The Electric Vehicle (EV) Revolution: How Consumption Values, Consumer Attitudes, and Infrastructure Readiness Influence the Intention to Purchase Electric Vehicles in Malaysia

Abstract

1. Introduction

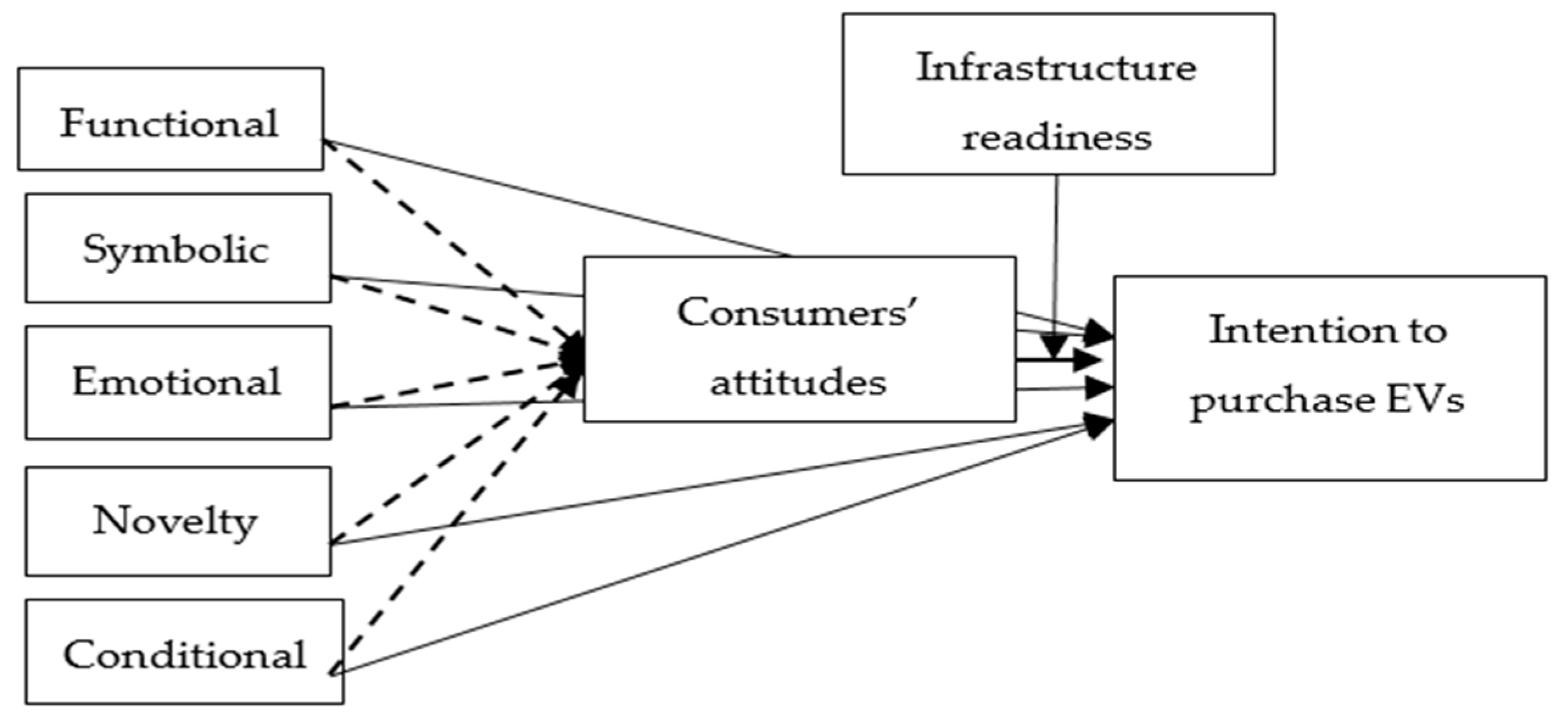

- It advances the marketing-oriented perspective in EV adoption by focusing on values and attitudes rather than only on incentives or technology.

- It empirically tests the mediating role of attitude between consumption values and intention, extending the application of TPB in the EV domain.

- It introduces infrastructure readiness as a contextual moderator, offering insights into how external enablers interact with consumer psychology in influencing EV adoption in Malaysia.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Theory of Consumption Value (TCV)

2.2. The Influence of Consumers’ Attitudes on Intentions to Purchase EVs

2.3. Mediating Effect of Consumers’ Attitudes on the Relationship Between Consumption Values and Intentions to Purchase EVs

2.4. Moderating Effect of Infrastructure Readiness on the Relationship Between Attitude and Intentions to Purchase EVs

2.5. Research Model Development

3. Methodology and Data Collection Procedure

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Assessment of Structural Model

4.3. Mediating Effect of Consumers’ Attitudes

4.4. Moderating Effect of Infrastructure Readiness

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2. Practical Contributions

6.3. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| TCV | Theory of Consumption Value |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modelling |

References

- Palea, V.; Santhià, C. The financial impact of carbon risk and mitigation strategies: Insights from the automotive industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 344, 131001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taamneh, M.M.; Makahleh, H.Y. The prospects of adopting electric vehicles in urban contexts: A systematic review of literature. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2025, 31, 101420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, K.P.C.; Kamaruddin, N.K. The Relationship between perceived benefit and perceived risk toward electric vehicle (EV) purchase intention among consumers in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Res. Manag. Technol. Bus. 2024, 5, 346–364. [Google Scholar]

- Husain, R.; Wahab, N.S.A.; Husain, R. Awareness of CO2 emission by cars and eco-friendly environment in the Malaysian automotive industry: A study on drivers’ perspectives. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2023, 13, 463–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halmee, M.D.I.; Shahlal, N.; Rusman, M.S. The significant role of emotions in the perspective of Malaysian consumers toward converting from conventional vehicles to electric vehicles. Indian-Pac. J. Account. Financ. 2025, 9, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Shafie, S.H.; Mahmud, M. Urban air pollutant from motor vehicle emissions in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2020, 20, 2793–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Wong, M.S.; Qin, K.; Zhu, R.; You, L.; Wei, J. Electric vehicle attributed future air pollution alleviation: A case study in Guangdong province, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 391, 126442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, N.A.M.; Sari, M.N.M.; Muhammad, A.; Isa, F.M. Consumption values as determinants of electric car purchase intention among Malaysian consumers. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Sci. 2021, 11, 16–28. [Google Scholar]

