Abstract

Path navigation for mobile robots critically determines the operational efficiency of warehouse logistics systems. However, the current QR (Quick Response) code path navigation for warehouses suffers from low operational efficiency and poor dynamic adaptability in complex dynamic environments. This paper introduces a deep reinforcement learning and hybrid-algorithm SLAM (Simultaneous Localization and Mapping) path navigation method for Mecanum-wheeled robots, validated with an emphasis on dynamic adaptability and real-time performance. Based on the Gazebo warehouse simulation environment, the TD3 (Twin Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient) path planning method was established for offline training. Then, the Astar-Time Elastic Band (TEB) hybrid path planning algorithm was used to conduct experimental verification in static and dynamic real-world scenarios. Finally, experiments show that the TD3-based path planning for mobile robots makes effective decisions during offline training in the simulation environment, while Astar-TEB accurately completes path planning and navigates around both static and dynamic obstacles in real-world scenarios. Therefore, this verifies the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed SLAM path navigation for Mecanum-wheeled mobile robots on a miniature warehouse platform.

1. Introduction

As e-commerce grows at a fast pace, the warehousing and logistics sector is confronted with twofold challenges: the surge in orders and the increase in operational complexity [1]. However, the traditional manual handling mode is inefficient and error-prone, hindering the achievement of modern warehousing and logistics’ high efficiency demands. In contrast, mobile robots can maintain high efficiency over a long period, which not only saves labor costs but also significantly improves the accuracy rate. Thus, they have become staples in smart factories, manufacturing hubs, and warehouses for goods handling [2]. As the core technology of mobile robots, path navigation includes environment perception, autonomous positioning, and path planning [3].

Within the domains of environment perception and autonomous positioning, the Quick Response (QR) code path navigation [4] is widely used in warehousing scenarios due to its relatively simple deployment and controllable cost. However, modernized warehousing environments face challenges such as high-frequency personnel movement, goods temporarily blocking the aisles, and dynamically changing operating aisles, making the operating environment complex and variable. Because traditional QR code navigation lacks effective real-time perception, it struggles to adjust paths flexibly in dynamic scenarios, reducing system efficiency. In contrast, laser SLAM (Simultaneous Localization and Mapping) boasts simple equipment requirements, broad applicability, and exceptional positioning precision [5]. It breaks through the dependence of QR code navigation on preset physical markers, enabling mobile robots to autonomously perceive complex dynamic environments. This allows for accurate map construction and simultaneous self-localization in unknown environments [6], thus adapting to complex warehouses and facilitating collision-free, efficient path planning.

In warehouse settings, path planning for mobile robots stands as a core technology enabling autonomous navigation during logistics operations [7]. The majority of traditional path-planning studies are categorized under algebraic, optimization, and AI approaches [8] and have been widely applied to warehouse robot path planning. These methods primarily rely on sensors to perceive the surrounding environment, determine the robot’s position and orientation, and employ planning algorithms to compute the optimal path from start to end. In essence, algebraic strategies employ algebraic equations to tackle exhaustive path planning issues [9], whereas optimization strategies generally resort to heuristic algorithms to optimize the robot’s route [10]. This includes intelligent planning algorithms like the Swarm algorithm [11], the ant colony method [12], and the genetic approach [13], along with the search-centric Astar algorithm [14]. However, these methods generally rely on static, known environments with certain limitations in practical applications. Hybrid algorithms can combine the strengths of multiple algorithms, making them suitable for dynamic environments. Wang et al. proposed a hybrid approach combining an improved Astar algorithm and an optimized Dynamic Window Approach (DWA), enhancing global path optimization efficiency and obstacle avoidance capabilities. It demonstrates improved stability and reliability when traversing both static and dynamic obstacles [15]. Zhang et al. proposed a hybrid algorithm of the Modified Golden Jackal Optimization (MGJO) and the Improved Dynamic Window Approach (IDWA). The problem of being stuck in local optima during global path planning has been resolved, as validated in feasibility experiments [16]. Compared to previous methods, this paper proposes a hybrid path planning algorithm combining Astar and Time Elastic Band (TEB), the feasibility of which has been validated in a warehouse micro-platform.

