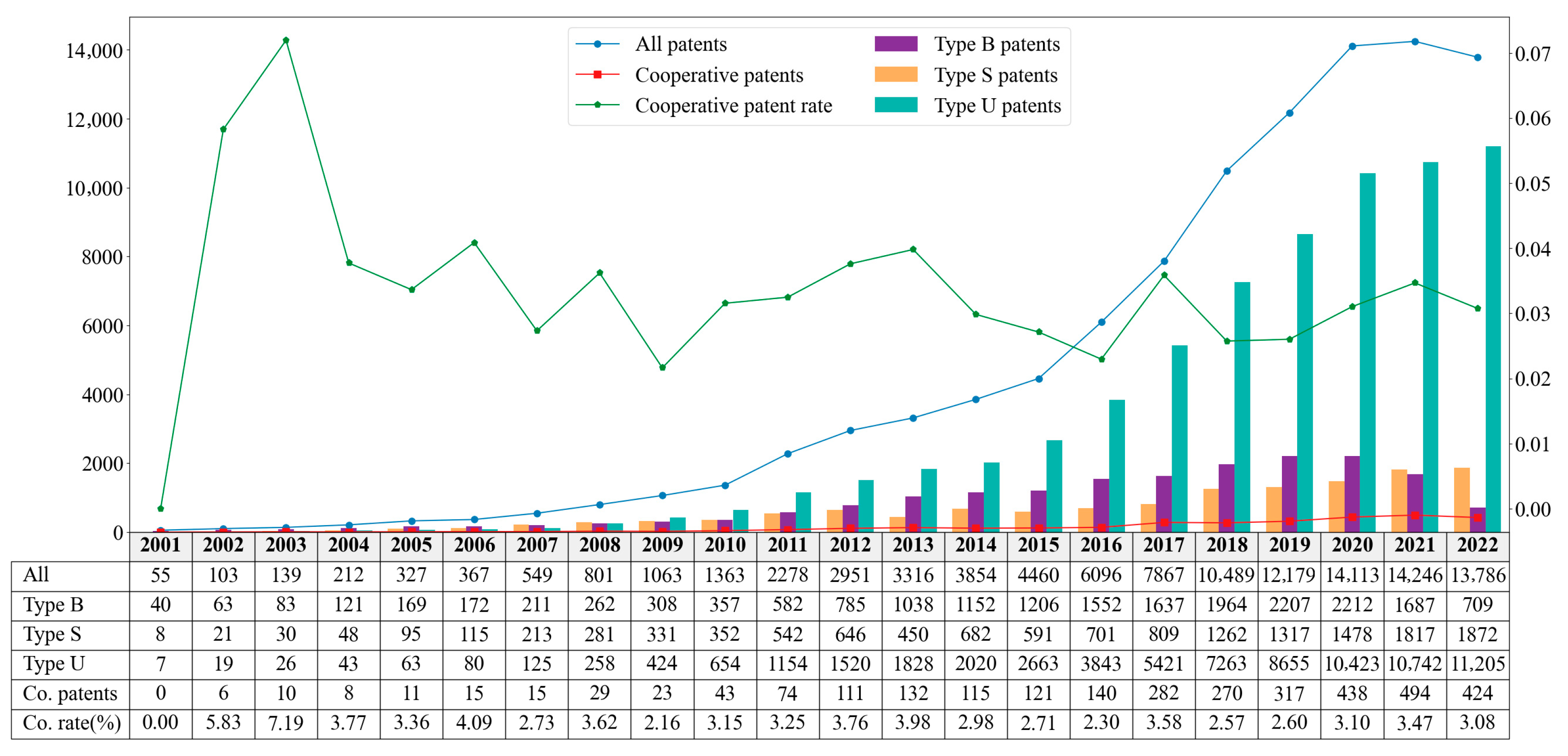

NEV patent filings in China have grown rapidly and continuously, evolving through three stages: initial development (2001–2008), accelerated growth (2009–2017), and maturity (2018–2022). Policy initiatives, such as the “Ten Cities, Thousand Vehicles” program, were implemented alongside market expansion during the observed period. The observed correlations could be influenced by other co-evolving factors, such as technological maturation and market development. Analysis of patent filings reveals that domestic applicants dominate throughout, with invention patents being more prevalent during the technology accumulation phase, while utility model patents become more common during the subsequent industrialization stage. This pattern in patent types is consistent with a transition from foundational R&D toward more application-oriented, iterative innovation.