- Muzir, N.A.Q.; Mojumder, M.R.H.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Selvaraj, J. Challenges of electric vehicles and their prospects in Malaysia: A comprehensive review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, S.; Nilashi, M.; Iranmanesh, M.; Ghobakhloo, M.; Samad, S.; Alghamdi, A.; Mohd, S. Drivers and barriers of electric vehicle usage in Malaysia: A DEMATEL approach. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 177, 105965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulzari, A.; Wang, Y.; Prybutok, V. A green experience with eco-friendly cars: A young consumer electric vehicle rental behavioural model. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 65, 102877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsan, F.; Habib, S.; Gulzar, M.M.; Guo, J.; Muyeen, S.M.; Kamwa, I. Assessing policy influence on electric vehicle adoption in China: An in-Depth study. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 54, 101471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.R.; Alok, K. Adoption of electric vehicle: A literature review and prospects for sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253, 119911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, G. Understanding and identifying barriers to electric vehicle adoption through thematic analysis. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2021, 10, 100364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska-Pyzalska, A. Perspectives of development of low emission zones in Poland: A short review. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 898391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, N.A.M.; Wen, T.C. Assessing consumers’ purchase intention: As hybrid car study in Malaysia. Soc. Sci. 2016, 11, 2795–2801. [Google Scholar]

- Shoukat, A.; Baig, U.; Batool Hussain, D.; Rehman, N.A.; Shakir, D.K. An empirical study of consumption values on green purchase intention. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2021, 10, 140–148. [Google Scholar]