Lately, Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) rooted in AI has found extensive use in robot path planning [17]. Given the complex and dynamic characteristics of warehouse environments, a single path planning algorithm struggles to meet the demands for efficiency and precision in operational processes [18]. DRL is incorporated into mobile robot path navigation, with no need to depend on data or models. Instead, it gathers its own state and environmental data through sensors, and following algorithmic computation, selects the next action based on the reward size. During this process, the system keeps learning and optimizes strategies to pursue the highest reward [19], thereby achieving stable and efficient path planning. Meanwhile, DRL is capable of handling robot path planning tasks with dynamic changes, along with efficiently processing high-dimensional environmental information [20]. Abdalmanan et al. used Deep Q Network (DQN) navigation in open environments to avoid collisions and complete path planning [21]. Since DQN cannot handle continuous action control, Shripad V et al. built upon this foundation and adopted the Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG). Solving decision problems under uncertainty and dynamics in a two-dimensional environment has improved the success rate of reaching targets [22]. Choi et al. proposed a hierarchical DRL architecture that mainly uses the Soft Actor–Critic (SAC) algorithm for path planning in both static and dynamic surroundings. An integrated path planner was used to improve performance [23]. Fujimoto et al. proposed Twin Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (TD3), which introduces a twin Q-network and a delayed update strategy [24]. It enables handling of continuous control tasks and resolves the Q-value overestimation issue in DDPG. Additionally, compared to SAC, the TD3 lightweight design enables higher computational efficiency, allowing it to rapidly converge to high-precision control strategies [25].

Despite extensive research in navigation path planning, most existing studies focus on simple heuristic algorithms applied to two-dimensional maps. These approaches suffer from oversimplifying real-world warehouse environments and poor dynamic adaptability. While a few have proposed DRL for path navigation, they lack effective experimental validation in warehouse settings.

This paper aims to bridge these gaps by making the following key contributions:

(1) A Gazebo-based 3D warehouse environment for the TD3-based path planning algorithm is established. The offline training results confirm that TD3 applies to deep reinforcement learning-based path planning for mobile robots in logistics and warehousing environments.

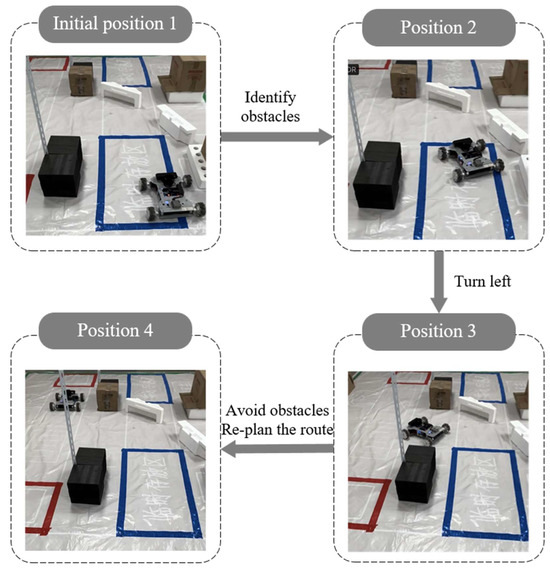

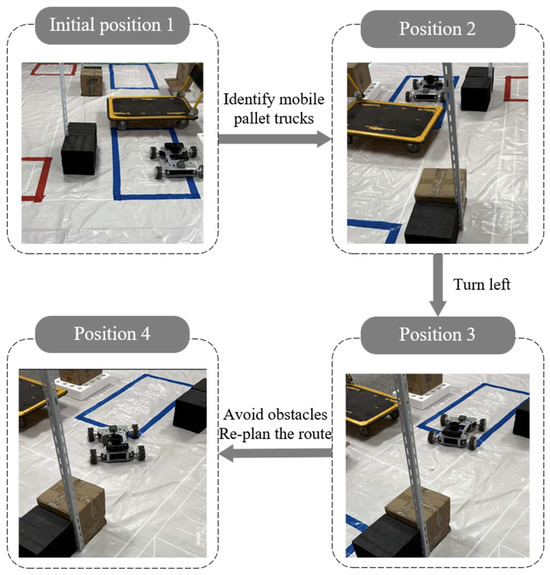

(2) A Mecanum-wheeled mobile robot platform was developed to experimentally validate the feasibility of the hybrid Astra-TEB path planning approach in real-world scenarios. Experiments confirm that robots can achieve efficient obstacle avoidance in both static and dynamic environments.