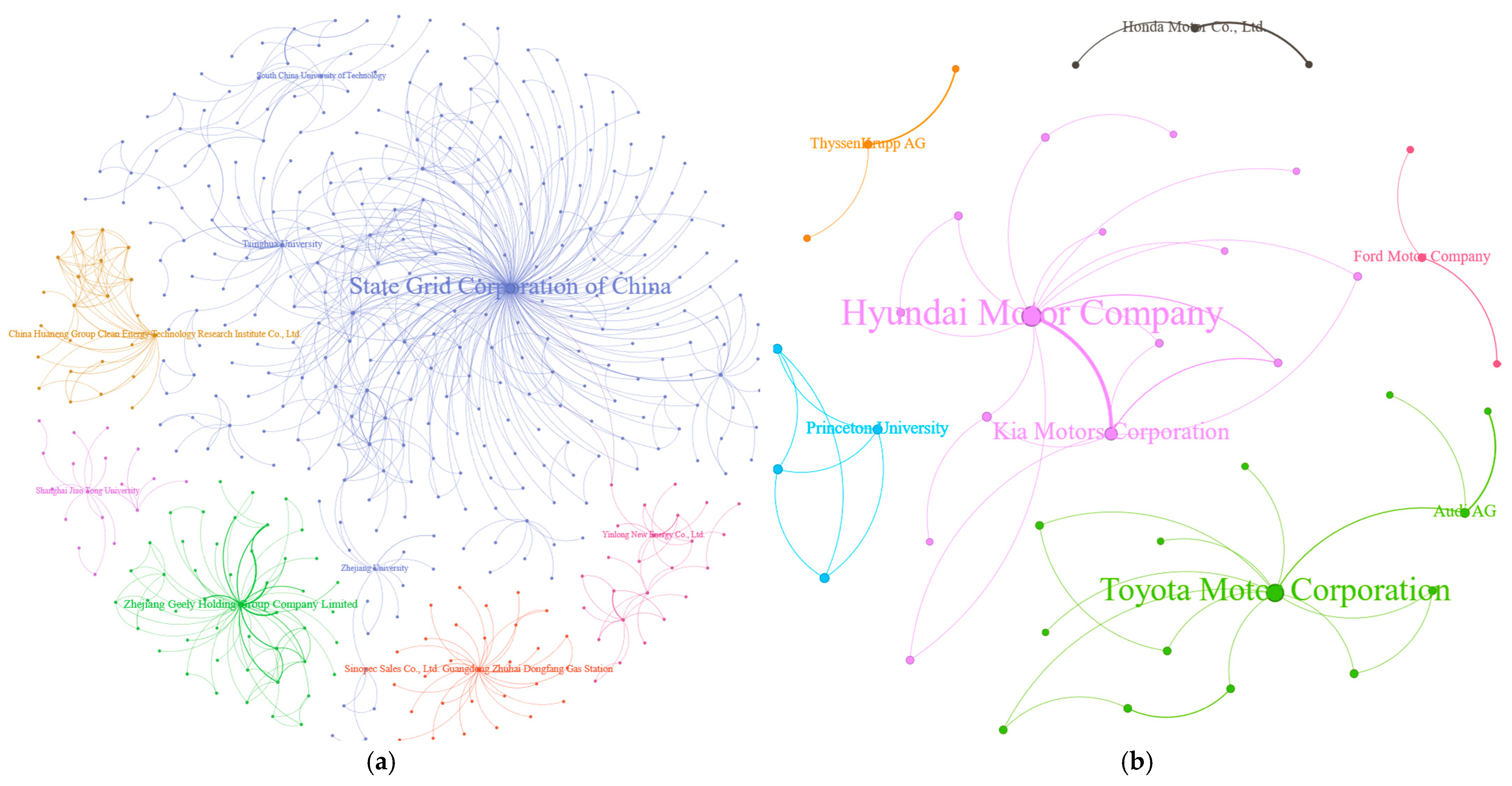

The collaboration network is large yet sparse, exhibiting a heavy-tailed characteristic. A “one-super, many-strong” oligopolistic structure is predominant, with the SGCC serving as the core hub. State-owned capital orchestrates infrastructure development, such as charging networks, and integrates industry–academia–research resources to serve as the central innovation coordinator. This finding highlights the decisive role of state strategy, complemented by market-driven private sector R&D, in shaping the innovation landscape.

During its initial development (2001–2008), collaboration was sparse and led by universities and foreign firms (e.g., Toyota). This was followed by rapid growth (2009–2017): During this period, state-owned enterprises (e.g., SGCC) reshaped the network into a core–periphery structure through policy leverage and infrastructure dominance. Maturity was reached (2018–2022): In this period, the core continued to consolidate, absorbing key academic clusters, while private firms (e.g., CATL) emerged as major technology contributors. This resulted in a dual innovation model in which SOEs coordinate the ecosystem and private firms drive specialized technological advancement.