- Adepetu, A.; Keshav, S. The relative importance of price and driving range on electric vehicle adoption: Los Angeles case study. Transportation 2017, 44, 353–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, A.; Nicoletti, L.; Schröder, D.; Wolff, S.; Waclaw, A.; Lienkamp, M. An overview of parameter and cost for battery electric vehicles. World Electr. Veh. J. 2021, 12, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, M.; Scott, H.; Baglee, D. The effect of driving style on electric vehicle performance, economy and perception. Int. J. Electr. Hybrid. Veh. 2012, 4, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczak, H.; Droździel, P. Analysis of pollutants emission into the air at the stage of an electric vehicle operation. J. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 22, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, J.; Lee, C. Does driving range of electric vehicles influence electric vehicle adoption? Sustainability 2017, 9, 1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, N.; Nordin, S.M.; Rahman, I.; Vasant, P.; Noor, M.A. An overview of electric vehicle technology: A vision towards sustainable transportation. In Intelligent Transportation and Planning: Breakthroughs in Research and Practice; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 292–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Ahmad, M. Relating consumers’ information and willingness to buy electric vehicles: Does personality matter? Transp. Res. Part. D Environ. 2021, 100, 103049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junquera, B.; Moreno, B.; Álvarez, R. Analyzing consumer attitudes towards electric vehicle purchasing intentions in Spain: Technological limitations and vehicle confidence. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2016, 109, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Yao, E.; Jin, F.; Yang, Y. Analysis of incentive policies for electric vehicle adoptions after the abolishment of purchase subsidy policy. Energy 2022, 239, 122136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tissayakorn, K. Consumers’ decisions to purchase electric vehicles in Bangkok, Thailand. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2025, 21, 101536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Guo, Y.; Souders, D.J.; Li, X.; Yang, M.; Xu, X.; Qian, X. Moderating effects of policy measures on intention to adopt autonomous vehicles: Evidence from China. Travel Behav. Soc. 2025, 38, 100921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, S.A.; Ahmad, F.; Al-Wahedi, A.M.A.; Iqbal, A.; Ali, A. Navigating the complex realities of electric vehicle adoption: A comprehensive study of government strategies, policies, and incentives. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 53, 101379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Newman, B.I.; Gross, B.L. Why we buy what we buy: A Theory of Consumption Values. J. Bus. Res. 1991, 22, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behaviour. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haustein, S.; Jensen, A.F. Factors of electric vehicle adoption: A comparison of conventional and electric car users based on an extended Theory of Planned Behavior. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2018, 12, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Wu, D.; Zhang, L. Economic, functional, and social factors influencing electric vehicles’ adoption: An empirical study based on the diffusion of innovation theory. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.S.; Kim, Y.; Roh, T. Pro-environmental behavior on electric vehicle use intention: Integrating Value-Belief-Norm Theory and Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 418, 138211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaglieri, L.F.; Francesco, M.; Luca, F. Investigating consumer behaviour towards electric vehicles: A systematic literature review. Circ. Econ. Sust. 2025, 5, 1419–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf Javid, M.; Ali, N.; Abdullah, M.; Campisi, T.; Shah, S.A.H. Travelers’ adoption behavior towards electric vehicles in Lahore, Pakistan: An extension of Norm Activation Model (NAM) Theory. J. Adv. Transp. 2021, 1, 7189411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Shan, X.; Guo, M.; Gao, W.; Lin, Y.S. Design and application of experience management tools from the perspective of customer perceived value: A study on the electric vehicle market. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Ding, Z.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Jiang, X.; Sun, W.; Liu, M. The relationship between symbolic meanings and adoption intention of electric vehicles in China: The moderating effects of consumer self-identity and face consciousness. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 288, 125116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, S.; Talwar, M.; Kaur, P.; Dhir, A. Consumers’ resistance to digital innovations: A systematic review and framework development. Australas. Mark. J. 2020, 28, 286–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravindan, K.L.; Ramayah, T.; Thavanethen, M.; Raman, M.; Ilhavenil, N.; Annamalah, S.; Choong, Y.V. Modeling positive electronic word of mouth and purchase intention using Theory of Consumption Value. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanrikulu, C. Theory of Consumption Values in consumer behaviour research: A review and future research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 1176–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahoo, S.; Umar, R.M.; Mason, M.C.; Zamparo, G. Role of Theory of Consumption Values in consumer consumption behavior: A review and agenda. Int. Rev. Retail Distrib. Consum. Res. 2024, 34, 417–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, D.; Siddiqui, M.; Siddiqui, A. Can initial trust boost intention to purchase Ayurveda products? A theory of consumption value (TCV) perspective. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 2521–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. The impact of consumption values on environmentally friendly product purchase decision. J. Econ. Mark. Manag. 2021, 9, 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Ariffin, S.K.; Richardson, C.; Wang, Y. Influencing factors of customer loyalty in mobile payment: A consumption value perspective and the role of alternative attractiveness. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 73, 103302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaerudin, S.M.; Syafarudin, A. The effect of product quality, service quality, price on product purchasing decisions on consumer satisfaction. Ilomata Int. J. Tax Account. 2021, 2, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.L.; Kim, K. Role of consumption values in the luxury brand experience: Moderating effects of category and the generation gap. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 57, 102249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijekoon, R.; Sabri, M.F. Determinants that influence green product purchase intention and behaviour: A literature review and guiding framework. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, S.; Tarun, M.T. Effect of consumption values on customers’ green purchase intention: A mediating role of green trust. Soc. Responsib. J. 2021, 17, 1320–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Zhang, Q. Green purchase intention: Effects of electronic service quality and customer green psychology. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 267, 122053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkaya, M. Understanding the impacts of lifestyle segmentation & perceived value on brand purchase intention: An empirical study in different product categories. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2021, 27, 100155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, D.; Paul, J. Healthcare apps’ purchase intention: A consumption values perspective. Technovation 2023, 120, 102481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Nonino, F.; Pompei, A. Which are the determinants of green purchase behaviour? A study of Italian consumers. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 2600–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Meng, F.; Jeong, M.; Zhang, Z. To follow others or be yourself? Social influence in online restaurant reviews. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 1067–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansori, S.; Safari, M.; Mohd Ismail, Z.M. An analysis of the religious, social factors and income’s influence on the decision making in Islamic microfinance schemes. J. Islam. Account. Bus. Res. 2020, 11, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajeddini, K.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Gamage, T.C.; Martin, E. Exploring the visitors’ decision-making process for Airbnb and hotel accommodations using value-attitude-behavior and theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 96, 102950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, S.; He, Z.; Li, C.; Meng, X. Factors Influencing Adoption intention for electric vehicles under a subsidy deduction: From different city-level perspectives. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Abbas, J.; Álvarez-Otero, S.; Khan, H.; Cai, C. Interplay between corporate social responsibility and organizational green culture and their role in employees’ responsible behaviour towards the environment and society. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 366, 132878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, H.L.; Martinez, L.M.; Martinez, L.F. Sustainability efforts in the fast fashion industry: Consumer perception, trust and purchase intention. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2021, 12, 571–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, A.; Kaur, P.; Bhatt, Y.; Mäntymäki, M.; Dhir, A. Why do people purchase from food delivery apps? A consumer value perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 63, 102667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek, A.C.; Malekpour, S.; Raven, R.; Court, E.; Byrne, E. Towards environmentally sustainable food systems: Decision-making factors in sustainable food production and consumption. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 610–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangi, N.; Gupta, S.K.; Narula, S.A. Consumer buying behaviour and purchase intention of organic food: A conceptual framework. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2020, 31, 1515–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlShurman, B.A.; Khan, A.F.; Mac, C.; Majeed, M.; Butt, Z.A. What demographic, social, and contextual factors influence the intention to use COVID-19 vaccines: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, M.T.; Lu, P.; Parrella, J.A.; Leggette, H.R. Consumer acceptance toward functional foods: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kautish, P.; Sharma, R. Study on relationships among terminal and instrumental values, environmental consciousness and behavioural intentions for green products. J. Indian Bus. Res. 2021, 13, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suphasomboon, T.; Vassanadumrongdee, S. Toward sustainable consumption of green cosmetics and personal care products: The role of perceived value and ethical concern. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 33, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Pham, T.L.; Dang, V.T. Environmental consciousness and organic food purchase intention: A moderated mediation model of perceived food quality and price sensitivity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, B.; Sheng, G.; She, S.; Xu, J. Impact of consumer environmental responsibility on green consumption behaviour in China: The role of environmental concern and price sensitivity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimul, A.S.; Cheah, I. Consumers’ preference for eco-friendly packaged products: Pride vs guilt appeal. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2023, 41, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Dong, F. Why do consumers make green purchase decisions? Insights from a systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6607. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, K.; Trott, S.; Sahadev, S.; Singh, R. Emotions and consumer behaviour: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 2396–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veale, D.; Robins, E.; Thomson, A.B.; Gilbert, P. No safety without emotional safety. Lancet Psychiatry 2023, 10, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Liao, P.C. Re-thinking the mediating role of emotional valence and arousal between personal factors and occupational safety attention levels. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallego-Alberto, L.; Losada, A.; Márquez-González, M.; Romero-Moreno, R.; Vara, C. Commitment to personal values and guilt feelings in dementia caregivers. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2017, 29, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, C.; Keller, B.; Silver, C.F.; Hood, R.W.; Streib, H. Positive adult development and “spirituality”: Psychological well-being, generativity, and emotional stability. In Semantics and Psychology of Spirituality: A Cross-Cultural Analysis; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 401–436. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, X.M.; Song, L.J.; Wu, J. Is it new? Personal and contextual influences on perceptions of novelty and creativity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.N.; Mohsin, M. The power of emotional value: Exploring the effects of values on green product consumer choice behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 150, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karjaluoto, H.; Shaikh, A.A.; Saarijärvi, H.; Saraniemi, S. How perceived value drives the use of mobile financial services apps. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 47, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.; Soutar, G.; Ashill, N.J.; Naumann, E. Value drivers and adventure tourism: A comparative analysis of Japanese and Western consumers. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2017, 7, 102–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettiarachchi, W.N.; Lakmal, H.A. The impact of perceived value on satisfaction of adventure tourists: With special reference to Sri Lankan domestic tourists. Colombo Bus. J. 2018, 9, 80–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, J.H., III; Ness, A.M.; Mecca, J. Outside the box: Epistemic curiosity as a predictor of creative problem solving and creative performance. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 104, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Johnson, K.K. Influences of environmental and hedonic motivations on intention to purchase green products: An extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 18, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Sun, S.; Liu, C.; Chang, V. Consumer innovativeness, product innovation and smart toys. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2020, 41, 100974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, H.; Yan, L.; Guo, R.; Saeed, A.; Ashraf, B.N. The defining role of environmental self-identity among consumption values and behavioural intention to consume organic food. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Dhir, A.; Talwar, S.; Ghuman, K. The value proposition of food delivery apps from the perspective of Theory of Consumption Value. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 1129–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, E.; Kim, Y.G. Consumer attitudes and buying behavior for green food products: From the aspect of green perceived value (GPV). Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candan, B.; Yıldırım, S. Investigating the relationship between consumption values and personal values of green product buyers. Int. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2013, 2, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Foropon, C. Green product attributes and green purchase behavior: A theory of Planned Behavior perspective with implications for circular economy. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 1018–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.T.; Liu, Y.; Mo, Z. Moral norm is the key: An extension of the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) on Chinese consumers’ green purchase intention. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 32, 1823–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.V.; Nguyen, C.H.; Hoang, T.T.B. Green consumption: Closing the intention-behavior gap. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuttavuthisit, K.; Thøgersen, J. The importance of consumer trust for the emergence of a market for green products: The case of organic food. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.C.; Wang, H.M.; Huang, H.L.; Ho, C.W. Consumer attitude and purchase intention toward rooftop photovoltaic installation: The roles of personal trait, psychological benefit, and government incentives. Energy Environ. 2020, 31, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyükdağ, N.; Soysal, A.N.; Kïtapci, O. The effect of specific discount pattern in terms of price promotions on perceived price attractiveness and purchase intention: An experimental research. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Cao, H.; Liu, Y. Green innovation, privacy regulation and environmental policy. Renew. Energy 2023, 203, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissmann, M.A.; Hock, R.L.T. Making sustainable consumption decisions: The effects of product availability on product purchase intention. J. Glob. Mark. 2022, 35, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.D.; Pallonetti, N. Rebate influence on electric vehicle adoption in California. In Proceedings of the 36th International Electric Vehicle Symposium (EVS36), Sacramento, CA, USA, 11–14 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, D.; Kaur, R. Does electronic word-of-mouth influence e-recruitment adoption? A mediation analysis using the PLS-SEM approach. Manag. Res. Rev. 2023, 46, 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzir, M.U.H.; Jerin, I.; Al Halbusi, H.; Hamid, A.B.A.; Latiff, A.S.A. Does quality stimulate customer satisfaction where perceived value mediates and the usage of social media moderates? Heliyon 2020, 6, e05710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, S.S.; Solaiman, M. Moral identity, consumption values and green purchase behaviour. J. Islam. Mark. 2023, 14, 2550–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah, F.; Radder, L.; van Eyk, M. Perceived experience value, satisfaction and behavioural intentions: A guesthouse experience. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2016, 7, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, E. Rebirth fashion: Second hand clothing consumption values and perceived risks. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 273, 122951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A.; Das, B.; She, L. What affects consumers’ choice behaviour towards organic food restaurants? By applying organic food consumption value model. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2024, 7, 2582–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M.; Lohmann, S.; Albarracín, D. The influence of attitudes on behaviour. Handb. Attitudes 2018, 1, 197–255. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Cote, N.G. Attitudes and the prediction of behaviour. Attitudes Attitude Change 2008, 13, 289–305. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Y.K.; Wu, W.Y.; Pham, T.T. Examining the moderating effects of green marketing and green psychological benefits on customers’ green attitude, value and purchase intention. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moons, I.; De Pelsmacker, P. Emotions as determinants of electric car usage intention. J. Mark. Manag. 2012, 28, 195–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazhar, W.; Jalees, T.; Asim, M.; Alam, S.H.; Zaman, S.I. Psychological consumer behavior and sustainable green food purchase. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2022, 34, 2350–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.J. Attitudes and behavior. In Social Psychology; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 347–377. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, V.K.; Chandra, B.; Kumar, S. Values and ascribed responsibility to predict consumers’ attitude and concern towards green hotel visit intention. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 96, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashari, Z.A.; Ko, J.; Jang, J. Consumers’ intention to purchase electric vehicles: Influences of user attitude and perception. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.J.; Rose, J.M.; Greaves, S.P. I can’t believe your attitude: A joint estimation of best worst attitudes and electric vehicle choice. Transportation 2017, 44, 753–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, S.S.; Hota, S.L.; Kumar, A.; Agarwall, H. The influence of eco-friendly marketing tools on sustainable consumer choices: A comprehensive review study. Environ. Soc. Psychol. 2024, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paço, A.; Lavrador, T. Environmental knowledge and attitudes and behaviours towards energy consumption. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 197, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcinkowski, T.; Reid, A. Reviews of research on the attitude–behavior relationship and their implications for future environmental education research. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.L.; Ooi, H.Y.; Goh, Y.N. The influence of environmental concern and social norms on green purchase behavior: Malaysian evidence. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Jakučionytė-Skodienė, M.; Dagiliūtė, R.; Liobikienė, G. Do general pro-environmental behaviour, attitude, and knowledge contribute to energy savings and climate change mitigation in the residential sector? Energy 2020, 193, 116784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, M.; Warren-Myers, G.; Paladino, A. Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour to predict intentions to purchase sustainable housing. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.J.; Choi, Y.J.; Oh, K.W. Influencing factors of Chinese consumers’ purchase intention to sustainable apparel products: Exploring consumer “attitude–behavioral intention” gap. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachman, E.S.; Amarullah, D. Halal cosmetics repurchase intention: Theory of consumption values perspective. J. Islam. Mark. 2024, 15, 3666–3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehzadeh, R.; Pool, J.K. Brand attitude and perceived value and purchase intention toward global luxury brands. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2017, 29, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indriani, I.A.D.; Rahayu, M.; Hadiwidjojo, D. The influence of environmental knowledge on green purchase intention the role of attitude as mediating variable. Int. J. Multicult. Multirel. Underst. 2019, 6, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogiemwonyi, O.; Alam, M.N.; Alshareef, R.; Alsolamy, M.; Azizan, N.A.; Mat, N. Environmental factors affecting green purchase behaviours of the consumers: Mediating role of environmental attitude. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2023, 10, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.W.; Siddik, A.B.; Masukujjaman, M.; Alam, S.S.; Akter, A. Perceived environmental responsibilities and green buying behavior: The mediating effect of attitude. Sustainability 2020, 13, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhu, N.; Dai, Q. Consumer ethnocentrism, product attitudes and purchase intentions of domestic products in China. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Engineering and Business Management, Chengdu, China, 25–27 March 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, J.F.; Wu, S.C.; Kathinthong, P.; Tran, T.H.; Lin, M.H. Electric vehicle adoption barriers in Thailand. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzini, P. Charging ahead: A survey-based study of Italian consumer readiness for electric vehicle adoption. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, M.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, K.; Ye, X. Range anxiety and willingness to pay: Psychological insights for electric vehicle. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2025, 17, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pevec, D.; Babic, J.; Carvalho, A.; Ghiassi-Farrokhfal, Y.; Ketter, W.; Podobnik, V. A survey-based assessment of how existing and potential electric vehicle owners perceive range anxiety. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276, 122779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higueras-Castillo, E.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F.; Santos, M.A.D.; Zulauf, K.; Wagner, R. Do you believe it? Green advertising skepticism and perceived value in buying electric vehicles. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 4671–4685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Xin, Y.; Zhang, Z. Eco-label knowledge versus environmental concern toward consumer’s switching intentions for electric vehicles: A roadmap toward green innovation and environmental sustainability. Energy Environ. 2023, 36, 356–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D.; Harbrecht, A.; Surmann, A.; McKenna, R. Electric vehicles’ impacts on residential electric local profiles–A stochastic modelling approach considering socio-economic, behavioural and spatial factors. Appl. Energy 2019, 233, 644–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, M.P.; Bagen, B.; Rajapakse, A. Probabilistic reliability evaluation of distribution systems considering the spatial and temporal distribution of electric vehicles. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 117, 105609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miele, A.; Axsen, J.; Wolinetz, M.; Maine, E.; Long, Z. The role of charging and refuelling infrastructure in supporting zero-emission vehicle sales. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 81, 102275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liu, X.; Yu, J.; Okubo, K. Residual performance evaluation of electric vehicle batteries: Focusing on the analysis results of a social survey of vehicle owners. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Chaveeesuk, S.; Chaiyasoonthorn, W. The adoption of electric vehicle in Thailand with the moderating role of charging infrastructure: An extension of a UTAUT. Int. J. Sustain. Energy 2024, 43, 2387908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, P.; Kumar, A.; Parayitam, S.; Luthra, S. Understanding transport users’ preferences for adopting electric vehicle based mobility for sustainable city: A moderated moderated-mediation model. J. Transp. Geogr. 2023, 106, 103520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabush, I.; Battat, I.; Cohen, C.; Lavee, D. Navigating the electric vehicle revolution: Optimal subsidy allocation for electric vehicles and charging infrastructure. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 486, 144586. [Google Scholar]