2. Mecanum-Wheeled Robot and Warehouse Environment

2.1. Modeling for Mecanum-Wheeled Robots Based on SLAM

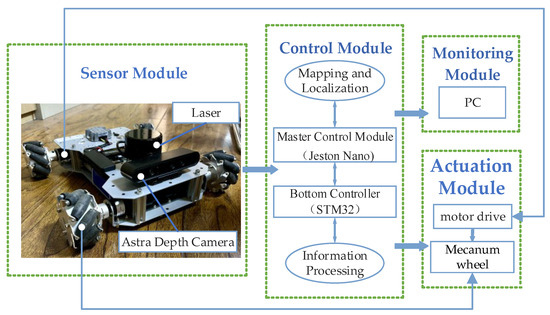

Figure 1 shows the integral module for the SLAM mobile robot, which includes a control module, a sensor module, an actuation module, and a monitoring module. Among them, the sensor module consists of LiDAR, a binocular camera, an IMU, an odometer, etc., gathering data on both the environment and the autonomous robot. The control module is tasked with processing and computing sensor data, which consists of the main control module (Jeston Nano) and the underlying controller (STM32). The bottom controller first receives and fuses the sensor information and then transmits the processed data to the master control module, which utilizes SLAM to realize the positioning and map construction of the robot. The actuator module drives the robot according to the instructions of the control module. The monitoring module monitors the real-time data and movement of the mobile robot using a PC.

Figure 1.

Integral module for mobile robot.

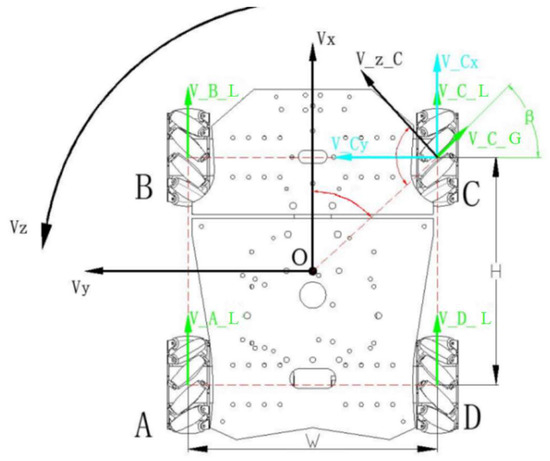

Among them, the wheel part of the SLAM robot is modeled as a Mecanum wheel. The Mecanum wheel is equipped with three degrees of freedom, including rotation around the wheel axis, movement in the direction of the roller axis, and rotation about the wheel–ground contact point [26]. The Mecanum wheel is based on the chiral symmetry of the left-rotating and right-rotating wheels, which not only increases the stability of the mechanism but also improves the load capacity while increasing the control convenience. Figure 2 shows the Mecanum-wheeled robot’s kinematic structure.

Figure 2.

Kinematic modeling of a mobile robot based on the Mecanum wheel.

The relationship between the translational velocities , of the C-wheel centroid and the overall velocities , , is as follows:

where represents the wheelbase between the left and right Mecanum wheels; H represents the wheelbase between the front and rear Mecanum wheels; and are the x and y axis translational velocities; is the speed of rotation of the robot around the z axis; and denotes the angle between the wheel’s center of mass and the line from the origin.

The moving velocities , of the C-wheel’s center of mass are related to the wheel velocity and the roller linear velocity as follows:

where denotes the angle between the wheel axis and the roller axis.

Therefore, the C-wheel roller line velocity is as follows:

Based on Equations (3) and (6), define .

Given that , the velocity of the C-wheel is calculated as follows:

A-wheel, B-wheel, and D-wheel center of mass velocities are related to roller linear velocities as follows:

Finally, based on Equation (7), we solve the overall velocities as follows:

Derived from the above formula, the Mecanum-wheeled robot’s kinematic model yields its overall velocities in x, y, and z directions and four wheel speeds.

2.2. Gazebo-Based Warehouse Environment Construction

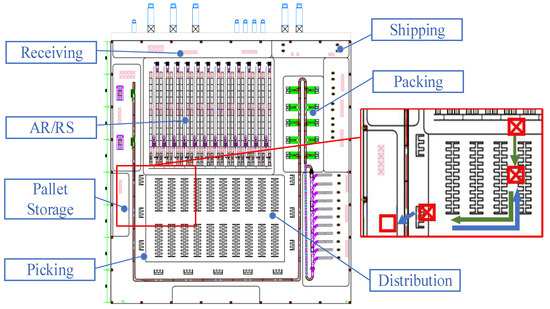

The construction of the warehouse simulation environment is based on the floor plan of an intelligent warehouse, as shown in Figure 3. It includes seven areas: receiving area, AR/RS warehouse area, distribution area, picking area, pallet storage area, packing area, and shipping area. The basic workflow is as follows:

Figure 3.