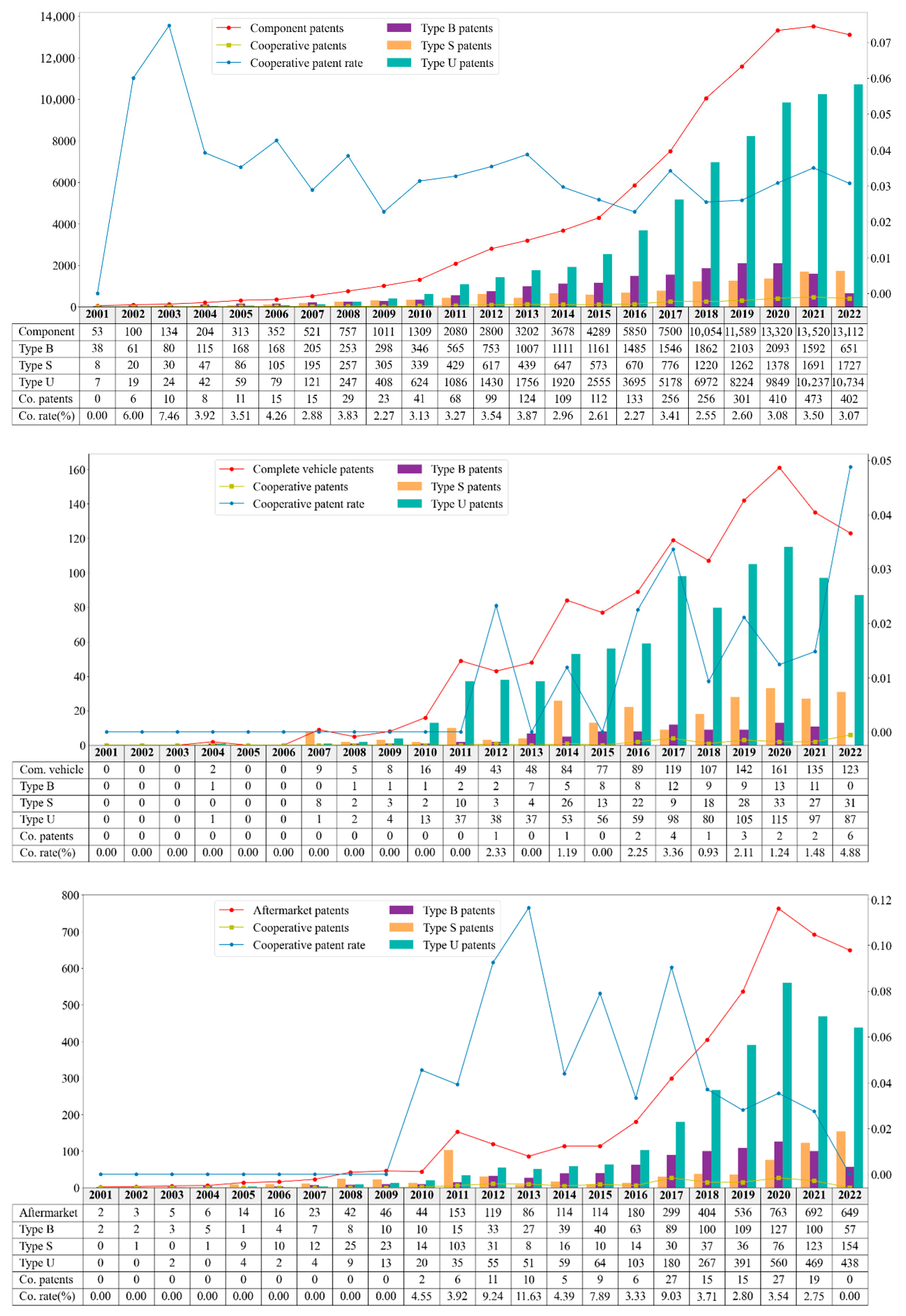

In terms of the divergent innovation patterns across the industrial chain segments, the component segment exhibits a dual structure that combines state-led collaboration and market-driven R&D. The complete vehicle segment persists as a tightly knit “exclusive club,” a structure defined by limited collaboration and intense internal competition. The aftermarket segment (e.g., battery recycling and reuse) forms specialized innovation clusters that are led by firms such as Brunp Recycling and GEM. Notably, the influence of the SGCC does not extend deeply into vehicle manufacturing, thereby revealing challenges in achieving full value chain integration.