- Okika, M.C.; Musonda, I.; Monko, R.J.; Phoya, S.A. The road map for sustainable development using solar energy electricity generation in Tanzania. Energy Strategy Rev. 2025, 57, 101630. [Google Scholar]

- Skippon, S.M.; Kinnear, N.; Lloyd, L.; Stannard, J. How experience of use influences mass-market drivers’ willingness to consider a battery electric vehicle: A randomised controlled trial. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2016, 92, 26–42. [Google Scholar]

- Afroz, R.; Rahman, A.; Masud, M.M.; Akhtar, R.; Duasa, J.B. How individual values and attitude influence consumers’ purchase intention of electric vehicles—Some insights from Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Environ. Urban. ASIA 2015, 6, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Aquino, R.S.; Hall, C.M.; Chen, N.; Fieger, P. Is Gen Z really that different? Environmental attitudes, travel behaviours and sustainability practices of international tourists to Canterbury, New Zealand. J. Sustain. Tour. 2025, 33, 1016–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, M.A.; Seyfi, S.; Elhoushy, S.; Woosnam, K.M.; Patwardhan, V. Determinants of generation Z pro-environmental travel behaviour: The moderating role of green consumption values. J. Sustain. Tour. 2025, 33, 1079–1099. [Google Scholar]

- Coffman, M.; Bernstein, P.; Wee, S. Electric vehicles revisited: A review of factors that affect adoption. Transp. Rev. 2017, 37, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Wu, W. Why people want to buy electric vehicle: An empirical study in first-tier cities of China. Energy Policy 2018, 112, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Tian, S.; Sunny Tsai, W.H.; Seelig, M.I. The power of emotional appeal in motivating behaviors to mitigate climate change among generation Z. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2024, 36, 37–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanchanapibul, M.; Lacka, E.; Wang, X.; Chan, H.K. An empirical investigation of green purchase behaviour among the young generation. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 66, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.T.J.; Sheu, C. Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour to green hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.H.; Gowrie, V.; Madi Abdullah, M.; Nasreen, K. A study of hybrid car adoption in Malaysia. In Proceedings of the 2nd Annual Summit on Business and Entrepreneurial Studies (2nd ASBES 2012), Kuching, Malaysia, 15–16 October 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K. Gender differences in Hong Kong adolescent consumers’ green purchasing behaviour. J. Consum. Mark. 2009, 26, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, Y.N.; Beckhet, A.B. Exploring factors influencing electric vehicle usage intention: An empirical study in Malaysia. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2015, 16, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.C.; Huang, Y.H. The influence factors on choice behaviour regarding green products based on the theory of consumption values. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 22, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, C.W.; Mohd Noor, N.A. What affects Malaysian consumers’ intention to purchase hybrid car? Asian Soc. Sci. 2015, 11, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using IBM SPSS; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Kang, W.; Li, L.; Wang, Z. Why do consumers choose to buy electric vehicles? A paired data analysis of purchase intention configurations. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2021, 147, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Sari, M.N.B. Consumption Values and Consumers’ Attitude towards Intention to Purchase Electric Car among Malaysian Consumers. DBA Thesis, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Sintok, Malaysia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLSSEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, M.A.; Ramayah, T.; Cheah, J.H.; Ting, H.; Chuah, F.; Cham, T.H. PLS-SEM statistical programs: A review. J. Appl. Struct. Equ. Model. 2021, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramayah, T.J.F.H.; Cheah, J.; Chuah, F.; Ting, H.; Memon, M.A. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) using SmartPLS 3; Pearson: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Moderation Analysis. In Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) Using a Workbook; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 155–172. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cheah, J.H.; Nitzl, C.; Roldán, J.; Cepeda-Carrion, G.; Gudergan, S.P. A primer on the conditional mediation analysis in PLS-SEM. Data Base Adv. Inf. Syst. 2021, 52, 43–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadil, Y.; Jeyaraj, A.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Rana, N.P.; Sarker, P. A meta-analysis of the factors associated with s-commerce intention: Hofstede’s cultural dimensions as moderators. Internet Res. 2022, 33, 2013–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, D.; Harichandan, S.; Kar, S.K. An empirical study on consumer motives and attitude towards adoption of electric vehicles in India: Policy implications for stakeholders. Energy Policy 2022, 165, 112941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, P.; Kulshreshtha, K.; Tripathi, V.; Agnihotri, D. Exploring consumers’ motives for electric vehicle adoption: Bridging the attitude–behavior gap. Benchmarking Int. J. 2023, 30, 4174–4192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonchunone, S.; Nami, M.; Krommuang, A.; Phonsena, A.; Suwunnamek, O. Exploring the effects of perceived values on consumer usage intention for electric vehicle in Thailand: The mediating effect of satisfaction. Acta Logist. 2023, 10, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharum, S.M.; Md Isa, N.; Salahuddin, N.; Saad, S. The relationship between dimension of consumption value and intention to purchase of green products. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2017, 5, 215–221. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Hu, Y. Understanding the role of emotions in consumer adoption of electric vehicles: The mediating effect of perceived value. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2022, 65, 84–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chi, Y.; Xu, J.H.; Yuan, Y. Consumers’ attitudes and their effects on electric vehicle sales and charging infrastructure construction: An empirical study in China. Energy Policy 2022, 165, 112983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamil, A.M.; Ali, S.; Akbar, M.; Zubr, V.; Rasool, F. The consumer purchase intention toward hybrid electric car: A utilitarian-hedonic attitude approach. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1101258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theocharis, D.; Tsekouropoulos, G. Sustainable consumption and branding for Gen Z: How brand dimensions influence consumer behavior and adoption of newly launched technological products. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, Z.; Jansson, J.; Bodin, J. Advances in consumer electric vehicle adoption research: A review and research agenda. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2015, 34, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, S.; Buch, K.; Freling, C.; Hardman, S.; Firestone, J. Electric vehicles and rooftop solar energy: Consumption values influencing decisions and barriers to co-adoption in the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2025, 122, 103990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alganad, A.M.N.; Isa, N.M.; Fauzi, W.I.M. Boosting green cars retail in Malaysia: The influence of conditional value on consumers’ behaviour. J. Distrib. Sci. 2021, 19, 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.H.; Omar, A.; Zainuddin, N. Barriers to the adoption of electric vehicles in Malaysia: The moderating role of infrastructure readiness. Energy Policy 2019, 132, 127–135. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.S.; Haque, A.; Ahmad, M.I.S. Car ownership as a symbol of social status: A study among Malaysian consumers. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2017, 18, 801–818. [Google Scholar]

- Yusof, Y.; Wahid, N.A.; Ismail, I. Social influence and pro-environmental purchase intentions: A Malaysian perspective. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 7341–7359. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S.; Rahman, M.S.; Khan, M. Consumer perception of electric vehicles: Evidence from an emerging economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276, 124249. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.S.; Haque, A.; Ahmad, M.I.S. Consumer intention toward electric vehicle adoption: The moderating role of policy incentives in Malaysia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 61024–61036. [Google Scholar]

- Karia, N.; Wong, C.Y.; Asaari, M.H.A.H. Factors influencing electric vehicle adoption in Malaysia: The role of incentives and infrastructure. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7113. [Google Scholar]

- Palm, A. Early adopters and their motives: Differences between earlier and later adopters of residential solar photovoltaics. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 133, 110142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaei-Zadeh, A.; Wong, T.K.; Hanifah, H.; Teoh, A.P.; Nawaser, K. Modelling electric vehicle purchase intention among generation Y consumers in Malaysia. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2022, 43, 100784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriram, K.V.; Michael, L.K.; Hungund, S.S.; Fernandes, M. Factors influencing adoption of electric vehicles–A case in India. Cogent Eng. 2022, 9, 2085375. [Google Scholar]