CAD intelligent warehouse floor plan.

- (1)

- Preparation for goods receipt: Palletized-unit goods are first unloaded to the receiving area in preparation for warehousing. After operations including quantity counting, inspection, label printing, and system entry are completed, forklifts transport the goods to the entrance of the AR/RS warehouse area for storage.

- (2)

- Order processing: Based on order requirements, goods are retrieved from the AR/RS warehouse area. AGVs then transport the goods to the distribution area for buffering, after which they are sent to the picking area for order picking operations.

- (3)

- Pallet handling: Empty pallets are conveyed to the pallet storage area, while nonempty pallets are returned to the distribution area shelf for storage.

- (4)

- Goods sorting and distribution: The picked goods are transferred via conveyor belts to the packing area for packaging and subsequently loaded onto trucks in the shipping area for distribution.

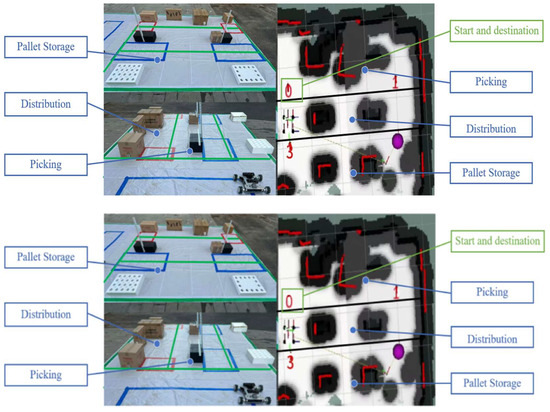

Aiming at the function of the robot in the distribution area, design a warehouse environment simulation scenario. It picks up the goods from the distribution area and sends them to the picking area for picking, then sends the empty pallet to the pallet storage area, and the nonempty pallet is sent back to the distribution area for storage.

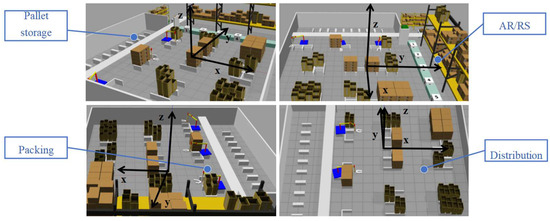

By the design of the aforementioned training scenarios, a 3D warehouse model is constructed using Gazebo 11, forming the platform basis for subsequent TD3-based mobile robot path planning training. The specific parameters for warehouse environment modeling in the Gazebo environment are presented in Table 1. The 3D training scenario is built in Gazebo simulation software, as shown in Figure 4.

Table 1.

Gazebo modeling parameters.

Figure 4.

Construction of the Gazebo Training Scenario.

3. TD3 Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Path Planning

3.1. DRL Problem Modeling

3.1.1. State Space

Mobile robots must gather environmental and their own positional information so that they can make optimal decisions after training with deep reinforcement learning algorithms. This information constitutes the “state space.” In this paper, the state space S for path planning encompasses two aspects: first, the positional relationship between the robot and obstacles, along with the distance from the robot to the destination; second, its own posture data and movement state [27].

where represents the distance of obstacles in n directions obtained by laser radar.

where represents the distance of the robot from the end point at time t; denotes the azimuth;, ) is the coordinate of the robot at time t; ) is the coordinate of the end point; and denotes the current yaw angle derived from the mobile robot’s IMU.

We employ the Boolean variable ‘done’ as a state variable: it is True if a collision occurs or the end is reached at the end of training, and False otherwise, as shown in Equation (18).

Therefore, the state space S of this paper is shown in Equation (19).

3.1.2. Action Space

Continuous movement results in a relatively smooth path for the robot, without frequent or abrupt starts and stops, matching operational traits of the real world. Therefore, the robot action space includes specific linear and angular speeds [28].

where and are the linear speed and rotational angular speed of the robot, respectively.