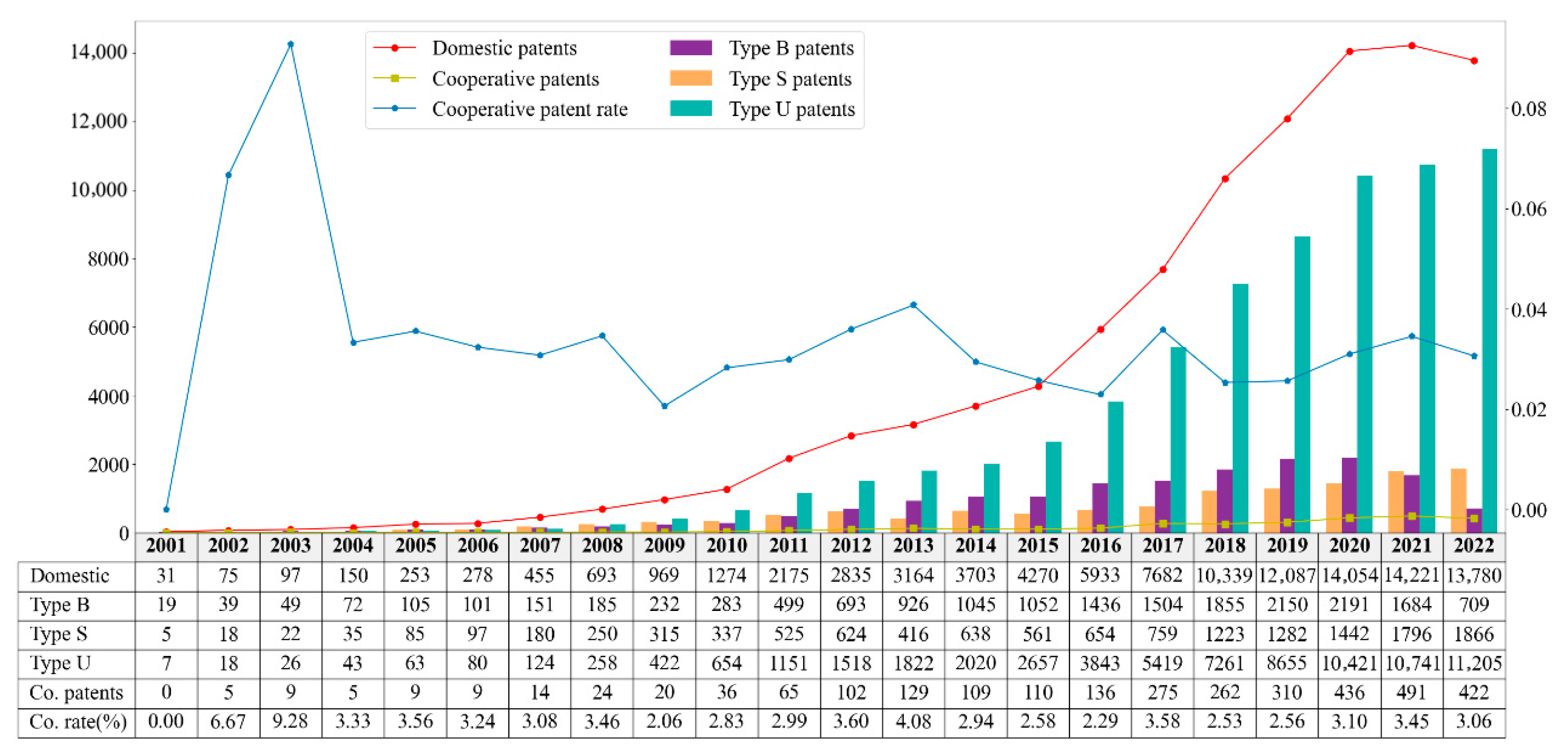

Domestic and foreign applicants operate largely in parallel, with domestic networks forming a policy-shaped mega-ecosystem with quantitative dominance and foreign networks forming exclusive “elite clubs” focused on high-value invention patents. The number of cross-ecosystem ties is minimal (with only 24 collaborative links), which indicates limited deep technological exchange and a potential decoupling risk. This study relies exclusively on patent data from the CNIPA. Consequently, our analysis does not capture cross-border collaborations that resulted only in patent filings in other jurisdictions (e.g., EPO, USPTO, WIPO). This may introduce a ‘home jurisdiction bias’, indicating that our findings regarding international ‘decoupling’ are primarily reflective of the collaboration dynamics within the Chinese domestic innovation system. Future research incorporating international patent families would provide a more global perspective.

In summary, China’s NEV leadership stems not from isolated technological breakthroughs but from a state-orchestrated, market-supported dual-circulation model that enables rapid scaling, efficient resource integration, and iterative application development. However, challenges remain in terms of original innovation, cross-chain coordination, and international collaboration.

On the basis of this study’s findings and limitations, we suggest several promising research directions:

The three-phase evolution model proposed in this study is primarily based on the observation of time series macrolevel network metrics (e.g., number of nodes and number of links). While the model is heuristic, future research could validate and refine this model by employing more granular dynamic network analysis methods, such as introducing overlapping time windows and calculating community persistence indices. Future studies could also employ temporal network analysis or exponential random graph models to better capture the dynamics of collaboration formation and network evolution.

The causal mechanisms between network position (e.g., centrality) and innovation outcomes (e.g., patent quality and product commercialization) remain underexplored. Panel data regression or case-based longitudinal analysis could offer deeper insights in this area.

Extending the network analysis to include major NEV markets such as the U.S., Germany, and Japan would enable comparative studies of innovation structures, core players, and policy impacts, thereby helping to identify the competitive advantages and strategic reference points.

The incorporation of R&D investment, government subsidies, talent mobility, and market data could lead to the development of a more comprehensive analytical framework. For example, how do subsidies affect network connectivity? Does university talent cultivation increase corporate innovation?

Beyond classification, future research could apply natural language processing to enable the semantic mining of patent texts, such as the identification of emerging technical themes, the tracing of technology trajectories, and the detection of innovation gaps, and integrate these insights into a network analysis to improve strategic forecasting.

While these research directions cannot advance the theoretical understanding of innovation networks, they can provide actionable insights for policymakers and corporate strategists aiming to enhance ecosystem collaboration, guide technology planning, and foster international cooperation within the global NEV industry.