- Loudiyi, H.; Chetioui, Y.; Lebdaoui, H. Economics of electric vehicle adoption: An integrated framework for investigating the antecedents of perceived value and purchase intent. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2022, 12, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, B.; Hwang, H.G. Consumers purchase intentions of green electric vehicles: The influence of consumers technological and environmental considerations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 147 | 55.7 |

| Female | 117 | 44.3 | |

| Age | Gen Z (25–30 years) | 41 | 15.5 |

| Gen Y (31–40 years) | 67 | 25.4 | |

| Gen X (41–50 years) | 120 | 45.5 | |

| Baby boomers (51 and above) | 36 | 13.6 | |

| Education | Secondary Level | 37 | 14.0 |

| Diploma | 52 | 19.7 | |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 89 | 33.7 | |

| Master’s Degree | 68 | 25.8 | |

| Doctoral | 11 | 4.2 | |

| Others | 7 | 2.7 | |

| Marital Status | Single | 56 | 21.2 |

| Married | 204 | 77.3 | |

| Divorced/Widowed | 4 | 1.5 | |

| Occupation | Public sector | 34 | 12.9 |

| Private Sector | 196 | 74.2 | |

| Self-Employed | 24 | 9.1 | |

| Retired/Pensioner | 3 | 1.1 | |

| Others | 7 | 2.7 |

| Construct | AVE | Composite Reliability |

|---|---|---|

| Intention to purchase EV(IP) | 0.878 | 0.743 |

| Consumers’ attitudes (CA) | 0.954 | 0.749 |

| Infrastructure Readiness (IR) | 0.836 | 0.730 |

| Functional Value (FV) | 0.938 | 0.690 |

| Symbolic Value (SV) | 0.894 | 0.746 |

| Emotional Value (EV) | 0.963 | 0.764 |

| Novelty Value (NV) | 0.916 | 0.746 |

| Conditional Value (CV) | 0.835 | 0.730 |

| Items | IP | CA | IR | FV | CV | EV | NV | SV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IP1 | 0.791 | 0.525 | 0.198 | 0.484 | 0.408 | 0.510 | 0.376 | 0.370 |