3.1.3. Reward Function

To obtain higher positive rewards for continuous movement and thereby facilitate forward exploration, the mobile robot is designed with a reward function. During normal operation, it should complete path planning smoothly and safely, with an immediate reward assigned per timestep. This formulation encourages rapid task completion through positive velocity reward v, penalizes aggressive turning through the negative angular velocity term |w|, and enforces obstacle avoidance through safety distance penalty .

where r3 represents the weight for penalizing the distance between the mobile robot and an obstacle, and represents the movement state reward.

where is a proximity reward function. It establishes the reward for each step according to the distance of the mobile robot to the destination.

where represents collision penalties and rewards for reaching end points.

where R represents the total reward. By using , , and a comprehensive reward function is constructed, encompassing three components: movement state reward, end-approaching reward, and end-reaching reward. This incentivizes the robot to seek higher reward values for optimal path exploration continuously.

3.2. TD3 Algorithm Design

The TD3 is an improved version of DDPG, which refines a structure comprising one Actor and two Critic Networks. Firstly, TD3 employs twin Critics to calculate the corresponding Q-value to actions and selects the network yielding the minimum Q-value, thereby addressing the Q-value overestimation issue inherent in DDPG [29]. Secondly, it incorporates delayed policy updates for the Actor, whereby the Critics updates multiple times until attaining a relatively stable state, after which the Actor performs an update to more precisely determine the max Q-value estimate. Finally, it introduces target policy smoothing by adding noise to allow TD3 to avoid over-fitting in the policy network [30]. Therefore, TD3 requires the construction of an Actor, which takes the environmental data as input and outputs the mobile robot actions, along with two Critics that take both the environmental state and actions from the Actor as inputs and output the Q (state, action).

In the intelligent warehouse environment, the TD3 algorithm uses the Actor to outputs a deterministic action for the current state S. To encourage exploration, exploration noise is added.

Use two target Critics and take the minimum Q-value.

where is the immediate reward, and (with ) is a discount factor determining the priority of long-term rewards.

In order to avoid frequent updates of the Actor leading to policy oscillations or unstable training, TD3 updates the Actor only after a certain number of Critic updates. Loss functions for the Critic and Actor are outlined below:

The Critic loss is trained to minimize the squared error between its predicted Q-value and the target Q-value y. Additionally, the Actor maximizes the ) for the actions it outputs.

Update the actor by the deterministic policy gradient to maximize expected return via gradient ascent.

where denotes a randomly sampled batch of states from the experience replay buffer, with batch size N; ) represents the gradient of the output of the first Critic network with respect to the action input ; and is the gradient of the output of the Actor network at state s with respect to its own parameters v.

The soft update coefficients are set by the soft update method to update the target network parameters in the direction of the current network parameters in small increments to avoid training oscillations due to parameter updates that are too fast.

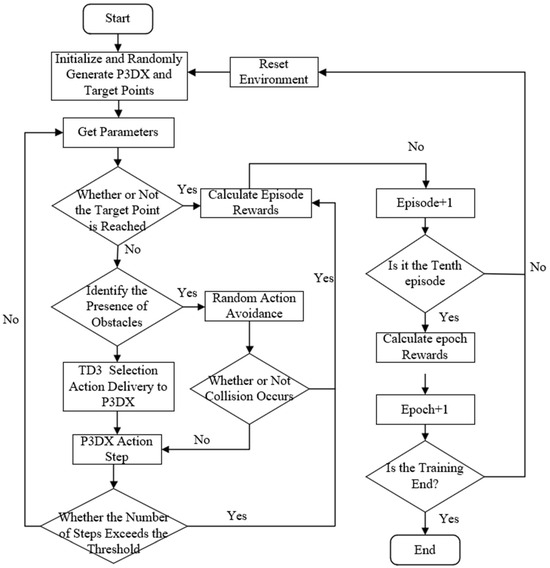

Building upon the above-described TD3 algorithm design, a process flow for the offline training of the TD3 path planning algorithm in an intelligent warehousing scenario is established, as shown in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: TD3 Path Planning Strategy |

| Initialize with random weights; ; ; random near obstacle triggers = true. for t = 1 to T do of size N from D to [−1, 1]; Select action: < 0.35 random near obstacle triggers=true = pre-generated random action(8-15steps) w = [−3.14, 3.14] rad/s random steps counter = random steps counter− 1 if t mod d = 0: Update actor by the deterministic policy gradient Update target networks end if end for |

3.3. TD3 Algorithm Training

3.3.1. Setup of Training Environment

The experiments were carried out using the following software: Ubuntu 20.04, Python 3.8.10, and PyTorch1.10. A computer with a Ryzen 7 5800H, 16 Gb RAM, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4050 graphics card with 6 GB GDDR6 graphics memory was used. The total training time is 16.5 h.

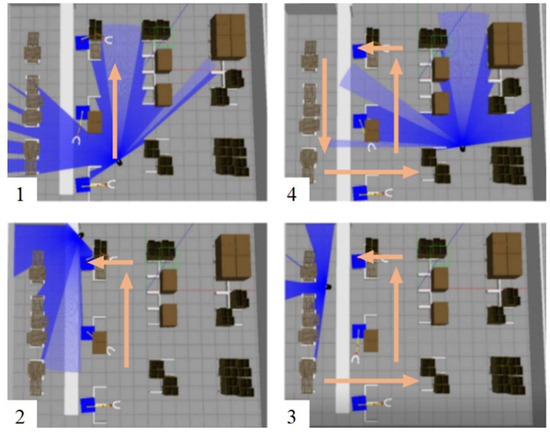

In the Gazebo simulation environment, a mobile robot is simulated using Pioneer P3DX, which is equipped with LiDAR sensors based on the principle of calculating the distance between objects according to the time-of-flight method. The laser data are transmitted to the TD3 network, and the output angular and linear velocities are used to control the movement of the P3DX, as shown in Figure 5. The P3DX picks up the goods from the distribution area and delivers them to the picking area. Additionally, the P3DX sends the empty pallets from the picking point to the pallet storage area, and the nonempty pallets are sent back to the storage point in the distribution area. Training parameters are configured as illustrated in Table 2.

Figure 5.

Gazebo simulation training scene.

Table 2.

Settings of parameters for the TD3 algorithm.

The TD3 training of P3DX is realized by setting up the training environment, starting the training cycle, single-step execution process, reward calculation, evaluation, and reset, and the training process is outlined in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Approximate training process of P3DX.

3.3.2. Training Results and Analysis

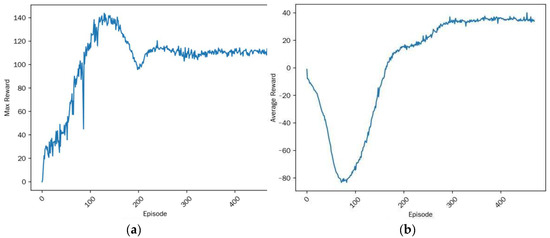

The TD3 algorithm underwent 480 training rounds in the Gazebo simulation environment, and the variation of max and average reward with training round counts is shown in Figure 7. Based on the training performance of the TD3 algorithm, the learning process can be divided into the following three distinct phases:

Figure 7.

TD3 reward value. (a) Max reward; (b) average reward.

In the first phase (Episodes 0–100), the maximum reward exhibits oscillatory behavior with a gradual upward trend, while the average reward declines to its lowest level. This indicates that the P3-DX is in an intensive exploration stage, frequently colliding with obstacles in the warehouse environment.

In the second phase (Episodes 100–250), the maximum reward experiences significant fluctuations after a peak value, reflecting the agent’s attempt to explore high-risk, high-reward maneuvers. Meanwhile, the average reward demonstrates a rapid increase, suggesting that the algorithm begins to identify potentially effective navigation policies and progressively improves its performance.

In the final phase (after Episode 250), both the maximum and average rewards stabilize at high values, indicating convergence of the TD3 algorithm. The agent has successfully learned a robust and efficient policy, enabling consistent and effective path planning within the intelligent warehouse environment.

5. Conclusions

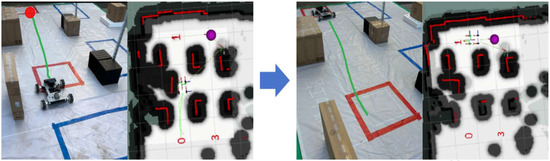

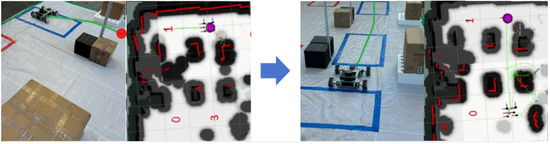

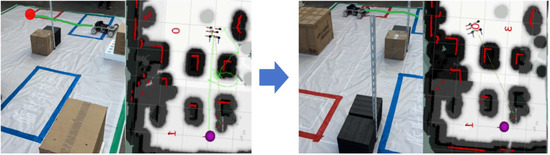

In pursuit of mobile robots’ dynamic adaptability and responsiveness in logistics warehousing settings, this paper explores and verifies a path planning strategy based on the TD3 and Astar-TEB hybrid algorithm. Key findings are elaborated below.