| IP4 | 0.780 | 0.517 | 0.240 | 0.393 | 0.409 | 0.560 | 0.438 | 0.404 |

| IP5 | 0.821 | 0.701 | 0.087 | 0.605 | 0.296 | 0.551 | 0.172 | 0.529 |

| IP6 | 0.814 | 0.603 | 0.190 | 0.436 | 0.340 | 0.556 | 0.278 | 0.395 |

| CA1 | 0.675 | 0.842 | 0.185 | 0.641 | 0.379 | 0.647 | 0.371 | 0.548 |

| CA2 | 0.578 | 0.831 | 0.181 | 0.532 | 0.389 | 0.616 | 0.316 | 0.492 |

| CA3 | 0.654 | 0.898 | 0.204 | 0.576 | 0.405 | 0.654 | 0.306 | 0.540 |

| CA4 | 0.665 | 0.879 | 0.257 | 0.596 | 0.429 | 0.679 | 0.356 | 0.563 |

| CA5 | 0.666 | 0.887 | 0.176 | 0.585 | 0.421 | 0.647 | 0.278 | 0.528 |

| CA6 | 0.622 | 0.867 | 0.111 | 0.601 | 0.369 | 0.629 | 0.297 | 0.590 |

| CA7 | 0.605 | 0.851 | 0.170 | 0.657 | 0.410 | 0.681 | 0.350 | 0.562 |

| IR1 | 0.159 | 0.111 | 0.767 | 0.182 | 0.340 | 0.188 | 0.307 | 0.044 |

| IR4 | 0.133 | 0.147 | 0.746 | 0.159 | 0.230 | 0.158 | 0.233 | 0.095 |

| IR5 | 0.212 | 0.230 | 0.863 | 0.223 | 0.313 | 0.273 | 0.458 | 0.116 |

| FV1 | 0.462 | 0.489 | 0.223 | 0.759 | 0.373 | 0.567 | 0.351 | 0.532 |

| FV3 | 0.501 | 0.576 | 0.063 | 0.813 | 0.256 | 0.558 | 0.271 | 0.576 |

| FV4 | 0.519 | 0.610 | 0.208 | 0.854 | 0.341 | 0.611 | 0.341 | 0.589 |

| FV5 | 0.515 | 0.612 | 0.286 | 0.823 | 0.353 | 0.600 | 0.397 | 0.524 |

| FV6 | 0.495 | 0.625 | 0.151 | 0.856 | 0.285 | 0.602 | 0.265 | 0.587 |

| FV7 | 0.486 | 0.606 | 0.241 | 0.798 | 0.414 | 0.576 | 0.452 | 0.505 |

| FV8 | 0.422 | 0.458 | 0.106 | 0.706 | 0.308 | 0.457 | 0.315 | 0.428 |

| FV9 | 0.497 | 0.519 | 0.182 | 0.813 | 0.372 | 0.578 | 0.378 | 0.501 |

| FV10 | 0.397 | 0.394 | 0.277 | 0.704 | 0.402 | 0.506 | 0.489 | 0.397 |

| FV10 | 0.397 | 0.394 | 0.277 | 0.704 | 0.402 | 0.506 | 0.489 | 0.397 |

| CV3 | 0.173 | 0.220 | 0.313 | 0.195 | 0.721 | 0.299 | 0.428 | 0.168 |

| CV4 | 0.209 | 0.273 | 0.287 | 0.212 | 0.777 | 0.342 | 0.383 | 0.191 |

| CV5 | 0.518 | 0.491 | 0.311 | 0.480 | 0.876 | 0.544 | 0.430 | 0.440 |

| EV1 | 0.580 | 0.625 | 0.223 | 0.602 | 0.470 | 0.858 | 0.439 | 0.618 |

| EV2 | 0.584 | 0.674 | 0.231 | 0.630 | 0.479 | 0.876 | 0.410 | 0.625 |

| EV3 | 0.599 | 0.697 | 0.249 | 0.652 | 0.459 | 0.899 | 0.430 | 0.652 |

| EV4 | 0.649 | 0.748 | 0.250 | 0.706 | 0.516 | 0.915 | 0.450 | 0.669 |

| EV5 | 0.586 | 0.659 | 0.264 | 0.628 | 0.452 | 0.869 | 0.496 | 0.616 |

| EV6 | 0.572 | 0.590 | 0.226 | 0.564 | 0.467 | 0.863 | 0.543 | 0.584 |

| EV7 | 0.599 | 0.650 | 0.214 | 0.603 | 0.469 | 0.904 | 0.474 | 0.660 |

| EV8 | 0.570 | 0.600 | 0.220 | 0.566 | 0.457 | 0.805 | 0.463 | 0.558 |

| NV1 | 0.201 | 0.250 | 0.471 | 0.292 | 0.429 | 0.297 | 0.776 | 0.180 |

| NV2 | 0.249 | 0.239 | 0.421 | 0.306 | 0.451 | 0.322 | 0.827 | 0.171 |

| NV3 | 0.252 | 0.262 | 0.339 | 0.312 | 0.377 | 0.388 | 0.756 | 0.284 |

| NV4 | 0.299 | 0.316 | 0.342 | 0.375 | 0.409 | 0.447 | 0.819 | 0.297 |

| NV5 | 0.401 | 0.337 | 0.314 | 0.386 | 0.390 | 0.486 | 0.846 | 0.322 |

| NV6 | 0.374 | 0.361 | 0.292 | 0.446 | 0.422 | 0.522 | 0.796 | 0.329 |

| SV2 | 0.420 | 0.474 | 0.172 | 0.494 | 0.337 | 0.586 | 0.323 | 0.750 |

| SV3 | 0.345 | 0.448 | 0.152 | 0.434 | 0.290 | 0.509 | 0.306 | 0.715 |

| SV6 | 0.385 | 0.434 | 0.057 | 0.432 | 0.200 | 0.393 | 0.056 | 0.714 |

| SV7 | 0.368 | 0.433 | 0.026 | 0.496 | 0.302 | 0.457 | 0.168 | 0.732 |

| SV8 | 0.362 | 0.435 | 0.029 | 0.450 | 0.239 | 0.420 | 0.094 | 0.736 |

| SV10 | 0.444 | 0.540 | 0.116 | 0.567 | 0.333 | 0.663 | 0.414 | 0.767 |

| SV11 | 0.426 | 0.487 | 0.110 | 0.494 | 0.304 | 0.621 | 0.348 | 0.758 |

| Construct | CV | CA | EV | FV | IR | IP | EV | SV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CV | 0.794 | |||||||

| CA | 0.463 | 0.865 | ||||||

| EV | 0.539 | 0.752 | 0.874 | |||||

| FV | 0.430 | 0.692 | 0.710 | 0.794 | ||||

| IR | 0.373 | 0.213 | 0.269 | 0.241 | 0.794 | |||

| IP | 0.448 | 0.738 | 0.678 | 0.604 | 0.217 | 0.802 | ||

| NV | 0.510 | 0.376 | 0.528 | 0.450 | 0.437 | 0.384 | 0.804 | |

| SV | 0.390 | 0.632 | 0.714 | 0.654 | 0.110 | 0.534 | 0.340 | 0.739 |

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Path Coefficients | Std. Error | t-Value | p Values | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | Functional Value -> Intention to purchase EV | 0.086 | 0.074 | 1.163 | 0.245 | Rejected |

| H1b | Symbolic Value -> Intention to purchase EV | −0.017 | 0.073 | 0.231 | 0.817 | Rejected |

| H1c | Emotional Value -> Intention to purchase EV | 0.216 | 0.090 | 2.390 ** | 0.017 | Supported |

| H1d | Novelty Value -> Intention to purchase EV | 0.019 | 0.056 | 0.331 | 0.741 | Rejected |

| H1e | Conditional Value -> Intention to purchase EV | 0.064 | 0.054 | 1.168 | 0.243 | Rejected |

| H2 | Consumers’ attitudes towards EV -> Intention to purchase EV | 0.489 | 0.068 | 7.225 * | 0.000 | Supported |

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Path Coefficients | Std. Error | t-Value | p Values | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3a | Functional Value -> Consumer Attitude -> Intention to Purchase | 0.144 | 0.039 | 3.724 * | 0.000 | Mediation effect |

| H3b | Symbolic Value -> Consumer Attitude -> Intention to Purchase | 0.048 | 0.028 | 1.726 | 0.084 | No mediation effect |

| H3c | Emotional Value -> Consumer Attitude -> Intention to Purchase | 0.230 | 0.047 | 4.913 * | 0.000 | Mediation effect |

| H3d | Novelty Value -> Consumer Attitude -> Intention to Purchase | −0.040 | 0.027 | 1.474 | 0.141 | No mediation effect |

| H3e | Conditional Value -> Consumer Attitude -> Intention to Purchase | 0.042 | 0.025 | 1.683 | 0.092 | No mediation effect |

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Path Coefficients | Std. Error | t Value | p | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H4 | Moderating Effect (Attitude × Infrastructure Readiness) -> Intention to Purchase | 0.022 | 0.039 | 0.578 | 0.564 | Not Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mohd Noor, N.A.; Muhammad, A.; Isa, F.M.; Shamsudin, M.F.; Abaidah, T.N.A.T. The Electric Vehicle (EV) Revolution: How Consumption Values, Consumer Attitudes, and Infrastructure Readiness Influence the Intention to Purchase Electric Vehicles in Malaysia. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 556. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16100556

Mohd Noor NA, Muhammad A, Isa FM, Shamsudin MF, Abaidah TNAT. The Electric Vehicle (EV) Revolution: How Consumption Values, Consumer Attitudes, and Infrastructure Readiness Influence the Intention to Purchase Electric Vehicles in Malaysia. World Electric Vehicle Journal. 2025; 16(10):556. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16100556

Chicago/Turabian StyleMohd Noor, Nor Azila, Azli Muhammad, Filzah Md Isa, Mohd Farid Shamsudin, and Tunku Nur Atikhah Tunku Abaidah. 2025. "The Electric Vehicle (EV) Revolution: How Consumption Values, Consumer Attitudes, and Infrastructure Readiness Influence the Intention to Purchase Electric Vehicles in Malaysia" World Electric Vehicle Journal 16, no. 10: 556. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16100556

APA StyleMohd Noor, N. A., Muhammad, A., Isa, F. M., Shamsudin, M. F., & Abaidah, T. N. A. T. (2025). The Electric Vehicle (EV) Revolution: How Consumption Values, Consumer Attitudes, and Infrastructure Readiness Influence the Intention to Purchase Electric Vehicles in Malaysia. World Electric Vehicle Journal, 16(10), 556. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16100556