- (1)

- Based on the TD3 deep reinforcement learning path planning method, offline training and verification were performed via a Gazebo-simulated warehouse model. The simulation results indicate that mobile robots can make continuous, effective decisions and complete path planning tasks in warehouse environments.

- (2)

- A laser SLAM-equipped Mecanum-wheeled mobile robot based on the Astar-TEB hybrid algorithm. Experiments demonstrate the successful completion of path planning tasks and obstacle avoidance in both static and dynamic real-world scenarios.

In the future, the above TD3 deep reinforcement learning offline training results will be deployed to Mecanum-wheeled mobile robots for real-scenario vehicle verification. Next, modifications to the state space design and reward function will be made to accommodate platform-specific constraints and task requirements. Finally, for larger warehouse maps, the system can be extended to hybrid SLAM full-scale automated guided vehicles (AGVs) or autonomous mobile robots (AMRs), accounting for additional state space dimensions such as shelf height and lighting conditions. Such measures will allow the proposed path planning strategy to be effectively applied in actual logistics and warehousing scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Z.M. and N.Z.; methodology, B.L.G. and N.Z.; software, Y.Y.Y. and C.Z.M.; validation, Y.Y.Y. and Y.W.; formal analysis, Y.Y.Y.; investigation, Y.W. and W.Z.; resources, Y.W.; data curation, W.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y.Y. and C.Z.M.; writing—review and editing, Y.W. and Y.Y.Y.; visualization, B.L.G.; supervision, Y.W. and N.Z.; project administration, Y.W. and N.Z.; funding acquisition, Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 52202497; the State Key Laboratory of Intelligent Green Vehicle and Mobility under Project, grant number KFY2413; and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, grant numbers FRF-TP-24-019A and QNXM20250006.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Xiao, H. Application and Development of 5G Technology in Smart Logistics Industry. In Proceedings of the 2023 9th International Conference on Computer and Communications (ICCC), Chengdu, China, 8–11 December 2023; pp. 1329–1333. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Qi, L.; Luan, W.; Guo, X.; Ma, H. Load-In-Load-Out AGV Route Planning in Automatic Container Terminal. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 157081–157088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, X.; Yang, X.; Liu, H.; Li, J.; Wang, P. Path planning techniques for mobile robots: Review and prospect. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 227, 120254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, W.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y. Warehouse AGV Navigation Based on Multimodal Information Fusion. J. Acta Opt. Sin. 2024, 44, 0915003. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.; Yang, R.; Tan, B.; Xu, S.; Cen, M. A Fast 3D Laser SLAM Method for Indoor Scenarios. In Proceedings of the 2022 34th Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC), Hefei, China, 15–17 August 2022; pp. 2756–2761. [Google Scholar]

- Hashim, H.A. Guaranteed Performance Nonlinear Observer for Simultaneous Localization and Mapping. IEEE Control. Syst. Lett. 2021, 5, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.-M. Path Planning for Batch Picking of Warehousing and Logistics Robots Based on Modified A* Algorithm. Acad. J. Manuf. Eng. 2018, 16, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Daichuan, Y.; Weifeng, L.; Chenglin, W.; Baigen, C. A Novel Integrated Path Planning Algorithm for Warehouse AGVs. Chin. J. Electron. 2021, 30, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcó, A.; Hilario, L.; Montés, N.; Mora, M.C.; Nadal, E. A Path Planning Algorithm for a Dynamic Environment Based on Proper Generalized Decomposition. Mathematics 2020, 8, 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Liu, Y.; Zang, S.; Wang, L. Robot Path Planning Based on Genetic Algorithm Fused with Continuous Bezier Optimization. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2020, 2020, 9813040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, B.; Zhang, Y. Geometric parameter identification of industrial robots based on improved particle swarm algorithm. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 106331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akka, K.; Khaber, F. Mobile robot path planning using an improved ant colony optimization. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2018, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamini, C.; Benhlima, S.; Elbekri, A. Genetic Algorithm Based Approach for Autonomous Mobile Robot Path Planning. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 127, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.S.; Wang, B.; Xu, H. Research on path-planning algorithm integrating optimization a-star algorithm and artificial po-tential feld method. J. Electron. 2022, 11, 3660. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Tong, K.; Fu, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, X.; He, Y.; Xu, L. Hybrid path planning algorithm for robots based on modified golden jackal optimization method and dynamic window method. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 282, 127808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ling, H.; Tang, Z.; Song, W.; Lu, A. Path planning of USV in confined waters based on improved A ∗ and DWA fusion algorithm. Ocean Eng. 2025, 322, 120475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, G.; Tang, Y.M.; Leung, E.K.; Tong, P. Integrated reinforcement learning of automated guided vehicles dynamic path planning for smart logistics and operations. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2025, 196, 104008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y. Path Planning of Mobile Robot Based on Hybrid Multi-Objective Bare Bones Particle Swarm Optimization with Differential Evolution. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 44542–44555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wang, Y.; Gao, Z. Path Planning of Mobile Robot Based on Improved TD3 Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation (ICMA), Guilin, China, 7–10 August 2022; pp. 715–720. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.R.; Ibrahim, A.M.; Al Mahmud, S.; Samat, F.A.; Jasni, F.; Mardzuki, M.I. Advancing mobile robot navigation with DRL and heuristic rewards: A comprehensive review. Neurocomputing 2025, 652, 131036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalmanan, N.; Kamarudin, K.; Bakar, M.A.A.; Rahiman, M.H.F.; Zakharia, A.; Mamduh, S.M. 2D LiDAR Based Reinforcement Learning for Multi-Target Path Planning in Unknown Environment. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 35541–35555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, S.V.; Harikrishnan, R.; Ibrahim, B.S.K.K.; Ponnuru, M.D.S. Mobile robot path planning using deep deterministic policy gradient with differential gaming (DDPG-DG) exploration. Cogn. Robot. 2024, 4, 156–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Lee, G.; Lee, C. Reinforcement learning-based dynamic obstacle avoidance and integration of path planning. Intell. Serv. Robot. 2021, 14, 663–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, S.; van Hoof, H.; Meger, D. Addressing Function Approximation Error in Actor-Critic Methods. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Chen, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, S. Path planning of mobile robot based on improved TD3 algorithm in dynamic environment. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nghiem, G.-K.; Le, T.-L.; Phung, T.C.; Dinh, Q.H. A study on the optimal control strategy using sliding mode controller for Mecanum-Wheeled omnidirectional mobile robot. Measurement 2025, 255, 118113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Zhang, H.; Sun, Y.; Tao, H.; Chen, Y. A cross-platform deep reinforcement learning model for autonomous navigation without global information in different scenes. Control Eng. Pract. 2024, 150, 105991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Zhang, G.; Lu, X.; Wang, H.; Sheng, C.; Sun, L. Reinforcement learning method based on sample regularization and adaptive learning rate for AGV path planning. Neurocomputing 2024, 614, 128820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, S.; Zhao, J.; Wu, H.; Xian, J.; Montewka, J. Autonomous port management based AGV path planning and optimization via an ensemble reinforcement learning framework. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 251, 107087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zheng, S. Robot Trajectory Planning Optimization Algorithm Based on Improved TD3 Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Intelligent Communication and Networking (ICN), Changzhou, China, 10–12 November 2023; pp. 281–285. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, R.; Schuurmans, D.; Norouzi, M. An Optimistic Perspective on Offline Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning, Vienna, Austria, 13–18 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Xi, B.; Chen, S.; Gao, F.; Wang, Z.; Long, Y. The Path Planning Study of Autonomous Patrol Robot based on Modified Astar Algorithm and Genetic Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2022 34th Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC), Hefei, China, 15–17 August 2022; pp. 4713–4718. [Google Scholar]

- Koval, A.; Karlsson, S.; Nikolakopoulos, G. Experimental evaluation of autonomous map-based Spot navigation in confined environments. Biomim. Intell. Robot. 2022, 2, 100035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zai, W.; Lin, Q.; Wang, S.; Lin, X. Path Planning for Wheeled Robots Based on the Fusion of Improved A* and TEB Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2023 China Automation Congress (CAC), Chongqing, China, 17–19 November 2023; pp. 3257–3261. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).